Spinoza ~ The Philosopher Of Counter-Radicalization

Spinoza Lecture 2016 – Amsterdam, November 27

Part 1 ~ Personal meaning

It’s an honour to address the Spinozakring in Amsterdam on Spinozadag. As a young man, I was living in Belfast during the darkest years of the terrorist Troubles, when I set out for Trinity College, in Dublin to begin 5 years of post-graduate research on the subject: “Spinoza’s Ethics and the Meaning of Life.”

What followed was an unequal struggle – Spinoza was even more challenging than I thought – and I didn’t find the meaning of life. In the process, I struggled, mentally. No one I met seemed the slightest bit interested in Spinoza and the more I read and understood The Ethics, the more isolated, anxious and remote from everyday life I became – as if I was going in one direction and everyone else was headed in another.

And during those difficult years, I learned new ways of thinking and Being – perspectives and insights on life and the human condition. Things that have stayed with me to this day; that made me who I am; and that will – I hope – play an important part in my future. After much difficulty, I learned to see and understand the world the way Spinoza saw it.

Spinoza became my anchor – my reference – for exploring life — a beacon of intellectual strength and independence. ‘The Philosopher of Amsterdam” – became my cultural hero in Belfast – not only for his philosophy, but for his character. And just as he was an outsider in his community, so was I.

I learned that the concept of Unity – of living with an attitude towards One-ness, cohesion, and cooperation — was central to Spinoza’s thinking and that his greatest work, The Ethics, described a path to a radical form of mental health through three mutually reinforcing forms of unity, designed to cure three kinds of division.

The first step is to heal and unite the divided self, to overcome conflicted and self-harming emotions, using his psychology; the second, is to unite us with others in strong bonds of friendship, guided by his radical humanism; the third, a cure for ontological alienation in moments of insight when our drop-consciousness joins in an oceanic experience with the eternal.

These three perspectives on human existence – the psychological, the pragmatic and the metaphysical – define why Spinoza’s thinking is so powerful.

Part 2 ~ The two truths

And this brings us to the tension at the centre of his Ethics – and indeed, the terrible contradiction at the heart of the human condition – one that generates so much religious superstition and metaphysical speculation. I’ll try and put this as clearly as possible.

The first self-evident truth of the human condition is the subjective truth of Being, how we feel as we look outwards onto the world. We’ve already beaten astronomical odds to arrive as self-conscious beings and sense the significance of our moment. The truth of our individual identity – that we are separate and distinct from everything else – places us at the centre of our universe. We instinctively prioritize our needs and drives, those we love and care for, and the projects we value. Above all, we want our chance at life to continue.

The second self-evident truth – and it is just as mysterious — is that none of this matters. From the perspective of timeless eternity, whether we live or die, whether our projects succeed or fail, what we want for ourselves and others, means nothing. Everything we value – including our lives – will be taken from us, often brutally, no matter how hard we fight, how much we care, or how good or valuable we are to Mankind. If you want to believe our lives and hopes matter in some objective way, chose a religion, but don’t read Spinoza to find the answer.

These two truths represent life and death, or more accurately, time and eternity. They’re at war with each other and define the drama of the human condition. Their conflict inspires great art, writing, theatre and music — acts of courage, love and self-sacrifice. But it also drives the dark side – depression, meaninglessness, war, suicide …. and violent extremism. The conflict is resolved in death, in that the second truth always wins – and we, as individuals – must surrender. But, it’s our defiance, our stubborn striving to hold our identity in the face of inevitable loss that makes the human condition feel like a restless, if not urgent, roller-coaster ride.

Like many great thinkers, Spinoza tries to reconcile these two truths… and he does it beautifully. He teaches us how both perspectives, both truths can be held and experienced simultaneously. He shows us a way to bring them together as a lived experience – purely for the love, strength and peace of mind — it brings us. This is his magic.

His Ethics has gifted us a strange, extraordinary, philosophy; – of this world, and yet not of this world – that makes it one of the truly great philosophical masterpieces.

Part 3 ~ What do I do for Amsterdam?

Today, I’m a practitioner in counter-radicalization — not an academic. It was more than 30 years ago – in Jesus College, Oxford – that I last gave a lecture on “Spinoza’s Humanism” – so forgive me if I am a bit rusty. I’m proud of my role as an advisor to the City of Amsterdam – in particular, for the opportunity to advise a Mayor who is not only a world-class politician – but a considerable fan of Spinoza.

Today, I’m also speaking for myself, since I also advise a number of governments and organizations around the world. Most of my work can’t be made public. My approach is rooted in witnessing first-hand the community radicalization and violence in Northern Ireland, my training as a psychoanalyst – a decision inspired by reading Spinoza – and the intensity of my work in warzones. But, what part does Spinoza play? How could ideas which were around 350 years ago, possibly impact on today’s very modern and complex issues?

Well, today – since it’s Spinozadag – I’m going to present Spinoza as “The Philosopher of Counter-Radicalization.” So far as I know, this is a world first. There are three ways his philosophy can help us.

The first is to use his theory of human emotions in The Ethics to re-think our approach to preventing radicalization

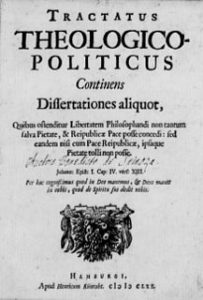

The second is to follow his radical intellectual lead in the Theological-Political Tractatus (TPT) to re-frame the situation the West finds itself in

The third is to use his political philosophy – with its emphasis on social cohesion and the management of hope over fear — to prevent polarization and radicalization.

My 4 axioms

Before I make the case, there are four simple axioms I use everyday that are inspired by Spinoza’s thinking.

a) First, understand causes rather than react

b) Secondly, “Do No Harm” to our Here, I follow Spinoza’s personal motto “Caute” – caution. The history of countering terrorist recruitment is littered with own-goals.

c) Third: if we are to understand decisions and direction, we must understand emotions.

d) My final axiom is, “Be pragmatic, not ideological – take the path of least resistance.”

Three kinds of wrong framing

The first question of counter-radicalisation is…. “What’s the most effective way to prevent terrorist recruitment without harming ourselves?”

Well, Spinoza inspires us to take a bold new approach — as he did himself. At the beginning of the Theological-Political Tractatus he says, “All men are by nature liable to superstition” and, since we must re-think where we are, we must first examine our own false narratives and superstitions.

Not a “Clash of Civilizations”

The most damaging superstition is the West’s default framing of the terrorist conflict as a religious, cultural and ideological war: a “Clash of Civilizations”. This terrible, delusional, slogan was used to radicalise and militarise the West’s response after 9/11 – with disastrous consequences.

It defined the conflict in binary, emotional, terms – “You’re either for us or against us;” “good Muslim v bad Muslim” — that made conflict more meaningful for terrorist recruits and enabled al Qaeda to claim, “Islam is under attack”. We’ve also made the mistake of focusing on radical theology as the cause of radicalisation.

This over-determined the role of religion, fuelled Islamophobia, encouraged populism and helped to drive social and political polarization. In my view, the election of Trump as President of US can be traced directly to the failed overreaction of the US response to 9/11. And any hope that the West can recover from its mistakes has evaporated with Trump’s election and his appalling appointments.

Not the ideology

It’s no surprise that we’re also using the wrong tactics by treating counter-radicalization as a kind of argument, a “Clash – or War of ideas” … as if we could debate facts, apply theological arguments and alleged western values to defeat terrorism. It’s called the “counter-narrative” and it has made things worse by drawing attention to the terrorists’ point of view, without making any impact.

We’re simply talking to ourselves. Spinoza is very clear about this: true ideas don’t have the power to remove obstinate emotions or beliefs simply by virtue of being true. And realistically, theological debate – as Spinoza would argue — has got nothing to do with truth anyway. Put simply, we can never win this argument – even when we’re right. It’s the wrong argument – and the wrong approach.

Part 4 ~ Frame the conflict as a psychological war

Part 4 ~ Frame the conflict as a psychological war

So if it’s not a “Clash of Civilizations”, what is it? Spinoza devotes a majority of The Ethics to understanding human emotions. And no emotions are more important in his politics than the interplay of hope and fear. Indeed, the elimination of fear is central to his project. He says, “a free people is led more by hope than by fear, while a subjugated people is led more by fear than by hope.” That’s our clue.

Today, he would recognize that European democracies – not the Middle East – have become the front-line in a new kind of psychological war, around the emotion of fear; fear for security; fear of Muslims and Islam; fear of immigrants; fear of refugees, fear of loss for a way of life – and most importantly, fear of uncertainty and the future. In Spinoza’s terms, all this impacts our imagination, filling us with negative, passive, emotions – anger and fear.

And we should recognize that warfare today has evolved – for all practical purposes – into knowing and understanding how to influence what people think and feel. Think of the current accusations of cold-war revivalism against Putin for his influence in the recent US elections.

Populists and IS share the same strategic objectives — to divide, polarize and radicalize our populations. We’re the front-line of this psychological war since this is where the fear of IS and its propaganda meets the amplification of domestic populism. Populists convert these fears into nostalgia for a lost past using the language of nationalism, racism and Islamophobia. They endow nativism with an almost mystical significance.

The strategic weakness of democracy is that, without strong leadership, it struggles to cope with instability and sudden movements in mass psychology. As Obama said last week – we cannot take democracy for granted. And so Western democracies become weaker and core democratic values come under attack from within. Much of this fear is hysterical and irrational. For example, a majority of Americans now think they or their family members will be killed in an IS attack. In fact, since 9/11, they’re almost 300 times more likely to be killed by a police officer – and everyday, more likely to be killed by far-right extremists than jihadists.

The result is that irrational fear has given our body politic an auto-immune disease – we’re attacking ourselves. As Spinoza tells us (in the TPT) … Every system of governance is threatened more by its own citizens than by its open enemies. And IS uses this strategic weakness to press home its psychological attack. And, by this way, populism poses a much greater threat to our democracy than IS ever could.

Spinoza’s psychology – it’s emotions — not the ideology

One of the major successes of Spinoza’s philosophy is that it provides the basis of a modern scientific psychology and psychoanalytic theory. Spinoza’s psychology places an enormous emphasis on the power of emotions to subvert everything else in human life, so let’s see where that takes us…. And let’s look at the facts…..

The terrorist ideology is weak in Europe. It’s the best-known ideology in the world yet it inspires recruits only in random ones and twos. IS has never appealed to more than one thousandth of one percent of Muslims and now says to recruits: “Don’t worry about ideology. We are the ideology. That’s all you need to know. Obey us.”

Spinoza’s philosophy shows us how the path to extremism is likely to be individualistic, psychological and, I will argue, consumerist.

Let’s consider first, the relevance of Spinoza’s insights into emotions and drives. He says, “Everyone shapes his actions according to his emotions;” and, “Everyone strives to increase his own sense of power, to seek his own advantage.” People are “conscious of their desire without knowing the causes of desire.” “True ideas are not enough to change negative or obstinate emotions.” “An emotion can only be changed by a stronger and contrary emotion.”

To summarize these powerful insights, Spinoza’s thinking teaches us that extreme acts and beliefs are expressions of extreme emotions. What people say about why they hold extreme beliefs is not reliable since they’re not aware of the real causes of their feelings. Asking a jihadist exactly why he radicalized is unlikely to reveal the truth – even if he was honest.

Every psychoanalyst knows we can vigorously defend, but secretly doubt, what we believe to be our strongest held beliefs – including the ones we say we would die for. As John Le Carré’s clever spy, George Smiley, says – “Every fanatic is hiding a secret doubt.” We need a stronger explanation for violent extremism than simply being convinced of a theological argument. Today we would not expect to help someone with an eating disorder by arguing with them about their nutritional needs. Something else, something much more profound is going on. We know it’s a psychological condition. It’s the same with our efforts in counter-radicalization.

Part 5 ~ What is the emotional attachment mechanism?

The question we now need Spinoza’s help to answer is – if theological belief is not the real cause of terrorist recruitment – what is?

First, we must understand that European jihadists aren’t driven by the same factors as MENA recruits. They’re born, raised and educated with Western rather than Sunni-Islamic values. IS is a radically violent Sunni-sectarian organization and yet most European recruits have no idea of – and certainly no grievances that relate to – differences between Sunni and Shi’ia Islam. Most are wholly ignorant of the differences. Like Protestants and Catholics in Belfast – sectarianism was an excuse for violence, not a cause.

Like everyone else, European recruits are consumers in a consumer culture, and instinctively relate to how brands use feelings and emotions to influence and communicate symbolic meaning, identity and values. They also face anti-Muslim sentiment – something that doesn’t exist in Muslim countries – so there’s already a distinct impetus in some towards finding a counter-cultural – anti-Western – identity. If we put these two things together – consumerism and search for identity – we come up with brands.

Consumerism and religion

Consumerism, as a form of identity building and attachment, has taken on many aspects of religious devotion. In the 17th Century meaning, identity and attachment were defined by religious belief, sect and congregation. Today, these are replaced by consumer desire, brand loyalty and social-media networks. In the 17th Century, the purpose of this life was to find salvation in the next; in today’s celebrity culture, many seek fame and recognition as a form of redemption. (Could we imagine Spinoza’s landlady, today, asking if she’ll be famous when he dies?)

Spinoza’s thinking tells us to follow the emotions. Unlike theological arguments which deal in ideas, opinions and abstractions, brands quickly communicate powerful emotional stories that appeal to fantasies of power, identity and a sense of belonging. Because they appeal to unconscious emotions, people identify with – or reject – brands for reasons that are close to love or hate – feelings that they cannot explain rationally. As the poet says, “The heart has its reasons, of which reason knows nothing.” In Spinoza’s words, we are, …“conscious of desire but not the hidden causes of desire.”

In the “Korte Verhandeling” Spinoza writes, ”We could not exist without enjoying something with which we become united and from which we draw strength.” As we shall see, for the European jihadist – where the radicalization process has become faster and faster — the union he draws strength from is not Allah, or the worldwide umma, or the Caliphate, but the powerful “fast-food “ – the instant gratification – of the “off-the-shelf” jihadist brand. In this way, he buys into IS as a consumer rather than as a genuine religious believer or convert.

The IS brand

This doesn’t happen by chance. IS projects its carefully managed brand package into the West to target alienated desire and lost identity — preferring recruits who have a violent criminal background – and almost 70% have. There is no battle of ideas on the part of IS or genuine effort to convert – simply a push for media exposure and connection.

It’s a symbiotic relationship. The IS brand narrative offers a transformed life – a second chance: a sense of victimhood redeemed; becoming a player in a world-historical struggle and the promise of recognition that means, in the end, his life can be a success – a marriage of victimhood and celebrity. This is Western, not Islamic: a diet based on the values of reality TV, Hollywood revenge movies and social media profiles. And they’re fixated by all of these.

Even Spinoza – in the 17th Century – recognized the devious attraction of the all-too-human weakness for fame. And in terms of branding strategy, it’s exactly how the Trump campaign operated – all emotion and unspoken fantasy, an imagined, shared backstory, vague promises of greatness but lacking genuine ideological content. It works.

The point is, none of this requires belief in – or even the existence of — an ideology. Western recruits aren’t being pulled-in by theological argument, but by their imagination and a series of passive emotions and empowering fantasies. The ideology today can be reduced to shouting “Allahu Ahkbar”, and is simply one more branded product – like the black flag, a ski-mask, an unopened copy of the Koran (or, if you’re French, the burkini).

If we look at this through the lens of Spinoza’s theory of emotions we can see the mechanism of radicalization more rationally – it’s about a mess of emotional needs and drives being matched by carefully crafted fantasies of meaning, identity, purpose, revenge, and fame.

Part 6 ~ Fear, superstition, uncertainty and Amsterdam

Social cohesion has become hugely important in preventing community radicalization and maintaining state security. In this regard, the actions of populists driving polarization by manipulating public fear are a direct threat to our security. This is why IS celebrated the election of Trump.

Spinoza recognizes that public fear of uncertainty causes conflict and breaks social cohesion – and that people who swing wildly between hope and fear can believe almost anything. He argues that political and religious rulers took advantage of fear of uncertainty to impose standardized and manipulative belief systems. Fundamentalists and populists exploit fear of uncertainty in a self-defeating way – namely, they need to encourage fear if they are to stay relevant. It’s ironic that they quickly produce too much certainty – that is, intolerance and instability.

Spinoza knows uncertainty can be a negative force yet he offers a radical solution – not “How can we remove it?” — (we can’t) – but how can we use it to help improve social interaction. I think he learned something very important here from his experience as a merchant in Amsterdam.

The city’s cultural DNA is rooted in an independent – pragmatic – state of mind, a product of internalizing the habit of negotiation from trade, and trust in commercial procedures, together with the cooperation inherent in the polder model.

Rather than fear of uncertainty, Amsterdam’s citizens used “constructive uncertainty” and risk-management as a way to increase interaction by negotiating their everyday practical certainties. In this way, the positive interplay of hope and fear enabled them to embed core democratic values – in particular, pluralism, tolerance of “The Other” and a skepticism towards the brittleness of fundamentalist thinking. The key was the development of the flexibility inherent in the democratic mindset.

At the core is the realpolitik of compromise and this, Spinoza recognized, goes to the heart of the democratic process – surrendering our natural rights to gain freedom from fear and the security of state protection. It’s a win-win situation for citizens and the state, and fundamentalists and extremists, simply cannot do this. They have to win on their terms only – and everyone else has to lose. This is simply not the Amsterdam way.

In terms of cooperation, Spinoza tells us that people “… without mutual help live miserable lives….life (he says) should not be controlled by individuals, but by the power and will of everyone….and…. Men ….. should defend their neighbour’s rights as their own.”

He also saw that the politics of group identities are both divisive and destructive of individual freedom and social cohesion. Spinoza was more focused on defending and protecting individual freedoms than the freedom of organized religious worship.

Towards the end of the TTP, Spinoza describes how the relationship between freedom, tolerance and the state will work. He’s not describing an abstract idea or Utopian vision. He’s writing about the Amsterdam he knew and loved. He says, “In this thriving and splendid city state, people from all nations and with all possible beliefs live together harmoniously… religion and sect are of no importance for it has no effect before the judges in winning or losing a cause…”

In this way, the city’s cultural DNA plays an important role in enabling Spinoza’s emphasis on social cohesion and how it relates to counter-radicalization.

Part 6 ~ Finale

I want to finish by briefly mentioning two aspects of his life that are important for how we remember him.

For Spinoza, the social class, religion, nationality or ethnic group we are born into has no intrinsic value, because, as he puts it in The Ethics: “All men are born ignorant of the causes of things.” Life is a process of becoming – a struggle to see what you make of yourself — and we all have exactly the same hill to climb.

Spinoza was given the name Bento at birth. So far as we know, he never referred to himself as Baruch. We do know that from the age of fourteen he signed and called himself Bento. With his name change – from Bento the Merchant, to Benedict/us the philosopher – he quite deliberately re-invented himself – sometime in his mid-twenties – for the next phase of his life – and it was a philosophically significant moment. It was about much more than a name. It was an entire identity — a brand – complete with a motto – “Caute” – and the symbolic logo of the rose.

He now belonged to Mankind, transcending the passive accident of birth. We should respect his decision and refer to him by the only name he ever chose for himself, that he used in his correspondence and conversation with others, and took with him to the grave. He signed his name – Benedict de Spinoza.

I want finally to focus on one feature of Spinoza’s life that is truly inspirational. He had courage. As a young man, he stood up to the bullying of his community to conform, and in later life he endured attacks and abuse from the equivalent of today’s far-right populists and ecclesiastical bullies. With the murder of the de Witts he experienced the destructiveness of populism and violent extremism. It did not stop him protesting it.

What is impressive is his inner-strength and courage even as he became weak and sickly. He argues that often it is the wisest and most peace-loving who are the targets of moral crusades and intolerance and just as often, it’s the stupidest and most obnoxious who lead such campaigns. Are you listening Geen Stijl?

I talk to people today who feel intimidated by populists, idiot commentators and cowardly bloggers. When we remind ourselves that in the space of a few years, four people close to Spinoza were executed, murdered or died in prison because of what they believed, what we face today is nothing by comparison.

I think he would be a bit alarmed at the way the democratic centre is under pressure today but I also think he would immediately clear his thinking and get on with the fight to protect democratic values. And so must we.

Forty years after I first began to read Spinoza, he is still a ghost in my life, and standing here today, he seems closer than ever. Time has no real value in Spinoza’s philosophy – nothing, he says, is more perfect for living longer.

And speaking of time, I’m sure there are many in this room who would gladly give up a year of their life to have the privilege of spending just one day in conversation with him — in the beautiful city of Amsterdam.

Thank-you for listening, and the privilege of speaking to you today.