Constantinopel: in het kamp van de vijand

De zee van Marmara vanaf het Yedikule-kasteel

In 330 gaf de Oost-Romeinse keizer Constantijn de door hem ingenomen stad Byzantium de naam Constantinopel. In 413 begon de Romeinse keizer Theodosius II met de bouw van de grote muur, die tot de dag van vandaag een verbinding vormt tussen de oevers van de Bosporus en Zee van Marmara. Vele oorlogen hebben de Byzantijnen gevoerd tegen binnendringende volkeren, vele malen ook werd Constantinopel bedreigd en vele intriges en opstanden leidden tot troonswisselingen waarbij verschillende heersers de dood vonden. Van de zevende tot de tiende eeuw werd er regelmatig strijd geleverd tegen de Arabieren die het Byzantijnse rijk binnendrongen tot in Armenië, Cappadocië, Anatolië, Cyprus en Rhodos. In 1057 kwamen de Comnenen aan de macht na een opstand van de Byzantijnse militaire bevelhebber Isaak Comnenus tegen de heersende keizer Michael. In 1076 werd het rijk geteisterd door ernstige hongersnood en de pest. In 1081 betrad Alexius Comnenus de Byzantijnse troon. Zijn vijftienjarige vrouw Irene Doukas werd gekroond tot keizerin. In datzelfde jaar werd het Byzantijnse leger door de uit Zuid-Italië afkomstige Noormannen verslagen bij Dyrrachium in het huidige Albanië. In 1085 namen de Seltsjoeken Antiochië in en werd het Byzantijnse rijk teruggedrongen tot in Klein-Azië.Parel van de Bosporus

Territories of the Byzantine empire, ca. 1081

Byzantium, Constantinopel. Het tegenwoordige Istanbul. Oude namen voor een klassieke stad. Londra Asfalti heet de grote westelijke toegangsweg tot de stad, met een naam die kennelijk wil aangeven dat ze helemaal in Londen is begonnen. Na het passeren van Istanbuls structuurloze, overhaast voor de aanstormende immigranten aangelegde satellietsteden gaat de weg dwars door de lange oude muur van Theodosius de stad binnen om daar op te gaan in het helse verkeer van de grote boulevard die vlak voor de beroemde Aya Sofia eindigt.

Het is een paar honderd meter voor de zee; tevens de laatste halte van Europa en een verzamelpunt voor toeristische activiteiten. Want Istanbul mag veel strijd hebben gekend en meer dan eens door een menselijke wervelwind zijn toegetakeld, haar tot zeven eeuwen v. Chr. teruggaande historie heeft een keur aan imposante monumenten nagelaten die zowel de kruisvaarders als de Turken overleefd hebben. De oude stad heeft de vorm van een hondenkop en wordt aan twee zijden omgeven door de wateren van de Gouden Hoorn en de Zee van Marmara, waarvan de oevers verbonden worden door de bijna zeven kilometer lange landmuur, die ondanks de invloed van de tand des tijds de stad nog steeds als een machtige barrière afsluit van de buitenwereld. Wie de kaarten van Byzantium, Constantinopel en Istanbul naast elkaar legt, ziet dat meer dan twee millennia geschiedenis de vorm en structuur van de stad onaangetast hebben gelaten. Alleen moest er voor de uitdijende bevolking plaats gezocht worden aan de overzijde van de Gouden Hoorn en in het andere werelddeel aan de overkant van de Bosporus. Hier wordt de stad Üsküdar genoemd en tussen het Aziatische bootstation Harem en het Europese Sirkeci varen dagelijks honderden overvolle passagiersschepen heen en weer om het contact met het economische hart van Turkije te onderhouden. Ooit was het treinstation van Sirkeci de laatste halte van de legendarische Oriënt Express met haar knusse schemerlampjes, notenhouten wandbetimmering en gecapitonneerde banken. Wat rest is de Balkan Expres waar vrouwen met schelle slavische stemmen en mannen in glimmende trainingspakken grote hoeveelheden bagage door de ramen van de uitgewoonde wagons naar binnen werken. Buiten het station hangt de geur van bruinkoolverbranding. Rode, knarsende trammetjes en voetpaden vol sjouwers, theeverkopers en toeristen leiden naar de nabij gelegen Sultanahmet wijk waar het moderne toerisme de plaats heeft ingenomen van de hippie hangouts die de stad als uitvalspoort naar het Oosten in de jaren zestig zo beroemd gemaakt hebben.

De keizer

‘O, wat een prachtige, edele stad! Wat een kloosters en paleizen en wat een vakmanschap! Ja, wat een schitterende straten en wijken Het zou te veel tijd nemen om de weelde van alles wat ik gezien heb – goud, zilver en allerlei kleding en heilige voorwerpen – te beschrijven,’ verzucht een opgewonden reisgenoot van Godfried wanneer hij even een kijkje binnen de muren heeft kunnen nemen.

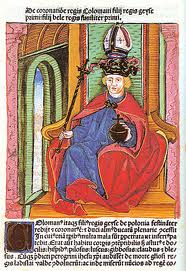

‘We mochten de stad alleen betreden in groepjes van ten hoogste vijf personen en met tussenpozen van een uur, omdat keizer Alexius bang was dat we hem kwaad zouden doen.’ Wie was Alexius Comnenus, deze veldheer die zijn keizer Nicephorus verstootte en zelf de kroon beklom? ‘Hij was geen groot man, maar wel breed geschouderd en goed gevormd’, schrijft zijn dochter Anna Comnena in haar beroemd geworden biografie over haar vader die zijn grenzeloos bewonderde. ‘Als hij recht op stond maakte hij niet direct veel indruk, maar als je hem met zijn onverbiddelijke blik in de ogen op de troon zag zitten, deed hij denken aan een wervelwind, zo overrompelend was de uitstraling van zijn persoonlijkheid. Hij had donkere, gebogen wenkbrauwen en zijn ogen waren zowel angstaanjagend als vriendelijk.’ Anna had als veertienjarige de komst van de kruisvaarders van nabij meegemaakt en had geen goed woord over voor de barbaren die ‘deden alsof ze op pelgrimage waren, maar in werkelijkheid Alexius wilden onttronen en de hoofdstad grijpen.’

Brood en spelen

Het is een winderige, kille avond. Terwijl Godfried zich voor de stadsmuren zit te verbijten, heeft Alexius zich flink te goed gedaan aan wijn, wild en gevogelte voordat hij zich vanuit zijn paleis aan de oever van de Bosporus door een ondergrondse tunnel naar de Hippodroom begeeft voor zijn favoriete tijdsbesteding: de paardenrennen. De tunnel had hij voor zijn eigen veiligheid laten aanleggen want, net als Europese vorstenhuizen, was het bij de familie Comnenus voortdurend moord en doodslag en ook het volk was niet te vertrouwen. Die gebruikten de renbaan, met aan de twee uiteinden de Aya Sofia en het keizerlijk Paleis als de symbolen van de kerkelijke en de wereldlijke macht voor hun protestbijeenkomsten tegen het keizerlijk bestuur of voor vormen van volksvermaak als riddertoernooien, circussen en executies. Een hoogtepunt was het in 1118 levend verbranden van de leider der ketterse Bogomielen.

‘Hier vertonen zich mensen uit alle landen van de wereld met hun kunsten. Ze brengen leeuwen mee, luipaarden, beren, wilde ezels en laten die met elkaar vechten. Nergens anders ziet men een soortgelijk schouwspel,’ beschrijft een bezoeker aan de stad.

De binnenplaats van de Sultan Ahmetmoskee (Blauwe moskee)

Op de plaats waar nu de toeristen en inwoners van Istanbul in het Meydanipark tussen de Aya Sofia en de Blauwe Moskee een beetje rondslenteren over de betegelde paden, liep de langgerekte, 430 meter lange ovalen baan, waarop alle aandacht van de keizerlijke loge en de 30 duizend toeschouwers in de tribunes was gericht. Twee nog uit die tijd aanwezige getuigen fungeren als een nauwkeurige plaatsbepaling. Negenhonderd jaar geleden stonden ze al opgesteld bij een van de bochten van de renbaan, bijna aan het eind van het park. Een uit Egypte meegebrachte obelisk waarop keizer Theodosius in vier fragmenten staat afgebeeld tijdens zijn bezoek aan de paardenrennen en daar achter, een paar meter in de grond verzonken, de zogenaamde slangenzuil gevormd door drie in elkaar verstrengelde serpenten. Na de wedstrijd verdween Alexius door zijn tunnel richting paleis, maar ook daar maakte de overbevolkte binnenstad hem onrustig. In feite was hij bang en steeds op zoek naar een veilige plaats, maar angst tonen maakt kwetsbaar en voor zo’n belangrijke wereldse en kerkelijke vorst, misschien wel de machtigste van zijn tijd, waren voldoende vijanden voorhanden. ‘Ik heb behoefte aan frisse lucht’ liet hij steeds weten. Een kreet die klinkt als van deze tijd en die niet misplaatst is in het hedendaagse verkeersgekke Istanbul, maar het geeft ook een aardig beeld van de milieuomstandigheden rond het paleis van de keizer. Binnen de muren leefde hij tussen goud, marmer en brokaat, maar mogelijk kon de fijngevoelige neus van de keizerlijke hoogheid zelfs daar niet ontkomen aan de immer aanwezige stank van open riolen, dode dieren, smeulende vuren en drek en stront en moest hij zijn neus regelmatig deppen met de beroemde parfums uit de Bulgaarse rozenvallei. Steeds vaker verliet Alexius, begeleid door zijn getrouwen, op zijn witte paard de drukke binnenstad om zich over de Mese, de huidige Fevsi Pasja Boulevard naar zijn landelijk gelegen buitenverblijf het Blachernae te begeven. Het paleis staat vlak bij de Edirnepoort en met de achterzijde tegen misschien wel de veiligste muur van dat tijdperk gebouwd.

Hoe veilig zou spoedig blijken, want aan de andere kant van de muur verbeidde Godfried zijn tijd. Tenminste twee zaken hielden hem bezig. Wat moest hij met de halsstarrige Alexius beginnen, die hem voortdurend onder druk zette om een eed van trouw af te leggen en hoe lang zou het duren voordat de andere legers onder Bohemund, Raymond van Toulouse en Robert van Normandië hem hadden bereikt? Hij had behoefte aan steun en advies, want de gladde keizer wist steeds weer iets nieuws te bedenken om hem het bloed naar het hoofd te jagen. En de rol van Hugh Vermandois, de jongste broer van de Franse koning, beviel hem ook helemaal niet. Dat pedante Fransmannetje had zich door de keizer laten lijmen met geschenken en mogelijk nog wat vleselijke genoegens, om daarna zijn trouw aan Alexius te getuigen. En of dat nog niet voldoende was had de keizer Vermandois met zijn mooie praatjes naar zijn kamp gestuurd om hem op andere gedachten te brengen.

‘Schaam je je niet,’ had Godfried gezegd. ‘Jij verliet je land als een koning, met al die macht en een sterk leger. Nu heb je jezelf vanaf die hoogte tot het niveau van slaaf gebracht. En nu, alsof je grote successen zou hebben behaald, kom je hier naar toe en vraagt mij hetzelfde te doen. Ik heb trouw gezworen aan de Duitse keizer Hendrik IV en ik ga niet nog eens hetzelfde doen bij de keizer van Byzantium.’

‘Wij hadden in ons eigen land moeten blijven,’ antwoordde Hugh Vermandois ‘en onze handen van andere volkeren moeten afhouden, maar nu wij eenmaal hier zijn en de keizers bescherming nodig hebben, bereiken we niets wanneer we zijn orders niet gehoorzamen.’

Geïrriteerd zond Godfried de Fransman terug, waarop de keizer reageerde door de toegezegde voedselvoorraden te blokkeren. Uit woede begon Godfried op zijn beurt de dorpen in de omgeving te plunderen. De blokkade werd opgeheven, maar een paar weken later was het opnieuw raak. Om bescherming te zoeken tegen de koude winter had Godfried zijn kampement naar Pera verplaatst en daar was hij opnieuw door Alexius benaderd. Een nieuwe weigering werd gevolgd door weer een blokkade en al snel ontstond er gebrek aan paardenvoedsel, vis en brood. Toen besloot Godfried de stad aan te vallen. Delen van Pera werden geplunderd en in brand gestoken en op 2 april 1097 trok de Lotharingse Hertog de Gouden Hoorn over in de richting van het Blachernae, waar Alexius zich inmiddels definitief had gevestigd. Keer op keer werden aanvallen uitgevoerd op de Edirnepoort, maar met hun lichte wapens hadden de kruisvaarders geen schijn van kans. Niet tegen de poort, laat staan tegen de muur en toen de goed getrainde soldaten van Alexus de achtervolging inzetten, gaf Godfried na vier maanden beproevingen en irritaties op. Hij was bereid zijn loyaliteit te betuigen aan Alexius. De keizer hoopte met deze verklaring te voorkomen dat de Franken zich meester zouden maken van de Byzantijnse bezittingen op het Aziatische continent, maar zijn angst bleef en werd alleen maar groter toen ook de legers van de Fransen en de Italiaan Bohemund de stad naderden.

‘Toen keizer Alexius vernam dat Bohemund, die nobele man, in Constantinopel was aangekomen, gaf hij opdracht hem met alle eer tegemoet te treden. Voorzichtigheidshalve moest de ontmoeting buiten de stad plaats vinden. Toen Bohemund zijn tenten had opgeslagen, stuurde de keizer hem een boodschapper om en geheime ontmoeting af te spreken. Maar ook Godfried en zijn broer Boudewijn volgden Bohemund naar de stad en de toch al gespannen keizer raakte hierdoor ziedend van woede en probeerde een plan te bedenken om deze soldaten van Christus door list en bedrog gevangen te nemen. Maar door de hulp van bovenaf was er geen sprake van oneerbaar gedrag, noch door de keizer, noch door zijn mannen.’

De grote muur

Sultan Mehmet II

Voor de Edirnepoort, één van de vele poorten van de oude stadsmuur, stallen neringdoenden hun eenvoudige spulletjes uit. Kledingstukken in vaak venijnige kleuren, schoenen waar in veel gevallen geen stukje leer aan te pas komt, scheermesjes, aanstekers en nagelknippers. Karren, fietsen en ook auto’s passeren deze belangrijke ingang van de stad, waarvan de rijbaan maar net drie meter breed is. Daarmee is het nog één van de bredere doorgangen, want verderop langs de muur zijn de poorten soms zo smal, dat een man met een vlag en een fluit de hele dag het verkeer over de enige rijbaan staat te regelen. Hoe smaller de poort, hoe beter ze kon worden verdedigd! Naast de heel stevige, dubbele muren van Edirne Kapi hangt een bord met een Turkse tekst en het jaartal 1453. Het was een cruciaal jaar voor de stad, toen Mehmet II de poort vernietigde en de stad binnenstormde. Constantinopel werd Istanbul en de ondergang van het reeds verzwakte Byzantijnse rijk was bezegeld. De oorspronkelijke muur werd in de vijfde eeuw gebouwd en bestond uit een tien meter hoge voormuur met een achttien meter brede gracht en een vijftien tot twintig meter hoge achtermuur. Onder de nog in verrassend goede staat verkerende achtermuur heeft zich een geheel eigen cultuur ontwikkeld. In de enkele meters diepe poortjes wonen en werken families en allerlei ambachtslieden. Ieder plekje is benut. In de aangrenzende straatjes staan tussen winkeltjes en huizen af en toe, verborgen achter hoge muren, kleine met zorg onderhouden orthodoxe kerkjes op stille, vreedzame binnenplaatsjes. Een enkele keer is er alleen nog een poort met Hebreeuwse woorden en daarachter een parkeerplaats waar eens een synagoge stond. In het gebied tussen de voormuur en de achtermuur bevindt zich een chaotisch landschap met stukjes akkerland, grazende schapen, kleine bedrijfjes en rommelige huisjes waar mensen omheen scharrelen. Bij een caravan zitten zigeuners rond een vuurtje. Met oude planken is een hoekje afgescheiden waar drie paarden doodstil voor zich uit staan te staren. Straathonden scharrelen in de door de eeuwen heen ontstane bergen huisvuil, waarin archeologen hebben zitten wroeten om er gegevens uit te halen over de manier waarop de mensen eeuwen geleden leefden, aten en dronken.

Dicht bij de Edirnepoort verbreedt de muur zich tot een imposante vierkante ruïne, waarvan nog een aantal hoge muren van een drie verdiepingen tellend gebouw fier overeind staan. Ze vormen een deel van het Blachernae, de keizerlijke residentie die Alexius aan het eind van de elfde eeuw betrok. Na de val van Constantinopel woonde er tijdelijk een sultan. Daarna verviel het complex en werd het in de achttiende en negentiende eeuw gebruikt als porselein- en glasfabriek. Aan de buitenkant van de muur spelen wat jongetjes op een geïmproviseerd voetbalveld. Bij de ingangspoort schuift een vrouw het doek opzij van haar in de muur gebouwde hut en vraagt om geld. In de grote ontvangstruimte, waar de weelderige inrichting de kruisvaarders de adem benam, zijn de ronde bogen met de fraaie mozaïeken voor een deel intact gebleven…

Opwinding en huivering

Bohemund van Tarente

Op paaszondag 1097 verzamelde de elite van de kruisvaarders zich bij het Blachernae-paleis om de keizer de eed van getrouwheid af te leggen. Van de leiders waren aanwezig Godfried en Boudewijn, Robert van Normandië, Raymond van Toulouse, Hugh Vermandois en Bohemund van Tarente, Bohemund, die door geldgebrek weinig volgelingen had, had geen enkele intentie om het Heilige Graf te redden, maar was van plan om zich onderweg een eigen gebied met een titel toe te eigenen. Hij deed enorm zijn best om bij Alexius in de gunst te komen. Maar in de voorafgaande jaren was Bohemund in het leger van de Italiaanse Noormannen reeds twee keer tegen Alexius ten strijde getrokken en even zo vaak had de keizer het onderspit moeten delven. Niettemin trad de sluwe en gedistingeerde vorst hem met een glimlach tegemoet. ‘Heeft u een goede reis gehad en waar heeft u uw edelen ondergebracht?’

Fijntjes herinnerde de keizer hem ook aan hun eerdere ontmoetingen. ‘Ik was inderdaad een vijand,’ sprak Bohemund, ‘maar nu ben ik uit eigen wil als een vriend van zijne majesteit gekomen.’ De keizer converseerde nog wat door, maar probeerde onderwijl wat verder door te dringen in de verborgen gedachten van de kruisvaarder. En Anna, die aan de zijde van haar vader verbleef, huiverde, maar verhulde evenmin haar gevoelens van opwinding, toen ze de forsgebouwde Frank, waarover ze zoveel had gehoord voor het eerst ontmoette.

‘Bohemund was gelijk geen ander man die ooit het Byzantijnse rijk bezocht, Barbaar of Griek. Zijn verschijning veroorzaakte verbazing, het noemen van zijn naam paniek. Ik zal het uiterlijk van de barbaar beschrijven: hij was zo groot van postuur, dat hij vijftig centimeter boven de grootste mannen uitstak. Hij had smalle heupen en een platte buik, was breed in de schouders en had sterke armen. Zijn gestalte kan het best worden omschreven als mager noch gezet, maar zo perfect als maar mogelijk is, kortom gebouwd als het kanon van Polykleitos. Zijn handen waren breed, hij stond stevig op zijn benen en hij had een gedrongen hals en rug. Als je zorgvuldig naar hem keek, dan was het alsof hij enigszins een gebogen rug had. Niet dat zijn ruggengraat beschadigd was, maar het schijnt dat hij vanaf zijn geboorte deze vervorming heeft gehad. Zijn huid was heel wit, die van zijn gezicht zowel blozend als wit. Zijn haar was lichtbruin en hing niet tot op zijn rug zoals bij andere barbaren. Zijn haar was niet ruig, maar kort geknipt tot rond de oren. Ik kan niet zeggen of zijn baard rossig was of een andere kleur had, want hij was afgeschoren waardoor zijn gelaat zachter dan marmer was geworden. Zijn ogen waren grijs en drukten waardigheid en moed uit. Zijn grote longen deden de neusvleugels bewegen als hij ademde. Hij straalde charme uit, deze man, maar die werd deels teniet gedaan door de angst die hij om zich heen verspreidde. Want hij leek wreed en wild. Deels door zijn afmetingen, deels door zijn gedrag. Zelfs zijn lach boezemde de mensen angst in. Zowel moed als liefde leefden in hem en beiden waren gericht op oorlogsvoeren. Zijn ondernemende karakter durfde alles aan en verleidden hem tot allerlei acties. In zijn gesprekken gaf hij antwoorden die altijd dubbelzinnig waren. Dit was de aard van Bohemund en zijn lichaam en alleen de keizer was hem door diens welsprekendheid en andere aangeboren voordelen de baas.’

De keizer had plaats genomen op zijn troon en zich omgeven met veel uiterlijk vertoon. Hij wilde indruk maken op de barbaren, maar tegelijk verborg hij hiermee de zwakte van zijn in nood verkerende rijk. Gekleed in een purperen gewaad, bestikt met goud, hermelijn en marmerbont bleef hij op zijn zetel zitten, terwijl de edelmannen en hun ridders bleven staan. Op het moment waarop Alexius zich verhief en naar de edelen schreed om hun eed in ontvangst te nemen nam een van de ridders, Robert van Parijs, uitdagend, breed zittend plaats op de troon. De keizer gaf geen krimp, maar Boudewijn pakte Robert bij de hand en trok hem van de zetel.

‘Het is een schande om zoiets te doen,’ beet hij hem woedend toe, ‘en zeker nadat je de keizer trouw hebt gezworen. Romeinse keizers laten hun ondergeschikten niet naast zich zitten. Dat is de gewoonte hier en je dient de gewoonten van het land te respecteren.’ ‘Wat een boer, hij gaat zelf zitten en laat al die edelen staan’ beet de onbeschofte edelman de keizer nog toe, ‘maar Alexius hield wijselijk zijn mond, omdat hij de opvliegendheid van de Franken kende.’ Hij wilde maar één ding: zo snel als mogelijk het enorme kruisleger de Bosporus laten oversteken, weg van zijn hoofdstad, weg uit zijn rijk.

Aya Sofia

Aya Sofia

Op de gaanderij van de Aya Sofia-basiliek, weggemoffeld in een donkere hoek en onvindbaar voor wie de plaats niet kent, bevindt zich een van de zeldzame afbeeldingen van Alexius in zijn hoedanigheid als hoofd van de Byzantijnse Kerk. Als hogepriester staat hij, omgeven met de voorwerpen van zijn waardigheid, op de prachtige mozaïek afgebeeld met een halo achter zijn hoofd met de keurig verzorgde baard en snor. Meer dan duizend jaar vóór de Latijnen hun machtigste symbool, de Sint-Pieter in Rome, in de steigers zetten werd deze geweldige basiliek na twee branden en een aardbeving al voor de derde keer herbouwd. De laatste grote ramp vond plaats tijdens de vierde kruistocht, toen de kracht van Byzantium zo was verzwakt, dat de westerse christenen met steun van de machtige Venetiaanse vloot in 1204 kans zagen Constantinopel in te nemen en vol haat en jaloezie het symbool van het oosterse christendom op alle mogelijke manieren ontheiligden.

‘Ze gooiden de gewijde relikwieën van de heilige martelaren neer op plaatsen die ik nauwelijks durf te noemen. Ze namen de miskelken en hostiekelken en gebruikten ze, na er de juwelen en andere versierselen te hebben afgerukt, als drinkbekers… Ze sloegen het altaar stuk en verdeelden de stukken onder elkaar. Ze lieten ezels en paarden de kerk binnen om de heilige vaten mee te nemen, evenals het bewerkte zilver en het vermeil dat ze van de kansel, het pupiter en de deuren hadden afgetrokken, en oneindig veel andere voorwerpen. Sommige dieren waren op de zeer gladde tegelvloer gevallen; ze werden doorboord met het zwaard en bezoedelden de gewijde plaats met hun bloed en uitwerpselen. Een zeer zondige vrouw ging in de aartsvaderlijke stoel zitten, terwijl ze Christus beledigde, ze hief er een obsceen lied aan en danste vervolgens in de kerk, waarbij ze onfatsoenlijke bewegingen maakte.’

De Turkse Ottomanen veranderden de kerk na duizend jaar christelijke eredienst in Istanbuls belangrijkste moskee en bouwden er vier minaretten aan vast. Ze lieten de Byzantijnse iconen en mozaïeken met rust, maar ongewenste afbeeldingen werden met witkalk overgeschilderd. Sinds 1935 worden er geen diensten meer gehouden. Het historische gebouw is nu kerk noch moskee en wordt gebruikt als museum. De weggeschilderde afbeeldingen zijn weer tevoorschijn gehaald en drommen toeristen schuifelen hutje mutje de hoofdingang binnen, waar boven de deur een schitterende, pas in 1933 ontdekte mozaïek is aangebracht. In het midden bevindt zich op een troon de moeder Gods met haar kind op schoot en aan haar ene zijde staat keizer Constantijn de Grote met een maquette van zijn stad en aan de andere zijde Justianus met een model van zijn Aya Sofia. In de enorme centrale hal van de basiliek verstoren vier grote zwarte schilden met de namen van de eerste vier kaliefs de ruimtelijkheid. In het centrum bevindt zich een enorme bouwsteiger met een lift, die een internationaal gezelschap restaurateurs naar de hoogste regionen van de koepel brengt. Door het hele gebouw, de centrale hal, de galerijen en de zalen kunnen de symbolen van twee grote godsdiensten in harmonie naast elkaar bestaan. Mozaïeken van christelijke heiligen zijn aangebracht naast de mihrab, het poortvormige nisje dat de richting van Mekka aangeeft. Iconen van de Byzantijnse heersers bevinden zich naast afbeeldingen van de kaliefen en de kansel vanwaar de Koran werd gelezen.

Christenen en moslims

‘De vijandschap tussen het oosterse en het westerse christendom was in die tijd aanzienlijk venijniger dan de vijandschap tussen het oosterse christendom en de islam,’ zegt de Arabist Alexander de Groot van de Universiteit van Leiden, die een bezoek aflegt aan zijn collega dr. Ted LaGro, directeur van het Nederlands Instituut voor Academische Studies in Istanbul. De Groot vraagt zich af of de paus wel goed had nagedacht voordat hij zijn horden kruisvaarders op pad stuurde, want ‘de kruisvaarders hebben stelselmatig de veerkracht van de Byzantijnen verzwakt en daardoor juist de islam, zeg maar de Turken, de toegang tot Europa vereenvoudigd. De roomse Kerk is dus zeer onoordeelkundig te werk gegaan. Ze hadden in het Midden-Oosten met diplomatieke en culturele methoden hetzelfde kunnen bereiken zonder die ravage aan te richten in het oosterse christendom. De Byzantijnen zochten nota bene hulp bij de Turkse Seltsjoeken om zich tegen de Latijnen te verdedigen. Uiteindelijk trouwden er zelfs Seltsjoekse sultans met Byzantijnse prinsessen,’ aldus de Groot. LaGro heeft onder meer onderzoek gedaan naar de wederzijdse culturele beïnvloeding van de Kruisvaarders en de Moslims. Niet ver van het Instituut, aan de Istiklal Caddesi, bevinden zich nog wat restanten van de twee kerkgemeenschappen die elkaar al eeuwen naar het leven staan: een Grieks-orthodoxe en daar vlak bij maar liefst twee rooms-katholieke Kerken. Elders in de stad bevinden zich ook nog locaties van oosterse christenen en andere minderheden zoals de Syrisch-orthodoxen en Armenen.

De verhoudingen tussen de Turken en de Grieks-orthodoxe Kerk zijn heden ten dage ronduit slecht te noemen en regelmatig vertalen politieke spanningen tussen Griekenland en Turkije zich in religieuze uitbarstingen. Het aantal Grieks-orthodoxen wordt dan ook steeds kleiner en na iedere golf van geweld verdwijnen er weer groepen naar Griekenland, waar ze vaak in de omgeving van de grens onder meestal armoedige omstandigheden proberen te overleven. Het streng bewaakte orthodoxe patriarchaat in Istanbul staat qua proporties in geen verhouding tot het aantal gelovigen, maar hier zetelt dan ook de primes inter pares van de orthodoxe christenen, patriarch Bartholomeus de Eerste.

‘Hoe is het tegenwoordig met de verhoudingen tussen de orthodoxen en de katholieker?’ was een van de vragen die hij had moeten beantwoorden, maar ook hier werden (net als bij het Servisch-orthodoxe patriarchaat in Belgrado) faxen en brieven niet beatwoord, afspraken niet nagekomen door geestelijken die zich afwezig meldden, maar er wel bleken te zijn. ‘Misschien helpt het als u orthodox wordt,’ prevelt Bartholomeus’ secretaris, deken Tarasios, vriendelijk.

‘De relatie met de orthodoxen is tegenwoordig uitstekend’ zegt Pater Dario van de rooms-katholieke Kerk en voegt eraan toe: ‘in Turkije worden de minderheden erkend en getolereerd.’ Dario, die schat dat er nog een kleine 100 duizend rooms-katholieken in Turkije rondlopen, wandelt door zijn kerk naar de achterkant van het altaar, waar hij bij een van de poten zeer demonstratief naar een in het tapijt gebrande schroeivlek wijst. ‘Dit is eind mei (1994) gebeurd,’ zegt hij met een smartelijk gezicht, ‘en de politie weet niet wie de brandbom heeft geplaatst. Mogelijk zijn het fundamentalisten geweest. Een vorm van aandachttrekkerij.’ In de Turkish Daily van 28 oktober vraagt de Armeense patriarch Kazanciyan de Turkse regering om een onderzoek te beginnen naar de herkomst van een serie dreigbrieven, die de Armeense gemeenschap heeft ontvangen van een van de Istanbulse nationalistische bewegingen. ‘Parasieten’, luidt de aanhef van een van de brieven, ‘jullie denken misschien dat je in dit land thuis hoort. Maar vergeet nooit dat Turkije alleen voor de Turken is.’

In het vervolg van de brief worden de nodige gewelddaden aangekondigd om de ongewenste elementen te elimineren.

De Neve-Shalomsynagoge in de oude joodse Balat wijk bij de Galata-toren blijkt al langere tijd officieel gesloten te zijn. De reden van sluiting was een PLO-aanslag in 1986 waarbij 23 doden vielen. In 2003 volgde een nieuwe aanslag. Het is vrijdagavond en dus sabbat. In het schemerduister staan in een van de smalle straatjes van de wijk een paar mannen met hoedjes, die op het punt staan een kleine metalen deur binnen te gaan. Een politieman fouilleert de bezoekers die daarna over een binnenplaatsje naar een vrij grote synagoge wandelen, waar de rabbijn, ondanks het feit dat de paar aanwezige mannen de minjan (voorgeschreven minimum van tien mannen om een dienst te kunnen beginnen) niet hebben gehaald, met zijn dienst is begonnen. De meeste joden zijn in de jaren zeventig naar Israël vertrokken. Later staat in een krant te lezen, dat de voorzitter van de joodse gemeenschap in Ankara licht gewond is geraakt bij de ontploffing van een in zijn auto verstopte bom. De onbekende groep Turkse idealistische commando’s voor sharia eiste de aanslag op.

Scheermesjes tegen blote benen

Clock bearing emblem o.t banned party Refah Partisi

Op het platteland en dan vooral in verre streken als Anatolië is het aantal aanhangers van minderheidsgodsdiensten de laatste jaren snel afgenomen. Te veel kerken en mensen werden het doelwit van aanslagen van fundamentalistische bewegingen. Veel aanhangers van de bedreigde groepen zijn naar Istanbul getrokken en mét hen een meervoud aan arme plattelanders, die vroeger hun geluk in Nederland en Duitsland zochten en nu in deze stad zijn neergestreken in gezelschap van leden van de radicalen rond de Refah Partij en allerlei andere fundamentalistische clubjes met extremistische ideeën.

Tussen 1980 en 1995 groeide het aantal inwoners van drie naar ongeveer dertien miljoen. ‘Dorpsturken’ worden ze genoemd, omdat ze buiten de stad maar ook erbinnen volledige dorpen hebben gevormd. De Refah Partij heeft hier goed garen bij gesponnen en onmiddellijk na het winnen van de stadsverkiezingen in 1992 is hun burgemeester Erdogan in de aanval gegaan tegen de ‘verderfelijke westerse invloeden.’ ‘Vrouwen met korte rokken werden door de aanhangers geslagen en van meisjes werden de zichtbare delen van de benen met scheermesjes verminkt. Leidingwater mocht geen chloor meer bevatten, omdat dit de wassing voor het gebed zou verstoren. Open tbc kostte toen tientallen mensen die van het ‘zuivere’ water hadden gedronken, het leven.’ Door dergelijke krantenberichten kijken westerlingen tegen Istanbul aan als een zeer islamitische stad, terwijl de stad altijd een liberaal, westers georiënteerd karakter heeft gehad. Het merendeel van de autochtone bevolking ziet echter nooit een moskee van binnen, zoals het merendeel van de bevolking van Amsterdam nooit naar de kerk gaat. Zij zien Amsterdam als een christelijke stad. Wij zien Istanbul als een islamitische stad. De oorspronkelijke bewoners maken zich grote zorgen over de toekomst, want het aantal fundamentalisten blijft maar groeien.

Oude wijn in nieuwe zakken

‘Het lijkt wel of ze vanuit de kelder of vanonder de trap vandaan zijn gekomen met hun fundamentalistische ideeën,’ aldus Halil Berktay, professor in de vergelijkende geschiedenis aan de Bosporus Universiteit, ‘en de aanval van Erdogan op die verderfelijke westerse elementen is daar een voorbeeld van.‘

Berktay bewoont een flat in de buitenwijk Büyukdere, zo’n beetje op de plaats waar Godfried uiteindelijk de Bosporus overstak. In zijn studeerkamer zijn de wanden volledig dichtgegroeid met boeken die, gezien hun onderscheiden karakter, voortdurend met elkaar in een fluisterende dialoog verwikkeld moeten zijn. Hij legt zijn boek van Céline terzijde en zegt ‘Telkens als Turkije iets misdaan heeft op het gebied van de mensenrechten en het Westen protesteert hier tegen, dan reageren ze als door een wesp gestoken en wordt het beeld van de kruisvaarders weer van stal gehaald. In Turkije zijn ze dan bang dat dit een hernieuwde poging van de westerse christenen is om de Turken, de Ottomanen, nog eens te straffen voor hun eeuwenlange overheersing van grote delen van Europa. De kruistochten waren diep weggezonken in de herinnering van de Turken, maar de fundamentalisten hebben kans gezien er een aantal bruikbare elementen zoals het idee van de Jihad uit te halen voor hun propaganda,’ zegt Berkay.

‘Oost en West doen wat dat betreft niet voor elkaar onder als het gaat om het simplificeren van de beeldvorming. Kijk maar naar onze geschiedenisboekjes. In de jaren tachtig en negentig is ook daar weer een opleving merkbaar van het Turkse standpunt. De kruisvaarders worden, niet ten onrechte, als verkrachters en plunderaars beschreven en het christendom als een gewelddadige religie.

‘Kijk maar naar Bosnië,’ zeggen de fundamentalisten. ‘Waarom doet Europa niets tegen het geweld’?

‘Omdat,’ zeggen ze, ‘Servië in het geheim steun krijgt tegen de moslims.’

In sommige kringen wordt zelfs gedacht dat Europa graag het Byzantijnse rijk wil herstellen. Een gedachte, die samenhangt met de ‘orthodoxe as’ tussen Moskou en Athene. Deze groepen denken dat het patriarchaat van de orthodoxe Kerk in Istanbul een soort Vaticaan wil hebben, een autonoom gebied binnen de Republiek Turkije. Als een onderdeel van de samenzwering van het Westen tegen de Turken. We moeten af van deze ‘wij christenen – zij moslims’ gedachte,’ eindigt Berktay zijn betoog, ‘anders krijgen we – en in Bosnië ligt het begin – een soort herhaling van de scheiding in een christelijk en een moslimblok zoals in de elfde eeuw ten tijde van de Kruistochten.’

Robert Mulder & Lejo Siepe – God wil het! Reizen in het spoor van de kruisvaarders

Rozenberg Publishers 2005 ISBN 978 90 5170 168 5