Prophecies and Protests ~ Contextualising Ubuntu In The Glocal Management Discourse

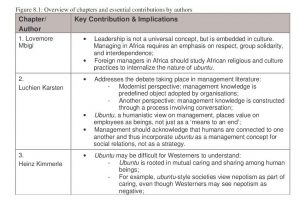

The book ‘Prophecies and Protests: Ubuntu in Glocal Management’ provides a wealth of information on the unique Africa-centered management style based on ubuntu. While it is a monograph about anagement in Africa, it stops short of making the bold claim that Africa-centered management could be wider applicable, for example, in the Western world. However, the book alerts Western companies working in Africa to pay attention to the practices of ubuntu in African companies and its effects on the workforce. Since by definition ubuntu is a human condition, its emphasis on the social interactions of humans as a source of strength and meaning, provides a unique perspective on how leaders can create powerful organisations. A brief overview of the chapter contributions is captured in Table 1 for ease of reference.

The book ‘Prophecies and Protests: Ubuntu in Glocal Management’ provides a wealth of information on the unique Africa-centered management style based on ubuntu. While it is a monograph about anagement in Africa, it stops short of making the bold claim that Africa-centered management could be wider applicable, for example, in the Western world. However, the book alerts Western companies working in Africa to pay attention to the practices of ubuntu in African companies and its effects on the workforce. Since by definition ubuntu is a human condition, its emphasis on the social interactions of humans as a source of strength and meaning, provides a unique perspective on how leaders can create powerful organisations. A brief overview of the chapter contributions is captured in Table 1 for ease of reference.

In essence, ubuntu accentuates the notions of humaneness, sharing, and respecting all by creating great value for a group above pure individual desires and actions (Mangaliso 1992; 2001). It is a self-reinforcing set of beliefs that revolves around the core concept that the strength of any group resides in the relationship of its members. Behind this core concept are beliefs such as:

1. People are not just rational, self-interested beings, but are social beings whose interactions have implications for both the group and individuals within the group;

2. Unity of the whole is more fundamental than the distinction of the parts. Individuals do not act not in theoretical isolation – there is a reciprocal impact experienced within a network of social relationships;

3. Relationships are more important than any given decision or outcome;

4. Inclusiveness in decision-making is more important than speed or efficiency;

5. The broader context is always important, and ‘context’ could be on many levels: overall culture, human dynamics in a meeting, or non-verbal cues in a conversation;

6. The wisdom that comes with experience as valuable as the vigorous energy of youth;

7. Group performance is more important than individual ‘stars’; Strong individual performers are those that help the group the most.

Ubuntu shares some similarity and yet stands in contrast with both the Western and Eastern traditions of management. Similar to ubuntu, Eastern traditions emphasize connections and caring as represented in guanxi in China (Tsang 1998) and kyosei in Japan (Kaku 1997), but unlike ubuntu they tend to strive for constant improvement through highly directive and hierarchical management. Western practices generally emphasize individual achievement, speed, and decisiveness. Relationships tend to be contractual, and true value is measured and rewarded at the individual rather than at the group level. This is in contrast to ubuntu with its emphasis on non-linear, mostly familial relationships which sets it apart as a ‘third way’ of management.

It is useful to view ubuntu as a fully coherent management philosophy rooted in African traditions, not merely as a response to Western thought. As Weir (in this volume) notes, the regions that uphold the philosophy of ubuntu should not be viewed by foreigners as being stubborn, stagnant in the past, or a failed attempt at imitating Westerners. Those regions respect ubuntu because it preserves the values, beliefs, customs, and traditions of its people. Franks (in this volume) points out that ‘improvements’ to traditional societies from the West may be met with resistance because they are an assault to the societies’ customs and traditions. The West and Africa have much to learn from each other, and need to respect the cultural context in which business takes place.

What are the implications of ubuntu for management practice?

Ubuntu gives foreign firms a view into how they will need to adapt to have a successful business organisation in Africa. But beyond enhancing the ability of foreign companies to effectively manage in the African context, ubuntu also has implications for managing in Western and Eastern settings as the authors in this book have pointed out. But quite to what extent the practices of ubuntu can be applied in non-African environments remains to be seen. For one thing, ubuntu collectivism may be confused with the European brand of collectivism which is regarded as too socialistic for most Western companies (Senghor 1965). It might also be considered too non-hierarchical for most Eastern companies. However, these companies can pay heed to the lessons of ubuntu as described in this volume. Several lessons can be applied to Western and Eastern companies like:

Relationships are a source of competitive advantage

Ubuntu philosophy holds that the strength of a group lies in its relationships. Stronger relationships allow for better decisions to be made because people understand each other and can more effectively debate the nuances of an issue as the Mangaliso and Mangaliso chapter shows. Ubuntu views decisions as a point in time, and their outcomes as short-term. Individual skill sets are important, but those skills manifest themselves in most roles only when humans interact. The long-term success of a group is thus based on the relationships within that group. Competitive advantage is traditionally defined as a company having a cost advantage, differentiated value proposition, or domination of a niche. But what capabilities in an organisation enable such a competitive advantage? Ubuntu gives a new view on competitive advantage – relationships provide the organisational capability for competitive advantage. While Western management would cite individual (e.g., executive talent) or organisational skills (e.g., Wal-Mart and low cost inventory management), ubuntu would focus on the actual relationships of executives, managers and workers, suppliers and customers as the capability that enables competitive advantage. Organisations should thus focus on identifying the crucial relationships and fostering them. Western companies tend to focus on building individual skills or ‘teamwork’ – but teamwork is really just combining individual skills.

Relationships are much deeper: they depend on mutual respect and understanding rather than just working with each other. Building relationships focuses on process, not outcome. Similarly, management must make decisions not simply based on facts, but how those facts play out in the context of complex relationships within a firm and with the firm and external parties (e.g., customers).

Meaning conveys more than just rational words

Ubuntu emphasizes the context of words as much as the words themselves. As authors in this volume (e.g., Karsten and Mangaliso and Mangaliso) note, the role of language usage is important, but so are non-verbal cues (e.g., tone, body language), context, and discourse of conversation. In fact, the conversation itself is often just as important as its content. The conversation serves as a means of discerning the underlying relationships between the concepts or criteria used so that a clearer understanding, a vital semantic network, can emerge (Hallen 1997). Ubuntu holds that management must understand the context of the words people use in conversation, as oppose to just the content, in order to establish and strengthen relationships. Western managers can utilize this to make more effective decisions, by understanding the nuances beyond the spoken word. Western managers tend to focus on rational thinking and boiling down information to a few key bullet points to make decisions. By taking more time to understand context, western managers may be able to make more effective decisions. Several of the authors in this volume, including Karsten, point out that management should also encourage conversations amongst individuals in a non-hierarchical manner as this fosters cooperation and establishes a sense of community.

Decisions are stronger when they are inclusive

Ubuntu stresses the importance of looking at an issue from a circular view (e.g., different angles) as oppose to a linear view (e.g., one decision leads to the next). While Western managers emphasize speed and efficiency in decision-making, ubuntu emphasizes improving the effectiveness of decisions by including more people. In both the Mangaliso and Mangaliso and the Mbigi chapters, the point is made that management should favour collective learning and consensus-based decision-making rather than command-and-control. Decisions are stronger when more people are brought into them because new and different perspectives are brought into the decision-making process. Involving people who are not directly ‘responsible’ for a decision will result in better decision-making from incorporating different perspectives. Ubuntu recognises that this will result in slower decision-making – but the long-term effectiveness of decisions is more important the efficiency of speed (which is emphasized in Western cultures). Western management can learn to balance effectiveness/inclusiveness with speed. While certain decisions require a fast decision (e.g., competitive pressure, time-sensitive opportunities), many decisions in business can be slowed down and made more inclusive.

Not just about outcomes – building relationships is important

Being inclusive in decision-making is not just about better decisions; it is about strengthening relationships. Ubuntu downplays the importance of individual decisions in the ultimate success of a firm. The relationships that are forged through the decision-making process are the core to the long-term success of a firm. The principles of ubuntu consider time as a unifying construct that emphasizes interdependence and shared heritage. The Mangaliso and Mangaliso chapter describes how time is not just a series of deadlines, but should be viewed as opportunities to enhance the social network of individuals. Management should emphasize building relationships rather than making quick decisions – this is the secret to long term success. Western management can thus adapt these ideas by paying conscious attention to the process of decision-making. Western managers focus on making the ‘right’ decision and generating the best outcome. However, they can simultaneously focus on building relationships while decisions are being made through encouraging debate, pausing to make sure people understand each other, and fostering a culture of collaboration.

Further perspectives on ubuntu in management

As a management concept with Africa-centered roots, ubuntu can also be considered from an economics and organisational behaviour perspectives. From an economics perspective, organisations – hence management concepts in general – are analysed in terms of efficiency and effectiveness. This perspective is has been overemphasized in management literature to the point of obsession. Mangaliso and Mangaliso cite the Prahalad and Hamel concept of ‘denominator management’ that serves as a guide for profit generation at the expense of all else. Often that leads to a search for the holy grail of the perfect profit-generating machine, that top managers and shareholders dream of for their companies. However, just as the holy grail has never been located, the perfect profit generating machine has not yet been found. The evidence that striving for that goal leads organisations toward a futile direction is vividly depicted in the recent demise of companies such as Enron, Worldcom and Ahold. The chapters in this volume demonstrated that the economic point of view should be balanced with human considerations such as ubuntu.

The organisation behavioural perspective analyses organisations in terms of cooperation and social relations between human beings. The dominant themes are in line with that focus on power, leadership, communication, culture and conflict between groups and individuals in organisations. Among the studies in this genre at least two approaches can be discerned. The first is an emancipatory approach with a focus on the improvement of the position of women, blacks and other minority groups. The second is a status quo approach, which tries to improve human relations within a company instrumentally using structurally and functionally accepted techniques. In the preceding chapters most of the attention has been focused on the first organisational behavioural just mentioned: emancipatory studies into the potential of Africa-centered management.

This book has shown how difficult it is to define precisely, sharply and concisely what Africa-centered management is about, taking into account the multiple perspectives on a central theme like ubuntu. Can a unique management perspective called ‘Africa-centered management’ be found. Opinions of various scholars will differ on this question since a kaleidoscope of ever-changing sub-concepts comes to life most vividly when Africa-centered or Afrocentric management is mentioned. In reality several sub-concepts of what is here called ‘Africa-centered’ are already known and practiced in Western companies. A few examples are discussed below.

From the research on management we can see how complex it is to define management. The whole scale between laissez-faire and authoritarian leadership has been analysed and matched to all kinds of success stories and to many fundamentally different types of organisations. One of the first authors to debunk management into a series of chaotic acts was Mintzberg, in his book the Art of Managerial Work (1980). This disenchantment of ‘management’ left us with a heap of shatters where no real correlations between a certain management concept and the success of a company could be drawn. There is a respectable number of popular management stories about top managers having rescued their business, for example Jack Welsh at General Electric, Lee Iaccocca at Chrysler and Jan Timmer at Philips Electronics. These examples by no means prove the everlasting success of these companies, let alone their styles of leadership. When the top manager in question leaves, the company often slides back into its former problems. In short: the field of management concepts is chaotic. In the preceding chapters we have seen comparisons with Japanese management, which made a victory tour along Western companies in the 1980s. What helped Japanese management tremendously was on the one hand a central focus on delivering quality products for a low price and on the other hand showcases like Toyota, Honda and Sony. In that respect it is lamentable that there is no real showcase to promote Africa-centered management as a management concept. We do not believe that the inclusive, bottom-up orientation is a decisive disadvantage against Africacentered management, because there are several successful Western management concepts with a similar starting point. Quite the contrary, under the rubric of the term ubuntu, it could even be even a strong point in promoting the Africa-centered management style.

Similarities between Africa-centered and Western management

What is fascinating to learn from the preceding chapters is, of course, how many differences exist between Western management and Africa-centered management. Still, we think the similarities are quite as important. To name a few:

– The attention of management thinkers has been focused on human relations, even after the Hawthorne experiments of the 1930s. In these experiments, a greater emphasis on human relations led to better working results (Mayo 1933);

– The advent of the Western school of Organisation Development in the 1950s, with authors like Argyris, Beckhard and Bennis, based on the principles of social dynamics, stresses the importance of social relations within organisations. They claimed that better social relations within an organisation led to a better output of the organisation and to a greater chance of survival for such a company;

– The Peters and Waterman (1982) book, In search of excellence, stressed the importance of culture and values for excellent businesses, instead of high-tech marketing or investment tools;

– Lately, David Maister (1997) did research in the service industry with the same outcome: if more attention is paid to human relations, people are more motivated to work in the organisation and better results will be attained;

– Quite a lot of management thinkers concentrate on the old couple Gemeinschaft versus Gesellschaft (in the terminology of Tonnies 1887), although sociologists consider these terms to be old-fashioned and inappropriate. Gemeinschaft stands for warm village-like relations within companies, whereas Gesellschaft represents impersonal, bureaucratic relations, where people feel alienated, misused and exploited;

– Fukuyama (1995) distinguished ‘high-trust’ and ‘low-trust’ societies, but did not do this according to the distinction of Western versus non-Western. For example, France and Italy are in his view ‘low-trust’ societies;

– The ‘newer’ forms of organisation, like Mintzberg’s adhocracy (1979), in which the mechanism of coordination is in fact back where it started: mutual adjustment, just like in newly started family businesses. People know each other quite well and communicate almost permanently about what has to be done;

– In the Western world there is an abundance of training and coaching companies that train employees in new ways of cooperation, improved communication, and a style of management with more attention and respect for human nature.

Does Africa-centered management have the same potential as Japanese management?

In the 1980s we learned quite a lot from Japanese management. The principles of lean production, quality circles, responsibility for quality positioned in every employee, thorough management development programs to improve communication between departments, management by walking around, being humble as a manager and listening carefully to customers have been picked up almost everywhere in the Western world and perhaps even more in other Asian countries like South Korea, Taiwan and China.

This interest in Japanese management faded away in the Western world after the Japanese economy had declined in the early 1990s. This is in fact remarkable, because this decline cannot be attributed to failing Japanese management. Principles of Japanese management have lost nothing of their actuality and accuracy; one only needs to look at the larger Japanese companies in 2006: Sony, Toyota and Canon represent the top of their economic sector. They are very healthy companies with abundant innovations.

At first people in the Western world were hesitant: can we learn anything from the Japanese? Their culture is so different, Japanese mentality is poles apart from that of people in the United Kingdom or in the United States. Look at the so-called ‘transplants’, Japanese factories in these two countries with mostly indigenous employees working along the lines of Japanese management. The results sometimes even exceed those of their Japanese sister factories. Many Western companies have learned a lot from Japanese management and other companies would have benefited greatly had they learned from these Japanese lessons.

Are these lessons only management concepts passed from the top to the workers in a ‘tell and sell’-way? By no means; the interesting phenomenon in Japanese management is the blending of top-down and bottom-up communication such as Nonaka and Takeuchi’s ‘middle-up-down’ model of organisational knowledge creation. Next to that and fundamental to Japanese management is a long-term time horizon instead of the short-term focus of many Western firms. This means that Japanese management has an eye for long-term opportunities, that is, for durability and sustainability.

Does Africa-centered management have a similar potential for universal use in business as Japanese management does? From reading the foregoing chapters we conclude that it is possible, although it is a pity that really successful company that are run on Africa-centered management principles have still to come to international prominince. Some examples ready for universal use are:

– Ubuntu is beginning to gain international prominence in the scholarly literature with a lot of good ideas and the right flavour of humanness attached to it;

– Bridging conflicts in organisations. Nelson Mandela is an outstanding example of eminent conflict resolution in his country. This can be a powerful learning point for Western organisations, especially when conflicts between sub-groups in society are heating up, as we can watch nowadays;

– Attention for the unemployed, which is very important because of the loss of job opportunities for thousands of employees whose companies are transferred to Eastern Europe or to the Far East;

– Redefinition of the relationship between work and family life;

– A more thorough humane approach to organisations, understanding the differences between people from different backgrounds;

– A less one-sided rationalistic approach to organisations;

– More attention to non-verbal communication within organisations;

– Spirituality in organisations: since Weber’s (1920) Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism, Western organisations have lost their spirituality. Some people even think many Western companies are ‘soulless’.

Concluding comments

Throughout this book we have witnessed the rising of a powerful new species of Africa-centered management applicable to African circumstances, in contrast to Western management, which tries to be universalistic and culture-free. To develop an African way of management is entirely in accordance with the contingency school in management thinking: there is no ‘best’ way of organising and managing. It is a matter of applying the organisational structure, style of leadership and communication required by a certain situation. It takes a lot of fine-tuning to find the right organisational parameters for a certain country and a certain culture, but this is not a problem. Problems arise when general management principles are applied to a specific situation. Local management, however, does not necessarily entail a submitting to irrational beliefs or behaviour that is in conflict with the aim of the organisation.

Having said that, it is not easy to maintain particularistic forms of management in a globalising world where the pace is set by the most efficiently structured and the most effectively run organisations. This means that the bulk of the ‘make’ industry has been and will continue to be transferred to Asian countries, whereas only service and repair industry is left behind in countries that cannot or will not abide with these strict rules. As a good book should do, this book raises more good questions than it provides solutions! We think that we should consider the questions and solutions that Africacentered management has to offer very seriously, because we have to think across borders of countries and continents to solve these problems.

The contributors to this book have offered its readers a unique opportunity to become aware of and better understand the Africa-centered concept of ubuntu. The authors acknowledge ubuntu’s significant role in African society and African style of management and discuss how understanding its principles can benefit and influence both Western and Eastern management thought. It is also worth reiterating that the fundamental essence of ubuntu is very difficult to fully interpret if one is an ‘outsider’, or, to quote Kimmerle in this volume, trying to understand ubuntu from the point of view of a ‘westerner’. Boessenkool and Van Rinsum found that only through an active effort to learn the ‘spirit’ of its underlying values and history, in addition to participation in open conversations, can one begin to grasp ubuntu. Hopefully this book has served to reveal to that spirit.

References

Fukuyama, F. (1995) Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity, New York: The Free Press.

Hallen, B. (1997) African meanings, Western words, African Studies Review, 40(April): 1-1.

Kaku, R. (1997). The path of kyosei (cooperation), Harvard Business Review, 75(4), July-August: 55-9.

Maister, D. (1997) Managing the professional service firm, New York: The Free Press.

Mangaliso, M.P. (2001) Building competitive advantage from ubuntu: Management lessons from South Africa, Academy of Management Executive, 15(3): 23-33.

Mangaliso, M.P. (1992) Entrepreneurship and innovation in a global context, Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Change, 1: 437-50.

Mayo, E.G. (1933) The human problems of an industrial civilization, New York: MacMillan.

Mintzberg, H. (1973) The nature of managerial work, New York: Harper & Row.

Mintzberg, H. (1979) The structuring of organisations: A synthesis of the research, New York: Prentice-Hall.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995) The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation, New York: Oxford University Press.

Ntumba, M.T. (1985). Langage et société. Primat de la Bisoité sur l’intersubjectivité, Recherches Philosophiques Africaines, 2, Kinshasa.

Peters, T. and Waterman, D. (1982) In search of excellence, New York: Harper & Row.

Senghor, L. (1965). On African socialism, New York: Stanford.

Tönnies, F. (1887). Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft, Abhandlung des Communismus und des Socialismus als empirischer Culturformen, Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag (R. Reisland).

Tsang, E.W.K. (1998) Can guanxi be a source of sustained competitive advantage for doing business in China? Academy of Management Executive, 12(2): 64-73.

Wallraff, G. (1988) Ganz Unten: Mit einer Dokumentation der Folgen, Köln: Kiepenheuer and Witsch.

Weber, M. (1934) Protestantische Ethik und die Geist des Kapitalismus, Thübingen: Mohr.

Weber, M. (1958) The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, New York: Scribner.