ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Wellman And Govier On Weighing Considerations In Conductive Pro And Contra Arguments

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

The concept of conductive argument remains unsettled and controversial in theory of argument. Carl Wellman (1971, p. 52) defined conduction as follows:

Conduction can best be defined as that sort of reasoning in which 1) a reason about some individual case 2) is drawn non-conclusively 3) from one or more premises about the same case 4) without appeal to other cases.

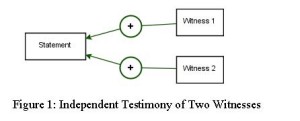

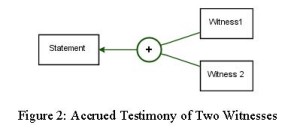

Wellman identified three types of conductive argument: Type One with a single pro reason, Type Two with multiple pro reasons, and Type Three with one or more pro reasons and one or more con reasons. Arguments of the conductive type are clearly non-deductive and, most theorists would argue, non-inductive as well. The term “conductive” indicates a ‘bringing together’ of independent reasons, much like an orchestra conductor brings together many instruments and musicians into a single performance.

The theoretical issues surrounding the concept of conductive argument are almost too numerous to even list in a paper focused on a particular issue. Are all conductive arguments case-based? Should we be talking of conductive evaluations rather than of arguments? Are deductive, inductive, and conductive argument (or evaluation) types an exhaustive and mutually exclusive list? If all conductive arguments are diagrammed as convergent, do we want to say that all convergent arguments are conductive? Even more fundamentally, why should we model various pro and con arguments on a single issue as one conductive argument? There are many other basic questions and issues that could be listed as well.

The focus of the present paper is on the concept of premise weight in Type Three conductive pro and con arguments. Some theorists want to restrict the concept of ‘conductive’ to Type Three pro and con arguments (or evaluations). The present paper tables that proposal and proceeds on a working hypothesis that understanding the more complex Type Three conductive arguments is a useful pathway for achieving a better understanding of the less complex Types One and Two.

2. Wellman’s ‘Heft’ and Premise Weight

Talk of ‘weighing’ reasons pro and contra is a common manner of speaking. “Premise weight” is an obviously metaphorical expression which some theorists view as an over-stretched and faulty metaphor with respect to its application in theory of argument. For example, Harald Wohlrapp wrote in his Der Begriff des Arguments (2008):

The upshot of the discussion of conductive argument is the following: The conclusion reached with arguments presented is not the result of a weighing, whatever that may be. (p. 333; trans. p. 21)

Trudy Govier is perhaps the only widely known theorist of argument who, in multiple publications, has endorsed and expanded upon Wellman’s concept of premise weight. For Govier, premise weight is not literally measurable, which implies that premise weight must be non-numerical in some sense.

It is important to note that “outweighing” is a metaphorical expression at this point. We cannot literally measure the strength of supporting reasons, the countervailing strength of opposing reasons, and subtract the one factor from the other. (1999, p. 171)

Carl Wellman, the originator of the concept of conductive argument, also seems to have understood premise weight to be non-numerical, as indicated in the following passage from his Challenge and Response (1971):

Nor should we think of the weighing [of reasons] as being done on a balance scale in which one pan is filled with the pros and the other with cons. This suggests too mechanical a process as well as the possibility of everyone reading off the same result in the same way. Rather one should think of weighing in terms of the model of determining the weight of objects by hefting them in one’s hands. This way of thinking about weighing brings out the comparative aspect and the conclusion that one is more than the other without suggesting any automatic procedure that would dispense with individual judgment or any introduction of units of weight. (1971, pp. 57-58)

In this passage, Wellman distinguishes two concepts of weight which might we might conveniently call scale-weight and heft-weight. Scale-weight involves machinery, even if only a simple balance type of scale. The output of the scale-weight process is numerical. Even on a simple balance scale, the use of standard weights can provide numerical weight outcomes. Scale-weight outcomes, being numerical, are precise and absolute rather than non-numerically comparative. Scale-weight is probably the current default meaning of “weight” in both theory of argument and in everyday contexts.

As Wellman, Govier and others have noted, scale-weight is not suitable as the literal basis for the premise weight metaphor. Per Wellman, heft-weight is the correct literal basis for this metaphor, and Govier would likely agree. To my knowledge, heft-weight has not received very much analytical attention in the literature on conductive argument, perhaps because heft-weight is viewed as uselessly vague and subjective. If this characterization is indeed suitable, then the concept of premise weight in theory of argument falls prey to a destructive dilemma. If scale-weight is the literal basis of the premise weight metaphor, then the metaphor is faulty and over-stretched. If heft-weight is the literal basis of the metaphor, then the metaphor is suitable, but premise weight is thereby uselessly vague and subjective. Perhaps the only way to save the concept of premise weight is to further recharacterize heft-weight. But what would that be like?

In contemplating heft-weight, we can imagine a person lifting several items one at a time and making a verbal pronouncement on each one. Initially the pronouncements will be comparative in nature, such as: much heavier than, heavier than, same weight as, lighter than, or much lighter than. A set of comparative, ranked weight categories is thus progressively created. The objects ranked by comparative weight could then be divided into perhaps five or so categories of non-numerical, verbal weight quantities such as: very heavy, heavy, medium, light, and very light. We need not think of the objects as individually ranked within each weight category, however. The individual human being is here functioning as a comparative weighing machine. Due to the lack of precision of heft-weight, there would be blurred boundaries between categories, and some items would have disputable weight categories, even with just one individual doing the hefting.

The outcome of this individual weighing process is a series of judgments that is objective in the sense that the human body is typically a good, if only approximate, weighing machine that provides a non-numerical, comparative, quantitative output. If one object had a lot more heft than another but a mechanical scale reported the reverse, we would properly believe we had a broken scale. This individual judgment of heft-weight is thus not subjective in the sense of individual personal preferences such as ‘chocolate tastes much better than vanilla’. But is heft-weight valid only for each individual weigher and thus non-objective in the sense of not intersubjective?

It seems to me that heft-weight should be understood as potentially intersubjective and thus objective, despite being non-numerical. As Aristotle noted, the solitary human being is either a beast or a God; so the standard case of Wellman’s ‘hefting’ individual is that he is a member of a group. Let’s say this group has about forty or so people, like the pre-Neolithic human bands, and that there is a mixture of the young and the old, and the frail and the robust. While Wellman’s individual lifter is doing his or her thing, the others are also picking up the same objects in the same way and classifying them into ranked weight categories.

It would soon be found that the mid-range of people in terms of physical ability generally find a group of objects heavy and another group of objects light in weight, approximately speaking. These objects would then become intersubjectively heavy, light, etc. The fact that the Milo’s of this group, the athletically trained weight lifters, found most of the common objects to be light in weight, and the small or frail of the group found most objects to be heavy would all be understood and adjusted for by members of the little group in the usual way. In effect, the mid-range of human strength becomes a kind of standard, much as color words are defined in the standard context of normal daylight. We do not think that red things turn black on a dark night, and we do not think that heavy things literally become light in Milo’s hands.

According to the above account, heft-weight, properly understood is non-numerical, approximate, comparative, and objective (intersubjective). On this characterization, heft-weight has many of the virtues of scale-weight, the major exceptions being lack of numerical output and consequent precision. Instead of numerical output, heft-weight provides non-numerical, comparative quantity categories of an approximate nature. Understood in this way, heft-weight is a very plausible literal basis for the metaphor of premise weight.

It might be objected that approximate, non-numerical quantities are not really quantities at all because quantities are by definition expressed as symbolic numbers. Although such a stance may have numerous defenders, the science of cognitive psychology has recently produced some interesting, and I think relevant, findings about what has been called the approximate number sense. Perhaps the term “quantitative capacity” would have been a better choice here than “number sense”, but the latter wording has taken hold. The distinction between two different quantitative ‘senses’ is more than just a conceptual one. While the symbolic number sense is processed in a spread-out fashion in the prefrontal cortex, the approximate number sense is embodied in another part of the brain called the intraparietal sulcus (Cantlon, et al, 2009) The two number senses seem to be connected in interesting ways. Current research provides preliminary indications that math education can benefit by co-developing the approximate sense and the symbolic number sense. (Halberda et al, 2008) Professional mathematicians are known to exercise their approximate number capacities when socializing at conferences. Classifying the approximate number sense as ‘mere intuition’ is likely an inappropriate over-simplification, given recent findings in cognitive psychology.

A commonly used example of the approximate number sense is when someone views several supermarket lines and classifies them as ‘shortest, short, medium, long, and longest’. Quantities are involved in this process, but typically no counting or symbols. Interestingly, other higher animals have this same ability, which provides obvious evolutionary advantages. The predator needs to choose which group of fleeing herbivores to chase; the fruit-eating animals need to pick which tree will provide the most fruit at the time. It seems quite plausible that this approximate number sense is involved in the process that produces heft-weight. The approximate number sense is comparative, non-numerical, and the product of individual judgment; and heft-weight is all of these things.

Unlike the other higher animals, humans in the process of discriminating quantities obviously verbally characterize the discriminated categories with comparative terms such as ’much more, more, about the same, less, and much less.’ In fact, we do this for a great many types of categories. A very common number of categories in such quantitative verbal hierarchies is three to five to perhaps seven. Seven items apparently are a common maximum quantity for simultaneous cognitive focus in humans. Examples of such additional categories include ‘rich/middle class/poor’, or super rich/rich/upper-middle-class/lower-middle-class/poor’ – and so on. In premise strength, we have ‘strong/moderate/weak’, or perhaps ‘very strong/strong/moderate/weak/very weak’, as categories of discriminated support quantities. Non-numerical quantity categories seem to be essential in human cognition and communication.

In correspondence, Trudy Govier has remarked to me that if the judgment is made to not use “weight” in theory of argument, then “one would have to figure out some other way of speaking. One might speak of deliberating, or comparatively considering, or making judgments of comparative significance.” (1/31/10) I think, and Govier might agree, that these potential substitutions for talk of premise weight would do less work overall than the premise weight concept, understood as heft-weight. We use comparative, non-numerical quantity categories in our reasoning all the time; so dismissing such reasoning as inherently faulty requires a high burden of proof which has not been met.

Non-numerical, comparative quantitative categories are frequently applied by speaking of degrees of this and that. For example, there are degrees of argument strength, degrees of importance, and so on in a great many areas of discourse. In her (2009), Govier has herself puzzled over the so-called ‘degrees’ of argument strength: “What are these degrees anyway? There is no answer.” It seems to me that the principal point of confusion here has to do with “degrees” bringing in symbolic numbers – or not.

Of course, some decision theorists do apply numbers to verbal premise weight categories, e.g. “5” for “very strong”, etc. This approach in my view is best regarded as a ‘game technology’; there are some useful applications for it in contexts of decision making. This ‘invented’ numerical premise weight has no rational basis for conductive argument evaluation for at least one major reason: The exact selection of the number scheme can actually determine the evaluation for some arguments.

To provide just one example, choosing a number scheme of 3-2-1 vs. one of 10-5-2 for the three ‘strong/medium/weak’ verbal categories determines the evaluation of an argument with the following premise weight classifications: four strong pro reasons, five moderate contra reasons, and five weak contra reasons. This type of argument supports its conclusion on a 3-2-1 assignment but not on a 10-5-2 assignment. There is seemingly no way to argue for the rational basis of one number scheme over another for labeling the commonly used verbal categories. Even the total number of quantitative categories is largely contextually determined rather than rule-based. For various reasons, applying numbers to verbal categories has limited theoretical use, if any.

If premise weight determination does not normatively involve the application of symbolic numbers, what positive account of premise weight emerges from the above account? I would argue that premise weight determination involves a classification of each individual premise into one of a small number of non-numerical quantitative categories. With the literal basis of Wellman’s premise weight metaphor, the verbal quantitative categories could be named: ‘very heavy’, ‘somewhat heavy’, ‘medium’, ‘light’ and ‘very light; the corresponding theory of argument categories would be similarly ‘very strong’, ‘somewhat strong’, ‘medium strength’, ‘’somewhat weak’, and ‘very weak.

These non-numerical, quantitative categories of premise weight categories are, to be sure, highly familiar ones. The intent of the above account is to provide them with a clearer grounding than they have previously received, to my knowledge. The fact that the exact names and even total number of such categories is variable and contextually determined is not in my view problematic.

The presumptive weight of an individual premise would in context be based on background knowledge and social values of the individuals and groups involved in argumentation. If a given premise weight is not agreed to, then it can argued for using some version of the scheme for argument to a classification. Premise weights can thus be seen as intersubjectively determinable, contextually and within limits. The contextual reality of deep disagreements is not an effective objection to premise weight as a key term in theory of argument, contrary for instance to Harald Wohlrapp’s critique of Govier on conductive argument.

We shall now apply the above account to some of Govier’s critics on the concept of premise weight and conductive argument, particularly those criticisms focused on quantitative issues. The interpretation of Govier is my own and is of course quite arguable; hopefully it has some measure of accuracy and value.

3. Govier’s ‘Exceptions’ and Issues of Quantification

Govier’s detailed account of weighing reasons is put forward in Chapter 10 of her Philosophy of Argument (1999) and in Chapter 12 of her textbook, A Practical Study of Argument, the current edition being the 7th (2010). In the first paragraph of her text’s section on conductive argument evaluation, she writes of premises’ “significance or weight for supporting the conclusion.” (p. 359) She soon introduces the specifics of her concept of premise weight, as follows:

While acknowledging that we are dealing here with judgment rather than demonstration, we will suggest a strategy for evaluating reasons put forward in conductive arguments. The premises state reasons put forward as separately relevant to the conclusion, and reasons have an element of generality. That generality provides opportunities for some degree of detachment in assessing the conclusion. Since this is the case, we can reflect on further cases when seeking to evaluate the argument. (2010, p. 361)

Govier’s explication of premise weight uses as its principal example an argument for the legalization of voluntary euthanasia; several of her major critics, including Harald Wohlrapp, have responded to her with further analyses of the same argument, so it is worth stating completely here:

(1) Voluntary euthanasia, in which a terminally ill patient consciously chooses to die, should be made legal.

(2) Responsible adult people should be able to choose whether to live or die.

Also, (3) voluntary euthanasia would save many patients from unbearable pain.

(4) It would cut social costs.

(5) It would save relatives the agony of watching people they die an intolerable and undignified death.

Even though (6) there is some danger of abuse, and

despite the fact that (7) we do not know for certain that a cure for the patient’s disease will not be found,

(1) Voluntary euthanasia should be a legal option for the terminally ill patient.

Govier identifies the associated generalizations for the pro reasons as follows, each with its ceteris paribus clause:

2a. Other things being equal, if a practice consists of chosen actions, it should be legalized.

3a. Other things being equal, if a practice would save people from great pain, it should be legalized.

4a. Other things being equal, if a practice would cut social costs, it should be legalized.

5a. Other things being equal, if a practice would avoid suffering, it should be legalized.

Each generalization is seen to have exceptions, which are the subject matter of the ceteris paribus clause.

For example, you could imagine social practices that would deny medical treatment to medically handicapped children, abolish schools for the blind, or eliminate pension benefits for all citizens over eighty. Such practices would save money, so in that sense they would cut social costs. But few would want to support such actions. Other things are not equal in such cases; the human lives of other people who are aided are regarded as having dignity and value, and the aid

is seen as morally appropriate or required. (2010, p. 361)

The principle of cutting social costs has, in Govier’s terms, a wide range of exceptions.

Perhaps Govier’s most succinct statement about premise strength is in her (1999, p. 171):

A strong reason is one where the range of exceptions is narrow. A weak reason is one where the range of exceptions is large.

For Govier, and within the present paper, the following are treated as roughly synonymous expressions because all are quantitative in a similar way: premise significance, weight, strength, and force. At issue here is the quantitative force of reasons in the broadest sense, as least for Wellmanian ‘type 3’ conductive pros and cons arguments.

Harald Wohlrapp challenges and rejects Govier’s account of a quantifiable range of ceteris paribus exceptions:

But why should the argument be weaker, because the associated if-then sentence has ‘more exceptions’? Can I really compare the number of exceptions through enumeration? Must we not bear in mind that the general principles are situation-abstract and that, depending on how they are being situated, they can have arbitrarily many exceptions? Is there anything countable here? (2008, pp. 323-324; trans. p. 10)

I would like to address this important critique in two respects: (1) issues regarding the nature of these exceptions and in particular their quantifiability; and (2) the general role of the ‘normal situation’ and ceteris paribus in everyday argumentation vs. in scientific contexts. This second issue area will be addressed in Section III of the present paper. What sort of things are these so-called exceptions?

As quoted above, Govier states that the point of framing the generalization associated with a conductive argument consideration is to identify additional cases falling within that generalization. According to Govier, these cases are then to be reflected on in the appropriate process of evaluating premise weight in conductive arguments. Such cases would seemingly be of two kinds, (1) actual cases past or present, and (2) fictional a priori, ‘what if’ cases, including potential future cases. It seems to me that the quantity of exceptions concerns not the number of items on a list of exception categories, which can be almost arbitrarily long. Rather, the quantity of exceptions must involve cases, actual or a priori as described above.

An illuminating question to ask at this point may be as follows: How does Govier come to reasonably believe that there are a great many exceptions to the generalization of cutting social costs? She obviously knows this from her experience living in a wide, but imprecisely delineated, moral community that one might call the developed democracies. She learned about the social values and behavior that create this ‘wide range of exceptions’ by experiencing multiple cases of a normative nature. Two critical questions for Govier’s account are: (1) How and in one sense are such cases counted or numerically assessed, and (2) How and in what sense are such cases relevant to the concerns of normative logic?

Any individual’s knowledge of how many exceptions there are to the principle of reducing social costs is imprecise, which suggests the involvement of the approximate number capacity described above. Explicitly counting exceptions to the principle of reducing social costs is not commonly done. We simply do not go around stating, for example, that there were 794 exceptions to the principle of cutting social costs in the U.S. Congress from 2005 to 2009. Instead, we learn in living which types of cases are very common and which are rare in our moral, legal, and social communities. We do not have in mind the details of most cases and we do not typically count them. We know of a great many cases in which social costs are borne so that other objectives can be attained. We know of comparatively few cases in which unbearable human pain is knowingly tolerated in favor of controlling social costs. Comparative, non-numerical, and individual judgment is being exercised, and that judgment has some objective basis in the quantity of cases comprising the relevant evidence. We acquire knowledge of actual social values by experiencing a great many cases, both legal cases and cases the everyday sense or situations and decisions made. But how are these relevant cases evaluated and processed as evidence, and what concepts and issues within normative logic are involved?

A very fruitful distinction to employ here might be that between case-based legal argument, emphasized in common law-oriented legal cultures, and rule-based legal argument found in civil-law-oriented legal cultures. If I am correct in interpreting Govier’s exceptions-based understanding of conductive argument as a matter of supporting cases in the widest sense of “case”, then the legal model of processing cases, rules and social values may provide insight into the normative aspects of everyday conductive reasoning.

A particularly interesting account of case-based and value-based legal reasoning has been provided Trevor Bench-Capon and George Christie. A legal argument is a paradigm of an argued case. Of course legal arguments and reasoning have been foundational for normative logic since Toulmin. In comparing case-based common law legal argument with rule-based civil law legal argument, George Christie very effectively highlighted the distinctive role of cases in the former:

Under the approach to legal reasoning now to be described [case-based, common law], so-called rules or principles are merely rubrics that serve as the headings for classifying and grouping together the cases that constitute the body of the law in a case-law system. In such a system even statutes are no more than a set of cases, if any, that have construed the statute together with the set of what might be called the paradigm cases that are, in any point in time, believed to express the meaning of the statute. (2000, p. 147)

Arguing from a few precedent cases is of course a standard argument by analogy using the ‘argument from precedent’ scheme. But the picture becomes more complex, and more interesting, once social values are brought in, as theorized by Bench-Capon.

For Bench-Capon, a given case in law is appropriately decided within a key context of often many other cases, past, present and future:

A given case is decided in the context both of relevant past cases, which can supply precedents which will inform the decision, and in the context of future cases to which it will be relevant and possibly act as a precedent. A case is thus supposed to cohere with both past decisions and future decisions. This context is largely lost if we state the question as being whether one bundle of factors is more similar to the factors of a current case than another bundle, as in HYPO, or whether one rule is preferred to another, as in logical reconstructions of such systems. (2000, pp. 73-74)

The context of cases is key because, according to Bench-Capon, “we see a case-based argument as being a complete theory, intended to explain a set of past cases in a way which is helpful in the current case, and intended to be applicable to future cases also. The two goals are closely linked. Values form an important part of our theories and they play a crucial rule in the explanations provided by our theories.” (2000, p. 74)

Bench-Capon believes that “the ‘meaning’ of a case is often not apparent at the time the decision is made, and is often not fixed in terms of its impact on values and rules. Rather, the interpretation of the case evolves and depends in part on how the case is used in subsequent cases.” (2000, p. 74). Thus case-based argument in law it is commonly not about a small number or cases implying a value scheme but is rather about potentially many relevant cases that modify value schemes in ways not always understood until later interpretations. There is a ‘theory of cases’ that new cases are constantly modifying.

What is the theoretical relevance of these legal arguments, understood as above, to conductive argument evaluation? The factors of legal argument analysis seem to me to be fundamentally the same as the considerations of general pro and con conductive arguments concerned with evaluative issues:

“The picture we see is roughly as follows: factors provide a way of describing cases. A factor can be seen as grounding a defeasible rule. Preferences between factors are expressed in past decisions, which thus indicate priorities between these rules. From these priorities we can adduce certain preferences between values. Thus the body of case law as a whole can be seen as revealing an ordering on values.” (2000, p. 76)

And further:

“In regard to legal theories cases play a role which is similar to the role of observations in scientific theories: they have a positive acceptability value, which they transfer to the theories which succeed in explaining them, or which can include them in their explanatory arguments.” (2000, p. 76)

Cases both express and develop value schemes, which consist of both lists of values and their prioritization in contexts of conflict. Henry Prakken has endorsed this approach as well: “As Bench-Capon [2] observes, many cases are not decided on the basis of already known values and value orderings, but instead the values and their ordering are revealed by the decisions. Thus one of the skills in arguing for a decision in a new case is to provide a convincing explanation for the decisions in the precedents.” (Prakken, 2000, pp. 8-9)

It seems very plausible to me that these points are applicable well beyond legal argumentation. Perhaps weight in conductive arguments, at least those focused on evaluational issues, might best be understood on the model of the above approach to legal case-based arguments. Our daily experience and decisions, both collective and individual, form a kind of case history which both expresses and continually forms and re-forms our values. Philosophers in recent decades have tended to understand moral issues (and sometimes practical issues) in terms of rule-based models rather than in terms of case-based models, but this long-term emphasis may have been overdone. It seems to me quite plausible that the case-based reasoning model would readily apply to non-moral, evaluative, conductive reasoning as well.

The idea of value schemes evolving with case decisions is entirely consonant with Stephen Toulmin’s remarks in The Abuse of Casuistry: “Historically the moral understanding of peoples grows out of reflections on practical experience very like those that shape common law. Our present readings of past moral issues help us to resolve conflicts and ambiguities today”. (1988, p. 316) It seems to me that taking the case-based understanding of legal reasoning, together with modeling much everyday evaluative reasoning on legal argument interpreted as value-centric, is a very promising direction.

Perhaps a very broad characterization of the type of reasoning in question might be what Robert C. Pinto and others have called “support by logical analogy”. In his (2001, p. 123), Robert C. Pinto describes the method of logical analogy as “pre-eminently important.” Pinto further notes: “Though it [argument from logical analogy] is fairly widely recognized as a method for justifying negative evaluation of arguments and inference, in my view it can also provide grounds for positive evaluations as well.” Govier addresses refutation by logical analogy in her textbook’s chapter on analogical reasoning. I am not aware of her addressing support by logical analogy elsewhere. David Hitchcock has written a very interesting paper (1994) on conductive argument validity which utilizes, according to my understanding of it, refutation by logical analogy; I believe he does not address “premise weight” here specifically. The point I would like to add is that support by logical analogy would seemingly involve analogous cases that might be argumentatively addressed in the mass, rather than in the substantial detail of a standard two-case argument by analogy.

It might be objected that in focusing on Govier’s talk of further cases to reflect on, I am hopelessly blurring the distinction between conductive and analogical argument. The claim that premise weight is commonly supported by, broadly speaking, analogical types of arguments does not imply that conductive arguments are types of analogical arguments. The main argument, the first tier of reasons above the conclusion (the main conclusion being at the bottom of the argument diagram), may be convergent but have analogical subarguments either in the dialectical tier or in corresponding evaluation arguments. It is interesting to note that analogical and conductive arguments are typologically ‘cousins’ in a sense in that both are inherently comparative in nature.

Not all conductive arguments are about valuational matters. Some theorists’ efforts regarding the ‘quantity of evidence’ in conductive argument might best be seen as regarding conductive arguments with non-valuational conclusions rather than conductive arguments in general. For instance, in his Cognitive Carpentry, John L. Pollock proposed numerical quantitative assignments to premises for arguments that can be interpreted as statistical syllogisms. In his (2002), Alexander V. Tyaglo has applied probability theory to separate reasons in convergent arguments. The epistemic status of the probability numbers themselves makes this approach one of limited scope and value.

Ideas from Pollock and from Tyaglo may be applicable to predictive (or dispositional) conductive arguments that seem to be arguments from sign. An example of such an argument appears early in Govier’s textbook chapter on conductive argument: “She must be angry with John because she persistently refuses to talk to him and she goes out of her way to avoid him. Even though she used to be his best friend, and even though she still spends a lot of time with his mother, I think she is really annoyed with him right now.” (2010, p. 366) Whether it is useful to identify two (or more?), subtypes of conductive argument, the empirical and the valuational, is an interesting question worth pursuing. The argument of the present paper concerns principally ‘valuational’ conductive arguments.

4. Cumulating Independent Reason Strands

The above account characterizes premise weight determination as normatively involving a scheme of argument to classification among a small number of non-numerical but quantitatively ranked categories, i.e. ‘very strong’, ‘strong’, etc. This claim is of course not at all novel. The present intent is to provide additional conceptual support and clarity for the concept of degrees of premise weight and argument strength. What is excluded for those who accept the above account is the view that premise weight is either entirely subjective or entirely objective, as would be implied by accepting the scale-weight model of premise weight or by rejecting the concept of premise weight altogether. The above account thus supports a middle ground of intersubjectivity.

Most of the above account has to do with the concept of individual premise weights. But, how are the various reason strands of a given argument to be normatively ‘conducted’ together into an evaluation of their net collective support, or lack thereof, for an argument’s stated conclusion? More ‘dustbin empiricism” might be helpful here in order to better develop what Robert C. Pinto calls critical practice, an aspect of which would here be a checklist of questions as a guideline to good conductive argument evaluation.

It seems to me that, descriptively, people commonly begin a conductive argument evaluation by viewing the whole argument and classifying considerations as major or minor. Ben Franklin famously crossed out opposing, equally (heft-) weighted considerations. Descriptively, it seems to me that we seem to hold those considerations identified as “minor” in reserve, in case there is a perceived ‘tie’ between the major considerations on each side. Arguments with, for instance, two strong pro premises, one weak pro premise, and two strong con premises may just be unresolvable, unless more considerations can be added or individual premise evaluation differences resolved by the arguers. But such common-sense observations and guidelines hardly constitute an example of adequate theory of argument.

It may very well turn out that normative logic has rather little to offer in terms of addressing premise cumulation in conductive argument. Harald Wohlrapp famously argues exactly this point and offers his dialectical frame-integration account of resolution. But it seems to me that his approach rings true because it brings in values; a frame for Wohlrapp is a valuational perspective on a set of characterized (or recharacterized) facts. Addressing values directly is, as previously mentioned, also a feature of legal case-based, value-based reasoning. Values are commonly brought into contexts of everyday conductive argument as well.

5. Conclusion

A longer paper would have been able to further address a number of issues regarding premise weight. For example, the concept of ceteris paribus and the ‘normal situation’ highlighted in Govier’s account deserves more extensive treatment. Also deserving of attention is Frank Zenker’s interesting proposal that (1) deductive, inductive and conductive arguments all have premise weights, but that (2) the premise weights in deductive and inductive arguments are ‘equal’ and thus in a sense tacit. (Zenker, 2010) Perhaps the concept of premise weight could be useful in clarifying evaluation typologies along the following lines: (a) deductive evaluation is structural with equal-weight reasons; (b) inductive evaluation is additive (or cumulative) with equal-weight reasons; and (c) conductive evaluation is comparative with, unequal-weight reasons.

Overall, the logic of conductive argument remains somewhat obscure, but perhaps we are collectively making some small progress. A main take-away from the present paper, in my view, is that the concept of premise weight is a fruitful one that is entirely worthy of contemporary interest and further investigation in theory of argument.

REFERENCES

Bench-Capon, T., & Sartor, G. (2000). Using values and theories to resolve disagreement in law. In J. Breuker, R. Leenes & R. Windels (Eds.), Legal Knowledge and Information Systems. Jurix 2000: The Thirteenth Annual Conference (pp. 73-84). Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Bench-Capon, T. (2001) Review of: The Notion of an Ideal Audience in Legal Argument. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 9(1), 59-71.

Cantlon, J., Libertus, M., Pinel, P., Dehaene, S., Brannon, E., & Pelphrey, K. (2009). The neural development of an abstract concept of number. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 21(11), 2217-2229.

Christie, G. (2000) The Notion of an Ideal Audience in Legal Argument. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Govier, T. (1999). The Philosophy of Argument. Newport News, VA: Vale Press.

Govier, T. (2009). More on dichotomization: flip-flops of two mistakes. In J. Ritola, Ed., Argument Cultures: Proceedings of OSSA Conference 2009. CD-ROM, Windsor, ON. June 2009.

Govier, T. (2010). A Practical Study of Argument, 7th edition. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Halberda, J., Mazzocco, M., & Feigenson, L. (2008). Individual differences in non-verbal number acuity correlate with maths achievement. Nature 455, 2 October 2008, 665-668.

Hitchcock, D. (1994). Validity in conductive arguments. In R. Johnson & J. A. Blair (Eds.), New Essays in Informal Logic (Ch. 5, pp. 58-67). Newport News, VA: Vale Press.

Jonsen, A., & Toulmin, S. (1988). The Abuse of Casuistry. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kock, C. (2007). Is practical reasoning presumptive? Informal Logic, 27, 91-108.

Libertus, M., & Brannon, E. (2009). Behavioral and neural basis of number sense in infancy. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2009, 18(6), 346-351.

Pinto, R. (2001). Cognitive science and the future of rational criticism. In Argument, Inference, and Dialectic (Ch. 12, pp. 113-125). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Pinto, R. (2009). Argumentation and the force of reasons. In J. Ritola (Ed.),Argument Cultures: Proceedings of OSSA Conference 2009. CD-ROM, Windsor, ON. June 2009.

Pollock, J. (1995). Cognitive Carpentry. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Prakken, H. (2000) An exercise in formalizing teleological case-based reasoning. In J. Breuker, R. Leenes & R. Windels (Eds.), Legal Knowledge and Information Systems. Jurix 2000: The Thirteenth Annual Conference (pp. 49-57). Amsterdam: Ios Press.

Tyaglo, A. (2002). How to improve the convergent argument calculation. Informal Logic, 22(1], 61-71.

Wellman, C. (1971). Challenge and Response. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Wohlrapp, H. (1998). A new light on non-deductive argumentation. Argumentation, 12(3), 341-350.

Wohlrapp, H. (2008). The pro- and contra-discussion (A critique of Govier’s “conductive argument”). Translation by Frank Zenker of: Wohlrapp, H. (2008) Der Begriff des Arguments, Section 6.4. Wurzburg: Konigshausen und Neumann. Retrieved from www.frankzenker.de/academia.

Zenker, F. (2007). Complexity without insight: Ceteris paribus clauses in assessing conductive argumentation. In S. Jacobs (Ed.), Proceedings of the 2007 NCA/AFA Conference on Argumentation, Alta, Utah, 810-181.

Zenker, F. (2009). Ceteris paribus in conservative belief revision. On the role of minimal change in rational Theory Development (Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hamburg). Berlin: Peter Lang (ISBN 978-3-631-57283-2).

Zenker, F. (2010). Deduction, induction, conduction: An attempt at unifying natural language argument structure. In Proceedings of the 13th Biennial Argumentation Conference at Wake Forest University, March 2010.

Zimmer, C. (2009). The math instinct. Discover Magazine. November, 2009, p. 28.