The Kingdom Of The Netherlands In The Caribbean. The Kingdom Charter (Het Statuut): Fifty Years In The Wilderness

In this paper[i], the author will approach Kingdom relations from a socio-historical perspective. The point of departure is, as one writer puts it: ‘The Caribbean was the least exotic, the most Europeanized and the least deserving of independence’.[ii] An analysis of the socio-historical factors underpinning the Kingdom then leads to the conclusion that the only two islands to achieve Separate Status in the Caribbean, Anguilla and Aruba, only achieved it by violence, or the implied threat thereof. This leads to the final conclusion that the present approach of conferences and papers will, taking the past into consideration, probably not lead to the desired constitutional changes. The aimless wandering in the desert will persist.

In this paper[i], the author will approach Kingdom relations from a socio-historical perspective. The point of departure is, as one writer puts it: ‘The Caribbean was the least exotic, the most Europeanized and the least deserving of independence’.[ii] An analysis of the socio-historical factors underpinning the Kingdom then leads to the conclusion that the only two islands to achieve Separate Status in the Caribbean, Anguilla and Aruba, only achieved it by violence, or the implied threat thereof. This leads to the final conclusion that the present approach of conferences and papers will, taking the past into consideration, probably not lead to the desired constitutional changes. The aimless wandering in the desert will persist.

During a conversation some time ago à propos of Separate Status, former island council member, and prominent St. Maarten businessman Vincent Doncker flatly stated: ’unless we are prepared to fight and shed blood for separate status it will not happen’. This seminar from that perspective is itself questionable. Constitutional change is fought for with blood and bullets, not polite lectures and garden parties. One of the most insightful comments along that line came from dr. Nilda Arduin. ‘All the reports’ she stated, ‘will not accomplish anything unless there is a change of mentality and people really start to want and desire constitutional change’. Along those same lines, Drs. Leopold James of the St. Maarten Nation Building Foundation has persuasively argued that before separate status, or for that matter, any status can be achieved, there must be a process of Nation Building. By this, James means to say, a desire of the people to identify themselves as a separate people or nation, distinct and apart from others. Unless this desire is stimulated and nurtured, the population will remain apathetic and lukewarm towards any constitutional change, no matter how much the political leadership exhorts them to embrace it and talks up one or the other status, whether it be Kingdom Island, Separate Status, Country within a Country, FISSA, or tragically, independence. There is no popular outcry for constitutional change. During the last elections in St. Maarten, Separate Status was never mentioned by any party. Rather, it was sprung upon us, while we quietly were going about our business. Apart from the leader of government, who has a vested interest in Separate Status, and is a very courageous lady, I have never heard any other member of the Executive Council spontaneously express the faintest interest in Separate Status.

It is frequently, if not reliably, said that the Caribbean is the most reported-on area of the world, Irene Hawkings wrote in The Changing Face of the Caribbean. That was in 1970. Within the Caribbean I am certain the Netherlands Antilles occupies a special place as a world record holder in the production of reports. It is within this context that the recently issued report, proclaims with false courage: ‘The time is now, Let’s do it’. Perhaps, its authors suspect only too well what will be its fate. A spot on some library shelf along the 800 or so other reports on constitutional change, gathering dust. The Antilles have cried wolf too often to be credible. On December 13th, 1975, for example, premier Evertsz solemnly declared to the Antillean parliament, that the first phase of the realization of Antillean Independence was about to begin, with the regulation of the internal structure amongst the islands.[iii] This is exactly what the ‘Let’s do it’ report is still trying to report on in 2004, some 30 years later. This is rather odd for as recently as 1993 Payne and Sutton (Modern Caribbean Politics) held that modern politics in the Caribbean has been concerned with the achievement of political independence. A new political party, Movimiento Antias Nobo of Don Martina was founded to guide the process announced by Evertsz. The MAN is now a shambles. After the 1993 referendum, another political party that was supposed to carry out the wishes of the people, the PAR of Miguel Pourier was founded to carry out the restructuring.[iv] It came to nought. In an emotional farewell lecture, entitled ‘The Constitutional Restructuring of the Netherlands Antilles: Not words, but deeds’[v] presented on Friday, June 5th 1995, professor A.B. van Rijn, of the University of the Netherlands Antilles, stated: ‘Disappointment will be disastrous for people’s faith in politics. Not only that, but social peace and the investment climate are at stake’.[vi] Society yawned apathetically at his speech. Life continued pretty much as before. None of his predictions came true. Hirsch Ballin created a stir in 1990 with his ‘Sketch of a Commonwealth Constitution for the Kingdom of The Netherlands’,[vii] which in turn caused more ink to be shed in various publications and articles, most notably by Fernandes Mendes and Bongenaar (Uni ku UNA). The ‘Let’s do it’ report therefore has a long pedigree, going back to the van Poelje reports of 1948. Van Aller writes about a ‘a dizzying number of models’ [viii] with regard to the reports and studies on constitutional reform carried out over the past 50 years. The latest report is but a mish mash of all previous reports with little new to add. Van Aller surveying this state of affairs, writes: ‘(…) one can conclude that restructuring had yielded little. Theory had produced many models, but in politics hardly any attention was paid to them’.[ix] The wandering in the dessert continues.

The reason for this apathy can be traced to several sources, all of them having their roots in our history. No other region has been hit so hard by the double whammy of its history. Not only was the region colonized, but for centuries, the majority black population had to endure the dehumanizing experience of slavery. Both conditions, colonialism and slavery involve the rule over one people by another. Both require learned reflexes to deal with the situation. One such reflex is the loss of confidence. For colonialism to work, the self confidence of the colonized had to be stripped, so that the colonized could place his confidence in the colonizer. Likewise, the slave was stripped of his self confidence, with all confidence subsequently being placed in the master. V.S. Naipaul in his book, The Mimic Men writes about this crippling lack of confidence in post colonial West Indian leaders. Ayearst defines the ‘colonial complex’ as a community-wide inferiority complex stemming from the relative unimportance and subordinate status of the colony as contrasted with the metropolitan country.[x] Singham states:

… those socialized in colonial society exhibit numerous psychological scars. They are therefore often incapable of making the necessary adjustments to achieve the difficult task of decolonization, particularly those tasks involving economic and social change. The colonial personality finds genuine change psychologically upsetting. The elites in colonial societies tend to have basically authoritarian personalities. Authoritarianism is embedded in the entire social structure and the colonial personality structure. Personalities of this type are both aggressive and submissive. In most colonial societies, the middle classes form a large part of the elite. This group has usually sustained particularly severe psychological shocks from colonialism. They at first try to identify with the aggressor, but this provides no permanent psychological satisfaction or security, for they are made continually aware that they are not really accepted by the aggressor, either by open rebuffs or more subtle methods to mark their exclusion and inferiority. The colonized individual fears his aggressor and is never sure how successful his imitation of his superior is. The suspicion lurks that imitation only calls forth ridicule. Colonial societies tend to produce entire elite classes of imitators in the areas of language, dress, social customs, and political forms. The societies of the West Indies still face the difficult task of creating a value system that will free them from the stigma of inferiority and will release the creative energies of their people.[xi]

Dr. Ralph Gonsalves, premier of St. Vincent and the Grenadines writes in this context of learned helplessness. Too many of our Caribbean people, especially leaders have become so accustomed to the idea that they are helpless that they believe it, even when it is patently not true. Indeed, there is a veritable industry devoted to the idea that we are helpless; this industry, based invariably on distorted scholarship, or no scholarship whatsoever, even sets out on a path to make all of us learn to be helpless.[xii] One example of this learned helplessness is the myth of Dutch aid. During a conversation with Ir. Ralph James, a St. Maartener who heads the Department of Development Cooperation in Curaçao, he admitted that the Antilles do not need Dutch aid and that the amount Holland contributes is an insignificant part of the budget. The Antilles and especially St. Maarten have flourished not because, but in spite of Dutch aid. A research paper of the University of the Netherlands Antilles (UNA, 1985) stated in this regard that: ‘Before 1960 all capital investments were financed from local savings (…) Dutch aid has made the Antilles dependent (…) The Netherlands Antilles have up to today not succeeded in carrying out a development policy that results in self sufficiency for the islands and the emancipation of groups in social-economic terms’.[xiii] Following years of close-up studies of the development attempts in one of the world’s most afflicted regions, Gunnar Myrdal came to the conclusion that ‘the participation of outsiders through research, provision of financial aid and other means is a sideshow of rather small importance’.[xiv] It is this hard reality that learned helplessness tends to mask.

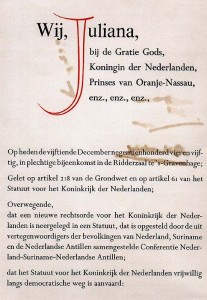

To compound matters for the Netherlands Antilles, the colonizing power, Holland displays a deeply ambivalent attitude towards its colonies. The UNA paper cited states in this regard: ‘So far the Netherlands has not excelled in its role of decolonizer’[xv]. Three major events illustrate this ambivalence: the implementation of the Kingdom Charter, the independence of Suriname and the separate status of Aruba. All of these events were more or less forced on Holland. After World War II, all scholars agree, it was the decolonization pressure from the U.S.A. which forced Holland to eventually implement the Kingdom Charter and grant Indonesia its independence. In the case of Indonesia, the Dutch only gave up after humiliating military defeats and international pressure.[xvi] The Kingdom Charter, with which Holland had hoped to entice Indonesia to remain in the Kingdom, was then hastily sloughed off on the Netherlands Antilles and Suriname. After the riots in Curaçao and Suriname in 1969, during which Holland was forced to intervene militarily in Curaçao and seriously consider the same in Suriname, Holland, its hand again forced by external events, hastily started making plans for the independence of its colonies. In 1972, a Dutch Policy document entitled ‘Turning Point 1972’ (‘Keerpunt 1972’) boldly stated that the Antilles and Suriname would be independent within the next four year governing period.[xvii] Indeed, in 1975 Suriname did become independent. One Dutch writer mockingly called Suriname’s independence ‘Cross-eyed independence; one eye on the airport at Zanderij, the other on the approaching independence’.[xviii] An unintended consequence of this sudden Dutch urge for independence was Aruba’s demand for a separate status. Aruba did not wish to be part of an independent Netherlands Antilles. Here we find another parallel with Anguilla. Anguilla did not want to be part of the Federation of St. Kitts, Nevis and Anguilla because of the old colonial affliction: Anguilla preferred a faraway London to a next-door St. Kitts. The principle was at work in Aruba as well: better a far away The Hague than a close Willemstad. In addition, both realized that seceding from an independent state would be a difficult task.[xix]

During a Kingdom Committee meeting (called to discuss the coming independence) in Paramaribo in 1972, Aruba first expounded its ideas concerning a ‘Status Aparte’.[xx] From 1972 to 1986, Aruba went through an endless cycle of meetings, reports, discussion groups and two round table conferences. However the mass strikes in Aruba in August of 1977 were the real reason why anything finally happened. Events there got so hot that Holland realized that the next step might be armed conflict between Aruba and Curaçao.[xxi] As Vincent Doncker correctly observed, only when blood was about to flow, did change occur. Holland finally consented to hold direct talks with Aruba, according to Article 26 of the Island Regulation of the Netherlands Antilles.[xxii] Until then Holland had resolutely refused to hold direct talks with Aruba about a Status Aparte. Such was not possible Holland insisted, it would violate the integrity of the Netherlands Antilles.

Klinkers commented on this unwillingness of Holland to let go: ‘The very idea of Aruba as an autonomous part of the Kingdom, appeared to be an insane thought. It simply could and would not be done’.[xxiii] When the threat of bloodshed became imminent Holland suddenly dropped its objections. It was possible after all. It still took 9 years, from 1977 to 1986 of endless meetings and talks and reports, but the bridge had been crossed. In 1986 Aruba obtained Separate Status. The decolonization experiences of the Kingdom of the Netherlands show that trying to negotiate constitutional reform with Holland is an exercise in futility. Holland is simply to irresolute to do anything meaningful unless compelled to by force majeure.

The eminent German statesman Bismarck came to a similar German conclusion. After witnessing years of endless meetings and conferences to discuss the union of the various German states into one German nation in the 1800s – some of which were referred to mockingly as professors congresses, because of the large number of academics taking part in the process – he pronounced the words for which he has become famous. ‘By Blood and Iron, unity will be achieved.’ He set about to militarily beat his adversaries into submission and fashion the foundations of the modern German state as we know it today.[xxiv] So the wandering in the wilderness will continue. The inability of Holland to let go, coupled with the ambivalence and apathy of the population of the Netherlands Antilles combine at every step of the way to frustrate any move towards constitutional reform.

A word about Holland’s relationship with Antilles. Like most Antillians, I have never been able to figure out what exactly keeps Holland hanging on. The answer I have been able to distill from several Dutch authors is mostly a colonial hangover that they do not know how to cure. Lammert de Jong in his book The Operations of the Kingdom also puzzled over this question. He described the relationship as steering blind and muddling through.[xxv] There is movement he writes, but as to direction and course one has to guess. Wehry, in his book, Holland and the Caribbean basin, after trying mightily to justify the Dutch presence, finally stated that it is important to Holland because it is the only Member of the European Union, that still has such ties in the Caribbean. Britain had already concluded that colonial possessions in the Caribbean were basically a waste of time and had granted independence to most of its colonies. Only the really tiny islands such as Anguilla, Montserrat, The British Virgin Islands, The Cayman Islands, and Bermuda which refused independence, still remained in the British empire at the time. France had no colonies as such. The overseas departments were an integral part of the French Republic, with full citizenship accorded to the inhabitants.

They were no longer colonials but French citizens. The Dutch presence in Caribbean allowed to share patrol duties with the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard, and this somehow translates into prestige.[xxvi] De Jong writes about the Dutch ego that is flattered because of the Kingdom’s constitutional ties in the Caribbean.[xxvii] Gert Oostindie tellingly describes the relationship as ‘Strangling Kingdom ties’,[xxviii] while Klinkers writes in her thesis ‘The Road to the Kingdom Charter’[xxix] that some members of the Dutch political elite (1950’s) felt that without colonies Holland would sink back to the insignificant status of a country such as Denmark. This situation is all the more perplexing when Great Britain, with more, bigger and richer colonies had come to the conclusion that the colonies were of no use, neither militarily, financially nor culturally. strong>[xxx] De Jong states that contrary to popular belief, the Netherlands Antilles have never in history been a financial cash cow for Holland.[xxxi] Verton, citing Lijphart is of the opinion that Holland’s involvement in the bitter struggles over West New Guinea were not the result of objective interests, but purely and exclusively for emotional reasons.[xxxii] No wonder Klinkers characterized the Dutch approach as ‘Foot dragging decolonization’.[xxxiii] The Antillles until now have never used this Dutch emotional attachment to them to full advantage. It would be interesting for example, to see just how much Holland is prepared to pay for the privilege of indulging its emotions. Klinkers writes about the rigid structure of the Kingdom Charter in this respect.[xxxiv] England on the other hand used the exact opposite approach in the West Indies Act of 1967, by which she entered into a relationship somewhat similar to the Kingdom Charter with her former British West Indian colonies. The West Indies Act was constructed without a clear exit strategy. There is one area in the Kingdom Charter where all parties are treated equally. Art. 55 of the Kingdom Charter grants the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba a veto right over any changes. Holland therefore needs the Antilles if it wishes to get rid of its obligations towards these islands via a change in the Kingdom Charter.

An endless parade of Dutch political parties and Ministers of Antillean and Aruban affairs have issued volume upon volume of studies, reports, aide de memoirs and have held endless round-table meetings and lecture series on the relationship, but until such events as the riots in Curaçao in 1969 or those in Aruba in 1977, Holland does not act. We can therefore safely conclude two things: meetings, lecture-series and round-table conferences will not bring about any constitutional change. The public is apathetic, Holland is clueless and the Antillian political elite too smitten with the colonial complex to bring about meaningful constitutional change.

Any island sincerely desiring constitutional change will have therefore to follow the example of Aruba and Anguilla and engage in creative violence. This is the only means to really get Holland’s attention. In the case of St. Maarten, such creative violence may be largely symbolic and only restricted to some unilateralism. This because unlike Anguilla, Aruba and Curaçao there is no mass movement pushing events. The extreme heterogeneity of St. Maarten society also makes it doubtful whether such a mass movement can be fashioned. The various ethnic groups on the island have divergent interests. Immigrants, though a numerical majority on the island, are first and foremost concerned with economic gain, with little regard for constitutional development or nation building. Given these circumstances unilateralism can take the form of refusing to turn over certain taxes to the Central Government, establishing its own currency, or taking over the police force. These are all goals which might be able to rally a majority of the population to their cause regardless of national origin. Anything short of such drastic action will result in endless round table conferences and another fifty years of wandering in the desert. In closing I would like to leave you with a quote from Michael Manley:

I refer here to the psychology of dependence which is the most insidious, elusive and intractable of the problems which we inherit (…) If a man is denied both responsibility and power long enough he will lose the ability to respond to the challenge of the first and to grasp the opportunity of the second (…) So too with societies. Denied responsibility and power long enough, they show a similar tendency and can become almost incapable of response to opportunity because there is not the habit of self-reliance.[xxxv]

NOTES

i. The main text of this paper is in English. Quotes and references to Dutch sources are translated. The original Dutch quote or reference is footnoted.

ii. Payne, Anthony & Paul Sutton, Modern Caribbean Politics. Kingston, Jamaica: Ian Randle Publishers, 1993. See in this context also the discussion by Edward Laing in: Independence and Islands. The Decolonization of the British Caribbean, pp. 305-312, in a paper read at an executive session of the International Law Section of the American Bar Association, held in Puerto Rico in December 1978.

iii. Aller, H.B. van, Van Kolonie tot Koninkrijksdeel: de staatkundige geschiedenis van de Nederlandse Antillen en Aruba (van 1634 tot 1994), p. 353. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff, 1994.

iv. PAR stands for Partido Antia Restruktura (Antillean Restructuring Party).

v. De Staatkundige herstructurering van de Nederlandse Antillen: Geen woorden maar daden!.

vi. Een teleurstelling van de verwachtingen zou desastreus zijn voor het vertrouwen in de politiek. Maar dat niet alleen: ook de sociale vrede en het ondernemingsklimaat staan op het spel.

vii. Schets van een Gemenebest Constitutie voor het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden.

viii. ‘een duizeling wekkend aantal modellen’.

ix. Aller, H.B. van, op. cit.: ‘Dit alles overziende kan worden vastgesteld dat de herstructurering weinig had opgeleverd. De theorie had vele modellen aangedragen maar hieraan werd politiek gezien nauwelijks aandacht aan besteed’.

x. Ayearst, M., The British West Indies. The Search for Self-Government, p. 61. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1960.

xi. Singham, A., The Hero and the Crowd in a Colonial Polity. New Haven: Yale University Press 1968, pp. 9-11.

xii. See Dr. Gonsalves contribution in: Governance in the Age of Globalisation, Caribbean Perspectives, Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers, 2002, p.6, in which he attributes the phrase ‘learned helplessness’ to Charles Leadbetter’s book: Up The Down Escalator. Why the Global Pessimists are Wrong.

xiii. Voor 1960 werden praktisch alle kapitaalsuitgaven uit lokale besparingen gefinancierd (…) De Nederlandse hulp heeft de Antillen afhankelijk gemaakt (…) De Nederlandse Antillen zijn er tot op heden niet in geslaagd een ontwikkelingsbeleid te voeren dat resulteerde in verzelfstandiging van de eilanden en emancipatie van groepen in sociaal-economische zin’. Koulen, Verton en Silberie, Dilemma’s van dekolonisatie en ontwikkeling: ontwerpen voor onderzoek, UNACahier No. 9, mei 1985, p. 75.

xiv. Tibor, M., From Aid to Recolonization: Lessons of a Failure. Harrap: London, 1973, p. 154.

xv. Nederland heeft als dekolonisator tot op heden geen glansrol vervuld. UNA-Cahier, op. cit., p.5.

xvi. See for a more thorough discussion, Albertini, Rudolf von, Decolonization. The Administration and Future of the Colonies 1919-1960. New York: Doubleday & Co, 1971, pp. 492-499.

xvii. Ketelaars, H., (editor), Het ontstaan van Suriname als nationale staat: een uitwerking volgens CSE model. Leiden: Coordinaat Minderhedenstudies, RUL, 1990, pp. 121-123.

xviii. ‘De schele onafhankelijkheid; één oog op Zanderij, het andere op de komende onafhankelijkheid ’ Willemse, Glenn (ed.), Suriname. De schele onafhankelijkheid. Amsterdam: Arbeiderspers, 1983.

xix. See for a discussion of the Anguilla separatist movement, Brisk, W.J., The Dilemma of a Ministate: Anguilla. Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1969.

xx. Voorbraak, D., De Nederlandse Antillen. Een onzekere toekomst, p. 24. Master’s thesis. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, 1986.

xxi. Aller, H.B. van, op. cit.

xxii. De Eilandenregeling van de Nederlandse Antillen’.

xxiii. Vanuit Nederlands perspectief was afscheiding van het eiland Aruba vrijwel volledig ondenkbaar; eerder werd al de opmerking aangehaald dat “het rijksdeel Aruba” zo’n krankzinnige gedachte is’. Klinkers, Inge A.J., De weg naar het Statuut. Het Nederlandse dekolonisatiebeleid in de Caraïben (1940-1954) in vergelijkend perspectief, p. 434. Doctoral thesis, Utrecht University, Annex 5, [s.n.]: Utrecht, 1999.

xxiv. See for an excellent discussion of Bismarck’s rise to power, Lokin, J.H.A. & Zwalve W.J., Hoofdstukken uit de Europese Codificatie Geschiedenis, pp. 222-230. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff/Egbert Forsten, 1992.

xxv. Jong, L. de, De Werkvloer van het Koninkrijk. Over de samenwerking van Nederland met de Nederlandse Antillen en Aruba, pp. 14-15. Amsterdam: Rozenberg Publishers, 2002,

xxvi. Wehry, G.A.M., Nederland en het Caraïbische bekken: de Nederlandse Antillen, Aruba en het buitenlands beleid. ’s-Gravenhage: Nederlands Instituut voor Internationale Betrekkingen ‘Clingendael’, 1988.

xxvii. Jong, L. de, op. cit., pp. 208-209.

xxviii. Oostindie, Gert & Inge Klinkers, Knellende Koninkrijksbanden. Het Nederlands dekolonisatiebeleid in de Caraïben 1940-2000. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2001.

xxix. Klinkers, Inge A.J., De weg naar Het Statuut. Het Nederlandse dekolonisatiebeleid in de Caraiben (1940-1954) in vergelijkend perspectief, Doctoral Thesis Utrecht State University, Utrecht, 1999.

xxx. Compare: Payne, A., The International Crisis in the Caribbean, p. 92. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984.

xxxi. De Jong, op. cit., p. 208.

xxxii. See Verton’s contribution in: Sedoc-Dalhberg, Betty (ed.), The Dutch Caribbean: Prospects for Democracy. New York: Gordon and Breach, 1990, p. 204.

xxxiii. ‘Schoorvoetende dekolonisatie’.

xxxiv. Klinkers, Inge, op. cit., Chapter 10, ‘Naar een balans’.

xxxv. Manley, M., The Politics of Change. A Jamaican Testament. London: Andre Deutsch Ltd., 1974, p. 21

Bibliography

Albertini, Rudolf von, Decolonization. The Administration and Future of the Colonies 1919-1960. New York: Doubleday & Co, 1971.

Aller, H.B. van, Van Kolonie tot Koninkrijksdeel. De staatkundige geschiedenis van de Nederlandse Antillen en Aruba (van 1634 tot 1994). Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff, 1994.

Ayearst, M., The British West Indies. The Search for Self-Government. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1960

Jong, Lammert de, De werkvloer van het Koninkrijk. Over de samenwerking van Nederland met de Nederlandse Antillen en Aruba. Amsterdam: Rozenberg Publishers, 2002.

Ketelaars, H. (ed.), Het ontstaan van Suriname als nationale staat: een uitwerking volgens CSE model. Leiden: Coördinaat Minderhedenstudies, RUL, 1990.

Klinkers, Inge A.J., De weg naar Het Statuut. Het Nederlandse dekolonisatiebeleid in de Caraïben (1940-1954) in vergelijkend perspectief. Doctoral thesis, Utrecht University, 1999.

Koulen, Verton & Silberie, Dilemma’s van dekolonisatie en ontwikkeling: ontwerpen voor onderzoek. UNA-Cahier No. 9, mei 1985.

Laing, Edward, Independence and Islands: The Decolonization of the British Caribbean, pp. 305-312. Paper read at an executive session of the International Law Section of the American Bar Association, held in Puerto Rico in December, 1978.

Mende,T., From Aid to Recolonization. Lessons of a Failure. London: Harrap, 1973.

Naipaul, V.S., The Mimic Men. London: Picador, 2002 (first published 1967).

Oostindie, Gert, & Inge Klinkers, Knellende Koninkrijksbanden. Het Nederlands dekolonisatiebeleid in de Caraïben, 1940-2000. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2001.

Payne, Anthony, The International crisis in the Caribbean. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984.

Payne, Anthony & Paul Sutton, Modern Caribbean Politics. Kingston, Jamaica: Ian Randle Publishers, 1993.

Rijn, A.B. van, De Staatkundige herstructurering van de Nederlandse Antillen: Geen woorden maar daden! Willemstad: Afscheidsrede, Universiteit van de Nederlandse Antillen, 1995.

Sedoc-Dalhberg, Betty (ed.), The Dutch Caribbean: Prospects for Democracy. Gordon and Breach, 1990.

Voorbraak, D., De Nederlandse Antillen. Een onzekere toekomst. Master’s thesis. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, 1986.

Wehry, G.A.M., Nederland en het Caraïbische bekken: de Nederlandse Antillen, Aruba en buitenlands beleid. ‘s-Gravenhage: Nederlands Instituut voor Internationale Betrekkingen Clingendael, 1988.

Willemse, Glenn (ed.), Suriname. De schele onafhankelijkheid. Amsterdam: Arbeiderspers, 1983.