Reshaping Remembrance ~ Thandi, Katrina, Meisie, Maria, ou-Johanna, Christina, ou-Lina, Jane And Cecilia

Dit was dus ons gesin; maar daar was ook nog ou Dulsie, van wie ek amper vergeet het, soos mens maar geneig is om van die bediendes te vergeet, alhoewel sy by ons was so lank soos wat ek kan onthou. […] daardie gedurige aanwesigheid waaraan ek skaars nog name of gesigte kan koppel. Dulsie in die huis […] so onthou ek my kinderjare.

Dit was dus ons gesin; maar daar was ook nog ou Dulsie, van wie ek amper vergeet het, soos mens maar geneig is om van die bediendes te vergeet, alhoewel sy by ons was so lank soos wat ek kan onthou. […] daardie gedurige aanwesigheid waaraan ek skaars nog name of gesigte kan koppel. Dulsie in die huis […] so onthou ek my kinderjare.

[That was our family; but then there was also old Dulcie, whom I almost forgot to mention, as people tend to do with servants, although she was with us for as long as I can remember. […] that pervasive presence to which I can hardly put a name or a face. Dulcie in the house […] that is how I remember my childhood years.][i]

1.

Many women’s names were never used in the contact zones of South African kitchens. Together with their small caps and aprons, black women working in white South African households were often given new names that were easier for white people to pronounce than, for example, Noluvyo, Nokubonga or Nomahobe. These ama-Xhosa names mean Joy, Thank you God and Dove. Sometimes black parents took the initiative and named their children Beauty, Patience or Perseverance, in the hope that their daughters would meet with success in the white working environment. Sometimes employers themselves gave ‘well-known’ names to their servants, and I suspect that most of the names in the title of this chapter belonged to this category. All of these women, from Thandi to Cecilia Magadlela are women who have been important in my life for no other reason than that I was fortunate enough to belong to the class which employed these women as servants.

As Richard Elphick writes in Kraal and castle: Khoikoi and the founding of white South Africa,[ii] it was customary, right from the start, for young indigenous women to be trained to work as serving maids in white households at the Dutch settlement of the Cape. Once slavery began, they were increasingly replaced by women from East India who had greater culinary and household skills. The real name of one of the first South African women to work in a white household in the Cape was Krotoa (approximately 1642-1674). This Khoi-woman of the Goringhaiqua group was called Eva by Jan van Riebeeck and his wife. Thanks to the novels of Dalene Matthee and Dan Sleigh, among others, many post-apartheid South Africans know that, aside from being a maid servant, she was also Van Riebeeck’s most important interpreter who, through her marriage to a Danish ship’s doctor, also became the ancestor of quite a number of white families. No one could have anticipated that, three hundred and fifty years later, a maid bearing the same name would become a much loved cartoon character. However, this Eve would no longer be referred to as a childminder or ‘maid’, but as a ‘domestic maintenance assistant’ and would be given a ‘western’ first name – probably because of its combination with Madam, a play on Adam – but also a surname: Sisulu. In most of these sharp, witty Madam & Eve cartoons, she has the last word. All the characters in this cartoon have become icons in a changing South Africa where, although equality is still a distant dream, the way Eve triumphs is transformative despite the stereotypical roles that are played out.

The concept of Eve and her Madam was born when the American Stephen Francis went to visit his mother-in-law in Alberton, Gauteng, with his South African wife whom he had met in New York in 1988. The dynamic between this housewife and her servant Grace fascinated him: ‘the yelling and complaining of both parties sparked an idea in my mind’, he was to recount later.[iii] Shortly after this, he joined two South African pioneers of satire, the historian Harry Dugmore and the artist Rico Schacherl. A few years later the million-dollar title of Madam & Eve was launched and it has appeared every day since 1992 in The Weekly Mail (now the Mail & Guardian). On the Internet, Eve is introduced as ‘a sassy individual’:

She has lived and suffered under the harsh rule of Apartheid and as a result has faced the many difficulties of having to be a live-in maid to a bored and affluent white woman. Pitiful wages and indifference towards her are just two of the many injustices Eve faces. Yet she tackles her employer and the world with a sassy fervour.[iv]

She is not afraid of lying on the ironing board and, when asked indignantly by her ‘Madam’ whether she thinks this is a holiday, of saying that she has joined ‘M.A.D.A.M.’: ‘Maids Against Doing Anything On Monday’. She is constantly devising entrepreneurial schemes with her friend, the ‘Mealie Lady’, who can be seen every day walking through Johannesburg’s suburbs with a bag of mealies (corn) on her head to sell to the locals. In April 2004, Eve and her friend organised the ‘Secret Domestic House Party’ and ‘The Mealie Lady Party’ to celebrate the tenth anniversary of their acquiring the right to vote – which finally marked the access of these black working-class women to political democracy. Eve is still a housemaid, but the way in which she stands up for her rights and always has the last word makes her a symbol of freedom and hope. To use the words of Achille Mbembe in an interview on his book On the postcolony (2001): ‘As far as Africa is concerned, colonialism is over. Apartheid is over too. Africans are now the free masters of their own destiny’. This naturally does not mean, as he adds, that freedom is easy. ‘The work of freedom is very risky […] because it involves a transformative relation with our past as a condition sine qua non of our control over our own future’.[v]

2.

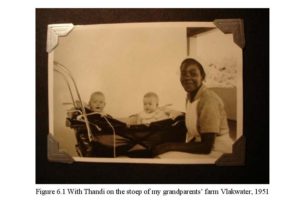

I, a white child, was born three years after the National Party came to power. In my childhood photo albums there are few, but nonetheless some, pictures of black women. Some are wearing white caps, others kopdoeke, headscarves. Most of them are wearing white aprons. The first photo is on the twelfth page of the first of two photo albums which I inherited from my Boland (Western Cape) grandmother Tibbie Myburgh-Broeksma (1901-1988). She and my Oupa lived in Darling. The photo was taken in October 1951 at ‘Vlakwater’, my father’s family farm near Viljoenskroon. My sister and I were seven months old. We are sitting on the edge of either side of our twin-pram on a wide veranda. Next to us sits a young black woman with cap and apron, looking friendly and happy. Whether she was a Free State ousie (maid) or whether she rode with us and the pram on the back seat of my parent’s first motorcar, Jan Groentjie, from Colenso in Natal, my father’s first parish, I don’t know.

The small black and white photo is, like all the others, attached with little silver corners to the black pages of the album with its green cover and lacing along the spine. On almost every page there are captions in white ink. I still remember the crown pens which my grandmother and my mother used to write in the albums. Between each page there is a light cellophone sheet of paper (did we used to refer to them as tracing paper?). Now that I look more closely at the album, I notice for the first time that these see-through pages must have been added by my ouma: neatly cut by hand and each one attached with a thin line of glue to the fold in between the pages. With each page my sister and I grow bigger. Captions say ‘Proud mother’, ‘Too lovely’, ‘Proud father’, ‘Look at the two of us!’, ‘We start to crawl’, ‘Ena and her tooth’, ‘We see our 6 a.m. bottles’, ‘Christine standing’. We gnaw chicken bones, clamber over my father on the sitting room carpet, sit on either knee of Ouma Darling and then again on Ouma Plaas’s lap. ‘What Father Christmas brought us’ shows us with wide, toothy smiles, sitting once again in our pram. Set out for the camera, surely by my father who always wanted everything tidily in a row: two little elephants, two balls, two wooden wheelbarrows each with a Father Christmas, and, the best kept for last, two gigantic teddy bears. I remember – I suspect the bears lasted a long time – just how soft those large ears were, but if you continued to stroke and probe them you could feel the unmistakable wire frame inside. These soft bears were a present from Oupa and Ouma Darling.

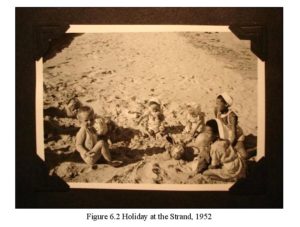

It was they who, shortly before we were born, gave our lovely young mother a Kodak camera for her 21st birthday so that they, more than a thousand miles away, could follow her and their only grandchildren growing up in faraway Natal. In one of the photos ‘mevroutjie’ (little Mrs), as the parish called her, sits in a real coach with the words ‘Durban. Jan van Riebeeck Festival 1952’ painted on it. In preparation for the countrywide folk festival, the coach also travelled through our small Natal midlands town. We crawl, laugh, bathe and begin to walk. We spend our first birthday at the Strand (‘How wonderful it is by the sea!’). On the same page that the words ‘1st Birthday’ and ‘Ena’s first steps’ are written is a photo with the caption ‘Mon Desir 6 April 1952’. We are sitting on our grandparents’ laps. On the 300th anniversary of the settlement of the whites at the Cape, the oldest and youngest members of our family are captured on camera. The day was therefore consciously experienced as a ‘Kodak moment’, worthy of being remembered and documented. In two of the other holiday photos three unfamiliar children are with us on the beach. Also two young brown girls with white caps and aprons, hardly ten years old I would think. They also have buckets and spades within easy reach, but they sit upright, slightly vigilant, watching us sitting at the edge of the dry white sand close to the darker line of wet sand.

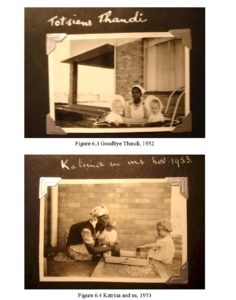

Some pages further on, at the age of 16 months, we are involved in other kinds of activities. We are being trundled around the bare rectory garden by my father (beyond the garden is just open veld), in another photo we are laughing happily with a young black man pushing us, we sit on wicker chairs wearing our mother’s hats on our heads with our arms folded and, then with sun hats back in our pram. The caption of the pram photo is ‘Goodbye Thandi’.

It is without doubt the same pram, and the same woman we saw sitting on the farm photo alongside us. She was our own Natal Thandi who had come to the Free State with us. Now she is squatting behind us and looking into the camera lens with the same lovely, happy gaze. What she is going to do and why we have to say goodbye to her is not clear from this cryptic caption.

Our life without Thandi continues in album number two. There is a hailstorm, my father’s first ever rose bush in his first ever garden is in flower (‘Phew it smells good!’), we are picnicking at Cathedral Peak, sitting with mugs, rolls and meat balls on rocks at the source of the Tugela River. My father is building us a swing and a dovecote for himself, we are again visiting Vlakwater, sitting on a horse together with our Uncle Hendrik, visiting the ‘Zoo’ in Pretoria. On the same page as ‘Christmas 1954’ there is a photo of ‘Katrina and us Nov. 1953’.

Another young black woman is kneeling next to us as we stack wooden play blocks into a box on the ground near the corner of our house. She is wearing a headscarf and ‘ordinary’ clothes. In March 1954 Katrina is standing with us together with another black woman, perhaps a friend from ‘next door’ (she is wearing a cap and a white apron on which is embroidered a basket of flowers). Above our heads young, green creepers climb over a pergola. My sister and I are both trying to get a small black child (the daughter of Katrina or her friend?), who does not even reach our three-year old shoulders, to hold our hands. On another photo on this page, it is two weeks later and our birthday. There is a group photo of about fifteen children at our party (in a row, naturally). The small black child is not there.

A number of photos of Katrina were stuck in the album in June 1954. She is with us as we ‘drive’ the upside down wheelbarrow with my sister steering the large wheel between her knees. On another photo we sit leaning up against Katrina on a low wall; we are looking up at her, all three laughing happily. Do my clearest childhood memories date back to this period? I remember one afternoon seeing Katrina running out of the long grass next to our house – from the path cutting diagonally across the open plot of land from the town side. I see what I think are thick streaks of reddish-brown polish on her arms. Suddenly I realise that it is blood. What could have happened to her? I don’t know. At around the same time I remember that there was some travelling salesman who turned up at our doorstep and that he shot dead an iguana which appeared out of nowhere, probably also from the long grass.

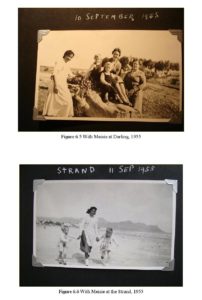

A number of pages further on, September 1955, we are again visiting our grandparents in Darling. Their house was on the furthest edge of the town. Mon Desir, the house in which my grandpa lived as Manager of Standard Bank, still stands today; in Nerina Street – unrestored and apparently forgotten and therefore precisely as it was in those days with its high round veranda, old-fashioned outbuildings and garden gates on three sides. A desirable place once again. It was there that my sister and I had ‘our tree stump’, in the open, sandy veld full of Namaqualand daisies, some twenty metres from the garden. We always played there. It was an enormous sawn-off blue gum tree, with slender offshoot branches on the one side which we put to enthusiastic use as reins. Our whole family was able to sit on it for the photo: my ouma (then 55 years old), my mother (who was to turn 25 three days later) and us (2 x 4 years of age). My oupa (with his high Myburgh forehead, jacket and tie – having certainly just returned home from the bank) stands behind all of us. The photo was taken on 10 September, the same day that I sit writing this, 52 years later, older than my Ouma was then. Alongside us stands a coloured woman with a happy laugh.

Meisie was her name, dressed in ordinary clothes, wearing an apron. One day later, on 11 September, we are running along the Strand holding Meisie’s hands. She is wearing black shoes and white socks. So are we. On the photo you can see Hangklip and Gordons Bay in the background, with the curved line of the mountain road. On another photo, my mother is posing with her youthful body in her bathing suit with our hands in hers, the Melkbaai Private Hotel with its light art deco curves behind us: a two storey building with a wide veranda on the ground floor and a broad balcony on the first floor, and on the right-hand side yet another extra storey. The Melkbaai double storey standing high with melkbos (Euphorbia), holiday homes and False Bay all around it.

That is where the albums I inherited from my grandmother end. Included among the family photos are those without any family members – a parade of horse riders, some carriages, flag bearers on a show ground with the inscription ‘Day of the Covenant 16 Dec. 1955 P.M.B’. Perhaps this was the inauguration of the Church of the Covenant in Pietermaritzburg where my father went to? I do not have any other albums with me in Amsterdam. I have to rely on my memory. Is it less ‘true’ than the album? If nothing else, an archive, even in the form of a family photo album, always creates the illusion that it is possible to retrace ‘the truth about the past’. Just how selective the photo album as archive can be is clear, especially when we consider how expensive analogue films and the printing of photos were in those times. First Thandi, then Katrina, even Meisie during our Cape holidays, probably spent hours with us during the day, but you would never suspect this as you page through the albums. That there are in fact so many traces of them in our family archive is quite unusual – also that they went on so many outings with us.

3.

Michel Foucault radically changed our ideas about the archive in 1970 and 1972 when he pointed out that the archive was not simply the sum of texts which a particular culture wished to remember and deemed worth their while to record and protect. Nor does it represent in any simplistic way the institutions which gave instructions for their recording and protection. Archives in the sense used by Foucault and postcolonial theorists, such as Anne Stoler, speak to the imagination because they continue to call for interpretation, for translating configurations of power. The archive is a metaphor for the desire and longing which characterise the search for a hypothetical ‘truth’ and for an imaginary ‘origin’. To understand this you only have to read Reconfiguring the Archive.[vi] The archive is a system of inclusion and exclusion, of laws and rules which give shape to what may and may not be said and heard. So-called factual accounts make it possible for a nation to maintain its fictions; the range of philanthropic missions can be worked out in moralistic tales, but selection and manipulation always play a part. There is no trace in our photo albums of what my South African Party grandfather and grandmother may have thought about the terrible injustice done to Meisie and other brown people when they were removed from the voters’ roll. In one way or another, they too, in those albums, helped to build a history of our growing up, which at that time became irretrievably more nationalistic, more exclusive and structurally increasingly white.

What Thandi and Katrina actually did to help us as we grew up, I don’t know. I wish that I could remember if they bathed us. Like old Melitie bathed Alie. But at the same time I also know that we did not grow up on a farm and that neither of them was old Melitie. How I harbour such after-the-event wishful thinking has everything to do with Alba Bouwer’s Stories van Rivierplaas (Stories of a River Farm); a book we grew up with, partly because Aunt Alba was my father’s second cousin and partly because this so-called River Farm was one of Vlakwater’s neighbouring farms. Many children grew up with an idealised but ambivalent image of Old Melitie with her ‘blue chintz dress which swirled around her’ and her bracelets which jangled ‘tring-a-ling’ in the friendly Free State farm kitchen, where she was portrayed as Alie’s rock and anchor. Despite the fact that Alie’s father believed she was old enough to wash her own feet at night, no white (child) reader would, until quite recently, have found it odd for Old Melitie, who had two children of her own at home, to be asked to continue to wash Alie’s feet when Aunt Lenie says: ‘Oh, Father, if Old Melitie does it, we can all finish up more quickly at night’.[vii] ‘All’ of course refers only to the white people on the farm. Throughout the four pages of wonderful narration of the interaction between Alie the dawdler and the caring old servant, the reader is never once tempted to give a passing thought to the fact that Old Melitie herself needs to get home. Only once Alie’s entire body has been washed and Old Melitie says: ‘Pakisa, nonwe Alie. Now you must take care to wash your face’, can Old Melitie leave. Then Old Melitie wraps her black shawl with its long fringe around her shoulders, takes the small flat box of snuff from where she keeps it tucked away in her headscarf and says: ‘goodnight, baas Jaan, goodnight, nonwe Alie,’ and with the swaying of her blue chintz dress casting shadows in the firelight, crosses the threshold into the night. ‘She passes through the squeaking farmyard gate towards the huts in the valley on the other side of the dam.’[viii] Twice it is emphasised that she is ‘swallowed up by the dark night’[ix] – naturally to re-appear the next day before daybreak. The portrayal of this feudal labour relationship is never questioned from Old Melitie’s perspective. What could be more wonderful than a white child’s memory of the solicitude described by Alba Bouwer?

In yet another family archive, my father’s autobiography Weerklank van tagtig jaar 1924-2004 (Reflections on eighty years, 1924-2004)[x], he describes our family’s fouryear stay in the Northern Natal town of Utrecht, from 1957 to 1961 – a period of my childhood which I remember well and with great happiness. In the book there is a photo of ‘Our loyal helpers in Utrecht: Johanna, Jim en Maria.’ We ‘inherited’ them from the family of the previous pastor, and everyone lived in the yard in their own outside rooms in various parts of the enormous town plot. Old Johanna was a stout, silent woman who always wore a headscarf and did most of the ironing. I remember her getting cross with us once when we wanted to throw grasshoppers into the Aga stove on which her black iron stood sizzling. Old Jim was the gardener who in his day had killed a vulture with his knopkierie when he was lying in the veld sleeping off a dagga binge and was thought to be a potential prey. Maria was young and pretty, with her white cap and apron. Without anyone realising that she was pregnant, she gave birth to her first baby one night. I well remember how we stormed into her room in great excitement, somewhere to the left of the large garage, her bed raised on bricks, and a strange little string tied around the baby’s waist.

4.

In 1961, we were ten years old and our family moved to the city. My father was often out of town. In the days of the Mau-Mau, Uhuru and rumours about Mandela, Rivonia and internal uprisings, it was considered safer for us not to live in a house. My mother taught her speech and drama classes in a hall near our school. We caught the bus and, for the first time in our lives, often came home to a mother-less house. Fortunately Christina, a cheerful vision in pink uniform and cap, waited for us at home. Somewhere behind the row of garages of the apartment building were rooms in which some of the servants stayed. I never saw any of these rooms. I am also not sure whether our city Zulu maid Christina also stayed there and only disappeared into Kwa-Mashu township on week-ends after which she sometimes returned too late on a Monday morning to help with breakfast. Exactly why she left, I don’t know. I remember only one successor, Margaret, and after that no-one specific. We never had a full-time maid after her. We went to high school, washed our own school shirts and polished our shoes. Not for us the pampered and trusting relationship between child and servant as that which emerges from the following dialogue between Alie and Old Melitie when she has to go to Ruyswyck School:

‘Jo, nonwetjie Alie,’ Old Melitie said, ‘your little dress will be de prettiest one at dat school, and de shirt too, they’re alles new. Who gonna iron your little shirt when you far away? Will you tink about me?’

‘Old Melitie,’ said Alie, ‘I’ll think of you every day when I put on a new shirt, and everyday I will wish for winter so that I can come back home and tell you about everything.’[xi]

Rather moving to be sure, but naturally this depiction of a paternalistic ’loving’ relation does not necessarily produce a ’progressive’ text, but has more the effect of entrenching social roles.

As our family embarked on its ‘servantless’ life in Durban in the sixties, an interesting article appeared in the Lantern, a bilingual Afrikaans/English journal, called the Journal of Knowledge and Culture, published by the Institute for Education, Science and Technology in Pretoria: ‘The Servantless House’.[xii] It was seven pages long, richly illustrated with line drawings of functional open-plan kitchens and clean work surfaces. T.W. Scott, who was, according to a footnote, a research officer of the ‘National Building Research Institute’ of the ‘Council for Scientific and Industrial Research’ in Pretoria, illustrated by means of tables and statistics that ‘influx-control’-legislation, industrial expansion, the decreasing gap between wages for skilled and unskilled labour and the minimum industrial wage would lead to fewer and fewer white households being able to afford servants. ‘The influx-control of Bantu women will only become effective now that the carrying of reference books has become compulsory. As the majority of domestic servants are Bantu women, it is likely that the influence of influxcontrol is now to be experienced properly for the first time.’[xiii]

In the fifties, despite pass laws, it was still relatively easy for black women to live illegally in cities. This also meant that they were easy to exploit. From the sixties onwards, people employing these illegals were fined R500 and were obviously less willing to employ black women ’without papers’. The fact that Lantern published an article on the servantless household in 1964 was surely not coincidental. According to Scott, ‘an overview of household expenditure in November 1955 showed that an average of 0.83 full-time black servants worked for white families and received an average monthly salary of R9.62’. 1955 was also the year in which Minnie Postma’s collection of stories Ek en my bediende [My Maid and I], illustrated by Katrine Harries,[xiv] was published. Further ‘entertaining sketches’ followed in Alweer my bediende [More about My Maid].[xv] Scott adds that the average maid’s salary in 1964 had increased by approximately 38 per cent, which meant that the 0,83 full-time maid per household who may have continued to work would by then have earned R11.00 per month. Salaries in Cape Town were always the highest in the country. In 1955 a Cape maid (0.54 per household – interestingly enough this figure was lower in 1941: 0.48) received an average of R14.10 (in 1941 R5.26), whereas Durban maids (1,08 per household – in 1941 this figure was 0.98) only earned R7.26 (in 1941 monthly R3.73). Food and lodging were often also provided. Scott cites as the main reasons for white households having to do with fewer maids after 1955 and certainly after 1964, even though he does not provide any statistics, the westernisation of the ‘Bantu’ and ‘the growing tendency for Bantu servants to live in their own townships’.

As proper family housing is being made available in the townships the tendency is a natural one. The process may be further hastened by legislation to limit the number of domestic servants housed in the White residential areas. Sociologically, this development is probably desirable, but its immediate effect will be to increase wages if they are to cover travelling expenses. At the same time the number of hours worked is likely to decrease and this will in effect increase the wage rate from the employer’s point of view.[xvi]

He showed that the size of stands in South Africa had, until then, been largely determined by history and the tradition of black domestic workers. ‘They have an outbuilding section separated from the main structure, usually comprising a garage, servant’s room, and servant’s toilet-cum-shower’.[xvii] The disappearance of full-time ‘sleep-in’ servants was to have massive consequences for house design after 1964.

With no servant in the house, some of the need for internal separation of the areas for the sake of privacy will be reduced. This will make possible more informal and open planning with more direct communication between rooms. For example, there need be no strong demarcation between the living area, dining area, and kitchen. […] In South Africa kitchens are usually unnecessarily large because the housewife does not like being in a very confined space with a servant. . […] When the servant goes, we shall need surface finishes in the house that are easily cleaned and maintained. Floor finishes are by far the most important. […] Wall-to-wall carpeting will no doubt become very popular because of the ease with which it can be maintained.[xviii]

He urged whites to buy expensive but labour-saving electrical goods; the servantless house would, he estimated, save the owners the monthly sum of R21.80. The modern age could be met head on. At the same time braaivleis [barbecue] became an increasingly South African ‘tradition’ – every man was now boss of his backyard. The servant’s room became part of the double garage.

5.

Many people of my generation knew as we were growing up that the adult black people on the periphery of our lives were often humiliated, unhappy and ‘long-faced’. We saw their nervousness when they came to the back door with their passbooks. We saw the impatient powerlessness of our parents, the extension of a demonic regulating power from who knows where; noted how they had to check and sign those creased little books. Anne McClintock, in her sharp analysis of The Long Journey of Poppie Nongena (1978)[xix], described the legislation as follows:

In 1964, in an act of inexpressible cruelty, amendments were made to the Urban Areas and Bantu Labor Act, which made it virtually impossible for a woman to qualify for the right to remain in an urban area. Wives and daughters of male residents were now no longer permitted to stay unless they too were legally working. F.S. Steyn, member for Kempton Park, put the matter bluntly: ‘We do not want the Bantu woman here simply as an adjunct to the procreative capacity of the Bantu population.’ It became a life of running to hide. Nongena and other women hide under beds or in lavatories and wardrobes, or take cover in the bushes until the police have gone.[xx]

How little was actually known about these women. Poppie was the exception: she is one of the most articulate voices of black women in Afrikaans literature. In a moving orchestration of ‘oral history’-interviews by Elsa Joubert, Poppie is given a highly audible voice through the novelist’s sophisticated and unmistakable mediation. Because Poppie Nongena is such an important book in South Africa’s social and literary apartheid context, Poppie’s powerlessness and dependence on the power of the passbook administrators, but also on white women, is still remembered by many readers even today.

If one is to believe Minnie Postma’s light-hearted maids stories, there was a lot of interaction in South Africa’s large kitchens, and far more life histories could have been recorded. Few white women, who had this amazing opportunity to record and narrate the ‘unstoried’ experiences of black women, actually did so. Everyday the domestic worker contributed to maintaining the culture of the clean house and the myth of civilisation that went with it, but every evening she would have to return to her room in the back garden, often without lights or hot water. The ambivalent role of servants lay in the fact that there was both an intimate relation between the housewife and the domestic worker, sometimes even a secret attraction between baas or son and the servant, but this intimacy was always located in an extremely dangerous and prohibited sphere. In the end, politics and the physical distance between the house and the servant’s room were maintained not only out of a conviction of family morality but above all through the iron laws administered from Pretoria. No other being was as involved in the private spaces of the white family, but there were countless written and unwritten rules which governed this interaction. Her mug and plate were always underneath the sink, she was always alone or with the children on the back seat, even if there was place for her next to the driver, especially if it was the ‘baas’ who was driving who might have had to drop her off at the station or in town.

The same ambivalence governed the representation of servants in South African literature: despite their constant presence over decades, servants were almost invisible and inaudible. In the incomplete, fragmented and even ghostliness of the archives, many women disappeared down the passages or out of the back door. Like Dulcie in Karel Schoeman’s novel. This is not a uniquely South African experience. Maid servants play a generally subordinate role in all literature, as slave, sometimes even as sex symbol, as in Simon Vestdijk’s Dutch novels where the young Anton Wachter associates the smell of beeswax floor polish with bunched up skirts and erotic impulses. Antoinette Burton shows that Indian novelists who belonged to the elite and had servants, wrote almost nothing about them:

(W)e can see, if only by glimpsing, what their architectural imagination lost down the corridor of years as well as what it captured – with servants’ lives the most dramatic and perhaps paradigmatic example of what can never be fully recovered.[xxi]

Their presence was so obvious that nothing was said about it. Like the household furniture, they are presented as part of the family’s possessions. Burton quite rightly observes that the textual silence around servants is proof of the silence and violence of all archives.

In novel after novel one has to go in search of these women, investigate what this silence means. What is the history of the representation of women who are triply repressed? How did writers, like Postma and Bouwer, make the identity formation of white families possible and unconsciously convey to generations of white children that they were the bearers of a dominant order of whiteness; how did they instil them with the notion that they had the right to service and authority? Alison Light, in her brilliant book Mrs Woolf & the Servants: The Hidden Heart of Domestic Service,[xxii] recently wrote the kind of book that needs to be written in South Africa. The one I would like to write. I would like to read all South African novels in search of women with maid’s caps and doeke who stood in the hearts of the kitchens, who walked down the passages and who are fast disappearing out of the back door of our memories.

Acknowledgement

The photos originate from two photo albums (34 x 26 cm). The dark green album contains photos from 1951 to March 1953 and the dark red album dates from June 1953 to March, 11th 1956. The Cape photographs were probably mostly taken by my grandfather P.G. Myburgh (1900-1973) and those made in Natal and the Free State by my father J.C. Jansen (born 1924).

NOTES

i. K. Schoeman, Hierdie lewe. Kaapstad: Human & Rousseau 1994, 26-28.

ii. R. Elphick, Kraal and Castle. Khoikoi and the founding of white South Africa. Londen: New Haven 1977, 177, 205.

iii. http://www.megweb.uct.ac.za/www/students/madameve.co.za

iv. Derived from http://www.megweb.uct.ac.za/www/students/madameve/evcart1.htm (downloaded April 2004).

v. Hoeller, ‘Interview with Achille Mbembe’, 2002, http://www.stanford.edu/~mayadodd/mbembe.htm (1 April 2004).

vi. C. Hamilton et al, Reconfiguring the archive. Kaapstad: David Philip 2002.

vii. A. Bouwer, Alba Bouwer-Omnibus. Kaapstad: Tafelberg 1995, 15.

viii. Ibid, 4.

ix. Ibid, 20.

x. J.C. Jansen, Weerklank van tagtig jaar 1924-2004. ‘n Outobiografie. Published by the author 2004. From this chronicle it is clear that, despite my father’s own small salary, our servants where paid well compared to the average amounts for servant salaries mentioned by T.W. Scott (T.W. Scott, ‘The servantless house’, in: Lantern. Tydskrif vir kennis en kultuur (Desember 1964), 59-65).

xi. A. Bouwer, Alba Bouwer-Omnibus. Kaapstad: Tafelberg 1995, 203.

xii. T.W. Scott, ‘The servantless house’, in: Lantern. Tydskrif vir kennis en kultuur, December 1964, 59-65.

xiii. T.W. Scott, ‘The servantless house’, in: Lantern. Tydskrif vir kennis en kultuur, Desember 1964, 62.

xiv. M. Postma, Ek en my bediende. Kaapstad: A.A. Balkema 1955.

xv. M. Postma, Alweer my bediende. Pretoria: Van Schaik 1959.

xvi. T.W. Scott, ‘The servantless house’, in: Lantern. Tydskrif vir kennis en kultuur, Desember 1964, 61.

xvii. Ibid, 62.

xviii. T.W. Scott, ‘The servantless house’, in: Lantern. Tydskrif vir kennis en kultuur, Desember 1964, 62.

xix. E. Joubert, Die swerfjare van Poppie Nongena. Kaapstad: Tafelberg 1978.

xx. A. McClintock, Imperial leather. Race, gender and sexuality in the colonial context. New York: Routledge 1995, 325.

xxi. A. Burton, Dwelling in the archive. Women writing house, home and history in late colonial India. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2003, 144.

xxii. A. Light, Mrs Woolf & the servants: The hidden heart of domestic service. London: Fig tree 2007.

References

Barrett, Jane Vukani Makhoisikazi: South African Women Speak. London: Catholic Institute for International Relations 1985.

Bouwer, Alba Alba Bouwer-Omnibus. Kaapstad: Tafelberg 1995.

Burton, Antoinette Dwelling in the Archive. Women writing house, home and history in Late Colonial India. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2003.

Cock, Jacklyn Maids and Madams. A Study in the Politics of Exploitation. Johannesburg: Ravan Press 1980.

Elphick, Richard Kraal and Castle. Khoikhoi and the founding of white South Africa. London: New Haven 1977.

Francis, S., H. & Rico Madam & Eve’s greatest hits. Penguin Books 1997 [online: http://www.madamandeve.co.za].

Jansen, Ena ‘Eva, wat sê hulle?’ Konstruksies van Krotoa in Suid-Afrikaanse tekste. Amsterdam: Vossiuspers Univeristeit van Amsterdam 2003

[online: http://dare/uva.nl/ document/11001].

Jansen, Ena ‘Krotoa alias Eva. Van VOC-document tot stripfiguur’. In: Van Kempen, Michiel et al. (red.). Wandelaar onder de palmen. Opstellen over koloniale en postkoloniale literatuur en cultuur. Leiden: KITLV Uitgeverij 2004, 363-377.

Jansen, Ena ‘“Ek het maar net saam met die miesies gebly.” Die representasie van vrouebediendes in die Suid-Afrikaanse letterkunde: ’n steekproef’. In: Stilet, 17:1 (March 2005), 102-133.

Joubert, Elsa Die swerfjare van Poppie Nongena. Kaapstad: Tafelberg 1978.

Light, Alison Mrs Woolf & the Servants: The Hidden Heart of Domestic Service. London: Fig tree 2007.

McClintock, Anne Imperial leather. Race, gender and sexuality in the colonial context. New York/ London: Routledge 1995.

Mdladlana, M.M.S. Domestic workers and their employers. Basic conditions of Employment Act. Act 75 of 1997. Pretoria: APCOR Publications 2002.

Postma, Minnie Ek en my bediende. Kaapstad/Amsterdam: A.A. Balkema 1955.

Postma, Minnie Alweer my bediendes. Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik 1959.

Schoeman, Karel. Hierdie lewe. Kaapstad: Human & Rousseau 1994.

Scott, T.W. ‘The Servantless House’. In: Lantern. Journal of Knowledge and Culture (December 1964), 59-65.

Van Niekerk, Marlene Agaat. Kaapstad: Tafelberg 2004.

Yawitch, J. The Relation between African Female Employment and Influx Control in South Africa, 1959-1983. University of the Witwatersrand, Unpublished MA Dissertation 1984.