ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ Negotiation Versus Deliberation

Abstract: Negotiation and deliberation are two context types widely studied in the argumentation literature. However, one issue that still must be addressed is how to distinguish negotiation and deliberation in practice. In this paper, I seek to develop linguistic criteria to identify instances of these genres in discourse. To this end, I characterise the felicity conditions of the superordinate speech acts defining and structuring deliberation and negotiation encounters.

Keywords: Deliberation, negotiation, offer, proposal, superordinate speech act.

1. Introduction

Most contemporary argumentation theorists agree that fallacy judgments are, ultimately, context-dependent. Accordingly, over the last two decades we have witnessed a wave of attempts to characterise different types of contexts and formulate specific reasonableness conditions for the use of argumentation within each of them. Among these attempts, those carried out by Walton and the pragma-dialectical school are probably among the most systematic and advanced.

In Walton’s (1998) approach, context types are conceptualised as ‘dialogue types’: i.e., as exchanges of speech acts between two speech partners governed by a primary goal and a set of rules. Within the pragma-dialectical framework (Van Eemeren, 2010), context types are partly studied through the concept of ‘discourse genres’, conceived as “socially ratified ways of using language in connection with a particular type of social activity” (Fairclough, 1995, p.14).

‘Negotiation’ and ‘deliberation’ are two among a number of other context types that have been studied by these authors. Walton and Krabbe (1995) have proposed a characterisation based, mainly, on their primary goals and rules; pragma-dialecticians have characterised the two contexts in terms of their communicative conventions and the constraining force of those conventions on argumentative discourse. Thanks to these descriptions, it has become possible to carry out context-sensitive and, thereby, more nuanced evaluations of argumentative discussions.

However, one issue that still must be addressed by the aforementioned contextual approaches to argumentation is how to distinguish negotiation and deliberation in practice. Since negotiation and deliberation share important features – both are collective decision-making procedures centred on the practical question ‘what to do’ – they can be easily confused during the process of analysing actual fragments of discourse. This difficulty is compounded by the fact that it has not yet been made clear which of the rules or conventions specified for each genre are – to use a well-known distinction – ‘constitutive’ and which are only ‘regulative’ of these practices (Rawls, 1955; Searle, 1969). Constitutive rules or conventions not only regulate, but also define the activity they regulate. Thus, constitutive rules or conventions are reliable criteria to distinguish one genre from another. Regulative rules or conventions, by contrast, only regulate a pre-existing activity and are, for this reason, unreliable criteria. If, for example, one of the parties violates a regulative convention of the genre of deliberation, it does not necessarily mean that the parties are not deliberating. It may just means that one party is behaving fallaciously.

With a view to contributing to the study of argumentation in context, this paper seeks to develop criteria that can help the analyst distinguish negotiation and deliberative practices. In this endeavour, I will use pragma-dialectics as my main theoretical starting point.

2. Discourse genres and superordinate speech acts

In line with the rational approach to discourse underlying the pragma-dialectical theory (Eemeren et al., 1993), this essay studies the genres of negotiation and deliberation as rational (i.e. goal-oriented) and socially ratified sequences of speech acts, motivated by the need to repair a specific kind of interactional problem in a given social activity.

To develop criteria for establishing whether or not a particular sequence is an instance of negotiation or deliberation, I shall make use of the concepts of ‘superordinate speech act’, ‘pre-sequence’ and ‘post-sequence’ developed in the field of conversational analysis. A superordinate speech act is a speech act that pragmatically organises a sequence by structuring the interaction and aiding in the interpretation of the speech acts performed before and after the superordinate speech act. Pre-sequences and post-sequences are sequential expansions occurring before and after a superordinate act (Jacobs & Jackson, 1980, 1983).

The hypothesis I wish to explore in this paper is whether there is a specific superordinate speech act within each genre sequence, the performance of which can be seen as a prima facie indication that the sequence is a token of one genre rather than the other. Since, according to this hypothesis, the performance of a certain type of speech act defines the genre in which the discourse unfolds, the requirement to perform such speech act can be considered a constitutive convention of the genre if the hypothesis is proved to be correct.

In exploring this hypothesis I will assume that any pre and post-sequences which are relevant to deciding on the meaning or acceptance of the superordinate speech act – in other words, whose performance is instrumental to determining whether the felicity conditions of the superordinate speech act hold – will fall within the scope of the same instance of negotiation or deliberation.

3. The superordinate speech act of negotiation

Since the late 1960’s, there has been a number of efforts – particularly in the field of business communication and artificial intelligence – to describe negotiations and deliberations from a speech act perspective. Some of these efforts have been directed at identifying the types of speech acts that are vital to the negotiation and deliberation process. In terms of negotiation, scholars generally agree that commissives and, particularly, offers are essential to any negotiation activity (e.g., Tutzauer, 1992, p. 67; Fisher, 1983, p. 159). This suggests that offers are likely to be the superordinate speech act underlying negotiation.[i]

An offer counts as an attempt by the speaker to commit himself to perform a future action if this is accepted by the hearer. Offers are similar to promises, but they differ from promises in that the commitment to perform the future course of action is always conditional on the hearer’s acceptance. Put differently, while offers become binding only on acceptance, promises become binding as soon as they are performed (Searle & Vanderveken, 1985, p. 196). Offers and promises also differ, to some extent, in the psychological state expressed by the speaker concerning the preferences of the audience. When a speaker issues a promise, he can be committed to the view that he believes – rightly or wrongly – that the hearer would like him to perform the action. But when an offer is made, speakers can only be committed to the view that they suppose, conjecture or guess that such is the case. Offers seem to be more tentative than promises.

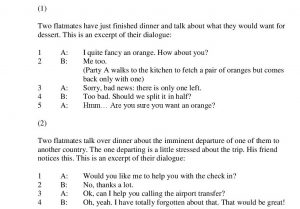

Not all types of offers, however, seem to be well-suited to performing the role of negotiation’s superordinate speech act. To demonstrate this, compare the dialogues in examples 1 and 2:

Not all types of offers, however, seem to be well-suited to performing the role of negotiation’s superordinate speech act. To demonstrate this, compare the dialogues in examples 1 and 2:

Are both examples instances of negotiation? The answer appears to be in the negative. Only Example 1 seems to match our pragmatic intuitions about what a negotiation is. However, in both examples, at least one offer is performed. In Example 1, turn 4, party B offers to split the orange in half; in Example 2, turns 1 and 3, party A offers his help to party B in order to alleviate the stress of his trip.

If in both dialogues an offer is being performed, why, then, is Example 1 perceived as a negotiation encounter, while Example 2 is perceived as a token of something else? The explanation lies, I think, on the type of offer performed in each case. In Example 1, the offer is performed in an attempt to reconcile a trivial conflict of interest. Judging by the expressions of disappointment in turns 3 and 4, both parties want the whole orange for themselves, and this creates a tension between them as there is only one orange left. In Example 2, there are no signs of a conflict of interest, at least not on the basis of the information available. On the contrary, their interests appear to be identical, as they both want party B to feel less stressed about the upcoming trip. In order to distinguish the two types of offer, I shall refer to the type of speech act performed in Example 1 as the speech act of ‘making an offer’ and to the type of speech act performed in Example 2 as a ‘generic offer’.

Accordingly, not all types of offers can be analysed as the superordinate speech act of negotiation; only the speech act of making an offer fulfils this role. Like every type of offer, making an offer counts as an attempt by the speaker to commit himself to perform an action, so long as the action is accepted by the hearer. However, unlike generic offers, such a commitment is taken by the speaker with the specific objective of reconciling a presumed conflict of interest with the listener. The conflict of interest presumed by the speaker may become clear while the dialogue unfolds – as illustrated in Example 1 – or be presupposed by the context and never verbalised by either party, as often happens in market exchanges.

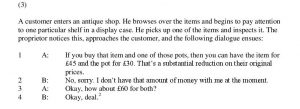

Speakers can of course make an offer in non-conditional or conditional terms. To make a conditional offer counts as a commitment by the speaker to perform some future action, on condition that the hearer performs another action in turn (besides the action of accepting the speaker’s offer). Example 3 below contains only conditional offers and is also a clear cut example of a negotiation encounter:

Speakers can of course make an offer in non-conditional or conditional terms. To make a conditional offer counts as a commitment by the speaker to perform some future action, on condition that the hearer performs another action in turn (besides the action of accepting the speaker’s offer). Example 3 below contains only conditional offers and is also a clear cut example of a negotiation encounter:

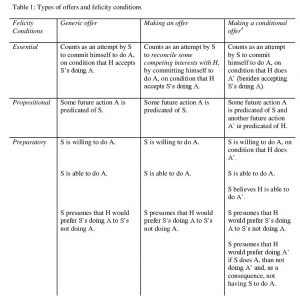

In order to distinguish the three types of offers discussed, I compare them in table 1 in terms of their felicity conditions: [ii]

An illustration

Thus far I have argued that making an offer (non-conditional or conditional) is the superordinate speech act of negotiation and that the performance of this speech act can be used as a criterion to determine whether or not a negotiation has taken place. I will now illustrate how the criterion can be applied in practice. The example of negotiation under analysis has been taken from Fisher, Ury and Paton (1991 [1981], p. 23). In contrast to the examples already analysed, Example 4 not only involves a process of ‘distributive’, but also ‘integrative’ negotiation.

According to Walton and McKersie (1992), distributive negotiation occurs when the parties assume that what is at stake is the distribution of a fixed pie. In this case, the gains of one party necessarily result in the losses of the other. Distributive negotiations result in zero-sum solutions. Dividing the orange between two parties is a paradigmatic case of distributive bargaining: the more sections of orange one party gets, the less the other. By contrast, integrative negotiations take place when the parties no longer assume that what is at stake is the distribution of a fixed pie, but instead search for a solution where both can maximize their gains simultaneously.  Integrative negotiations aim at a win-win solution.

Integrative negotiations aim at a win-win solution.

Since Example 4 involves both types of negotiations, it will also help me demonstrate that the proposed criterion is also useful in identifying integrative negotiations:

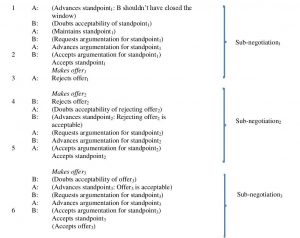

The sequence of speech acts used by the parties in each turn is represented below. The superordinate speech acts underlying the verbal exchange are in italics; implicit and projected speech acts appear between parentheses:

1 A: (Advances standpoint1: B shouldn’t have closed the

1 A: (Advances standpoint1: B shouldn’t have closed the

window)

B: (Doubts acceptability of standpoint1)

A: (Maintains standpoint1)

B: (Requests argumentation for standpoint1)

A: Advances argumentation for standpoint1

2 B: (Accepts argumentation for standpoint1)

Accepts standpoint1

Makes offer1

3 A: Rejects offer1

Makes offer2

4 B: Rejects offer2

A: (Doubts acceptability of rejecting offer2)

B: (Advances standpoint2: Rejecting offer2 is

acceptable)

A: (Requests argumentation for standpoint2)

B: Advances argumentation for standpoint2

5 A: (Accepts argumentation for standpoint2)

Accepts standpoint2

Makes offer3

B: (Doubts acceptability of offer3)

A: (Advances standpoint3: Offer3 is acceptable)

B: (Requests argumentation for standpoint3)

A: Advances argumentation for standpoint3

6 B: (Accepts argumentation for standpoint3)

Accepts standpoint3

(Accepts offer3)

The analysis proposed shows that the superordinate speech act of making an offer is performed three times in the dialogue: in turns 2, 3 and 5. Thus, according to the identification criterion proposed, there are three negotiation processes in this fragment.

The sequence of speech acts involved in such processes is indicated in the analysis between braces. We can clearly identify these three negotiation sequences because each of them is relevant in determining the meaning or the acceptability of their respective superordinate speech act. For example, in the first negotiation process, the pre-sequence of speech acts performed (and projected) in turn 1 is relevant to the offer made in turn 2: party A’s performance of those speech acts is necessary to establish the existence of a conflict of interest with party B. If such conflict had not been established, then the speech act performed by party B in turn 2 would not be that of making an offer – but only a generic offer.

Likewise, the post-sequence of argumentatively relevant speech acts performed (and projected) in turn 4 (and partly in 5) is necessary to decide on the acceptability of the offer that was made in turn 3. It is clear however that despite there being three processes of negotiation, all of them can be seen as part of a broader negotiation framework because they are all an attempt at reconciling the same interactional problem: what should the parties do with the window in the library, considering that one prefers it open and the other one would rather have it closed. In this sense, the three processes can be reconstructed as sub-negotiation processes.

On the basis of the analysis presented, we can also show that our criterion applies to both types of negotiations. Sub-negotiations 1 and 2 are clearly distributive negotiations; sub-negotiation 3 is a classic example of integrative negotiation. However, in both cases, there is a conflict of interest between the parties and, in both cases too, the offer performed is a clear attempt at dealing with the conflict. In sub-negotiation 1, the offer made is an attempt at reconciling the fact that party A wants the window open while party B wants it closed; in sub-negotiation 2, the offer is a reaction to the fact that party A doesn’t want to leave the window open a crack and party B wants to leave it open a crack; in sub-negotiation 3, the offer is an attempt at reconciling the fact that party A wants the window halfway and party B does not. The difference between the two types of negotiations is not, therefore, that in one case an offer is made while in the other a different type of speech act is performed. In both types of negotiations, the speaker makes an offer. The difference lies in the way in which the speaker attempts to solve the conflict of interest in each case by making an offer. In a distributive negotiation, the offer is made in order to solve a conflict between interests X and Y by trying to reach a compromise somewhere between interests X and Y. In an integrative negotiation, the offer is performed to solve a conflict between interests X and Y by trying to fulfil the parties’ convergent interests, which are neither shared nor in conflict, X’ and Y’ (in this case, party A’s interest to have more air in the room and party B’s interest in avoiding a draft cold coming in).

4. The superordinate speech act of deliberation

Several authors have studied the role of proposals within the deliberative genre (e.g., Kauffeld, 1998; Aakhus, 2005; Walton, 2006; Hitchcock et al, 2007). Walton’s view on this issue is particularly relevant here. According to Walton (2006, p. 181), the activities of proposing and deliberating are intrinsically related to one another. This idea is expressed in the way he defines the goal of deliberation, namely, as that of deciding “which is the best available course of action among the set of proposals that has been offered” (my italics). By means of this definition, Walton suggests that the very existence of a deliberative encounter is logically dependent on the (explicit or implicit) performance of the speech act of proposing and thereby implies that proposals are deliberation’s superordinate speech act. This is not to say, of course, that the performance of the speech act of proposing is sufficient to establish the deliberative nature of some discursive interaction; the performance of a proposal is only a necessary condition. Deliberation is also defined by the presence of the speech act of argumentation.

If proposals are the superordinate speech act of deliberation, then the distinction between negotiation and deliberation boils down to the distinction between the speech act of making an offer and the speech act of proposing. In order to characterise proposals and distinguish them from offers, it is first necessary to make a distinction between the English illocutionary verb ‘to propose’ and the illocutionary act or speech act of proposing.

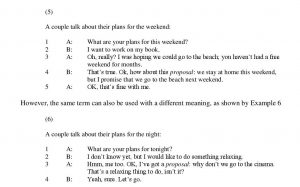

The illocutionary verb ‘to propose’ (and the related noun ‘proposal’, referring to the act of proposing) can be used at least in two ways. In one sense, it is used to refer to the speech act of making an offer, as Example 5 illustrates:

However, the same term can also be used with a different meaning, as shown by Example 6

However, the same term can also be used with a different meaning, as shown by Example 6

Both examples use the term ‘proposal’. However, I would argue that the same term is used to refer to different types of types of speech acts. It is only the second use of the term ‘proposal’ that interests me here and that I wish to capture when I henceforth speak of the speech act of proposing.

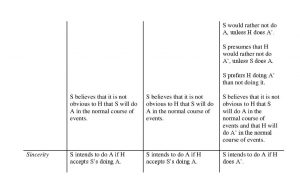

Having made the distinction between illocutionary verbs and the speech act of proposing, we are now in a position to contrast the speech acts of making an offer and that of proposing. The best way to establish their difference is by comparing their felicity conditions. The felicity conditions of proposing set out in table 2 are largely based on Aakhus (2005):[iii]

5. Differences between making an offer and proposing

An analysis of the felicity conditions of the speech act of proposing, as defined in this article, shows that there are two main differences between a proposal, on the one hand, and making a non-conditional or conditional offer, on the other.

First, when a speaker makes a proposal, the speaker predicates the same collective action of both speaker and hearer.[iv] This is specified not only in the propositional content condition of the speech act, but it is also suggested in the essential condition, as the action proposed is an action mutually brought about by speaker and hearer. This is not true when a speaker makes an offer. In order to make a non-conditional offer, it is sufficient for the speaker to predicate an action of himself, and in order to make a conditional offer it is sufficient for him to predicate an action of himself and a different action of the hearer. When making an offer, however, speakers may also predicate a collective action for both speakers and hearers.

Consider, for instance, Example 5. Party A is committing himself to two collective actions, both of which involve the hearer: both parties will stay at home this weekend and both parties will go to the beach the next. Thus, if a speaker commits himself to an action that does not involve the hearer, we can be certain that he has not performed a proposal. Yet, if the hearer commits himself to an action that also involves the hearer, it may be a proposal, but it can also be an offer. In short: to propose is necessarily to predicate a collective action of speaker and hearer; to make an offer is to predicate an action from the speaker which may or may not involve mutually bringing it about with the hearer.

The second difference between making an offer and proposing relates to whose interests are meant to be served by the action(s) that speaker (and hearer) would be carrying out. This difference becomes clear when examining the preparatory conditions of the speech acts. When a speaker makes a proposal, he is committed to the view that the action proposed will further an interest – goal, objective, etc. – that is shared by both speaker and hearer. When a speaker makes an offer – non-conditional or conditional – he is committed to the view that his action will further, in varying degrees, interests that are not shared by speaker and hearer. In the context of a distributive negotiation, the offer will attempt to partially further the differing interests of the two parties by means of a compromise. In the context of an integrative negotiation, the offer will be directed at fully furthering the parties’ convergent interests.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, I have argued that negotiation and deliberation can be distinguished in practice by examining whether or not the superordinate speech acts underlying each of these genres – making an offer and making a proposal – have been performed. I have also specified the felicity conditions of these speech acts in order to make clear their differences. Moreover, I have emphasised that for a deliberation to take place not only a proposal has to be performed, but also argumentation in favour or against that proposal.

I believe this approach suggests at least two further lines for research. First, I presume that a similar analysis can be carried out with other discourse genres, such as adjudication information-seeking and consultation, in relation the speech acts of accusing informative requests, and advising.

Second, it is possible that the occurrence of deliberation or negotiation (and other genres) depends not only on the performance of the superordinate speech acts that I have identified, but also on the specific demands imposed by the macro-context or communicative activity type in which they occur. Thus, for example, in the context of an antique market, a negotiation may consist solely of an offer and the rejection of that offer. In the context of a collective bargaining process between a trade union and a company, however, the same sequence of speech acts – an offer and a rejection of the offer – is probably an insufficient indication that a negotiation dialogue has taken place. In such a context, if one of the parties systematically rejects the offers made by the other party, and makes no counter-offers in turn, then the party who is making the offers would probably be right in accusing the other party of not being ‘open to negotiation’. Clearly, the criteria I have proposed to determine whether or not a negotiation or deliberation has taken place are minimal and may need to be complemented with the particular requirements of a given social activity.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the members of the Institute of Argumentation at the Law Faculty of University of Chile for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper.

NOTES

[i] Various authors (e.g., Sawyer & Guetzkow, 1965; Prakken & Veen, 2006; Amgoud & Vesic, 2012) have pointed out that argumentation not only can play a role, but also that its use is highly recommendable in negotiations. This does not mean, however, that the performance of argumentation is necessary for a negotiation to take place. Paradigmatic cases of distributive bargaining, for example, may not involve argumentation.

[ii] The analysis of conditional offers is based on Tiersma (1986), although he presents this set of conditions as the felicity conditions of offers in general, not of conditional offers in particular.

[iii] Differences relate to the propositional content and sincerity conditions.

[iv] An action can be collective in the sense of shaking hands and getting married – that is, the action cannot take place unless both parties engage in it –, but it can also be collective in the sense of lighting a fire – with one bringing the logs and the other fetching the matches

References:

Aakhus, M. (2005). The act and activity of proposing in deliberation, paper presented at the ALTA conference, August.

Amgoud, L. & Vesic, S. (2012). A formal analysis of the role of argumentation in negotiation dialogues. Journal of Logic and Computation, 5 (22), 957-978.

Eemeren, F. H., van (2010). Strategic maneuvering in argumentative discourse: Extending the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst, R., Jackson, S., & Jacobs, S. (1993). Reconstructing argumentative discourse. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis. London: Longman.

Fisher, R. (1983). Negotiating power, getting and using influence. The American Behavioural, 27 (2), 149-166.

Fisher, R., Ury, W. & Patton, B. (1991). Getting to yes. Negotiating agreement without giving in. (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Hitchcock, D., McBurney, P. & Parsons, S. (2007). The eightfold way of deliberation dialogue. International Journal of Intelligent Systems, 22 (1), 95-132.

Jackson, S., & Jacobs, S. (1980). Structure of conversational argument: Pragmatic bases for the enthymeme. Quaterly Journal of Speech, 66, 251-265.

Jacobs, S., & Jackson, S. (1983). Speech act structure in conversation: Rational aspects of pragmatic coherence. In R. T. Craig & K. Tracy (Eds.), Conversational Coherence: Form, Structure and Strategy (pp. 47-66). Beverly Hills: Sage.

Kauffeld, F. (1998). Presumption and the distribution of argumentative burdens in acts of proposing and accusing. Argumentation, 12 (2), 245-266.

Prakken, H. & Veenen, J. van (2006). A protocol for arguing about rejections in negotiation. In S. Parsons, N. Maudet, P. Moraitis & I. Rahwan (Eds.), Argumentation in Multi-Agent Systems (pp. 138-153). Berlin: Springer.

Rawls, J. (1955). Two concepts of rules. The Philosophical Review, 64 (1), pp. 3-32

Sawyer, J. and H. Guetzkow, 1965. Bargaining and negotiation in international relations. In H. Kelman (Ed.), International Behaviour: A Social-Psychological Analysis. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Searle, J. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Searle, J. & Vanderveken, D. (1985). Foundations of illocutionary logic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tiersma, P. (1986). The language of offer and acceptance: speech act and the question of intent. California Law Review, 74 (1), 189-232.

Tutzauer, F. (1992). The communication of offers in dyadic bargaining. In L.L. Putnam & M.E. Roloff (Eds.), Communication and Negotiation (pp. 67-82). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Walton, D. (1998). The new dialectic: Conversational contexts of argument. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Walton, D. (2006). How to make and defend a proposal in a deliberation dialogue. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 14 (3),177-239.

Walton, D. & Krabbe, E. (1995). Commitment in dialogue: Basic concepts of interpersonal reasoning. Albany: University of New York Press.

Walton, R. & McKersie, R. (1992). A behavioral theory of labor negotiations: An analysis of a social interaction system. New York: McGraw Hill.