ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Implicitness Functions In Family Argumentation

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Argumentation is a mode of discourse in which the involved interlocutors are committed to reasonableness, i.e. they accept the challenge of reciprocally founding their positions on the basis of reasons (Rigotti & Greco Morasso 2009). Even though during everyday lives of families argumentation proves to be a very relevant mode of discourse (Arcidiacono & Bova, in press; Arcidiacono et al., 2009), traditionally other contexts have obtained more attention by argumentation theorists: in particular, law (Feteris, 1999, 2005), politics (Cigada, 2008; Zarefsky, 2009), media (Burger & Guylaine, 2005; Walton, 2007), health care (Rubinelli & Schulz, 2006, Schulz & Rubinelli, 2008), and mediation (Jacobs & Aakhus, 2002; Greco Morasso, in press).

This paper focuses on the less investigated phenomenon of argumentative discussions among family members. More specifically, I address the issue of the implicitness and its functions within argumentative discussions in the family context. Drawing on the Pragma-dialectical approach to argumentation (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1984, 2004), the paper describes how the implicitness is a specific argumentative strategy adopted by parents during dinner conversations at home with their children.

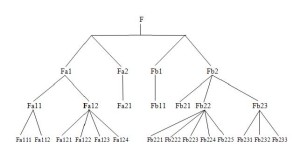

In the first part of the paper I will present a synthetic description of the basic properties of family dinner conversations, here considered a specific communicative activity type[i]. Subsequently, the current landscape of studies on family argumentation and the pragma-dialectical model of critical discussion will be taken into account in order to provide the conceptual and methodological frame through which two case studies are examined.

2. Family dinner conversations as a communicative activity type

Dinnertime has served as a relevant communicative activity type for the study of family interactions. Its importance as a site of analysis is not surprising since dinner is one of the activities that brings family members together during the day and serves as an important occasion to constitute and maintain the family roles (Pan et al., 2000). Indeed, family dinner conversations are characterized by a large prevalence of interpersonal relationships and by a relative freedom concerning issues that can be tackled (Pontecorvo & Arcidiacono, 2007).

Several studies have contributed to the understanding of the features that constitute the dinnertime event, the functions of talk that are performed by participants, and the discursive roles that family members take up (Davidson & Snow, 1996; Pontecorvo et al., 2001; Ochs & Shohet, 2006). For instance, Blum-Kulka (1997) identified three contextual frames based on clusters of themes in family dinner conversations: An instrumental dinner-as-business frame that deals with the preparation and service of food; a family-focused news telling frame in which the family listens to the most recent news of its members; a world-focused frame of non-immediate concerns, which includes topics related to the recent and non-recent past and future, such as talk about travel arrangements and complaints about working conditions. In addition, she identified three primary functions of talk at dinnertime: Instrumental talk dealing with the business of having dinner; sociable talk consisting of talking as an end in itself; and socializing talk consisting of injunctions to behave and speak in appropriate ways. All these aspects constitute a relevant concern to focus on dinnertime conversations in order to re-discover the crucial argumentative activity that is continuously developed within this context.

In the last decade, besides a number of studies which highlight the cognitive and educational advantages of reshaping teaching and learning activities in terms of argumentative interactions (Mercer, 2000; Schwarz et al., 2008; Muller Mirza & Perret-Clermont, 2009), the relevance of the study of argumentative discussions in the family context is gradually emerging as a relevant field of research in social sciences.

The family context is showing itself to be particularly significant in the study of argumentation, as the argumentative attitude learnt in family, above all the capacity to deal with disagreement by means of reasonable verbal interactions, can be considered “the matrix of all other forms of argumentation” (Muller Mirza et. al., 2009, p. 76). Furthermore, despite the focus on narratives as the first genre to appear in communication with young children, caregiver experiences as well as observations of conversations between parents and children suggest that family conversations can be a significant context for emerging argumentative strategies (Pontecorvo & Fasulo, 1997). For example, a study done by Brumark (2008) revealed the presence of recurrent argumentative features in family conversations, as well as the association between some argumentative structures and children’s ages. Other works have shown how families of different cultures can be characterized by different argumentative styles (Arcidiacono & Bova, in press) and how specific linguistic indicators can trigger the beginning of argumentative debates in family (Arcidiacono & Bova, forthcoming). They also demonstrate the relevance of an accurate knowledge of the context in order to evaluate the argumentative dynamics of the family conversations at dinnertime (Arcidiacono et al., 2009).

For the above-mentioned reasons, family conversations are activity types in which parents and children are involved in different argumentative exchanges. By this study, I intend to focus on the implicitness and its functions within argumentative discussions in the family context, showing how it is a specific argumentative strategy adopted by parents during dinner conversations at home with their children. It is important to emphasize that argumentation constitutes an intrinsically context-dependent activity which does not exist unless it is embedded in specific domains of human social life. Argumentation cannot be reduced to a system of formal procedures as it only takes place embodied in actual communicative and non-communicative practices and spheres of interaction (van Eemeren et al., 2009; Rigotti & Rocci, 2006). Indeed, as van Eemeren & Grootendorst (2004) suggest, knowledge of the context is relevant in the reconstruction; and, more specifically, the so-called “third-order” conditions (ibid: 36-37), referring to the “‘external’ circumstances in which the argumentation takes place must be taken into account when evaluating the correspondence of argumentative reality to the model of a critical discussion. Thus, in analyzing family conversations, the knowledge of the context has to be integrated into the argumentative structure itself in order to properly understand the argumentative moves adopted by family members. Accordingly, the apparently irregular, illogical and incoherent structures emerging in these natural discourse situations (Brumark, 2006a) require a “normative” model of analysis as well as specific “empathy” towards the subject of the research, as both elements are necessary to properly analyze the argumentative moves which occur in the family context.

3. Data and method

The present study is part of a larger project[ii] devoted to the study of argumentation within the family context. The general aim of the research is to verify the impact of argumentative strategies for conflict prevention and resolution within the dynamics of family educational interactions. The data corpus includes video-recordings of thirty dinners held by five Italian families and five Swiss families. All participants are Italian-speaking.

In order to minimize the researchers’ interferences, the recordings were performed by families on their own[iii]. Researchers met the families in a preliminary phase, to inform participants about the general goals of the research, the procedures, and to get the informed consent. Further, family members were informed that we are interested in “ordinary family interactions” and they were asked to try to behave “as usual” at dinnertime. During the first visit, a researcher was in charge of placing the camera and instructing the parents on the use of the technology (such as the position and the direction of the camera, and other technical aspects). Families were asked to record their interactions when all family members were present. Each family videotaped their dinners four times, over a four-week period. The length of the recordings varies from 20 to 40 minutes. In order to allow the participants to familiarize themselves with the camera, the first recording was not used for the aims of the research. In a first phase, all dinnertime conversations were fully transcribed[iv] using the CHILDES system (MacWhinney, 1989), and revised by two researchers until a high level of consent (80%) was reached.

After this phase, the researchers jointly reviewed with family members all the transcriptions at their home. Through this procedure, it has been possible to ask family members to clarify some unclear passages (in the eyes of the researchers), i.e. allusions to events known by family members but unknown to others, low level of recordings, and unclear words and claims.

3.1 The model of Critical Discussion

In order to analyze the argumentative sequences occurring in family, we are referring to the model of Critical Discussion (hereafter CD) developed by van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1984, 2004). This model is a theoretical device developed within the pragma-dialectics to define a procedure for testing standpoints critically in the light of commitments assumed in the empirical reality of argumentative discourses. The model of CD provides a description of what argumentative discourse would be as if it were optimally and solely aimed at resolving a difference of opinion about the soundness of a standpoint[v]. It is relevant to underline that CD constitutes a theoretically based model to solve differences of opinion, which does not refer to any empirical phenomena. Indeed, as suggested by van Eemeren (2010), “in argumentative reality no tokens of a critical discussion can be found” (p. 128).

The model of CD consists of four stages that discussants should go through, albeit not necessarily explicitly, in the attempt to solve a disagreement. In the initial confrontation stage the protagonist advances his standpoint and meets with the antagonist’s doubts, sometimes implicitly assumed. Before the argumentation stage, in which arguments are put forth for supporting/destroying the standpoint, parties have to agree on some starting point. This phase (the opening stage) is essential to the development of the discussion because only if a certain common ground exists, it is possible for parties to reasonably resolve – in the concluding stage – the difference of opinions[vi].

In order to fully understand the logics of the model, it is necessary to refer to what van Eemeren and Houtlosser (2002) have developed as the notion of strategic maneuvering. It allows reconciling “a long-standing gap between the dialectical and the rhetorical approach to argumentation” (p. 27), and takes into account the arguers’ personal motivations for engaging in a critical discussion. In fact, in empirical reality discussants do not just aim to perform speech acts that will be considered reasonable by their fellow discussants (dialectical aim), but they also direct their contributions towards gaining success, that is to achieve the perlocutionary effect of acceptance (rhetorical aim).

In the present study, the model is assumed as a general framework for the analysis of argumentative strategies in family conversations. It is intended as a grid for the investigation, having both a heuristic and a critical function. In fact, the model can help in identifying argumentative moves as well as in evaluating their contribution to the resolution of the difference of opinion.

3.2 Specific criteria of analysis

According to the model of CD and in order to get an analytic overview of some aspects of discourse that are crucial for the examination and the evaluation of the argumentative sequences occurring in ordinary conversations, the following components must be elicited: The difference of opinion at issue in the confrontation stage; the premises agreed upon in the opening stage that serves as the point of departure of the discussion; the arguments and criticisms that are – explicitly or implicitly – advanced in the argumentation stage, and the outcome of the discussion that is achieved in the concluding stage. Besides, once the main difference of opinion is identified, its type can also be categorized (van Eemeren & Grotendoorst, 1992). In a single dispute, only one proposition is at issue, whereas in a multiple dispute, two or more propositions are questioned. In a nonmixed dispute only one standpoint with respect to a proposition is questioned, whereas in a mixed dispute two opposite standpoints regarding the same proposition are questioned.

4. Dinnertime conversations: A qualitative analysis

In this section I will present a qualitative analysis carried out on transcripts. In this work, I have identified the participants’ interventions within the selected sequences and I have examined the relevant (informative) passages by going back to the video data, in order to reach a high level of consent among researchers. Finally, I have built a collection of instances, similar in terms of criteria of the selection, in order to start the detailed analysis of argumentative moves during family interactions. As each family can be considered a “case study”, I am not interested here in doing comparisons among families. For this reason, and in order to make clear and easy the presentation of the excerpts, the cases below present situations considered and framed in their contexts of production, accounting for certain types of argumentative moves.

4.1 Analysis

In order to analyze the functions of implicitness within family argumentations, I am presenting two excerpts as representative case studies of argumentative sequences among parents and children, in which parents make use of sentences with a high degree of implicitness, with the goal of verifying to what extent implicitness can be considered a specific argumentative strategy adopted by parents during dinner conversations with their children in order to achieve their goal. I have applied the above-mentioned criteria of analysis in order to highlight the argumentative moves of participants during the selected dinnertime conversations.

The first example concerns a Swiss family (case 1) and the second is related to an Italian family (case 2). In the excerpts, fictitious names replace real names in order to ensure anonymity.

4.2 Case 1: “The noise of crisp bread”

Participants: MOM (mother, age: 35); DAD (father, age: 37); MAR (child 1, Marco, age: 9); FRA (child 2, Francesco, age: 6).

All family members are seated at the table waiting for dinner.

1 *FRA: mom. [=! a low tone of voice]

2 *MOM: eh.

3 *FRA: I want to talk:: [=! a low tone of voice]

→ *FRA: but it is not possible [=! a low tone of voice]

→ *FRA: because <my voice is bad> [=! a low tone of voice]

4 *MOM: absolutel not

→ MOM: no::.

5 *FRA: please:: mom:

6 *MOM: why?

7 *FRA: [=! nods]

8 *MOM: I do not think so.

→ *MOM: it’s a beautiful voice like a man.

→ *MOM: big, beautiful::.

9 *FRA: no.

%pau: common 2.5

10 *MOM: tonight: if we hear the sound of crisp bread ((the noise when crisp bread is being chewed)) [=! smiling]

11 *FRA: well bu [:], but not::: to this point.

%pau: common 4.0

The sequence starts with the intervention of the child (turn 1, “mom”) that selects the addressee (the mother), with a low tone of voice as sign of hesitation. After a sign of attention by the mother (turn 2, “eh”), Francesco makes explicit his request “turn 3, (“I want to talk”) and the problem that is at stake. When he explains the reason behind his opinion, the mother expresses her disagreement and tries to moderate her intervention through repetition of the genitive mark and the prolonging of the sound (turn 4, “absolutely not, no::”). At this point, the discussion is at the phase of the confrontation stage. In fact, it becomes clear that there is a child’s standpoint (my voice is bad) that meets the mother’s contradiction. In particular, in turn 5 Francesco does not provide further arguments to defend his position. In fact, for him, it is so evident that his voice is bad and he tries to convince the mother to align to this position through a recontextualization (Ochs, 1992) of the claim (“please:: mom:”). The prolonging of the sound is thus a way to recall the mother’s attention to the topic of discussion (and the different positions about the topic). In turn 6 the mother asks the child the reason behind such an idea (“why?”), expressing her need for explanation and clarification. From an argumentative point of view, the sequence turns to a very interesting point. In fact, Francesco does not provide further arguments to defend his position, but he answers with a non-verbal act which aimed at confirming his position (he nods as to say that it is self-evident). Despite the mother’s request, it is clear that the child evades the burden of proof. At this point the mother states that she completely disagrees with her child (turn 8, “I do not think so”), and by assuming the burden of proof she now accepts to be the protagonist of the discussion. Indeed, she provides arguments in order to defend her standpoint (your voice is not bad), telling her child that his voice is beautiful as that of a grown-up man.

At this point, the mother uses an ironic expression, an argument with a high degree of implicitness (turn 10, “tonight if we hear the sound of crisp bread”). Indeed, she tells the child that if that evening, strange noises were heard, such as that of crisp bread being chewed, it would be her child’s voice. It is interesting to notice that the mother uses the first person plural (“we hear the sound”) in order to signal a position that puts the child versus the other family members. The presumed alliance among family members reinforces the idea that the claim of Francesco is not supported by the other participants. The use of epistemic and affective stances (turn 8, “a beautiful voice…big, beautiful”) and the irony (turn 10) emphasize the value of the indexical properties of speech through which particular stances and acts constitute a context.

In pragma-dialectical terms, from turn 5 to turn 10, the mother and the child go through an argumentation stage. In turn 11 Francesco maintains his standpoint but he decreases its strength in a way (“well but not to this point”). Indeed, we could paraphrase Francesco’s answer as follows: Yes, I have a bad voice, but not so much! Not to that point, not as strange as the noise of crisp bread being chewed! The child’s intervention in turn 11 is an opportunity to re-open the conversation about the voice, in particular if we consider the beginning of the claim (“well”) as a proper key site (Vicher & Sankoff, 1989) to potentially continue the argumentative activity. However, the common pause of 4 seconds closes the sequence and marks the concluding stage of the interactions.

In argumentative terms, we could reconstruct the difference of opinion between the child and his mother as follows:

Issue: How is Francesco’s voice?

Protagonist: both mother and child

Antagonist: both mother and child

Type of difference of opinion: single-mixed

Mother’s Standpoint: (1.) Francesco’s voice is beautiful

Mother’s Argument: (1.1) It is big, like a grown-up man

Child’s Standpoint: (1.) My voice is bad

Child’s Argument: (1.1.) (non-verbal act: he nods as to say that it is self-evident)

4.3 Case 2: “Mom needs the lemons”

Participants: MOM (mother, age: 32); DAD (father, age: 34); GIO (child1, Giovanni, age: 10); LEO (child2, Leonardo, age: 8); VAL (child3, Valentina, age: 5).

All the family members are eating, seated at the table.

1 *LEO: Mom:: look!

→ *LEO: look what I’m doing with the lemon.

→ *LEO: I’m rubbing it out.

→ *LEO: I’m rubbing it out!

→ *LEO: I’m rubbing out this color.

%sit: MOM takes some lemons and stoops down in front of LEO so that her face is level with his.

%sit: MOM places some lemons on the table.

2 *LEO: give them to me.

3 *MOM: eh?

4 *LEO: can I have this lemon?

5 *MOM: no:: no:: no:: no::

6 *LEO: why not?

7 *MOM: why not?: because, Leonardo, mom needs the lemons

8 *LEO: why mom?

9 *MOM: because, Leonardo, your dad wants to eat a good salad today

10 *LEO: ah:: ok mom

During dinner, there is a difference of opinion between Leonardo and his mother. Leonardo, in fact, wants to have the lemons, that are placed on the table, to play with (turn 2), but the mother says that he cannot have them (turn 5).

5 *MOM: no:: no:: no:: no::

The mother’s answer is clear and explicit: she does not want to give the lemons to her child. The discussion is at the phase of the confrontation stage. In fact, it becomes clear that there is a child’s standpoint (I want the lemons) that meets the mother’s contradiction.

At this point Leonardo (turn 6) asks his mother why he cannot have the lemons. The mother answers (turn 7) that she needs the lemons. But as we can note from the Leonardo’s answer in turn 8, this argument is not sufficient to convince him to change his opinion. In fact, he continues to ask his mother:

6 *LEO: why not?

7 *MOM: why not?: because, Leonardo, mom needs the lemons

8 *LEO: why mom?

At this point, the mother uses an expression with a high degree of implicitness:

9 *MOM: because, Leonardo, your dad wants to eat a good salad today

Indeed, she tells the child that his dad wants to eat a good salad, and that in order to prepare a good salad she needs the lemons. In pragma-dialectical terms, from turn 6 to turn 9, the mother and the child go through an argumentation stage. In turn 10 Leonardo accepts the argument put forward by the mother and, accordingly, marks the concluding stage of this interaction.

In argumentative terms, we could reconstruct the difference of opinion between the child and his mother as follows:

Issue: Can Leonardo have the lemons?

Protagonist: both mother and child

Antagonist: both mother and child

Type of difference of opinion: single-mixed

Mother’s Standpoint: (1.) You can’t have the lemons

Mother’s Argument: (1.1) mom needs the lemons

Mother’s Argument (1.2) dad wants to eat a good salad today

Child’s Standpoint: (1.) I want the lemons

5. Discussion

In both sequences parents make use of the implicitness during conversations at home with their children in order to achieve their goal. In the first excerpt, the mother puts forward an argument with implicit meaning in order to persuade her child to retract his standpoint. In turn 10, by saying:

10 *MOM: tonight [:] if we hear the sound of “bread schioccarello” ((the noise when crisp bread being chewed)) [=! smiling] [=! ironically]

she is telling the child that if that evening all family members (‘we hear’) heard strange noises, such as that of crisp bread being chewed, it would be the child’s voice. In my opinion, the child’s answer makes it clear that he understood the implicit meaning of the mother’s argument. Indeed, Francesco maintains his standpoint, but in a certain way, he decrease its strength.

11 *FR1: well bu [:] but not:: to this point.

We can paraphrase Francesco’s answer as follow: “Yes, I have a bad voice, but not so much! Not to that point, not as strange as the noise of crisp bread being chewed!”.

According to leading scholars, commenting ironically on the attitudes or habits of children, appears to be a socializing function adopted by parents in the context of family discourse (Rundquist 1992; Brumark 2006b). In the first excerpt, commenting ironically Francesco’s standpoint by means of an argument with a high degree of implicitness, could be also interpreted as the specific form of strategic maneuvering adopted by the mother with her child in order achieve her goal. Furthermore, it is important to stress that a necessary condition for the effectiveness of this form of strategic maneuvering is that the implicit meaning is clear and shared by both arguers (i.e. Francesco understands the implicit meaning of the mother’s utterance).

In the first case, we saw how the mother can use an argument with implicit meaning in order to persuade her child to retract his standpoint. On the other hand, in the second excerpt, the mother tries to convince her child to accept her standpoint. Indeed, in turn 9 she says:

9 *MOM: because, Leonardo, your dad wants to eat a good salad today

In this case it is clear and explicit that the mother refers to father’s anger and authority, and she does so implicitly. Besides, by anticipating the possible consequences of his behavior, the mother is implicitly telling the child that the father might be displeased by the person who was the cause of him not having a good salad. Now, the mother’s behavior could be interpreted as the specific form of strategic maneuvering adopted with her child in order achieve her goal.

Furthermore, as suggested by Caffi (2007), using an argument with a high degree of implicitness can “mitigate” the direction of an order. Accordingly, the order is presented in a less direct way, we could say “more gentle”, and so the child perceives it not as an imposition. For instance, saying that the child cannot have the lemons because dad wants to eat a good salad, can appear in the child’s eyes as a desire that has to be carried out, and not an order without any justification.

6. Conclusion

In this paper I have tried to show how implicitness can be considered a specific argumentative strategy adopted by parents during dinner conversations with their children in order to achieve their goals. At this point it seems appropriate to take stock of the acquisitions of the ongoing research presented here, listing also the approximately drawn solutions that need to be specified.

Firstly, implicitness appears to be a specific argumentative strategy used by parents in family conversations with their children. Indeed, implicitness in the cases analyzed has two specific functions: In the first case, implicitness is a specific form of strategic maneuvering adopted by the mother to persuade her child to retract or reduce the strength of his standpoint. In the second case, anticipating the possible consequences of his behavior, by means of an argument with a high degree of implicitness, is another form of strategic maneuvering adopted by the mother in order to persuade her child to accept her standpoint.

Secondly, considering the two cases analyzed, we have seen that in order to be an effective argumentative strategy, implicitness has to be clear and understood by both parties. Lastly, parents seem to make use of the implicitness to put forward their arguments in a less directive form. In other words, by means of implicitness parents mitigate the direction of an order.

Considering the two cases as part of a larger research project, some questions about the argumentative moves of family members at dinnertime still remain unanswered. In particular, to provide further analyses of the collected data, we need to understand to what extent family argumentation corresponds to a reasonable resolution of the difference of opinion, to highlight the specific nature of argumentative strategies used by family members and to construct a typology of the several functions of the implicitness in the argumentative exchanges between family members, defining whether it is possible to consider young children as reasonable arguers, by taking into consideration their communicative and cognitive skills.

Appendix: Transcription conventions

. falling intonation

? rising intonation

! exclaiming intonation

, continuing intonation

: prolonging of sounds

[ simultaneous or overlapping speech

(.) pause (2/10 second or less)

( ) non-transcribing segment of talk

(( )) segments added by the transcribers in order to clarify some elements of the discourse

NOTES

[i] The notion of activity type has been developed by Levinson (1979), in order to refer to a fuzzy category whose focal-members are goal-defined, socially constituted with constraint on participants, settings and other kinds of allowable contributions. According to van Eemeren (2010), communicative activity types are conventionalized practices whose conventionalization serves, through the implementation of certain “genres” of communicative activity, the institutional needs prevailing in a certain domain of a communicative activity. Within this framework, family dinner is a specific communicative activity type within the domain of communicative activity named interpersonal communication. In their model of communication context, Rigotti and Rocci (2006) characterize the activity type as the institutional dimension of any communicative interaction – interaction schemes – embodied within an interaction field.

[ii] I am referring to the Research Module “Argumentation as a reasonable alternative to conflict in family context” (project n. PDFMP1-123093/1) founded by Swiss National Science Foundation. It is part of the ProDoc project “Argupolis: Argumentation Practices in Context”, jointly designed and developed by scholars of the Universities of Lugano, Neuchâtel, Lausanne (Switzerland) and Amsterdam (The Netherlands).

[iii] From a deontological point of view, recordings made without the speakers’ consent are unacceptable. It is hard to assess to what extent informants are inhibited by the presence of the camera. However, I tried to use a data gathering procedure that minimizes this factor as much as possible. For a more detailed discussion, cf. Arcidiacono & Pontecorvo (2004)..

[iv] For the transcription symbols, see the Appendix.

[v] Standpoint is the analytical term used to indicate the position taken by a party in a discussion on an issue. As Rigotti and Greco Morasso (2009) put it: “a standpoint is a statement (simple or complex) for whose acceptance by the addressee the arguer intends to argue” (p. 44).

[vi] I agree with Vuchinich (1990) who points out that real-life argumentative discourse does not always lead to one “winner” and one “loser”. Indeed, frequently the parties do not automatically agree on the interpretation of outcomes. In this perspective, the normative model of critical discussion has to be systematically brought together with careful empirical description.

REFERENCES

Arcidiacono, F., & Bova, A. (in press). Argumentation among family members in Italy and Switzerland: A cross-cultural perspective. In Y. Kashima & S. Laham (Eds.), Cultural Change, Meeting the Challenge. Proceedings Paper. Melbourne: IACCP.

Arcidiacono F., & Bova, A. (forthcoming). “I want to talk but it’s not possible!” Dinnertime Argumentation in Italian and Swiss families. Journal of US-China Education Review.

Arcidiacono, F., & Pontecorvo, C. (2004). Più metodi per la pluridimensionalità della vita familiare. Ricerche di Psicologia, 27(3), 103-118.

Arcidiacono, F., Pontecorvo, C. & Greco Morasso, S. (2009). Family conversations: the relevance of context in evaluating argumentation. Studies in Communication Sciences, 9(2), 79-92.

Blum-Kulka, S. (1997). Dinner Talk: Cultural Patterns of Sociable and Socialization in Family Discourse. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Brumark, Å. (2006a). Argumentation at the Swedish family dinner table. In F. H. van Eemeren, A. J. Blair, F. Snoeck-Henkemans & Ch. Willards (Eds.), Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 513-520). Amsterdam: Sic Sat.

Brumark, Å. (2006b). Non-observance of Gricean maxims in family dinner table conversation. Journal of Pragmatics, 38, 1206-1238.

Brumark, Å. (2008). “Eat your Hamburger!” – “No, I don’t Want to!” Argumentation and Argumentative Development in the Context of Dinner Conversation in Twenty Swedish Families. Argumentation, 22, 251-271.

Burger, M. & Guylaine, M. (2005). Argumentation et Communication dans les Medias. Quebec: Nota Bene.

Caffi, C. (2007). Mitigation. Studies in Pragmatics. Bd.4. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Cigada, S. (2008). Les Èmotions dans le Discours de la Construction Européenne. Milano: ISU.

Davidson, R. G., & Snow, C. E. (1996). Five-year-olds’ interactions with fathers versus mothers. First Language, 16, 223-242.

Eemeren, F.H. van (2010). Strategic Maneuvering in Argumentative Discourse. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Greco Morasso, S., Grossen, M., Perret-Clermont, A.-N., & Rigotti, E. (2009). Argupolis: a Doctoral Program on Argumentation practices in different communication contexts. Studies in Communication Sciences, 9(1), 289-301.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1984). Speech Acts in Argumentative Discussion: A Theoretical Model for Analysis of Discussions Directed Towards Solving Conflicts of Opinion. Dordrecht/Cinnaminson USA: Foris.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies: a Pragma-Dialectical Perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A Systematic Theory of Argumentation: The Pragma-Dialectical Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Houtlosser, P. (2002). Strategic maneuvering: Maintaining a delicate balance. In F.H. van Eemeren & P. Houtlosser, Dialectic and Rhetoric: The Warp and Woof of Argumentation Analysis (pp. 131-159). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Feteris, E.T. (1999). Fundamentals of Legal Argumentation: A Survey of Theories on the Justification of Judicial Decisions. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Feteris, E.T. (Ed.). (2005). Schemes and Structures of Legal Argumentation. Argumentation, 19(4) (special issue).

Greco Morasso, S. (in press). Argumentation in Dispute Mediation: a Reasonable Way to Handle Conflict. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Jacobs, S., & Aakhus, M. (2002). How to resolve a conflict: two models of dispute resolution. In F.H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Advances in Pragma-Dialectics (pp. 29-44). Newport News, VA: Sic Sat/Vale Press.

Levinson, S. C. (1979). Activity type and language. Linguistics, 17, 365-399.

MacWhinney, B. (1989). The Child Project: Computational Tools for Analyzing Talk. Pittsburgh: Mellon University Press.

Maynard, D.W. (1985). How children start arguments. Language in Society, 14, 1-29.

Mercer, N. (2000). Words and Minds: How We Use Language to Think Together. London: Routledge.

Muller-Mirza, N., & Perret-Clermont, A.-N. (Eds.). (2009). Argumentation and Education. New York: Springer.

Muller-Mirza, N., Perret-Clermont, A.-N., Tartas, V., & Iannaccone, A. (2009). Psychosocial processes in argumentation. In Muller-Mirza, N., & Perret-Clermont, A.-N. (Eds.), Argumentation and Education (pp. 67-90). New York: Springer.

Ochs, E. (1992). Indexing gender. In A. Duranti & C. Goodwin (Eds.), Rethinking context: language as an interactive phenomenon (pp. 335-358). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ochs, E., & Shohet, M. (2006). The cultural structuring of mealtime socialization. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 111, 35-49.

Pan, B.A., Perlmann, R. Y., & Snow, C. (2000). Food for thought: Dinner-table as a context for observing parent-child discourse. In L. Menn & N. Bernstein Ratner (Eds.), Methods for Studying Language Production (pp. 203-222). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Pontecorvo, C., & Arcidiacono, F. (2007). Famiglie all’Italiana. Parlare a Tavola. Milano: Raffaello Cortina Editore.

Pontecorvo, C., & Fasulo, A. (1997). Learning to argue in family dinner conversation: The reconstruction of past events. In L. Resnick, R. Säljö & C. Pontecorvo (Eds.), Discourse Tools and Reasoning (pp. 406-439). Berlin: Springer.

Pontecorvo, C., Fasulo, A., & Sterponi, L. (2001). Mutual apprentices: The making of parenthood and childhood in family dinner conversations. Human Development, 44, 340-361.

Rigotti, E., & Greco Morasso, S., (2009). Argumentation as an object of interest and as a social and cultural resource. In Muller-Mirza, N. & Perret-Clermont, A.-N. (Eds.), Argumentation and Education (pp. 9-66). New York: Springer.

Rigotti, E., & Rocci, A. (2006). Towards a definition of communication context. Foundations of an interdisciplinary approach to communication. Studies in Communication Sciences, 6(2), 155-180.

Rubinelli S., & Schulz P. (2006). Let me tell you why! When argumentation in doctor-patient interaction makes a difference. Argumentation, 20(3), 353-375.

Rundquist, S. (1992). Indirectness: a gender study of flouting Grice’s maxims. Journal of Pragmatics, 18, 431-449.

Schulz P., & Rubinelli S. (2008). Arguing ‘for’ the patient. Strategic maneuvering and institutional constraints in doctor-patient interaction. Argumentation, 22(3), 423-432.

Schwarz, B., Perret-Clermont, A.-N., Trognon, A., & Marro, P. (2008). Emergent learning in successive activities: learning in interaction in a laboratory context. Pragmatics and Cognition, 16(1), 57-91.

Walton, D. (2007). Media Argumentation: Dialectic, Persuasion and Rhetoric. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vicher, A., & Sankoff, D. (1989). The emergent syntax of presentential turn-openings. Journal of Pragmatics, 13, 81-97.

Vuchinich, S. (1990). The sequential organization of closing in verbal family conflict. In A. Grimshaw (Ed.), Conflict Talk (pp. 118-138). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zarefsky, D. (2009). Strategic maneuvering in political argumentation. In F. H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Examining Argumentation in Context: Fifteen Studies on Strategic Maneuvering (pp. 365-376). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.