ISSA Proceedings 2002 – On Toulmin’s Fields And Wittgenstein’s Later Views On Logic

1. Toumlin’s Fields: An Interpretative Conundrum

1. Toumlin’s Fields: An Interpretative Conundrum

Perhaps one of the most significant contributions to the study of argument and applied epistemology since Aristotle’s Topics was the introduction of the concept of a field of argument. Together with his Data-Warrant-Claim [D-W-C] model of argument, argument fields were Toulmin’s principal theoretical device in the constructive program he launched against the formal model of argument analysis and evaluation. The problem for the contemporary argumentation theorist is: How ought Toulmin’s concept of argument field to be interpreted, operationalized and applied in the projects of argument analysis and evaluation.

Willard has mused that the concept’s “most attractive feature … [is] that it can be made to say virtually anything” (1981: 21). To this, Zarefsky, has, more solemnly, added “there are so many different notions of fields that the result is conceptual confusion” (1982: 191). Before attempting to fathom this interpretive conundrum, it is perhaps best to situate the discussion by observing the significance and function of the concept of field in Toulmin’s overall theory of argument.

1.1 The Field-Dependency Thesis

Certainly, the most significant feature of argument fields is the thesis of field-dependency. Toulmin introduced the concept of field in answer to the question: “How far can justifcatory arguments take one and the same form, or involve appeal to one and the same standards, in all the different kinds of case which we have occasion to consider” (1958: 14)? On Toulmin’s account, there can be no single, abstract model that successfully captures the rational structure of all argument. Instead, while some features of arguments are field-invariant, others vary according to the field to which an argument belongs. For Toulmin, then, the first reason, that fields are significant to the study of argument is that theorists will be unable to create accurate models of argument unless we appreciate the nature, boundaries, and inner structure of argument fields. In fact, by failing to appreciate the field-dependency of certain features of argument, theorists fail to appreciate something fundamental about the very nature of justification.

What, then, is field-dependent? It is perhaps easier to ask what is not field-dependent. Because the structure of the D-W-C model is meant to capture “certain basic similarities of pattern and procedure [which] can be recognized … among justificatory arguments in general” (1958: 17), about the only thing does not vary according to an argument’s field is the overall D-W-C structure itself (1958: 175; 103; 119). By contrast, everything from an argument’s evidence (or data) (1958: 16), to warrants (1958: 100), to its backing (1958: 104) is field-dependent. Further, while the force of certain logical terms (e.g., modal terms and quantifiers) is field-invariant, the criteria according to which these terms are employed is field-dependent (1958: 29-35, 111-112)(i).

Now, the question is, what is radical about the thesis of field-dependency? Certainly, it is not revolutionary to claim that the data, evidence, or premises required of an argument will vary from one argument to the next. So, if Toulmin’s only claim is that the level of acceptability of a conclusion is, in part, a function of the level of acceptability of the premises, and that the considerations the will establish the truth or acceptability of particular premises need not be (and often are not) purely formal considerations, he will have no objection from the formalist.

Rather, the real bite of field-dependency is that argument features like warrant, backing and the criteria used to employ logical terms are irreducibly normative features of argument. They capture the evidentiary and justificatory relations constitutive of ‘good reasons’ and in so doing, embody the canons and standards by which arguments are properly evaluated(ii).

Yet, these are the very features of argument which vary from one field to the next. So, the more radical aspect of the field-dependency thesis is normative pluralism. Contrary to the aspirations of the formal logicians, there cannot be a single, universal and abstract model of all justification and hence of (good) arguments. Thus, one key thesis of theoretical import in Toulmin’s program is the claim that “we must judge each field of substantial arguments by its own relevant standards” (1958: 234). It is because arguments cannot all be evaluated by the same set of standards and norms that the theorist must appreciate the nature, boundaries, and inner structure of argument fields. Fields are, as it were, the natural kinds of evidentiary relations, and it is for this reason that fields capture something fundamental about the very nature of justification.

1.2 The Nature of Fields

The issue then of the nature of a field becomes a crucial question of Toulmin interpretation, and for any argumentation theorist seeking to present a model of argument informed by Toulmin’s views. Yet, as I mentioned earlier, there is hardly a consensus in the literature concerning field-theory. Any “conceptual confusion” surrounding the notion of a field is not helped by the fact that Toulmin himself seems to have actively resisted any rigorous attempt to operationalize the term. In fact, it would seem that each time Toulmin approached the topic of field is his own writing he gave his reader a different version of the concept.

For example, in The Uses of Argument, Toulmin defines “field” in two different ways. When Toulmin introduces the term in his first essay, he defines it as follows: “Two arguments will be said to belong to the same field when the data and conclusions in each of the two arguments are, respectively, of the same logical type: they will be said to come from different fields when the backing of the conclusions in each of the two arguments are not of the same logical type” (1958: 14)(iii). Yet, in the fourth essay of the book, Toulmin writes: “we introduced the notion of a field of arguments by referring to the different sorts of problem to which arguments can be addressed. If fields of argument are different, that is because they are addressed to different sorts of problems” (1958: 167). In the first case, “fields” are defined with reference to logical types, while in the second, fields are defined in terms of the sorts of problem to which arguments are addressed; yet, it is by no means apparent that these two defining concepts are synonymous. The two definitions are not obviously co-extensive, let alone intensionally equivalent, and Toulmin makes no effort to clarify his meaning.

Nor is this the extent of the interpretative problem.Toulmin first uses the term “field” in his doctoral thesis, The Place of Reason in Ethics, where he identifies fields with modes of reasoning (1953: 83; see also sects. 6.3, 6.7 and 13.7). Later, in An Introduction to Reasoning (the critical reasoning textbook written with Richard Rieke and Allan Janik) Toulmin seems to link fields of argument to the “locations or forums” in which arguments occur (Toulmin, Rieke and Janik 1979: 14). Variations in forum are themselves “a direct consequence of the functional differences between the needs of the enterprises concerned” (Toulmin, Rieke and Janik 1979: 15).Similarly, in Human Understanding, Toulmin seems to link fields with intellectual enterprises (1972: 85) and rational disciplines.

Any ambiguities (latent or manifest) in Toulmin’s own writing are only amplified and multiplied when one turns to the secondary literature for guidance. Given the context of this paper, I will not attempt here a review of the secondary literature(iv). Instead, I will only gesture in the direction of this body of secondary literature, noting that the debate surrounding field theory seems to have reached its peak more than two decades ago, when it was the central topic of the “Second Summer Conference of Argumentation” (sponsored by Speech Communication Association and the American Forensic Association). This was followed a year later by a special issue of the Journal of the American Forensic Association (edited by Charles Willard), devoted to the topic of argument fields. Suffice it to say, for present purposes, that, outside of a few basic features which are accepted by all models, the discussions captured in these volumes present a diversity rather than a consensus of opinion, and the conversational momentum seems to be that of divergence rather than convergence.

Finally, it is interesting that, ten years ago, when Toulmin himself had the occasion to address this audience (the 1992 ISSA Conference) he specifically did not speak to the notion of a field in an effort to clarify what he meant. About the closest Toulmin came in that talk to any discussing the notion of fields was his remark that “If I were writing the book [The Uses of Argument] today, I would broaden the context, and show that it is not just the ‘warrants’ and ‘backing’ that vary from field to field: even more, it is the forums of argumentation, the stakes, and the contextual details of ‘arguing’ as an activity” (1992: 9).

2. The Wittgenstein Connection

In this paper, I hope to reinvigorate the discussion surrounding Toulmin’s notion of fields. I hope to do so by exploring a provocative (if not lucrative) connection between Toulmin’s fields and Wittgenstein’s language-games. I shall try to show that these two theoretical constructs have at least enough superficial similarities as to make a thorough comparison a theoretically interesting endeavour. Further, I hope show how allowing Wittgenstein’s later views on logic to inform our approach to fields, some resolution may be cast upon the conundrums surrounding Toulmin interpretation and field theory itself.

First, though, what are some of the prima facie reasons that the theorist hoping to understand Toulmin might be tempted to turn to Wittgenstein as an interpretative guide?

I would certainly not be the first in observing a similarity, if not attributing an influence between Wittgenstein and Toulmin. At times, Toulmin has suffered criticism just because he came across as Wittgenstenian. O’Conner, for instance, wrote that The Uses of Argument “is novel in deriving its attitude from the later work of Wittgenstein rather than from better known sources of irrationalism” (1959: 244). But, there are other, perhaps better, reasons for examining the relationship between the thoughts of these two ‘unhappy logicians’.

In the first place, we know that Toulmin was attending Wittgenstein’s lectures while Toulmin was at Cambridge. Toulmin writes that he began his thesis work in the summer of 1946, and that the thesis was finished in February 1948 (1953: viii). Wittgenstein, on the other hand, stopped lecturing when he returned from Vienna in April of 1947 (Monk 1990: 518). Monk, in his biography of Wittgenstein The Duty of Genius, informs us that Wittgenstein had finished the Philosophical Investigations in 1945-46 (1990: 483), so we may assume that Wittgenstein would have been working this material into his lectures during this period. While Wittgenstein was lecturing primarily on the philosophy of psychology at the time, Monk writes that Wittgenstein “devoted a good deal of time in these lectures to an attempt to describe his philosophical method” (Monk 1990: 501).

Secondly, throughout his various works, Toulmin makes several acknowledgements to Wittgenstein, as well as other Cambridge professors. In the acknowledgements to The Place of reason in Ethics Toulmin writes that “many of the problems [dealt with in the book] would have been beyond my power but for the light which I derived from the lectures of Dr. Ludwig Wittgenstein” (1953: xiii). It should be mentioned, though, that Toulmin does not make an acknowledgement to Wittgenstein in either The Uses of Argument, or Human Understanding.

Finally, there are unmistakable similarities between the methods employed by Toulmin, especially in his earlier works, and those espoused by Wittgenstein. To cite just one example, Toulmin has continually advocated a methodology by which arguments are considered in the context of their human situation. As early as The Place of Reason in Ethics, Toulmin asserts an “intimate connection between the logic of a mode of reasoning and the activities in which the reasoning plays its primary part” (1953: 81). This is resonant with Wittgenstein’s claim that “Language-games are a clue to the understanding of logic” (1979: 12). Yet, by starting with language in use, Toulmin has raised the ire of some of his more unsympathetic commentators. O’Conner, for instance, remarked on Toulmin’s “inordinate regard for vulgar usage” (1959: 244), while Sikora remarked that “his [Toulmin’s] ‘logic’ is essentially a phenomenology of acceptable arguments without explanation as to why these are acceptable” (1959: 374).

Having touched upon some of the circumstances that brought Wittgenstein and Toulmin together, let us proceed to the proximity of their ideas. To do so, we must explore some of the features of Wittgenstein’s later views on logic.

3. Wittgenstein’s Later Views on Logic(v)

When Wittgenstein finished the Tractatus, he brazenly proclaimed that “the problems [occupying philosophy] have in essentials been finally solved” (1922: 29). Thereupon, he abandoned philosophical inquiry until 1927-28 when took up discussions with members of the Vienna Circle he and attended a lecture by the intuitionist mathematician Brouwer (Monk 1990: 241-251). By 1929 Wittgenstein had returned to Cambridge, and philosophy. Over the course of the development of his later philosophy, Wittgenstein came to believe that a number of views he espoused in the Tractatus, a number of the assumptions traditionally underpinning a rigorous, formalist approach to logic (as espoused by, e.g., Frege and Russell) were either false or untenable.

Specifically, Witgenstein came to reject the view that logic was a single, universal and abstract model of all justification and hence of (good) arguments. At one point in the Tractatus, Wittgenstein spoke of “the all-embracing logic” which is “an infinitely fine network” and “the great mirror [of the world” (1922: 5.511). Yet, by 1932, Wittgenstein would tell his class in Cambridge that “Russsell’s calculus is one calculus among others” (1979: 13). By the time Wittgenstein wrote On Certainty he would go so far as to claim that “everything descriptive of a language-game is part of logic” (1969: §55). So, what changed?

3.1 The Logic of the Tractatus

In the Tractatus, Wittgenstein held what has been called the ‘picture theory’ of language: “A proposition is a picture of reality” (1922: 4.01). On this account, language is given the job of representing or picturing reality. Language is, as it were, a picturing of facts (1922: 2.1, 2.141), and “a proposition is the description of a fact” (1922: 4.023).

Logical form is a property that is shared by all propositions and reality (1922: 2.1514), that allows any proposition to represent reality (1922: 2.16, 2.161) either correctly or incorrectly (1922: 2.17, 2.171). It is through this property that language is attached directly to reality (1922: 2.1511).

Facts are the natural kinds of the logical universe, and are those things into which the world divides (1922: 1.2). Moreover, they are logically (or metaphysically) independent. “Any one can either be the case or not be the case and everything else will remain the same” (1922: 1.21). “Atomic facts are independent of one another” (1922: 2.061, 2.062).

The independence of atomic facts has a profound technical significance for the logical calculus. Since propositions are descriptions of facts, the truth or falsity of a proposition is tied directly to the obtaining or non-obtaining (existence or non-existence) of the corresponding fact (1922: 4.25). As such, “the truth possibilities of the elementary propositions mean the possibilities of the existence and non-existence of the atomic facts” (1922: 4.3). On the basis of this insight, Wittgenstein invented the “truth-table” schemata for representing not only the possibilities of the logical combinations of propositions (and their corresponding facts) (1922: 4.31), but also for the truth-functional semantics of the logical operators (1922: 4.431 – 5.132).

3.2 The Problem of Determinate Exclusion

The problem with the Tractarian picture of logic that Wittgenstein discovered in 1929 was the following: Since atomic propositions ascribe properties that admit of degree, and this feature that cannot be removed by any symbolism, atomic propositions cannot be logically independent of each other. This, Wittgenstein realized, quickly brought down significant structural features of the Tractarian edifice.

It is integral to the Tractarian picture that the semantics for the truth-functional operators (i.e., “not,” “or,” “and,” “if … then,” and their stylistic variants) are given by the truth-tables, and that these truth-tables accurately capture all and only the logical possibilities pertaining to the propositions involved. As such, it is necessary that these truth-functional operators be able to combine any two well-formed formulae (we will deal here exclusively with atomic propositions) and that the truth-tables, in giving the semantics for the truth-functional operator, give the truth-functional result of the combination of the propositions.Yet, if atomic propositions are not logically independent, this cannot be.

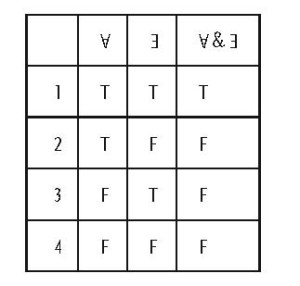

Let us consider the same example that Wittgenstein presents in Some Remarks on Logical Form (RLF). Consider the truth-table for “and” (“&”):

Wittgenstein observes that, while the thesis that the above truth table gives the proper semantics for “and” requires that the propositional variables A and E be able to take any proposition as their argument, in actual fact, they cannot. In RLF, Wittgenstein considers the examples of two propositions, each of which asserts the existence of a different colour at single place in our visual field at the same time (1929:168). (Following Wittgenstein, I will call these two propositions ‘RPT’ for “the colour R is in the place P at time T” and ‘BPT’ for “the colour B is in the place P ant time T” (ibid.).) As Wittgenstein notes, “it is a characteristic of these properties that one degree of them excludes any other” (1929: 167).

That is, with the two propositions ‘RPT’ and ‘BPT’, “the top line [ valuation 1 of the truth-table] ‘TTT’ must disappear, as it represents an impossible combination” (1929: 170). Moreover, it is of no help to attempt to ‘patch’ the system, by trying to amend the truth-value of “RPT & BPT” on valuation 1 from “T” to “F”. Wittgenstein claims that such an amended truth-table is not merely incorrect, but that it is “nonsense, as the top line [i.e., valuation 1], ‘T T F,’ gives the proposition [i.e.,“RPT & BPT”] a greater logical multiplicity than that of the actual possibilities” (ibid.)(vi). Importantly, Wittgenstein argues that the relationship of determinate exclusion that obtains between the two propositions RPT and BPT is a logical and not a contingent feature. “It is a characteristic of these properties that one degree of them excludes any other. One shade of colour cannot simultaneously have two different degrees of brightness or redness, a tone not two different strengths, etc. And the important point here is that these remarks do not express an experience but are in some sense tautologies” (1929: 167). For example, when we consider the formuale “RPT ¬BPT” or “¬ (RPT & BPT)” these expressions are true on every (logically) possible valuation, and as such, are tautologies (1922: 4.46). As such, the logical character of relations like determinate exclusion is equivalent (e.g., in terms of necessity or impossibility) with formal logical relations. That is, relations like that of determinate exclusion are a kind of logical relation arising, not from the meanings of the logical operators, but from the meanings of non-logical terms.

This, in turn, dramatically alters the general nature of inference as it is conceived on a formalist model. As Wittgenstein told Waismann and Schlick, “All this I did not yet know when I was writing my work [the Tractatus]: at that time I thought that all inference was based on tautological form. At that time I had not yet seen that an inference can also have the form: This man is 2m tall, therefore he is not 3m tall” (Waismann 1979: 63; see also Shanker 1984, 57). Yet, as Wittgenstein quickly saw, there is no way to capture all such inferences in a single calculus, let alone a practical or axiomatizable one.

3.3 From Propositional Systems to Language Games

The immediate consequences of determinate exclusion are striking. Not only do examples such as this defeat the thesis of the independence of atomic propositions. But with the fall of the independence thesis, any aspiration of a single, unified calculus capable of capturing all justificatory relationships, and based solely on the semantics of purely logical terms is also dashed. The logician finds not a single, rarified abstract and universal calculus, but instead a series of local logical relations which hold between whole sets of concepts which come, as it were, pre-packaged.

This realization, for Wittgenstein marked the birth of the concept of a ‘system of propositions’ (satzsysteme). In his discussing this point with Waismann and Schlick in 1929, Wittgenstein said:

“Once I wrote, ‘A proposition is laid against reality like a ruler. Only the end-points of the graduating lines actually touch the object that is being measured.’ [TLP, 2.1512-2.15121] I now prefer to say that a system of propositions is laid against reality like a ruler. What I mean is the following. If I lay a ruler against a spatial object, I lay all the graduating lines against it at the same time. … It is not the individual graduating lines that are laid against it, but the entire scale. If I know that the object extends to graduating line 10, I also know immediately that it does not extend to graduating lines 11, 12, and so forth. The statements describing for me the length of an object form a system, a system of propositions. Now, it is such an entire system of propositions that is compared with reality, not a single proposition. If I say, for example, that this or that point in the visual field is blue, then I know not merely that, but also that this point is not green, nor red, nor yellow, etc. I have laid the entire colour scale against it at one go. This is also the reason why a point cannot have different colours at the same time. For when I lay a system of propositions against reality, this means that in each case there is only one state of affairs that can exist, not several – just as in the spatial case” (Waismann 1979: 64; see also Shanker 1984: 57).

Wittgenstein here realized two things: First, the meanings of the constituents of a system of propositions are inter-related in unique ways as compared with the propositions of a different system. Second, within a single natural language, there are many different and independent systems of propositions. It is for this reason that “Russell’s calculus is one calculus among others” (1979: 13).

The relations that hold between the propositions of a single system Wittgenstein came to call ‘grammatical’ (or sometimes ‘internal’) relations, and they are a species of fully-fledged logical relations. Given that grammatical relations arise out of, and are grounded in the meanings of the terms and propositions which they relate, the proper study of logic becomes a study of meaning.

While Wittgenstein was developing these views on the relationship between the study and domain of logic and the semantics of non-logical terms, he was simultaneously developing his views that the semantics of our language can be properly given only when we consider language in use. In 1932, Wittgenstein would introduce his students to his thesis that “the meaning of a word is its use in the language” (1958: § 43) saying “ ‘How is a word used?’ and ‘What is the grammar of the word?’ I shall take to be the same question” (1979: 3). Finally, it must be remembered that Wittgenstein introduced the methodological device of ‘language-games’ in this same series of 1932 lectures (Monk 1990: 330). Language-games are a device by which we may both properly situate and fully isolate the normal use of a single expression in a language, and, by so doing, may properly study its logical grammar – i.e., the grammatical relations governing its use and so constituting its meaning. As such, “Language-games are a clue to the understanding of logic. Since what we call a proposition is more or less arbitrary, what we call logic plays a different role from that which Russell and Frege supposed” (Wittgenstein1979: 12-13). Moreover, it is for this reason that “everything descriptive of a language-game is part of logic” (Wittgenstein 1969: §56, see also §82).

Now, the picture that we have been left with should appear vaguely familiar. Wittgenstein’s position regarding normative pluralism is rather comparable to Toulmin’s own. Not only is there no single calculus capable of modeling all justificatory relations, but there is a plurality of ‘logical regions’ (for lack of a better term), each of which are governed by their own set of norms and standards. These standards not only form the canons of rational evaluation for the region, but are based on some kind of internal properties or relations that obtain between the constituents of the region itself. That is, both fields and language-games appear to be the natural kinds of the justificatory world

4. Field Theory: The Conundrum Revisited

So, in light of the above considerations, how might we benefit from an approach to field-theory that is informed by Wittgenstein’s later views on logic?

If I am right in an unreserved and unqualified way, then we may have a solution to the interpretative conundrum surrounding field theory. After all, if I am right, then questions concerning the nature, boundaries and inner structure of fields may be simply reduced to similar questions concerning language-games.

People familiar with the discussion on this latter set of questions may not think that my solution does them any favours! In the first place, logic will remain a messy business. As Russell remarked about Wittgenstein’s later views (again in the 1930 letter to G.E. Moore) “His [Wittgenstein’s] theories are certainly important and certainly very original. Whether they are true, I do not know; I devoutly hope they are not, as they make mathematics and logic almost incredibly difficult.” (1967: 297-98). What Russell neglected to mention is the fact that Wittgenstein’s later views on logic effectively leave the old, formal structure both in place and operational. Neither the foundation nor the effectiveness of the formal calculus is challenged by Wittgenstein’s later views – only its comprehensiveness, and its exclusive entitlement to the endorsement of ‘logical certainty’.

Further, on the good side, Wittgenstein seems to give the theorist a much more definite and consistent account of language-games than what Toulmin has provided when it comes to fields. Admittedly, both start from a consideration of the situated use of language in a normal circumstance. But, Wittgenstein’s account seems to provide, additionally, that the nature, boundaries and inner structure of language-games are logical in character, and are determined according to the meanings – the grammatical relations – of the non-logical terms employed within the language-game.

Next, if consensus is some reason to think that my reading of Toulmin is not far from the mark, then I have at least some support from the secondary literature. One of Toulmin’s earliest commentators, Otto Bird, made a similar observation in his review of The Uses of Argument. Bird wrote:

“The examples make it clear that Toulmin is primarily concerned with arguments which derive at lease some of their argumentative force from relations of meaning among non-logical words… This is to say, in terms of the medieval logical analysis, that he is concerned with material rather than with formal consequence. ‘Formal’ in this connection has to do with the syncategorematic terms, such as the connectives, ‘and’, ‘or’, ‘if … then’, ‘not’, and the quantifiers ‘all’ and ‘some’, whereas ‘material’ refers to the categorematic terms. The logical study of material consequence, i.e., of logical consequence that depends in some way upon the categorematic terms, was for medieval formal logic primarily the study of the Topics” (1959: 536).

It is, perhaps, no small coincidence that one of the examples Toulmin uses is making his case for the field-variability of warrants is the argument “Harry’s hair is red, so it is not black” (1958: 97). Nor was Bird the only reviewer to comment on this feature. Sikora, writing for New Scholasticism, wrote that “The chief significance of …[The Uses of Argument] is in its return to the problems, often greatly neglected in modern logic, of material logic” (1959: 374).

In fact, it was Bird who first characterized Toulmin’s work as “The Re-discovery of the Topics” – a characterization which Tolmin has later taken as his own. In 1982, speaking at the University of Michigan on the topic of “Logic and the Criticism of Arguments,” Toulmin said the following:

“By the time I wrote The Uses of Argument,… logic had been completely identified with ‘analytics,’ and Aristotle’s Topics was totally forgotten: so much so that, when I wrote the book, nobody realized that it bore the same relation to the Topics that Russell and Frege’s work bore to the traditional ‘analytic’ and ‘syllogistic.’ Only in retrospect is it apparent that – even though sleepwalkingly – I had rediscovered the topics of the Topics” (1989 [1982]: 380).

Regrettably, though, this endorsement from Toulmin may not be sufficient to secure my interpretive strategy. Problematically, Toulmin disavows the thesis that the only justificatory cement of fields is the semantic relationships of non-logical terms. Instead, Toulmin claims that, “For, in the case of genuinely substantial arguments, probability depends on quite other things than semantic relations” (1958: 153).

So, as I began this talk with a problem, I shall now close it with a different one. Toulmin devised his D-W-C model and the notion of argument fields to provide an account of how arguments may be analysed and evaluated so as to capture those arguments whose evidentiary structure and justificatory success does not reside in their formal properties. Wittgenstein has provided an additional layer to the logical analysis that may be applied to arguments. By directing us, with Toulmin, back to the Topics and the study of material implication, Wittgenstein invites us to consider arguments whose justification relies on the meaning of the non-logical terms employed in the argument. The question then remains, what other fields of justificatory argument are there, and by what means shall we approach their study so as to determine their nature, boundaries and inner structure.

NOTES

i. Toulmin explains the force / criteria distinction as follows: “The meaning of a modal term … has two aspects: … the force of the term and the criteria for its use. By the ‘force’ of a modal term I mean the practical implications of its use … This force can be contrasted with the criteria, standards, grounds and reasons, by reference to which we decide in any context that the use of a particular term is appropriate” (1958: 30).

ii. Take warrants for instance. Toulmin asserts that warrants “correspond to the practical standards or canons of argument” (1958: 98).

iii. It should be observed that Toulmin’s definition of “field” in terms of logical type is notoriously problematic. Willard as argued that “type theories are inappropriate analytical tools for argumentation and unsuitable bases for defining argument fields” (1981: 144). Earlier, O’Conner made a more general criticism of Toulmin’s move here, saying that “He [Toulmin] explains it [the notion of ‘field’] by reference to the concept of ‘logical type’. But if ‘type’ is used here in an untechnical sense, it is unexplanatory (and unexplained). And, if the use is technical, it is surprising to find one of Toulmin’s crucial concepts resting on a technicality of the formal logic that he believes to be quite irrelevant to serious argument” (1959: 244).

iv. I have, though, included as comprehensive a bibliography as my current research has produced.

v. I first became aware of Wittgenstein’s position as it is presented and discussed throughout section 3 on reading S.G. Shanker (1984).

vi. Instead of saying that the expression “RPT & BPT” is false, one might want to say that it is senseless (in that it does not represent any logical combination of possibilities), just as Wittgenstein would call a contradiction senseless. Importantly, Wittgenstein would not want to say that the expression “RPT & BPT” is a contradiction – rather, the two expressions “RPT” and “BPT” exclude each other. Wittgenstein introduces this distinction to mark the difference that atomic propositions cannot contradict each other (in the usual sense), although they can exclude each other. So, Wittgenstein calls the (amended) truth-table for “RPT & BPT” nonsense, and not the expression “RPT & BPT” itself. I would like to acknowledge the observations of Eric Krabbe, Daniel Cohen and Michael Gilbert who pointed out this correction to me in the discussion following my paper presentation.

REFERENCES

Toulmin Sources:

Abelson, Raziel. (1961). In Defense of Formal Logic. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 21, 333-346.

Bird, Otto. (1961). The Re-discovery of the Topics: Professor Toulmin’s Inference Warrants. Mind, 70, 534-539.

Brockriede, Wayne & Douglas Ehninger. (1992). Toulmin on Argument: An Interpretation and Application. Quarterly Journal of Speech 46 (1960): 44-53.

Rpt. in Contemporary Theories of Rhetoric. Ed. Richard L. Johannsen. New York:

Campbell, John Angus. (1981). Historical Reason: Field as Consciousness. In: George Ziegelmueller & Jack Rhodes (Eds.), Dimensions of Argument: Proceedings fo the Second Summer Conference on Argumentation, Annandale, VA.: Speech Communication Association.

Castaneda, Hector Neri. (1960). On a Proposed Revolution in Logic. Philosophy of Science, 27, 279-292.

Cooley, J.C. (1959). On Mr. Toulmin’s Revolution in Logic. Journal of Philosophy, 56(7), 297-319.

Cox, J. Robert. (1981). Investigating Policy Arguments as a Field. In: George Ziegelmueller & Jack Rhodes (Eds.), Dimensions of Argument: Proceedings fo the Second Summer Conference on Argumentation, Annandale, VA.: Speech Comunication Association.

Ehniger, Douglas & Wayne Brockriede. (1963). Decision by Debate. New York: Dodd, Mead.

Fisher, Walter R. (1981). Good Reasons: Fields and Genre. In: George Ziegelmueller & Jack Rhodes (Eds.), Dimensions of Argument: Proceedings fo the Second Summer Conference on Argumentation, Annandale, VA.: Speech Communication Association.

Fulkerson, Richard. (1991). Some Uses and Limitations of the Toulmin Model of Argument. In: William E. Tanner & Betty Kay Seibt (Eds.), The Toulmin Method: Exploration and Controversy. Arlington: Liberal Arts Press, pp. 80-96.

Fulkerson, Richard. (1996). The Toulmin Model of Argument and Teaching Composition. In: Barbara Emmel, Paula Resch & Deborah Tenny (Eds.), Argument Revisited, Argument Redefined: Negotiating Meaning in the Composition Classroom. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage, pp. 45-72.

Gaonkar, Dilip Parameshwar. (1982). Foucault on Discourse: Methods an Temptations. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 18(4), 246-257.

Goodnight, G. Thomas. (1982). The Personal, Technical and Public Spheres of Argument: A Speculative Inquiry into the Art of Public Deliberation. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 18(4), 214-227.

Goodnight, G. Thomas. (1993). Legitimation Inferences: An Additional Component for the Toulmin Model. Informal Logic 15, 41-52.

Gronbeck, Bruce E. (1981). Socio-cultural Notions of Argument Fields: A Primer. In: George Ziegelmueller & Jack Rhodes (Eds.), Dimensions of Argument: Proceedings fo the Second Summer Conference on Argumentation, Annandale, VA.: Speech Communication Association.

Hample, Dale. (1977). The Toulmin Model and the Syllogism. Journal of the American Forensic Association 14, 1-9.

Hample, Dale. (1981). What is a Good Argument? In: George Ziegelmueller & Jack Rhodes (Eds.), Dimensions of Argument: Proceedings fo the Second Summer Conference on Argumentation, Annandale, VA.: Speech Communication Association.

Hart, Rodrick P. (1990). Toulmin and Reasoning. In Modern Rhetorical Criticism, Glenview Il.: Scott Foresman, pp. 138-150.

Johnson, R.H. (1981). Toulmin’s Bold Experiment. Informal Logic Newsletter, 3 (2) 16-27 (part I); 3(3) 13-19 (part II).

King-Farlow, J. (1973). Toulmin’s Analysis of Probability. Theoria, 29, 12-26.

Klumpp, James F. (1981). A Dramatistic Approach to Fields. In George Ziegelmueller & Jack Rhodes (Eds.), Dimensions of Argument: Proceedings fo the Second Summer Conference on Argumentation, Annandale, VA.: Speech Communication Association.

Lewis, Albert L. (1972). Stephen Toulmin: A Reappraisal. Central States Speech Journal, 23, 48-55.

Manicas, Peter T. (1966) On Toulmin’s Contribution to Logic and Argumentation. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 3, 83-94.

Rpt. in 1971 Richard L. Johansenn (Ed.), Contemporary Theories of Rhetoric: Selected Readings, New York: Harper, 256-70.

McKerrow, Ray E. (1973). Rhetorical Logoi: The Search for A Universal Criterion of Validity,” SCA Convention Paper.

McKerrow, Ray E. (1977). Rhetorical Validity: An Analysis of Three Perspectives on the Justification of Rhetorical Argument. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 13, 133-141.

McKerrow, Ray E. (1980). Argument Communities: A Quest for Distinctions. In: Jack Rhodes & Sara Newell (Eds.), Proceedings of the [First] Summer Conference on Argumentation. Falls Church, VA.: Speech and Communication Association and American Forensic Association, pp. 214-227.

McKerrow, Ray E. (1980). On Fields and Rational Enterprises: A Reply to Willard. In: Jack Rhodes & Sara Newell (Eds.), Proceedings of the [First] Summer Conference on Argumentation. Falls Church, VA.: Speech and Communication Association and American Forensic Association, pp. 401-413.

McKerrow, Ray E. (1980). Validating Arguments: A Phenomenological Perspective. SCA Convention Paper.

McKerrow, Ray E. (1981). Field Theory: A Necessary Concept? Speech Communication Association convention (Annaheim California, November 1981.)

McKerrow, Ray E. (19??). Rationality and Reasonableness in Theory of Argument. In: J. Robert Cox & Charles A. Willard (Eds.), Advances in Argumentation Theory and Research. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press; American Forensic Association.

Olson, Gary A. (1993). Literary Theory, Philosophy of Science and Persuasive Discourse: Thoughts from a neo-premodernist. Journal of Advanced Composition 32(2), 283-309.

Pratt, J.M. (1970). The Appropriateness of A Toulmin Analysis of Legal Argumentation. Speaker and Gavel, 7, 133-137.

Reinard, J.C. (1984). The Role of Toulmin’s Categories of Message Development in Persuasive Communication: Two Experimental Studies on Attitude Change. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 20, 206-223.

Rowland, Robert C. (1981). Argument Fields. In: George Ziegelmueller & Jack Rhodes (Eds.), Dimensions of Argument: Proceedings fo the Second Summer Conference on Argumentation, Annandale, VA.: Speech Communication Association.

Rowland, Robert C. (1982). The Influence of Purpose on Fields of Argument. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 18(4), 228-245.

Scott, Robert L. (1970). Toulmin Ten Years Later: Time for a Change. Central States Speech Convention Paper.

Sillars, Malcolm O. (1981). Investigating Religious Argument as a Field. In: G. Ziegelmueller & J. Rhodes (Eds.), Dimensions of Argument: Proceedings of the Second Summer Conference on Argumentation, Annandale, VA: Speech Communication Association, pp. 143-151.

Toulmin, S. E. (1953). An Examination of the Place of Reason in Ethics. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Toulmin, S. E. (1958). The Uses of Argument, Cambridge University Press, New York.

Bird, Otto. (1959). Review of S.E. Toulmin The Uses of Argument. Philosophy of Science, 9, 185-189

Collins, J. (1959). Review of S.E. Toulmin The Uses of Argument. Cross Currents 9, 179.

Cowan, J.L.: 1964, ‘Review of S.E. Toulmin The Uses of Argument – An Apology for Logic’, Mind 73, 27-45.

Everyday Logic, Review of S.E. Toulmin The Uses of Argument. The Times Literary Supplement, 9 May 1958, 258.

Hardin, C.L. (1959). Review of S.E. Toulmin The Uses of Argument. Philosophy of Science 26, 160-163.

Koerner, Stephen. (1959). Review of S.E. Toulmin The Uses of Argument. Mind, 68, 425-427.

Mason, D. (1961). Review of S.E. Toulmin The Uses of Argument. Augustiniana, 1, 206-209.

O’Connor, D.J. (1959). Review of S.E. Toulmin The Uses of Argument. Philosophy, 34, 244-45.

Sikora, J.J. (1959). Review of S.E. Toulmin The Uses of Argument. New Scholasticism, 33, 373-374.

Urmson, J.O. (1958). The Province of Logic: Review of S.E. Toulmin The Uses of Argument. Nature, 182, 212-13.

Will, Frederick L. (1960). Review of S.E. Toulmin The Uses of Argument. Philosophical Review, 69, 399-403.

Toulmin, S.E. (1953). The Philosophy of Science: An Introduction.

Toulmin, S.E. (1970). Reasons and Causes. In: Robert Borger & Frank Cioffi (Eds.), Explanation in the Behavioural Sciences, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1-26. [“Comment”, by R.S. Peters follows, pp. 27-41; “Reply” by Toulmin follows Peters, pp. 42-48.]

Toulmin, S.E. (1973). Rationality and the Changing Aims of Inquiry. In: Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress for Logic, Methodology, and Philosophy of Science, North Holland, Amsterdam.

Toulmin, S.E. (1972). Human Understanding: The Collective Use and Evolution of Concepts. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Toulmin, S.E. (1988). The Recovery of Practical Philosophy. American Scholar, 57, 337-352.

Toulmin, S.E. (1989). Logic and the Criticism of Arguments. In: James Golden, Goodwin Berquist & William Cloeman (Eds.), The Rhetoric of Western Thought, 4th ed., Kendal/Hunt Publishing Company, Iowa, pp. 374-388.

Toulmin, S.E. (1992). Logic, Rhetoric and Reason: Redressing the Balance. In: Frans van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst, J. Anthony Blair & Charles A. Willard (Eds.), Argumentation Illuminated: Proceedings of the Second ISSA Conference on Argumentation, Sic Sat, Amsterdam, pp. 3-11.

Toulmin, S.E. (2001). Return to Reason. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Toulmin, S.E., Richare Rieke & Allan Janik. (1979). An Introduction to Reasoning. New York: Macmillan.

Trent, J.D. (1968). Toulmin’s Model of an Argument: An Examination and Extension. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 54, 252-259.

Wenzel, Joseph W. (1982). On Fields of Argument as Propositional Systems. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 18(4), 204-213.

Willard, Charles A. (1978). A Reformulation of The Concept of Argument: The Constructivist / Interactionist Foundations of a Sociology of Argument. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 14, 121-140.

Willard, Charles A. (1980). Some Questions about Toulmin’s View of Argument Fields. In Jack Rhodes & Sara Newell (Eds.), Proceedings of the [First] Summer Conference on Argumentation, Falls Church, VA.: American Forensic Association and Speech Communication Association, pp. 348-400.

Willard, Charles A. (1981). Argument Fields: A Cartesian Meditation. In: George Ziegelmueller & Jack Rhodes (Eds.), Dimensions of Argument: Proceedings fo the Second Summer Conference on Argumentation, Annandale, VA.: Speech Communication Association.

Willard, Charles A. (1981). Argument Fields and Theories of Logical Types. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 17(3), 129-145.

Willard, Charles A. (Guest Ed.). (1982). Journal of the American Forensic Association Special Issue: Symposium on Argument Fields, 18(4), 191-257.

Willard, Charles A. (1983). Argumentation and the Social Grounds for Knowledge. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press.

Willard, Charles A. (… ). Argument Fields: A Constructivist / Interactionist View. In: J. Robert Cox & Charles A. Willard (Eds.), Argumentation Theory and Research (Carbondale, Southern Illinpois University Press, American Forensic Association.

Wohlrapp, H. (1987). Toulmin’s theory and the dynamics of argumentation. In: F.H. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J.A.Blair & Charles A Willard (Eds.), Argumentation: Perspectives and Approaches. Proceedings of the Conference on Argumentation 1986, Dordrecht/Providence: Foris Publications, PDA 3A, pp. 327-335.

Zarefsky, David. (1981). ‘Reasonableness’ in Public policy Argument: Fields as Institutions. In George Ziegelmueller & Jack Rhodes (Eds.), Dimensions of Argument: Proceedings fo the Second Summer Conference on Argumentation, Annandale, VA.: Speech Communication Association.

Zarefsky, David. (1982). Persistent Questions in the Theory of Argument Fields. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 18(4), 191-203.

Wittgenstein Sources:

Monk, Ray. (1990). Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius. London: Vintage.

Russell, Bertrand. (1967). The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell. London: Unwin Books, pp. 294-307.

Shanker. S.G. (1984). Wittgenstein’s Solution of the ‘Hermenutic Problem’. Conceptus, 18(44), 50-61.

Waismann, Friedrich. (1979). Ludwig Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle. Schulte & McGuinnes (Trans.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. (1922). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Wittgensetin, Ludwig. (1929). Some Remarks on Logical Form. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, suppl. vol. IX, 162-171.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. (1958). Philosophical Investigations, 2nd ed. G.E.M. Anscombe (Trans.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. (1969). On Certainty. G.E.M. Anscombe and G.H. von Wright (eds.). Denis Paul and G.E.M. Anscombe (Trans.). New York: Harper & Row.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. (1979). Wittgenstein’s Lectures – Cambridge, 1932-35: From the Notes of Alice Ambrose and Margaret Macdonald. Alice Ambrose (ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

04-03-2024 ~ Political polarization—the inability of groups such as political parties, religious sects, and cultural identity groups to cooperate even in basic, essential matters—has been a worry and a threat since American democracy began, and for many centuries before. James Madison called it “faction,” and in The Federalist, No. 10, he

04-03-2024 ~ Political polarization—the inability of groups such as political parties, religious sects, and cultural identity groups to cooperate even in basic, essential matters—has been a worry and a threat since American democracy began, and for many centuries before. James Madison called it “faction,” and in The Federalist, No. 10, he