Reshaping Remembrance ~ The ‘Volksmoeder’: A Figurine As Figurehead

The ‘Volksmoeder’ is the Afrikaans manifestation of the universal Mother of the Nation phenomenon. In South Africa she cuts a fine, statuesque figure; she is a figurehead, a figure of speech, an idealised figure of womanhood as well as a petite bronze figurine. During the course of the twentieth century this figurine became a figurehead which marshalled Afrikaner women and girls to commit themselves in the service of their families and their ‘volk’ – a nation in the making. With this call to arms, the Volksmoeder was appropriated as an evocative and emotionally laden site of memory to which several generations of Afrikaner women readily responded.

The ‘Volksmoeder’ is the Afrikaans manifestation of the universal Mother of the Nation phenomenon. In South Africa she cuts a fine, statuesque figure; she is a figurehead, a figure of speech, an idealised figure of womanhood as well as a petite bronze figurine. During the course of the twentieth century this figurine became a figurehead which marshalled Afrikaner women and girls to commit themselves in the service of their families and their ‘volk’ – a nation in the making. With this call to arms, the Volksmoeder was appropriated as an evocative and emotionally laden site of memory to which several generations of Afrikaner women readily responded.

As a site of memory, the bronze figurine of the Volksmoeder still carries her years well even now in the early 21st century. One of about twenty copies of the Afrikaans sculptor Anton van Wouw’s 1907 figurine ‘Nointjie van die Onderveld, Transvaal, Rustenburg, sijn distrikt’ (Maiden from the Upcountry, Transvaal, Rustenburg district) has found a home on my bookshelf. This little Volksmoeder – rather a petite girl – has a round face, a fine, sharp little nose, downcast eyes, a tiny mouth and a somewhat cheeky fringe escaping from her bonnet. Her small shoulders are pulled downwards under the weight of her shawl and her hands are neatly clasped in front of her. At barely 40cm she resembles a fourteenth century Virgin Mary, with eyes submissively downcast, waiting pensively, patiently, politely and passively to be dusted. She is the visual shorthand of the ‘nobility and the beauty of the young Afrikaans girl which should inspire many to simplicity and greater spirituality’.[i]

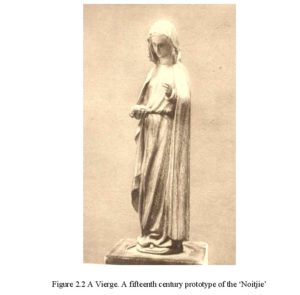

Figure 2.1 A Boervrou. The ‘Noitjie’ as she was used as logo of the Afrikaans women’s magazine Die Boervrou

Between 1919 and 1932, this figurine became the trademark of the first successful and widely read Afrikaans women’s magazine Die Boerevrou, and a symbol of the idealised Afrikaner woman and of national motherhood.[ii] The motto of the magazine, an extract from a poem by the Afrikaans writer Jan F.E. Celliers – which goes, ‘I see her triumph, for her name is – Wife and Mother’, complemented the visual message that the figure was fragile yet strong, and could and would emerge triumphant in the face of adversity.

Seen against the background of the trauma of the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902), of the great loss of life of women and children, as well as of the material destruction of the rural areas, Celliers’ triumphant woman makes sense. Women needed the encouragement and reassurance that they would be able to overcome the dire post-war conditions.

Like Celliers, his poetic counterpart, Van Wouw was intimately involved in the postwar project of visualising the Volksmoeders as ultimate victors in the struggle for life and survival. In a vein similar to his figurine’s, Van Wouw’s 1913 majestic group of three women in bronze at the Women’s Memorial in Bloemfontein, commemorating the suffering of women and children during the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902), depicts Afrikaans women as patient and long-suffering Volksmoeders. Larger than life, elevated on a podium at the base of a sandstone obelisk, they transcend the death and suffering commemorated by the Memorial. They survey the landscape and the future, fully conscious of their assigned calling to struggle on behalf of the nation. Rather than remaining victims of war, women’s dignity and worth needed to be restored by portraying them as heroines who made great sacrifices at the altar of the nation. In this manner, an attempt was made to deal with the trauma of war and the huge loss of civilian life, especially that of children.[iii] The Boer woman needed to be reassured that despite the grievous loss of her children she remained a good wife and mother, and that indeed she was the mother of the future nation. The Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurverenigings (Federation of Afrikaans Cultural Organisations (FAK)) contended:

‘Despite the humiliation, the wretchedness and suffering, she keeps her head held high as if she sees the unseen – the resurrection of her nation’.[iv] During the first half of the twentieth century the Volksmoeder became an important component in the propaganda arsenal of Afrikaner nationalism. The formal description – her verbal image – appeared just after the Afrikaner Rebellion (1914) and the end of the First World War (1914-1918). In 1918, the women of the Free State Helpmekaar Kultuur Vereniging, (Free State Mutual Aid and Cultural Society) commissioned Dr Willem Postma (aka ‘Dr Okulis’ – Oculis) to write a book Die Boervrou, Moeder van haar Volk (The Boer Woman – Mother of her Nation). His description of the Volksmoeder is closely correlated with the visual representation of both the figurine and the bronze composition at the Women’s Memorial in Bloemfontein. He echoes the need to provide reassurance and positive reinforcement to the Boer woman:

We need not feel shame for the Boer woman. We have every reason to honour and love her. No better, more noble mother than the Mother of the Boer Nation has in a more complete and richer sense ever nurtured a nation. Her history, her life is beauteous, pure, honest and dignified.[v]

Dr Okulis devotes a chapter to the ‘Character of the Boer Woman’ in which he describes in detail her sense of religion and of freedom, her virtue, self-reliance, selflessness, her housewifeliness and her inspirational role. She has noble and enviable qualities. She is brave, friendly, a hard worker, honest, hospitable, frugal, peace-loving and content with her destiny in life.

Shortly after the appearance of Postma’s book, Eric Stockenström’s book Die Vrou in die Geskiedenis van die Hollands Afrikaanse Volk (The Woman in the History of the Dutch-Afrikaans Nation) appeared. It is a concise yet ambitious history of Dutch-Afrikaans women from 1568 to 1918. Stockenström imbues the Volksmoeder with similar character traits as Dr Okulis, such as housewifeliness, virtue and inspiration. According to Stockenström even the Voortrekker women of the 1838 Great Trek fully appreciated their calling as Volksmoeders, and in time they became the mothers of the future Afrikaner nation. Both writers devote much attention to the women’s role in the Great Trek; especially the threat of Susanna Smit, the formidable wife of the Voortrekker pastor, Erasmus Smit, that she would cross the Drakensberg bare-foot rather than submit to British rule. Yet both men avoid discussing the suffering of women during the Anglo-Boer War. The trauma of ‘onse oorlog van onuitwisbare heugenis’ (our war of indelible memory),and the ‘swart gruwelregister’ (dark record of horror) remain too close to the surface for Dr Okulis and his fellow Arikaners to attempt to present and record it in a general history.[vi]

Despite its formal portrayal in the early 20th century, the genesis of the Volksmoeder as figurehead is firmly rooted in the nineteenth century. In the late 1880s the ‘Vrouwen Zending Bond’ (Women’s Missionary League) of the Dutch Reformed Church in the Cape Colony maintained that women, besides their housewifely duties, needed to play a constructive role outside the home in the church and the nation. Especially in the aftermath of the Anglo-Boer War, women nationalists considered it to be their duty to uplift their shattered fellow countrymen and women. In the Cape Province the ‘Afrikaanse Christelike Vroue Vereniging (ACVV)’ (Afrikaans Christian Women’s Society) chose a fitting nationalist slogan: ‘Church, Nation, Language’.[vii] In contrast to this high-minded ACVV slogan, in 1904 – pre-dating the Boervrou – the Transvaal South African Women’s Federation (SAVF) chose the quoted excerpt from Jan F Celliers’ poem. For them the uplifting of especially working class women and young girls represented the immediate challenge which would contribute concretely to the reconstruction of the nation idealised by the ACVV. Women needed constant reminders that they could triumph over adversity, could succeed at motherhood and would be able to resurrect the nation. Membership in the SAVF and service to the nation were considered to be the calling and the purpose of a Boer woman’s life and work. After twenty years of such service women were rewarded with so-called ‘Volksmoederknopies’ (Mother of the Nation buttons). These buttons were considered to be of such sentimental value that upon the death of the recipient, her button needed to be returned to the SAVF for safekeeping in a commemorative album.[viii]

During the first decades of the twentieth century these hard-working Volksmoeders moved away from their traditional areas of labour – social and welfare work amongst their fellow citizens – into more political playing fields. As a result of the 1914 Afrikaner Rebellion and the imprisonment of the Anglo-Boer War hero, General Christiaan de Wet and other rebel leaders, the ‘Klementiebeweging’ (Movement for Pardon) – later the ‘Nationale Vroue Helpmekaarvereniging’ (National Women’s Mutual Aid Society) – was founded. By means of local fundraising drives, large amounts of money were raised to pay the fines of these leaders so as to secure their release from prison. Petitions were circulated countrywide and were signed by 50 000 women. On 4 August 1915, about 3.000 women marched to the Union Buildings in Pretoria to present petitions to Governor-general Lord Buxton demanding the release ofGeneral De Wet and 118 other prisoners.[ix]

As a result of this protest action, the ‘Nasionale Vroue Party’ (NVP) (National Women’s Party) was founded in 1914 in the Transvaal and in 1922 in the Orange Free State. NVP chapters were organised in the Cape and Natal shortly thereafter. Members, middle-class NVP women, considered themselves to be the equals of, and not subservient to, their male counterparts in the National Party (NP). From the 1920s onwards the official mouthpiece of the VNP, ‘Die Burgeres’ (The Citizeness) urged its female readers to read and to extend their knowledge so as to be able to develop and express informed views on all political issues.[x] Likewise, in her column in Die Burger called ‘Vrouesake’ (Women’s Matters) the Afrikaans writer M.E. Rothmann known as ‘MER’ urged her readers:

… we women should acquire knowledge in order that we may be able to judge well and wisely, and that we may truly be able to serve our nation as citizenesses as well as (in the first instance!) Mothers.[xi]

In 1930 the NVP reached its zenith, but when white women were enfranchised in the same year, Volksmoeders were presented with a difficult choice. From all sides they were told that the true nationalist goal was not merely the attainment of political power, but the achievement of a higher ideal, that of the creation of a nation. The men of the NP called upon the NVP women to amalgamate with the NP in a spirit of sacrifice and cooperation in order to achieve the higher national goal in which women’s matters would be incorporated. Acquiescence to this request meant the demise of the NVP, whereupon Volksmoeders returned home to ‘save the nation’, individual household by household.[xii] The findings of the Carnegie Commission of Inquiry into the Poor White Problem of South Africa provided these women with a clear job description.[xiii] In essence more than 300.000 fellow Afrikaners, who lived in dire poverty, could not be allowed stray from the Afrikaner fold and needed to be saved.[xiv]

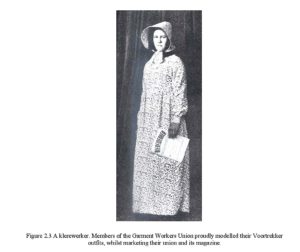

During the 1920s, the Great Depression of the 1930s, as well as during the hardships encountered during World War II, the Volksmoeder-figure sustained Afrikaans working-class women as well. During this time, as a result of the large-scale migration from the Transvaal and Free State countryside to the Witwatersrand, thousands of Afrikaans families led a hand-to-mouth existence in urban slums. Here young Afrikaans girls found work in the expanding clothing and tobacco industries as well as in local sweets factories. As their fathers and brothers could not readily find work, many became the breadwinners of the family. As members of the Garment Workers Union (GWU) under the stewardship of its well-known secretary, Solly Sachs, these young women became the storm troopers of a militant trade union. They loyally supported one another and their union, and fought for better working conditions. Their unionised actions caused not only their employers, but the fathers of the nations – the secret Afrikaner Broederbond, in particular – endless sleepless nights.[xv]

During the 1938 commemorative Great Trek celebrations, the Volksmoeder, a portrait in words and a two-dimensional figurine, became a three dimensional

figurehead. The Voortrekker outfit of Van Wouw’s Noitjie became the fashion statement of the time. Throughout the entire county, in villages and towns, women dressed in authentically recreated Voortrekker dresses and bonnets. They were accompanied on the Commemmorative Trek by men with newly-grown beards, waist coasts and leather trousers. Ox wagons such as the Johanna van der Merwe, the Magrieta Prinsloo and the Vrou en Moeder (Woman and Mother) representing and commemorating Great Trek heroines created a central place for women. Prospective young Volksmoeders entered into holy matrimony on many wagon kists, whilst others brought their children to be christened with names such as ‘Eufeesia’ or ‘Kakebeenia’. A decade later, in 1948, this rekindled fervour for a heroic heritage contributed substantially to the election victory of Afrikaner nationalism.

Figure 2.3 A klerewerker. Members of the Garment Workers Union proudly modelled their Voortrekker outfits, whilst marketing their union and its magazine.

In their own Kappiekommando (Bonnet Brigade) the young working Afrikaans women of the GWU shared in these emotion-laden celebrations. They likened their personal struggles for survival in the city with the hardships of life on trek. On the one hand, the factory women identified with the innocence and beauty of the colourful expression of Van Wouw’s ‘Noitjie’. On the other, they strongly identified with the courage and resolve of a generation of forceful, nearly forgotten women. They declared that as workers they would take the lead, and like Susanna Smit, they too would cross the Drakensberg on their bare feet.[xvi] However, unlike their middle-class sisters, their trade union with its goal of improving the lot of their fellow workers provided the context in which they worked. Anna Scheepers, a trade union leader declared in 1940:

‘… like the Voortrekker woman in this country, women workers contribute to the advancement of the trade union movement and the nation as a whole’.[xvii]

After World War II, as happened elsewhere in the world, women withdrew from the labour force. During the 1950s and 1960s fewer young women and daughters of these factory women entered the labour market. As a result of greater material prosperity, as well as the protective labour legislation of the apartheid years, fewer white married women needed to work.[xviii] At the same time, the state also began to play a greater role in addressing social and welfare issues. As a result, middle-class women who had previously found an outlet for their energies in voluntary welfare work, were able to enter the professional labour market. For example, for 17 years Johanna Terburgh worked as an unsalaried social worker for the Rand Armsorgraad (Rand Poor Relief Council) amongst impoverished young Afrikaans girls. During the 1950s she made a dramatic career change to become the director of an Afrikaans tourist bureau in Johannesburg.[xix]

During this globalising period, the Volksmoeder became an obsolete figurehead and forgotten figurine, clad in her long and now very old-fashioned Voortrekker dress gathering dust at the back of the cupboard. Yet, the Volksmoeder spirit survived as the characteristics of the Volksmoeder and of idealised womanhood were reshaped, repackaged and disseminated in a more sophisticated mould. During the early 1960s the Afrikaans translation of a book by an American sex expert, one H. Shryock, Die Ontluikende Vrou: ’n Boek vir Tienderjarige Meisies, (The Emerging Woman: A book for teenaged girls) was reprinted four times. In translation, the sex education section of the book read like a popular motor-mechanics manual, awash with clutches, nuts and bolts. In addition, the Volksmoeder’s idealised characteristics were presented more fashionably and with a distinctly international flavour. As before, the writer argued that it was appropriate for a young woman ‘to nurture a friendly and loveable manner’ and condemned the young woman who read too many novels and, as a result, did not devote herself to charitable works.[xx]

In the new, affluent suburbs, the Volksmoeder had to compete with the imported feminist ideas of a Steinem, Friedan or De Beauvoir. Hence, during the sixties and seventies, the Volksmoeder figurehead came to represent a narrow-minded and inflexible mindset. As a result of the onslaught of the modern, the Volksmoeder lost her traditional substance and power. In 1969 the Afrikaans poet M.M. Walters satirised the former figurehead:

Volksmoeders van V.V.V.-vergaderings

Onwrikbaar by die werk – kompeteer

By the pastorie(s)pens en bazaar – vol, voller, volste.[xxi]

(Volksmoeders at women’s meetings

Steadfast on the job – compete

At the parsonage, pantry, belly and bazaar – full, fuller fullest)

Yet the values which the Volksmoeder symbolised and championed managed to survive. Dr Jan van Elfen, a well-known Afrikaans writer of self-help manuals for a variety of audiences – mothers, daughters and sons – responded to the call to educate a new generation of Afrikaans women. Between 1977 and 1980 his life skills manual for young girls Wat meisies wil weet (What girls want to know) was reprinted five times.[xxii]

In a break with tradition, the blurb declares cheekily that ‘…every girl would like to know more about sex’. In line with these modern trends, Van Elfen discusses matters such as venereal disease, sexual feelings and lesbian relationships, and illustrates his sex education with anatomical diagrams. Yet, in a barely concealed manner, his warnings to his young readers echo the familiar old Volksmoeder message:

But you will not find happiness if you try too hard to break free from the rock from which you were carved … A person who liberates him/herself from what is his/her own, will be engulfed by life. It is most important that you should protect your identity (the person you are) … the religious and cultural values which you know so well; the view on life which you have acquired and life’s lessons which you have taken to heart and should make a permanent part of your personality as a teenager. It is these things that turn you into a good person, a person who will be welcomed into society.[xxiii]

With the outbreak of the clandestine war in Angola and the increasing violence experienced within the country after the 1976 Soweto Uprising, there was no mass movement of Afrikaans women who raised their voices for or against the war. Indeed, the patriarchs remained firmly in the saddle and women were advised that they should limit their involvement to supporting their husbands in the bedroom only:

… You should stand alongside him, even more so than during the times of the Voortrekkers when a woman had to stand next to her man…as a guard here in the bedroom, who with an intuitive ear listens to what is taking place in the deepest recesses of the nation …[xxiv]

Afrikaans women had to strike a balance between the ‘total onslaught’ on Afrikanerdom and the lives of their children. It is almost as if Afrikaans women had forgotten that they were indeed flesh-and-blood mothers of a nation of young men confronting other mothers’ sons on the battlefield. At grassroots level they merely baked rusks, biscuits and sticky-sweet ‘koeksisters’. Every Saturday afternoon on the programme ‘Forces Favourites’, they broadcast syrupy messages to their sons and the troops on the border. How did mothers react when their sons returned from the border dead, wounded or ‘bossies’ – Afrikaans shorthand for post-traumatic stress syndrome?

Today the concept of a narrowly defined Volksmoeder as a site of memory elicits contradictory responses from a random sample of Afrikaans women. Anchen Dreyer, a senior member of the national parliament, is of the opinion that the Volksmoeder should not be seen only as a symbol of narrow-mindedness and regression. Rather, the Volksmoeder also has enviable characteristics: independent views, entrepreneurship, survival skills, and a history of self-help and social uplift.[xxv] Marinda Louw, a 30-year old publisher, maintains that women with strong personalities – real mothers of the nation – can be found everywhere, across racial and cultural divides. She feels that women have a greater capacity for human involvement, for gauging people’s needs and how to fulfil these needs.[xxvi] Dalena van Jaarsveld, a post-graduate student in anthropology and now a journalist who grew up in the new South Africa, agrees:

‘… There is no longer a cultural mother of South Africa, only real mothers who plait hair, who are loving and hospitable and who nurture many children’.[xxvii]

NOTES

i. The figure forms part of Van Wouw’s oeuvre of small statues, which includes depictions of Paul Kruger, black miners and San/Bushmen hunters. M.L. du Toit, Suid-Afrikaanse Kunstenaars, Deel I: Anton van Wouw. Cape Town: Nasionale Pers 1933, 29. In 2009 the original cast of the Volksmoeder was auctioned for almost R1 million. All translations from Afrikaans into English by the author.

ii. It was published by Mabel Malherbe, a formidable woman who became the first female mayor of Preoria and the second female member of the parliament of the Union of South Africa; a veritable Volksmoeder forever engaged in the struggle.

iii. J. Snyman, ‘Die politiek van herinnering: spore van trauma’, in Literator 20(3) November 1999, 15-16.

iv. Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge, Afrikanerbakens, Johannesburg: FAK 1989, 102.

v. Dr Okulis (Postma W.), Die Boervrou: Moeder van haar Volk. Bloemfontein: Nasionale Pers, 1922, ii.

vi. W. Postma, Die Boervrou: Moeder van haar Volk. Bloemfontein: Nasionale Pers, 1922, 141-142. The fact that only 15 pages of a book with 234 pages dealt with the Anglo-Boer War probably indicates just how difficult Postma found it to write about the war.

vii. M. du Toit, ‘The Domesticity of Afrikaner nationalism: volksmoeders and the ACVV, 1904-1929’, in: Journal of Southern African Studies 29(1) March 2003, 163-167.

viii. E. Brink, ‘Man-made Women: Gender, class and the ideology of the volksmoeder’, in C.Walker, (ed.) Women and Gender in Southern Africa to 1945. Cape Town: David Philip 1990, 286-288.

ix. A. Ehlers., ‘Die Helpmekaarbeweging in Suid Afrika: die Storm- en Drangjare, 1915-1920’, in Argiefjaarboek vir Suid Afrikaanse Geskiedenis, Jaargang 54, Vol I, Pretoria: Government Printer, 1991.

x. L. Vincent, ‘Power behind the Scenes: The Afrikaner Nationalist Women’s Parties, 1915-1931’, South African Historical Journal 40, (May 1999), 56-59.

xi. Die Burger, 29 Desember 1925: M. du Toit, ‘The Domesticity of Afrikaner Nationalism: Volksmoeders and the ACVV, 1904-1929’, in: Journal of Southern African Studies. 29(1) March 2003, 7-69.

xii. Ibid.

xiii. Carnegie Commission, The Poor White Problem in South Africa, Vol.I-V. Stellenbosch: Pro-Ecclesia Publishers, 1932. MER’s report, The Mother and Daughter of the Poor White Family was incorporated separately in Vol. 5.

xiv. D. O’Meara, Volkskapitalisme: Class, Capital and Ideology in the development of Afrikaner Nationalism. Johannesburg: Ravan Press 1983, 26.

xv. E. Brink, ‘The Afrikaner women of the Garment Workers Union, 1918-1939’. Unpublished MA, University of the Witwatersrand, 1986.

xvi. E. Brink, ‘Man-made Women: Gender, class and the ideology of the volksmoeder’, in C. Walker, (ed.) Women and Gender in Southern Africa to 1945. Cape Town: David Philip, 1990.

xvii. E. Brink, ‘Purposeful Plays, Prose and Poems: The writing of the Garment Workers, 1929-1945’ in C. Clayton, Women and Writing in South Africa: A Critical Anthology. Johannesburg: Heineman, 1989, 112.

xviii. As in the past, women who were engaged in wage labour, were studied in depth; on this occasion by one Dr. Mrs D.M. Wessels, Vroue en Moeders wat Werk: Die Invloed van hul Beroepsarbeid op die Huisgesin en die Volk, Kaapstad: NG Kerk-Uitgewers, 1960.

xix. E.L.P. Stals, Afrikaners in die Goudstad, Vol. II. Pretoria: HAUM 1986, 38-40. Also the University of Johannesburg’s Archive on the Afrikaners on the Witwatersrand, A54, Johanna Terburgh Collection. Terburgh was actively involved in the Handhawersbond, a society working for the promotion of the Afrikaans language.

xx. H. Shryock, Die ontluikende Vrou; ʼn Boek vir tienderjarige meisies. Cape Town: Sentinel 1961, 108.

xxi. M.M. Walters, Apochrypha. Cape Town: Nasionale Boekhandel 1969.

xxii. J. van Elfen, Wat Elke Meisie wil Weet. Cape Town: Tafelberg, 1977. In addition to his illustrated guidance manuals for teenagers, he wrote extensively on the care of babies, toddlers and children, along with a medical guide for women and a book on love and sex in marriage.

xxiii. J. van Elfen, Wat Elke Meisie wil Weet. Cape Town: Tafelberg, 1977 6.

xxiv. L. Maritz, ‘Vroue, ons stille vegters’, in: Die Burger, 3 February 2007.

xxv. Interview with Ms Anchen Dreyer, 25 July 2007, Johannesburg.

xxvi. Interview with Ms Marinda Louw, 21 August 2007, Johannesburg.

xxvii. Interview with Ms Dalena van Jaarsveld, 11 August 2007, Mtunzini.

References

Unpublished

Interview with Anchen Dreyer, 25 July 2007, Johannesburg.

Interview with Dalena van Jaarsveld, 11 August 2007.

Interview with Marinda Louw, 21 August 2007, Johannesburg.

University of Johannesburg, Archive of the Afrikaners at the Witwatersrand, A54 Johanna Terburgh collection.

Published

Brink, E. ‘The Afrikaner women of the Garment Workers Union, 1918-1939’. Unpublished MA-thesis, University of Witwatersrand 1986.

Brink, E. ‘Purposeful plays, prose and poems: The writing of the garment workers, 1929-1945’, in: C. Clayton. Women and writing in South Africa: A critical anthology. Johannesburg: Heineman 1989.

Brink, E. ‘Man-made women: Gender, class and the ideology of the volksmoeder’, in: C. Walker (ed.). Women and gender in Southern Africa to 1945. Cape Town: David Philip 1990, 286-288.

Carnegie-kommissie. Die armblanke-vraagstuk in Suid-Afrika, Vol. I-V. Stellenbosch: Pro-Ecclesia Drukkery 1932.

Du Toit, M.L. Suid-Afrikaanse kunstenaars, Deel I: Anton van Wouw. Cape Town: Nasionale Pers 1933.

Ehlers, A. ‘Die Helpmekaarbeweging in Suid-Afrika: Die storm- en drangjare, 1915-1920’, in: Argiefjaarboek vir Suid-Afrikaanse Geskiedenis, Jaargang 54, Vol. I. Pretoria: Government Printer 1991.

Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereneginge. Afrikanerbakens. Johannesburg: FAK 1989.

Maritz, L. ‘Vroue, ons stille vegters’, in: Die Burger, 3 February 2007.

O’Meara, D. Volkskapitalisme: Class, capital and ideology in the development of Afrikaner nationalism. Johannesburg: Ravan Press 1983.

Postma, W. Die boervrou: Moeder van haar volk. Bloemfontein: Nasionale Pers 1922.

Shryock, H. Die ontluikende vrou: ‘n Boek vir tienderjarige meisies. Cape Town: Sentinel Uitgewers 1961.

Snyman, J. ‘Die politiek van herinnering: Spore van trauma’, in: Literator 20(3), Nov. 1999.

Stals, E.J.P. Afrikaners in die Goudstad, Vol. II. Pretoria: HAUM 1986.

Van Elfen, J. Wat elke meisie wil weet. Cape Town: Tafelberg 1977.

Vincent, L. ‘Power behind the scenes: The Afrikaner nationalist women’s parties, 1915-1931’, in: South African Historical Journal 40, May 1999, 56-59.

Walters, M.M. Apochrypha. Cape Town: Nasionale Boekhandel 1969.

Wessels, D.M. Vroue en moeders wat werk: Die invloed van hul beroepsarbeid op die huisgesin en die volk. Cape Town: NG Kerk Uitgewers 1960.