Prophecies And Protests ~ The Scope For Arab And Islamic Influences On An Emerging ‘Afrocentric Management’

Abstract

Abstract

As there is in the global world of management a diversity of cultures and differing norms of behaviour so there is more than one ‘culture of management’: yet little attention has been paid to the ethical and philosophical bases of other paradigms than those with which we in Western business schools are familiar.

Where other philosophical and ethical systems are encountered, they are apt to be dismissed with the discourse of ‘traditionalism’ or ‘underdevelopment’, or stigmatized as inconsistent with the requirements of business efficiency. Many of these systems of ethics are embodied in cultural traditions that are, in origin, older than those of Western capitalism, yet in contemporary societies these may be evolving and transmuting radically, so it may be incorrect and unhelpful to see these economic systems as deviant cases or as unsuccessful attempts to reproduce Western modalities.

This paper draws on extensive research by the author and colleagues in the contemporary Arab world to identify the values under-pinning management in the Near East, Middle East and North Africa, and to analyze the opportunities for corresponding styles of leadership and management in certain regions of Africa. We suggest that these Islamic values may exert a growing influence on the emerging ‘Afro centric’ models in the Twenty-first century.

It is not claimed that these models of management are especially relevant for African conditions, but they may be and that is for scholars and business-people more familiar with Africa to determine. But it is to argue that they should be more widely understood and studied as a counter-weight to the pervading emphasis on the hegemonic models derived from the historically-specific legacies of the western and colonialist worlds.

In the first section we review the background to management in the region, in the second we review relevant research frameworks and findings, in the third section we focus on the defining elements of Islam as this relates to business, then we examine the impact of modernity and in the final section we discuss some future trends of especial import for emerging paradigms of management in Africa.

The Middle World

A well-known saying among the Bedouin of the Middle East goes as follows: ‘It is written: the path to power leads through the palace, the road to riches lies through the market, but the track to wisdom goes through the desert’. In the West and especially in business schools we tend to assume that we have the best maps to all of these three routes, and that they lead to places we already know about. So the paradigms of management on which we base our instruction in these academies are those with which we are already familiar. But we may be wrong in these assumptions for in fact we know very little about the Arab and Islamic worlds and their special ways of managing and their different approaches to money and wealth (Weir 1998). We also know rather little about ‘African’ styles and patterns of management; though hopefully this book will do something to redress that balance. Nonetheless what counts as ‘management’ in most of the pedagogic and research literature with which we are in principle familiar is in fact derived from what we know about Western management and business and from what we have learned about our varied attempts to introduce those models into other contexts. Thus we tend to problematise the issues that arise from these ventures at intellectual colonisation and to hold the Western models as ‘normal’.

Indeed, perhaps because Africa experienced the impact of European colonialism more directly than the Middle East, scholars in the West tend to know more about Africa than they do about the Middle East. To the Middle East let us heuristically add the largely Muslim lands of North and West Africa and we have defined a region that I will call for the purposes of this exposition the ‘Middle World’. This is a region that impacts on Sub-Saharan Africa in many ways.

That is not to imply that there is a simplistic type of cultural development that is exclusively ‘Arab’ or ‘Islamic’ or even ‘African’ but to try and roughly delineate a domain in which these strands of management and cultural thought continuously combine in a complex, dynamic process that will undoubtedly emerge into some pattern that is recognisable sui generis but will nonetheless also contain elements whose history and specific evolution will mark their origins. Therefore we must not essentialise these strands any more than we should essentialise ‘management’ in the recognisably Anglo-American patternings that frame much of management ducation in the Western world.

The interpenetration of inter- and intra-continental histories vastly predates modern times. Now we have some new beginnings in Africa; and we also have some old legacies. Some but not all implicate Western management philosophies and practice and we need to generously expand our models the better to comprehend the scale of the historical opportunity. Some analyses relating to Africa are based on the discourse of ‘development’; some on the geo-political certainties that guide our political strategies; some on the presumed historical inevitability of the economics of ‘globalisation’. But usually the underlying models of development are drawn from Western models and mirror Western expectations.

The West has its own ideas about Africa and in contemporary debate these often problematise the post-colonial features of African life and society. But the Arab experience of Africa and Africa’s experience of its neighbours to the North and East together comprise a much wider and continuously inter-penetrating history. Colonialism is a minor eruption on the broad skin of African-Arab interaction, and Islam is and has been in many ways even more influential over a longer period in this continent than Christianity. Sometimes this emphasis on the peculiarly Western experience of Africa has led to historically inept theorizing, even to moralizing. Thus, the West, and Britain and the USA in particular, tends to accept a unique collective blame for the evils of slavery, while most scholars agree that slavery was both an Arab and an indigenous phenomenon long before the Western powers entered the scene. Sometimes it is arguable that in some ways Western writers and researchers have almost feared to study the Arab ways of doing business and have implicitly shared in the common perception of the Arab as the ‘dangerous other’ (see for instance, Weir 2005b).

It is not clear that either Africa or the Middle World must follow the paths to economic development prescribed by Western institutions or favoured by Western scholars. Thus the analyses of such scholars as Bernard Lewis may miss the mark. In loudly declaiming the ‘failure’ of the Arab world to modernise at the same rate and in the same way as European and American exemplars of development in such tracts as ‘What went wrong?’, Lewis and his collaborators are eschewing the plausible explanation that these societies may not be on the same tracks to the same destinations (Lewis 2002). Most economies in the world plan to ‘grow’; but it does not follow that all will do it in the same way. Every major economic culture sustains in its business activity and management practices a recognisable pattern of beliefs and processes that relates in a functional and supportive way to the generic culture in which it is embedded. Management has to lie within its culture rather than to be in opposition to the main trends of thought in the major axes of societal configuration.

In this paper we introduce some of the basic cultural features underpinning the values supporting management in the Middle World. Despite the fact that this world stretches from the Mauretanian coast of West Africa at least until the Straits of Hormuz which mark the limits of continental Arabia, and impacts directly on all the European, Balkan and Turkic countries of the Mediterranean basin, management and business practices in this region remain a relatively understudied phenomenon. (see for example Weir 2000a). Recent American policy pronouncements about ‘The Greater Middle East’ imply a growing comprehension in Washington about the geo-strategic significance of the region. But our focus should not only be on what is occurring in or adjacent to the Arabian peninsula for it is Africa that constitutes in many respects the largest element of this ‘Middle World’ and there are more Muslims in Africa than in the Arab heartlands.

But while the impact of this region on the global economy is increasingly significant management practice within it has been relatively little studied until recently. The analysis in this paper is based on research over the past thirty years by the author and collaborators including many of my doctoral students to whom I owe an inestimable debt. These studies have been carried out in the whole region including Saudi Arabia, the other Gulf co-operation Council states, Iraq, the Maghreb countries including Algeria and Libya, as well as in Palestine, Jordan and Yemen (Weir 2000a).

These regions are diverse and generalizations about such diversity are inevitably dangerous. But there is a clear sense in which the countries of the Middle World are in several key respects culturally homogeneous, due to the cultural dominance of a unifying religion, Islam. Over the world as a whole, Islam accounts for approximately 20 per cent of the world’s believers and is becoming increasingly prominent in other regions, not least in Europe and the USA. But we do not argue and it would be facile to do so, that what we describe as ‘Islam’ exists or operates in precisely the same way to influence patterns of general culture or specific management practices in every place where Muslims are to be found. But there are some unifying features and it does claim to be a universal religion.

Some common features frame the experience of these countries of the Middle World, including as well as the religious framework of Islam, the Bedouin, Touareg and tribal ancestry of many peoples in the region, the experience of foreign rule, repeated and continuing foreign intervention and attempts to control the access to oil and natural resources in the region that have led to rapid economic development in certain parts. But these elements are by no means of equal impact in the historically specific experience of all countries in this region. (Chennoufi and Weir 2000; Weir 2000b). It is not our intention to over-generalise or to claim the universality of any of historical paradigm but to review some features of the economic and business models of the Middle World that may have special relevance for an emerging ‘Afrocentric’ management.

Some Arab countries are not oil-rich and not all have had the same experience of foreign domination. In particular, there are strong differences between the largely French and Spanish influence on the lands of the Maghreb and the largely British influenced Near and Middle East. Moreover, while the creation and growth of the state of Israel since 1948 is of considerable political and ideological significance for all these states, its economic impact is more relevant to some than to others.

Recent research based on empirical studies has permitted the development of new typological frameworks. The widespread impact of investment in education and training and the strong emphasis on management development permeates the Arab world, particularly, but by no means exclusively, in the oil-rich areas exposed to Western influence. In some states in the Gulf, the spur to research has come through the political requirement of ‘nationalization’, the replacement of expatriate managers with nationals.

Many countries in the region, particularly around the Arabian Gulf, tend to have highly trained managerial cadres. Lifelong learning is an implicit expectation, not an imposed obligation. The apparently restrictive requirements of Islamic finance and banking have not hindered economic development in countries like Bahrain, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates. Leadership control through close supervision and an absence of delegation have not inhibited effective performance. There is currently a strong emphasis in Jordan in particular on the role of women and on support for entrepreneurial development and assistance for family-owned businesses. Although the Middle world shares many problems and issues with the West and with Europe, as well as with the USA, considerable evidence is building up that Arab management in particular will present a ‘fourth paradigm’ and is sui generis. The Fourth Paradigm is a characterisation of the management styles and processes in the Arab world that distinguishes it from those practised in the Anglo-American, Japanese and European organisations (see Weir 1998). It is by no means our intention to minimise the differences that certainly exist within this paradigm, nor to imply that these are insignificant, but to paint a broad picture of an overall reality that is in many ways quite distinct from the predominant Western models that form the basis of most business school teaching.

Comparative research frameworks

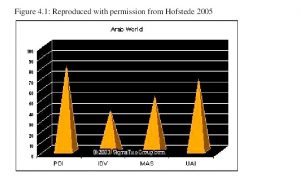

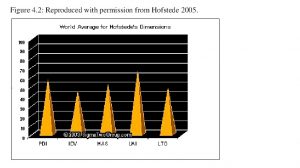

Some of the research into comparative management styles and inter-cultural comparisons has been stimulated by Hofstede’s typology (1991) which provides a widely-understood framework; Hickson and Pugh (1995) have also examined Arab styles and cultures of management. We review these contributions briefly. They are of course generated within the largely Western traditions of comparative management research and have not been built up hermeneutically from within the traditions of scholarship and research that prevail in the region. They are views from outside Plato’s cave, not from the shadow-watchers within. The interpretation of the patterns described by Hofstede and others is not necessarily un-contentious. It is not always clear that like is being compared with like or that Hofstede’s dimensions are capable of simple cross-cultural translation.

Hofstede is concerned with differences among cultures at national level and the consequences of these national cultural differences for the ways in which organizations are structured and managers behave. His basic typology deals with a number of dimensions: the way in which individuals relate to society and handle problems of social inequality, the relationships between individuals and groups, concepts of masculinity and femininity, and ways of dealing with social and interpersonal uncertainty relating to the control of aggression and the expression of emotions. The countries from which his Arab sample was drawn include Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. He claims that these findings ‘demonstrate that the Muslim faith plays a significant role in the people’s lives’.

In specific terms the Arab States typically score highly on the power/distance index. Societies of this kind are characterized as those in which skill, wealth, power and status go together and are reinforced by a cultural view that they should go together. Power is based on family, friends, charisma and the ability to use force. Theories of politics which are influential in Arab countries stress the need for power and leadership and the requirements for decisive action in civil as well as in military society. But absolute power, while it undoubtedly exists in some nations in the region, is not universally admired as a value by managers and professionals who recognise that power needs to be exercised with restraint.

In terms of individualism and collectivism, Arab societies, according to Hofstede, rank in the middle of the individualism index. They are moderately masculine, but there are strong sex role distinctions and the role of women is clearly identified as lying within the family domain. In terms of uncertainty avoidance – the extent to which members of a culture feel threatened by uncertain or unknown situations – the Arab countries again fall between the extreme positions. They are not frightened of other cultures, nor do they wish to become assimilated to them. The Arab countries are classified as moderately oriented towards the avoidance of uncertainty. They undoubtedly also stress the importance of family and kin relations. These dimensions are clearly different from the comparative scores for the world as a whole.

This fundamental characterization points in the minds of many Western commentators to the importance of tradition in Arab culture. Others have argued that the fundamental matrix of Arab social organisation is essentially hierarchical and neo-patriarchal representing in some sense a facsimile of the family and kin structures which permeate Arab society (see Sharabi 1988). Empirical research largely supports this conclusion. Sulieman, for example, in a study of Iraqi managers, points to the influence of family and kin relations in understanding the Arab manager’s use of time and the organization of the working day. Where a close family member appears at the office of even quite a senior manager, it is regarded as improper for the demands of organisational hierarchy to take precedence over the obligations due to family and kin (Sulieman 1984). Hickson and Pugh identify four primary influences over Arabs in general and over management in the Arab world. These derive from the Bedouin and wider tribal inheritance, the religion of Islam, the experience of foreign rule, and the impact of oil and the dependence of Western Europe on the oil-rich Arab states and their distorted economies (Hickson and Pugh 1995).

These four influences are also mediated by the experience of urbanization, which ranges from the extremes of Cairo, one of the world’s oldest continuously occupied cities, to the city states of Dubai and Abu Dhabi which have been created by the sudden increase in prosperity due to the enormous riches of the oil boom.

The Bedouin influence, with its emphasis on the patriarchal family structure, can be seen in the structure of many organisations in the region in which which top-down authority is the norm. In these systems, legitimate authority rests ultimately on the apparently absolute power of the chief person, the Sheikh, who none the less must take account of tribal or organisational opinion in all his decisions.

This structure represents a classical matrix of authority that is still evident in many Arab organisations. But it is modified in particular by the widespread use of expatriate managers in many of the GFF countries. These managers are often of Western or Indian sub-continental origin. The actual senior line management in a specific organisation may be headed by an expatriate, usually though not invariably by an Indian; but behind and above this formal position stands a power that is ultimately that of the ‘Sheikh’ whose authority is super-ordinate over the management systems and structures. Sometimes the exact location of this power is opaque, and not clearly related to formal patterns of ownership, but it is there. The structures may in some cases be virtual, but the power relations are real and influential. A ‘Sheikh’ may not be a permanent status as the possession of relevant authority may be context-dependent.

That is not to say that all business organisations are readily identifiable as ‘Sheikhocracies’, to use Dadfar’s terminology. Nonetheless those who hold power in one context may be assumed to be influential in other contexts also. This ‘classical’ Bedouin structure is characterized as ‘Bedouocracy’ or ‘Sheikhocracy’ by Dadfar (1993), a typology based on an overview of empirical research in Syria, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States, and based principally on the Hickson and Pugh approach. The field studies generated 112 variables which were resolved into a number of socio-cultural dimensions. These included: macrocosmic perception, microcosmic perception, familism, practicality, determinism, time horizon, Western lifestyle, Western techniques and technology, and male/female equality. Dadfar relates these value systems to Arab personality types to create a profile intended to characterize the diverse managerial behaviours found in the Arab world.

Dadfar’s work is unusual in that it is based on a considerable volume of data and sophisticated data analysis. It demonstrates the inadequacy of many of the simplistic previous accounts of Arab management styles in terms of ‘traditionalism’, ‘conservatism’, ‘autocracy’ and the like. I argue with Dadfar that the discourses of ‘traditionalism’ and ‘conservatism’ that are often encountered in Western typifications of the cultures of these regions are misleading; the reality is too complex to be captured by the simple antithesis of ‘Western/modern/secular’ with ‘Arab/traditional/religious’. One of the major empirical studies of management in the region was undertaken by MEIRC, published as The Making Of Gulf Managers (Muna 1989). 140 managers were interviewed in 53 different organisations. The authors identified five main ingredients for success among managers in the Gulf States: a good educational headstart, early exposure to successful role-models, early responsibilities in the home or around it, the importance of an ethical system which puts a high value on hard work and commitment, and the need to take one’s own initiatives in self-development. The study confirms the findings of more impressionistic studies that indicate that Gulf managers prefer a consultative decision-making process.

A striking finding of the MEIRC report and of other studies is the perceived importance of education and training among managers in the Arab world. Organisations in the Gulf countries spend three times as much money and time on their management development every year as do their counterparts in the UK. A larger proportion of managers in the Gulf hold university degrees and indeed postgraduate qualifications in comparison with their counterparts in the USA, UK, France, Germany or Japan. Many organisations had formal career development systems and professional development programmes. These are not recent developments but represent trends that have been visible for some time (Al Hashemi and Najjar 1989).

Managers in the Gulf region are positive towards management training. The MEIRC study concluded that Gulf managers appear to be much better balanced than their Western counterparts in terms of work and family. Personality profiles show managers to be very similar as a population to Western managers, tending to be doers rather than thinkers and planners. Arab managers are adept at working in multinational environments. They revel in the kind of work culture that fosters good interpersonal skills and the techniques of relating well to others. Shared values are important to the managers and they value explicit corporate cultures based in ethical principles. Other studies show a strong emphasis on Western-type management development and training practices as characteristic of the more sophisticated companies in Jordan (Abu-Doleh and Weir 1997).

Managers in Arab countries share a belief in the positive value of change. This is unsurprising because they have experienced more rapid change in their own lifetime than most managers elsewhere in the world. But they are prepared to move up the learning curve at a brisk rate, embracing such contemporary practices as TQM wholeheartedly (Medhat Ali 1998). As managers, they share many behaviours and attitudes with their professional peers in other cultures (Hala Sabri 1995).

These expressions of value do not sit well with the discourse of ‘traditionalism’ and ‘conservatism’ applied by Western writers like Lewis or even with the critique of Sharabi and others that the Middle World is characterised by ‘neo-patriarchy’. (Sharabi 1988). Sharabi has argued that there is a burning need for the Arab world to create its own discourse of modernism to cope with the failures to modernise.

Arab managers nonetheless tend to perceive themselves as well-trained, professional, and in a quite explicit sense as ‘modern’. Neither, though, is there any overt cynicism or duplicity in the expressed desires of younger, well-qualified, professional managers to assimilate the practices of efficient management to the cultural matrix of their own societies and up-bringing. Their expressed interest in concepts like ‘democracy’ does not imply, either, that there is equal enthusiasm for the whole apparatus of Western cultural expression that, in the West, is often taken to be co-terminous with ‘democratic values’.

Islam

Among the prime influences on this region and its cultural matrix are the beliefs and practices of Islam, which is the religion of the majority of inhabitants in this region, and the official religion of most of the political entities. But Islam itself is a complex religious system, with many variations on an apparently uniform pattern of basic beliefs and behaviours. In principle though, the similarities are more significant than the internal differences, for Islam is seen as a universal matrix.

The Arab and the Islamic worlds do not map exactly. The Arab world is not entirely (though it is now largely) Muslim and the largest Islamic countries are not Arabic. But the geographical Arabia is the epi-centre of the Muslim faith and the location of its most holy places, including Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem.

In principle Islam represents a pattern of behaviours and beliefs that affect the whole of human life, no segment being exempt. This is a fundamental tenet of the faith that is explored in detail in terms of its implications for economic behaviour in a comprehensive treatment by Abbas Ali (Ali 2005). Thus to a believer, economic and business life are governed by precepts which can be known and ought to be followed. In principle also, although there are people who know more of religion and whose studies and experience make their views of especial importance, Islam does not depend on any intermediary roles like those of priests or monks to intercede between humans and God. The duties of the Faith are laid equally on all believers and are nonnegotiable. Islam is a universalizing religion though not necessarily a proselytizing one in the same sense as the Christian missionary churches.

Abuznaid provides a concise review of the Islamic values related to managerial practice in the occupied territories of Palestine that in some respects represents a more secular life-style than in the Gulf Co-operation Council states for instance (Abuznaid 1994).

The ‘Five Pillars of Islam’ are well-known:

– The Testimony of Faith;

– The Duty of Prayer;

– The Requirement to provide Zakat for the needy;

– The Duty of Fasting during the Holy month of Ramadan;

– The Obligation to make the Hajj or pilgrimage to the Holy Places of Mecca.

These practical obligations contain the structural foundations of the ethical basis of all behaviour for a believer including the beliefs and practices of management and business life. While they may be detailed and specified by subsequent interpretations, behaviours which are incompatible with these foundations cannot be ‘halal’ or acceptable; they are ‘haram’ or unacceptable. Their strength is in their simplicity and incorrigibility; these fundamental principles are universally adhered to by all believers. Thus they condition the content of belief and practice in all areas of life and the distinction in Western philosophy between the ‘secular’ and the ‘sacred’ does not obtain in these societies for in principle there is understood to be a common texture to all social life and there is a basic ethical framework for business and administration which differentiates management in Arab countries from that in the West.

Islam does not separate religious and state authority in the way that appears normal in such countries as France in the more culturally diverse West. Even revisionist scholars like Tariq Ramadan start from this fundamental presupposition (Ramadan 2001). In the extreme case of scholars and activists like bin Laden the more extreme demand is made that these two dimensions of religious and political authority should be united in a new version of the caliphate (bin Laden 2005: 121) but these are highly contentious theories to which possibly only a few Muslim subscribe. One of the great paradoxes of the Islamic world at present is that the heartlands of faith, the holy places of the religion are mainly located in the Arabian peninsula in the Saudi kingdom that is dominated by an especially dogmatic and severe version of the faith, the Wahabi strain. Another is that the city of Jerusalem, regarded as the third holiest place of Islam is currently occupied by the state of Israel. One of the ironic features of the recent Western invasion of Iraq in pursuit of ‘Islamic terrorism’ was that Iraq was one of the very few countries in the region that had espoused a secular constitution. It has been an apparently unintentional consequence of Western policy to successfully Islamicise a national resistance movement.

Above all, Islam is a religion of practice and publicly visible behaviours, rather than of private inner belief. It seems to be quite possible for a person who prays five times a day to announce that ‘I am not religious’ and for this to be understood. The public manifestations of business and management are equally as much governed by the precepts of this belief-system as any other sphere of behaviour. No aspect of public or private life is exempt.

The unity of Islamic involvement is expressed in the concept of the ‘Ummah’ which identifies the community of all believers who are in practice joined as they touch the ground during prayer. The Ummah is universal and indivisible, representing in a real sense a ‘body’ in which the individuals who believe inhere. Thus to attack the Ummah at any one point implies damaging all of it. This idea clearly posits a different positioning for individuals in relation to other individuals in a collectivity compared to the Western conceptualisation of individuals as ends of moral actions in their own right. Personal value comes from participation in the Ummah, rather than from individual essence or original natural rights.

This conceptualisation impacts quite directly on the presuppositions which underly the differing bases of economic science in the West and in the Islamic worlds. Economics is treated in the former as a division of positive science in which the units, the economic actors, are individuals; it is they who have tastes, wants, desires and can express demand and offer supply; it is these specific actions which can be particularized and identified as ‘economic’. In the latter, economic actions are governed by the implacable philosophy of Islam which applies to all social behaviour; some actions are permitted and are ‘halal’, others are not permitted and are stigmatized as ‘haram’.

The antecedents of some of the theories and philosophies which affect the practice of management in the Arab Middle East therefore are not in practice drawn exclusively, if at all, from the classical Western traditions. Some concepts which appear to carry the same implications as in Western usage derive from different intellectual contexts. Mubarak has shown how even such a familiar concept as ‘motivation’ can be traced to the corpus of Islamic scholarship and located in the writings of Ghazali and Ibn Khaldun as well as Maslow, Herzberg and Taylor (Mubarak 1998).

So even where words like ‘motivation’, ‘leadership’, ‘incentives’, ‘management’ and so on are used in discourse the context and connotation may be different from Western usage. In Africa also as Mangaliso and others have shown, the discourse of management has to negotiate its way among a range of folk and social belief systems that do not necessarily derive from Western values (Mangaliso 2001).

A growing corpus of researches reports on the impact of Islamic imperatives, some of them formally embodied in law, on the practice of business and management. A specialized subset of these concerns is represented by the studies of Islamic banking and financial institutions. These are characterized by differing accounting and financial concepts from those that form the basis of Western financial and accounting theory; in particular, the avoidance of interest on financial capital. This is rooted in a basic moral concern to avoid usury (see for more detailed explanations Shubber 2000 and Ramadan 2001).

The basic ideas of Islamic finance are simple and non-contentious among Muslims. They can be summed up as follows:

– Any predetermined payment over and above the actual amount of principal is prohibited. Islam allows only one kind of loan and that is qard-el-hassan (literally a good loan) whereby the lender does not charge any interest or additional amount over the money lent;

– The lender must share in the profits or losses arising out of the enterprise for which the money was lent. Islam encourages Muslims to invest their money and to become partners in order to share profits and risks in the business instead of becoming creditors. Under Sharia’h law, Islamic finance is based on the beliefthat the provider of capital and the user of capital should equally share the risk of business ventures, whether those are industries, farms, service companies or simple trade deals. Translated into banking terms, the depositor, the bank and the borrower should all share the risks and the rewards of financing business ventures. This is unlike the interest-based commercial banking system, where all the pressure is on the borrower who is expected to pay back his loan, with the agreed interest, regardless of the success or failure of his venture. The principle which thereby emerges is that Islam encourages investments in order that the community may benefit;

– Making money from money is not Islamically acceptable;

– Money is only a medium of exchange and may be a way of defining the value of a thing; it has no value in itself, and therefore should not be allowed to give rise to more money, via fixed interest payments, simply by being put in a bank or lent to someone else. The human effort, initiative, and risk involved in a productive venture are more important than the money used to finance it. Muslims are discouraged from keeping money idle so that hoarding money is regarded as being unacceptable;

Gharar (uncertainty, risk or speculation) is also prohibited;

– Under this prohibition any transaction entered into should be free from uncertainty, risk and speculation. Contracting parties should have perfect knowledge of the counter values intended to be exchanged as a result of their transactions. Also, parties cannot predetermine a guaranteed profit. Therefore, options and futures are considered as un-Islamic and so are forward foreign exchange transactions because rates and earning possibilities are determined by interest differentials;

– Investments should only support practices or products that are not forbidden – or even discouraged – by Islam. Trade in alcohol, for example should not be financed by an Islamic bank and a real-estate loan could not be made for the construction of a casino or a brewery.

A fundamental ethical feature of Islamic finance is thus that of profit and loss sharing. The rate of interest concept which entitles the original owners of financial capital to earn, regardless of the economic success or otherwise of the enterprise in which they are investing, is regarded as improper in Islam.(see Al-Janahi and Weir 2004) There is a general ethical principle that wealth, which can only be created by God, should not be diminished by human agency. This implies that the role of management involves the notion of stewardship of scarce resources, and the role of the financial structures must include maintaining value and minimizing waste of wealth. This in turn impacts on financial and managerial concepts of risk, which leads to a greater involvement of financial institutions in the business affairs of their customers and depositors and thus approximates more closely to the German or Japanese model of long-term joint involvement in economic affairs rather than the Anglo-Saxon concept of short-termism and optimization of financial returns. It also involves banks and financial institutions in the realities of commercial and industrial enterprise (see Al-Janahi and Weir 2005a).

This is not to say that this system does not involve detailed controls of financial performance. Banks and financial institutions that aim to comply with Islamic law must subscribe to a system of audit controlled by the Sharia Supervisory Board. This, as well as supervising the audit function, also oversees the function of Zakat (an essentially voluntary, but none the less expected, donation from the wealthy and prosperous owards the less well-to-do).

The concept of Zakat underlies the Islamic concept of social provision. It is not based on collectivist and universalist principles guaranteed by the state, as in some Western and socialist countries, but is underpinned by the Islamic conception of responsibilities owed by individuals to other individuals. There is variability in the extent to which these simple principles guide the actual financial behaviour of managers in these countries. However, there is a widespread understanding that they represent the ultimate touchstone according to which financial transactions should be judged. The enormous financial success of many Arab corporations gives some indication of their utility.

Financial management under Islamic law and the dynamic potential of Islamic financial management are contrasted by some writers with the ‘sterile mathematical models’ of the West (Jabr and Amawi 1993). Other writers point to the concordance of many aspects of the Islamic approach to finance and business, for example the critique of usury, with earlier traditions in Western economic thought. But it is a great mistake to think of these arguments as of merely historical or archaeological significance. Islamic economics is a substantial and growing intellectual force in which most contributions have been made in the last twenty years. This is a current and dynamic area of scholarship and intellectual endeavour. The Islamic Finance Forum meets twice a year to provide opportunities for scholars and industry experts to report on this rapidly-expanding field (see bibliography for web reference).

Likewise it would be a mistake to ignore the critical and fissile aspects of this discourse, in relation to management, organisation structures and human resource issues as well as finance. The hierarchical and patrimonial nature of authority in Arab organisations does not guarantee efficiency and effectiveness, and it is important not to substitute statements of belief and aspiration with descriptions of reality. There are many studies of the negative impacts of bureaucracy and inefficiency in the Arab and Islamic societies, often rooted in an exaggerated concern for official form over the realities of commercial necessity (see Younis 1993).

Modernity and tradition

The dual pull of tradition and modernity is evident in the characteristic responses of Arab managers to the problems of managing authority and relationships in organisations. Al-Rasheed has compared managerial practices and organisation systems in comparable Western and Arab situations. His study illustrates that the personalized concept of power leads to feelings of uncertainty and loss of autonomy among lower level organisational participants. Conversely, when problems occur, they tend to be ascribed to personal failure rather than to organisational or administrative shortcomings (Al-Rasheed 1994).

Leadership is a complex phenomenon in Arab organisations and is closely tied up with the concepts of shame and reputation. Arab culture, in common with cultures of the Mediterranean regions has been characterized as a ‘shame culture’ rather than a ‘guilt culture’. This governs relations in all areas of social life. For a female to lose her chastity brings shame upon her family, not least on her father and brothers for their failure to protect her honour. For a senior person to fail to provide hospitality for a guest is equally shameful. A good leader is one who arranges matters so as to protect his dependants from shame (Peristiany 1966).

Leadership is a fundamental aspect of life in the Arab world, but its connotations are not necessarily the same as those in the West. The ‘leader’ is one who is regarded as acceptable by peers or colleagues to guide activities, ensure progress towards some agreed goals and to co-ordinate disparate efforts. There is not necessarily an agreed formula for deciding who will lead; while there are ‘royal’ families, it is not necessarily the eldest male who inherits the crown; while the descendants of the Prophet are accorded significant respect, they do not have a ‘natural right’ to leadership. Leaders in one context may not become the leaders in another. A study of Palestinian companies indicates that the most common model is control through close supervision. Thus plant managers go to considerable lengths to demonstrate that they are highly active in supervising the behaviour of employees who cannot be trusted to act responsibly of their own accord (Nahas et al. 1995).

An early study based on empirical research into behaviour and attitudes among Arab managers is The Arab Executive (Muna 1980). The personalization of relationships within Arab life is indicated by the fact that Muna thanks personally all the executives who participated in the study. Muna claims that the typical form of decision-making in Arab organisations is consultative. Delegation is the least widely used technique. Loyalty is prized above all other organisational values, even efficiency. Loyalty can be guaranteed by surrounding the executive with subordinates whom he can trust. Arab managers have a more flexible interpretation of time than Western managers, and often seem able to run several meetings, perhaps on quite unrelated topics, simultaneously. The basic rule of business with Arab managers is to establish the relationship first and only come to the heart of the intended business at a later meeting, once trust has been achieved. This process may and often does take considerable time. Verbal contracts are absolute and an individual’s word is his bond. Failure to meet verbally agreed obligations may be visited with dire penalties and will certainly lead to a termination of a business relationship. None the less, the Arab world is essentially a trading world, governed by an implicit and extensive understanding of the requirements of commercial activity.

Al Faleh identifies the importance of status, position and seniority as more important than ability and performance. The central control of organisations corresponds to a low level of delegation. Decision-making is located in the upper reaches of the hierarchy, and authoritarian management styles predominate. Subordinates are deferential and obedient, especially in public in the presence of their hierarchical superiors. The consultation, which is widely practised, is done, however, on a one-to-one, rather than a team or group, basis. Decisions tend to emerge rather than to be located in a formal process of decision-making. Prior affiliation and existing obligation may be more influential than explicit performance objectives (Al Faleh 1987).

The formalities of social, family and political life are usually strictly preserved, even in managerial settings. Thus it is impossible to undertake any kind of meeting in an Arab organisation without the ubiquitous coffee or tea rituals. But the most significant cultural practices are those associated with the ‘Diwan’. This is a room with low seats around the walls found in one guise or other in every Arab home and most places of business, for it is a place of decision as well as of social intercourse. In the Diwan, decisions are the outcome of processes of information exchange, practised listening, questioning and the interpretation and confirmation of informal as well as formal meanings. Decisions of the Diwan are enacted by the senior people, but they are owned by all. This ensures commitment based on respect for both position and process. Seniority and effectiveness are significant, but to be powerful, the concurrent consent of those involved has to be sought, and symbolized in the process of the Diwan (see for a more detailed explanation Weir 2005c).

There are a growing number of studies which use standardized questionnaire methods and formal rating skills which claim to be culturally invariant, to study job satisfaction and organisational commitment. The results are difficult to interpret. Some studies report that Arab managers differ significantly in their commitment to their organisation compared to Western managers, while others find that expatriates and Arabs share similar work values.

Abbas Ali and his colleagues (1985) have undertaken several studies of the relationship between managerial decision styles and work satisfaction. They reinforce the general finding that Arab managers prefer consultative styles and are unhappy with delegation. They point, however, to the experience of political instability and to the growing fragmentation of traditional kinship structures as the origins of an ongoing conflict between authoritarian and consultative styles and the need for Arab managers to resolve this conflict by developing a pseudo-consultative style in order to create a supportive and cohesive environment among themselves.

They contrast Saudi-Arabian with North American managerial styles in that the Saudi managers use decision styles which are consultative rather than participative. Their value systems are ‘outer-directed’, tribalistic, conformist and socio-centric, compared to the ‘inner-directed’, egocentric, manipulative and existentialist perspectives of the North Americans.

Whereas American organisations are tall, relatively decentralized and characterized by clear relationships, Saudi organisations are flat, authority relationships are vague, but decision-making is centralized. In the USA, staffing and recruitment proceed on principles which are objective, based on comparability of standards, qualifications and experience. In Saudi organisations, selection is highly subjective, depending on personal contacts, nepotism, regionalism, and family name. Performance evaluation in Saudi is informal, with few systematic controls and established criteria, and the planning function is undeveloped and not highly regarded (Abbas Ali and Al Shakhis 1985).

Al Hashem and Najjar (1989) document the emergence of a managerial class in Bahrain in a series of publications which draw a picture of a well-educated and sophisticated cadre of professional managers, who may not be able to find the fulfilment that their Western counterparts would seek in their work, because of the tight constraints of organisational and administrative structures.

The values of Arab management

In reviewing all of these studies it has to be remembered that just as much as with studies of managers in other contexts we are dealing with a moving target. The Arab world is by no means static and business and industry are dynamic and motile social contexts. Thus to characterise in a summary way the values of management in the Arab Middle East is to risk the accusations of trivialization or of attempting to fix in stone only some selected aspects of what is clearly a fast-changing and dynamic reality. Adel Rasheed in a timely and well-taken critique of earlier attempts to characterise the ‘fourth paradigm’ has noted that parts of the paradigm are based on extensions and extrapolations of empirically-documented trends and may be subject to review and correction in the light of new empirical research. But this criticism, while true and fair, is an inevitable consequence of the attempt to formulate paradigms and ideal-types, to summarize the features that are established and to join the lines around areas that have not so far been researched.

So, this section by no means intends to portray these values of Arab management as ‘traditional’, fixed or unchanging. This is a very dynamic arena: many of these values are strongly contested, many of these positions no more permanent than would be claimed of other social representations and other manifestations of social consciousness in other regions.

Nor is it claimed that these values are unique and only to be encountered within this particular set of social groupings in this precise set of geographical locations. On the contrary, many are co-extensive with the field of management itself; modern management is no more or less contemporary in the Middle East than anywhere else, and managers no more or less diverse. Further in the context of the present discussions, it is not sure that all these elements are of equal interest to students of the ‘New Africa’. Some things are closer than others. But, it is pertinent and necessary to sketch in broad outline the description of something that yet with all these reservations and recognitions of inadequacy can be characterised as sui generis. We can identify several broad themes.

Firstly, the central significance of being Arab, sharing a common culture and consciousness of cultural difference in their core practice. Arab managers are conscious, sometimes pointedly so, that the generic depictions of the essential lineaments of ‘management’ and the ethical positions embodied in the Western ways of doing business do not fit their life-spaces at all points. Sometimes they may struggle, even apologise for the lack of fit but they know, deep down, that these clothes do not fit them. This may be equally true for the emerging self-consciousness of African managers.

In the Arab world and in particular within the Mediterranean basin, there is a decided ambiguity about notions of time ranging from ‘le p’tit quart d’heure Nicois’ which characterises business meetings in the Cote D’Azur to the ‘Boukara, Boukara Insha’allah’ (or in extreme cases to the ‘Boukara Fil Mishmish’ of the Northern Sahara). Boukara means tomorrow. Insha’allah means ‘if it is God’s will’. The mishmish or wild desert apricot rarely flowers so if a Bedouin claims that something may happen ‘Boukara fil mishmish’ you can be sure you have plenty of time in hand. Only one knows what will happen, and what will be will be. These are notions that disturb the Anglo-Saxon but fortify both the Arab and the Mediterranean consciousness. They are not unknown in sub-Saharan Africa.

The primary social institutions of the family and extended kin networks are seen as providing the necessary and sufficient frameworks for business and management activities. This assumption throws into special prominence the importance of networking as the master set of behaviours and skill-sets appropriate to managers. It also highlights the practices of ‘Wasta’ which are usually regarded as at least morally ambiguous if not downright corrupting to Western commentators.

Wasta can mean taking the role of a valued intermediary or a trusted middle-man. To say of a businessman that he has ‘good Wasta’ is to praise him for what Western writers call ‘network-brightness’. It may also imply that this is the person who acts as a gatekeeper or whose inter-mediation has to be rewarded. But while Arab managers are often quite critical of these practices, they clearly regard them as endemic to their culture and as unlikely to be affected by any form of ‘modernisation’. In the emerging patterns of management in China the persistence of Guanxi-based networking has some similar aspects (see Hutchings and Weir 2005).

Business and management are understood to be guided – as is all of social life- by higher laws or statements of value that do not derive from the practise of business itself. In principle as Rahman explains, ‘no real and effective boundaries were drawn between the moral and the strictly legal in Islamic law’ (Rahman 1966: 116). Thus the Shari’a embodies elements of codified juridical statements and exhortations that in other belief systems would be regarded as simply injunctions towards ethically desirable ends.

This is not held to be a consequence of the special subservience of business and management concerns to the dictates of religion or to the improbable views of religious leaders, but to be rooted in a common understanding that the end of business is not business and the goals of management are not defined within the constraints of particular structures of enterprise and public administration. This is in practice an enabling, rather than a constraining set of beliefs, and permits most formats of management activity: it prohibits merely the assumption that economic goals are inevitably predominant or that societies are merely economies writ large.

In Arab business dealings therefore, the ‘bottom line’ in short-term financial results is rarely, if ever, the bottom line. On the contrary, though business is an honoured profession and the prophet himself was a trader, there is no expectation that business goals ought in general to be those of society at large or that what is good for business is necessarily good for state and family. The over-arching criteria of business success derive from the creation and maintenance of community wealth rather than vice versa. These concepts of business as a force for general societal good seem to be quite compatible with social philosophies in many parts of Africa.

Changing trends

As educational standards rise, the emerging managerial cadres of the Middle World gain in confidence from the policies that steadily replace expatriate managers with nationals. This should reduce the pressures which managers experience in the perceived absence of opportunities for self-actualization at the workplace. But it may also produce a crisis of authority in the organisation.

These pressures are not dissimilar to those found in other cultures experiencing rapid social and economic change, an increasing globalisation of business and the emerging power of multinational enterprise, not least in the petrochemical industries. But the overarching philosophy and belief system of Islam, the essential cohesiveness of the family and tribal structures, and the sheer economic strength of the Arab states should allow the emerging managerial cadres the opportunity to find their own routes to organisational effectiveness.

Among topics on which further research is urgently needed is the question of women in management. Salman (1993) has documented the growing importance of women in the emerging managerial class in the occupied territories of Palestine.

Managers in the Arab world may have been too ready to criticise themselves, their organisational structures and their techniques of management and too reluctant to claim credit for the things that they do well and to enjoy doing them the way they prefer to do them. Arab managers often evidence an unwillingness to trumpet their organizational achievements. There are not many case studies in the business school literature of great Arab entrepreneurs or breakthrough Arab management techniques. More worryingly they may in their lack of confidence lose sight of the fact that, far from lagging behind the rest of the world, it is precisely in the relative strengths of the Arab way of management – in the performance of ‘the fourth paradigm’ – that an enduring comparative advantage may indeed lie.

The reasons for this optimism lie precisely in the social and organisational structures based on the integrating matrix of ethics and behaviour that we have noted earlier. Let us examine the likely dimensions of the emerging economic patterns of the twenty-first century. It is widely argued that the economy of the world is moving from an industry-based to an information-based format as we enter the ‘knowledge society’: large economies on the pattern of the former Soviet Union or even of the USA are not necessarily advantaged compared to the flexibilities, adaptiveness and fluidities of smaller economies. These may be based (in the opinion of one respected prophet of globalisation, the Japanese consultant Kenichi Ohmae) on the ‘city-region state’ rather than the ‘imperial’ or hegemonic model (Ohmae 1996).

In the ‘knowledge society’ there may be changes in enterprise structure from command organisations with their persistent and obstructive hierarchies in favour of smaller, networked organisations that provide a flexible and viable basis for sustained economic growth.

These models of business organisation are close to the familial models which are prevalent in the Arab world rather than on juridical composites linked by shareholder and stakeholder obligations. Family business is increasingly regarded not as a deviant or developmental phase in the evolution of corporate business organisations but as the fundamental source and well-spring of a balanced and dynamic economy. It already forms the basis of much business organisation in the Arab Middle East and is clearly highly relevant in Africa.

The same may be said of the newer technologies of information-based business structures, the ‘knowledge economy’. Knowledge economies depend on educated and trained entrepreneurs rather than on conformant management cadres. Centralist State control is not the obvious answer to creating social wealth through business activity, but neither, is the ethic of selfish individualism. Research in the growth poles of the European economy like the central Italian region of Emilia Romagna as well as in the Far East indicates that it is the common bonds of family, kinship, clan and tribe, naturally existing as potential bases for capital, skills and commitment, that provide the most reliable motor for sustained economic growth.

In the Middle World as a whole family is the basic element of society .Thus one writer says:

What could be called a truism in small town America is a fact in Saudi Arabia. Virtually every Saudi citizen is a member of an extended family, including siblings, parents and grandparents, cousins, aunts and uncles. The extended family is the single most important unit of Saudi society, playing a pivotal role not only in Saudi social life, but economic and political life as well. Even personal self-identity posits a collective self. Each family member shares a collective ancestry, a collective respect for elders, and a collective obligation and responsibility for the welfare of the other family members. It is to the extended family, not to the government, that a person first goes to seek help (Long 2003).

In Africa as a whole and in sub-Saharan Africa more especially it may be that these familial models of economic enterprise are especially relevant. Some scholars indeed have seen the extended family as the key organising principle of African economies. Decision-making follows different rules in the network economy of the Information Society to the imposition down the hierarchy of the strategic judgements of highly-paid executives remote from customers and suppliers on unwilling or ill-informed operatives. It is informed consent that will be required: perhaps it is the model of the family Diwaniah or Majlis, with its balance of consultative and autocratic phases that provides a better guide than the corporate boardroom to the ‘loose-tight’ properties of effective decision-making in this context.

Much attention has been recently paid to ‘de-coupled’ or ‘loose-coupled’ or ‘networked’ forms of business organisation and here again the advantages offered by the organisational bases of business in the Arab world are worth considering. Relations of trust between partners in loose-coupled structures are central to the outcomes of joint ventures: research in Turkey indicates that trust is indeed the central feature of successful joint ventures (Demirbag, Mirza and Weir 1996; 2003). Trust-based commercial organisations, guaranteed by intermediate social institutions of clan and family may have as much staying-power as those of the market.

Banking and the financial systems also need to adapt to the requirements of new forms of enterprise in identifying what it is they have to offer the global markets. This need not mean greed-based high-risk corporate strategies and financial manipulation; these may indeed have run their course in the West also. But the techniques of corporate recovery, portfolio-balancing and organisational support are not alien to the new generation of bankers in the region. Islamic models of financing for house purchase, assurance, and investment are compatible with sustainable enterprise growth. They may prove attractive models for Africa.

In the realm of culture much expenditure of senior management time and consultants’ ingenuity takes place in the West and in Japan to achieve what may come more naturally in economies where the key feature is precisely the existence of a common culture of practice rather than of precise doctrinal assent on minor matters. Central to this business culture are the understandings of good behaviour based on the indefeasibility of trust and the lack of incoherence between behaviour in one context and another that are features of Western business models and legal restriction. The notions of ‘limited liability’ and ‘risk’ alike operate in a quite different manner in societies of ‘shame’ and those of ‘guilt’.

The discourse of ‘management’ as internalised by many Arabs including the managers who have been trained in the West is inherently perceived by many as suffused with Western values and has yet to find a coherent representation in its own terms. So there are linguistic and philosophical minefields for both Arabs and Westerners to encounter in coming to a more precise and situated understanding of what it is that is characteristic and singular about management in the region, and what may be treated as ‘authentic’ experience.

Conclusion

This chapter has been quite wide-ranging but it has only scraped the surface of a complex reality. It may be helpful to summarize a few directions in headline format. We, in the West, know little about management in the Middle World and we should know more. There may be much to learn from it, perhaps especially for Africa. Management in this region is complex and multi-faceted but it is different in many ways from the Anglo-American or European models and does not conform either to the Eastern or Japanese models. It is a convenient short-hand to regard it therefore as constituting a ‘fourth paradigm’, despite the evident existence of behavioural and cultural diversity.

Islamic precepts and culture form the basic frameworks and elements of management in the region, but it is inadequate to characterise these aspects as constituting a ‘traditional’ or ‘conservative’ style of management. There are many dynamic and evolving aspects and the political and economic context is especially motile. Unless we understand the cultural configurations of Islam, our attempts to understand how managers in this world behave will be doomed to failure. Various elements of the ‘fourth paradigm’ indeed may be especially well adapted to the emergent needs of business in an increasingly global context, especially given the communications technology explosion.

There is no strong evidence of a comprehensive cultural convergence of the fourth paradigm with other paradigms or of the imminent Westernisation of these behaviours and beliefs. Per contra the Middle World obstinately continues on its own paths even when offered the seductive embrace of Western capitalism and democracy in one package complete with collateral damage.

Accordingly, the approaches to the management of people and in particular to such Western models as ‘human resource management’ and ‘human resource development’ must be very carefully handled when attempting to apply them holus-bolus to the practice of management in the Arab Middle East or to the dealings with the enterprises and organisations in this region.

It is perhaps in understanding the philosophical and ethical underpinnings of the styles of management and the practices of business that obtain in this region that much compatibility can be inferred with some of the implications of the ‘knowledge society’ and of ‘best practice’ in people management in the West and more generally. The learning from this exercise will not be only one way.

No conceptualisation of new patterns of Afrocentric management can be complete unless we incorporate an understanding of the Islamic-influenced aspects of management in the Middle World. Of all cultures that influence Africa, this remains one of the most profound, intense and deepest rooted. It is not part of the argument of this chapter to deal in detail with how and where these influences will work out. There may well be possibilities for confrontation between these models of economic behaviour and those of the largely Christian-influenced regions of sub-Saharan Africa.

In Nigeria plainly there is a real danger of such confrontations becoming a threat to existing political and economic structures. But just as both Western and Socialist blocs were ultimately disappointed in their attempts to see Africa as a relatively-available free-fire zone for their competing ideological struggle, so Africa will ultimately absorb such confrontations and emerge with a new cultural configuration that is neither absolutely one thing or another but contains elements of both.

A central feature of the growth of the economies of the Middle world in the past few decades has been the explosion of Islamic financial institutions. There is no reason to believe that these types of institutions cannot also flourish in the new Africa, for they appear to have several advantages over Western counterparts for developing economies based largely on family enterprises and supported by communal values.

Muslims need banking services as much as anyone and for many purposes: to finance new business ventures, to buy a house, to buy a car, to facilitate capital investment, to undertake trading activities, and to offer a safe place for savings. Muslims are not averse to legitimate profit as Islam encourages people to use money in legitimate ventures, not just to keep their funds idle.

A global network of Islamic banks, investment houses and other financial institutions based on the principles of Islamic finance has developed over the last three decades. Islamic banking has moved from a theoretical concept to embrace more than 100 banks operating in 40 countries with multi-billion dollar deposits world-wide. Islamic banking is widely regarded as the fastest growing sector in the Middle Eastern financial services market. From a zero base-line thirty years ago an estimated $US 70 billion worth of funds are now managed according to Shari’ah. Deposit assets held by Islamic banks were approximately $US5 billion in 1985 but grew to over $60 billion by 1994 and now stand at over $600 billion.

In specific terms, if present trends continue, Islamic banks will account for 40 per cent to 50 per cent of total savings of the Muslim population worldwide within 8 to 10 years. Islamic bonds are currently estimated at around US$30 billion and are the ‘hot issue’ in Islamic finance. There are around 270 Islamic banks worldwide with a market capitalisation in excess of US$13 billion. Deposit assets held by Islamic banks were approximately $US5 billion in 1985 but grew to over $60 billion by 1994. Today the assets of Islamic banks worldwide are estimated at more than US$265 billion and financial investments above US$400 billion. Islamic bank deposits are estimated at over US$202 billion worldwide with average growth between 10 and 20 per cent. Islamic equity fund are estimated at more than US$3.3 billion worldwide with growth of more than 25 per cent over seven years. The global Takaful premium is estimated at around US$2 billion. The Middle East market is reported growing at 15 to 20 per cent per year. Between 1994 and 2001, around 120 Islamic funds were launched. This is not a ‘traditional’ or a ‘legacy’ market. The emphasis in Islamic Banking on profit-and loss-sharing, on community wealth, and on family business may indeed have special appeal in the new Africa. There are few grounds for believing that the Western systems of finance and business are uniquely promising for developing economies whether in Africa, Asia or Latin America. One abiding characteristic of Islamic economic thinking is that it appears to provide a supportive philosophy enabling believers to deal equally validly with periods of wealth and poverty.

There are probably fewer grounds for believing that Africa must inevitably follow a Western path to economic development in the 21st century than there have been in the last three hundred years. We are dealing with a growing, evolving, dynamic entity, not a traditional hang-over from an ‘undeveloped’ past. And in that past, moreover, Islam was a dominant element. Arab traders from Oman were doing business in East Africa long before Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope; Leo the African, Hassan al Wazzan, ‘discovered’ Timbuctoo before Mungo Park, and he crossed the Sahara following the routes that the Touareg had known for generations.

Accordingly, it is very timely to consider the possibility that the future development of a culturally-appropriate and geo-politically relevant style of management in Africa may be based on Islamic principles, and be closer to those of the Middle World, than to those of Western Europe and North America or even of China. (Though there are interesting similarities between Chinese and Arab models of business networking. See Hutchings and Weir 2005.)

My prediction is that over the next few decades the influence of the emergent styles, including an authentically Islamic as well as secular versions of Arab-influenced management styles, not to exclude the multi-faceted ‘Mediterranean styles’, some of them owing much to the ‘Fourth Paradigm’ will become increasingly significant in the world in general and possibly in Africa in particular and the Diwan will come to be seen as equally as important as the derivative.

But much more research attention and much more theoretical sophistication is required of management theorists, and undoubtedly a diminished reliance on dated characterizations and inapt cultural categorization based only on Western experience. This paper is, hopefully, a contribution to that understanding.

References

Abu-Doleh, J. and Weir, D.T.H. (1997) Management training and development needs analysis: practices in Jordanian private companies, Middle East Business Review, 2: 1.

Abuznaid, S. (1994) Islam and management, Proceedings of the second Arab Management Conference, University of Bradford Management Centre.

Ahmed, A.S. (1993) Living Islam, London: Penguin Books.

Ali, A.J. (2005) Islamic perspectives on management and organisation, London: Edward Elgar.

Ali, A. and Al-Shakhis, M. (1985) Managerial value systems for working in Saudi Arabia: An empirical investigation, Group and Organisation Studies, 10: 135-51.

Al-Janahi, A. and Weir, D.T.H. (2005) How Islamic Banks deal with problem business situations: Prospects for Islamic banking as a model for emerging markets, Thunderbird International review on Emerging Markets and International Business, Special Issue.

Al-Janahi, A. and Weir, D.T.H. (2004) Alternative financial rationalities in the management of corporate failure, Managerial Finance, 32(4).

Al-Rasheed, A.M. (1994) Traditional Arab management: Evidence from empirical comparative research, Proceedings of the second Arab Management Conference, University of Bradford Management Centre.

Attiyyah, Hamid S. (1991) Effectiveness of management training in Arab countries, Journal of Management Development, 10(7): 22-9.

Alwani, M. and Weir, D.T.H. (1993, 1994, 1995,1996, 1997) Proceedings of the first, second, third, fourth and fifth Arab Management Conferences, University of Bradford Management Centre.

Bin Laden, O. (2005) Messages to the world, London: Verso.

Chenoufi, B. and Weir, D.T.H. (2000) Management in Algeria, in M. Warner (Ed.), Management in emerging countries: Regional encyclopedia of business and management, London: Business Press/Thomson Learning.

Cunningham, R.B. and Sarayrah, Y.K. (1993) Wasta: The hidden force in Middle Eastern society, Westport, CT: Praeger.

The Economist (1998) Saudi Arabia: A forecast, the world in 1999, London: Economist

Publications, p. 81.

Dadfar, H. (1993) In search of Arab management, direction and identity, Proceedings of the first Arab Management Conference, University of Bradford Management Centre.

Demirbag, M., Mirza, H. and Weir, D.T.H. (1995) The dynamics of manufacturing joint ventures in Turkey and the role of industrial groups, Management International Review, special issue, 35(1): 35-52.

Demirbag, M. and Mirza, H. (2000) Factors affecting international joint venture success: An empirical analysis of foreign-local partner relationships and performance in joint ventures in Turkey, International Business Review, 9(1): 1-35.

Demirbag, M. and Mirza, H. (1996) Inter-partner reliance, exchange of resources and partners’ influence on joint venture’s strategy, Bradford: University of Bradford, Management Centre, Asia Pacific Research and Development Unit Discussion Paper Series.

Demirbag, M. and Iseri, A. (1999) Overcoming stereotyping: Beyond the cultural approach, Middle East Business Review, 3(1): 1-21.

Demirbag, M. (1994) The dynamics of foreign-local joint venture formation and performance in Turkey, PhD Thesis, Bradford University, Management Centre.

Demirbag, M., Mirza, H. and Weir, D.T.H (2003) Measuring trust, inter-partner conflict and joint venture performance, Journal of Transnational Management Development.

Eliot, T.S.(1944) Four quartets, London: Faber and Faber.

Hickson, D. and Pugh, D. (1995) The Arabs of the Middle East, Management Worldwide, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Hofstede, G. (1991) Cultures and organisations, software of the mind, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. (2005) http://www.geert-hofstede.com/.

Hutchings, K. and Weir, D.T.H. (2005) Cultural embeddedness and contextual constraints:

Knowledge-sharing in Chinese and Arab countries, Thunderbird International Review, special Issue on The silk road, Fall. Islamic Finance Forum: http://www.iiff.com/

Jabr, H. and Amawi, S.T. (1993) Financial management in Islam, Proceedings of first Arab Management Conference, University of Bradford Management Centre.

Lewis, B. (2002) What went wrong?, Atlantic Monthly.

Long, D.E. (2003) The role of the extended family in Saudi Arabia, Newsletter, Saudi-American Forum.

Mangaliso, M. (2001) Building competitive advantage from ubuntu: Management lessons from South Africa/executive commentary, The Academy of Management Executive, available at: http://www.lexis.com/research.

Medhat, A. (1997) TQM in a major Saudi Organisation, PhD thesis, Bradford University.

Mubarak, A. (1998) Motivation in Islamic and Western management philosophy, PhD thesis, Bradford University.

Muna, F.M. (1980) The Arab executive, New York: Macmillan.

Muna, F.M. (1989) The making of Gulf managers, MEIRC Consultants.

Nahas, F.V., Ritchie, J.B., Dyer, W.G. and Nakashian, S. (1995) The international dynamics of Palestinian family business, Proceedings of third Arab Management Conference, University of Bradford Management Centre.

Ohmae, K. (1996) The end of the nation state: The rise of regional economies, London: Harper Collins.

Peristiany, J.G. (1966) Honour and shame: The values of Mediterranean society, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rahman, F. (1966) Islam, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ramadan, T. (2001) Islam, the West and the challenges of modernity, Markfield: The Islamic Foundation.

Sabri, H. (1995) Cultures and structures: The Structure of work organisation across different cultures, Bradford: University of Bradford Management Centre.

Salman, H. (1993) Palestinian women and economic and social development in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, UNCTAD/DSD/SEU miscellaneous papers, no. 4.

Sharabi, H. (1988) Neo-patriarchy: A theory of distorted change, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shubber, K. (2000) Our economics: A translation of Iqtisaduna, London: Muhammad Baqir Al-Sadr Book Extra.

Sulieman, M. (1984) Senior managers in Iraqi society: their background and attitudes, unpublished PhD thesis, University of Glasgow.

Tayeb, M. (1995) The global business environment, London: Sage Publications.

Weir, D.T.H. (1998) The fourth paradigm, in A.A. Shamali and J. Denton (Eds), Management in the Middle East, Kuwait: Gulf Management Centre.

Weir, D.T.H. (2000a) Management in the Arab world, in M. Warner (Ed.) Management in emerging countries, Regional Encyclopedia of Business and Management, London: Business Press/ Thomson Learning.

Weir, D.T.H. (2003) Human resource development in the Arab world, in M. Lee (Ed.), Human resource development in a complex world, London: Taylor and Francis.

Weir, D.T.H. (2005a) Some sociological, philosophical and ethical underpinnings of an Islamic Management model, Journal of Management, Philosophy and Spirituality, 1(2).

Weir, D.T.H. (2005b) The Arab as the ‘dangerous other’? Beyond Orientalism, paper presented to CMS4 Critical Management Studies conference, track on post-colonialism, Cambridge: Cambridge University

Weir, D.T.H. (2005c) The Diwan, a spatial basis for decision-making, paper presented at the APROS (Asia-Pacific Research in Organisation Studies Conference), Melbourne: Victoria University.

Younis, T. (1993) An overview of contemporary administrative problems and practices in the Arab world, Proceedings of the first Arab Management Conference, University of Bradford Management Centre.