Reshaping Remembrance ~ The Voortrekker In Search Of New Horizons

No Comments yet To forget and – I will venture to say – to get one’s history wrong, are essential forces in the making of a nation.[i]

To forget and – I will venture to say – to get one’s history wrong, are essential forces in the making of a nation.[i]

We are marshalled into two lines – boys to one side, girls to the other. I am wearing a long volkspelerok, a lilac folk dress the exact shade of jacaranda blooms, dutifully sewn by my gran Mémé. I feel the traditional white lace kerchief scratching my neck, my feet resisting the pinch of my brand-new black school shoes, neatly buckled over a pair of white socks. Earlier this morning I took down the frock from where it was hanging, covered in plastic and reeking of mothballs, next to my virginal white Holy Communion dress. Sister Boniface bends over the record player. Her Dominican nun’s habit is daringly fashionable, the hem barely covering her knees. As the first chords of Afrikaners is plesierig fill the air, we take up our positions. Sister Boniface puts her hands around sister Modesta’s waist, and they twirl away.

In the singing class, we are taught ditties from the FAK songbook, a treasure trove of light Afrikaans song: My noointjie-lief in die moerbeiboom; Wanneer kom ons troudag Gertjie; Sarie Marais… Sister Boniface sings in perfect Afrikaans, tinged with a melodious Irish accent – tranforming the dust and plains of our language into moss and peat.

At the end of standard five I leave the Afrikaans convent school (the only Afrikaans convent in the world!) and move on to a big Afrikaans girls’ school. The principal conducts the standard six girls to a bronze cast of Anton van Wouw’s Die Noitjie van die Onderveld (‘Simple country girl’).

The Voortrekker girl stands about one foot (30cm) tall on a stone podium; feet together, hands crossed. Her head is slightly bowed; the small, bronze face barely visible and shaded by her kappie (bonnet). There is something despondent about her stance. ‘This, girls,’ the principal informs us, ‘is an example of the demeanour of a respectable young Afrikaans lady – proper, humble, chaste.’

However, at this school, the Voortrekker girls wear neither long dresses, nor bonnets. They are robust and rowdy, with muscular hockey calves and ruddy cheeks. After school they march and salute in their brown militaristic uniforms, singing cheery songs about camp fires and magtige dreunings (mighty rumblings)[ii]. I soon realise that the nuns, despite their brave efforts to turn me into a culturally authentic Voortrekker girl, have failed dismally. Here my knowledge of volkspele steps and FAK songs is meaningless.

I struggle to get a grip on the more subtle, underlying cultural codes. Due to my European Catholic background, I remain an outsider, and I am confronted with an impenetrable Afrikaans ‘laager’; for the first time I hear about the Roomse gevaar (the so-called Roman Catholic ‘menace’), the Swart Gevaar (Black ‘danger’), the Rooi Gevaar (Red ‘onslaught’). I realise that I am not an Afrikaner, even though my Flemish parents speak Afrikaans to us at home. I discover that I could never be one of them, no matter how hard I tried. I come to understand that my mother tongue is not the language of my mother, which makes all the difference.

Now, almost thirty years later, I shake my head in disbelief as I peruse a Sanlam advertisement in Insig.

‘Meet the New Voortrekkers’, the advertisement proclaims, introducing readers to a group of young, confident, multiracial and androgynous artists. Long forgotten is the chaste and humble country girl. Forgotten too the militaristic and exclusive youth movement standing for racial and cultural purity. The only requirement is that Die Taal (‘The Language’) be spoken with pride. Clearly the Voortrekker, as a locus of remembrance, is also a place of deliberate forgetting.

Though national identity has often been regarded as God-given, and therefore imagined as something natural and primordial, it is not generally acknowledged as a relatively modern notion – namely that of a fictitious community construed in a premeditated and deliberate fashion, usually in times of crisis when the survival of a particular society was at stake.[iii] As such, the Afrikaners presently occupy an interesting position, seeing that they used to be a rather undefined and divided ethnic group, once self-fashioned as a nation, and now demoted to only one of many African tribes whose tribal adherence presents a threat to the integrity of the unstable postcolony. From nation to tribe – moreover, a tribe with pariah status! A change of this order (in a community for whom self-determination has always served as a historical metanarrative) must of necessity inflict traumatic wounds to the collective self-concept. This liminality (between ethnicity and nationality, tradition and global modernity, dominance and disadvantage, colonialism and postcolonialism) is precisely what interests me with regard to the image of the Voortrekker. It is an image that has undergone significant changes: originating from historic events in the 19th century, becoming an icon of the Volk (Nation) in the 1930s, and finally evolving into a symbol of a more inclusive, cynical, militant and/or critical understanding of the Afrikaner’s role in the New South Africa.

2.

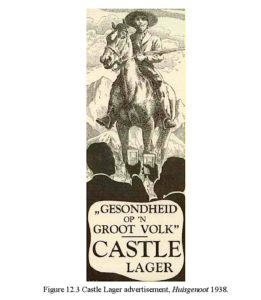

The Great Trek, along with the figure of the Voortrekker, was generally accepted as the hallmark of Afrikaner origin and identity. The centrality of this historic event in the Afrikaner’s national consciousness was, however, only established during the fervent and carefully orchestrated nation-building campaign of the 1930s and 1940s. At the time the Afrikaners’ survival as an ethnic group was under threat due to (inter alia) the depression, the dividing character of Unionist politics, and a competitive black upward mobility. The ideologically-driven and renewed interest in the Great Trek during the 1930s secured the figure of the Voortrekker as an icon of the Afrikaner nation and a beacon of Afrikaner nationalism. Nations are often portrayed as a solitary figure. One only has to think of the allegorical ‘Statue of Liberty’ depicting the myth of a free and fair America. The continuous representation of the Voortrekker image in Afrikaans newspapers and magazines (a striking example of the irreplaceable role of press capitalism in the process of creating a nation) has deeply etched the bearded patriarch on horseback and his modest but stalwart bonneted wife into the Afrikaner imagination.

Clearly this national ideal struck all the right chords to mobilise and unite the depression-ridden Afrikaner. During the commemorative ox-wagon trek of 1938 the men grew beards, while the women wore bonnets and long dresses. Hundreds of couples in traditional Voortrekker attire were married alongside the ox-wagons, and many children of the commemorative trek were aptly named Ossewania and Eeufesia – derivatives of the Afrikaans word for ox-wagon (‘ossewa’) and centenary festival (‘eeufees’) respectively.

The obsessional continuation of a stereotype (such as that of the heroic Voortrekker in the Afrikaans magazine Die Huisgenoot of the 1930s) pays tribute to the unmistakable presence of self-awareness and the accompanying psychological unease and anxiety.[iv]

Over-articulation is a means to suppress the insight that the stereotype is an imaginary construct, thereby quelling any fears that the heroic Voortrekker might be a mere myth, while affording an image to be exploited for political purposes. In the global imagination, however, it is not the narcissist, allegorical self-portraits of nations and ethnic groups that dominate, but the less attractive stereotypes: Bruce and his kangaroo-skin hat, sporting corks to ward off the flies; Hans with his lederhosen and big belly. Following the 1948 election victory, the ethnically exclusive image of the Voortrekker was turned into a national emblem.[v] The Great Trek was foregrounded as every South African’s legacy. The Grand Narrative of the Voortrekker was told and retold in all South African history school books, and symbols associated with the Great Trek (the torch, the ox-wagon, the iconic figure of the Voortrekker) were forced down all South Africans’ throats by every available medium and means – from postage stamps to the national anthem. This cultural violation caused irreparable damage to the image of the Afrikaner, giving rise to a less flattering stereotype – that of the Afrikaner as a thick-necked, khaki-clad, brutal racist.

More than any other structure, the Voortrekker monument embodies the narcissism, paranoia and chauvinism of the Afrikaner during the apartheid years. This monolithic monument, surrounded by its circular and uninterrupted laager of ox-wagons carved in stone, exemplifies a central aspect of identity formation, namely exclusivity. The establishment of an inclusive ‘we’ always goes hand in hand with a negative description of the rejected Other. In fact, the definition of the Self (embodied in the civilised, Godfearing and valorous Voortrekker) is positively dependent on a clearly defined(primitive, bloodthirsty and cowardly) Other. Especially in the Hall of Heroes, where a procession of large marble relief panels tells the story of the Trekkers’ struggle to bring the light of civilisation to Darkest Africa, the subtext of self-righteousness and selfglorification is quite clear. To the scores of white Afrikaans children visiting the monument on school excursions, the image of the defenceless Voortrekker children and women overpowered by hordes of cruel savages must have made a lasting impression. Similarly the patriarchal nature of Afrikaner culture was reinforced by the brave heroes coming to their rescue.

The inauguration of the monument on 16 December 1949, shortly after the Nationalist Party had come into power in 1948, not only proclaimed the political triumph of Afrikaner nationalism, but also implied that this victory was divinely sanctioned. Just as the victory of the hugely outnumbered Voortrekkers against the Zulus at Blood River proved to Afrikaners that they were God’s chosen people, the unlikely victory of the Nationalist Party in 1948 was similarly interpreted as a divine intervention. The fact that nationalist monuments are often drenched in religious symbols is no coincidence.[vi] In the same way that the secular nation state had replaced the theocracy of the middle ages, the magical symbolism of religion was later applied to underpin the power of the state. In the process the identity of Afrikaner nationalism and the Protestant religion became inextricably linked.

But no nation’s self-fashioning remains intact. As the crisis that faced the Afrikaners in the 1930s and early 1940s faded, and they increasingly profited from the ‘affirmative’ practices of the Nationalist government, the general profile of the Afrikaner changed drastically.[vii] The changing status of the average Afrikaner, together with the inevitable claims made by the country’s displaced black population, would of necessity impact on the Afrikaner’s self-image. Ideological and class differences that had always existed in Afrikaner ranks, though temporarily erased by a mutual desire for political and cultural recognition, emerged more strongly than ever, and right-wing Afrikaners increasingly tended to appropriate the cultural symbols of a united nation.[viii] A growing number of cosmopolitan Afrikaners would in due course become either apathetic towards, or embarrassed by their Nationalist heritage. A younger generation was soon to discover that the ‘feats’ of their forefathers had actually been deplorable, and that it was becoming rather ‘common’ to make a display of one’s Afrikaner roots.

It is generally accepted that the establishment of powerful icons sets the scene for iconoclasm. Most of today’s young Afrikaners, having escaped the programmatic cultural indoctrination of their parents, are no longer interpellated by the heroic Voortrekker narrative. For the new Afrikaner generation, an obvious way to deal with the chauvinistic outrages and the subsequent pariah status of their cultural heritage, is to reject and ridicule the historical cultural symbols.[ix] It therefore comes as no surprise that many young Afrikaners regard the identification with the collective symbols of a bygone era of Afrikaner glory as naive. T-shirts sold at the Klein Karoo Kunstefees (‘Little Karoo Arts Festival’) equated the ox-wagon (colonial motif of Western civilisation in the dark heart of Africa) with ‘trailer trash’. At the opening of the Spier Contemporary art exhibition in 2007, a young Afrikaans arts collective parodied the Voortrekker and other outdated Afrikaner symbols, and no-one batted an eyelid. Caricatures of the naive, obtuse Boer have become commonplace in the media and entertainment industry.

The opposite also applies, however. One has to keep in mind that the generation of young Afrikaners now sitting at their school desks, has to a large extent been spared the programmatic excesses of apartheid propaganda. To them the stories of brave Voortrekkers and the heroes of the Anglo-Boer war seem brand-new. These inspiring narratives pose a welcome alternative to the negative role assigned to Afrikaners by post-apartheid history. The unprecedented and unexpected success of Bok van Blerk’s song about De la Rey, a once famous Boer general, points towards a fertile breedingground for rekindling the Afrikaner nationalist sentiment amongst young Afrikaners. This apparent need for a positive identification with one’s Afrikaans heritage should in fact come as no surprise.

In terms of a Freudian interpretation, the Afrikaner’s traumatic political disempowerment and the destruction of his self-concept have been transferred to a process of mourning and, eventually, healing. The glorious story of the Afrikaner, cast in the mould of the Great Trek and endlessly reified in the school history taught during the apartheid years, has become a lost object of mourning. The heroic figure of the armed and mounted Boer finds its final, convulsive revival in the figure of De la Rey. The spate of articles on Afrikaner identity, the bitter polemics on the Boer War and other key events in Afrikaner history, are symptomatic of catharsis. By way of discussion and analysis, the mythical object of mourning is gradually discarded. The teleological, symphonic Grand Narrative of the Great Trek finally makes way for an insurgence of the real. In this way a more balanced understanding of history (history as a web of numerous contingent, disrupted, many-sided, contradictory and polysemic narratives) is gradually emerging.

But is a Freudian interpretation of this nature viable? I doubt it. Freud underestimates the perverse readiness of the collective (any collective!) to forget. The bitter indignation, discontent and obscene self-pity (about affirmative action; about the new dispensation’s ‘suppression’ of Afrikaans) that often slur letters to the Editor in the Afrikaans press, are signs of a surprisingly short memory. But what does this need to forget signify? Paul Ricoeur points out that it is not coincidental that the words ‘amnesia’ and ‘amnesty’ have the same etymological origin. The desire for oblivion signifies a need for indemnification rather than forgiveness – the need to forget that forgiveness must be asked.[x]

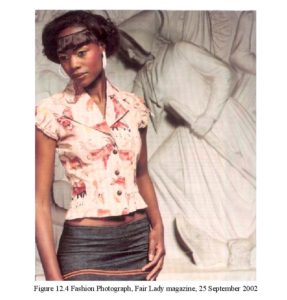

Therefore it is hardly surprising that the Voortrekker monument, representing an imaginary sense of unity and adherence to the exclusivity of the Afrikaner, still serves as the primary symbol of an Afrikaner ‘essence’. In a telling photograph from the transitional political phase of 1990 to1994, Tokyo Sexwale takes up a triumphant stance inside the laager. In a more recent fashion magazine, an elegant black model poses in front of one of the monument’s marble relief tiles, right inside the sanctuary of the monument itself.

But here the familiar colonial dualism is markedly reversed: modernity, youth and prosperity are depicted as features pertaining to Africa, and represented by the model wearing a colourful top decorated with rock-art motives, while the Voortrekker woman (preserved for posterity in her pale bonnet and long dress), is reminiscent of the obdurate past.

3.

One question now remains: are there any possibilities whatsoever of recapturing the Voortrekker image, apart from a nostalgic-atavistic right-wing revival (as the De la Rey phenomenon is often interpreted) or the flippant oblivion portrayed in the Sanlam advertisement? Is this advertisement’s banal therapeutic multiculturalism (if the old white Voortrekker was the disease, the new multiracial Voortrekker is the cure) the only way for Afrikaners to claim their heritage without compromising their loyalty to the New South Africa? Not necessarily so. Self-reflection and humour offer alternative, more nuanced opportunities for fundamental reflection on Afrikaans places of remembrance.

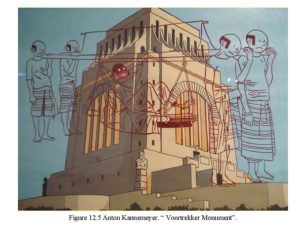

Anton Kannemeyer’s ‘Voortrekker Monument’ examines the fear of retaliation that possibly underlies the numerous debates about the future and nature of the Afrikaner in the New South Africa.

He overwrites the authoritarian aspect of the Voortrekker monument with a spectre of four identical middle-aged white men (caricatures of Kannemeyer himself?) who, in a parodic inversion of the colonial cliché, are carrying a black man in a hammock. The overtly stereotyped features of the man in the hammock signifies the deeply-rooted nature of white preconceptions about Africans – the very preconceptions manifesting in the Voortrekker monument. The power of the intimidating monument, founded on the radical exclusion and degradation of the Black Other, is undermined by exactly those fears, inferiority complexes and feelings of guilt that were to be allayed by the erection of the monument. Here disillusion bears self-knowledge, a fruit that is not to be despised.

In Minette Vari’s video installation, ‘Chimera’ (2001), the Voortrekker monument is also exploited as a forum for radical self-examination. Vari uses the marble reliefs in the Hall of Heroes as a background against which she projects the white man’s profound unease with Africa. Using an insert of her own naked body, Vari disrupts the reliefs’ self-glorifying version of history.

Her body is constantly transformed from a shamanlike shepherd to a flying woman with the head of a beast. This perpetually moving and changing spectre destabilises the hierarchic stasis of the panels and disrupts the symphonic flow of the narrative with an ominous dissonance. Freud’s concept of unheimlichkeit – the sudden, disconcerting strangeness of the familiar – is brought into play.[xi] The disturbing figure of the animal-like chimera alludes to a post-humanistic vision of identity that undermines the essentialist stereotypes in the Hall of Heroes. Here the white body literally becomes alienated,

whereby the artist not only articulates her own alienation as a disillusioned South African, but also the inherent strangeness and flux of identity as such. In this way the Afrikaner’s story of self-justification is transformed into a narrative of displacement. As any account is always selective, thus serving to mask ideological agendas, bodily experience is here applied to resist the narrative, or even to contradict it. Vari does not repeat or recount the story of the Voortrekkers in a different way, but the story itself is infiltrated and disrupted by the artist’s personal experience of radical strangeness and the traumatic discomfort of being an Afrikaner and white person.

By playing visual games with the iconic status of the Voortrekker monument, both Kannemeyer and Vari demonstrate that instead of regarding places of remembrance as places of reappropriation (of a monolithic Self), they can be reinvented as loci of reflection for promoting self-knowledge. This may be one way of confronting the Afrikaner individual with his personal alienation, displacement and hybridity, thereby possibly enabling him to revel in a newly discovered, celebratory freedom.

NOTES

i. Ernest Renan in E. Heidt. 1987. Mass media, cultural tradition, and national identity. Fort Lauderdale: Verlag Breitenback, 131.

ii. In the rousing, patriotic Afrikaner nationalist song, Die lied van jong Suid-Afrika, the ‘mighty rumblings’ referred to here are the sound of a young nation rising.

iii. Andries Treurnicht articulates the idea of ‘nations’ as an integral part of a God-given command: ‘If you believe … that God has a mission for those exceptional individuals called nations, if you believe that you are meant to survive as an identifiable nation to fulfil your specific calling, can it be right to neglect your nation’s characteristic feature, its feeling of unity, its nationalism, its identity?’. A.J. Botha. Die evolusie van ’n volksteologie. D.Th. dissertation, University of the Western Cape 1986, 131. According to Benedict Anderson, however, the nation is an imaginary society, purposefully created for the political survival of a particular society or ethnic group. B. Anderson. Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso Books 1983.

iv. H. Bhabha. ‘The other question: Stereotype, discrimination and the discourse of colonialism’, in: H. Bhabha. The location of culture. New York: Routledge 1994.

v. It is significant that the building costs of the monument (£360 000) were largely borne by the government. Another telling factor is that the monument was privatised in the 1990s, when it became apparent that the dispensation was to meet with major changes. Compare the text by A. Grundlingh: ‘A cultural conundrum? Old monuments and new regimes: The Voortrekker Monument as symbol of Afrikaner power in a postapartheid South Africa’, in: Radical History Review 81 (2001).

vi. B. Anderson. Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso Books 1983.

vii. According to Grundlingh, the Nationalist Party’s regime resulted in the urbanisation of 84% Afrikaners towards 1974. From 1948 to 1975 the number of Afrikaners occupying white-collar positions escalated from 28% to 65%, while Afrikaners in the agricultural sector and industry experienced a sudden heave. As a consequence the rise of the Afrikaans middle classes was established during the economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s. A. Grundlingh. ‘A cultural conundrum? Old monuments and new regimes: The Voortrekker Monument as symbol of Afrikaner power in a postapartheid South Africa’, in: Radical History Review 81 (2001), 99.

viii. One only has to think of the 150th commemoration of the Great Trek in 1988, where efforts to revive the former political victory failed dismally when the centenary festival was hijacked by rightist movements such as the AWB (an Afrikaner resistance movement).

ix. The German philosopher, Jurgen Habermas, identified this process, as demonstrated by German youths, as a reaction against the Nazi outrages of the Second World War. J. Habermas. ‘A kind of settlement of damages: On apologetic tendencies in German history’, in New German Critique, Spring/Summer 44 (1988), 34-44

x. ‘It is not by chance that there is a kinship, a semantic kinship … between ‘amnesty’ and ‘amnesia’. The institutions of amnesty are not the institutions of forgiveness. They constitute a forgiveness that is public, commanded, and that has therefore nothing to do with … a personal act of compassion. In my opinion, amnesty does wrong at once to truth, thereby repressed and as if forbidden, and to justice, at it is due to the victims.’ S. Antohili, ‘Talking history: Interview with Ricoeur’, www.janushead.org/8-1/Ricoeur.pdf [Retrieved 23 September 2007].

xi. L. van der Watt. ‘Witnessing trauma in post-apartheid South Africa: The question of generational responsibility’, in: African Arts 38 (3) (2005).

References

Anderson, B. Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso Books 1983.

Antohili, S. ‘Talking history: Interview with Ricoeur’, www.janushead.org/8-1/Ricoeur.pdf.[Retrieved: 23 September 2007].

Bhabha, H.K. ‘The other question: Stereotype, discrimination and the discourse of colonialism’, in: The location of culture. New York: Routledge 1994.

Botha, A.J. Die evolusie van ‘n volksteologie. Unpublished D.Th. dissertation, University of the Western Cape 1986.

Grundlingh, A. ‘A cultural conundrum? Old monuments and new regimes: The Voortrekker Monument as symbol of Afrikaner power in a post-apartheid South Africa’, in: Radical History Review 81 (2001).

Habermas, J. ‘A kind of settlement of damages: On apologetic tendencies in German history’, in: New German Critique, 44 (Spring/Summer ), 34-44.

Heidt, E. Mass media, cultural tradition and national identity. Fort Lauderdale: Verlag Breitenback 1987.

Van der Watt, L. ‘Witnessing trauma in post-apartheid South Africa: The question of generational responsibility’, in: African Arts 38 (3) (2005).

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply