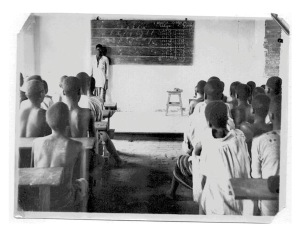

When Congo Wants To Go To School – Educational Practices

In this chapter the focus shifts slightly to didactic and educational practices, insofar as these can be known. This is used in the meaning of every day interaction between missionaries, moniteurs (teaching assistants) and pupils. The inspection reports give some insight here into what really happened, although in most cases from a distance. Although the reports and letters from inspectors may be said to be perfect examples of the normative, this does not mean that they make it possible to see clearly what practices were criticised and for which practices alternatives were offered. Two contrasts that were discussed earlier appear again and ‘mark’ distinctions between them. The first is the distinction between the centre and periphery, which, in this context coincides with the dichotomy mission school – rural school. In the previous chapters it was obvious that the material situation was very different depending on whether a school was situated at the central mission post school or a bush school. The second contrast between the two types of teachers, missionaries or moniteurs corresponds largely with the mission school – rural school situation. These distinctions are, in fact, situated almost entirely within the context of the central mission school, considering that, almost by definition, no missionaries taught in rural schools.

In this chapter the focus shifts slightly to didactic and educational practices, insofar as these can be known. This is used in the meaning of every day interaction between missionaries, moniteurs (teaching assistants) and pupils. The inspection reports give some insight here into what really happened, although in most cases from a distance. Although the reports and letters from inspectors may be said to be perfect examples of the normative, this does not mean that they make it possible to see clearly what practices were criticised and for which practices alternatives were offered. Two contrasts that were discussed earlier appear again and ‘mark’ distinctions between them. The first is the distinction between the centre and periphery, which, in this context coincides with the dichotomy mission school – rural school. In the previous chapters it was obvious that the material situation was very different depending on whether a school was situated at the central mission post school or a bush school. The second contrast between the two types of teachers, missionaries or moniteurs corresponds largely with the mission school – rural school situation. These distinctions are, in fact, situated almost entirely within the context of the central mission school, considering that, almost by definition, no missionaries taught in rural schools.

However, they do not correspond completely. Ideally, it should be possible to identify three different situations within the context of (Catholic) missionary education: A first situation in which pupils received education without any, or only sporadic, intervention from missionaries. This is what was found in rural schools; a second situation, in which a moniteur gave lessons in a central mission post, near to missionaries but not in their permanent presence; and a third situation in which the missionaries exercised permanent control over what happened in the class or gave lessons themselves. This third situation was, as should already be clear, quite unusual (except in the initial phase of a mission post). In a number of cases one subject was given systematically by missionaries. Usually that was religious education. In other cases one class, and usually the highest one, was entrusted to the care of a missionary. This occurred mostly from necessity because no native teacher could be found who was suitable for the job. In girls education there were, relatively speaking, more female religious who actually taught themselves. This must be explained by the fact that female education was way less developed because of the social context in which Congolese girls functioned and because of the position of the female religious workers themselves.

The organisation of this chapter is not, in fact, along these lines. The available sources were, after all, almost exclusively produced by the missionaries themselves. It also seems to me to be difficult to deal in an even-handed manner with situations in which the missionary staff were absent and to give them, quantitatively speaking, just as much space as the others. For this reason another approach was chosen. It starts from general observations or questions (“topics”). This is probably less structured but at the same time also ‘more honest’ towards the reality studied in the sense that it has been decided beforehand to start from one particular aspect, to collect information about this and to discuss it, but without causing the reality to ‘stop’ at a particular moment. In any event this approach is easier to grasp because in this way we avoid telling a too compartmentalised story, whereby for each of the three proposed hypotheses the same topics would need to be dealt with again and again.

Discipline

1.1. The school rules: theory…

In principle every school had to have school rules: “In every class there hangs a set of rules for the Colony: there is a lot on it, 20 numbers composed by the Father Director of the Colony himself. Get up … attend Holy mass… Work… school… eat… go to sleep… and so forth…“[i] The scope of the rules probably differed strongly according to the place and the congregation that was active there. A very interesting example for the study of classroom reality is the rather comprehensive rulebook of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, created for the Groupe Scolaire in Coquilhatville.[ii] In theory, the Brothers had been given responsibility for the pupils during school time but in practice their reach went further. The rulebook contained a mixture of instructions that was directed at the moniteurs and the pupils. It constitutes a very normative source, to the extent that we can expect it to effectively reflect reality for a large part. The book begins with a list of provisions that applied to the teaching staff. It applied to their behaviour and also to their tasks with respect to the pupils. Among these, a lot of attention is paid to religiously inspired themes. After a few indications for the maître chrétien himself (enough prayer, be punctual, make sure that the timetable is respected), there follows the first chapter “éducation chrétienne“. Reciting the correct number of prayers a day, the use of a rosary, going to mass and confession at set times: it was the task of the teaching staff to make sure that the pupils certainly did these. “Enseignement” was only mentioned in the second section. Here, a number of items were discussed in connection with the teaching method, from which not very much can be deduced about the reality. The teacher must follow the curriculum and make an effort to pass perfect knowledge on to the pupils: “He shall carefully prepare his lessons and give methodical and graduated education. He shall apply himself to cultivating the intelligence of his pupils as well as their memory and language.”

The importance of good manners, external behaviour and appearance were underlined again in this section: “He teaches a course on etiquette and takes any opportunity to teach the pupils politeness.” An aspect that was comprehensively covered after this, in the second section, was the “règlement disciplinaire“. Further, a number of formal, administrative duties were set down, such as keeping lists of attendance and the checking of absentees. In one of the rules it was also expressly determined what the moniteur was not allowed to do:

The teacher must refrain:

- from hitting, mistreating the pupils, from giving them unjust marks;

- from keeping the pupils after the regulatory school hours, from removing a pupil from the class and sending him home without the approval of the headmaster;

- from writing any discourteous note or expression on the pupils books;

- from preventing a pupil from taking part in examinations;

- from sending the pupil on errands outside the school, even for things related to the class;

- from smoking in the schoolrooms in the presence of pupils;

- from reading newspapers in the playground and especially in the classroom;

- from writing his classroom diary or preparing lessons during school hours.

Extract 1 – Restrictions laid on the teacher. From the school rules of the Brothers of the Christian Schools in Coquilhatville. Source: Aequatoria Archive.

The first section ends with the list of prayers that must be used in the classroom and with a few quotations about “la récompense du maître chrétien“. These quotations were undoubtedly intended to be motivating. The motivation was not supposed to come from the pay but from the moral satisfaction that flowed from the work of a teacher. Finally there followed the text of the morning prayer for the teacher, which must be prayed before the beginning of every school day (“To nourish his faith, fan the flames of his zeal and in order to receive the light of heaven he needs to guide the children, the teacher will fervently recite the ‘teacher’s prayer’ before school each morning“). In the second section purely disciplinary measures are mentioned. Not that there was nothing said about order and discipline in the first part, but here the behavioural rules for the pupils were set down, while the first part was presented more from the teacher’s perspective. In a number of paragraphs the different aspects of the required behaviour were revealed: entering and leaving, diligence and work, behaviour in class, “classe et classique” (meaning class equipment, JB), order and discipline, playground and recreation, behaviour on the road, cleanliness and politeness, behaviour at church, apologetic and polite expressions.

Order, discipline and self-control were the leading principles in the text. The pupils must always show self-control, they had to fulfil the pattern set down for them both with regard to movement and language. What had to be said, what the pupil had to do and how he had to do it were set down for all forms of communication with adults. If a visitor came into the classroom, the pupils knew what they were supposed to do. They had to stand up and, preferably in chorus, pronounce the appropriate greeting: ‘Some visitors occasionally said: Good day children’ or ‘Praise to J.C.’. The pupils responded: ‘Good day sir…’ or ‘Amen’.” They had to stand up in a particular way: they must look at the visitor modestly and show by a “smiling physiognomy” that they were happy to receive a visit. It is not at all clear what that implied in practice and if it was always done effectively as it was set down. After they had seated themselves again, they must pay attention to the visitor if he had come to say something: “Having sat down appropriately with their arms in the resting position, all eyes and ears were turned to the words of the visitor, who would address them.”

The rules also included prescriptions for behaviour during lessons. The pupils must sit calmly at their desks and should not bother their neighbours. To ask something or to give an answer they must raise their right hand, without snapping their fingers or making other noises. When being asked questions the pupil should stand up next to his desk, “a straight back, head turned towards the teacher, a smiling face“, and answer with a loud and clear voice. Apart from this the rule prescribed silence, order and neatness. It was also prescribed what the pupil was allowed to do outside. That was not much: on the stairs or in the gangways there must be no running and no talking, shouting or whistling. On the playground the same applied: the rule determined that the pupils must play. It even suggested quite strongly what should be played: “The games to be used are ball or Foot-ball (sic).” Also, during play pupils should avoid lying on the ground, pulling each other or fighting. The same rule continued: “Fisticuffs are not to be tolerated.” The pupils must also not hang around near the toilets.

Even outside the school the pupils had to follow a comprehensive code of behaviour: in church but also in the street. A chapter “Behaviour at church” explained how the pupils had to behave at church, how they should come in and how they must sit: “At their place they will worship and avoid making any noise, they will bear themselves appropriately while kneeling or sitting and shall look towards the altar without turning their head from one side to the other.” Again, a strengthened form of discipline applied in the immediate neighbourhood of the church. Playing was not allowed around the church, even before the start of the church service. On the way to school or home the pupils must retain their dignity above all. A number of things were bad, such as “Shouting, racing around; throwing projectiles or giving way to all other misplaced fantasies.” They must greet all those who held positions of superiority with the appropriate respect (and those were particularly priests, religious workers, teachers, all Europeans and the parents of other children). They must above all be helpful. They must show the way for strangers, though without walking with them. Finally, to streamline contact with the outside world even further, this publication listed a number of summed up formulae for politeness, which the pupils were to use in all kinds of circumstances when speaking to adults.

1.2. …and practice?

It looks very much as if people wanted to control what happened in the classroom and even the behaviour of the children outside the classroom as much as possible by fixing it in formulas and procedures. It remains difficult to judge whether this corresponded effectively to reality, or if it remained a wild dream. The guidelines and rules are recognisable in so far as they were also applied in Europe. Just as in nineteenth-century Belgium corporal punishment still existed in spite of all the fuss and the objections that were made about it, also in Congo corporal punishment was still used, even though it was usually against the rules. Jos Moeyens reported such a case in 1934. Somebody called Bolawa, a moniteur in one of the rural schools, in the area of Bamanya, went further than he was allowed to. Paul Jans had him put on the spot for this. According to the report by Moeyens the person concerned had afterwards pulled himself together: “According to the chief moniteur, Louis Nkemba, this moniteur is more ready to take orders and has paid attention to the remarks that were made by the Father P.Jans, rector of Bamanya, and so has delivered evidence of his goodwill. He beats the boys less and when he is teaching explains the lessons better.”[iii] The fact that people here speak of ‘less’ shows that the missionaries had nothing much against a slap being delivered now and again. Only in extreme cases such as this did they have to intervene. In Flandria there were similar but less heavy complaints from the director Frans Maes: “Moniteur Ngola, who is very enthusiastic and competent, has to learn to moderate his expressions and not to react too heavily, for example with Lingala sentences and expressions, as if he was a policeman! I had already mentioned this to him.“[iv]

Again in the number of other cases it is not as clear whether corporal punishment is being referred to or less severe forms of punishment. For example, in an article in the Annals about the school of Mondombe: “‘Petelo’, asked the Father, ‘why haven’t you been to Mass today?’ Without fear but still somewhat abashed he replied ‘Fafa, I was sleepy and too lazy. Was that not a frank answer? Then was heard, severe and earnest: ‘come to my office after school’… The office of the Fafa! .. Very many father-like admonitions were given there. It is sometimes more effective and far-reaching with just two people. In any case, it was certainly good for Petelo. Still, the children know the Father not just as the ‘Man of discipline’.” What is to be understood by this last expression is not completely clear. The Fathers were certainly against the teachers giving the pupils physical punishments. The Pierre Bolowa mentioned was reprimanded and threatened with dismissal. Another moniteur from a rural school in the area was also tackled by the missionaries because of complaints about hitting pupils: “The moniteur: gives a relatively good impression, is clean and tidy. In the presence of the Father and the head he is rather timid in the classroom. It is said that he teaches regularly and well but at the beginning he hit which had caused a few of the Batswa children to run away. The Father reprimanded him on this subject in the presence of the head and the head catechist, reminding him that the school management formally prohibits hitting pupils. If punishment is required, he can send him to the Chief.“[v]

1.2.1. Order and punishment

Order and punishment often went together, for example when working on the field or on a plantation. Jos Cortebeeck writes in one of his articles about the coffee harvest. The Sister on duty kept her eyes open and checked the delivered work of the schoolboys systematically: “At 11 o’clock the coffee gong was beaten and you saw the boys, baskets on their heads, coming from all sides of the coffee plantation, singing and laughing to their mama, by the drying boxes. The Sister busy with the coffee takes the register very carefully, and anyone who has not enough gets a mark and for every mark bakotas (10 cent pieces) are taken away from the week’s or month’s money.”[vi] In the mission of Mondombe the boys had to work in the mornings in the fields, for example in the peanut harvest. This activity was also carefully checked. Rightly, according to the writer of the article: “The Father whistles, it is a signal for the end of the work. Those from the nuts must first be checked. ‘Arms up! …” at this command everyone stretches their arms up and more than one peanut falls to the ground. After that is checked behind the ears. There our head finds more than one unpeeled peanut. Embarrassed they leave.“[vii] The pupils often had to provide their own food, either completely or a great part of it. It was therefore not so surprising that they used all the possibilities of doing this. They used the pauses between the lessons but sometimes they had to go about it in the evenings too, although to do this they had to disobey the rules about curfew.[viii] At the start of the 1930s the state inspector observed that in Flandria the pupils often stayed away for a few days so as to gather rations.[ix]

Taking food belonging to the missionaries without permission was certainly punished. Another quotation about the mission of Flandria shows how this happened: “Fafa Octaaf has dark but sharp eyes and quick hands. Once he caught two schoolboys who were eating from the ‘botanikken’ of the Sisters. He caught them by the scruff of the neck (collar we would say) and put them on their knees in the courtyard in the view of everyone. In front of them were spread the few remaining fruits. ‘Yes you terrible naughty boys, I will send you to Ingende; this afternoon the administrator will come and throw you in the pen! You can wait here on your knees.’ After an hour or so Father Octaaf came to see …[x] The ‘botanikken’ referred to the Sisters’ garden and the fruits that grew on the trees there. The pupils were not allowed there. This was also complained about in other places: “We were not allowed to climb up to search for palm nuts because it belonged to the mission, if not we would be sent from school or punished. We had to go behind the priests’ territory. We collected all the nuts that fell. That was behind their territory. Even the fruits that fell, good grace, you had to be sure that you weren’t seen collecting them!“[xi]

The Fathers were obviously persons that you had to look out for, at least in the view of their Congolese pupils. In the articles that appeared on this in the Annals, that was never said explicitly. In certain passages there was so much emphasis placed on the disciplinary character of the school experience that this almost automatically raises questions about the way in which order and discipline were imposed: “And this school of 400 boys, you don’t hear them, not even in their quarters of stone houses, one house per village, you don’t hear them, you see them in the church but you don’t hear them: there is discipline there, they are drilled, there is a power under it, the secret of the two Sisters, who never hit, never shout, now and again one just moves her head.”[xii] It certainly shows that in a number of cases the disciplinary rules, just as in the example of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, were also applied effectively. That is also apparent from the story already told about Sister Imelda: “Remember that for our new boys it needs a lot of effort to live according to the rules day-in day-out without falling short. The Father likes order and discipline. That is necessary with this gang of rogues. The Father takes care of lighting the fires of diligence under them. Now and then he comes in the school and it is not always to congratulate but also sometimes to ‘reprimand’.“[xiii]

From the point of view of the Fathers that was really just one side of the coin. They also saw themselves as rewarders. The following quotation about this comes from the same article and shows that there were indeed other methods used to bring the young people to the right path. Giving the expectation in the future of particular material benefits to be awarded not only constituted a permitted method to get the boys to do what they wanted them to. The point system referred to here clearly illustrates that the control by the missionaries was applied over a very broad area: black marks could be received in the church, at school and at work. Frans Maes reported somewhere that he had developed a specific point system to ensure better discipline. Obviously, black marks were given out for disobeying the rules, but these could be cancelled by the pupils and there was the possibility in any case of ‘earning’ good points. In this manner, the community also benefited from it: “DISCIPLINE: left something to be desired at the beginning of the school year. This explains the large number of pupils being sent home, at least amongst the older boys. By applying the system of buying back the bad points by voluntary work, I have obtained a good result and at the same time the levelling of the football field was finished faster than planned.”[xiv]

On a certain day Father comes into school and says: “it is already fourteen days since the school has begun… everybody knows the rules and I am going to reward those who keep strictly to them.” And in every class he showed a pair of beautiful trousers, in a khaki colour with a pocket on the side; and with it a leather ‘nkamba’ (belt). beautiful… really beautiful… Everybody wants them and in their imagination they are already at the distribution ceremony of these beautiful trousers at new year. Still so much time to wait and to never be naughty. Oh, that is something else! That is not for everybody. The older ones have understood quickly. (…) They are so excited they are unable to make any noise, and they look at their neighbours as if to say: “shall we really all get such nice trousers with a belt and a pocket in it?” One of the worst dares to ask the Father just that. The answer is: “The ones who do not get a single black mark will get them at the next holiday.” They are disappointed and their heads are full of questions: “Fafa, is there among the 250 boys only one who will be the lucky owner of the trousers with the nkamba?” The Father has read the quandary from their faces and reassures them, with the assurance that there are many of these nice trousers. And then the diligence is awakened. Now to work. (…)

The first month has passed. The Father comes to the school with his register and very carefully this time the black marks are counted up, those from the prayers, those from the school and those from the work. Those that only have one bad mark are forgiven but the others get a big disappointment: their nice trousers are gone and lost forever.[xv]

Extract 2 – Sister Imelda about the motivational techniques of the Fathers (1937). Source: Aequatoria Archive.

1.2.2. Nature of the punishments

Punishments frequently had a utilitarian character, which can be seen from a number of testimonies from former pupils: “We had to go and look for wood or sticks as punishment if we had to be punished for something.”[xvi] And: “There was a punishment, you had to cut so many square metres of grass. Ten metres or twenty or fifty in length and four metres wide. It had to be cut, eh, and this wasn’t like the lawns we have, it was grass that was taller than us. Or, during break we had to cut fifty pieces of firewood, these were called ‘fascines’.“[xvii] And the missionaries also confirmed this. Fernand Van Linden, who was headmaster in Flandria:[xviii]

Was there much punishment?

FVL: Yes, there was punishment. Gathering wood or getting the food ready. Getting the manioc ready for the women. Or weaving baskets.

Was that really punishment for them?

FVL: Yes, Yes, some days they really wanted to go fishing or hunting but then they had to gather wood.

And if they did not want to do it, would they object?

FVL: Then they could go home.

And they wanted to avoid that?

FVL: Hey, yes![xix]

These types of punishment were also used with the girls: “I was given punishment: for one week I had to cut the grass. I was not allowed to go to class.“[xx] Although this sort of punishment was used conspicuously, the nature of the deserved punishment differed from mission post to mission post and probably depended on the amount of inspiration of the local Fathers. When asked whether there were tasks and chores set as punishment, Stéphane Boale, a former pupil of the school in Bokote, said in the affirmative, at first: “Yes, yes, (very affirmative). Clearly. Work with the coupe-coupe. Tidying the terrain. Yes, or sweeping, things like that.” When asked about possible other types of punishment he said: “That is to say, they all had numerous ways of punishing people. A disruptive person would be expelled if it were serious. If a person did something else, for example with regard to the lessons, if they had not done their homework they were told: “you must write one hundred lines of this or that during your free time.”[xxi]

Nothing was ever published in the MSC publications about real corporal punishment in the sense of beatings. A number of people said that the chicotte was still used in other regions until after the Second World War. At the Sisters in Leopoldville: “They beat you with the chicotte (cane) in front of your parents so that you would not start again.”[xxii] In Stanleyville: “And during our time, I must emphasise to you: the educational theory of corporal punishment was in force. If you were lucky, when you arrived late or when you were caught talking you would only be shouted at but generally it was the cane, you see. You see that shows something of the relationship we had with the teacher.”[xxiii] That was obviously never done in the area of the MSC. No traces can be found of the cane either with the Fathers or the Brothers. In any case, it was expressly stated in the rules of the Brothers that physical punishment was forbidden; only work was provided as a disciplinary measure.

This is not to say, however, that this always corresponded to reality. The moniteurs made the children kneel down as a punishment, or sent them out of the class (in which case they also risked punishment by the missionaries, if they were in the neighbourhood): “Did the moniteurs give a lot of punishment or penalties? Yes! To correct a person they had to be punished. And what were these punishments? For a disruptive pupil? They were made to kneel.”[xxiv] And some teachers did, in fact, hit the children: “Being hit did happen, as it always had an effect on everyone. But usually it was prohibited.”[xxv]

Even the missionaries used different sorts of punishments. Suspension: “If you arrived slightly late, even by five minutes, you would be excluded. So, for example, in the boarding school of the Moniteurs, you were not allowed to talk during the night. The Father supervised there. If you talked and that was found out, it was over. You would be expelled, even during the night.”[xxvi] More physical punishments were also used by the MSC. We have referred previously to statements in the letters from Father Vermeiren, from which it seemed that pupils were hit from time to time. Jean Indenge told of Father Pattheeuws, who came to work at the mission of Wafanya in 1951. His presence was experienced as a welcome relief by the pupils because he, much more than the others, concerned himself with hygiene and feeding the pupils. There was one problem: he kicked the children and punished them: “Every Sunday after Mass, he would inspect the pupils to see those who were not clean. And he would kick those who were dirty. And then the punishment.”[xxvii] These things often happened with the best intentions, from the (biblical) principle “that the rod should not be spared”.

That is also apparent from the anecdote that Rik Vanderslaghmolen told about the school in Bokuma. The primary school there was under the leadership of Father Gaston Heireman. When he built new sanitary installations for his pupils, the following happened: “Gaston came to me one day and said: “Come and look at my new WCs. They’ve all wiped their bottoms on the corners!’ That was really dirty! I said: ‘Gaston: don’t worry about it, it will get better!’ And I had some mortar standing, for I was busy with building. And I took this mortar to the WC, and mixed up quite a lot of pili-pili with it. And I spread this mortar rather thickly on the corners. And the next day we heard the boys running from the WC to the river, yelping. Oh dear, Gaston was really sorry about that. And I was really sorry for what I had done, because he was sorry. That his little boys had so much pain on their bottoms.“[xxviii]

1.3. ‘Trouble in paradise’

It is perhaps not obvious at first sight that the interaction between missionaries and Congolese should not be interpreted one-sidedly as one of patient leaders and obedient or at least docile pupils. Still, a number of indications can be seen. In the previous chapter reference has already been made to a number of conflicts in which the MSC, or some people under them, were involved during their missionary work. There are a number of references to conflicts between missionaries and teachers. We refer here to another conflict, of which many fewer traces are to be found. The events occurred in 1943. In a letter to Mgr. Van Goethem, Father Wauters mentioned a ‘revolt’ by the pupils. A number of the bigger boys who were at boarding school in Bamanya became rebellious and had broken curfew by making extra noise after the second sounding of the gong instead of keeping silent. In spite of reprimands by the missionaries during evening mass they repeated that behaviour on other days. Wauters revealed the case in detail. The way in which he reported the facts gives a completely different view of the relationship of power between Fathers and pupils.

After the second “lokole” (gong) they began, just as on the previous evenings, to make still more noise and to throw stones on the tiles of the colony house. I went there myself and P. René came behind. When the boys saw us coming in the moonlight a group of them ran away behind the side of the colony building (the married people’s side) and began to throw stones at us. We fled up to the veranda and the boys who were on the inside square of the colony were quiet when they saw me. Throwing stones on the roof lasted a few more minutes. The big boys, who were there with me, said that it was the children of the married people. I sent them after the stone throwers but they claimed not to have been able to catch any. Then I called the chiefs of the boys and the third class of training college to my room. They insisted that the stone throwers were boys from Bamanya, those of the married couples or those that were lodging with the married people. But the next day they went and told Brother Director that they had not accused the children of the married couples but that I had done so. (Br. Director naturally believed the boys but not the Father.) So with this opinion and going by what the boys of the third year teacher training had told me, the next day before the Mass I called the boys of the married people out of the desks and made them all kneel down in the choir. After the Holy Mass I told them that I was putting them all out of the class. After school the parents came to palaver. They swore up and down that their children were innocent, that it was the boys of the colony themselves who were guilty. Their children went to sleep in good time, they said, and they did not allow them to run around after dark. I began to doubt the guilt of these boys and then I told the two catechists and the five moniteurs to investigate and come and tell me the results. The outcome was that the children of the married people were innocent and that the incitement was from the biggest boys of the colony. (…) When the case was finished, I made the boys who sleep in the colony work all day as punishment. When, in the afternoon after work, they had been to the river and were coming back, on the way they did nothing other than curse the married people with the foulest “bitoli”. When Father René that same evening went to serve a dying man in the village, he was catcalled by a group of boys from the colony as he went by. Then the boys ran away. Then I forbad the boys from the colony from taking the sacrament. The next evening the boys were quiet but when Father René went to his room he found the keyhole of his door blocked up with pieces of wood, so he had to work for a long time until he could get it open. The next day he found his door had been written on with chalk. It made fun of his baldness.[xxix]

Extract 3 – From the letter of Father Wauters about the ‘revolt’ of the students (1943). Source: Aequatoria Archive.

In spite of this it appears from other witnesses that the curfew was strongly applied. Jean Indenge says the following about a curfew in Wafanya and the punishments connected to it: “A 8 p.m. the bell went, to go to sleep. And then the principal moniteur would call an assembly. If he missed a person – and it did happen that he missed people – older boys who had slipped away for two reasons, one of two reasons. Either they had gone fishing at night – but nobody would tell them that. Or the head moniteur thought perhaps they had gone to the city to look for women. We were 12, 13 years old so that wasn’t our problem. But there were some who were 18 and then they had to be supervised! An absence like that, obviously, that meant being suspended. Not having spent the night inside.“[xxx]

This story is situated in the 1940s, and it happened in a more isolated mission post, whilst in the incident reported above it was older pupils who were involved, in the neighbourhood of the ‘big’ town. At that moment the pupils had the courage to act against the Fathers, although not enough to do it openly. The authority of the missionaries over their daily affairs was still strong enough to keep them disciplined. In this a number of intermediaries such as moniteurs and catechists were also called in, these were close to the missionaries and had themselves a certain measure of authority. According to the testimony of former students this situation also evolved. There are however absolutely no traces to be found of cooperation between moniteurs and pupils in the missionary sources we consulted. Jean Boimbo declared though, that private lessons in French were given by the teachers to the pupils outside school hours.[xxxi]

The missionaries must have been somewhat alarmed, however. In inspection reports complaints were sometimes found that there were deviations away from spoken language. Hulstaert and Moentjens sometimes referred to the use of French during and outside the lessons or also to the wrongful use of French by the Brothers but had never talked about the systematic teaching of French by moniteurs. The reprimands for such situations certainly did not occur only with the MSC. Also in other regions the language that had been chosen for education was strongly adhered to, made as obligatory as possible and, indeed, there were frequently punishments.[xxxii]

Rhythm

2.1. The rhythmic passing of the school day

2.1.1. The pupils’ drill

One of the first accounts of the course of a school day may be found in the Annals of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart from 1927. Marcel Es described his work at the mission school in Boende and began with the morning gymnastics of the pupils: “Then the morning exercises are especially useful to bring in some liveliness: the teacher ensures they warm-up. It goes with ‘apparase de repos! En posisson! Un, deux, twa, quat! En ava! en arrière’.” (…) “But once they are at work together they forget all their small miseries. Then everyone dances forward to the rhythm of their singing: and then they feel no hunger, no thirst, no tiredness or pain, until mouths and arms fall still.” (…) “Then it is time that the fafa whistles them together to go to the class in ranks. A and o, and e, and i, and u, that goes well; 2+ 2 = 4 and 3 – 1 = 2, that goes well too. But when it gets more difficult or if the class lasts too long for their taste – and that is quickly the case – then their heads get so tired! Some I have to wake up from a soft, pleasant nap.“[xxxiii]

If anything can be deduced from this report, then it is the importance attached to drill in the school. In the mornings there was an assembly with physical exercises, in groups. After this came the work and here, too, the rhythm and disciplined character of the activities was very important. It is an element that is always present in the stories and reports. For example, in the account by Sister Godfrieda published in 1934 in the Annals: “Every two hours… lokole! Each person jumps up praying and then goes his own way. Then back to school… The road to the village is black with boys! Quickly the small bell tolls that calls them to the line; they saunter to their places amid great chattering. The main bell!.. they fall silent. Sr. Ghislena is standing on the veranda and orders: ‘fiks!’ and seven hundred and fifty pairs of arms go down… ‘Bum’bakata!’ They fold their hands… ‘A fina!’ They pray a Hail Mary, and then they all go into their own classroom.“[xxxiv] The lokole or gong played an important role in de school day, for the most important dividing moments were marked by it, as the school bell did elsewhere.

The former Trappist Brokerhoff also began his description of the working day at the mission post of Wafanya with physical exercises: “After completion of the daily exercises, which last about half an hour, the morning tasks of the missionary are interrupted by a half-hour rest.” (…) “It is in this break that one really enjoys the Congo.” The break was probably for the pupils to go to mass, or to wash themselves. “Just at half past six or a few moments before a small bell rings in the refectory. It is time for breakfast. In the meantime the tasks of the day are prepared and discussed and after a quarter of an hour this first operation is finished. A pipe is filled or a cigarette is lit and one is ready for the show to begin. Now you hear the word Ngaga! (the bell) and the big bell in the hallway sounds. Twelve good strokes and the person who has sounded them, one of the table boys, rushes like the wind to the tam-tam and, helped by one or two of his friends beats with all his might to tell everyone that work – manual work for the older ones and school work for the small and middle-sized – is starting.”[xxxv] In the teacher training college in Bamanya there was a similar routine in the early 1950s, as related by Jean Boimbo: “But I was a domestic, a server for the Brothers. What I had to do, preparing food (…) When we left Mass, we had a kind of cupboard, chests, there were three of us, working for the Brothers, serving the Brothers. The chests always stayed there. The Sisters prepared omelettes, the lunch. (JB: That had to be carried?) They were given to us. The Brothers ate and once they had finished eating we cleared everything up. At eight the bell went and we had to go to class.“[xxxvi]

Next, pupils were assembled. This was also done in a quasi-military way: “Approximately 20 minutes after the beating of the tam-tam they are pretty much all there. In the boys’ quarters the scholars and the big boys stand, separately, in two straight lines. The two teachers for the first, and the capita (headman) for the second, stand to one side or behind them. They hardly see us coming before a command rings out and everyone stands in ranks with the little finger lined up with the seam of their trousers. I go to the middle, just in front of the picture of the Sacred Heart, look around to see if everything is in order and say loudly: ‘A Jina’, at which everybody makes the sign of the cross. Then in the Lonkundo language ‘Do you believe in Christ (Fomemi a Jesu Kristo) and all answer aloud ‘Bideko l’Adeko’.” (…) “Now it is the turn of the schoolboys. Assembly is held in the same way for them. Then when all the names have been called off there is the command ‘fiks’ and they stand there looking at the ‘fafa’ and now a half-hour of exercises can start.“[xxxvii]

That quasi-military character is not a gratuitous interpretation. The missionaries, after all, frequently called on soldiers to take care of the physical condition of the pupils. That was certainly the case in the early years of missionary activity. The Daughters of Charity called on the services of an army sergeant during the first school years in Coquilhatville to take care of the physical education.[xxxviii] A military man was also hired in Mondombe: “Albert Bomanga, a former corporal, gave gymnastics each day at quarter to seven.”[xxxix] It was also common practice later, in which, according to a circular from Hulstaert from 1939, the administration also cooperated: “The administration has announced that the cooperation of soldiers is available, especially with the idea of teaching moniteurs gymnastics, so that they can stand on their own feet later. It would be best if the local school management asked the army command concerned (or the A.T.), at least in places where there are soldiers. In the case of important garrisons, instruction can be given by officers and NCOs, so long as it is necessary to train the native moniteurs. The lessons should take place at most twice a week, preferably from 4 to 5 pm.“[xl]

Frequently, the missionaries considered these exercises to be a separate part of the day, not part of the education, although from 1929 it was included in the curriculum. In 1930 Petrus Vertenten wrote explicitly in his inspection report about Mondombe: “The time given for gymnastics and the experimental garden cannot be taken during lesson time.”[xli] This same thought also comes through in the introduction of the following quotation from Brokerhoff: “When the gymnastic lesson is finished, school begins. Divided into three classes our little curly heads sit on the school desks to sharpen up their understanding with all sorts of subjects connected with education. Reading, writing, arithmetic, song, geography, introduction to weights and measures, drawing, French, there you see the daily programme.” In the letter from Hulstaert that was just quoted it seems from the arrangements in connection with the time of the gymnastics lessons that he also does not consider it a part of the school day.

Discipline was often by far the most important element of the programme, although it was not listed as such. The Annals relatively often refer to the orderly and disciplined character of the pupils: “The clarion calls for the second time; in front of every classroom a double line of eager-to-learn youths forms. Here or there a chatterer dares say a word; but the chin of Sister Bernardine goes up threateningly and forces a reverent silence. Now the rows slowly push into the class.”[xlii] In inspection reports, too, order and discipline were invariably considered as important elements and it was emphasised how this was brought into class life in practice: “The attitude of the pupils: entering and leaving in silence and in a line without any disorder. In class they keep quite, straight, hand on the desk.“[xliii]

In articles in the mission periodical, the authors liked, probably unconsciously, to play on the difference between the natural disorder of the children and the order that resulted from the intervention of the missionaries. That can be seen, for example, from the same article by Brokerhoff: “When the first lesson, which lasts until 9 o’clock, has finished and the school bell has rung, they all storm outside to enjoy themselves with a ball or some other game or maybe to take a snack. A half hour break is always over too quickly for their taste; for when, a couple of minutes after half past nine, the bell calls them back into school, patience is needed until the last pupil is present.”[xliv] Another example, from Father Caudron, again in de Annals of the Sacred Heart: “You were standing chattering and cackling, calling and shouting: the last stroke of the bell sounded and in an instant all the noise stopped and you stood like drilled soldiers stock-still in the ranks. That was discipline!“[xlv]

2.1.2. The (school) timetable

As present in the sources as the element of discipline is the use of time, the division of the school day into blocks. The lesson times were regularly interrupted to relax, to go to mass or to eat but the actual lesson time was six hours: two times one and a half hours in the morning, and three hours in the afternoon. The ‘rhythm’ of the school day, the division into relatively short lesson units, was typical because it was assumed that the restricted attention span of the Congolese children had to be taken into account. This opinion was very widespread, so much so that even at the start of the 1950s the colonial educational administration distributed a note to all school directors, Recommendation for the establishment of daily timetables, in which rules were given for splitting up the school day.

It is recommended to take the following into account insofar as possible for school management:

- Plan lessons that require more concentration in the morning and insofar as possible at the beginning of the day or after a break. Courses that require an intense intellectual effort from the pupils certainly differ according to the type of school; in any event it may be said that subjects relating to mathematics, writing, explained reading, grammar and systematic exercises in observation and speaking certainly belong to this category.

- Avoid excessively long lessons (partly ineffective insofar as they exceed the attention span of the pupils) and lessons that are too short (for example in some subjects, like arithmetic, in which Congolese pupils are relatively slow).

- If a subject only has two lessons available per week, avoid putting them on two consecutive days.

- If studying a subject requires more than six lessons a week and if it is consequently necessary to put two courses of the same subject on the timetable on the same day, separate these two lessons with one or more subjects relating to a different subject area than that of the two lessons concerned.

- If it is necessary to arrange more than two lessons consecutively that require considerable attention from the recipient, have the pupils take some short physical exercise to relax between the lessons (a few minutes of easy gymnastics or rhythmic or free walking, or singing or simply a free break).

- Each time the morning lends itself to it, include practical work during the lesson itself.[xlvi]

Excerpt 4 – From the circular on drawing up timetables, Aequatoria Archive.

This circular raised the disgust of Frans Maes. He noted a number of remarks in the margin of the article that reflect his irritation well. Concerning the attention span: “Who will determine that?” About recreation: “As though distraction could suddenly stop!” And on the slowness of the Congolese children in arithmetic: “Not just them, South African blacks too.” His indignation was partly based on research that he had carried out himself into the speed of the African children in arithmetic exercises. As a result of this note he carried out a supplementary test with children at the HCB school in Flandria. In the different classes he did a Bourdon test with letters.[xlvii] From this he concluded that even half an hour of concentration was not too long for the children: “The best performance was even reached towards the end of the ½ hour; so tiredness could not be observed! (naturally, if the effort is not demanded too often per day: e.g. 2x as a maximum for such efforts, which are in fact never demanded in ordinary lessons, even in arithmetic!).“[xlviii]

He repeated these remarks in a letter that he wrote to Moentjens.[xlix] Maes again rather strongly criticised the education officials who had composed the memo: “These worthy advisors are very mild with their advice but applying it in practice mostly causes problems that they don’t seem to concern themselves with. They just transplant Belgian rules here, without any previous study. And just what sort of rules, too… they stink of old parchment and school grind, of the irresponsible system of ‘sticking together like oat ears and chaff’. They seem to be quite some specialists giving you advice such as ‘place … the lessons that need the most attention after a break.’ Just as if these boys could go in a minute from relaxation to effort just through willpower.” However, Maes was an exception, probably under the influence of his university training (he had studied education for two years before leaving for the Congo).

Other missionaries seemed to have accepted the popular prejudices about the Africans’ capacity for understanding. On this we can refer to the pronouncements quoted in chapter 4. Especially in girls’ education and for the Batswas these sorts of difficulties were mentioned. Vertenten wrote about the girls in Bamanya: “The education is very intuitive. The R. Sister explains herself well in Lonkundo, she lives for her class. That is the secret of her success, which is considerable, when we know how difficult it is to keep the attention of young native girls.”[l] However, according to him that applied just as much to the boys: “One has to make their classes interesting in all sorts of ways, treating the dry material briefly and clearly, one can ask a short period of attention from them. Sometimes five minutes is already too much; if some begin to stare into space, that is the moment to change the subject before their eyelids close.”[li] Later these sort of remarks disappeared for the most part from the discourse and references to the characteristics of the Congolese became more vague, at least in the context of the sources on school life.[lii] Hulstaert wrote somewhat more carefully about the Batswa in 1939: “The school curriculum is regularly followed so far as the subjects are concerned, still the pupils cannot follow the prepared division of the material. But this is not so important. We have to adapt ourselves to the lower state of development of the boys. Certainly, the desire for a free life and the memory of it play a certain role in the difficulties of bringing the Batswa to the level of the prescribed curriculum.”[liii]

Still, the timetable used continued to show the same characteristics throughout the colonial period, fitting in clearly with the old-fashioned rules. Only in the initial period a much less structured curriculum was used in a number of places. In the initial phase the school in Flandria only provided three classes, where a complete subject was taught first before the next one was begun. The children first learned reading and writing, then they learned arithmetic. In the first instance Hulstaert (who was then the head of school) blamed that on the poor material circumstances: “The lower course is mainly concerned with reading and writing, the two others mainly apply themselves to arithmetic, at differing degrees, you understand. We have not yet been able to introduce the regular application of the planned curriculum. The circumstances simply do not allow it.”[liv] Hardly half a year later, however, he remarked: “I will content myself simply by saying that the situation is generally the same as during the previous term. The only facts to be noted are that the lower class has started studying arithmetic after having perfected writing and reading written texts.”[lv] Apart from this, school days passed according to fixed and rhythmical changes of subjects. Later, too, such systems remained in vogue in many schools of the vicariate. The examples that are reported here show timetables respectively from the boys’ primary school in Wafanya (1930),[lvi] the rural primary school of Mpenjele near Bamanya (1941),[lvii] and the boys’ primary school in Bamanya (1954).[lviii]

In Wafanya in 1930, the school day only lasted for half a day, all together three hours and a half per day. The school day was divided into two blocks, one of an hour and a half and one of an hour and three-quarters. They were divided by a break of one quarter of an hour. The first block was divided into three periods, one of a quarter, one of three quarters and one of half an hour, which did contain different subjects, however. Only the first period of a quarter of an hour was always the same: religion (and religious history, but that was of course a very homogeneous package). The second block after the break had only two periods but was all in all much more fragmented. The first period was no less than an hour and a quarter long but in that the most diverse subjects were taught, sometimes three successively. The second period was then only half an hour long and contained one or two subjects.

In the rural school of Mpenjele the curriculum guide of 1941 provided four blocks of a maximum of 60 to 75 minutes. The central point was the morning, with two and a quarter hours of lessons. In the afternoon there was only teaching for an hour and forty minutes. Of this the last twenty minutes were spent singing. Most time was spent on the subjects religion (40 minutes every day) and reading (45 minutes every day). Sometimes a whole hour was spent on dictation, but not every day. The other subjects took up barely twenty minutes each. The agricultural activity before starting the real lessons lasted, in fact, the longest: an hour every day.

The timetable from Bamanya for the 1950s was much more complete, which shouldn’t be surprising considering the year and the place. Still, here too, a number of guiding principles can be observed that correspond in part with the principles used by the administration. The largest part of the ‘theoretical’ teaching material came first, in the morning. As always, this was headed by the most important part, religion. All together, this lasted less than two hours. Subsequently, there was a second ‘cluster’, in which no religious work was expected: gym, recreation and handicrafts. The afternoon consisted of two hours of lessons: a first, more theoretical hour, but here again the second half was devoted to ‘lighter’ material (singing and causeries). The second hour was again filled with physical work.

Wafanya 1930: boys’ primary school (original in French).

| 8.00-8.15 | 8.15-9.00 | 9.00-9.30 | 9.45-11.00 | 11.00-11.30 | |

| Monday | religionreligious history | readingdictation | monetary and metric system | writingdrawing ornamentation

French 1/4h.° |

arithmetic |

| Tuesday | religionreligious history | writingcalligraphy | arithmetic | monetary metric system | readingdictation

|

| Wednesday | religionreligious history | calligraphydictation

French° |

arithmetic | hygieneintuition

the time wall charts |

readingdictation

|

| Thursday | religionreligious history | readingdictation | monetary metric system | writingcalligraphy | intuitiondrawing |

| Friday | religionreligious history | readingdictation | writingdrawing ornamentation | arithmeticFrench 1/4h.° | clock readingmonetary and metric system

geography* |

°1/4 of an hour French for the first year of the second grade.

*1/4 of an hour geography for the first year of the second grade.

—

Mpenjele 1941: primary school (original in Dutch).

08.00-09.00: agricultural work: manioc, peanuts, palm trees, etc.

09.00-09.40: religion

09.40-10.00: writing

10.00-10.15: playtime

10.15-11.00: reading

11.00-11.30: language, speaking

11.30-14.30: noon break

14.30-15.00: dictation

15.00-15.30: dictation or drawing

15.30-15.50: playtime

15.50-16.10: causerie – about plants, trees, objects, etc.

16.10-16.30: singing

—-

Bamanya 1954: first year primary school (original in French).

| Monday | Tuesday | Thursday | Friday | Wednesday | Saturday | ||

| 8.00-8.30 | religion | religion | religion | religion | 8.00-8.30 | religion | religion |

| 8.30-9.00 | reading | reading | reading | reading | 8.30-9.10 | reading | reading |

| 9.00-9.20 | cop. dict. | obs. eloc. | obs. eloc. | cop. dict. | 9.10-9.40 | obs. eloc. | recitation |

| 9.20-9.50 | arithmetic | arithmetic | metr. syst. | arithmetic | 9.40-10.00 | gymnastics | gymnastics |

| 9.50-10.10 | gymnastics | gymnastics | gymnastics | gymnastics | 10.00-10.25 | recreation | recreation |

| 10.10-10.25 | recreation | recreation | recreation | recreation | 10.25-11.00 | metr. syst. | arithmetic |

| 10.25-11.30 | agr. work. | man. work | agr. work | man. work | 11.00-12.00 | agr. work | drawing |

| agr. work = agricultural work | |||||||

| 14.00-14.30 | reading | arithmetic | arithmetic | reading | man. work = manual work | ||

| 14.30-15.00 | singing | hygiene | singing | causerie | cop. dict. = copying & dictation? | ||

| 15.00-16.00 | man. work | agr. work | man work. | agr. work | obs. eloc.= observation & elocution? | ||

Extract 5 – School timetables applicable at three different places and times. From Aequatoria Archive.

2.2. The rhythm of the lessons: reprise

The emphasis on rhythm and regularity is strongly evident in the lessons themselves. References to repetition, and to repetitive patterns, are legion. In 1939, Henri Adriaensen wrote: “Next door in the school the boys drone out their reading lesson together.” (…) “How quiet the mission is now. In the distance I hear boys singing songs in the school. Every afternoon they do that for the last quarter of an hour.”[lix] De Rop in 1947, about the mission of Imbonga: “14.00 h.: after the midday break: just go to check whether everybody’s at his place and if the school boys are back in the class. Yes, they are there, I can already hear the droning of the lessons.”[lx] Here in 1957 again, about the school in Bamanya: “The roof of the teacher training college shines in the sun. In one class the lesson is being repeated aloud. A moniteur taps his pointer on the board or on his lectern.”[lxi]

In the classroom itself, and in the context of the teaching activity, repetition was not only a means to discipline, but also an educational principle. There was a lot of repetition, both by the missionaries themselves and by the teachers. Many courses were partially repeated during the school year but this principle was also used when learning new subjects: “Repetition must really never be neglected, especially in subjects of general education, such as arithmetic, language, science. Not only should one repeat from time to time some part of the material to be taught but also in the meantime (in new subjects too) one should make use of favourable opportunity – just for a few moments – to come back to some point or another.”[lxii] This repetition, Hulstaert thought, was necessary to bring the pupils to a good understanding of the material to be learned. If it were to go too fast, they would not be able to keep up. This was, in fact, one of the more pedagogically directed points of criticism that he formulated with reference to the education by the Brothers of the Christian Schools in Bamanya: “We must make a few general remarks concerning the curriculum. We have been following what is common at the school in Tumba. However, this institution has 6 years of primary school. Consequently they are obliged to force the execution of the curriculum, especially for arithmetic. This situation is not beneficial to a good understanding of the subject matter and prevent it from entering into the pupils’ minds properly.“[lxiii] The school in Bamanya only had 5 school years and therefore work had to be done more quickly and there could be less repetition.

In his report about the Batswa school in Flandria, a few years later, he emphasised repetition once again: “Repetition of what has been seen earlier must be done regularly; otherwise the connection would be lost. The more often this is done the better. This is especially important in arithmetic and language. The metric system should be reviewed carefully in all classes because the foundations are lacking. The subjects of the 4 principal calculation operations also need to be revised, since they form the key to further arithmetic education and without this knowledge and those concepts one is left hanging. The boys will not, then, be able to enjoy arithmetic. The same thing applies, mutatis mutandis, for language teaching.”[lxiv] A few years later he came back to this again in his discussion of the girls’ school in Bamanya: “In general a lot needs to be repeated and improved if one wants to bring the highest class up to a certain level.”[lxv] He did, however, make a clear distinction between repeating material and the slavish repetition of things that had been learned. In an inspection report from 1944 he observed: “Right down to the lowest classes it is a joy to hear the children explaining Bible stories, for example, in a way that shows they understand what they are saying: it is something quite different from the slavish repetition which one sometimes hears in other schools.“[lxvi]

That slavish repetition was, however, very present in education, which is apparent from several remarks. Vertenten wrote in 1930: “For arithmetic the results still leave much to be desired. The children do not understand the problems they solve without fault but automatically and without having properly understood them.”[lxvii] Hulstaert himself remarked on it repeatedly. In a report about the girls’ school in Bamanya, in 1936, he wrote: “It is undoubtedly a model school. The Reverend Sister is completely dedicated to her children and is a sound teacher. The curriculum is completely adapted to the mentality and the level of development of the pupils. No bluff, no stuffing memories but a constant striving to make the lessons as practical as possible, to weave them into the thought processes and the emotional life of the children, in a word to stretch them to a real development of spirit and heart.“[lxviii] Too much memorising was also one of the things he accused the Brothers of. In 1944 he stated in his report about the boys’ primary school in Bamanya that in all subjects, there was far too much call on the memory, which was not good for conceptual understanding.[lxix] In the 1950s it was also regularly remarked, particularly in the little bush schools, that too much was memorised and that there was too much automatism in the manner of teaching. In the writing lessons too much was copied and in the reading lessons too much was automatically droned out.[lxx] Moentjens gave the following advice in a report from 1951 to one of the teachers in Flandria: “With the 2nd year the moniteur must also avoid reading-by-heart, especially by getting the weaker elements to spell the syllables and even the letters.”[lxxi] The same defect was also later commented on, both in well-established as well as in newly founded schools.[lxxii]

If the lessons were too repetitive in a number of cases there were undoubtedly various reasons for this. Sometimes the material circumstances of education favoured memory work and repetition. It was remarked in this regard in 1956 that writing was difficult in the rural school of Beambo. The pupils had no school desks and they had to hold their notebooks on their knees. In another case, the entire Lonkundo lesson was copied on the board. The teacher himself had no textbook, he had to go and borrow one from a colleague. The pupils themselves had no book. Other missionaries remarked that it was characteristic of the Congolese that they could work well with their memory and following that insight ‘repetitive methods’ were therefore often used. Sister Auxilia, who was greatly appreciated by Hulstaert, also used repetition methods in Bamanya. To her own account, she tried to get more out of that. In the biblical history lessons she started with using the wall pictures but: “Great importance is given to lively, though unaffected retelling of the lessons. 4th and 5th also reproduce the lessons in written form, with the help of questions.” Further, songs were also learned by heart. The pupils had to write down the text by heart, whereby starting points for causeries were identified, according to the Sister.[lxxiii]

Transmitting the teaching material

3.1. Teaching by observation

In several inspection reports the emphasis was strongly laid on the necessity of a more demonstrative education. Particularly Hulstaert used the term rather often: “Another remark should be made about arithmetic: this subject should be made more demonstrative, especially in the lower classes, and with more variety (abacus alone for example is not sufficient). In different classes this defect is noticeable, especially in insufficient understanding of division, of fractions, and of the metric system. It is therefore to be recommended that these points should be covered properly, preferably from the beginning, and more graphically.”[lxxiv] There was not a lot of theory behind this. People especially wanted to use a more concrete method because observation was considered better for stimulating the understanding of the pupils than a purely theoretical form of education. From the tone of the inspection reports it can be inferred that an observation based method was not prevalent always and everywhere: “The school runs quite regularly. The courses are given carefully and following a method. Nevertheless, it is often necessary to monitor the native moniteurs closely. These, in fact, easily forget to use the method during their lessons which was taught to them and of which they are continually reminded by the Brother Headmaster.“[lxxv] Hulstaert also noted that elsewhere. In Bamanya the principle was, according to him, used correctly in the teaching of agriculture. For example, the use of native fertiliser could be demonstrated well in the experimental gardens: “However, it would really be useful if the boys could try some real tests in the direction of improving cultivation. It must also be ensured that the boys learn to save seed for the next planting season; that is a point of educational value.[lxxvi]

He also thought that giving concrete examples in other subjects should be taken up. Practical applicability was used strongly as a criterion: “For the lessons in hygiene, the same method could be further developed, so the value would be increased. Br. Florent, for example, would certainly like to do that. In lessons about mosquitoes, for example, useful tests could be done; you could add: tracking down breeding grounds, pest control and so forth. In Bamanya this will also be useful from a practical point of view.”[lxxvii] He repeatedly hammered the point home of the necessity of more ‘illustration’: “It is further to be expected that especially the boys in the lower classes should get more graphical education in arithmetic. There should in fact be no calculation at all done without everybody doing it using their fingers or having objects before their eyes. The same goes for the metric system.”[lxxviii] Later he broadened his argument to all the teaching material: “For all subjects the illustrative method could in fact be used more. The pupils could be interested in this. And with a people that are strongly under the influence of superstition that is doubly useful.”[lxxix]

In 1941 he further defined what he meant exactly by that. The director of the school in Flandria had said the level of lower classes was too low because of the lack of preparation by the teachers. Hulstaert agreed with that and advocated better preparation in general. He also saw another means for improving performance: “If it does not improve in spite of that, then other causes must be sought and it must be considered whether the initial education needs to be better adapted. I think that, in this sense, particularly your school needs to work on modern methods used in Europe: globality, concreteness, better adaptation to the intuitive nature of your pupils, and so on. Sister Imberta should know about these work methods and it would be good if she could look in that direction.”[lxxx] A couple of years earlier he said something similar about the school in Flandria: “They give a lot of time to singing, games handicrafts, etc. that are attractive to the children yet still educational.”[lxxxi] These pronouncements seem at first sight to contradict the attitude of Hulstaert as it was described earlier. What he called ‘modern methods’ were the elements of the New School movement (the global reading method, for example) that could fit into his indigenistic point of view. It is probably not a coincidence that he used these terms in a letter that, according to Vinck, was written at the time that he became aware of certain educational studies. Apart from this it also shows that Hulstaert in his function of inspector thought that methods used in class were not concrete enough.

In the kindergartens of the vicariate the Sisters already worked regularly according to ‘modern’ principles. According to Hulstaert they used the Fröbel method in Flandria, but it is difficult to discover what that consisted of exactly: “A lot of attention, sense, observation exercises, etc. were done. A little in primary education, too. This last is kept to a strict minimum and is used only insofar as it helps the Fröbel education method.” In the same report Hulstaert also made a number of suggestions, which implies that these things had not been done previously. In âprticular, he quite strongly emphasised the use of native games, songs and verses.[lxxxii] Elsewhere there was talk of a Montessori school: it was mentioned incidentally in an article about the mission post of Mondombe. Again, here it was a Sister, Imelda, who was leading the educational project. The only other thing that was said about the school was that the children did a dance in good order and discipline for the Father who was visiting the village.

3.2. Visual material

The administration also stimulated schools to use visual material. In 1940 a competition was set up for designing wall posters, in the context of the lessons on hygiene. The purpose was to develop two series of wall posters on the basis of which lessons could be given, with the cooperation of the teaching staff everywhere in the colony. The first series should illustrate ‘cleanliness’ in its differing facets (propreté du corps, propreté de la maison, propreté du linge, le repas familial, le village bien entretenu, …)[lxxxiii], the second series must contain information on the tsetse fly, first aid in the case of cuts and wounds and on alcoholism and abstinence.[lxxxiv] That principle was also applied again later, in the context of agriculture, which experienced a revival in the early 1950s. In the context of the policy of paysannats there was an attempt to combat the exodus from the land and agriculture was promoted again, more than ever, to the Congolese population.[lxxxv] Education played its role in this; the mission inspectors were mobilised. Moentjens recommended the propaganda material from the administration in a circular to the mission superiors. It would be useful as an educational aid in the theoretical agriculture lessons: “I have the honour of sending you, in a separate package, 6 posters intended as agricultural propaganda. These posters are published for promoting the appreciation of agriculture among the population, especially among young people currently in school, who are all too inclined to turn away from agriculture. They offer the best instructional material when discussing causeries on that subject.”[lxxxvi]

Other types of wall posters were also very sought after. Especially in the context of religious education this was a regularly used teaching tool. The Sisters in Bamanya used wall posters from Speybroeck – Bonne Presse in the 1930s for the lessons in biblical history.[lxxxvii] Hulstaert also noted it in 1939 in the inspection report of the Batswa school in Flandria: “In the same sense more use could be made of the posters in religious education. The Spanish text of the existing posters could be translated into Lonkundo.“[lxxxviii] The precise manner in which the posters were used is not apparent from the pieces in the archives.

In some inspection reports from the early 1950s there is an allusion to their use: “In addition the lesson is illustrated with a picture representing J.C. attached to the scourging post. The moniteur should have used it more and his lesson would have been even more interesting.“[lxxxix] And: “Third year: catechism lesson on the readministering of baptism. The text is well written on the board. The lesson started with an explanation of a picture representing the baptism of Jesus where the pupils had to try to recognise the various people. Afterwards we continued learning the text and its explanation.”[xc] Stéphane Boale, who was at school in the same period in Bokote, spoke in similar terms about the use of the wall pictures: “There were images for all the subjects. For example, imagine you were giving a lesson on Adam and Eve. Do not think they did not have illustrations to accompany this lesson! For everything, no matter what subject, if you were talking about anatomy, hygiene, religion. First of all, there was an intuitive lesson. Firstly one asked what could be seen and then the pupils would talk about everything they could see and the explanation of the illustrations would only follow afterwards.“[xci]

Sometimes the use of more ‘visual’ methods came from material necessity. In this way the mission inspector advised the reading lessons to be written on the board in extenso in the girls’ school in Flandria because there were not enough reading books to let everyone follow at the same time.[xcii] That this in its turn would give rise to memory work had been mentioned earlier. However, it could be done differently. In the same school, inspector Moentjens praised the reading methods of the teacher a few years later: “1st year Lonkundo reading lesson: this is written on the board and always is explained well first, that is to say, the teacher asks the pupils for the meaning, explains it further and shows the application of every word in one or several sentences. This seems to me to be a very good method of education. Finally the reading on the board is taken up.”[xciii]

In a number of cases teachers went a step further in this illustrative aspect. At the boys’ school in Bamanya bible scenes were played out during religion lessons from 1937 onwards. Probably they were a sort of tableaux vivants, in which the moniteur played a role as well. Hulstaert thought that a very positive development: “They not only go down very well with the pupils; but make it possible to get more into the studied subject better and improve their way of expressing their feelings (sic), which we try hard to make more dignified while preserving their character of natural native. These attempts are done in all classes but they are the most advanced in the lower class under the direction of the moniteur BOMPOSO Antoine.”[xciv] In a number of schools this was in fact carried out outside the actual hours of lessons. In time they began to put on real plays. These performances almost always had a religious content and were frequently commentated on in the publications of the MSC. After all, they were excellent proof of what could be achieved with young Congolese. At the same time the missionaries wanted to show in this way that they had respect for the local culture.

Contents of the lessons

4.1. Examples

Finding an example of concrete lesson content is not straightforward. The inspection reports do describe the performance and attitude of the teachers and sometimes also the names of the topics dealt with but the way in which the teaching material was put across was seldom put on paper. Highly exceptional, in that context, are a few example lessons, which can be found in the Aequatoria Archive. These are only two short notes written in 1936 by Petrus Vertenten. They were almost certainly used by the moniteurs, probably for a few years. Hulstaert succeeded Vertenten as inspector and he referred to the use of the term “décimes” for a tenth of a Franc in a report. This term was, in the context of units of currency, rather unusual but Vertenten did use it in the example lesson shown here. Therefore, it is probable that this example lesson was actually used in the class. Whether the rigorous work methods, which Vertenten described, were applied to the same extent is more difficult to discover. Hulstaert made no comments on Vertenten’s methods. That is unsurprising, for these example lessons started from a concrete situation and it was a school example of learning by repetition.[xcv] Starting with a concrete question (“how much is seven times five centimes?”), an explanation was given of how the franc was divided up (the concepts “centime” – one-hundredth of a franc – and “décime” – one tenth of a franc), which differed from the division the Congolese used. The notation was explained in detail. The operations ‘division’ and ‘multiplication’ were illustrated, coupled to each other, and this in both directions.