When Congo Wants To Go To School – Educational Organisation In The Belgian Congo (1908-1958)

No Comments yetContexts

The first part of this study will concentrate on the wider environment within which daily practice of colonial education is situated. It progresses in three stages in accordance with the aim of the research. Three chapters correspond with these three stages. The general, macro-institutional context of the phenomenon of colonial education is considered in the first chapter. This includes a discussion of the organisational development and politico-strategic factors that influenced this phenomenon. The development of the educational structures is indicated from the angle of the interaction between state intervention and the Catholic initiative. Within that framework the major themes in the content and emphasis of colonial lesson plans are also considered, as are the opinions on these subjects. Finally, figures are given to allow an estimate of the quantitative development of education in the colony. The second chapter shifts the focus to Belgium. The preparation, training, ideas and worldview with which the missionaries left for the Belgian Congo will be considered more closely. This chapter is divided into two parts. The first part considers a number of broad social and historical factors that played a part in the formation of the missionaries’ general intellectual baggage. Mainly results of existing research are presented and discussed in this part. The second part takes a closer look at the people who are of specific interest to us, covering the preparation and training given to the Sacred Heart Missionaries in Belgium and using specific source material. In the third chapter we make the journey to the Congo together with these missionaries. A number of elements are given in a short outline that also constitute the direct context of their work. Firstly, a description is given of the creation and growth of the mission region in which they were active. Then follows the introduction of the other missionary congregations, with which the Sacred Heart Missionaries cooperated. Finally, quantitative data are brought together with regard to the development of education, both for the mission region as a whole and for the various mission posts separately.

Educational organisation in the Belgian Congo (1908-1958)[1]

Before attempting to create an image of the educational development in the vicariate of the MSC on the basis of figures and other concrete data it is perhaps useful to consider the official educational organisation in the Belgian Congo.[2] The term ‘official’ should be taken with great circumspection in this. After all, the interaction between the state, which would logically be associated with the term “official” and the (catholic) missions, proved a constitutive element in the development of the colonial educational system. As a result an attempt has been made in this chapter to give an overview of Belgian colonial education from an organisational and politico-strategic angle, in which the relationship between the government and the missionaries is considered. The most extensive study of the development of the school curricula and school populations can be found in Pierre Kita’s Colonisation et enseignement.3] Although his study is clearly much more extensive, gives a general overview and also emphasises the initial impulses of the development of education in the early years of Belgian colonisation, this chapter approaches from a different angle, namely the increase in state intervention in education and the development of the school network. In this way an attempt will be made using contextual (and statistical) data on the development of primary education to sketch a representative framework for the regional trends which are then described.[4]

Traditionally it is assumed that the colonisation of the Belgian Congo was the result of a convergence of three players: church, business and state. Each had its own interests and relied on the two others to support it. In order to understand the educational organisation properly it is only necessary to focus on two of these three players. The relationship between the state and the missionaries was certainly not unambiguous. The missionaries were divided into two large groups, the Catholics, by far the majority in the Congo and the Protestants, traditionally well represented in Africa. This is unlike the situation in Belgium where the catholic church had developed to become the official state religion since independence and completely controlled education. The colonial administration was the requesting party for the collaboration with the missionaries, which does not mean that the relationship with those missionaries was always free from criticism or unchanging. In time different currents, preferences and political opinions started to become clear in relation to the colonial educational issue. For practical reasons the remainder of this thesis almost exclusively considers Catholic missionary education. Both non-denominational and protestant education disappear from sight in the following which does not however mean that there was no education other than Catholic education, let alone that it was of no importance.

1. First period: starting up education

1.1. The principle: the State proposes, the mission disposes

The earliest form of colonial education was based on an agreement between the king and the Propaganda Fide[5] in Rome and with certain congregations of missionaries. The political organisation of the colony was minimal in the initial period and it was centralised in Brussels. The king established his own colonial government that was responsible for the accounting for his company and contacts with the Congo. From 1885 a department of Affaires étrangères, Justice et Cultes was established. This does indicate that the missions immediately occupied an important place in colonial politics. The new administration of the Congo Independent State only had three departments (the other two were the Ministry of Home Affairs and Finance).[6] With regard to education a distinction was made between official schools founded by the state, for which missionaries were relied on and independent education, that was based on the personal initiative of the missionaries and the financial support of which was given by the government. The official schools were the original school colonies, institutions under a quasi-military regime, where children were given practical training under the guardianship of the government. These were also run completely by missionaries.[7] The first step was placed organisationally in 1906 when the predominantly informal agreements between the king and church resulted in the first official text: “On 26 May 1906, the Holy See and the Independent State signed a Treaty according to the terms of which the Catholic missions, almost completely Belgian, were granted the land required for their work, under a set of conditions, notably the obligation of ensuring general, professional and agricultural education.”[8] It is hard to assess the concrete importance of this Treaty, but according to Pierre Kita it should certainly not be considered the beginning of systematic state intervention. On the contrary, he claims, education was left completely to the initiative and means of the missionaries nor was the quantitative development of the schools stimulated by it. The importance of this treaty is consequently also much more at a political level because it indicated the direction in which education policy would further develop.[9]

On 15 November 1908 the Congo was officially declared a colony of the Belgian state. The administration of the state of Congo now fell under its own ministry, under the direction of a minister who, like the other Belgian ministers, was governed by the Belgian Constitution. After this transition the authority for education and missions remained in the same package, namely in the first general directorate of colonial management. After the First World War the administration was decentralised to the colony. This was accompanied by a reorganisation of the central services in Brussels, in which ‘worship’ and ‘education’ formed a separate directorate. The Charte Coloniale, to be considered the Founding law of the Belgian Congo, included the principle of freedom of education from the Belgian Constitution and the authority over education was placed completely on the governor-general: “He protects and promotes without distinction between nationality or religion, all religious, scientific or charitable institutions and enterprises formed and set-up for this or intended to educate the natives and to allow them to understand and value the advantages of civilisation.”[10]

The concrete provision of education was left de facto to the people in the colony. It may be concluded from this that the Belgian government preferred to continue the informal method of Leopold II and to rely completely on the missionaries for the development of a network of schools, that was considered necessary to make it possible to deploy the population in the economic development of the colony. A general assessment for this first period is that education, and more specifically missionary activity, was considered important in the strategy for conquering the colony and the occupation of the territory. The statement from 1916 by the Minister for the Colonies Renkin in a letter to the governor-general is telling in this regard:[11] “If we could manage to replace the white staff by committed and skilled blacks, the progress would be incredible from a financial, political and economic point of view.”[12] Education may have been presented as a means to bettering oneself, in reality very utilitarian intentions were also involved. However, this double standard was not expressed explicitly. As such, education was not placed on the foreground. It was not made into an issue. It appeared as though education and politics formed a singled discourse. They thought they were both important, needed each other and reinforced each other. Nevertheless at some points major negotiating took place between certain congregations and the government. For example Jules Marchal extensively considered the conflicts relating to financial and organisational problems.[13] And within the administration itself a number of assumptions, prejudices and preferences were maintained, including in relation to the quality of education from certain congregations.[14] The cooperation between Church and State was not however questioned in itself, even though it functioned in a very implicit way, as there was no real legal basis for it. People supported each other: the Catholic missions did not desert Leopold II during the campaigns that arose against his regime and the government relied on the missions, if not from conviction, then at least on economic grounds. The rights of the strongest consequently played an important part in this.[15] The government prospered, the church could use this to the full and the government profited from that in its turn.

1.2. Beginning of government involvement

1.2.1. The Franck Commission

The ‘laissez faire’ attitude that characterised the government’s attitude to a great extent was really broken for the first time after the First World War by the liberal Louis Franck.[16] After the initially dismissive attitude of the Belgian government to take over the colony, this was the first time that a person at a government level saw a need also to invest in “the Congo” instead of simply extracting money from it. An economic and social development plan was also developed for the colony under his impetus. Education was also a part of that. Franck brought a commission of experts together to give shape to the colonial educational structure. On 10 July 1922 the “Franck Commission” as it would later be called, was formed. It comprised leading civil servants, people from the educational sector and delegates from various missionary congregations. As shall be shown below, the influence of the Catholics was very great in this commission. More generally, the question may arise as to what encouraged a liberal politician to support and develop catholic education. Numerous reasons have been given for this. Firstly there were grounds of a general political nature. In this way the liberal party was more than prepared in this period to compromise in relation to enduring government participation.[17] In addition there were personal political motives: Franck wanted to secure his own ministerial seat and had to stay on good terms with the Catholics. In the early twenties there had been a serious incident between the governor-general appointed by Franck, Maurice Lippens,[18] whose ideas, e.g. relating to indirect management, conflicted severely with the forces of conservatism among the missionaries.[19] Franck’s consideration and the influence of the missionaries may also be partly explained by that.[20] However, these political motives are not enough. One of Franck’s most quoted statements relating to colonial education was that “When concerned with the moral education of the natives, it is important to ensure that we do not transfer our European conceptions to Africa. (…) If Europe has perhaps passed the age of religions, Africa is certainly in the age of religions. No factor exists that may act with more energy and more power on the moral education of the natives than the religious action. (…) Consequently, we shall protect the evangelisation in Africa, without moreover establishing a distinction between the Christian religions.“[21] Whether this truly related to a personal conviction or the simple far-reaching influence of the administration on the Minister will probably never be completely clear. A combination of both seems most likely. The fact is that it was already generally assumed at the time that this influence existed: the conventions that arose from the activities of the commission were called the “De Jonghe Conventions”, referring to the director-general at the ministry for the Colonies. Finally, there were certainly also financial considerations in the proceedings. The cooperation with the missions was considered much cheaper than setting-up a complete own educational network.[22]

1.2.2. Edouard De Jonghe and his influence

If one person can be indicated as the defining influence on the development of “colonial education”, both in the colony and in Belgium, it is Edouard De Jonghe.[23] De Jonghe was very industrious concerning the colonial curriculum from the end of the First World War. He published a few articles relating to the issue of the further orientation of the education even before the Franck Commission. Already in April 1922 he published an article in the periodical Congo, entitled L’instruction publique au Congo belge.[24] This article was probably inspired by the criticism that had been given by Lippens with regard to colonial education. De Jonghe even stated in the introduction that criticism could be heard from all sides because the government had done nothing for education and that there was no curriculum in the Congo. He also took responsibility for ensuring more publicity for what he described as “l’importance et la diversité de leurs oeuvres d’enseignement“, which was clearly referring to the missions. In the same article he gave a summary of the educational initiatives then existent in the Congo. He assumed the principle of a dichotomy between schools with a utilitarian aim and schools that attempted to perfect the Congolese. He did not want to use the then apparently already common division into ‘official’, ‘subsidised’ and ‘independent’ schools (écoles officielles, subsidiées ou libres). In his opinion this division did not have any official or legal basis but was a pure question of facts. Moreover the terms used were apparently also too unclear to base representative statistics on them. However, later in his article another, more strategic reason emerged. Citing the objectives of the Colonial University, De Jonghe assumed that a successful colonisation was only possible if the colonised people got equal or more advantages from it than the colonists. This then allowed him to indicate that the schools that did not have a directly utilitarian use for the coloniser were in fact almost all run by missionaries.[25]

De Jonghe would later also publish extensively on educational issues. A number of those publications shall be considered later in this study. It is clear that a number of De Jonghe’s ideas, put forward in these articles, were finally also included in the school regulations. This is clear for example in relation to the use of language. Another element that must have contributed and that is not mentioned as such in any of the literature consulted, is the study trip De Jonghe made in the Congo, from July 1924 to January 1925. The trip took place at a time when the provisional projet d’organisation already existed. De Jonghe announced his trip to the rector of Leuven University, Mgr. Ladeuze in a letter from June 1924: “I will end by informing you that Mr Carton would like to entrust me with the task of inspecting the education in the Congo with a view to the organisation of this and the remuneration of the national missions working in education in the Congo.”[26] The fact that this trip was announced barely a month before De Jonghe’s departure, while De Jonghe and Ladeuze were in regular contact with each other, indicates that there was some urgency in the matter. However, it is not clear what the exact reasons or causes were for this.

De Jonghe kept a relatively detailed account of the entire trip.[27] It contains a wealth of information on a very extensive number of schools that he visited throughout the country. Occasionally, he also mentioned something about his meetings with specific people, usually missionaries. The report clearly shows that De Jonghe did not hesitate to defend the missionaries and that he did not try to hide his own Catholic inspiration. At one point the account mentions a considerable increase in secular rural schools in the East province, financed by the receipts of the native courts. De Jonghe reacted categorically by stating that the territorial administration was not qualified to supervise the teachers in this type of school and that the education and training of the Africans presupposed the Christian faith, an element that was missing from the secular schools. He also added that the creation of such schools would necessarily result in conflicts with the missionaries.

The general considerations at the end of the account make it possible to deduce that this did relate to a type of inspection visit and that De Jonghe had been given the task of testing what people in the field thought of the project text and how it could be implemented. He described his objectives as follows: “My objective was to collect general documentation on the schools in the Congo by visiting the schools established on my route, consulting the archives of the General Government and the provincial Governments, conferring with the religious authorities in order to see whether the adoption project for the schools of the national missions is feasible.”[28] It is striking that De Jonghe mentions projet d’adoption [adoption project] here, something that was not done in the public discourse relating to the project. It is consequently not surprising that the first conclusion of De Jonghe related to the enthusiasm of the missionaries concerning the financial side of things (the substantial increase and systemisation of the subsidies). Nor would he be stopped by less enthusiastic reactions. A number of smaller congregations expressed objections against the project because their material situation could not fulfil certain subsidy conditions. De Jonghe proposed to offer them a transitional period, so that they could get themselves in order and to give them a higher subsidy in the meantime. Furthermore he emphasised the need further to develop girls’ education and consequently schools in the hands of female religious. A different bell was sounded in relation to the training of Congolese teachers. The missionaries felt that the demands set were too high in relation to their level of education and that they could not be expected to fulfil higher demands than Belgian teachers. In this De Jonghe wrote, “Experience has shown that the black is not able to produce continuous effort. Left to himself, he will easily return to practices condemned by civilisation.”[29] Partly as a result of this he believed it was better to have the schools run by missionaries instead of by lay people. Furthermore the missionaries mainly insisted on a regulation that could be adapted very easily to local needs. For instance, the language used when teaching and the time schedules should be adapted in relation to the local situation. (Read: it was not desirable to teach French everywhere and the subsidies should certainly not be made dependent on teaching French). Finally it was also greatly desirable to provide more subsidies for so-called ‘urban’ schools (écoles urbaines) than for rural schools, because they had to comply with higher requirements and because they had to pay their teachers more because of competition with other employers.[30] That account would effectively be taken of these and other remarks, is finally apparent from the last sentence in the account: “Some other remarks, suggested by the missionaries, have been recorded in the form of amendments to the project (attached) for the organisation of independent schools with the assistance of the national missions.”[31]

1.2.3. Antecedents

However, starting the history of the official school programmes with the activities of the Commission or Louis Franck’s commission would not be exact. Although it is true that there is only a question of real organisation in the field from that moment, regulations on the matter had been discussed much earlier. In his work, Pierre Kita mentioned various initiatives, conversations and research that were launched from various directions during the period before the First World War. He also refers to the educational survey that was carried out during the war, originating from the ministry for the Colonies. It was aimed at company directors, government agents and missionaries. Fabian also refers to this survey in Language and Colonial Power. Based on what both authors say it may be concluded that the survey was rather indicative of the way in which colonial education was conceived in the metropole. The questions were apparently rather directional and a great preference was indicated for utilitarian education to the service of the colonisers.[32] Pierre Kita claims that the results of this survey were certainly an instrument of the Franck Commission. However I could not find any solid evidence of this. According to the information given by Fabian, the results of the survey were moreover much too disparate to allow any general conclusions to be drawn. Perhaps it did exercise some indirect influence via the proposals of the colonial administration in London.

In any event this ‘London project’ appears to be the most important of the proposals from the 1908-1918 period. During their exile in London the members of the ministry for the Colonies maintained negotiations with the mission superiors, that concluded in a proposal for a curriculum which would be applied throughout the colony. Primary education of twice two years was central in this, possibly as a preparation for a number of ‘special schools’ (clerical school, teacher training or technical school) and a very strong emphasis was placed on manual labour: “Two hours shall be spent per day on manual labour in both the teacher training school and the primary school. In the other schools 24 hours a week. Manual labour is obligatory to all pupils.”[33] For clarification: the planned total number of hours taught per day was four hours in primary education and five in teacher training. For the rest, concerning curriculum content, there would be a striking similarity between this project and the Projet d’organisation de l’Enseignement libre au Congo Belge published by the Ministry for the Colonies in 1925 and that was the first result of the activities of the Franck Commission.

The scheutist Rikken, who wrote a master’s thesis on educational organisation in the Congo, quoted extensively from minutes of meetings of church superiors, both in Belgium and the Congo during the period 1918-1919, from which it is apparent that minister Renkin was responsible for belling the cat. He wanted to search for new and preferably more general systems of subsidisation. According to Florent Mortier,[34] who was chairman of the meeting of missionary superiors in Belgium, Renkin wanted to find a system that “(…) could satisfy any government of any political leaning whatsoever. Moreover he wanted to take the number of missionaries, works undertaken and results obtained into account. Finally he considered that the State and the Government had a duty to subsidise the missions more extensively, this, with regard to the work in the peaceful penetration of education under all the forms undertaken by them. He believed that this measure was all the more necessary as the war had significantly reduced the resources of the missions and the alms of the faithful.”[35] In any event that seems to fit well with a statement by Renkin himself in a memo of January 1918 that stated, “Granting subsidies is based on a simple promise. A political upheaval – this war is an example – may dry up this source. It is essential to ensure a more solid basis for this important work.“[36] That again indicates that there was an issue very early on regarding the concern for the position of Catholic education in the colonial context. That attitude was also apparent at a meeting of the church superiors in the Congo itself: “It would be better to ask the question today even under favourable conditions rather than exposing ourselves to a new struggle for schooling in African territory.”[37]

However, that did not mean that people were willing to accept any system. The missionaries specifically strongly resisted any interference by the state with regard to content. The fact that the missionary-inspector would have to comply with changes in the syllabus, timetable and methods imposed from above, as intended in the London project, was too much.[38] The first intention of the missionaries at this stage was to preserve their absolute authority and their absolute freedom with regard to education. The bishops in the Congo also assumed a much more combative and uncompromising attitude than the church superiors in Belgium.[39 Mortier tried to keep the church in the centre in a letter to the Congolese meeting: “We believe that it must be noted that the meeting at Kisantu seems to have been mistaken of the true scope of the unofficial and confidential positions by the ministry under the administration of Mr Renkin. We would like to point out that it simply relates to starting talks preliminary to a project for a new division of subsidies and to lead the superiors of the missions to formulate their proposals in complete freedom. It would be a mistake to consider this as a sign of less respect for the work of the missions as such or as a risk to the freedom of education. The offices have already revised the document on multiple occasions after our own suggestions and they have shown themselves willing to follow up on any later observations.”[40]In any event it indicates that up to that point any form of general inspection or systematic regulation had been missing and that the financial support for missionary activities was realised unofficially via individual contracts and requests.

This is confirmed by other sources, cited by Lefebvre.[41] He claimed that the school convention of 1924 did not result in the first state intervention, or the first subsidisation of missionary education. This statement is not strictly incorrect but some of the conclusions Lefebvre drew in relation to the organisation existing at that point do make it possible to reduce the scope of that statement to the correct proportions. With regard to the system of ‘acceptance’ (and consequently of subsidisation) mentioned by the various parties involved and also by minister for the Colonies Renkin, he claimed: “A first condition for acceptance was the acceptance of the curriculum drawn up by the State. It may be assumed that this only related to an approval of the curriculum, as the curricula of the various accepted schools were not identical. … That is even clearer from a letter from Reverend Fr. Declerck, who submitted a curriculum for approval and from a letter from the Minister to Mgr. Roelens in which the Minister approved a curriculum.”[42] Even if, when interpreting them, strong account must be taken of the context in which such statements were made (Lefebvre was himself a scheutist, and the thesis was written in the fifties and consequently in the midst of the school struggle), it may still be deduced from it that strategic reasoning was present very early on with the Catholic missionaries in relation to their position in the colony.[43] Education then seemed an efficient lever to reinforce that position. The critics of the colonial regime and the missions consequently also emphasised the fact that the main intention of the Catholic missionaries consisted of evangelisation and not education, which was, moreover, not denied by them, …

Whether the London project proposal consequently had a decisive influence as such on the activities of the Franck Commission is not clear as yet. However it was cited by De Jonghe, who was clearly one of the decisive figures in the commission, in texts that were used as basic material. Except for this project text there was also a text written by De Jonghe himself and another project text by Florent Mortier,[44] a text that was drawn up following the colonial congress of 1921 and the report by the Phelps Stokes Fund on education in Africa.[45] This not only confirmed the predominance of catholic opinion within the commission. It also makes it clear that the supporters of adaptionism could make their influence count in relation to the concrete, contextual form of education. The Phelps Stokes report included an intense plea for adapting education to the concrete living conditions of the Africans: “The wholesale transfer of the educational conventions of Europe and America to the peoples of Africa has certainly not been an act of wisdom, however justly it may be defended as a proof of genuine interest in the Native people.“[46] The term ‘adaptation’ as defined in more detail in the report rather meant that account must be taken of problems set by the specific context and the specific environment, than that one had to use and show respect for traditions and customs, characteristic of the local population. The introduction of good hygiene, thorough training in agricultural techniques and the development of a healthy and good housekeeping fitted in that picture. For example emphasis was also placed on the fact that the participation of girls in education was much too low and that girls’ schools were urgently needed, which would be primarily geared to the preparation of food, and then to ‘household comforts’ and thirdly to caring and feeding children “and the occupations that are suited to the interests and the ability of women.”[47] The report also considered a number of concrete cases, including that of the Belgian Congo. De Jonghe had a French summary drawn up of that section and also had it published in the periodical Congo.[48] In the report that was published on ‘the education and training of blacks’ in the report book of the second colonial congress of 1926 and that was undoubtedly also seen by De Jonghe, the readers were referred to the Phelps Stokes report with the reference “They will see there that the English committee recognised an educational policy conforming to that which has been summarised above.”[49]

In the light of the other texts used and which were limited according to De Jonghe to four texts (Phelps Stokes, ‘a’ text of his own, the report of the permanent committee of the Belgian colonial congress and the London proposal), that statement must be interpreted with great circumspection. Recent research has indicated that there were real contacts between Louis Franck and Jesse Jones, the editor of the Phelps Stokes report.[50] They met in 1920, in Sierra Leone, before Jones travelled to the Congo. Franck supposedly used that opportunity to mention the idea of education in the native language, an idea that was allegedly later adopted by Jones and which was also present in the report. The adaptionist approach in general was also common to both. It consequently also seems that the guidelines from the foreign report were referred to on numerous occasions to give more weight to personal political choices.

The Franck Commission would finally make a number of recommendations relating to the principles on which Belgian colonial education should be based. The education was to be attuned to the environment of the Congolese and was not to start from a European perspective; moral education was much more important than (technical) education; education was to be given in the native language as much as possible; the cooperation with the missions with regard to education was to be given absolute priority.[51] The missions were clearly the means, par excellence, on which the government wanted to rely for the development of education in the colony. As De Jonghe stated: “This policy should be preferred to that which would consist of organising an official educational framework. The latter would be very expensive for the Treasury, would not ensure continuity in educational practice, continuity which is an essential component for success and on the other hand, as the budget available is limited, would not succeed in reaching the majority of the natives.”[52]

The conclusions of this commission were published in a project text in 1925, projet d’organisation de l’enseignement.[53] However a final version of the curriculum was only produced four years later. As indicated the work of the commission also resulted in the conclusion of conventions between the state and the ‘national missions’, which assured these of subsidies for twenty years in exchange for the provision of education. Because they had to comply with a number of conditions it almost always related to catholic missions in practice.[54] Protestant missions were, after all, almost without exception, foreign of origin and could consequently not comply with the nationality requirements imposed. This conclusion met the preoccupation already mentioned that was formulated by the Catholics immediately after the First World War to minister Renkin. The missionaries were concerned with truly securing the financial means made available to the missions. Until then there had only been a verbal undertaking to subsidise, which was indeed to be brought in line with the general obligations for the protection and development of evangelisation, as resulting from the international legislation. However any true legal basis was lacking. Ironically the liberal Louis Franck would consequently provide this basis, through the De Jonghe conventions.

1.3. The educational curriculum in 1929

The curriculum that resulted form the work of the Franck Commission, contained a rather modest educational structure which predominately provided for primary schools. A distinction was made between schools in the centres européens and rural schools. The latter were given a minimal curriculum and a duration of two years. This could be longer in the centres. The brochure in which the curriculum was published would quickly become known as the Brochure Jaune, a term that was also used for the curriculum itself.[55] The text of the Brochure Jaune is clear: “The educational curriculum in rural schools must be based on generalities so that it does not restrict the scope of application. In a vast country like the Congo, a detailed, precise and restrictive curriculum could not be enforced uniformly. An average curriculum must only be given, which may be adapted to different environments. It may be brought into practice under the direction of a teacher with a barely developed literary training, provided that he is truly earnest about his educational vocation. In primary schools established in centres and close to the teacher training colleges, the part played by literary education may be more important.. Here it relates to preparing the pupils for more advanced studies.”[56]

Schools in city centres or at central missions could also be given a second grade, where motivated pupils from the lower grade could continue their education. “Pupils in contact with a European element will have a greater ambition to become educated; often their ascendants are in the employ of the Europeans and they will encourage their children to go to school.”[57] Furthermore the curriculum clearly shows that the members of the commission were conscious of the fact that they were creating a number of problems themselves by arranging education in this way. Specifically selection, which really had a purely utilitarian objective, was approached with some concern. The authors assumed that everyone would not finally end up in those études plus avancées and that there would consequently be a kind of surplus of better-qualified young people. That was to be absorbed by ensuring that the training could also be useful for those people and that was possible by emphasising willingness to work and practical skills: “Consequently they must be given an education that is useful in itself and that will prepare useful men in the native environment. The habit of regular activity shall be a valuable tool for all. The same importance must also be placed on practical exercises as in the rural schools.“[58]

In addition these schools had to serve as preparation for further specialised studies. The pupils which started those would in any event have to work with Europeans and the brochure emphasised that they had to be prepared properly for that: “The recommendation is to insist even more here on the respect due to authority, to the European residents and to their property. The headmaster would do good work by stimulating feelings of mutual assistance and cooperation by means of causeries (rhetoric) and written assignments. Group role-plays should be organised and aimed at the same objective. It is best if theoretical precepts are used to develop honesty and propriety; they give the ability to make prompt decisions and encourage self-esteem.”[59] Schools that continued beyond the usual two or three years provided in the curriculum, were called école spéciale. These schools were intended to educate people who could work in sectors for which too few white workers could be found: office clerks, teachers and craftsmen.

The main lines of the content of the curriculum for all these schools were also set down in this publication. The subsidies and inspection, active intervention by the government in this educational structure were considered here. In any event the comment added to the detailed content of the school curriculum is telling: “Designed as they are, the curricula appear applicable in all schools. In cases of need it would nevertheless be permissible to deviate from them. The Government inspectors, in agreement with the missionary inspectors, shall decide on any changes to be made to the Curriculum. They will in any event ensure that the modifications would not be such as to remove specific sections of the curriculum or significantly to reduce the quantity of matter to be taught.”“[60] This assessment follows almost directly from comments relating to the smooth application of the curriculum indicated in the account of De Jonghe’s travels. In other words a significant amount of space was left for interpretation and the concrete execution and there was no absolute authority from the state with regard to the implementation of the curriculum. The cooperation and agreement of the missionary inspectors was required for that.

Consequently, the system of inspection also showed the considerable power to of the missions. It has already been stated that inspection and control had been the biggest problem in the realisation of general regulations. This is expressed in the concrete organisation. An official state inspection was introduced: one general inspectorate in Léopoldville, together with provincial inspectorates in every province (four at that time) and in the mandate regions. In addition, at least one missionary inspector was appointed per ecclesiastical circumscription. The state inspectors were responsible for direct inspection in the official schools for the Congolese. In the other Congolese schools the inspection was carried out in the first instance by the missionary-inspector, who would then have to report to the state inspectorate. In reality the official inspectorate did not amount to much: after administrative reforms in 1933 the department was reorganised to such an extent that only three regional inspectors remained in office in addition to the central chief inspector and his deputy.[61] Liesenborghs, who was (had been) a state inspector himself but was also clearly in the Catholic camp, wrote in this regard in 1940: “It may be hoped that the establishment and organisation of the official educational inspection, which is an essential element for progress in the field we are concerned with, may be the object of special concern of the Colonial authorities. In the same way, the missionary inspectors must be chosen with extreme care and must receive suitable preparation for the delicate task entrusted to them.”[62] It is difficult to establish whether this really implied a very subtle criticism of the operation of the inspectorate. In any event it is clear that the missions had succeeded in integrating a buffer in the system which made it very difficult for the state to intervene directly in their education and schools.

What were the main accents in this curriculum? The basic subjects were religious education, arithmetic and reading. In addition most attention was given to so-called leçons d’intuition, intended to familiarise the pupils with the most divergent subjects (parts of the body, flowers, tools, etc.) and which was based on question and answer patterns. In addition there was causeries (rhetoric) and the more specific subject hygiène, which were both to be considered leçons d’élocution. The following didactic guidelines were also given in the brochure: “In general, the teacher shall start by a concrete and dramatised account. For example, he may choose a child, who becomes the hero of all the narratives and who sees and does everything the teacher wants the pupils to see and do. He shall increase the adventures in such a way as to give his stories new matters of interest. After the narrative, he shall proceed to an analysis and summary, graduating his questions in the same way as he does in intuition lessons.“[63] In addition the subjects ‘Singing’ and ‘Gymnastics’ were also included in the curriculum.[64]

Two subjects must finally be mentioned separately. Remarkably enough the curriculum also provided a course in Français for the first year of the first grade, but it was optional. The brochure does not consider it in detail but references may be found here and there. The language in which teaching was given was already a problematic issue at this stage. De Jonghe had already stated in his article in Congo that the educational language used should be dependent on the concrete environment.[65] The reactions from the missionaries in the account of his travels also leaned that way. The proposed curriculum from 1925 assumed that the Congolese should be taught in their local language (dialecte indigene) insofar as possible. The lingua franca could replace that local dialect if it was close enough to it.[66] It was claimed that education in a European language was against all principles of educational theory. Teaching one of the Belgian national languages (as a part of the curriculum) was finally only foreseen in schools for the second grade. It was only considered obligatory for urban schools, but was optional for rural schools. The issue of the educational language was dealt with in a single sentence in the final curriculum from 1929: “Education may only be taught in a native language or one of the national languages of Belgium.”[67] It may also be concluded from this that the freedom and space for interpretation for people in the field was extended considerably. However, a lot of confusion arose from the fact that the introductory remarks with the curriculum also stated: “Even slightly developed literary education to children from rural regions would be of little use. It is sufficient to teach them reading, writing, arithmetic in their dialect.”[68] This only related to rural primary schools and the formulation does not seem to imply any obligation. In any event it is clear that French was not supported as the educational language.

Furthermore, it is striking how much attention was actually spent on manual labour and agriculture. It seems to have been a foregone conclusion that the education of the Congolese would include a considerable amount of manual labour, in any event, regardless of the situation or specialisation of the schools. The principle in the curriculum was that at least one hour must be spent on manual labour each day (and as already mentioned a school day was no longer than four or five hours) and that was usually an agricultural activity. However, that requirement also had to be met in the more urban areas. For that reason considerable attention was paid in the text of the curriculum in relation to the material infrastructure which the schools had to provide.

In any event this was a first curriculum implemented generally and imposed on the schools from above. This was the first time the state acted in a regulating way even if we may reasonably assume that the catholic missions were able to exercise considerable influence via the administration which was almost completely of the Catholic persuasion. Looking at the composition of the Franck Commission is sufficient for this; seven of the eleven members were clearly of the Catholic persuasion. Four of them were direct representatives of the missions.[69] We may assume that there was a de facto consensus on the existence and content of this curriculum. After all, the missionaries had been involved to a great extent in defining the content. Explicit financing undertakings were concluded for the first time between missions and state. Moreover these undertakings were explicitly linked to the nationality condition and consequently implicitly to the Catholic character of the missions.

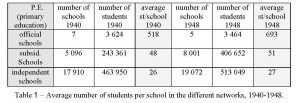

1.4. Application and consequences: quantitative development of education

Taken together these elements ensured a very favourable context for the missions. Consequently a considerable flow of money was quickly initiated from the state to the missions. Four million Belgian Francs were already allocated in subsidies in 1926, thirteen times the amount allocated in 1924.[70] Missionary education gradually expanded during the thirties. Quantitative data relating to the evolution of education must however be considered with care. That will be shown clearly from the overviews given below. It is predominately difficult to find correct, complete and general data for the period preceding the introduction of the conventions and regulations. Reference may be made in that context to the statistics from the N.I.S. (National Institute for Statistics) which did refer to the situation of colonial education from 1926 but only gave a few general estimates in relation to Catholic and Protestant education.[71] In the edition of 1927-1928 reference was made to the agreements concluded (the De Jonghe conventions), but apart from that only a few very incomplete figures were given. The consequences of the De Jonghe conventions were already making themselves known, in the sense that the comment was made that no account was taken either of schools that no longer complied with the curriculum (i.e. “rural schools for which the curriculum is limited to teaching the rudiments of reading and writing in addition to religious education”), or with schools run by foreign missions.[72]

In 1938 the N.I.S. published detailed figures relating to colonial education for the first time. No data is available for a number of the war years after that and figures were only published on an annual basis from 1945. Other figures were given in the Annuaires des missions and in a number of independent articles in the specialised press.[73] Some of these figures are given in appendix 1. There are a lot of differences in the presentation and composition of the groups and/or data presented, which makes it exceptionally difficult to draw up general overviews over longer periods.

Even if their accuracy must be handled circumspectly, the overall trend that becomes apparent from these figures for the thirties is relatively clear. Catholic education, if it needs to be said, made a great jump forward. This must be related to a great extent to the huge increase in the available budget. As already mentioned this was the immediate effect of the conclusion of the De Jonghe conventions and that is again illustrated in the figures cited by Liesenborghs in this regard, from which it is clear that the share of the total colonial budget that was paid in educational subsidies from 1926 was one percent higher on average than in the previous decade. Where the share of subsidies had risen by 0,85 percent between 1912 and 1925 to 2,33% and was approximately 1,6% on average, it suddenly jumped to over 3% in 1926. Despite a reduction in the mid-thirties, their share continued to be almost 3% on average until the war.[74]

2. Further development of the educational system

2.1. The thirties

This school curriculum was quickly modified and a new version was written in 1938 but was only applied after the Second World War. Traces of correspondence between the Brothers of the Christian Schools and the minister for the Colonies Rubbens,[75] indicate that there was some insistence for modifications and reform of the education available.[76] Following this insistence a certain Brother Melage was sent on a study trip, and this trip and the report he made about it were used to legitimise the draft of a new curriculum.[77] This draft planned the further division of the types of schools. Paradoxically two different directions were taken: on the one hand the further implementation of generalisation, on the other side specialisation. The minimum curriculum was simplified even further. In addition a so-called ‘selected’ second grade was introduced in addition to the ordinary, one in which the education would become more theoretical, where teaching would be given in French and where it would be possible to prepare for secondary education.

This draft was only applied after the Second World War.[78] In the meantime the development of the catholic mission schools continued unabated. The catholic authorities in the Congo strongly resisted anything that could break their monopoly of education.[79] This also indicates that they were conscious of the fact that this was an exceptional position, which could be attacked. In a previous study I have already stated that the demand for education outside the catholic network had already been on the agenda before the Second World War.[80] Yet at that time little could be seen of that in practice. With the exception of a few disparate initiatives, the monopoly of the missions remained intact. Nevertheless the decision-makers were considerably concerned in that period by possible initiatives against this monopoly, as is apparent, amongst others, from the correspondence within the administration. It had already been noted in the Parliamentary Commission for the Colonies that there was a lot of appreciation for the work provided by the missions but that an important marginal note should be made: “It should be understood however that this adhesion in principle may not be considered a road to the monopolisation of education by the missions. It is our country’s duty to seek and further develop the assistance which it receives from independent education in the colony. But this is only a part of its duty. It must on its part increase its personal initiatives for public instruction and must, while avoiding a spirit of competitiveness, pursue the development, which now seems in a terrible state there, of official education in addition to independent education.“[81]

However for the time being the catholic missions could rely sufficiently on their entente with the colonial administration and secure their position of authority in that way. This position of authority could in theory be threatened on two fronts. On the one hand there were the Protestant missions which had also been present in the colony from the beginning and had even taken the lead in the initial period in the evangelisation of the Belgian Congo. On the other hand there was the fear of the establishment of an official and neutral educational system that would drain some of the financial means available to institutions not under the influence of the church.

2.1.1. The Protestant threat …

In the first instance it appears that the Protestants were not really considered a great threat. They were sidelined by the De Jonghe conventions, which had actually also ensured that their presence in colonial education stagnated, while Catholic education grew exponentially. Although a de iure monopoly was never explicitly mentioned, this was certainly what the Catholic missions had considered. This is proven by the opposition to awarding equal rights, which Minister Godding had intended to introduce in relating to subsidies after the Second World War. The Protestant missions had, nonetheless, opposed the de facto discrimination against their people with relation to the Catholics long before the Second World War. The joint spokesman for the Protestant missions, the Conférence des missions protestantes au Congo Belge[82] had already expressed the wish, in the early thirties, to be recognised and treated on an equal basis with the Catholic missions. Correspondence on this matter makes it clear that the administration had, for a long time, taken the same line as the catholic missions and that they simply continued to refuse to remove the discrimination. In 1932 the then Minister for the Colonies Tschoffen[83], was confronted when visiting the Congo with a memorandum on behalf of the Protestants which asked for a review of the policies of the Belgian government with respect to the Protestant missions and their task in the colony. When the representative of the Protestants wanted to come and defend this memorandum personally to the Minister, in Brussels, he was, in fact, promptly referred to the head of the administration. The administration refused to review its position. The question was finally laid before the King himself in 1934, through Emery Ross, the chairman of the International Missionary Council.[84]

In internal memoranda Edouard De Jonghe strongly emphasised the fact that no obligation existed to subsidise the Protestant missions. The argument made by the Protestants, arising from the obligations set down in the Colonial Charter and the Charter of Berlin, was disregarded in the interpretation of the Colonial administration, these texts only contained an obligation to encourage mission work in general. It could not in any way be inferred from this that an obligation existed to treat everyone involved in mission work in the same manner. The consideration of such questions or not was completely under national sovereignty. And although there was therefore absolutely no obligation, the government could change to supporting foreign (and therefore also Protestant) missions. But, as De Jonghe put it, the government had then to understand that it took a large risk: “If we were to yield to these two desiderata, it would then result in us subsidising foreign missions. And such a policy could seriously compromise the Belgian influence on the Congo. Belgium and its national missionaries are not powerful enough to fight with equal weight against the combined forces of foreign educators. Our educational organisation is still rather weak and imperfect.“[85]

2.1.2. … actually a foreign threat.

The administration, and particularly De Jonghe, was therefore clearly very apprehensive that Belgian sovereignty would suffer, even a considerable time after the Congo had been taken over by the Belgian state. Indeed, it did not seem illogical that a territory eighty times larger than Belgium was hard to defend against possible foreign interests or aggression. Moreover, the bond, which existed between the Protestant missions and the Anglo-Saxon world, only added to this distrust. Great Britain was interested in the Congolese territory from the first and this interest continued after the First World War. According to De Jonghe:”The periodic blooming of similar movements is always to be feared in the Protestant milieus because the Anglo-Saxon Protestants cannot get away from three characteristics that form their origins, namely: Free examination of dogma, the scriptural basis of their moral education, i.e. the Old Testament where the prophets rail against the oppressors of the chosen people take a major place and finally, the spirit of opposition against the work of Leopold II which is still traditionally the case with the Anglo-Saxons.“[86] It was sometimes embarrassingly clear that the local administration in the Congo also took a dismissive and even disapproving attitude towards the foreign missionaries. In a memo from 6 January 1931 the inspector-general for education wrote to the vice-governor-general: “There would moreover be a means of freeing ourselves from the requests from the Protestant missions: introduce a condition for obtaining subsidies in teaching French and in French from the 3rd year. The majority of the Protestant missions are dissatisfied people without any culture and who shall never know any French.“[87] We can also refer to the ‘Belgianisation’, which was organised in Katanga, because of the considerable influence of the English language exercised there through the large compagnies.[88] In any case it was clear that the colony must remain free of foreign influences, and must receive as much Belgian influence as possible: “The colonial government must affirm its right to reserve government subsidies only for those schools committed to teaching subjects that are loyal and faithful to Belgium.“[89]

2.1.3. Secularisation

We have already referred to the attitude of the permanent committee of (Catholic) heads of the missions in the Congo, from which the concern for the Catholic character of education is clearly shown. The continuation of a system of subsidised education was greatly preferred to a parallel network of official schools, even though the leadership was systematically entrusted to congregations of religious. Here too, the message was that the existing system could be put at risk by a turning of the political tide.[90] The government had to be discouraged from organising official education, populated by religious orders (“brothers”). The fact that the government at that moment, in 1919, had already asked four congregations of religious to lead official schools, was in itself alarming enough to decide: “The government is gradually embarking on the road of public education.“[91]

This total freedom incidentally ensured that the missionaries opposed every form of interference. Inspection by authority was also considered a bad thing. The government must give them money and then leave them alone, trusting that education was in the hands of experts. It is very significant that this expertise in no way rested on any educational qualities. This was also stated quite plainly. If the government was to provide lay teachers, then these would place much too much emphasis on sound character from a theoretical and educational point of view of education (which in their eyes would come down to emancipated education). And that was just what the Congolese did not need: “It is important to draw the government’s attention to the excessive tendency to educational theory in some administrative minds who believe they can see the secret to new prosperity in the colony through education. Education should be encouraged, certainly, but it must be done so with care. (…) Uprooting the native from the soil and manual labour would be to ruin the Colony and commit the native to misery. Education is almost always educational theory at excess.”[92]

Thus, two movements were already visible before the Second World War. On the one hand there was the increasing concern of the government, who went from giving absolute carte blanche to the missionaries, to a more programmatic attitude. This was logical, because the budgets also began to rise, and the motherland was groaning under an economic crisis. On the other hand, from the Catholic side, there was very conscious consideration of how to strengthen and maintain the position of power that had been built up. This monopolistic attitude was questioned by the Protestants above all, and to a lesser extent by the freethinkers. The fact that matters did not lead to open conflict was due to several factors, of which the first is certainly – and it must not be overlooked – the limited interest for the colony on the home front. Apart from that, every protest still bounced off the wall of Church and State, which worked together in union, not least because of an administration predominately made up of Catholics.

2.2. Reform of the curriculum of 1938

2.2.1. Reform

In addition to the political and economic necessities, of which the importance for the evolution of the educational system is not to be underestimated, there was naturally also the implementation of the content of the 1929 curriculum. Melage’s report from 1936 contained a number of remarks concerning educational practice. Among these, it was pointed out that the curriculum taught at that time was above the capacity of the Congolese. As far as language education and mathematics lessons were concerned, both had to be more practical and concrete and one had to move away from the excessively theoretical concepts being taught, for the Africans did not understand them at all. After all, it was said they were intuitive beings, who reasoned instinctively. That did not mean that it should be assumed that the Africans could not be educated, that they were unable to do any studying. The few exceptions who made it to priest or moniteur proved that it could be done. The blame for the relative failure of education had to be sought in the content and interpretation of the curriculum. The curriculum applied was reported to place much too much emphasis on instruction instead of training. This message seems rather contradictory, but can probably be explained on the grounds of the more general point of view that the reporter made with respect to the Congolese or Africans. He did not consider them immediately equal to the whites. For example, whenever he talked about ‘native’ art, according to him too much value and meaning was ascribed to it. According to him the plastic art of the Congolese did not succeed in expressing feelings in a successful manner. What some people called expressionism, he just considered failure. The African was, in his view, a born imitator and had no higher feelings or ability for abstract thought.[93] That this opinion was widespread, and also shared, for example, in the administration, is apparent from the statements that Depaepe and Van Rompaey collected.[94]

The newly developed curriculum was already introduced into the field in 1938. That is apparent because of, among other things, the fact that a circular was then sent, signed by governor-general Ryckmans and the chef de service of the education department Welvaert. That memo, addressed to the heads of the missions, asked that they should gain knowledge of the new project and to let him know by return whether they were in agreement or not. Clearly the first reason for the curriculum not being applied immediately can be found here: probably not everybody could or would simply agree to this text and in this way they drifted into the war period. Nonetheless, this text was known. In the thesis by van Steenberghen which has already been cited, a (partial) comparison is made between the texts of the 1925 project, the 1929 curriculum and the 1938 text. This last text is described as a “rewriting of the brochure jaune which was provisionally tested and undoubtedly finalised then.”[95] The ambiguous status of this new document is also evident from a remark of the scheutist father Maus in an article in Congo, at the end of 1938.[96] He first remarks that the Gouvernement Général had just published a new curriculum, and names the 1938 curriculum explicitly. At the same time he indicates a remark in a mission newspaper of 1936 from which it is apparent that there was already a new curriculum being applied then, ‘as a replacement for the Brochure Jaune.[97] The phrasing used by Liesenborghs in 1940 makes it possible to deduct that this was not the case officially, and that a new curriculum would only officially come into force in 1948: “The organisation currently established (1929, JB) still governs public education for the natives in the Belgian Congo. Some modifications to detail are currently planned. They have been pompously called a reform. This description is at least exaggerated as it apparently does not in any way effect the general economy of the system that will be studied in this article.”[98]

This remark could at that moment have been a correct evaluation of the facts but with hindsight this seems to be a sort of intermediate phase towards the post-war changes to the education system. What were the most important changes in this proposal, and how were they regarded? The most important changes were indicated in the circular to the heads of the missions. With regard to the duration of the education and types of school, the duration of primary school education was kept to five years. A sixth, preparatory year was indeed created, for middle school education. Furthermore, the distinction between rural and urban schools was maintained, moreover with a new division into central and ‘subsidiary’ schools (dependent on the presence or absence of a mission). The education in the rural primary schools remained preferably ‘restricted to generalities’. From the second grade a strengthening in existing curricula was provided for, as a preparation for the so-called écoles moyennes or middle schools, which now received a broader scope than the already existing écoles spéciales, where only administrative assistants were educated. These schools were now given a longer curriculum (four instead of three years), but that did not apply to the teacher training colleges where the fourth year was optional.

In theory these new provisions substantially lengthened the maximum school time; instead of a maximum of eight there was now a maximum of ten years.[99] But the intention was certainly not for this to be general for the whole population. The main point of attention of the curriculum reform was with the primary schools of the second grade. According to the new brochure the best pupils from the first grade in the rural schools, together with the pupils from the urban schools should be brought together here (consequently provision was literally made for a first selection in the rural schools, while that was not so for the town schools). There was, however, an important reservation: not everyone who began the second grade would succeed in getting into middle school education later. This was why it was necessary to make sure that the school would give good preparation for the others, who were expected to be the majority,[100] for a life that was supposed to be lived in the region of origin.[101] For those who succeeded in getting into the second grade, education was provided that was aimed at providing a good general development, on the one hand and to provide a direct preparation for concrete tasks on the other, which were described as “junior office positions in the employ of administrative, industrial and commercial bodies in the Colony.”[102] And as far as the écoles moyennes were concerned it was assumed that the pupils who successfully proceeded to and finished at these schools, would come into common contact with Europeans. Consequently it was also necessary that they would look decent, and that they would have good deportment. They had to be Europeanised to a certain extent. They were then supposed to wear European clothes and eat at a table with a knife and fork.[103]

Girls’ education was handled separately in the new brochure. That was really the most important difference with the 1929 curriculum. A certain differentiation between the curricula was created from which it seemed that education for girls would be systematically less broad than that for boys. For the first grade schools the boys were systematically referred to with the remark “The same curriculum as for the boys’ school, except for the following points,” where then only the course on handicrafts was indicated, which was filled in differently. This was also the case in the first year of the second grade, with the understanding that for a number of subjects a more limited curriculum was provided for girls (arithmétique, système métrique and leçons d’intuition). In the second year that difference became more outspoken. For example boys had to learn to count to a thousand, girls only to one hundred; boys had to learn measures of area, girls did not… The French course also differed at that level, in the sense that a broader vocabulary had to be learned for the boys from the second year on so that they could be given certain courses (such as arithmetic) in French from the third year. In the third year of the second grade the difference became greater still and while yet a sixth preparatory course was organised for the boys, this was the end of the ride for most girls. Besides the more general system of middle schools for boys there was only the domestic studies school for girls, an education of three years consisting only of subjects that had to do with learning domestic skills. The teacher training college also had a separate section for girls and here a similar system as in primary education was being applied: for a number of subjects the curriculum for boys was indicated, for a number of courses (those regarded as difficult or ‘literary’) a more limited curriculum was provided.

2.2.2. Reactions

The scheutist father Albert Maus, who was known as a fervent advocate of the adaptation principle, was the only person who publicised a thorough analysis of the new curriculum, not coincidentally in the periodical Congo. His point of departure was that retaining and developing the difference between mass education and elite education was a very good thing. In this context he found it very good that the curriculum literally took over a number of principles from the 1929 curriculum. In fact he really regretted that the original text from 1924, directly based on the text of the Phelps Stokes report, was not implemented. According to him, this still contained the most crystal clear arguments for the civilising role of the school in Africa that could be found at that time. The following passage was the relevant one, as it appeared in the summarising article in the periodical Congo: “It would be futile to transport the Belgian educational organisation to Africa… The Congo requires a special educational organisation, properly adapted to the environment. In Belgium the school is predominately required to instruct. In the Congo it must above all educate… The principal aim of the educator must be gradually to improve native morals; this is more important than the dissemination of instruction itself… The formation of character through religious morals and customs of regular work must be given precedence in all schools over literary and scientific branches… Education must be limited to concepts which the natives may find useful in their economic environment… It must reach the greater majority of children.”[104] Elsewhere Maus stated that primary education of the Congolese had to comply with three qualifications: “universal, uniform and in the native environment“.[105] Unfortunately the 1929 curriculum had posed far too high demands. Happily the new curriculum, according to Maus, simplified the syllabus of a number of subjects in the first grade. Concretely he referred to ‘Grammar’, ‘Metric system’, ‘Drawing’, the disappearance of French as a subject, the concretising of the arithmetic lessons, the expansion of ‘Causeries’ (rhetoric), and the introduction of ‘Modelage’ (modelling) lessons.

In the case of agriculture, however, he found just the opposite to be the case, and he found that it would be better that some theoretical lessons could be given in the lower grade, which was now almost completely limited to practical applications. Maus reasoned as follows: seeing that agriculture was traditionally a female occupation, the men were very contemptuous about it. The idea was to make agriculture more interesting by associating it with a certain reward in the form of one’s own yield. Whether this was realistic is another matter. On the basis of the description which was used it seemed more to do with yields which in the first place would benefit the mission, and not directly the pupils themselves. Further, the author drew parallels between the intellectual level of the Congolese and that of the masses in nineteenth century European society; to show that too intellectual an education was to be avoided. Maus himself nevertheless considered himself a moderate, and as a conciliator between two extreme tendencies, of which the one stood for a much more theoretical, and the other for an education directed exclusively towards agriculture (the professor at Leuven Leplae was used as an example of this).[106]

The author again found it a good thing that the more intellectual education should now be further limited to the schools situated in towns. The old brochure had also provided for this broadened education in the lower levels of the teacher training colleges, but since these were often situated in the countryside, it was really superfluous and even counterproductive to provide too complex subject matter. After all, most of the pupils there would surely not come into contact with Europeans. Even at that time the more advanced education was still systematically designed to meet European needs. Maus’s criticism of the new curriculum was mainly directed towards the internal contradictions. On the one hand a noticeable strengthening of the subject content was provided (for a number of subjects more subject matter was provided, or the subject matter was much more comprehensive or better structured). On the other hand the curriculum proposed that the pupils should get an education which would make it possible for them to fit in with the traditional social structures. Maus considered this nonsense and he was probably right in this criticism. The double aims that were demanded of the second grade education were clearly contradictory.

His criticism was really not directed towards the basic principles of the curriculum. The option to make a distinction between mass and elite was not questioned, unlike the hybrid character of the second grade as it now existed, because this would preclude being able effectively to attain the goals set. Maus proposed to move a number of subjects from the second grade to the first and vice versa. Supplementary to this he also suggested for the new second grade to split de facto into a ‘heavy’ and a ‘light’ version. The light version had to follow on from the simple first grade, directed at the masses, the heavy version would then serve those regions (particularly the urbanised areas) where streaming the pupils towards higher education was more in line with expectations. The principle of selection was very close to Maus’s heart here. To avoid as much waste (literally “déchets“) as possible, the selection had to be applied as strictly as possible between the first and the second grade. Concomitant with that, the qualities reached by the pupils must be taken into account, but also the preset quotas. He did feel instinctively that such a selection mechanism would lead to problems: “We will not be able to stop the rise of a schoolboy who has done 2 or 3 years of primary education, it will be even harder after a complete 5 year cycle.” But the intended elite training must in any case remain limited to a certain (and limited, above all) number of people.

Objections to the hybrid system to be organised also came from others. The fact that further education would be limited led to problems, as was said by scheutist fathers working in the province of Kasaï.[107] It was assumed that people would be attracted to the central schools and would try to avoid the subsidiary schools. As a result the school age would increase again, because in order to allow their children to go to a central school where there was more chance of further education, many people would let their children travel greater distances, so they would wait until they were old enough. Perhaps it is indeed significant that Maus represented an opinion quite different from the ones in Belgium; He assumed that the Congolese were fatalistic and obedient. If there was no selective education or further education for the people in the countryside, the people would learn to live with it, he supposed. If one only decided soon enough where someone was to be allowed to study, he would be satisfied with it: “Seeing a rare opportunity for emancipation definitively escaping him he would leave it, undoubtedly a little discontent, but not bitter or demeaned.”[108]