The Non-German German

The Tel Aviv Review of Books (Spring 2020) – An Israeli in Berlin asks: Does German culture belong to me?

The Tel Aviv Review of Books (Spring 2020) – An Israeli in Berlin asks: Does German culture belong to me?

In recent years, I have been diving deeper and deeper into the treasures of German culture. I read and write, thinking about questions of identity and belonging against the backdrop of Israeli and Jewish immigration to Germany, which, in literary terms, dates back to philosopher Moses Mendelssohn’s arrival in Berlin in 1743. Is German identity the exclusive property of German passport holders? Or is it plentiful enough to be shared with aficionados and non-citizen residents? In other words, is “Germanness” more than a question of nationality? Having spent the last six years in Berlin, as an immigrant encountering the local and other immigrant cultures, I have come to realize that the answer to this question is more multilayered than I thought.

Having read W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, I watched documentary films about the author, a German émigré in England. For him, the barren terrain of East Anglia was a springboard for far-flung journeys through Europe’s colonial history, through antiquity, philology, and many other realms. Does any of that make him an English writer?

Sebald, like a host of other German intellectuals, protested against the memorialization of the Holocaust in his native country. His physical rupture from his homeland (like that of novelist Thomas Mann before him, who settled in Switzerland in the wake of the Second World War) was tantamount to a cultural rebellion. It opened a space for a critical engagement with processes that ordinary Germans, shielded by the boundaries of their nation, could not and cannot fully grasp.

I read famed Israeli poet Leah Goldberg’s novel Losses, an out-and-out homage to her former home of Berlin. Like the author, the protagonist is a Jewish poet and scholar turned Zionist, who arrives in Berlin on the eve of the Nazis’ ascent to power, and is forced to return to Palestine, where he had spent a year on kibbutz, against his will. Despite the novel’s bitter end, one can feel her overflowing love for the cosmopolitan capital in the final moments before its descent into the darkness of fascism. Goldberg’s love for Germany is expressed, too, in her debut poetry collection Smoke Rings (1935). As a newcomer to Germany, I have only recently come to know the splendor of the Harz Mountains, where Goldberg set one of the book’s poems; it was the setting, too, for Goethe’s famous ascent to the summit of Brocken:

Like a light-yellow cloud down the slope

my great sorrow, escaped from captivity, flutters.

A splendid laugh enchants my heart, strange though it is

that the man walking beside me is not beloved.

These are rare moments of exaltation sparked by her visit to Wernigerode, a town on the slopes of the mountains. This journey was a formative experience, writes Dr. Giddon Ticotsky in the afterword to Losses. “She was welcomed with open arms into a Christian German family, and tried her luck—for the first and last time—to write in German… an attempt which won praise from the head of the family.”

Goldberg’s nostalgia for Berlin reminds me of Zeev Vladimir Jabotinsky’s reminiscences, in his beautiful novel The Five, of Odessa on the eve of the First World War:

“Looking back at all this some thirty years later, I think that the most curious thing about it was the good-natured fraternization of nationalities. All eight or ten tribes of old Odessa met in that club, and it fact it never occurred to anyone, even in silence, to note who was who. All this changed a few years later, but at the dawn of the last century we genuinely got along. It was strange; in our homes, it seems, we lived apart; the Poles visited and invited other Poles, Russians invited Russians, Jews, other Jews; exceptions were encountered relatively infrequently; but we had yet to wonder why this was so, unconsciously considering it simply an indication of a temporary oversight, and the Babylonian diversity of our common forum, as a symbol of a splendid tomorrow.”

Of all people, these were the words of the stern man who wanted to erect an “iron wall” in the Middle East. While fighting for the Zionist cause in Palestine in the 1930s, he possessed the singular ability at once to both wallow in somber nostalgia and desperately cling to that cosmopolitan, diasporic moment that Zionism has since sought to efface.

Amir Eshel’s wonderful new Hebrew and German poetry book Sketches wanders among contemporary artist Gerhard Richter’s 40 graphite-on-paper drawings from 2015, a project reminiscent of his 2014 tribute to the Birkenau concentration camp. Richter’s works dissolve into poems, sketches waltzing lugubriously to an old violin—while I read and read, insatiably, saving some for the next day. Here, too, the dance is post-apocalyptic:

An aimless raven

In the soft afternoon light

on the pavement tiles

opposite the Cologne Cathedral

prancing between empty plastic bags

bottles

and apple cores.

And at once turns its gaze

to the towers

spreading its wings

rising

to the stained-glass windows

hovering above the rooftops

its body briefly blocking

the sunlight

And in this fleeting darkness

For one brief moment

Things fall into place.

The sounds of visions

shatter

to the place

Bits and pieces

between night and day

day and night

What will we see between the shadows

what will we know

the range of the question

is the range of knowing

Dust

dust

dust.

Here, the wandering raven is a symbol of rupture, just as essayist and poet Shva Salhoov wrote of the work of artist Aharon Message: “The raven represents an ironic character in the post-flood renewal story. The raven was Noah’s first messenger, sent to see whether the water had dried and land had appeared. The raven never returned: ‘At the end of forty days Noah opened the window of the ark that he had made and sent out the raven; it went to and fro until the waters had dried up from the earth.’ The raven abandoned its mission.”

Eshel’s poem is suddenly interrupted by a reference to Cologne’s imposing Gothic cathedral. Landmarks are often foreign to poetry. A landmark, complemented by a purgation of the mind. Why Cologne? The last time I was there, the cathedral seemed so daunting. Eshel explains: “This book is the result of an ongoing conversation, beginning in the questions that Gerhard Richter’s works have evoked in me over the past thirty years. The conversation continued during a meeting held at Richter’s atelier, near Cologne, in the spring of 2016, and was followed by the poems that I wrote, in German and in Hebrew, some of which are included in this volume.”

The reckoning in this poem relates to the encounter between the Israeli scholar, who teaches at an American university, and the German artist in his Cologne atelier. Is this book, comprising poems in Hebrew and German, a German cultural product? Is it an Israeli cultural product, even though Eshel does not live in Israel and writes occasionally in German? Can these two cultures even converse, in either a Middle Eastern or a European context?

Who owns German culture in this day and age? Can a Jewish or Israeli poet, writing in broken Hebrew, broken English, and broken German and living in a German-speaking region be considered a German, or a European, poet? Can Leah Goldberg’s and Amir Eshel’s works be incorporated into the local (German) curriculum as native works? In the introduction to their bilingual poetry anthology Zukunftarchäologie (‘The Archaeology of the Future’), Giddon Ticotsky and Lina Barouch write: “It is no coincidence that every poem appears in both Hebrew and German. One way or another, it seems that these poets return to their German-speaking home thanks to the work of the translator; suddenly, it feels like Leah Goldberg’s lines were meant to be written in German in the first place.”

Goldberg, for her part, expressed her ambivalent views on Europe in a newspaper column written in 1945, years after Losses had been completed: “We shall never forget, you; the wounds of love and the wounds of hate shall never be forgotten. Until our dying day we shall carry it in us, this enormous pain called Europe – ‘your Europe,’ ‘their Europe,’ but not ‘our Europe’ – even though we were hers, very much so.”

Meanwhile, today, an Israeli and Jewish presence is taking shape in German culture. Jan Kühne, a poet, translator, and scholar, includes in his first book of poetry an entire chapter dedicated to the crossover between German and Hebrew writing. Unlike Eshel, he does not give the reader the benefit of presenting the two languages separately, but instead mixes and mashes them together. His writing is an elaborate graphic double entendre, where, for example, the Hebrew letter samech (ס) can sometimes be construed as the German ö. Such is the case in the poem “Ivrit”, which I had the privilege to hear in a live reading at the Yafo restaurant in Berlin’s Mitte district:

Du redest Ivrit

לא ידעתי אז למה,

reden wir nicht gleich

עברית במקום שאני

Mühe mich ab mit dem

גרמנית וכל שבירותיה

Der Zunge?!

Also wirklich

היית יכול להגיד לי יותר

Früher und dann wäre alles

קצת יותר פשוט

Gewesen. Aber ist ja

עכשיו לא משנה. אנחנו

Verstehen uns auch

This short sample exemplifies the poem’s playful use of Hebrew and German. I am struck by this charming playfulness. When I attended the reading, my brain worked hard to translate the German, and place it alongside the familiar Hebrew. But the average Israeli reader has no knowledge of German, except perhaps via vestiges of parents’ or grandparents’ German or Yiddish. Kühne, in effect, takes the reader’s knowledge of Hebrew almost for granted. He seems to be asking: Why did you let me wallow in that terribly complex German? And at the same time Kühne, as a German, imagines himself as momentarily external to the German language, like the (Hebrew) immigrant who suddenly discovers new organs growing in him. And these organs do not always conform to the strict rules of German grammar.

The Hebrew University-based Kühne speaks fluent Hebrew. In addition to his academic publications and poetry, he regularly publishes in the literary supplement of the Hebrew Haaretz newspaper. Perhaps we should not be so surprised: after all, Hebrew culture has already absorbed into its midst Palestinian writers who opted for Hebrew, or Jewish Iraqi writers who abandoned their mother tongue. So should Kühne, who juggles effortlessly between German and Hebrew, be considered a Hebrew poet? This question mirrors the one that opens this essay: To whom does this culture belong?

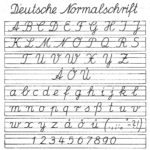

German culture belongs to whoever wants or sees themselves as belonging to it. Nevertheless, there is a dialectic element as well as an anti-national one. Historically, German culture has been predicated on two types of boundaries, linguistic and geographic: correct German, on the one hand, and the German-speaking space, on the other. Recently, the Literary Colloquium Berlin (LCB), one of the German capital’s premier cultural institutions, held a conference for Berlin-based non-German writers, and launched a project intended to map the venues where different ethnic groups read poetry. In so doing, the LCB has, in effect, shifted its focus to capturing Berlin’s non-German culture. Many Germans do not see these writers as full members of the nation, because of their language, their ethnicity, and perhaps their religion. But culture might provide a means for inclusion via the back door, in the wake of the growing realization that nationality and citizenship are not remotely synonymous with culture. The same happens in Israel, with asylum seekers, migrant workers, Palestinians, and others, who de facto enrich the local culture. They belong to Israeli culture even when Israel fails to recognize that belonging.

Life in Germany has taught me to abandon the Zionist perspective through which I had been instructed to evaluate writers such as Goldberg, Jabotinsky and others. Thanks to them, I learned a lot about the local culture and to a certain extent became a local fixture – both as an artist and as a resident. Ironically, in this northern European climate, as trees were shedding their leaves to form a beautiful golden carpet, I was fortunate to discover exiled Middle Eastern writers. In late 2018, I organized a special event, where Jewish and Arab writers from Arab countries met to engage in artistic dialogue. Israeli novelists Hila Amit Abbas, Zehava Kalfa, Gidi Farhi, and I shared a platform with Egypt’s Mariam Rashid, Kurdistan’s Musa Abdulkadir and Maban Younes, and Syria’s Hassan Al Fadel. More than 130 people attended the event at the LCB, opposite the notorious Wannsee castle where the Final Solution was conceived. In the event, entitled “Jews and Arabs reconnect with the Middle East”, we sought to explore the unique cultural links between Jewishness and Arabness, which were severed when we migrated to Israel and became sealed off from the rest of the Middle East. Another layer of irony is that this cultural space, the one that I feel I most belong to, is itself foreign to its setting. These encounters, which occur daily in immigrant neighborhoods, could easily have remained shallow, but in organizing these events we decided to go deeper and explore the roots of these connections.

For an Israeli entering a trilingual space (Hebrew, English, German), culture is no longer bounded by national borders. It’s open to the four winds, like Abraham’s tent. On the one hand, through the Hebrew language I am in dialogue with Israeli culture (even though the Hebrew-speaking diaspora is not recognized as part of it). On the other, I am in a renewed dialogue with Europe: not through the usual Eurocentric, critical, or post-colonial lenses, but as a newcomer negotiating his terms of belonging.

—

Previously published in: The Tel Aviv Review of Books (Spring 2020) – https://www.tarb.co.il/the-non-german-german/