Reshaping Remembrance ~ Glorious Gables

2 Comments Introduction

Introduction

The correctness of the term ‘Cape Dutch architecture’ has often been questioned, but a better and clearer one has never been agreed upon. Museum director Dr. Jan van der Meulen, in a doctoral thesis at a German university in the sixties, tried to prove that it should rather be called Cape German. As a result he was often referred to as ‘doktor Von der Moilen’.

The ‘Dutch’ of the term was probably introduced by English speakers and must have referred to ‘the architecture of the Dutch period’ rather than suggesting a ‘Dutch’ stylistic origin. Such an origin – apart from a certain German influence, if you wish – can certainly be detected in certain details, like gable design and door and window types, but is not at issue in our context. The Cape was Dutch, and not German. And if there are two things that characterize early Cape colonial architecture (if we must use an alternative term), it must be its highly recognizable quality and its strong homogeneity. Within a few decades the little settlement at the Cape developed a domestic architecture that has an unmistakeably local character, of which the highly uniform elements persisted for over a century and a half – well into the British period, in places well into the second half of the nineteenth century. There may well be similarities with domestic architecture in parts of Europe, but no Cape farmstead or townhouse can be mistaken for anything similar over there, not even in the Netherlands or its other former colonies.

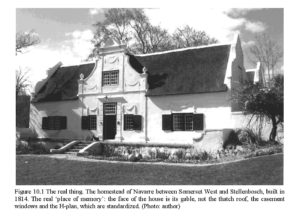

Due to this high degree of uniformity (the causes of which are discussed further on) it is comparatively easy to describe the main elements of this style. These are, first of all, its standardized plan forms and, secondly, the decorative ‘overlay’, notably the gable. The gable is often regarded as the outstanding feature of Cape Dutch architecture. But this is not entirely correct. A Cape farmhouse without a centre gable (and there are hundreds of them) is still undeniably Cape Dutch. But without what we call the ‘letter-of-the-alphabet’ plan it certainly is not. But granted: where ‘places of memory’ – iconic features – are discussed, the chances are we are referring to the Cape gable. Let us therefore first get the development of the unique wing-type plan formation out of the way, while being aware that, while it is this that makes a building ‘Cape Dutch’, in itself it never became a ‘place of memory’.

The homestead of Navarre between Somerset West and Stellenbosch, built in 1814. The real ‘place of memory’: the face of the house is its gable, not the thatch roof, the casement windows and the H-plan, which are standardized.

Standardization

Right across North-Western Europe – Jutland, Schleswig-Holstein, Holland, Flanders, but elsewhere, too – it is not unusual for farmhouses to show an elongated, shed-like form, sometimes with living and working areas onder one and the same roof. But these can be of varying width and roof height. In the Cape colony, on the other hand, farmsteads but also village dwellings from an early stage developed a standardized form with a uniform width and roof span of just over six metres. Initially they were simple rows of rooms, that could be extended as more rooms were required. In order for such a ‘train’ – as one or two of such long rows of rooms are in fact known locally – ‘letter-of the-alphabet’ (also called ‘dominoes’) plans were developed. The T-plan had a kitchen wing extending from the front room towards the back. When even this plan did not provide enough space, two more wings could be added sideways to the ‘tail’, yielding the celebrated H-shaped plan – for all intents a classy double-deep, block-shaped house, with two façades but covered by two parallel roofs with narrow open side courts. In 1825, the traveller Marten Douwes Teenstra saw near Caledon what was clearly an Hhouse being built, and expressed his surprise at what he thought were ‘two separate houses’ that the farmers built for themselves.[i] There were also U-shaped farmhouses with two ‘tails’ (particularly in the Cape Peninsula), and houses shaped like a small ‘h’ or the letter ‘pi’.

As we saw, all these plan forms, and also the elongated outbuildings (sheds, wine ‘cellars’ etc.), had a width and a roof span of about six metres in common, about five metres inside width allowing for spacious, multi-purpose rooms. Such standardization of ground-plans is unknown anywhere else in the Western world or the colonies. How did it originate? There is something undeniably deliberate and rational about this aspect of what in other respects is a true vernacular building mode, an ‘architecture without architects’, as Bernard Rudofsky called it in his epochmaking exhibition in the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1964.

It is tempting to ascribe this standardization to an advice or perhaps even an instruction from the side of the East India Company, early during the existence of the little colony. Could it have been issued by commissioner-general Hendrik Adriaan van Reede tot Drakestein, who called at the Cape in 1685 in order to inspect and regulate the settlement in several areas? Van Reede had acquired a great deal of administrative and practical experience in other colonies, and was a widely respected scientist. At the Cape, he played an important role in the foundation of the town of Stellenbosch, intended to impose some secular and religious control in the outlying districts, and it is known that he felt strongly about proper accommodation of the colonists.

It is likely that it was Van Reede who advised to apply standardization, with uniform roof trusses and standard lengths of beams and floor-boards.The resulting way of building – apart from the pleasing proportions of wall-to-roof and of fenestration it produced – enabled simple village builders to erect sturdy and dignified abodes without the help of skilled architects, and it survived for a full century and a half or more. It could even be used in the erection of churches (Tulbagh) and drostdy buildings (Swellendam). In the small towns that started to emerge the style also produced a highly harmonious streetscape.

Indeed, it is this plan-form that became the essential feature of Cape Dutch architecture. But this unique way of building never produced ‘places of memory’. Nobody in later years would erect a building with thatched-roof wings of six metres width in order to serve an iconic function, as status symbol or to inspire national pride. For one thing, it would look far too modest to impress!

The gable

Although it may not be the essential feature of Cape architecture, its ‘face’ is characterized by what is in fact no more than an addition, as a cherry on the top: the gable. From the beginning, it must have been meant as a sort of icon, as a feature that distinguished the homestead of a proud farmer from that of his neighbour, and in more recent times, too, was used to revive some of that identity, even if mostly out of context.

Politically correct cultural historians have interpreted the six gables of an H-shaped homestead radiating their presence to the front, the sides and the back, as a symbol of the ‘conquest of the land’. All the more so, then, for the Rhodes-remake of Groote Schuur, which boasts double that number of (‘revival’) gables!

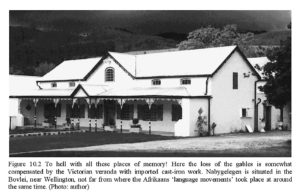

Figure 10.2 To hell with all these places of memory! Here the loss of the gables is somewhat compensated by the Victorian veranda with imported cast-iron work. Nabygelegen is situated in the Bovlei, near Wellington, not far from where the Afrikaans ‘language movements’ took place at around the same time. (Photo: author)

In essence, a gable is a very common and simple architectural detail. The word gable or ‘gewel’ is probably related to the Dutch word ‘gaffel’ which refers to the forked pole that supports the roof ridge of a primitive Medieval house. It denotes the upper part of an end wall that contains the roof-end and rises above it slightly. In the towns and cities of North-Western Europe, where houses usually face the street with their narrow ends, there are literally thousands of gables. (In the Netherlands, the word ‘gevel’ now refers to the entire façade, and the upper part is a ‘topgevel’.) These triangular, sloping features lend themselves perfectly for decorative enrichment: bell-gables, ‘neck’ gables, etc., which in their design closely mirror the current art-historical styles.

But these are all ‘end gables’. What distinguishes our Cape farmsteads and townhouses – which without exception face sideways – are not their end -gables but their centre gables. Strictly speaking centre gables are not gables at all, but could be called ‘fullheight flush dormers’. In North-Western Europe such gables are not unknown but, like the domino plan, they are nowhere – not even in former colonial areas – the general feature they became at the Cape. Our Cape houses, in rural areas, in towns, and even in the streets of Cape Town before the advent of double-storey houses in the late eighteenth century, always faced the approach or the street with their long side. Such long and perhaps slightly monotonous façades with their rows of sash or casement windows called out for an accent in its centre, above the entrance. Precisely when this became common practice is not certain. It is unlikely that frivolities like gables were part of Van Reede’s instructions. The oldest dated gable that has been preserved is that of Joostenberg, dated 1756, and although this is already a fully fledged ‘Baroque’ concave-convex gable, there cannot have been been many such gables from before that date, or else at least a few of them would have been preserved.

Joostenberg was indeed the beginning of the ‘golden age’ of gable building as a feature, but it was preceded by simpler, part-height dormers, as Stade’s panoramas of Cape Town and Stellenbosch show as early as 1710. European stylistic trends were not immediately followed, but show a delay of a few decades, exactly as could be expected.

The Baroque and Rococo styles produced more and more curvilinear shapes, from Meerlust (1776) to the elaborate design of Vredenburg (1789). After that, Neo-classicm made its appearance, with its more rectilinear designs, pilasters and pediments, yielding masterpieces such as Nektar (1819) and Navarre (1815, fig. 1). The gable of Lanzerac (1830) shows that the gable style had lost none of its beauty and dignity by that time. After that, however, it started to lose its vigour, although in towns such as Worcester, Robertson and Montagu it remained in use until the late 1880s.

It was the advent of a new industrially produced building material, corrugated iron, that spelled the end of the gable style. It is striking that the descendants of the people of the Cape who developed the style as part of their architectural identity, displayed so little respect for the gables as that heritage.

Travelling salesmen talked owner after owner into replacing their thatch roofs with the new material. It is true that corrugated iron presents less of a fire hazard and is more durable, needs a lesser slope and therefore allows for higher walls and loft spaces with small windows. But it also required the clipping of gables in order for the roofing sheets to rest on the walls. This did not unduly worry many owners and hundreds of the finest gables unceremoniously bit the dust.

The gable revival

It is ironic that, while descendants of the gable builders were busy destroying their heritage, the style experienced a large-scale revival at the hands of English-speaking people. This could partly be ascribed to the fact that in England the upheavals of the industrial revolution had taken place half a century earlier and had given rise to a culture of veneration for pre-industrial monuments, also in the colonies. At the initiative of aesthetes like William Morris and John Ruskin, the Arts and Crafts Movement was founded, and the Society for the Preservation of Historic Buildings and the National Trust all endeavoured to study and protect what was perceived as the simple beauty and honest crafsmanship of pre-industrial architecture.

The Cape Afrikaners, on the other hand, welcomed with open arms the first, belated signs of the industrial era. The Cape had to wait for the restoration of Groot Constantias after the fire of 1925 (by the architect F.K. Kendall) for a preservation ethic to be established. Even among the Afrikaans language activists of the late nineteenth century, the ‘taalbewegings’ (language movements), the ‘Genootskap van Regte Afrikaners’ (Brotherhood of True Afrikaners), and in Die Patriot and early editions of Die Brandwag and Die Huisgenoot, there is little evidence of an interest in traditional architecture. There is an interesting parallel here with the way in which the Brown people of the Cape show so little interest in their old mission towns like Mamre or Genadendal, so much admired by tourists for their ‘picturesqueness’ – presumably because it reminds the villagers of a time from which they want to move away.

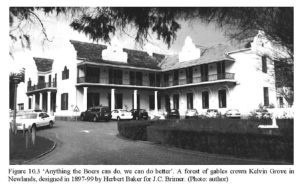

Figure 10.3 ‘Anything the Boers can do, we can do better’. A forest of gables crown Kelvin Grove in Newlands, designed in 1897-99 by Herbert Baker for J.C. Brimer. (Photo: author)

But while the actual conservation of the Cape Dutch heritage itself had hardly been contemplated at the beginning of the twentieth century, its ‘revival’ had already begun in earnest. Its great ‘pioneer’, the architect Herbert Baker, was well acquainted with the British Arts and Crafts Movement and particularly with the highly eclectic Queen Anne style, and therefore had a predilection for historic architectural styles. This does not mean, however, that he had a sound understanding of the Cape vernacular and could do justice to it in his own designs. Baker did have a sympathetic patron in the person of Cecil Rhodes, who in 1893 commissioned him to remodel his own property Groote Schuur and in doing so to make abundant use of ‘Old Dutch’ elements to satisfy his own romantic ‘Arts and Craft’ ideals – for which Rhodes had initially shown more understanding than Baker. The end result shows little similarity to any of the earlier appearances of the ‘Barn’, not even the attractive, dignified late-Georgian form prior to Baker’s remodelling. Gables there are in great numbers, of the most elaborate design of course, as well as details like small-pane windows with shutters that are not really meant to shut, barley-sugar chimneys, semicircular upper-storey windows as well as the large relief on the centre gable, none of which really succeeded in recalling the folk style. It was also far from ‘Barbaric’, as Rhodes said Baker could make it.

Baker expressed his intentions as follows:

The charm of the Cape Dutch homesteads lies much more in their larger qualities than in their picturesque detail. The fact cannot be too much emphasized as a warning to imitators that unless they understand and work in the spirit of the old builders, they will assuredly fail to advance and establish this or any other style in South Africa. We hear much nowadays of an original South African style. It will never be achieved through copying and imitating borrowed detail, but only through impersonal subordination to the larger ideals and conception of architecture.[ii]

Although it took Baker sixteen years to demonstrate any true understanding of the ideals expressed here, and during that time very little evidence can be found of the ‘spirit of the old builders’ in his work, one can only agree with the fine sentiments he expressed.

Apart from the (badly understood) admiration for the ‘larger qualities’ of Cape architecture, what was exactly the real intention of its (flawed) use at the hands of Rhodes and Baker and of all the dozens of prominent fellow English-speakers? After Unification in 1910, there was a noticeable tendency towards the creation and protection of a South African cultural heritage that was to encourage the development of a national pride. A kind of patronage of old Cape architecture was part of this, even to the point of becoming a status symbol among the English patriciate, including among the mining ‘Randlords’ up North. It was one of the latter, Sir Lionel Phillips, encouraged by his wife Florrie, a Colesberg girl, who in 1917 bought the old farm Vergelegen and had it restored. Rhodes himself bought up fruit farms here and there, preferably with old homesteads on them.

The application, seldom very successful, of Cape Dutch stylistic elements, long remained the work of English patrons and architects.

Kelvin Grove in Newlands was built by Herbert Baker for one J.C. Rimer and was so richly provided with revival elements – not all typical of the Cape: wainscoting, decorative fireplaces – that the end result could hardly be called a tribute to the local vernacular. In 1905, Baker built the imposing villa Rust-en-Vrede in Muizenberg, this time for Rhodes’s friend Abe Bailey. Despite an excess of gables, the architect here managed to remain somewhat closer to the folk style. It was perhaps only at Welgelegen in Mowbray that he really succeeded in capturing some of the old style they all admired so much – perhaps only because much had remained of the original building.

It may count in Baker’s favour that his best architectural creation in this country, the Union Buildings in Pretoria, owes in its general design little to the traditional style. But it is also significant that the main initiators of this building were the Afrikaner leaders Louis Botha and Jannie Smuts, who clearly saw no need to use mock gables for the purpose of nation building.

However, the eclectic Cape Dutch revival style long remained in use by Englishspeakers, perhaps also as a sign of goodwill towards their Afrikaans compatriots – especially after the end of the Anglo-Boer War. For several decades there is little evidence of a genuine interest by Afrikaners themselves. Even the first serious studies published on the subject had to come from English authors: Alys Fane Trotter,[iii] Dorothea Fairbrisdge,[iv] F.K. Kendall, G.E. Pearse.[v] Their work was continued by De Bosdari, Mary Cook and James Walton.

Inspiration for national pride

The most absurd use of the gable style as ’places of memory’ is that which occurred in Kwazulu-Natal during the ‘thirties, when the painter Gwelo Goodman was commissioned to embellish the headquarters of the Tongaat sugar plant with bad copies of well-known Cape Dutch buildings, or new designs in the old style, both for their offices and workers dwellings. It was much appreciated by members of the Natal ‘sugarocracy’, and used with gusto – and obviously out of context. Perhaps its use there can be seen as a case of cultural appropriation more than of real admiration. The first signs of an awareness of the potential of the Cape Dutch style to inspire a national pride appeared in the thirties and are undoubtedly related to the advent of Afrikaner nationalism. The official residences of both the Transvaal administrator and the prime minister simply had to reflect the Cape style. It is true that for Overvaal (1937) the design had to be entrusted to one V.S. Rees-Poole: a neat building with good copies of Cape windows and a curvilean gable over the centre of its two-storey façade – something unknown in the Cape vernacular.

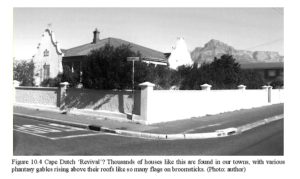

Figure 10.4 Cape Dutch ‘Revival’? Thousands of houses like this are found in our towns, with various phantasy gables rising above their roofs like so many flags on broomsticks. (Photo: author)

But for the design of Libertas (1940) at last an Afrikaans architect was found when Gerard Moerdijk (admittedly the son of a Dutch immigrant!) won a competition out of fifty participants, and produced a well-proportioned flat-roofed double-storey. A similar recipe was used for the Stellenbposch city hall (1941, the work of ‘captain’ Elsworth and Walgate), perhaps slightly more ‘correct’ than Libertas, but frankly boring and hardly inspiring.

Were Overvaal and Libertas successful as ‘places of memory’? The most powerful such icon in the country is surely the Voortrekker Monument (1938-49), the work of the same Gerard Moerdijk. Here, the architect managed to create a contemporary sort of Art Deco design of near-fascist dimensions and symbolism that surely succeeds much better, without resorting to thematic references to the old Cape such as little gables or small-paned windows – thanks also to ample funding!

Conclusion

Literally thousands of little gables can be found gracing the end walls of projecting stoepkamers of town houses from the 1920sand 1930s, with decoratively shaped parapets along the sloping roof line.

They might be very remote descendants of Meerlust or Joostenberg, but they are hardly ‘symbols of national pride’. The ‘Cape’ centre gable remains a popular motif in our more affluent suburbs, often monstrosities on structures that owe little or nothing to traditional plan forms, often featuring sash windows with shutters that are screwed to the wall.

Today it is generally accepted that the Cape Dutch heritage, or what survives of it, should qualify for preservation and where necessary for careful restoration. Authoritative studies have been undertaken, inventories compiled, books written. Expert architects are available. Finances often present a problem, which can result in the creation of modern wine-tasting facilities and even Disneyland features where entire farmyards are turned into hotels and entertainment facilities. The existing conservation agencies do not always have the power to control this sort of development.

But that the traditional Cape Dutch homestead, and more in particular the Cape gable, was and still is a significant icon, a ‘place of memory’, is certain. It was always intended in the first place, perhaps not to fulfil an iconic role a quarter millennium later, but certainly to lend a recognizable identity to an authentic rural style of architecture peculiar to a settlement in a far-flung corner of the world, and to individual dwellings in their own right. That the style, and its gables, managed to do this so well is a tribute to these pieces of masonry and plasterwork by nameless plasterers. Who they were exactlymay never be known. It is often maintained, politically correctly, that they were slaves, or coloured craftsmen, and this may well be the case. It cannot be denied however that the designs are genuinely European, and not Oriental in origin. It is all the more striking, therefore, that the very communities who created them, later cared so little for them and left it to another nation to give them an iconic status.

NOTES

i. M.D. Teenstra, De vrughten mijner werkzaamheden, gedurende mijne reize over de Kaap de Goede Hoop naar Java. Cape Town: Van Riebeeck-Vereniging 1943.

ii. H. Baker, ‘The architectural needs of South Africa’, in: The State (1909), 512-525.

iii. A.F. Trotter, Old colonial houses of the Cape of Good Hope. London: Batsford 1900.

iv. D. Fairbridge, Historic houses of South Africa. London: Oxford University Press 1922.

v. G.F. Pearse, Eighteenth century architecture in South Africa. London: Batsford 1933.

References

Atwell, M. & Bergmann, A. ‘Arts and crafts and Baker’s Cape style’. In: Architecture SA, July/August 1992.

Baker, H. ‘The architectural needs of South Africa’, in: The State (1909), 512-525.

Christensen, E. ‘Herbert Baker, the Union buildings and the politics of architectural patronage’, in: SA Journal of Art and Architectural History 6 (1996), 1–9.

Cook, M.A. ‘Some notes on the origin and dating of Cape gables’, in: Africana Notes and News 4 (March 1947).

Fairbridge, D. Historic houses of South Africa. London: Oxford University Press 1922.

Fairbridge, D. Historic farms of South Africa. Cape Town: Maskew Miller 1931.

Greig, D. Herbert Baker in South Africa. New York: Purnell 1970.

Greig, D. A guide to architecture in South Africa. Cape Town: H. Timmins 1971.

Johnson, B.A. Domestic architecture at the Cape 1892-1912: Herbert Baker, his assistants and his contemporaries. Doctoral thesis, University of South Africa 1997.

Keith, M. Herbert Baker, architecture and idealism, 1892-1913. The South African years. Gibraltar: Ashanti 1992.

Merrington, P. ‘Cape Dutch Tongaat: A Case Study in “Heritage”’, in: Journal of Southern African Studies 32 (2006), 683-699.

Pearse, G.F. Eighteenth century architecture in South Africa. London: Batsford 1933.

Teenstra, M.D. De vrughten mijner werkzaamheden, gedurende mijne reize over de Kaap de Goede Hoop naar Java. Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society 1943.

Trotter, A.F. Old colonial houses of the Cape of Good Hope. London: Batsford 1900.

Van der Meulen, J. Die europäische Grundlage der Kolonialarchitektur am Kap der Guten Hoffnung. Doctoral thesis, Marburg/Lahn 1962.

Walton, J. Homesteads and villages of the Cape. Pretoria: Van Schaik 1952.

Watson, R.G.T. & Drennan, A.R. Garbled gables: A note on the use and misuse of Cape Dutch architecture. Durban: Coronation Brick and Tile Co. 1953.

You May Also Like

Comments

2 Responses to “Reshaping Remembrance ~ Glorious Gables”

Leave a Reply

May 22nd, 2019 @ 11:32 am

Very interesting and a good read! When was Glorious Gables by Hans Fransen published?

May 24th, 2019 @ 7:46 am

The paper was forst published in: published in: Albert Grundlingh & Siegfried Huigen (Eds.) – Reshaping Remembrance. Critical Essays on Afrikaans Places of Memory – Rozenberg Publishers 2011 – Savusa Series 3 – ISBN 978 90 3610 230 8 – Editing: Sabine Plantevin.