Post-Apartheid South Africa And The Crisis Of Expectation – DPRN Four

The collapse of the apartheid state and the ushering in of democratic rule in 1994 represented a new beginning for the new South Africa and the Southern African region. There were widespread expectations and hopes that the elaboration of democratic institutions would also inaugurate policies that would progressively alleviate poverty and inequality.

Fourteen years into the momentous events that saw Nelson Mandela become the president of South Africa, critical questions are being asked about the country’s transition, especially about its performance in meeting the targets laid down in its own macro-economic programmes in terms of poverty and inequality, and the consequences of the fact that the expectations of South Africans have not been met.

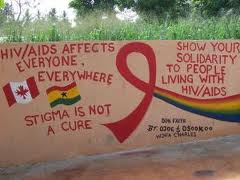

At a general level the euphoria of 1994 has come up against deepening inequality, rising unemployment, the HIV pandemic and bourgeoning violent crime. The latter has led one writer to conclude that South Africa is ‘a country at war with itself’ (Altbeker 2007).

South Africans have trusted democracy with the hard task to deliver jobs, wealth, healthcare, better housing and services to the people. But now that all of this is slow in arriving, there is growing disquiet and increased community protests that have sought to challenge the government on the pace of service delivery.

It is the level of what we have labelled a crisis of expectation that this paper speaks to. It looks at what under lies this crisis of expectation and what are the potential consequences.

The crisis of expectation and the political context

Whilst it can be said that under Mbeki’s leadership, efforts were made to develop and adopt some forward thinking policies and that his major contribution was his policy on modernizing the state, it can also be said that under his leadership several state institutions were set up to ensure good governance, the effectiveness of which is being contested at the moment. The relevance and the efficacy of these initiatives of the Mbeki government have taken precedence in the debate on the declining human development index in South Africa and in the run up to the ‘changing of the guard of the ruling party’.

Since the first democratic elections in 1994, the ANC has dominated the South African political scene and has shaped the way this country is today. The first term of ANC government was largely characterized by legislative developments with the purpose of creating a non-racial, non-sexist and democratic country. The government provided democratic policies and practices in order to ensure a checks-and-balances system of powers. This basically meant the independence of the judiciary, the promotion and protection of media freedom and the accountability of political institutions.

At the same time, during this decade of democracy, the ANC political leadership earned international recognition, and the reputation of being a good reconciler, mediator and peace-maker in relation to the political turmoil afflicting some African governments (DRC, Burundi and Zimbabwe). South Africa has taken the lead of African pan-unionism.The significance of its political leadership in the continent has been underlined by granting South Africa the chairpersonship of the African Union Commission on the occasion of the inauguration of the first session of the Pan-African Parliament, on 18 March 2004.

However, while the institutions of democracy have been elaborated and South Africa’s role in the continent enhanced, the challenge of economic upliftment of the poorest South Africans remains fundamental to the success of the transition.

This side of the mandate with which voters have trusted the ANC for three consecutive terms cannot be disputed. Since 1994, the ANC government has passed a significant amount of social legislation that claims to help address the inequities of the past. Starting from 1992-1993, spending on social services has grown from 44.4% of general government expenditure to 56.7% in 2002-2003. The government has facilitated the construction of 1.6 million new houses, supplied water to nine million households and sanitation to 6.4 million, and created two million net new jobs. Government also embarked on policies and programmes geared toward ensuring economic development.

The Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) and the Growth Employment and Redistribution Strategy (GEAR) sought to address the issue of economic development and sustainable growth. The efficacy of these programmes remains debatable. While on one hand the recent sound performance of South Africa’s macro-economy is attributed to the implementation of the fundamentals underlying GEAR, on the other hand GEAR has had negative consequences for the poor in South Africa.

This combination of social policies in some areas and of a conservative macroeconomic programme in others led to a sort of de-racialisation of the apex of the class structure but left the largest part of the population exactly where it was: marginalised, poor and overwhelmingly black.

Miceli ( 2007) is of the opinion that the fundamental challenge facing South Africa is the need to find sustainable means to overcome the apartheid legacy of racial division, poverty, and inequality; to reverse decades of distortionary political, social, and economic policies that disfavoured, rather than promoted, development. Seekings in 2000 argued in the same vein when he said that the end of apartheid may not have seen extensive racial desegregation, but it has seen the emergence of a clear class division in South African populace including the African populations. More importantly, the authors argue that if people have sufficient stake in their country, they will not destroy it and their fellow citizens.

The crisis of expectation and crime

The crisis of expectation and crime

Crime and violence have dominated South Africa’s transformation over the past two decades. High crime rates cause widespread feelings of insecurity and fear which undermine popular confidence in the democratisation process. Considering both trends and public perceptions, this paper explores changing crime levels over the past decade, elaborating on the problems associated with crime statistics in South Africa, and the salience of the transition for current crime levels. Data is drawn from official police statistics and from victimisation and other surveys. Crime has been increasing gradually in South Africa since 1980. It is, however, since 1990 – and not more recently, as popular belief has it – that levels have risen sharply. An examination of the statistics shows that despite general increases, not all crimes have been committed with equal frequency and not all areas of the country are similarly affected. These trends are a product of the political transition and are associated with the effects of apartheid and political violence, the breakdown in the criminal justice system and more recently, the growth in organised crime. High crime levels are taking their toll on South Africans. Surveys show that crime rather than socio-economic issues now dominates people’s concerns, and that fear of crime is increasing. Currently, fewer people feel safe and believe the government has the situation under control than in previous years. Faced with widespread unemployment on the one hand, and the prospects of development on the other, the levels of property crimes will probably continue to increase. While violent crime levels should decline over the medium term, improved relations with the police and a culture of reporting crimes like rape and assault may result in more crime being recorded.

The crisis of expectation and the declining human development trajectory

There is no doubt that the policies and RDP agenda of Government over the past 14 years have attempted to address the legacy of apartheid, but its implementation and the resultant outcomes were not ‘in sinc’ with these intentions. The declining Human development index is indicative of this reality.

According to Ul Haq, the objective of development is ‘to create an enabling environment for people to enjoy long, healthy and creative lives’.[i] In this regard, South Africa’s stated commitment in its constitution to the attainment of ‘a better life for all’, not just a better life for small pockets of this once-divided nation, should drive whatever we do to promote sustainable development. Mbeki in responding to the Human Development Report 2006 agreed that

… development and security complement mutually reinforce each other. It is clear that one simply cannot be achieved without the other, and neither is sustainable without respect for human rights, which empowers individuals and communities with the freedom to make better choices.

Yet, the statistics reflect otherwise.

In June 2006, the Presidency released its A nation in the making: A discussion document on macro-social trends in South Africa. The study found that between 1995 and 2000, the rural share of income poverty declined by approximately 5%, while it increased by 5% in the urban areas. In 1995, 28% of households lived below the estimated poverty datum line of R322 per month, while the figure for 2000 was just under 33%.

In terms of inequality, data shows that in 2000, the poorest 20% of households accounted for 2,8%. In contrast, the wealthiest 20% of households accounted for 64,5% of all expenditure. The income and expenditure Gini coefficients point to a rising inequality amongst Africans.

In terms of unemployment, the 2001 Labour Force Survey shows that that the distribution of those aged 15-65 by labour market status is as follows: 35,9% of Africans, 21,8% of Coloureds; 18,4% of Indians, and 6% of whites were unemployed. In September 2005, the figures were as follows: the unemployment rate amongst Blacks was 31,5%, 22,4% amongst Coloureds, and 5,1% amongst whites.

A further racial imbalance is that 50% of Africans live in households of four or more people, compared with 30% of whites. Yet, in terms of number of rooms available to households, 73% of Africans have four rooms or less to live in, including kitchens and toilets, while 86% of white households have four or more rooms in the household.

In terms of electricity, 40% of Africans use it as the energy source for cooking, while for whites this percentage is 96,6%. Of all the top management positions in the country, white males constitute 77,3%, compared to 5% Black males, 2% Coloured males, and 3.3% Indian males. For females, the percentages are 10,2% white females, 1,2% Blacks, 0,7% Coloureds, and 0,5% Indians.

Research shows that 51% of Black matriculates are still looking for employment, compared to 14% of Whites; 30% of Coloureds, and 28% of Indians. The less skilled are also caught in a poverty trap. As the Macro-social Report puts it: ‘The lack of knowledge is linked to social status’. In terms of gender, some 52,2% of the country’s population is female, but the male gender dominates political, economic and social life in the country.

Moving now to causes of death and social demographics, research shows that young Blacks and Coloureds are more likely to die of unnatural causes of death – mainly violence and car accidents – than other sections of the population. The macro-social report states that AIDS-related causes of death increased from about 15% of all deaths in 1997 to about 25% in 2001. It also states that ‘central in determining social behaviour is the system of ownership and distribution of resources, Coloured – in the South African setting – by race’.

The crisis of expectation and poverty

Poverty is inseparable from politics in South Africa, whether looking at origins and causes, its current form, or solutions. Since the turn of the century, a growing literature has sprung up attempting to answer the burning question of whether the South African income distribution has improved in terms of a reduction in poverty and inequality since political transition. In per capita terms South Africa is an upper-middle-income country, but notwithstanding this relative wealth, the experience of most South African households is one of absolute poverty or of continuing vulnerability to being poor. In addition, the distribution of income and wealth in South Africa is among the most unequal in the world, and many households still have unsatisfactory access to education, health care, energy and clean water. This triggered the famous quote in the 1998 parliamentary debate on reconciliation and nation-building, when then deputy president Thabo Mbeki (Mbeki 1998) famously argued that

Material conditions … have divided our country into two nations, the one black, and the other white. … [the latter] is relatively prosperous and has ready access to a developed economic, physical, educational, communication and other infrastructure … The second, and larger, nation of South Africa is black and poor, with the worst affected being women in the rural areas, the black rural population in general and the disabled.

This nation lives under conditions of a grossly underdeveloped economic, physical, educational, communication and other infrastructure. It has virtually no possibility to exercise what in reality amounts to a theoretical right to equal opportunity.

Measuring poverty is not a straightforward matter, as it depends on a critical assumption: what level of income constitutes the poverty line? Despite being considered an upper-middle income country, South Africa is a country of stark contrasts. The extreme inequality evident in South Africa means that one sees destitution, hunger and overcrowding side-by-side with affluence.

Poverty in South Africa has racial, gender and spatial dimensions, a direct result of the policies of the successive colonial, segregationist and apartheid regimes. Poverty is distributed unequally among the nine provinces. Provincial poverty rates are highest for the Eastern Cape (71%), Free State (63%), North-West (62%), Northern Province (59%) and Mpumalanga (57%), and lowest for Gauteng (17%) and the Western Cape (28%). Three children in five live in poor households, and many children are exposed to public and domestic violence, malnutrition, and inconsistent parenting and schooling. Redistribution of income in South Africa in order to address disparities is not a story of only the post-apartheid era. From the late 1970s, expenditure on Africans began to rise, first in response to increasing political instability from 1976, which led to rising education spending. Between 1990 and 1993, expenditure on Africans accelerated sharply as the apartheid government desperately tried to buy black support during the constitutional negotiations for the forthcoming universal franchise election (Gelb 2003: 11). In the post-apartheid era robust measures ranging from slowing down population growth in the black community to Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) have been initiated to address issues of poverty and inequality.

By the beginning of the new century the South African government had increased the social grants, which form the safety net for the poor, to 22 Billion Rand (Berg et al. 2006: 23). May (1998) points out that by early 1996 it had become clear that without new macroeconomic initiatives by the government, economic growth rates could not be attained that were both sustainable and high enough for effective poverty alleviation, income redistribution, employment creation and financing of essential social services. The government then formulated the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) strategy. GEAR reiterated government’s commitment to the existing economic policy framework, identified many of the structural weaknesses inhibiting economic growth and employment, and focused attention on market-based policies to address them. This helped to address employment creation, public works programmes, equity and discrimination, labour standards and job security, minimum wages and training for skilled labour. In order to address inequality in the health sector, the government also introduced universal access to primary health care in South Africa. In the Education sector the government gives leniency to Black South Africans’ access to tertiary education, allowing them to be enrolled despite having low academic grades.

Last but not least, the South African government needs to keep an eye on corruption which seems to be working against some of the initiatives like Black Economic Empowerment (BEE). Instead of tackling inequality, BEE has created a clique of very rich Black South Africans, thus causing more intra-racial inequalities.

The crisis of expectation and a de-racialised democracy

The radicalised and class-divided spaces created by the apartheid state did not automatically disappear after democratisation but have in fact become even further entrenched. The social structure of post-apartheid cities remains a neglected subject and in order to address some of the inequalities equitable allocation of housing should be made a priority. Government policies and the strategies of organised social actors with which these policies interact are fundamental, for they provide a framework through which change is enabled. It is the grinding together of different South Africans at grassroots levels, the white residents in the edges of the mountains in Cape Town, the black proletariat in the shacks in Khayelitsha and those eking a living at the edges, which will shape their common future (Dickinson 2002: 11). Some critics argue that this has become further entrenched by the very economic and developmental policies that were to prevent this from happening. Others still argue that these poverty-ravaged spaces have become fertile ground for crime and to some extent, pre-determine criminal behaviour amongst its residents. Government in its planning did not envisage the impact of the chain reaction that the instability in neighbouring states and the resultant migration of refugees would have on development in South Africa. The influx of refugees and migrants seeking a better life in South Africa resulted in heaping poverty on poverty, which has created a self-reinforcing cycle in which levels of crime within certain regions of the country have fostered a climate that favoured the current xenophobic behaviour of people within these areas.

The year 2009 is likely to see president Mbeki’s successor being confronted with the same harsh human development realities which confronted his predecessors Mandela and Mbeki. South Africa during the last ten years has dropped 35 places to being 120th on the UN’s global Human Development Index (HDI), mostly due to the AIDS pandemic.[ii] The main opposition however holds the government responsible for increasing ‘the gulf between the rich and poor’ to levels far higher than during apartheid through failed economic policies [iii].

Social policies and expenditure on people

Since 1994, there has been a qualitative shift in how government addresses the problems of poverty. In aid-dependent countries like Mozambique and Malawi, the governments enjoy little policy autonomy to set their countries’ development agendas. Post-settlement South Africa found itself in the fortunate position that it enjoyed almost total control of its agenda, and the development path it would pursue.

Anybody who would like to understand post-apartheid South Africa’s social policy landscape would be well-advised to consult a range of policy instruments and strategic documents which capture the country’s approach to social and development policy. Government’s goals are spelt out in the Constitution; the White Paper on the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP); Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR); State of the Nation Addresses of the President; the Annual Budget of the Minister of Finance; the Strategies of national departments; the Ten-Year Review; the Medium Term Expenditure Framework; the Medium Term Strategic Framework; Integrated Development Plans (IDPs); and the Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative of South Africa (ASGISA)[iv].

Whereas the apartheid state and government were committed to guarantee the security and the prosperity of the white population first and foremost, the post-apartheid government took its leave firstly from the 1996 Constitution, which calls for a ‘progressive realization of rights’, therefore calling for the incremental redress of poverty and inequality. Specifically the Constitution places an onus of responsibility on the state. In the words of the Constitution, ‘The state must take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realisation of this right’. The Constitution is thus clear in that the state must act reasonably and decisively in the sphere of addressing socio-economic inequalities, namely redressing inequalities, and unequal access to housing, electricity, water, health, and other sectors [v].

From a policy perspective, government adopted the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) in 1994, a development vision cutting across all spheres of societal development. The RDP was accepted as the de facto policy framework of the new government, functioning as a ‘blueprint’ for social and political transformation in South Africa.[vi] The RDP was institutionalized in the form of the RDP Ministry and the RDP Fund. The erstwhile RDP office formed a focal point of donor support from 1994 to early 1996. The RDP sought to facilitate cross-cutting policy approaches and encouraged new approaches to public sector management and budgeting to meet government’s overall reconstruction objectives.

Critiques of the RDP’s institutional arrangements and operational mechanisms broadly centred on the increasing understanding within the state that the RDP was not a full strategy for governance and development and was open to wide interpretation.

Government subsequently developed what it said was a more comprehensive macro-economic policy, Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR); there was recognition that RDP priorities would only take place in the context of economic growth.[vii] Thus GEAR is predicated on the need for economic growth and provides a strategic framework within which decisions on monetary, fiscal and labour market policy have been taken since 1996. It involves, inter alia, liberalization of the economy, privatization of government assets and a reduction of state spending. GEAR is a key driver of the government’s trade strategy and has been recognized by the private sector both locally and internationally as a sound economic framework.

But outside these constituencies, GEAR has been consistently criticized by among others, the labour movement and the South African Communist Party (SACP). The view held by these parties is that, even if GEAR does facilitate growth, it will do so in such a way that income redistribution will remain unaffected, resulting in a widening of the gap between rich and poor. These critics argue that poverty is on the increase and the country lacks a comprehensive framework on poverty alleviation.

One response from the state to articulate a comprehensive poverty alleviation framework has been the introduction in 1998 of a three-year budget cycle, the Medium Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF).[viii]

The MTEF’s priorities are as follows:

– Meeting basic needs – principally in education, health, water and sanitation, social services, welfare, land reform and housing;

– Accelerating infrastructure development – ensuring investment in infrastructure, upgrading of roads, undertaking of spatial development initiatives (Spatial Development Initiatives), and addressing urban renewal – principally via private-public partnerships;

– Economic growth, development and job creation – the stimulated building of the economy to achieve sustainable, accelerated growth with correspondent redistribution in opportunities and income;

– Human resource development – the education and training of citizens in pre-primary, formative, tertiary, technical institutions and lifelong education and training for adults, the unemployed and out-of-school youth;

– Safety and security – the transformation of the criminal justice, police and prisons administration and the improvement in national defence and disaster management;

– Transformation of government – the strengthening of administration and good governance and the implementation of a code of conduct (Batho Pele – People First) for service delivery by the public sector.

In terms of funding its national development programmes, South Africa raises the bulk of its resources itself. Donor funding constitutes less than 0,5% of the national consolidated revenue of the country. From around 1998, the social security safety net expanded with the introduction of the Child Support Grant for children between the ages 0 and 7.[ix] In 2003, this increased to cover children 7 to 8 years old. From 2005/06, all children up to the age of 14 would qualify for grants.[x]

The extension of the post-apartheid social security net is one of the greatest successes of post-apartheid South Africa.[xi] The number of beneficiaries increased from 2,5 million in 1997 to 5,6 million in 2003. By 2004, the social grants system delivered about 7,4 million grants; spending on social grants increased to over R40 billion in 2004.[xii] By 2005, there was a further increase in the numbers, with an estimated 9,2 million beneficiaries of the system.[xiii]

In 2003, Cabinet approved the Operational Plan for Comprehensive HIV and AIDS Care, Management and Treatment for South Africa.[xiv] This combined a progressive anti-retroviral roll-out.

More recently, government adopted the Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative for South Africa (ASGI-SA), a broad framework of steps that need to be taken to raise growth to much higher levels.[xv] ASGISA grew out of the 2003 Growth and Development Summit and the Micro-economic Reform Strategy (MERS).

The main focus of ASGI-SA is to deal with a set of binding constraints that inhibit faster growth. These constraints are currency volatility and macro-economic stability; cost and efficiency of the national logistics system; skills shortages; high levels of inequality; barriers to compete in the sector; the regulatory environment for small and medium sized enterprises; and deficiencies in the capacities of government and parastatals.[xvi] A key proposal is to increase infrastructure spending to over R370 billion over the medium term expenditure period, fast track skills development, reducing the regulatory burden on small enterprises and improving capacity at the local and international level.[xvii]

As a development strategy, ASGI-SA does have specific sections on poverty eradication, equity, and distributional issues. First, there is a key Poverty Reduction dimension; this includes budget reform and reprioritisation, increasing access to income and employment opportunities for the poor, including the Extended Public Works Programme, ensuring food security and providing nutrition, meeting the demand of housing, providing comprehensive free primary health care, building and upgrading clinics, and revitalising hospitals and expanding the immunisation programme.[xviii]

Expenditure on HIV and AIDS programmes has increased incrementally over the cause of the past decade. Expenditure across national departments has increased from about R30 million in 1994 to R342 million in 2001/02. Expenditure is set to increase to R3,6 billion in 2006/07, and focuses on prevention, care and treatment.[xix]

In the areas of TB, malaria control, medicine supply, and human resources are priorities. At a broader level, broadening access to, and improving the quality of education, land reform, water and sanitation, universal access to electricity and improving transport are all chief priorities.[xx]

Over the past twelve years, education and health gradually emerged as the two sectors getting most of the budget allocation. This is very important if South Africa is to become a developmental state. Such a state typically prioritises social sectors such as health and education.

It is important to point out here that since the 1997/98 budget, government started to provide for special poverty relief programmes. In 1998/99 these allocations were broadened to include a focus on temporary poverty relief, and extended in 1999/00 to include commitment at the Presidential Job Summit. Programmes funded through this source complemented other key poverty alleviation interventions such as social security grants, and the delivery of basic services to communities like education, health, welfare, housing, water and sanitation, electricity, waste removal and municipal roads.

The 2006 national budget was a balance between addressing the needs and wants of various economic actors. That year’s budget represented an increase in social grants and spending. 60% of the budget went towards social spending.[xxi] In 2008/09, social spending declined to 49,5%, from 51,7% in the previous year’s budget.[xxii] This was mainly because of massive expenditure in energy and infrastructural development.

Institutional arrangements to South Africa’s HDI

In South Africa, several institutional actors play roles in crafting development and social policy in the country. These range from Cabinet, National Ministers and their various Departments, Provincial Premiers, Members of the Executive Councils in provinces, Mayors and local councils, Working Groups, and others.[xxiii] But the Department of Social Development is the pivotal player in the area of social policy, social protection, social security and social affairs. The aim of the Department of Social Development is to ensure the provision of comprehensive social protection services against vulnerability and poverty within the constitutional and legislative framework, and create an enabling environment for sustainable development.[xxiv] The Department further aims to deliver integrated, sustainable and quality services in partnership with all those committed to creating a caring society.[xxv] The Department is responsible for policy and oversight in the critical areas of social assistance and social welfare assistance. Social assistance refers to means-tested cash benefits to vulnerable groups in South Africa, whereas social welfare services refer to probation and adoption services, child and family counselling and support services, and secure centres.[xxvi]

The Department runs approximately nine (9) programmes.

Programme 1 is Administration, and its goal is to provide for policy formulation by the ministry and top management, and for overall management and support services.

Programme 2 is Social Security Policy and Planning. The purpose of this programme is to develop, coordinate and facilitate the implementation of policies and strategies, and facilitate financial planning for social security in line with the national macro-economic goals and development objectives.

Programme 3 is Grant systems and service delivery assurance. This programme designs operational systems to ensure that services are provided to social assistance and disaster relief beneficiaries; it also monitors and evaluates service delivery and compliance to minimize fraud and assess the impact of policies.

Programme 4 is that of Social Assistance. This programme makes funds available to provinces to administer and pay social assistance in terms of the Social Assistance Act (1992), and fund and manage the establishment and development of the South African Social Security Agency.

Programme 5 is Welfare Services Transformation, a programme with the purpose of facilitating the transformation of development-oriented social welfare services to vulnerable individuals, households and communities.

Programme 6 is Children, Families and Youth Development. This programme seeks to ensure the protection and empowerment of vulnerable children, youth and families.

Programme 7 is Development Implementation Support. Its purpose is to develop, implement and monitor strategies to promote the delivery of integrated and well-co-ordinated and well-structured poverty alleviation and community development services to vulnerable groups, households and individuals.

Programme 8 is HIV and AIDS, with the express purpose of developing policies, strategies and programmes aimed at mitigating the social impact of HIV and AIDS. It also seeks to develop and implement strategies for children and families infected and affected by HIV/AIDS, and facilitate the rollout of home community-based care and support programmes.

So, judging from the above, the Department of Social Development is a key, if not the most pivotal player in the area of social development in South Africa. But we have to appreciate that South Africa takes the question of cooperative and integrated governance seriously; thus Social Development was also part of a Cluster System in South Africa. The Social Cluster, which includes the Departments of Social Develop¬ment, Education, Labour, Health, Housing, Arts and Culture, and Sports and Recreation, also plays a crucial role in terms of social policy in the country.

Thus, the question of overseeing the impact of policy-making on poverty, ensuring that the different sectors from transport to health serve the needs of the majority of citizens, involves a number of actors. So, while the Ministry of Social Development is the lead agent in dealing with social affairs, policy and governance in South Africa has become a shared responsibility.

Turning now to the important question of partnerships that exist between public–private sector or civil society organizations, it is important to point out that it has a key responsibility in working with a key civil society partner, and overseeing it, the National Development Agency (NDA). The Department is also busy setting up South African Social Security Agency, a schedule 3 Agency or public entity that will be responsible for administering social assistance grants, and relating to provinces.

Why is South Africa’s HDI so poor?

Why is South Africa’s HDI so poor?

It is very easy and very tempting to do what many analysts do and blame South Africa’s poor human development record just on policies, and to lay the blame especially on ‘policies as pursued by the Mbeki administration’. It has indeed become fashionable to go for such single factor explanations. We are however going to break with what is clearly becoming a trend out there; instead of this quixotic rationale we are instead going to opt for a multi-causal set of explanations and variables that could help to shed light on South Africa’s human development conundrum. This is not to shrug off the centrality of policies adopted by government, and their impact on the human development in the country. It is conceivable that the growth trajectory embedded in South Africa’s policy positions played a key role. It has been said that South Africa has pursued something of a neo-classical, modernisationist economic model during the course of the past decade. Timothy Murithi reminds us that ‘neo-liberal economics’ represent a ‘type of laissez faire capitalism’ which ‘undermines social welfare programmes and creates a fictional perception of a free-market system’ [xxvii]. One of Africa’s most respected development thinkers, Adebayo Adedeji said about South Africa’s GEAR strategy:

Just as the rest of black Africa has failed to deconstruct its inherited colonial political economy, so post-apartheid South Africa, in deference to a compromise based on sufficient consensus, has not chosen the path of fundamental socio-economic transformation.[xxviii]

But the problem was not just policy per se, the problem was also how policy was arrived at, or the policy style, to use a different phrase. In spite of its stated commitment to bring about a Developmental State, government has consistently struggled to mobilise social partners behind an all-encompassing interest – a Social Compact. Government dominated policy-making and social partners, and even those close to the ruling ANC like COSATU, the SACP, and SANCO felt excluded and marginalised from policy processes. Many of them held the view that the Presidency, especially the Policy and Advisory Services (PCAS) unit, dominated policy-making and coordination efforts. Government has to understand that it cannot tackle the country’s vast socio-economic challenges on its own. It needs the efforts of social partners and should therefore democratise the policy, development and governance processes.

The third explanation we have to advance here is that of the enduring legacies of apartheid. It is easily forgotten that the apartheid state left a trail of human misery in its wake, and it will take decades, maybe even centuries to overcome these legacies.

Conclusion: Way forward

South Africa is going through some important changes at a political level. The recall of President Thabo Mbeki, talk of a breakaway party and the increased influence of COSATU and SACP within the ANC are some indicators of these changes. These changes have also brought in their wake an increased sense that there has to be a renewed debate about the way in which the state is challenging and confronting poverty and inequality.

One of the central lessons to be learnt from the last decade is that changes cannot be a top-down process while civil society has to develop strategies to engage with the state. Civil society actors should appreciate their pivotal role in engaging providers of services at local, provincial and national levels, and their place in creating opportunities and space for communities to influence policy and development processes. So, the participatory opportunities for communities to get more directly involved in policy, planning and governance should be broadened.

A partnership and participatory approach presupposes that the skills levels of local government and municipal levels would become more strategic. Skills at this level have been poorly developed and many of them have reached a state of crisis over the course of the last decade.

The capacity of local and provincial government to integrate HDI issues such as gender, HIV/AIDS, the rural question, and other key aspects, into policy needs to be enhanced.

It is absolutely critical that that the service delivery capacity of the state in general, and of local and provincial government in particular be bolstered. At a minimum, the interface between national, provincial and local government spheres must become tighter and better coordinated so as to have maximum impact on the delivery of services.

While the quest to create a more equal society in South Africa has come up against numerous problems and is now faced with a crisis of expectation, there exists an opportunity to put right past mistakes and accelerate the delivery of basic services.

—

Notes

i. Discourse is defined as ‘a set of meanings embodied in metaphors, representations, images, narratives and statements that advance a particular version of ‘the truth’ about objects, persons, events and the relation between them’ (Long 2002: 52). Institutions and actors may have ‘their own’ discourse and way of thinking about development, which may conflict with the discourse owned by others.

ii. See United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report 2007-08, UNDP, New York, 2008.

iii. AFROLNews, ‘Human Development Report Shocks South Africa’, 7 April 2008.

iv. African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), Country Self-Assessment: Government’s Submission, Third Draft, March 2006.

v. Ibid.

vi. For an assessment of the Reconstruction and Development Programme, see Tobie Schmitz and Claude Kabemba, Enhancing policy implementation: Lessons from the Reconstruction and Development Programme, Research report no 89, Centre for Policy Studies, Johannesburg, September 2001.

vii.See Zondie Masiza and Xolela Mangcu, Understanding policy implementation: An exploration of research areas surrounding growth, employment and redistribution (GEAR) strategy, Centre for Policy Studies, Research Report no. 78, Johannesburg May 2001.

viii.This information is borrowed from government’s 10-year review process in which this author is a participant.

ix.Republic of South Africa, National Treasury, Intergovernmental Fiscal Review 2003, April 2003, p. 95.

x. Ibid.

xi. Ibid.

xii. Republic of South Africa, National Treasury, Budget Review 2004, 18 February 2004, p. 121.

xiii.Republic Of South Africa, National Treasury, Estimates of National Expenditure 2005, February 2005, p. 403.

xiv.Republic of South Africa, National Treasury, Budget Review 2004, op. cit, p. 122.

xv. See Government’s perspective on issues raised in the APRM Country Self-Assessment Questionnaire, January 2006.

xvi. Ibid.

xvii. Ibid.

xviii. Ibid.

xix. Ibid.

xx. Ibid.

xxi. See Global Insight Perspective, 18 February 2006.

xxii. See Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), The 2008/09 National Budget, Weather the Storm, Invest for Growth, IDC, Sandton, 21 February 2008.

xxiii. African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), Country Self-Assessment: Government’s Submission, Third Draft, March 2006.

xxiv. Republic Of South Africa, National Treasury, Estimates of National Expenditure 2005, op. cit., p. 403.

xxv. Ibid.

xxvi. Ibid.

xxvii. Timothy Murithi, The African Union, Pan-Africanism, peace-building and development, Ashgate Publishing, 2005, p. 145.

xxviii. Adebayo Adedeji, ‘South Africa and Africa’s political economy: Looking inside from the outside’, in Adekeye Adebajo, Adebayo Adedeji and Chris Landsberg (eds.), South Africa in Africa: The post-apartheid era, University of Kwazulu-Natal Press, 2006, p. 55.

References

Adebajo, A., Adedeji, A. and Landsberg, C. (eds.) (2006), South Africa in Africa: The Post-apartheid era, Pietermaritzburg: University of Kwazulu-Natal Press, p. 55.

African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM), Country Self-Assessment: Government’s Submission, Third Draft, March 2006

AFROL News, ‘Human Development Report Shocks South Africa’, 7 April 2008.

Altbeker, A. (2007). A country at war with itself: South Africa’s crisis of crime,

South Africa: Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Berg, S., Burger, R., Burger, R., Louw, M. and Yu, D. (2006). Trends in poverty and inequality since the political transition, Development Policy Research Unit, Stellenbosch University: Working Paper 06/104, pp. 1-24.

Dickinson, D. (2002) Confronting reality: Change and transformation in the new South Africa, The Political Quarterly Publishing, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers: pp. 1-11.

Gelb, S. (2003) Inequality in South Africa: Nature, causes and responses, The EDGE Institute, Johannesburg, Accessed at: www.tips.org.za/events/forum2004/ Papers/Gelb_Inequality_in_ SouthAfrica.pdf, last viewed on 10 April 2006, pp. 1-21.

Hoogeveen J.G. and Özler, B. (2005). Not separate, not equal: Poverty and inequality in post-apartheid South Africa, William Davidson Institute Working Paper, pp. 739.

Miceli, V. (2004) Ten years of freedom in the rainbow nation, Crossroads, 4(2): 24-43.

Murithi, T. (2005) The African Union, pan-Africanism, peace-building and development, Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, pp. 145.

Seekings, J. (2000) Introduction: Urban studies in South Africa after apartheid, International Journal of Urban and Research, 24(4), Blackwell Publishers: Oxford

Statistics South Africa (2003) South African Statistics 2002, in S. Gelb (ed.) Inequality in South Africa: Nature, causes and responses, The EDGE Institute, Johannesburg, accessed at: www.tips.org.za/events/forum2004/ Papers/Gelb_Inequality_in_SouthAfrica.pdf, last viewed on 10 April 2006.

Statistics South Africa (2003) Census in Brief, in S. Gelb (ed.), Inequality in South Africa: Nature, causes and responses, The EDGE Institute, Johannesburg, accessed at: www.tips.org.za/events/forum2004/ Papers/Gelb_Inequality_in_SouthAfrica.pdf, last viewed on 10 April 2006.

United Nations Development Programme (2008) Human Development Report 2007-08, New York: UNDP.

About the Authors

Anshu Padayachee is currently the Programme director of South Africa Netherlands Programme on Alternatives in Development (SANPAD) South Africa. She was elected to this post after having been the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic) at M L Sultan Technikon from 1998-2002, as well as Acting Vice-Chancellor and Special Advisor to the Vice-Chancellor at Durban University of Technology. She is the co- founder of a pioneering Womens’ NGO in South Africa and continues to be involved as an activist in the area of women’s rights and related issues. She has been involved in management, teaching and research at universities locally and internationally for thirty years. She obtained her Bachelors, Hons and Masters degree in Criminology at UDW and LSE and her D.Phil in Criminology in 1990. She is widely published and continues to write despite having left academia for management.

Ashwin Desai, the holder of a Masters degree from Rhodes University and a doctorate from Michigan State University, is currently affiliated to the Centre for Civil Society at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, and lectures part time in Journalism at the Durban Institute of Technology and The Workers College. Ashwin Desai is one of South Africa’s foremost social commentators and an unusually prolific and wide ranging writer whose work has been published in academic and popular books and periodicals around the world.