Abstract: On the occasion of the publication in 2014 of the new Handbook of Argumentation Theory, which provides an overview of the current state of the art in the field, van Eemeren identifies three major developments in the treatment of argumentation that he finds promising. First, there is in various theoretical traditions the trend towards empiricalization, which includes both qualitative and quantitative empirical research. Second, there is the increased and explicit attention being paid to the institutional macro-contexts in which argumentative discourse takes place and the effects they have on the argumentation. Third, there is, particularly in the dialectical approaches, a movement towards formalization, which is strongly stimulated by the recent advancement of artificial intelligence. According to van Eemeren, if they are integrated with each other and comply with pertinent academic requirements, the developments of empiricalization, contextualization and formalization of the treatment of argumentation will mean “bingo!” for the future of argumentation theory.

Keywords: contextualization, dialectical perspective, empiricalization, formalization, pragma-dialectics, rhetorical perspective, state of the art

1. Changes in the state of the art of argumentation theory

Since the conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation held in Amsterdam in July 2014 was the eighth ISSA conference, argumentation theorists from various kinds of backgrounds have been exchanging views about argumentation for almost thirty years. My keynote speech at the start of this conference seemed to me the right occasion for making some general comments on the way in which the field is progressing.

I considered myself in a good position to strike a balance because during the past five years I have been preparing an overview of the state of the art in a new Handbook of Argumentation Theory. I have done so together with my co-authors, Bart Garssen, Erik C. W. Krabbe, A. Francisca Snoeck Henkemans, Bart Verheij, and Jean H. M. Wagemans. In this complicated endeavour we have been supported generously by a large group of knowledgeable reviewers and advisors from the field. On the 2 July reception of the ISSA conference the Handbook was to be presented to the community of argumentation scholars.

The Handbook of Argumentation Theory is the latest offshoot of a tradition of handbook writing that I started with Rob Grootendorst in the mid-1970s. We presented first several overviews of the state of the art in Dutch before publishing the handbook in English, the current lingua franca of scholarship (van Eemeren, Grootendorst & Kruiger,1978, 1981, 1986, and van Eemeren, Grootendorst & Kruiger, 1984, 1987, respectively). The most recent version of the handbook is Fundamentals of Argumentation Theory, which appeared in 1996 and was co-authored by a group of prominent argumentation scholars (van Eemeren et al., 1996).

The overview offered by the newly-completed version of the handbook constitutes the basis for giving a judgment of recent developments in the discipline. It goes without saying that a short speech does not allow me to pay attention to all developments that could be of interest; I limit myself to three major trends that I find promising. They involve innovations which are, in my view, vital for the future of the field.

Argumentation scholars are not in full harmony regarding the definition of the term argumentation.[i] There seems to be general agreement however that argumentation always involves trying to convince or persuade others by means of reasoned discourse.[ii] Although I think that most argumentation scholars will agree that the study of argumentation has a descriptive as well as a normative dimension, their views on how in actual research the two dimensions are to be approached will diverge[iii]. Unanimity comes almost certainly to an end when it has to be decided which theoretical perspective is to be favoured.[iv]

The general theoretical perspectives that are dominant are the dialectical, which concentrates foremost on procedural reasonableness, and the rhetorical, focusing on aspired effectiveness. In modern argumentation theory both theoretical traditions are pervaded by insights from philosophy, logic, pragmatics, discourse analysis, communication, and other disciplines. Since the late 1990s, a tendency has developed to connect, or even integrate, the two traditions.[v] Taking only a dialectical perspective involves the risk that relevant contextual and situational factors are not taken into account, while taking a purely rhetorical perspective involves the risk that the critical dimension of argumentation is not explored to the full.[vi]

Compared to some thirty years ago, both the number of participants and the number of publications in argumentation theory have increased strikingly. Another remarkable difference is that nowadays not only North-American and European scholars are involved, but also Latin Americans, Asians and Arabs. In addition, an important impetus to the progress of argumentation theory is given by related disciplines such as critical discourse analysis and persuasion research.[vii]

Today I would like to concentrate on some recent changes in the way in which argumentation is examined. In my opinion, three major developments in the treatment of argumentation have begun to materialize that open up new avenues for research. Although they differ in shape, these developments can be observed across a broad spectrum of theoretical approaches. The three developments I have in mind can be designated as empiricalization, contextualization, and formalization of the treatment of argumentation.[viii]

2. Empiricalization of the treatment of argumentation

Modern argumentation theory manifested itself initially by the articulation of theoretical proposals for concepts and models of argumentation based on new philosophical views of reasonableness. In 1958, Stephen Toulmin presented a model of the various procedural steps involved in putting forward argumentation – or “argument,” as he used to call it (Toulmin, 2003). He emphasized that, in order to deal adequately with the reasonableness of argumentation in the various “fields” of argumentative reality, an empirical approach to argumentation is needed. On their part, Chaïm Perelman and Lucie Olbrechts-Tyteca, who co-founded modern argumentation theory, claimed to have based the theoretical categories of their “new rhetoric” on empirical observations (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969).[ix] Like Frege’s theory of logic was founded upon a descriptive analysis of mathematical reasoning, they founded their argumentation theory on a descriptive analysis of reasoning with value judgments in the fields of law, history, philosophy, and literature.[x]

In spite of their insistence on “empiricalization” of the treatment of argumentation, the empirical dimension of Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s own contributions to argumentation theory remains rather sketchy. In fact, all prominent protagonists of modern argumentation theory in the 1950s, 60s and 70s concentrated in the first place on presenting theoretical proposals for dealing with argumentation and philosophical views in their support. This even applies to the Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss, however practical and empirical his orientation was.[xi] The empirical research Næss wanted to be carried out with regard to argumentation was designed to lead to a more precise determination of the statements about which disagreement exists.[xii] In his own work however he refrained from giving substance to the empirical dimension of argumentation theory.

Despite the strongly expressed preferences of the founding fathers, I conclude that the development of the empirical component of argumentation theory did not really take off until much later. Making such a sweeping statement however, forces you often to acknowledge exceptions immediately. In this case, I must admit that there is an old and rich tradition of empirically-oriented rhetorical scholarship in American communication studies.[xiii] The empirical research that is conducted in this tradition consists for the most part of case studies. One of its main branches, for instance, “rhetorical criticism,” concentrates on analysing specific public speeches or texts that are meant to be persuasive. An excellent specimen is Michael Leff and Gerald Mohrmann’s (1993) analysis of Abraham Lincoln’s Cooper Union speech of February 27, 1860, designed to win nomination as spokesman for the Republican Party. David Zarefsky (1986) offers another example of such empirical research of historical political discourse in President Johnson’s War on Poverty. His more encompassing central question is how Johnson’s social program, put in the strategic perspective of a “war on poverty,” and laid down in the Economic Opportunity Act, gained first such strong support and fell so far later on.

In my view, in argumentation theory argumentative reality is to be examined systematically, concentrating in particular on the influence of certain factors in argumentative reality on the production, interpretation, and assessment of argumentative discourse.[xiv] Two types of empirical research can be pertinent. First, qualitative research relying on introspection and observation by the researcher will usually be most appropriate when specific qualities, traits or conventions of particular specimens of argumentative discourse need to be depicted. Second, as a rule, quantitative research based on numerical data and statistics is required when generic “If X, then Y” claims regarding the production, interpretation or assessment of argumentative discourse must be tested. It is basically the nature of the claim at issue that determines which type of evidence is required – examples or frequencies – and which type of empirical research is therefore most appropriate. Although qualitative as well as quantitative empirical research has its own function in examining argumentative discourse, and the two types of research may complement each other in various ways, carrying out qualitative research is in my opinion always a necessary preparatory step in gaining a better understanding of argumentative reality.[xv]

In France, Marianne Doury has recently carried out qualitative empirical research that is systematically connected with research questions of a more general kind (e.g., Doury, 2006). Her research, which is strongly influenced by insights from discourse and conversation analysis, aims at highlighting “the discursive and interactional devices used by speakers who face conflicting standpoints and need to take a stand in such a way as to hold out against contention” (Doury, 2009, p. 143). Doury focuses on the “spontaneous” argumentative norms revealed by the observation of argumentative exchanges in polemical contexts (Doury, 1997, 2004a, 2005). Her “emic,” i.e. theory-independent, descriptions contribute to a form of argumentative “ethnography” (Doury, 2004b).

In contrast to theoretical research, in “informal logic” empirical research is rather thin on the ground. Nevertheless, Maurice Finocchiaro has carried out important qualitative research projects focusing on reasoning in scientific controversies (e.g., Finocchiaro, 2005b). His approach, which is directed at theorizing, can be characterized as both historical and empirical. Finocchiaro states explicitly that the theory of reasoning he has in mind “has an empirical orientation and is not a purely formal or abstract discipline” (2005a, p. 22).[xvi] Rather than judging arguments in historical controversies from an a priori perspective, as formal logicians do, Finocchiaro holds that the assessment criteria can and should be found empirically within the discourse.

The oldest and most well-known type of quantitative empirical research of argumentation takes place, mainly in the United States, in the related area of persuasion research. More often than not however persuasion research does not concentrate on argumentation. When it does, it deals with the persuasive effects of the way in which argumentation is presented (message structure) and the persuasive effects of the content of argumentation (message content). In the past years, both types of persuasion research have cumulated in large-scale “meta-analyses,” carried out most elaborately by Daniel O’Keefe (2006).

Recently the connection between argumentation and persuasion has been examined more frequently, also outside the United States, in particular by communication scholars from the University of Nijmegen. Their research concentrates for the most part on message content. Hans Hoeken (2001) addressed the relationship between the perception of the quality of an argument and its actual persuasiveness. His initial research, which can be seen as an altered replication of research conducted earlier by Baesler and Burgoon (1994), examined the perceived and actual persuasiveness of three different types of evidence: anecdotal, statistical, and causal evidence. The experimental results indicate that the various types of evidence had a different effect on the acceptance of the claim. However, the differences only partly replicate the pattern of results obtained in other studies. Contrary to expectations, in Hoeken’s study causal evidence proved not to be the most convincing evidence. It was in fact just as persuasive as anecdotal evidence, and less persuasive than statistical evidence.[xvii] Later research conducted in Nijmegen has focused on the relative persuasiveness of different types of arguments.

Since the 1980s, quantitative empirical research has also been carried out in argumentation theory, albeit not by a great many scholars. In order to establish to what extent in argumentative reality the recognition of argumentative moves is facilitated or hampered by factors in their presentation I conducted experimental research together with Grootendorst and Bert Meuffels (van Eemeren, Grootendorst & Meuffels, 1984).[xviii] Dale Hample and Judith Dallinger (1986, 1987, 1991) investigated in the same period the editorial standards people apply in designing their own arguments.[xix] And Judith Sanders, Robert Gass and Richard Wiseman (1991) compared the assessments given by different ethnic groups in evaluating the strength or quality of warrants used in argumentation with assessments given by experts in the field of argumentation and debate (p. 709).[xx]

Several quantitative research projects have concentrated on ordinary arguers’ pre-theoretical quality notions – or norms of reasonableness. Judith Bowker and Robert Trapp (1992), for example, studied laymen’s norms for sound argumentation: Do ordinary arguers apply predictable, consistent criteria on the basis of which they distinguish between sound and unsound argumentation? Their conclusion is that the judgments of the respondents partially correlate with the reasonableness norms formulated by informal logicians such as Ralph Johnson and Anthony Blair, and Trudy Govier (p. 228).[xxi]

Together with Garssen and Meuffels I carried out a comprehensive research project, reported in 2009 in Fallacies and Judgments of Reasonableness, to test experimentally the intersubjective acceptability of the pragma-dialectical norms for judging the reasonableness of argumentative discourse (van Eemeren, Garssen & Meuffels, 2009).[xxii] Rather than being “emic” standards of reasonableness, the pragma-dialectical norms are “etic” standards for resolving differences of opinion on the merits. They are designed to be “problem-valid” – or, in terms of Rupert Crawshay-Williams (1957), methodologically necessary for serving their purpose. Their “intersubjective” – or, in terms of Crawshay-Williams, “conventional” – validity for the arguers however is to be tested empirically. The general conclusion of our extended series of experimental tests is that all data that were obtained indicate that the norms ordinary arguers use when judging the reasonableness of contributions to a discussion correspond quite well with the pragma-dialectical norms for critical discussion. Based on this indirect evidence, the rules may be claimed to be conventionally valid – taken both individually and as a collective.[xxiii]

3. Contextualization of the treatment of argumentation

A second striking development in argumentation theory is the greatly increased attention being paid to the context in which argumentation takes places. By taking explicitly account of contextual differentiation in dealing with the production, analysis and evaluation of argumentative discourse this development goes beyond mere empiricalization. All four levels of context I once proposed to distinguish play a part in this endeavour: the “linguistic,” the “situational,” the “institutional,” and the “intertextual” level (van Eemeren, 2010, pp. 17-19). Most prominent however is the inclusion of the institutional context I designated earlier the macro-context, which pertains to the kind of speech event in which the argumentation occurs. Paying attention to the macro-context is necessary to do justice to the fact that argumentative discourse is always situated in some more or less conventionalized institutional environment, which influences the way in which the argumentation takes shape.

Although in formal and informal logical approaches the macro-context has not very actively been taken into account,[xxiv] in modern argumentation theory the contextual dimension has been emphasized from the beginning. In the rhetorical perspective in particular, contextual considerations have always been an integral part of the approach, starting in Antiquity with the distinction made in Aristotelian rhetoric between different “genres” of discourse. Characteristically, Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca see context in the first place as “audience,” which is accorded a central role in their new rhetoric. Christopher Tindale (1999) insists that in a rhetorical perspective there are still other contextual components than audience that should be taken into account (p. 75).[xxv]

According to Lloyd Bitzer (1999), rhetoric is situational because rhetorical discourse obtains its character from the situation which generates it. By the latter he means that rhetorical texts derive their character from the circumstances of the historic context in which they occur.[xxvi] The rhetorical situation should therefore be regarded “as a natural context of persons, events, objects, relations, and an exigence which strongly invites utterance” (1999, p. 219). Thanks to Bitzer, more and more rhetorical theorists began to realize that their analyses should take the context of the discourse duly into account.

In the 1970s, in “contextualizing” the study of argumentation, American communication scholars picked up Toulmin’s (2003) notion of fields. In 1958, Toulmin had maintained that two arguments are in the same field if their data and claims are of the same logical type. However, the difficulty is that he did not define the notion of “logical type” but only indicated its meaning by means of examples. Some features or characteristics of argument, Toulmin suggested, are field-invariant, while others are field-dependent. In 1972, in Human Understanding, Toulmin had already moved away from this notion of fields, and had come to regard them as akin to academic disciplines.[xxvii]

Because, in Zarefsky’s view, the concept of “fields” offers considerable promise for empirical and critical studies of argumentation, he thought it worthwhile to try to dispel the confusion about the idea of field without abandoning the concept altogether (1992, p. 417).[xxviii] He noted an extensive discussion at conferences of the communication and rhetoric community in the United States on whether “fields” should be defined in terms of academic disciplines or in terms of broad-based world-views such as Marxism and behaviourism (2012, p. 211). It can be observed however that, varying from author to author, the term argument fields is generally used more broadly as a synonym for “rhetorical communities,” “discourse communities,” “conceptual ecologies,” “collective mentalities,” “disciplines,” and “professions.” The common core idea seems to be that claims imply “grounds,” and that the grounds for knowledge claims lie in the epistemic practices and states of consensus in specific knowledge domains.[xxix]

Currently, in communication research in the United States the notion of “argument field” seems to be abandoned. Instead, a contextual notion has become prominent which is similar but not equal to argument field. This is the notion of argument sphere, [xxx] which was in 1982 introduced by Thomas Goodnight.[xxxi] Each argument sphere comes with specific practices.[xxxii] Goodnight offers some examples but does not present a complete list of such practices or an overview of their defining properties. For one thing, spheres of argument differ from each other in the norms for reasonable argument that prevail.[xxxiii] Members of “societies” and “historical cultures” participate, according to Goodnight, in vast, and not altogether coherent, superstructures, which invite them to channel doubts through prevailing discourse practices. In the democratic tradition, these channels can be recognized as the personal, the technical, and the public spheres, which operate through very different forms of invention and subject matter selection.[xxxiv] Inspired by Habermas and the Frankfurt School, Goodnight aims to show that the quality of public deliberation has atrophied since arguments drawn from the private and technical spheres have invaded, and perhaps even appropriated, the public sphere.[xxxv]

A rather new development in the contextualization of the study of argumentation is instigated by Douglas Walton and Erik Krabbe (1995), who take in their dialectical approach the contextual dimension of argumentative discourse into account by differentiating between different kinds of dialogue types: “normative framework[s] in which there is an exchange of arguments between two speech partners reasoning together in turn-taking sequence aimed at a collective goal” (Walton, 1998, p. 30).[xxxvi] Walton and Krabbe’s typology of dialogues consists of six main types: persuasion, negotiation, inquiry, deliberation, information-seeking, and eristics, and additionally some mixed types, such as debate, committee meeting, and Socratic dialogue (1995, p. 66).[xxxvii] The various types of dialogue are characterized by their initial situation, method and goal.[xxxviii]

Over the past decades the pragma-dialectical theorizing too has developed explicitly and systematically towards the inclusion of the contextual dimension of argumentative discourse, especially after Peter Houtlosser and I had introduced the notion of strategic manoeuvring (van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 2002). Strategic manoeuvring does not take part in an idealized critical discussion but in the multi-varied communicative practices that have developed in the various communicative domains. Because these practices have been established in specific communicative activity types, which are characterized by the way in which they are conventionalized, the communicative activity types constitute the institutional macro-contexts in which in “extended” pragma-dialectics argumentative discourse is examined (van Eemeren, 2010, pp. 129-162). The primary aim of this research is to find out in what ways the possibilities for strategic manoeuvring are determined by the institutionally motivated extrinsic constraints, known as institutional preconditions, ensuing from the conventionalization of the communicative activity types concerned.

In order to identify the institutional preconditions for strategic manoeuvring in the communicative activity types they examined, the pragma-dialecticians first determined how these activity types can be characterized argumentatively. Next they tried to establish how the parties involved operate in conducting their argumentative discourse in accordance with the room for strategic manoeuvring available in the communicative activity type concerned. To mention just a few examples: in concentrating on the legal domain, they examined strategic manoeuvring by the judge in a court case (Feteris, 2009); in concentrating on the political domain, strategic manoeuvring by Members of the European Parliament in a general debate (van Eemeren & Garssen, 2011); and in concentrating on the medical domain, the doctor’s strategic manoeuvring in doctor-patient consultation (Labrie, 2012).

Meanwhile, at the University of Lugano, Eddo Rigotti and Andrea Rocci have started a related research program concentrating on argumentation in context. Characteristic of their approach is the combination of semantic and pragmatic insights from linguistics, and concepts from classical rhetoric and dialectic, with insights from argumentation theories such as pragma-dialectics. The communicative activity types they have tackled include mediation meetings from the domain of counseling (Greco Morasso, 2011), negotiations about takeovers from the financial domain (Palmieri, 2014), and editorial conferences from the domain of the media (Rocci & Zampa, 2015).

Recently the pragma-dialectical research of argumentation in context has moved on to the next stage. It is currently aimed at detecting the argumentative patterns of constellations of argumentative moves that, as a consequence of the institutional preconditions for strategic manoeuvring, stereotypically come into being in the various kinds of argumentative practices in the legal, political, medical, and academic domains.[xxxix]

4. Formalization of the treatment of argumentation

The third development I would like to highlight is the “formalization” of the treatment of argumentation. When Toulmin and Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, each in their own way, initiated modern argumentation theory, they agreed – unconsciously but emphatically – that the formal approach to argumentation taken in modern logic was inadequate. In spite of the strong impact of their ideas upon others, their depreciation did not discourage logicians and dialecticians from further developing such a formal approach.

It is important to note that in the various proposals “formality” enters in rather diverse ways and a borderline between approaches that are formal and those that are not is not always easy to draw. A theory of argumentation, whether logical or dialectical, can be “formal” in several senses – and can also be partially formal or formal to some degree.[xl] Generally, in a “formal logical” or a “formal dialectical” argumentation theory “formal” refers to being regimented or regulated. Often, however, “formal” also means that the locutions dealt with in the formal system concerned are rigorously determined by grammatical rules, their logical forms being determined by their linguistic shapes. Additionally, an argumentation theory can be “formal” in the sense that its rules are wholly or partly set up a priori.

A formal theory of argumentation can be put to good use in different ways. The most familiar kind of use probably consists in its application in analyzing and evaluating arguments or an argumentative discussion. Formal systems often used for this purpose are propositional logic and first order predicate logic. Their application consists of “translating” each argument at issue into the language of one of these logics and then determining its validity by a truth table or some other available method.

Using a formal approach to analyse and evaluate real-life argumentative discourse leads to all kinds of problems. Four of them are mentioned in the Handbook. First, the process of translation is not straightforward. Second, a negative outcome does not mean that the argument is invalid – if an argument is not valid according to one system it could still be valid in some other system of logic. Third, by overlooking unexpressed premises and the argument schemes that are used the crux of the argumentation is missed. Fourth, as a consequence, the evaluation is reduced to an evaluation of the validity of the reasoning used in the argumentation, neglecting the appropriateness of premises and the adequacy of the modes of arguing that are employed in the given context. Formal logic can be of help in reconstructing and assessing argumentation, but an adequate argumentation theory needs to be more encompassing and more communication-oriented.

A second way of using formal systems consists in utilizing or constructing them to contribute to the theoretical development of argumentation theory by providing clarifications of certain theoretical concepts. In this way, John Woods and Douglas Walton (1989), for instance, show how formal techniques can be helpful in dealing with the fallacies. Employing formal systems to instigate theoretical developments is, in my view, more rewarding that just using them in analyzing and evaluating argumentative discourse.

From Aristotle’s Prior Analytics onwards, logicians have been chiefly concerned with the formal validity of deductions, pushing the actual activity of arguing in discussions into the background. This has divorced logic as a discipline from the practice of argumentation. Paul Lorenzen (1960) and his Erlangen School have made it possible to counteract this development. They promoted the idea that logic, instead of being concerned with a rational mind’s inferences or truth in all possible worlds, should focus on discussion between two disagreeing parties in the actual world. They thus helped to bridge the gap between formal logic and argumentation theory noted by Toulmin and the authors of The New Rhetoric.

Because Lorenzen did not present his insights as a contribution to argumentation theory, their important implications for this discipline were initially not evident. In fact, Lorenzen took not only the first step towards a re-dialectification of logic, but his insights concerning the dialogical definition of logical constants also signal the initiation of a pragmatic approach to logic. In From Axiom to Dialogue, Else Barth and Erik Krabbe (1982) incorporated his insights in a formal dialectical theory of argumentation. Their primary purpose was “to develop acceptable rules for verbal resolution of conflicts of opinion” (p. 19). The rules of the dialectical systems they propose, which are “formal” in the regulative and sometimes also in the linguistic sense, standardize reasonable and critical discussions.

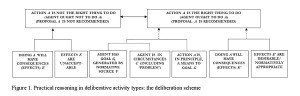

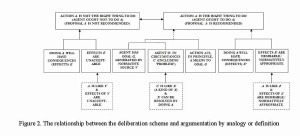

A third kind of use of formal systems consists in using them as a source of inspiration for developing a certain approach to argumentation. Such an approach may itself be informal or only partly formal. In argumentation theory the approaches inspired by formal studies serve as a link between formal and informal approaches. The semi-formal method of “profiles of dialogue” is a case in point.[xli] A profile of dialogue is typically written as an upside down tree diagram, consisting of nodes linked by line segments. Each branch of the tree displays a possible dialogue that may develop from the initial move. The nodes are associated with moves and the links between the nodes correspond to situations in the dialogue.

In pragma-dialectics, the method of profiles of dialogue inspired in its turn the use of “dialectical profiles” (van Eemeren, Houtlosser & Snoeck Henkemans, 2007, esp. Section 2.3), which are equally semi-formal as argument schemes and argumentation structures. A dialectical profile is “a sequential pattern of the moves the participants in a critical discussion are entitled to make – and in one way or another have to make – to realize a particular dialectical aim at a particular stage or sub-stage of the resolution process” (van Eemeren, 2010, p. 98).

A fourth and last use of a formal approach proceeds into the opposite direction. This is, for instance, the case when insights from argumentation theory are employed for creating formal applications in Artificial Intelligence. In return, of course, Artificial Intelligence offers argumentation theory a laboratory for examining implementations of its rules and concepts. Formal applications of insights from argumentation theory in Artificial Intelligence vary from making such insights instrumental in the construction of “argumentation machines,” or at any rate visualization systems, interactive dialogue systems, and analysis systems, to developing less comprehensive tools for automated analysis. Of preeminent importance in these endeavours is the philosophical notion of defeasible reasoning, referring to inferences that can be blocked or defeated (Nute, 1994, p. 354). In 1987, John Pollock pointed out that “defeasible reasoning” is captured by what in Artificial Intelligence is called a non-monotonic logic. A logic is non-monotonic when a conclusion that, according to that logic, follows from certain premises need not always follow when more premises are added. In a non-monotonic logic, it is possible to draw tentative conclusions while keeping open the possibility that additional information may lead to their retraction.[xlii]

Although in The Uses of Argument the term defeasible is rarely used, Toulmin (2003) is obviously an early adopter of the idea of defeasible reasoning. He acknowledges that his key distinctions of “claims,” “data,” “warrants,” “modal qualifiers,” “conditions of rebuttal,” and his ideas about the applicability or inapplicability of warrants, “will not be particularly novel to those who have studied explicitly the logic of special types of practical argument” (p. 131). Toulmin notes that H. L. A. Hart has shown the relevance of the notion of defeasibility for jurisprudence, free will, and responsibility and that David Ross has applied it to ethics, recognizing that moral rules may hold prima facie, but can have exceptions. The idea of a prima facie reason is closely related to non-monotonic inference: Q can be concluded from P but not when there is additional information R.

In order to take the possibility of defeating circumstances into account, in Artificial Intelligence the notion from argumentation theory called argument scheme or argumentation scheme has been taken up.[xliii] The critical questions associated with argument schemes correspond to defeating circumstances. Floris Bex, Henry Prakken, Christopher Reed and Walton (2003) have applied the concept of argumentation scheme, for instance, to the formalization of legal reasoning from evidence. One of the argument schemes they deal with is argument from expert opinion.

Viewed from the perspective of Artificial Intelligence, the work on argument schemes of Walton and his colleagues can be regarded as a contribution to the theory of knowledge representation. This knowledge representation point of view is further developed by Bart Verheij (2003b). Like Bex, Prakken, Reed and Walton (2003), he formalizes argument schemes as defeasible rules of inference.[xliv]

5. Bingo!

In my view, argumentation theory can only be a relevant discipline if it provides insights that enable a better understanding of argumentative reality. The empiricalization, contextualization, and formalization of the treatment of argumentation I have sketched are necessary preconditions for achieving this purpose. Without empiricalization, the connection with argumentative reality is not ensured. Without contextualization, there is no systematic differentiation of the various kinds of argumentative practices. Without formalization, the required precision and rigour of the theorizing are lacking.

Only if all three developments have come to full fruition, an understanding of argumentative reality can be achieved that constitutes a sound basis for practical intervention by proposing alternative formats and designs for argumentative practices, whether computerized or not, and developing methods for improving productive, analytic, and evaluative argumentative skills. In each case, however, there are certain prerequisites to the indispensable empiricalization, contextualization, and formalization of the treatment of argumentation.

Case studies, for instance, can play a constructive role in gaining insight into argumentative reality by means of empirical research, but, however illuminating they may be, they are not instrumental in the advancement of argumentation theory if they only enhance our understanding of a particular case. Mutatis mutandis, the same applies to other qualitative and quantitative empirical research that lacks theoretical relevance.[xlv] Some scholars think wrongly that qualitative research is superior because it “goes deeper” and leads to “real” insight, while other scholars, just as wrongly, consider quantitative research superior because it is “objective” and leads to “generalizable” results.[xlvi] In my view, both types of research are necessary for a complete picture of argumentative reality, sometimes even in combination.[xlvii] In all cases however it is a prerequisite that the research is systematically related to well-defined theoretical issues and relevant to the advancement of argumentation theory.

In gaining insight into the contextual constraints on argumentative discourse both analytical considerations concerning the rationale of a specific argumentative practice and a practical understanding of how this rationale is implemented in argumentative discourse play a part. In order to contribute to the advancement of argumentation theory as a discipline, the analytical considerations concerning the rationale of an argumentative practice should apply to all specimens of that particular communicative activity type – or dialogue type, if a different theoretical approach is favoured. To enable methodical comparisons between different types of communicative activities, and avoid arbitrary proliferation, the description of the implementation of the rationale must take place in functional and well-defined theoretical categories.

In the recent trend towards formalization, which has been strongly stimulated by the connection with computerization in the interdisciplinary field of artificial intelligence, not only logic-related approaches to argumentation are utilized, but also the Toulmin model and a variety of other theories of argumentation structure and argument schemes, such as Walton and Krabbe’s (1995). However, responding to the need for formal adequacy so strongly felt in information science may go at the expense of material adequacy, that is, at the expense of the extent to which the formalized theorizing covers argumentative reality. Relying at any cost on the formal and formalizable theoretical designs that are available in argumentation theory, however weak their theoretical basis may sometimes be, can easily lead to premature or too drastic formalizations and half-baked results. Because of the eclecticism involved in randomly combining incompatible insights from different theoretical approaches, these results may even be incoherent.

Provided that the prerequisites just mentioned are given their due, empiricalizing, contextualizing, and formalizing the treatment of argumentation are crucial to the future of argumentation theory, and more particularly to its applications and computerization. As the title of my keynote speech indicates, succeeding in properly combining and integrating the three developments would, in my view, mean: “Bingo!”.

Let me conclude by illustrating my point with the help of a research project I am presently involved in with a team of pragma-dialecticians. The project is devoted to what I have named argumentative patterns (van Eemeren, 2012, p. 442). Argumentative patterns are structural regularities in argumentative discourse that can be observed empirically. These patterns can be characterized with the help of the theoretical tools provided by argumentation theory. Their occurrence can be explained by the institutional preconditions for strategic manoeuvring pertaining to a specific communicative activity type.

Dependent on the exigencies of a communicative domain, in the various communicative activity types different kinds of argumentative exchanges take place. The discrepancies are caused by the kind of difference of opinion to which in a particular communicative activity type the exchanges respond, the type of standpoint at issue, the procedural and material starting points, the specific requirements regarding the way in which the argumentative exchange is supposed to take place, and the kind of outcome allowed.[xlviii]

Each argumentative pattern that can be distinguished in argumentative reality is characterized by a constellation of argumentative moves in which, in dealing with a particular kind of difference of opinion, in defence of a particular type of standpoint, a particular argument scheme or combination of argument schemes is used in a particular kind of argumentation structure (van Eemeren, 2012).[xlix] The theoretical instruments used by the pragma-dialecticians in their qualitative empirical research aimed at identifying argumentative patterns occurring in argumentative reality, such as the typologies of standpoints, differences of opinions, argument schemes, and argumentation structures,[l] are formalized to a certain degree.[li] Further formalization is required, in particular for computerization, which is nowadays a requirement for the various kinds of applications in actual argumentative practices instrumental in realizing the practical ambitions of argumentation theory.[lii]

Certain argumentative patterns are characteristic of the way in which argumentative discourse is generally conducted in specific communicative activity types. In parliamentary policy debates, for example, a “stereotypical” argumentative pattern that can be found consists of a prescriptive standpoint that a certain policy should be carried out, justified by pragmatic argumentation, supported by arguments from example. Such stereotypical argumentative patterns are of particular interest to pragma-dialecticians because an identification of the argumentative patterns typically occurring in particular communicative activity types is more insightful than, for instance, just listing the types of standpoints at issue or the argument schemes that are frequently used.[liii] Thus documenting the institutional diversification of argumentative practices paves the way for a systematic comparison and a theoretical account of context-independency and context-dependency in argumentative discourse that is more thorough, more refined, and better supported than Toulmin’s account and other available accounts. In this way, our current research systematically tackles one of the fundamental problems of argumentation theory: universality versus particularity.

NOTES

i. See van Eemeren (2010, pp. 25-27) for the influence of being or not being a native speaker of English on the perception of argumentation and argumentation theory.

ii. In my view, instead of being a theory of proof or a general theory of reasoning or argument, argumentation theory concentrates on using argument to convince others by a reasonable discussion of the acceptability of the standpoints at issue. My view of argumentation theory is generally incorporated in more-encompassing views that have been advanced.

iii. As we observed in the new Handbook, “[s]ome argumentation theorists have a goal that is primarily (and sometimes even exclusively) descriptive, especially those theorists having a background in linguistics, discourse analysis, and rhetoric. They are interested, for instance, in finding out how in argumentative discourse speakers and writers try to convince or persuade others by making use of certain linguistic devices or by using other means to influence their audience or readership. Other argumentation theorists, often inspired by logic, philosophy, or insights from law, study argumentation primarily for normative purposes. They are interested in developing soundness criteria that argumentation must satisfy in order to qualify as rational or reasonable. They examine, for instance, the epistemic function argumentation fulfills or the fallacies that may occur in argumentative discourse” (van Eemeren et al., 2014, p. 29).

iv. According to the Handbook of argumentation theory, “The current state of the art in argumentation theory is characterized by the co-existence of a variety of theoretical perspectives and approaches, which differ considerably from each other in conceptualization, scope, and theoretical refinement” (van Eemeren et al., 2014, p. 29).

v. See for various views on combining insights from dialectic and rhetoric van Eemeren and Houtlosser (Eds., 2002). Van Eemeren and Houtlosser (2002) have proposed to integrate insights from rhetoric into the theoretical framework of pragma-dialectics. According to Tindale, who considers the rhetorical perspective as the most fundamental, the synthesis of the logical, dialectical and rhetorical perspectives should be grounded in the rhetorical perspective (1999, pp. 6-7).

vi. In our new Handbook we take the position that argumentation theory can best be viewed as an interdisciplinary study with logical, dialectical, and rhetorical dimensions (van Eemeren et al., 2014, p. 29).

vii. According to van Eemeren et al. (2014), a great number of contributions to the study of argumentation are not part of the generally recognized research traditions; some of them stem from related disciplines or have been developed in non-Anglophone parts of the world. See Chapter 12 of the Handbook.

viii. It goes without saying that, depending on one’s theoretical position and preferences, other promising trends can be distinguished. A case in point may be the study of visual and other modalities of argumentation.

ix. In spite of various criticisms of the empirical adequacy of Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca’s taxonomy of argument schemes (van Eemeren et al., 1996, pp. 122-124; van Eemeren et al., 2014, p. 292), Warnick and Kline (1992) have made an effort to carry out empirical research based on this taxonomy.

x. The norms for rationality and reasonableness described in the new rhetoric have an “emic” basis: the criteria for the evaluation of argumentation that Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca provide are a description of various kinds of argumentation that can be successful in practice with the people for whom the argumentation is intended.

xi. In Interpretation and Preciseness, published in 1953, Næss revealed himself as a radical empirical semanticist, who liked questionnaires and personal interviews to be used for investigating what in particular circles is understood by particular expressions. However, he did not carried out such investigations himself.

xii. Although Næss’s empirical ideas stimulated the coming into existence of the “Oslo School,” a group of researchers investigating semantic relations, such as synonymy, by means of questionnaires, their influence in argumentation theory has been rather limited.

xiii. Already since the 1950s, contemporary argumentative discourse in the political domain has been carefully studied by rhetoricians such as Robert Newman (1961) and Edward Schiappa (2002), to name just two outstanding examples from different periods.

xiv. Because of its ambition to be an academic discipline which is of practical relevance in dealing with argumentative reality, argumentation theory needs to include empirical research relating to the philosophically motivated theoretical models that have been developed. To see to what extent argumentative reality agrees with the theory, the research programme of an argumentation theory such as pragma-dialectics therefore has an empirical component.

xv. Although in general quantitative research is only necessary with regard to more general claims, claims pertaining to a specific case can sometimes also be supported quantitatively. In any case, quantitative research is only relevant to argumentation theory if it increases our insight into argumentative reality.

xvi. At the same time, Finocchiaro emphasizes that “the empirical is contrasted primarily to the a priori, and not, for example, to the normative or the theoretical” (2005a, p. 47).

xvii. Corresponding with its actual persuasiveness, statistical evidence is rated as stronger than anecdotal evidence. Ratings of the strength of the argument are in both cases strongly related to its actual persuasiveness. In contrast, causal evidence received higher ratings compared to its actual persuasiveness.

xviii. See Garssen (2002) for experimental research into whether ordinary arguers have a pre-theoretical notion of argument schemes.

xix. More recently, Hample collaborated with Fabio Paglieri and Ling Na (2011) in answering the question of when people are inclined to start a discussion.

xx. Another type of quantitative research focuses on cognitive processes. Voss, Fincher-Kiefer, Wiley and Ney Silfies (1993), for instance, present a model of informal argument processing and describe experiments that provide support for the model.

xxi. Making also use of an “empiricistic” method, Schreier, Groeben and Christmann (1995) introduced the concept of argumentational integrity to develop ethical criteria for assessing contributions to argumentative discussions in daily life based on experimental findings.

xxii. This research was, of course, not aimed at legitimizing the model of a critical discussion. All the same, by indicating which factors are worth investigating because of their significance for resolving a difference of opinion on the merits, the model gives direction to the research.

xxiii. Within the field of experimental psychology, Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber (2011) have recently proposed an “argumentative theory” which hypothesizes that the (main) function of reasoning is argumentative: “to produce arguments so we can convince others and to evaluate others’ arguments so as to be convinced only when appropriate” (Mercier, 2012, pp. 259-260). Putting forward this hypothesis on the function of reasoning enables them to (re)interpret many of the findings of tests conducted in experimental psychology. As to further research, Mercier (2012, p. 266) proposes to take typologies regarding argument schemes and their associated critical questions developed in argumentation theory as a starting point for experimental studies regarding the evaluation of arguments. In this way, it might become clear which cognitive mechanisms are at play when people evaluate certain types of argumentation.

xxiv. The exception is “natural logic,” which studies arguments in a context of situated argumentative discourse in describing the “logic” of ordinary argumentative discourse in a non-normative, “naturalistic” way.

xxv. A first contextual component Tindale (1999) distinguishes is locality, “the time and the place in which the argument is located” (p. 75); a second one is background, “those events that bear on the argumentation in question” (p. 76); a third one is the arguer, the source of the argumentation (p. 77); and a fourth component of context he distinguishes is expression, the way in which the argument is expressed (p. 80). Characteristically, Tindale defines audience relevance – an important element of contextual relevance which is a precondition for the acceptability of argumentation – as “the relation of the information-content of an

argument, stated and assumed, to the framework of beliefs and commitments that are likely to be held by the audience for which it is intended” (1999, p. 102, my italics).

xxvi. In Bitzer’s view, every rhetorical situation has three constituents: (1) the exigence that is the “imperfection” (problem, defect or obstacle) which should be changed by the discourse; (2) the audience that is required because rhetorical discourse produces change by influencing the decisions and actions of persons who function as a “mediator of change”; and (3) the constraints of the rhetorical situation which influence the rhetor and can be brought to bear upon the audience (pp. 220-221). The rhetorical situation may therefore be defined as “a complex of persons, events, objects, and relations presenting an actual or potential exigence which can be completely or partially removed if discourse, introduced into the situation, can so constrain human decision or action as to bring about the significant modification of the exigence” (Bitzer, 1999, p. 220).

xxvii. In spite of the confusion, some argumentation scholars still found the idea of argument fields useful for distinguishing between field-invariant aspects of argument and aspects of argument that vary from field to field.

xxviii. Zarefsky identifies and discusses three recurrent issues in theories about argument fields: the purpose of the concept of argument fields, the nature of argument fields, and the development of argument fields.

xxix. The positions of the advocates of the various denominators can be interpreted by inferring the kinds of backgrounds they presuppose: the traditions, practices, ideas, texts, and methods of particular groups (Dunbar, 1986; Sillars, 1981). Willard, for one, advocated a sociological-rhetorical version of the field theory. For him, fields are “sociological entities whose unity stems from practices” (1982, p. 75). Consistent with the Chicago School, Willard defines fields as existing in the actions of the members of a field. These actions are in his view essentially rhetorical. Rowland (1992, p. 470) also addresses the meaning and the utility of argument fields. He argues for a purpose-centred approach. In his view, the essential characteristics of an argument field are best described by identifying the purpose shared by members of the field (p. 497).

xxx. See Goodnight (1980, 1982, 1987a, 1987b). For a collection of papers devoted to spheres of argument, see Gronbeck (Ed., 1989).

xxxi. Although Goodnight does not reject the notion of argument field, he finds it “not a satisfactory umbrella for covering the grounding of all arguments” (2012, p. 209). In his view, the idea that all arguments are “grounded in fields, enterprises characterized by some degree of specialization and compactness, contravenes an essential distinction among groundings” (p. 209).

xxxii. Zarefsky (2012, pp. 212-213) proposes a taxonomical scheme for spheres which consists of the following distinguishing criteria: Who participates in the discourse? Who sets the rules of procedure? What kind of knowledge is required? How are the contributions to be evaluated? What is the end-result of the deliberation?

xxxiii. While the notion of “argument field” seems to be abandoned, argumentation scholars still frequently use the notion of “sphere.” Schiappa (2012), for instance, compares and contrasts in his research the arguments advanced in the technical sphere of legal and constitutional debate with those used in the public sphere.

xxxiv. Michael Hazen and Thomas Hynes (2011) focus on the functioning of argument in the public and private spheres of communication (or, as they call them, “domains”) in different forms of society. While an extensive literature exists on the role of argument in democracy and the public sphere, there is no corresponding literature regarding non-democratic societies.

xxxv. Goodnight (2012) suggests that the grounds of argument may be altered over time: A way of arguing appropriate to a given sphere can be shifted to a new grounding. This means that spheres start to intermingle. It is important to realize that Goodnight combines in fact two ideas (the idea of the spheres and the idea of a threat to the public sphere), but that this is not necessary: One can find the “spheres” notion analytically useful without accepting the idea of a threat to the public sphere.

xxxvi. Walton (1998) defines a dialogue as a “normative framework in which there is an exchange of arguments between two speech partners reasoning together in turn-taking sequence aimed at a collective goal” (p. 30). There is a main goal, which is the goal of the dialogue, and there are goals of the participants. The two kinds of goals may or may not correspond.

xxxvii. In a recent version of the typology (Walton, 2010), the list consists of seven types, since a dialogue type called discovery, attributed to McBurney and Parsons (2001), is added to the six types just mentioned.

xxxviii. An inquiry, for instance, has a lack of proof as its initial situation, uses knowledge-based argumentation as a method, and has the establishment of proof as a goal.

xxxix. The underlying assumption here is that in the argumentation stage protagonists may in principle be supposed to aim for making the strongest case in the macro-context concerned by trying to advance a combination of reasons that will satisfy the antagonist by leaving no critical doubts unanswered. In the process they may be expected to exploit the argument schemes they consider most effective in the situation at hand and to use all multiple, coordinative and subordinative argumentation that is necessary to respond to the critical reactions the antagonist may be expected to come up with.

xl. Of the three distinct senses of “formal” pointed out by Barth and Krabbe (1982, pp. 14-19), and the two added by Krabbe (1982, p. 3), only three are pertinent to argumentation theory. Krabbe’s first sense refers to Platonic forms and need not be considered here. The same goes for the fifth sense, which refers to systems that are purely logical, i.e., that do not provide for any material rule or move.

xli. Walton was probably the first to introduce profiles of dialogues by that name (1989a, pp. 37-38; 1989b, pp. 68-69). Other relevant publications are Krabbe (2002) and van Laar (2003a, 2003b).

xlii. Dung (1995) initiated the study of argument attack as a (mathematical) directed graph, and showed formal connections between non-monotonic logic and argumentation. Just like Bondarenko et al. (1997), Verheij (2003a) developed an assumption-based model of defeasible argumentation. Prakken (1997) explored the connection between non-monotonic logic and legal argumentation.

xliii. In the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation, argument schemes are distinguished from the formal schemes of reasoning of logic. These argument schemes are defeasible. They play a vital role in the intersubjective testing procedure, which boils down to asking critical questions and reacting to them. By asking critical questions, the antagonist challenges the protagonist to make clear that, in the particular case at hand, there are no exceptions to the general rule invoked by the use of the argument scheme concerned.

xliv. Reed and Rowe (2004) have incorporated argument schemes in their Araucaria tool for the analysis of argumentative texts. Rahwan, Zablith and Reed (2007) have proposed formats for the integration of argument schemes in what is called the Semantic Web. Gordon, Prakken and Walton (2007) have integrated argument schemes in their Carneades model.

xlv. A great deal of the qualitative empirical research that has been carried out in argumentation theory is not only case-based but also very much ad hoc. In addition, a great deal of the quantitative persuasion research that is carried out suffers from a lack of theoretical relevance.

xlvi. An additional problem is that the distinction between qualitative and quantitative research is not always defined in the same way. Psychologists and sociologists, for instance, tend to consider interviews and introspection as qualitative research because the results are not reported in numerical terms and statistics does not play a role. There are also less restrictive views, in which numerical reporting and the use of statistics are not the only distinctive feature.

xlvii. In the pragma-dialectical empirical research concerning fallacies, for instance, qualitative and quantitative research are methodically combined – in this case by having a qualitative follow-up of the quantitative research, as reported in van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels (2009).

xlviii. Viewed dialectically, argumentative patterns are generated by the protagonist’s responding to, or anticipating, (possible) criticisms of the would-be antagonist, such as critical questions associated with the argument schemes that are used.

xlix. If an argument in defence of a standpoint is expected not to be accepted immediately, then more, other, additional or supporting arguments (or a combination of those) need to be advanced, which leads to an argumentative pattern with a complex argumentation structure (cumulative coordinative, multiple, complementary coordinative or subordinative argumentation (or a combination of those), respectively).

l. We will make use of the qualitative method of analytic induction (see, for instance, Jackson, 1986).

li. To determine and compare the frequencies of occurrence of the various stereotypical argumentative patterns that have been identified on analytical grounds while qualitative research has made clear how they occur, the qualitative empirical research will be followed by quantitative empirical research of representative corpuses of argumentative discourse to establish the frequency of occurrence of these patterns. This quantitative research needs to be based on the results of analytic and qualitative research in which it is established which argumentative patterns are functional in specific (clusters of) communicative activity types, so that theoretically motivated expectations (hypotheses) can be formulated about the circumstances in which specific argumentative patterns occur in particular communicative activity types and when they will occur.

lii. In view of the possibilities of computerization, other theories of argumentation that have been formalized only to a certain degree could in principle benefit equally from further formalization.

liii. An argumentative pattern become stereotypical due to the way in which the institutional preconditions pertaining to a certain communicative activity type constrain the kinds of standpoints, the kinds of criticisms and the types of arguments that may be advanced.

References

Baesler, J. E., & Burgoon, J. K. (1994). The temporal effects of story and statistical evidence on belief change. Communication Research, 21, 582–602.

Barth, E. M., & Krabbe, E. C. W. (1982). From axiom to dialogue. A philosophical study of logics and argumentation. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Bex, F. J., Prakken, H., Reed, C., & Walton, D. N. (2003). Towards a formal account of reasoning about evidence. Argumentation schemes and generalisations. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 11, 125–165.

Bitzer, L. F. (1999). The rhetorical situation. In J. L. Lucaites, C. M. Condit & S. Caudill (Eds.), Contemporary rhetorical theory. A reader. New York: Guilford Press.

Bondarenko, A., Dung, P. M., Kowalski, R. A., & Toni, F. (1997). An abstract, argumentation-theoretic approach to default reasoning. Artificial Intelligence, 93, 63-101.

Bowker, J. K., & Trapp, R. (1992). Personal and ideational dimensions of good and poor arguments in human interaction. In F. H. van Eemeren & R. Grootendorst (Eds.), Argumentation illuminated (pp. 220-230). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Crawshay-Williams, R. (1957). Methods and criteria of reasoning. An inquiry into the structure of controversy. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Doury, M. (1997). Le débat immobile. L’argumentation dans le débat médiatique sur les parasciences [The immobile debate. Argumentation in the media debate on the parasciences]. Paris: Kimé.

Doury, M. (2004a). La classification des arguments dans les discours ordinaires [The classification of arguments in ordinary discourse]. Langage, 154, 59-73.

Doury, M. (2004b). La position de l’analyste de l’argumentation [The position of the argumentation analyst]. Semen, 17, 143-163.

Doury, M. (2005). The accusation of amalgame as a meta-argumentative refutation. In F. H. van Eemeren & P. Houtlosser P. (Eds.), The practice of argumentation (pp. 145-161). Amsterdam-Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Doury, M. (2006). Evaluating analogy. Toward a descriptive approach to argumentative norms. In P. Houtlosser & M. A. van Rees (Eds.), Considering pragma-dialectics. A festschrift for Frans H. van Eemeren on the occasion of his 60th birthday (pp. 35-49). Mahwah, NJ-London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Doury, M. (2009). Argument schemes typologies in practice. The case of comparative arguments. In: F. H. van Eemeren & B. Garssen (Eds.), Pondering on problems of argumentation (pp. 141-155). New York: Springer.

Dunbar, N. R. (1986). Laetrile. A case study of a public controversy. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 22, 196–211.

Dung, P. M. (1995). On the acceptability of arguments and its fundamental role in non-monotonic reasoning, logic programming and n-person games. Artificial Intelligence, 77, 321-357.

Eemeren, F. H. van (2010). Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse. Extending the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. Amsterdam-Philadelphia: John Benjamins. (transl. into Chinese (in preparation), Italian (2014), Japanese (in preparation), Spanish (2013b)).

Eemeren, F. H. van (2012). The pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation under discussion. Argumentation, 26(4), 439-457.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Garssen, B. (2011). Exploiting the room for strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse. Dealing with audience demand in the European Parliament. In F. H. van Eemeren & B. Garssen (Eds.), Exploring argumentative contexts. Amsterdam-Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Eemeren, F. H. van, Garssen, B., Krabbe, E. C. W., Snoeck Henkemans, A. F., Verheij, B., & Wagemans, J. H. M. (2014). Handbook of argumentation theory. Dordrecht etc.: Springer Reference.

Eemeren, F. H. van, Garssen, B., & Meuffels, B. (2009). Fallacies and judgments of reasonableness. Empirical research concerning the pragma-dialectical discussion rules. Dordrecht etc.: Springer.

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst, R., & Kruiger, T. (1978). Argumentatietheorie [Argumentation theory]. Utrecht: Het Spectrum. (2nd enlarged ed. 1981; 3rd ed. 1986). (English transl. (1984, 1987).

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst, R., & Kruiger, T. (1981). Argumentatietheorie [Argumentation theory]. 2nd enlarged ed. Utrecht: Het Spectrum. (1st ed. 1978; 3rd ed. 1986). (English transl. (1984, 1987)).

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst, R., & Kruiger, T. (1984). The study of argumentation. New York: Irvington. (Engl. transl. by H. Lake of F. H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst & T. Kruiger (1981). Argumentatietheorie. 2nd ed. Utrecht: Het Spectrum). (1 st ed. 1978).

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst, R., & Kruiger, T. (1986). Argumentatietheorie [Argumentation theory]. 3rd ed. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff. (1st ed. 1978, Het Spectrum).

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst, R., & Kruiger, T. (1987). Handbook of argumentation theory. A critical survey of classical backgrounds and modern studies. Dordrecht-Providence: Foris. (English transl. by H. Lake of F. H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst & T. Kruiger (1981). Argumentatietheorie. Utrecht etc.: Het Spectrum).

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst, R., & Meuffels, B. (1984). Het identificeren van enkelvoudige argumentatie [Identifying single argumentation]. Tijdschrift voor Taalbeheersing, 6(4), 297-310.

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst, R., & Snoeck Henkemans, A. F., with Blair, J. A., Johnson, R. H., Krabbe, E. C. W., Plantin, C., Walton, D. N., Willard, C. A., Woods, J., & Zarefsky, D. (1996). Fundamentals of argumentation theory. Handbook of historical backgrounds and contemporary developments. Mawhah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. (transl. into Dutch (1997)).

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2002). Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse. Maintaining a delicate balance. In F. H. van Eemeren & P. Houtlosser (Eds.), Dialectic and rhetoric. The warp and woof of argumentation analysis (pp. 131-159). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Eemeren, F. H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (Eds., 2002). Dialectic and rhetoric. The warp and woof of argumentation analysis. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Eemeren, F. H. van, Houtlosser, P., & Snoeck Henkemans, A. F. (2007). Argumentative indicators in discourse. A pragma-dialectical study. Dordrecht: Springer.

Feteris, E. T. (2009). Strategic maneuvering in the justification of judicial decisions. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Examining argumentation in context. Fifteen studies on strategic maneuvering (pp. 93-114). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Finocchiaro, M. A. (2005a). Arguments about arguments. Systematic, critical and historical essays in logical theory. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Finocchiaro, M. A. (2005b). Retrying Galileo, 1633–1992. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Garssen, B. J. (2002). Understanding argument schemes. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Advances in pragma-dialectics (pp. 93-104). Amsterdam-Newport News, VA: Sic Sat &Vale Press.

Goodnight, G. Th. (1980). The liberal and the conservative presumptions. On political philosophy and the foundation of public argument. In J. Rhodes & S. Newell (Eds.), Proceedings of the [first] summer conference on argumentation (pp. 304–337). Annandale, VA: Speech Communication Association.

Goodnight, G. T. (1982). The personal, technical, and public spheres of argument. A speculative inquiry into the art of public deliberation. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 18, 214–227.

Goodnight, G. T. (1987a). Argumentation, criticism and rhetoric. A comparison of modern and post-modern stances in humanistic inquiry. In J. W. Wenzel (Ed.), Argument and critical practices. Proceedings of the fifth SCA/AFA conference on argumentation (pp. 61–67). Annandale, VA: Speech Communication Association.

Goodnight, G. T. (1987b). Generational argument. In F. H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J. A. Blair & C. A. Willard (Eds.), Argumentation. Across the lines of discipline. Proceedings of the conference on argumentation 1986 (pp. 129–144). Dordrecht-Providence: Foris.

Goodnight, G. T. (2012). The personal, technical, and public spheres. A note on 21st century critical communication inquiry. Argumentation and Advocacy, 48(4), 258-267.

Gordon, T. F., Prakken, H., & Walton, D. N. (2007). The Carneades model of argument and burden of proof. Artificial Intelligence, 171, 875–896.

Greco Morasso, S. (2011). Argumentation in dispute mediation. A reasonable way to handle conflict. Amsterdam-Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Gronbeck, B. E. (Ed., 1989). Spheres of argument. Proceedings of the sixth SCA/AFA conference on argumentation. Annandale, VA: SCA.

Hample, D., & Dallinger, J. (1986). The judgment phase of invention. In F. H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J. A. Blair & C. A. Willard (Eds.), Argumentation. Across the lines of discipline. Proceedings of the conference on argumentation 1986 (pp. 225-234). Dordrecht-Providence: Foris.

Hample, D., & Dallinger, J. M. (1987). Cognitive editing of argument strategies. Human Communication Research, 14, 123-144.

Hample, D., & Dallinger J. M. (1991) Cognitive editing of arguments and interpersonal construct differentiation. Refining the relationship. In F. H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J. A. Blair & C. A. Willard (Eds.). Proceedings of the second international conference on argumentation (organized by the International Society for the Study of Argumentation at the University of Amsterdam, June 19–22, 1990) (pp. 567-574). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Hample, D., Paglieri, F., & Na, L. (2011). The costs and benefits of arguing. Predicting the decision whether to engage or not. In F. H. van Eemeren, B. J. Garssen, D. Godden & G. Mitchell (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7thconference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 718-732). Amsterdam: Rozenberg/Sic Sat. [CD ROM].

Hazen, M. D., & Hynes, T. J. (2011). An exploratory study of argument in the public and private domains of differing forms of societies. In F. H. van Eemeren, B. Garssen, D. Godden & G. Mitchell (Eds.) Proceedings of the 7th conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 750-762). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Jackson, S. (1986). Building a case for claims about discourse structure. In D. G. Ellis & W. A. Donohane (Eds.). Contemporary issues in language and discourse. (pp. 129-147). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Krabbe, E. C. W. (1982). Studies in dialogical logic. Doctoral dissertation University of Groningen.

Krabbe, E. C. W. (2002). Profiles of dialogue as a dialectical tool. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Advances in pragma-dialectics (pp. 153-167). Amsterdam: Sic Sat & Newport News, VA: Vale Press.

Laar, J. A. van (2003a). The dialectic of ambiguity. A contribution to the study of argumentation. Doctoral dissertation University of Groningen.

Laar, J. A. van (2003b). The use of dialogue profiles for the study of ambiguity. In F. H. van Eemeren, J. A Blair, C. A. Willard & A. F. Snoeck Henkemans (Eds.), Proceedings of the fifth conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 659-663). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Labrie, N. (2012). Strategic maneuvering in treatment decision-making discussions. Two cases in point. Argumentation, 26(2), 171-199.

Leff, M. C., & Mohrmann, G. P. (1993). Lincoln at Cooper Union. A rhetorical analysis of the text. In T. W. Benson (Ed.), Landmark essays on rhetorical criticism (pp. 173-187).

Lorenzen, P. (1960). Logik und Agon [Logic and agon]. In Atti del XII congresso internazionale di filosofia (Venezia, 12-18 settembre 1958), 4: Logica, linguaggio e comunicazione [Proceedings of the 12th international conference of philosophy (Venice, 12-13 September 1958), 4: Logic, language and communication] (pp. 187-194). Florence: Sansoni. Reprinted in P. Lorenzen & K. Lorenz (1978), Dialogische Logik [Dialogical logic] (pp. 1-8). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

McBurney, P., & Parsons, S. (2001). Chance discovery using dialectical argumentation. In T. Terano, T. Nishida, A. Namatame, S. Tsumoto, Y. Ohsawa & T. Washio (Eds.), New frontiers in artificial intelligence (pp. 414-424). Berlin: Springer.

Mercier, H. (2012). Some clarifications about the argumentative theory of reasoning. A reply to Santibáñez Yáñez (2012). Informal Logic, 32(2), 259-268.

Mercier, H., & Sperber, D. (2011). Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34, 57-111.

Næss, A. (1953). Interpretation and preciseness. A contribution to the theory of communication. Oslo: Skrifter utgitt ar der norske videnskaps academie.

Newman, R. P. (1961). Recognition of communist China? A study in argument. New York: Macmillan.

Nute, D. (1994). Defeasible logic. In D. M. Gabbay, C. J. Hogger & J. A. Robinson (Eds.), Handbook of logic in artificial intelligence and logic programming, 3. Non-monotonic reasoning and uncertain reasoning (pp. 353-395). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

O’Keefe, D. J. (2006). Pragma-dialectics and persuasion effects research. In: P. Houtlosser & M. A. van Rees (Eds.), Considering pragma-dialectics. A festschrift for Frans H. van Eemeren on the occasion of his 60th birthday (pp. 235-243). Mahwah, NJ-London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Palmieri, R. (2014). Corporate argumentation in takeover bids. Amsterdam-Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Perelman, C., & Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The new rhetoric. A treatise on argumentation. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. (English transl. by J. Wilkinson and P. Weaver of Ch. Perelman & L. Olbrechts-Tyteca (1958). La nouvelle rhétorique. Traité de l’argumentation. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. (3rd ed. Brussels: Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles)).

Pollock, J. L. (1987). Defeasible reasoning. Cognitive Science, 11, 481-518.

Prakken, H. (1997). Logical tools for modelling legal argument. A study of defeasible reasoning in law. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rahwan, I., Zablith, F., & Reed, C. (2007). Laying the foundations for a world wide argument web. Artificial Intelligence, 171(10-15), 897-921.

Reed, C. A., & Rowe, G. W. A. (2004). Araucaria. Software for argument analysis, diagramming and representation. International Journal on Artificial Intelligence Tools, 13(4), 961-979.

Rocci, A., & Zampa, M. (2015). Practical argumentation in newsmaking: The editorial conference as a deliberative activity type. In F. H. van Eemeren, E. Rigotti, A. Rocci, J. Sàágua & D. Walton (Eds.). Practical argumentation. Dordrecht: Springer.

Sanders, J. A., Gass, R. H., & Wiseman, R. L. (1991). The influence of type of warrant and receivers’ ethnicity on perceptions of warrant strength. In F. H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J. A. Blair & C. A. Willard (Eds.), Proceedings of the second international conference on argumentation(organized by the International Society for the Study of Argumentation at the University of Amsterdam, June 19–22, 1990), 1B (pp. 709-718). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Schiappa, E. (2002). Evaluating argumentative discourse from a rhetorical perspective. Defining ‘person’ and ‘human life’ in constitutional disputes over abortion. In F. H. van Eemeren & P. Houtlosser (Eds.), Dialectic and rhetoric. The warp and woof of argumentation analysis (pp. 65-80). Dordrecht etc.: Kluwer.

Schiappa, E. (2012). Defining marriage in California. An analysis of public and technical argument. Argumentation and Advocacy, 48(2), 211-215.

Schreier, M. N., Groeben, N., & Christmann, U. (1995). That’s not fair! Argumentative integrity as an ethics of argumentative communication. Argumentation, 9(2), 267-289.

Sillars, M. O. (1981). Investigating religious argument as a field. In G. Ziegelmueller & J. Rhodes (Eds.), Dimensions of argument. Proceedings of the second summer conference on argumentation (pp. 143–151). Annandale, VA: Speech Communication Association.

Tindale, C. W. (1999), Acts of arguing. A rhetorical model of argument. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Toulmin, S. E. (1958). The uses of argument. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. (updated ed. 2003).

Toulmin, S. E. (1972). Human understanding. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Toulmin, S. E. (2003). The uses of argument. Updated ed. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. (1st ed. 1958; paperback ed. 1964).

Verheij, B. (2003a). DefLog. On the logical interpretation of prima facie justified assumptions. Journal of Logic and Computation, 13(3), 319-346.

Verheij, B. (2003b). Dialectical argumentation with argumentation schemes. An approach to legal logic. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 11(1-2), 167-195.

Voss, J. F., Fincher-Kiefer, R., Wiley, J., & Ney Silfies, L. (1993). On the processing of arguments. Argumentation, 7(2), pp. 165-181.