Terra Firma: Ashore in the Bay of Strangers

Friday, 25 August 1995 – “Bosun – topside!” The Captain’s command over the intercom aroused me from a deep sleep. Henri, jumping from his cot, rushed out to film the action on deck. Soon the muffled rattling of the anchor chain reverberated throughout the ship: we were dropping anchor. Slowly, I got up. Fleetingly, ever so fleetingly, a wave of revulsion suffused my body, and I tried not to think about what was outside: a fog-shrouded, ice-cold sea and a huge, empty island. I glanced at my watch: 7:15 a.m. Through the porthole I could see a calm sea, light blue under a low, grey sky. If this was Ivanov Bay, the grave search party would go ashore. If it wasn’t, only the Captain might know where on earth we may be. I got dressed and hurried outside. In the light, drizzly mist that engulfed the ship, Jerzy and Bas were siphoning gasoline into lemonade bottles from a big, rusty fuel barrel on the foredeck, using a rubber hose. Inside, the breakfast table had been set, but there was no time to eat. The landing of the grave-searchers was busily being prepared, as Boyarsky was threatening that the sea might soon get rough again. Only George, with aristocratic unconcern, sat sipping a cup of tea in the otherwise empty mess room. The corridors teemed with foot traffic. The hum of electric motors resonated through the steel vessel as the deck crane deposited a huge stack of wooden beams and planks from the hold into the landing craft. For protection against bears, the Ivanov Bay group would be constructing a hut for their stay. On deck, the atmosphere was frenzied and tension was palpable, with good-byes adding to the din of cargo handling.

Friday, 25 August 1995 – “Bosun – topside!” The Captain’s command over the intercom aroused me from a deep sleep. Henri, jumping from his cot, rushed out to film the action on deck. Soon the muffled rattling of the anchor chain reverberated throughout the ship: we were dropping anchor. Slowly, I got up. Fleetingly, ever so fleetingly, a wave of revulsion suffused my body, and I tried not to think about what was outside: a fog-shrouded, ice-cold sea and a huge, empty island. I glanced at my watch: 7:15 a.m. Through the porthole I could see a calm sea, light blue under a low, grey sky. If this was Ivanov Bay, the grave search party would go ashore. If it wasn’t, only the Captain might know where on earth we may be. I got dressed and hurried outside. In the light, drizzly mist that engulfed the ship, Jerzy and Bas were siphoning gasoline into lemonade bottles from a big, rusty fuel barrel on the foredeck, using a rubber hose. Inside, the breakfast table had been set, but there was no time to eat. The landing of the grave-searchers was busily being prepared, as Boyarsky was threatening that the sea might soon get rough again. Only George, with aristocratic unconcern, sat sipping a cup of tea in the otherwise empty mess room. The corridors teemed with foot traffic. The hum of electric motors resonated through the steel vessel as the deck crane deposited a huge stack of wooden beams and planks from the hold into the landing craft. For protection against bears, the Ivanov Bay group would be constructing a hut for their stay. On deck, the atmosphere was frenzied and tension was palpable, with good-byes adding to the din of cargo handling.

Freed from all its cables, our landing craft, a red steel barge five meters long, danced merrily atop the waves. Once the entire Ivanov gang had climbed down the rope ladders, the droning plashkot sailed rapidly into the haze. Bundled up in gear as if ready to go ashore myself, I stood in a light rain atop Kiriev’s bridge and followed the progress of the landing through binoculars. A trio of long, rustbrown walruses glided by the red craft through the pale blue sea. It was easy to distinguish their bristling snouts, which spit out a spray of condensation and water when the animals are surfacing. It was +4°C. Novaya Zemlya was just a dark strip of land, the elevations above ca. 100 m disappearing into the low clouds. There was little snow.

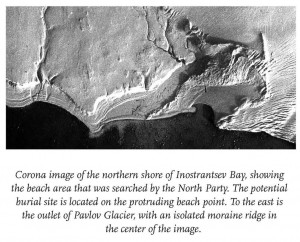

By 11:15 a.m., the Ivanov group was ashore. The landing craft delivered a second load and was hoisted aboard. Kiriev raised anchor, but would not sail towards Ice Harbor. It had been decided to seek shelter from a new storm in Inostrantsev Bay, on the west coast of the island. Excitement swept over the ship when, at noon, we saw the first unobtrusive iceberg float by: the entire oyage so far had not provided this many sights. The silent flotilla of blue sculptures grew by the hour, indicating the proximity of calving glaciers. Our arrival in Inostrantsev Bay was estimated for 3:00 p.m. The plan calls for a reconnaissance sortie with two groups along the beaches of the bay, to search for cairns. Boyarsky requests that we be specifically alert for objects indicating the presence of the ancient Pomors and the Nazis, who operated in greatest secrecy on these shores during their Arctic campaigns. The approaching landing put us back on the alert. Bas distributed ammunition for the rifles and reviewed the arms discipline. “Should a polar bear come after us and we decide to fire at him,” he instructed us, “we’ll follow our firing-range routine. The shooter kneels down and someone else counts the bear’s approach: fifty meters… forty meters… thirty meters… Don’t stare at the bear, but focus on his chest or on his shoulder. There will be three cartridges in the magazine. For reasons of safety, do not keep a cartridge in the chamber. Remember, the second man keeps additional ammo at the ready.”

Self-sufficiency is imperative for one venturing out in the Arctic, and it was high time to get my gear in order. (“Coming along?” Anton, our film director, would tell the viewer. Small kids start crying, young women turn off the TV.) What do I need? After polar bears, the unpredictable weather, which can change from quiet to severe in half an hour, is the greatest challenge. The land is barren and provides no shelter. There is no snow in which the stranded traveler could dig a shelter against the piercing winds. To be lightly equipped and able to move about swiftly, I packed the thin, reinforced Gore-Tex cover of the Navy-issue sleeping bag and a small stove, with a one-liter bottle of gasoline, enough for two weeks. High-grade gasoline is harder to come by in these parts of the world than diesel or kerosene but more practical because kerosene fuel oil has a flash point well above 40°C and won’t ignite easily in low-temperature environs. I took my down jacket, wrapped in a plastic bag, so I could leave my sleeping bag on board. I took wax for my boots, packages of instant soup, chocolate milk, and mashed potatoes. There would be sufficient meltwater on land, but just to be sure, I filled my canteen. On a waist belt, I carried the dagger and a pouch containing flare gun, GPS, a set of waterproof-packed batteries, a notebook with waterproof paper, and a pencil. I took some extra film and decided where to put everything: the rain gear fortunately has plenty of zippered pockets to stow away the many little items I need to keep track of.

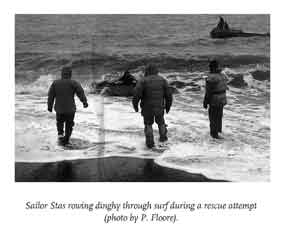

The sea was calm: smooth as glass. The landing craft glided over in fifteen minutes and at 4:00 p.m. ground onto the steep, gravel beachfront. The sailors kept the engine running to maintain a solid lock while we disembarked. In clouds of smoke and steam, we climbed the steep ridge of loose gravel. Then, after reversing the propeller’s motion, the plashkot quickly retreated into the fog.

A steep bluff, tall and dark, disappeared on either side of us into the mist: the Edge of the World. Gigantic whale vertebrae lay scattered across the beach. Large blocks of ice swung in the surf. The group split without losing time and five men started off toward the southeast. The other team would move northwest. We gathered the life vests in stacks, then covered them with heavy boulders and lengths of driftwood. The north team, which includes Jerzy, Yuri, Dirk, Mark and me, spread out over the ~200 m wide beach. The bluff denied us a view into the interior, and I quickly considered how much it would take to conquer the obstacle. As I approached the slope, I discovered that it is barely 50 m tall. Each step lessened the elevation; the ground seemed to be falling away beneath my feet. As I neared the cliff edge and saw inland, my elevation above sea level was approximately 15 m, and I could begin to see the dimensions of this world. Altitude and distance are difficult to estimate in an empty landscape. Most people would find this environment intimidating and depressing. Down on the beach, Jerzy called and gestured and I came running back. “No more of that puppy-like behavior!” he said angrily, as I, panting, resumed my position. One must feel the landscape. Fine, grainy debris fans across the plain. The ground consists of sharp, slaty sandstones, characterized by thin smooth plates and shiny slivers, which break down to sand-size fragments. Patterned ground indicates the presence of permafrost: half a meter down, ground temperatures never rise above 0° C. Summer thaw of the upper soil has caused flat slabs of rock to sink and stand at odd angles, like headstones in a graveyard. Patches of moss, which needs phosphates, often form around decaying whale bones or large bird carcasses. One such patch was rectangular and had the approximate dimensions of a burial. Jerzy assembled the metal detector and surveyed the moss. No signal. He shrugged and we moved on. We tossed each other an oversized rubber wader to cross a stream.

After walking for two hours, we arrived at a promontory and in awe observed a blue glacier tongue loom through the fog. The calving front is like bright blue marble, rising from the sea a sheer fifty meters. Every now and then, large slabs collapse from the glacier with a roaring noise. This fills the bay with larger and smaller icebergs, which, in the absence of wind, float around randomly. Jerzy nodded, “If you, sailing along the coast, wanted to bury somebody… where would you do that?” We looked around and spotted a collapsed cairn nearby. The stack of rocks was about 1.5 m across and could easily cover a grave. To our surprise, the detector gave a loud and clear signal. There was a metal object underneath the cairn, which might well have been put together as a navigational aid by Norwegian or Russian hunters. It could be a button, or a ring, or a bullet. Often, those building a cairn would leave a message in a pewter can or inside a soldered bottle.

Unfortunately, we ran out of time and within a half hour would have to move back to the landing zone to meet the plashkot. The GPS measurements came through and I read the coordinates to Dirk. Our reporter, Mark Glotzbach, was scribbling along and we asked him not to put this in the paper. While the others prepared a quick sketch of the cairn, I joined the two Russian geologists who had caught up with us. They established the limits of a rock outcrop marked on the geological map. Skeletal remains were spread all over and there were reindeer tracks. I stumbled across three enormous polar bear skulls, one with a bullet hole. Water rose to my ankles in a muddy stream where I photographed a heavy wooden construction that must have washed ashore during a storm. A steepsided moraine, possibly indicating the glacier’s extent in Barents’ time, stretched inland. Along the high-tide line lay unimaginable numbers of beached aluminum and plastic floats, shampoo bottles, cleaning brushes, plastic detergent containers, polyethylene rope, nets, fish-boxes, and other fishery material: the garbage that is carried on the poleward-flowing North Atlantic ocean current.

I expect that Ice Harbor will get less detritus. “Coming along?” said Jerzy when our team zippered up and prepared to head back. “We’ll come back later for this one.” The clouds had lowered and a fine rain swept across the beach. In a chilly dusk we started walking. When we got back to our landing site, I was thoroughly soaked from the continuing drizzle. The north group had returned earlier. It is a raucous gang!

The ship’s doctor was shooting at boards and crates set up by his assistant. The homemade gunpowder created a huge cloud of smoke with each shot. Another nut was firing green flares into the clouds to attract Kiriev’s attention, but I had a hard time believing that the vessel, anchored about a kilometer offshore, could see the fireworks. He then shot a wide-barreled handgun, and an enormous, yellow flare bathed the layer of fog in a threatening glow before arching into the sea and a flickering death. The Russians are very amicable and again liberally poured vodka around a big fire. The drinks hit mercilessly. Tired and chilled, I could feel my cold, sweaty shirt stick to my back. Snowflakes mixed with the rain.

For this absurd beach festival, we had abandoned our research, for which neither cost nor effort had been spared. We stuck to the rules and came back at the agreed upon time – it’s only the decent thing to do – and we were paying the price. The doctor finally blasted the case to smithereens. So much for the firearm discipline, too. The spectacled Badyukov brothers, Dmitri (Dima) and Daniel, then asked if I knew the joke about a Dutchman, a Frenchman, and a Russian on an uninhabited island, and I let go of my resistance. We must just go along as things have been going here for centuries. “A Russian, a Frenchman, and a Dutchman are stranded together on an uninhabited island,” the joke began. The vodka was stinging in our mouths. “They had to find means to survive and walked along the tide line in search of anything useful. The Frenchman found a bottle of wine; the Dutchman, a bottle of whiskey. But the Russian found a rare jar. They decided to open the jar first. As soon as the Russian pulled the cork, a spirit appeared, who said ‘I am the spirit of this jar’ and invited all three to make a wish. The Frenchman looked at his watch and said ‘Now that it is six o’clock, I would like to be with my wife.’ And he disappeared! The Dutchman thought for a few moments and then asked the ghost to whisk him off to a grand hotel. He, too, was gone. Now, it was the Russian’s turn. He looked sad and said to the ghost, ‘I just had two buddies and two bottles to empty with them.’” Daniel, who was presenting this joke, paused contentedly and stared into the flames before continuing: “‘And now,’ the Russian said, ‘I have only this empty jar. I wish that they would return!’” The brothers laughed uproariously. “So you see,” says Dima, “it won’t help to wish yourself away from here.”

The vodka pouring had caused a brief intermission in the activity of that flareshooting grey mouse, who now resumed his effort to draw the ship’s attention. Each flare went up with the sound of a firecracker. It was making everyone jumpy. Clearly, he wished to be taken off the island, and I, too, had had my share of socializing. Not a moment too soon, Jerzy tossed his cigarette butt on the ground and pulled a radio from his pocket to call in the landing craft. Half an hour later, at 10:15, our salvation emerged from the dusk. The return to Kiriev was ice cold but indescribably beautiful. People were silent, tired and intoxicated to the point of exhaustion. The fire on the beach rapidly turned into a small orange light and then vanished into the fog. The sea was a light blue, with widely scattered icebergs, silent and still. It is difficult not to see all kinds of images in the melted, clear-blue or crystal-clear ice shapes: knights on horseback, gruesome figureheads with mute, frozen screams on their faces, grotesque monsters, gargoyles, and dragons. Pieces of transparent and molten ice floated past the sides of the plashkot, crackling sharply like ice cubes in a glass of lemonade. The deckhand hung across the bow signaling port or starboard to the helmsman as we maneuvered through the bergs. Kiriev continued to remain out of sight. Four hundred years ago, off this same coast on their return voyage, the two sloops of winterers fired muskets to find each other in the dense fog (26 June 1597). The helmsman got on the radio several times. Because the vessel could not see us either, I assume he received directions based on Kiriev’s radar. In any case, a weak glow soon appeared in the fog.

Kiriev turned on all lights: a magnificent show. We were silent; I was struck by size of our ship. Our safe, warm base appeared terribly small, yet ingenious, floating on the vast sea under that great, impermeable sky. After a good fifteen minutes, which seemed endless, we docked alongside the vessel and climbed aboard by a rope ladder. In heavy weather, as we noticed on another occasion, the crew drops a large mesh alongside, which you must grab onto at the crest of a wave. To counteract the waves, the ship turns into the wind like a mother swan of steel. The crew works smartly and fully focused, and as soon as they can grab you they’ll hoist you aboard in one swift motion. When all had boarded, the crane lifted the landing craft onto the deck, cargo and all. In the mess, it turned out, dinner was waiting. Anton sat across from me.

“So…” he pushed his chair closer, “a delicious soup!” He rubbed his hands, grabbed the spoon and carefully slurped the yellowish, salt water. The kitchen staff was already setting out the next dish: potatoes and black-fried liver. The soup gone, Anton looked at me. “Marvelous, right, all those frost-shattered rocks?” While he was talking, I thought of Pieter and Dr. Maat. How are they doing? They are sitting like princes with Eugene, Konstantin, Vitali, and Nicolai in their small cabin, surrounded by silence. Meanwhile, my research time is being nibbled at from two sides. Every day spent at anchor is critical; we already knew that. Now, it also turns out that Starkov has to be back in Moscow on 14 September, to catch the monthly flight from Moscow to Spitsbergen. He expects us to drop him off well before that at Amderma, on the North Russian coast.

This puts our schedule under enormous pressure. Starkov looks grimmer by the day, and we’ll have to use our time at Ice Harbor to the fullest to get the work done. Thus, it becomes almost impossible to journey inland. This is quite a blow, but better not piss and moan about it, for I, too, will have to strain to complete my tasks.

Saturday, 26 August 1995 – After some five hours of sleep, I awoke at 7:00 a.m. and dressed for a landing near yesterday’s find. Instead, I soon found out, we will sacrifice another day. Boyarsky doesn’t want to risk our getting stuck on land if the weather suddenly deteriorates, and they have denied our survey ashore. This I take with a healthy mistrust. The Russians appear to have an agenda of their own. Even the trip to Ice Harbor is being delayed and we apparently are awaiting the arrival of a storm in the confines of the bay. “Just get some rest,” Jerzy said comfortingly. “When the action comes, it’ll be fast.” I hung my waders to dry and rubbed them free of Novaya Zemlya’s glittering black sand in one of the ship’s corridors. As the heavy steel door clanged hermetically shut behind me, I sauntered whistling to the mess. The Captain, just coming down the stairs, put a finger to his lips. Embarrassed, I covered my mouth with my hand. Lore of the sea says that whistling aboard ship invites calamity. In the mess, I found Dr. Labutin and when he saw me, he jumped up and signaled me to come along. He’s quite a character! George told me that Labutin is almost 50 years old, but he looks like a caricature of the Russian medical student: tufted hair; horn-rimmed glasses; threadbare, checkered shirt with even the collar buttoned; and a brown knitted pullover. I followed him through the narrow corridors. Last night, bored, I had pasted one of the fake kiddy tattoos that Philips Electronics sent along with the batteries onto my chest. Once you’re under his care, Dr. Labutin won’t even look you in the face. He’ll pull your T-shirt out of your pants and only has eyes for what the meters indicate. But now, when he pulled my T-shirt up to place an electrode over my heart, he read “Kiss me” and a grin appeared across his face. Weight: 71 kilograms. Blood pressure: 75/180 (“Only if you see a girl walking down the street can it be somewhat higher,” says Dr. Maat). And then he signaled me to get on the bicycle again. The porthole was open and I could see icebergs. A good-sized, blue berg lazily floated by, scraping the side of the ship. I thought back to Amsterdam; the city hadn’t defeated me. I had only been there a short while and lived in a deserted warehouse on the quays of the IJ River. At nights, when I had trouble falling asleep, I would walk into town. Outside, further down along the dark building, I would see the outlines of girls in high heels, a purse across one shoulder, against an endless stream of headlights. Some nights, there were a hundred of them “working” and when I came home, they asked for cigarettes. Because of the solitary smoking and drinking, I wasn’t in such great shape two months ago, when I entered Gawronski’s basement office, but my strength quickly returned. When I had pedaled enough, Labutin gestured again and I sat up straight to look at the dial indicating my pulse. The doctor was satisfied. I could go now.

Saturday, 26 August 1995 – After some five hours of sleep, I awoke at 7:00 a.m. and dressed for a landing near yesterday’s find. Instead, I soon found out, we will sacrifice another day. Boyarsky doesn’t want to risk our getting stuck on land if the weather suddenly deteriorates, and they have denied our survey ashore. This I take with a healthy mistrust. The Russians appear to have an agenda of their own. Even the trip to Ice Harbor is being delayed and we apparently are awaiting the arrival of a storm in the confines of the bay. “Just get some rest,” Jerzy said comfortingly. “When the action comes, it’ll be fast.” I hung my waders to dry and rubbed them free of Novaya Zemlya’s glittering black sand in one of the ship’s corridors. As the heavy steel door clanged hermetically shut behind me, I sauntered whistling to the mess. The Captain, just coming down the stairs, put a finger to his lips. Embarrassed, I covered my mouth with my hand. Lore of the sea says that whistling aboard ship invites calamity. In the mess, I found Dr. Labutin and when he saw me, he jumped up and signaled me to come along. He’s quite a character! George told me that Labutin is almost 50 years old, but he looks like a caricature of the Russian medical student: tufted hair; horn-rimmed glasses; threadbare, checkered shirt with even the collar buttoned; and a brown knitted pullover. I followed him through the narrow corridors. Last night, bored, I had pasted one of the fake kiddy tattoos that Philips Electronics sent along with the batteries onto my chest. Once you’re under his care, Dr. Labutin won’t even look you in the face. He’ll pull your T-shirt out of your pants and only has eyes for what the meters indicate. But now, when he pulled my T-shirt up to place an electrode over my heart, he read “Kiss me” and a grin appeared across his face. Weight: 71 kilograms. Blood pressure: 75/180 (“Only if you see a girl walking down the street can it be somewhat higher,” says Dr. Maat). And then he signaled me to get on the bicycle again. The porthole was open and I could see icebergs. A good-sized, blue berg lazily floated by, scraping the side of the ship. I thought back to Amsterdam; the city hadn’t defeated me. I had only been there a short while and lived in a deserted warehouse on the quays of the IJ River. At nights, when I had trouble falling asleep, I would walk into town. Outside, further down along the dark building, I would see the outlines of girls in high heels, a purse across one shoulder, against an endless stream of headlights. Some nights, there were a hundred of them “working” and when I came home, they asked for cigarettes. Because of the solitary smoking and drinking, I wasn’t in such great shape two months ago, when I entered Gawronski’s basement office, but my strength quickly returned. When I had pedaled enough, Labutin gestured again and I sat up straight to look at the dial indicating my pulse. The doctor was satisfied. I could go now.

The wind turned to the northwest, so that Ice Harbor was now in the lee of the island, but was this a stable situation? At night the weather forecasts from Dikson, Murmansk, and a German station still contradict each other. The clouds had lifted somewhat, providing us with a better view of the Inostrantsev Bay. Through binoculars, I observed the landscape that we had traversed yesterday.

The plateau slopes towards dark mountains of ~300 m, behind which lies the ice cap; still hidden in clouds. In the southeast, the calving fronts of glaciers rise from the waters of the fjord. At the dark horizon of the Barents Sea are a number of small, rocky islands. I urged Jerzy to get us ashore in Ice Harbor at any cost. In my opinion, now that we have come so far, we should risk a bit more to go farther. This crew is restless and complaining.

Working in the Arctic has a frustratingly low effort-to-yield ratio, and most days are spent waiting and watching. For this, we invested years of our lives; I see the stack of scientific papers we’ve carried along and know the methods and instruments at our disposal. More people have been up Mount Everest than on Cape Spory Navolok. We are prepared and standing by. Jerzy called the researchers together to give them an accounting of this totally lost day. It is insane that we have been killing time lying at anchor in a flat sea and calm weather, only a stone’s throw from our once-remote goal. Why did they not allow us ashore? “We’ve all been somewhat frustrated by today’s events,” Jerzy started.

“The ship’s lying at anchor is the Captain’s decision. Here we have a good anchorage. Off Ice Harbor, Kiriev will have to cruise under difficult circumstances. That will cost fuel, fuel that we need to wrestle our way back to Archangelsk. We didn’t schedule a landing today because we can ill afford to have five men ashore for five or six days. The point is: this plashkot is unstable if the swell increases. This morning, we were all ready for it, but I declined to congregate on deck in full gear because this would be much more demoralizing, especially if we have to repeat it several times. Should the situation remain unchanged, then we can say back home in the Netherlands that we were ready but unable to do anything. We are now supporting the Ivanov group. They will have to work for us. Looking at it this way, we have made pretty good progress in the ten days that we have been underway: the search for Barents’ grave was landed and we were able to investigate the west coast. We are still working towards our schedule. By midway next week, that will be different.” “Then we will be working off our schedule, I think,” Bas grinned.

“Any questions?” No questions. We discussed the possibility of landing a small team the next morning: Jerzy, two Russians, Herre Wynia, and me. At least, we could investigate what triggered the metal detector. Even though we were anchored offshore of Novaya Zemlya, our destination seemed farther away than ever. No one would say so out loud, at this stage, but I could not exclude the possibility that we would fail to reach the Saved House.

With Kiriev still lying at anchor in rough Inostrantsev Bay, engines shut off, I gazed at the walls of ice, black rock formations, and inert blue icebergs. An eerie pewter-grey overcast surrounded us. There was no sign of life: the vast bay appeared frozen in time. I shared a weird concoction with Herre, Vadim Starkov, and Victor Dershawin, who brought it with him. A genuine Che Guevara poster decorates the wall of Herre and Victor’s hot cabin. The pungent odor of perspiration, garlic, and booze is made bearable only by Herre’s constant stream of rolled cigarettes. Jerzy came down earlier and told us that a strong cyclone is approaching and we must wait for it to pass: perhaps three days. We accepted his announcement without any reaction. Later on, lying pensively in my berth and feeling tired and not too good, I heard the anchor chain rattle throughout the vessel as it was being hauled in. “They’re hoisting the anchor,” I said to myself, sitting up. “What are they up to now?” I looked into the cabin across the hallway. Starkov shook his head, saying in halting German that it couldn’t be the anchor. Yet within a short time, the ship was buzzing with activity and the engine started. The vessel had awakened!

The decks were vibrating again. The hydraulic system was pressurized, and water fell clattering along the decks. The Captain’s commands echoed through the corridors and sailors ran to duty. I stowed such loose items as drinking glasses, clothing, pens, books, and cassette tapes, and then hurried topside. As Kiriev began to move, a blackish sky hung over the clear-white dome of the ice cap. It was beautiful with that light blue sea. The wind was blowing past the ship as if sucked from a northerly direction. I learned that forecasts from three weather stations had differed, leaving a “window of opportunity.” Jerzy, Boyarsky, and the Captain decided that it was all or nothing now and shook hands for success. We can outrace the depression and will not waste one moment more. The course around north Novaya Zemlya will take approximately eight hours. It is 10:15 p.m. In the middle of the night, we will sail past Ivanov Bay.

Sunday, 27 August 1995 – Six o’clock in the morning and awakened by the sun, which shone in my face through the porthole. A calm sea, and the ship was slicing through it at high speed toward the south. Not a cloud in the sky. The landscape of northeast Novaya Zemlya showed as a vast, light-brown expanse, slightly undulating and molded by glaciers. There was hardly any snow. The ice cap, some twenty kilometers inland, was undistinguishable through the haze on the horizon. Nothing could stop us now. I couldn’t keep still and moved around excitedly as Kiriev decreased speed. 8:00 a.m. The vessel on which we left Archangelsk dropped anchor in the wide semicircular bay christened “Ice Harbor” 400 years ago. Cape Spory Navolok is a low and virtually flat headland.

The calm sea sloshed against a narrow, icy edge along the shore. Feverishly, we gathered crates, boxes, our instruments, and backpacks on deck. “I told you!” said Jerzy proudly. “When the action comes, it comes fast!” Then, the first man climbed down the rope ladder into the plashkot. Boyarsky at the railing blessed everyone going overboard with a good-luck kiss. “Dawai!, he called out hoarsely, “Dawai!”: Let’s go, let’s go!

“Just focus on Jerzy!” Anton yelled out to his cameraman, his voice breaking, as the plashkot drifted away from Kiriev. Hands shaking, I fastened the Dutch banner and the blue Russian Navy cross with duct tape to a red-and-white surveying pole. As we gathered speed and slid across the water, the banners unfurled and flapped in the wind. The ship’s crew applauded and waved goodbye with raised fists. The high door of the landing craft limits sight, so I could not gauge our progress. I asked Hans Bonke, who was here two years ago, how wide the beach is and if it is easy to climb the plateau. “You just walk right up to it,” he said. Suddenly, the shore loomed up close. Kravchenko’s cross showed thin, in sharp contrast to the clear sky. Carefully, the fully loaded landing craft wended its way across the shoals. Fifty meters to the beach.

The promontory’s beach is an undulating field of dull brown gravels, about 150 meters wide and slightly inclined toward a low rocky cliff that blocks the view inland. The tide line was a few meters away when the craft almost came to a halt to keep from running aground. Seconds were passing like cold syrup through a funnel. Then we heard the crunch of steel on rocks. Jerzy and I jumped into the surf, and I made my way across the beach. “This is it,” I said to myself, “this is it.”

I came ashore at Cape Spory Navolok on 27 August 1995, at 10:00 in the morning. There are shouts behind my back and sounds of excitement, with the gentle swash of the sea on the beach gravels. I feel very comfortable now that we have made it this far. I took in the surroundings for a few moments while the expedition’s cargo stacked up along the high-tide line. Then, with my heart in my throat, I headed for the rocks. I could barely make headway strapped into the life vest and heavy boots. Gasping for breath, I struggled against the escarpment. As soon as I could peer over the edge, I searched the flat, grey terrain for polar bears. The landscape was empty. The beams of the Saved House didn’t catch my eye directly. Behind the cross, now really just in front of me, stretched a field of small wooden spikes. This is the grid that was left behind after the excavations of 1993. In the far distance, the hills of Novaya Zemlya shone in the weak sunlight. Along the tide line, the landing craft was hastily being unloaded. Very much content, I walked back, freeing myself of the life vest along the way. We made it after all.

—

About the author:

JaapJan Zeeberg (Rotterdam, 1967) is a physical geographer with a Ph.D. from the University of Illinois at Chicago (2001). He studied the effects of climate on coasts and landscapes. After moving to the United States in 1996 he carried on with glacial-geological expeditions to Novaya Zemlya in 1998 and 2000. Zeeberg also participated in the search for remains of ‘Liefde’ in the Strait of Magellan (Chile, January 1998). His latest expedition was a five person U.S.-Russian-Swedish survey of the interior of October Revolution Island, Severnaya Zemlya (August 2003). Currently with the Netherlands Institute for Fisheries Research.

JaapJan Zeeberg – Into the Ice Sea – Barents’ wintering on Novaya Zemlya: A Renaissance voyage of discovery

Rozenberg Publishers, Amsterdam, 2005. ISBN 978 90 5170 926 1