Where Did Vladimir Putin’s Dream Of A ‘Russian World’ Come From?

Source: Independent Media Institute

04-15-2024 ~ Russian President Vladimir Putin justified the 2022 invasion of Ukraine by asserting the existence of a singular “Russian world” that needs protection and reunification. He set aside the secular socialist ideological rationales that the Soviet Union used to justify its expansion favoring the Tsarist Russia, rooted in religion and culture. But the history of political orders in the northern European forest zone, which stretches back 1,200 years, is not one of a unified Russian world.

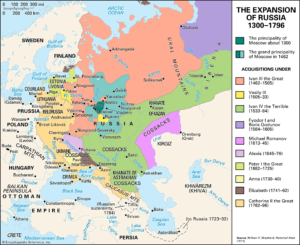

Instead, there were a series of competing orders with rival power centers in Kyiv, Vilnius, and Moscow as well as powerful nomadic steppe polities like those of the Khazar Khaganate, the Mongol Golden Horde, and the Crimean Khanate to the south. Only at the end of the 18th century would they all be forcibly annexed into a single state by Tsarist Russia’s Romanov dynasty. That unified state continued under its Soviet Union successor until it dissolved into 12 independent countries in 1991.

Ukraine and Lithuania in particular had been the centers of their own imperial polities with histories older than Russia itself and were instrumental in creating the Russian culture Putin is now so keen on defending. They achieved this in ways that did not require the protection of an autocrat.

Empires in The Forest Zone

The forest zone spanning the Dniester River in the west and the Volga River in the east historically constituted a vast (more than 2 million square kilometers) but sparsely populated region. It would become the home of three long-lived empires: Kievan Rus’ (862-1242), the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1251-1795), and the Grand Duchy (later Tsardom) of Muscovy (1283-1721). The surplus wealth that supported these empires came from international transit trade and the export of high-value furs, wax, honey, and slaves, often supplemented by raiding. After expanding beyond its forest zone home, Tsarist Russia declared itself the Russian Empire in 1721 during the reign of Peter the Great (1682-1725), but it took the rest of the century for it to gain control over its neighbors to the south and west, which was achieved during the reign of Catherine the Great (1762-1796).

States of any kind, let alone empires, were absent from the northern forest zone before the 9th century because it was then inhabited only by small and dispersed communities with little urbanization or political centralization. Engaged in subsistence farming, foraging, hunting, and animal husbandry, these communities interacted only with others like themselves or with foreign traders using its rivers to pass through the region. Dense forests and extensive marshlands presented serious obstacles to potential invaders, which were already few because the region had no precious metals to plunder or towns to occupy. This changed when the forest zone was drawn into the high-value commercial network that exchanged a flood of silver coins for furs and slaves, which were traded through a series of intermediaries. The demand for these goods and the silver to pay for them lay in the lands of the distant Islamic Caliphate and the Byzantine Empire, but it was the nomadic Khazar Khaganate (650-850), rulers of the entire steppe zone to the south, who dominated the trade routes. The Khazars exploited that position by projecting their power north into the forest zone where they imposed tribute payments in furs or silver on the communities residing there, creating a class of wealthy local leaders living in towns who were responsible for collecting the payments. They also established trading emporiums on the Volga River that attracted foreign merchants who paid a 10 percent transit tax on the goods they took in or out of the Khazar territory.

Kievan Rus’

The flow of silver resulting from the fur trade attracted the attention of Scandinavian maritime merchant/warrior groups known as the Varangians or Rus’, whose shallow draft boats were easily portaged from one watershed to another. Initially seeking only local trading opportunities, they established their political authority in the north but soon expanded southward through the Dnieper and Volga river systems to reach the Black and Caspian seas where they engaged in raiding and trading. The Varangians replaced the Khazars as the dominant power in the forest region in the 860s. By the 880s, they had moved their center south to Kyiv where they established an empire, Kievan Rus’, which encompassed 2 million square kilometers by the early 11th century. It was an empire that lasted almost four centuries and ended only after the Mongols conquered the entire region and destroyed Kyiv in 1240.

Although Kievan Rus’ is seen as the foundation of later Russian culture, it did not assume its classic form until a century and a half after it was established when Vladimir the Great (r. 980-1015), a pagan polytheist, converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity in 988 and made it the state religion after marrying a Byzantine princess. He was also responsible for turning Kyiv into a true city with a population of around 40,000 people, erecting Byzantine-style churches there and supporting trade. It was a multiethnic state that developed its own common culture by drawing on a variety of sources. Eastern Orthodox Christianity brought with it a tradition of literacy and the Cyrillic alphabet, a hierarchical clerical establishment, and a Byzantine tradition of governance where state authority was based on laws and institutions. Rus’ rulers also respected the authority of existing Slavic political institutions at the local level that included decision-making councils in towns and regions (veche), Indigenous local rulers (kniaz), and a class of aristocratic military commanders (voevoda). Although only the direct descendants of the Rus’ founder Rurik could hold the top position of the grand prince and other high ranks, this ruling lineage intermarried with its Slavic subjects (Vladimir’s mother was one of the offsprings of this kind of intermarriage), and eventually adopted their language.

Perhaps most significantly, Kievan grand princes did not wield absolute power. After the empire reached its zenith under Vladimir and his son Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1016–1054), constant wars of succession among the Rurikid elite weakened the central government to such an extent that by the mid-12th century it had devolved into a looser federation of autonomous regional polities (with Kyiv, Novgorod, and Suzdalia being the most prominent) whose leaders agreed among themselves on who would become the grand prince. The government survived because it was a jellyfish-like state that absorbed enough resources to sustain itself without requiring either a strong imperial center or autocratic leadership, and where no single part was critical to the survival of the whole.

Lacking a brain, jellyfish depend on a distributed neural network composed of integrated nodes that together create a highly responsive nervous system. As a result, jellyfish can survive the loss of body parts and regenerate them quickly. Similarly, Kiev and its grand prince was only the biggest node in a system of nodes rather than an exclusive one. And because jellyfish regeneration is designed to restore damaged symmetry rather than simply replace the lost parts, a jellyfish cut in half becomes two new jellyfish as each half regenerates what is missing. Following this pattern as well, two rival empires eventually emerged in the lands of the old Kievan Rus’ after the Mongol occupation finally ended: the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in the west and the Grand Duchy of Muscovy in the east.

The Mongol Yoke

The Mongol invasion of central Europe ended in 1242 when they withdrew their troops, never to return, but the Mongol Golden Horde retained control of the Kievan Rus’ territories. To administer the forest zone region, the steppe nomads turned to the very Rurikid elite they had come close to annihilating a few years earlier.

However fraught and unequal the relationship between the Golden Horde and its Russian clients might have been, it produced a durable governmental structure that lasted almost two and half centuries. The Mongol administration was far more intrusive and state-centered than that of the Kievan Rus’. The Horde’s demands for tax revenue and troops were high and achieved through a wide-ranging set of sophisticated administrative structures, tax systems, and censuses. As much as they may have resented the Mongols, the Rurikid rulers they appointed became richer and more sophisticated state builders in their own territories. Their endemic succession disputes were now resolved by the Horde’s Great Khan rather than on the battlefield. Although the Horde’s pagan leaders eventually converted to Islam, they maintained the Mongol Empire’s longstanding policy of religious tolerance. This included tax exemptions for all clerics and property owned by religious groups, a policy that won the Golden Horde support from the Orthodox Christian Church.

Dueling Duchies

The Horde displayed a stronger interest in controlling its eastern Russian principalities (Tver, Vladimir, Muscovy, and Suzdal) in the Volga River watershed rather than its western ones (Kyiv, and Smolensk) in the Dnieper River watershed. This was because the east was now more populous (1,350,000 people) than the west (800,000 people) and more easily controlled from the Horde’s capital of Sarai on the lower Volga. As Mongol interest in the western forest zone receded, the Lithuanians moved in to reorganize it. With their capital in Vilnius, the Lithuanians had avoided the initial Mongol onslaught and began expanding south into the Dnieper region during the early 14th century to create the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL), the largest empire in all of medieval Europe.

What was so striking about the emergence of the GDL and the territories it occupied was how closely the Lithuanians followed the pattern of the Rus’ as foreigners moving into a power vacuum produced by the decline of a steppe nomadic power and how they superimposed themselves on an existing political system too fractured to unite from within. The economy improved as the region became more stable within an imperial “Pax Lituanica” that provided security for merchants moving their goods along the strategic international trade networks. The minority pagan and Catholic Lithuanians disturbed the existing order as little as possible. They allowed the Russian nobility to retain both, their privileges and the Eastern Orthodox faith. They created a cohesive upper class that transcended simplistic definitions of ethnic boundaries. Like the Kievan Rus’, the GDL was a jellyfish polity that lacked a true metropole. It integrated many different nodes of production and authority into a single political system, expanding and contracting without changing the structure of the polity. The GDL became the dominant power in the forest zone for a short period after Tamerlane destroyed the Golden Horde’s capital of Sarai in 1395.

The Grand Duchy of Muscovy arose to challenge the GDL after Ivan III, also known as Ivan the Great, (r. 1462-1505) united the northeastern Russian principalities and declared his independence from the nomad Great Horde in 1476. His grandson, Ivan IV or Ivan the Terrible, (r. 1547-1584) proclaimed Russia a tsardom and coronated himself as its first tsar. It was a bid for a new imperial status that sought parity with the Horde—descendants of Genghis Khan who had formerly ruled Russia—the Ottoman sultan, and Europe’s Holy Roman Emperor. Within Russia, the tsar’s position uneasily combined the paternalism of a Byzantine emperor responsible for the protection of the Eastern Orthodox faith and its believers with the raw power of a Mongol Khan who ruled an absolutist and secular state. In a series of wars during the 1550s, Ivan the Terrible conquered the steppe regions of Kazan and Astrakhan along the Volga down to the Caspian Sea and took control of a number of Baltic ports. As a direct dynastic successor of its founder Rurik, Ivan then insisted that the Poles and Lithuanians return the lands of the Kievan Rus’ to him.

It was not to be. Ivan’s destructive domestic policies during the next 10 years weakened Russia and his enemies invaded it. Moscow was burned to the ground during a cavalry raid led by the Crimean Khan in 1571. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s newly elected king, the Hungarian Stephen Báthory, went to war with Ivan in 1578 to reclaim the GDL’s disputed territory. Báthory forced Russia to abandon the Baltic ports and cede Pskov to the Poles in a 1582 peace agreement signed a few years before Ivan’s death. After Ivan’s son Tsar Dmitri died without an heir in 1598 (ending the Rurikid dynasty that had lasted for more than 700 years), Russia entered its Time of Troubles turmoil where its very existence as a sovereign state was threatened. That period of anarchy ended only with the emergence of a new Romanov dynasty of tsars in 1613 who helped restore political stability and went on to rule Russia for the next 300 years. However, it would take another century for Russia to again move north to the Baltic Sea under Peter the Great, and then west and south into Ukraine and Crimea under Catherine the Great. Their success made the Russian Empire the world’s largest by area. It collapsed in 1917 during World War I, but most of its old territories remained part of the new USSR.

The Legacy of Empire

Russia emerged as the Soviet Union’s most powerful successor state after it collapsed in 1991 (Map 7). Although shorn of about 5.5 million square kilometers of former Soviet territory, Russia remained the world’s largest country with 17.1 million square kilometers. Its status as a peer polity with the U.S., the EU, and China rested on its possession of the Soviet Union’s nuclear arsenal and robust spending on conventional military forces that amounted to around 3 or 4 percent of its GDP from 2010 to 2020. But in other respects, Russia was not in their league. In 2020, the Russian economy comprised only 1.79 percent of the world’s total GDP, more than an order of magnitude smaller than the U.S. (24.8 percent), China, (18.2 percent), or the EU (17 percent). Indeed, its GDP was smaller than South Korea’s, a country that is less than 100,000 square kilometers in size, whose top exports were advanced electronics, machinery, and motor vehicles. Russia’s main exports were oil, natural gas, coal, timber, minerals, and metals. While the Soviet Union’s population was larger than that of the U.S. when it dissolved, Russia’s population of 146 million in 2020 was less than half that of the United States and was shrinking rather than growing.

Its neighbors, Ukraine and the Baltic states returned to their roots, too. With political structures that rejected autocracy and saw their future tied to Europe, Ukraine and the Baltic states restored modes of governance and alliances that were the norm before their incorporation into Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union. Those of their people who defined themselves as culturally Russian saw no need to be political subjects of Russia to maintain their language and traditions that had long thrived without the need for an autocrat to watch over them.

Putin’s post-Soviet Russia is a nuclear-armed Muscovy with frontiers that would have been familiar to Ivan the Terrible. Its mere survival was an impressive feat—most other places would have experienced a cascade of further breakups as seen in the case of the former Yugoslavia—but Russia retained its resilient jellyfish structure. It could reconstitute itself from whatever damaged parts survived, albeit on a smaller scale. Russia moved forward rather than dying, although it failed to realize the Baltics and Ukraine could do the same without it. Despite 70 years as part of a centralized Soviet command economy, Russia remained a network of economic and political nodes where no single part was critical to the survival of the whole. Departing from the Soviet Union’s closed economy that aimed at self-sufficiency in all economic sectors, Russia returned to a Muscovite (and even Rus’) pattern of exporting its natural resources to the world economy to sustain itself. It was these exports that financed the high military spending required to maintain itself as a peer player with other world powers and pay for the welfare services that were now expected by its citizens.

Despite Putin’s intent to restore Russia’s status as a world imperial power, his was a far less cosmopolitan polity than either Tsarist Russia or the Soviet Union and is apparently happy to be so. Russia now defined itself in nationalist terms that stressed deep historical ties to a Russian cultural past and ignored the existence of the other empires that had ruled the region except to claim they were Russian when convenient.

Putin raised the status of the Orthodox Church and portrayed himself as the defender of its traditional Russian cultural values—the absolutist Tsar-equivalent protecting a Holy Russia from the evils of the outside world. Putin justified his invasion of Ukraine in 2022 as an act of domestic house cleaning by defining the Ukrainians as a variety of wayward Russians—sheep who had strayed and were now being brought back into the fold, not people who had their own independent states and empires when Russia was still being ruled by the Mongols.

And that Mongol legacy runs deep. The many photographs of a bare-chested Putin engaging in horseback riding, hunting, and plunging into icy waters channeled the Great Khan tradition of the steppe whose rulers felt it was necessary to demonstrate their physical vitality because state power was invested in a living person rather than a governing institution. Similarly, Putin made the continued possession of great wealth dependent on personal loyalty to him—creating a patrimonial system resembling that of the Tsars and their boyars rather than a modern capitalist economy.

Many talented Russians are choosing to make their mark abroad under these circumstances, forfeiting Russia’s opportunity to remain on the technological cutting edge that China and the United States had seen as the economic battleground of the future. But Russia has not felt the need to compete in these areas to remain relevant so long as it can wield military power backed by nuclear weapons.

What could undermine Russia’s ability to act as a peer polity now and in the future are two related things that have resulted from its invasion of Ukraine. In the short term, isolation from the world economy in response to its invasion of Ukraine threatens to choke off the export of raw materials that make up the bulk of its revenue. In the longer term, the instability Russia has created in the oil and gas market hastens the emergence of carbon-free wind, geothermal, solar, and nuclear energy technologies that will leave its oil and gas resources stranded without buyers. Empires that depended on regular flows of outside revenue to finance themselves, whatever way they obtained them, rarely survived once those external revenue sources disappeared.

Vladimir Putin sees himself as another Peter the Great, but the better analogy is to Ivan the Terrible. Ivan’s absolute autocratic power, refusal to take advice, and paranoia combined with persecutions at home and wars abroad produced a powerful state that was on the verge of collapse by the end of his reign. Russian history proclaimed three rulers “the Great,” but Putin is less likely to join their ranks and, instead, is more likely to become the country’s second “the Terrible.”

By Thomas J. Barfield

Thomas J. Barfield – Boston University

Author Bio: Thomas J. Barfield is professor of anthropology at Boston University. His new book, Shadow Empires, explores how distinctly different types of empires arose and sustained themselves as the dominant polities of Eurasia and North Africa for 2,500 years before disappearing in the 20th century. He is a renowned historian of Central Eurasia and the author of The Central Asian Arabs of Afghanistan, The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, 221 BC to AD 1757, Afghanistan: An Atlas of Indigenous Domestic Architecture, and Afghanistan: A Cultural and Political History (revised and expanded second edition 2022, Princeton University Press).

Source: Human Bridges

Credit Line: This article is distributed by Human Bridges, first published in the Sentinel Post.