Telkens weer op zoek. In de sporen van de Recherche van Proust

De grote werken uit de Modernistische periode nodigen wellicht des te meer uit tot navolging en imitatie omdat ze zelf vaak variaties zijn op oudere kunstwerken. Ulysses en De dood van Vergilius zijn sprekende voorbeelden die bewijzen dat mimicry en citationisme blijkbaar niet voorbehouden zijn voor een postmoderne aanpak. In deze bijdrage willen we aantonen dat het inhaken op beroemde voorbeelden om deze op eigen wijze te verwerken ook tot een soort ‘vormdwang’ kan leiden (of sterker gezegd – met een lacaniaanse ondertoon – dat deze dwang inherent is aan zo’n onderneming). In ons geval zal het daarbij – in het kader van de voorliggende bundel – vooral gaan om aan te tonen dat kunstwerken die tijdens de laatste decennia als voorbeeld, oriëntatiebron of uitgangspunt Op zoek naar de verloren tijd van Marcel Proust hebben gekozen, als vanzelfsprekend karaktertrekken van het modernisme hebben overgenomen. Uiteraard gaat het hier om complexere processen dan alleen vormdwang, zoals bijvoorbeeld een ‘terugkeer naar het modernisme’ of, genuanceerder, een innige verstrengeling van modernistische en postmoderne componenten.

Als Jacqueline Harpman in Orlanda (Prix Médicis 1996) op speelse wijze omgaat met de gegevens uit Virginia Woolfs Orlando, gaat dit gepaard met allerlei auctoriale knipoogjes en postmoderne springerigheid (met betrekking tot personages en motieven, maar ook qua compositie en stijl). Toch kunnen deze flikkerende versieringen en huppelende danspasjes niet wegnemen dat de kern van de zaak het zoeken naar identiteit betreft, alsmede de crisissituaties die dat met zich mee brengt, waarbij verhaaltechnisch het perspectivisme de toon zet. Het feit dat Harpman zelf psychoanalytica is heeft overigens wellicht een royale duit in het zakje gedaan (de psychoanalyse is een bij uitstek modernistische discipline).

Wanneer Willem Brakman in De bekentenis van de heer K. (1985) in het voetspoor van Kafka’s Josef K. treedt, wordt de trefzekere ‘eenvoud’ van diens proza behoorlijk gepimpt. Brakman transplanteert zijn visie op Kafka naar zijn eigen variant op Het proces. Die visie verwoordde hij ooit als volgt (in een essay over Kafka): “Zijn overkwetsbaar naturel, al in de prille jaren scheefgetrokken, verwrongen en vervormd, zorgde voor de zo nodige maniakale trekken” (in Brakman, 2001). Maar ook al krijgt de wereld van K. bij Willem Brakman eveneens maniakale trekken (een soort intertekstuele pervertering)[i], toch heerst in die tekst eenzelfde gevoel van ‘unheimlichkeit’, omdat achter de barokke stijlexercities de kilte van een gemechaniseerde wereld zich opdringt.

Een derde voorbeeld vinden we in de roman Les Bienveillantes van Jonathan Littell uit 2006 waarin een vroegere SS-officier tot in de gruwelijkste details verslag uitbrengt over zijn rol in de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Uiteindelijk blijkt dat familieverhoudingen uit zijn jeugd de verklaring tot zijn persoonlijkheid vormen. Enerzijds grijpen deze terug op een mythologische achtergrond (de Orestes-verhalen); anderzijds is een intertekstuele relatie met Musils Mann ohne Eigenschaften (met name wat betreft de broer-zus verhouding in dat werk) herkenbaar. Hoewel Littells roman opgevat kan worden als een gigantische stijloefening, een compositorische puzzel die bijvoorbeeld met Tolstoï wil wedijveren, kan men zeker ook door de verwijzingen naar de Oudheid en de daaruit voortvloeiende cyclische geschiedenisopvatting een modernistische gelaagdheid in het verhaal terugvinden.

Voor wat betreft de sporen en herscheppingen van modernistische kenmerken in het werk van Proust zullen we in het volgende een blik werpen op realisaties vanuit twee verschillende media om tevens aan te tonen dat deze tendens een transmediaal karakter vertoont, zij het met telkens specifieke eigenschappen. Eerst blijven we bij de literatuur en bekijken de roman Octave avait vingt ans van Gaspard Koenig uit 2004. Vervolgens komt de stripbewerking ter sprake waarvan Stéphane Heuet tot op heden vijf delen publiceerde.

Octave avait vingt ans

Het debuut van deze jonge auteur van 22 jaar oud werkt in principe een uitgesproken postmodern procédé uit. De schrijver nestelt zich in een luwte/leegte van de Proustiaanse tekst om daar een soort pastiche op te richten. Het is imitatie in de tweede macht want ook Proust was in zekere zin zijn carrière als pastiche-schrijver begonnen. Het lijkt er echter op dat Koenig verder wil gaan door eigen materiaal toe te voegen: zo wordt de pastiche tot een soort van collage of zelfs tot een meer vrije variant op een thema.

Octave als personage van Proust is het vertrekpunt voor Koenig. Octave doet zijn intrede in de Recherche tijdens het eerste bezoek van de hoofdpersoon en (latere) verteller Marcel aan Balbec en hij duikt ook weer op bij een tweede zomers verblijf in die (fictieve) Normandische badplaats.

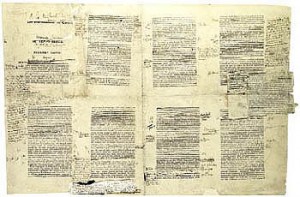

Kœnig heeft een vijftiental fragmenten hernomen die in grote lijnen alle tekst over Octave – op het eerste gezicht een vrij bijkomstig figuur – bij Proust beslaan. Hij heeft die lijnen uitgewerkt maar ook passages toegevoegd die zich tamelijk ver van de oorspronkelijke tekst verwijderen. Laten we daarom eerst eens kijken welke rol Octave in de Recherche speelt.

Wanneer deze in Balbec opduikt (in de gesprekken van de habitués van het badhotel) wordt hij gekarakteriseerd als een « Joli Monsieur » die elke dag luncht met champagne, « een orchidee in zijn knoopsgat »[ii], en die vervolgens « bleek en onbewogen met een onverschillige glimlach op zijn lippen in het Casino aan de baccarattafel enorme sommen geld inzet die hij eigenlijk niet zou mogen verliezen […] » (II 38)[iii]. Zijn vader heeft uitgebreide bezittingen in Balbec, wat de grillen van zijn aamborstige dandy-achtige zoon mogelijk maakt. Op een goede dag komen Marcel en zijn vriendin Albertine hem tegen: « Koeltjes en zonder emoties te tonen – wat hij blijkbaar beschouwde als het toppunt van stijl – zei hij goedendag aan Albertine – ‘Kom je van het golfterrein, Octave?’ – ‘Oh! Daar word ik zo moe van, ik ben in de bonen’, antwoordde hij. » (II 233). En zo ontstaat een vreemde bijnaam: « Octave dans les choux », letterlijk ‘Octave in de kolen’. Dan volgt een lange uitweiding waaruit blijkt dat Octave een goede danser is en zeer verfijnd wat betreft kleren, sigaren, Engelse drankjes en paarden, maar dat hij geen greintje intellectuele cultuur bezit. Albertine houdt hem voor een « gigolo ».

Maar dat is niet het hele portret. Allereerst gaat Octave een belangrijke rol spelen met betrekking tot het netwerk van relaties in de Recherche: hij is een neef van de Verdurins (prototypes van de ‘haute bourgeoisie d’argent’), hij is een tijdlang de minnaar van de actrice Rachel, maar bovenal trouwt hij met Andrée, vriendin en rivale van Albertine. Uiteindelijk wordt er zelfs gewag van gemaakt dat hij Albertine zou hebben willen ontfutselen aan Marcel (wanneer deze haar van iedereen tracht af te zonderen in la Prisonnière) en dat hij haar vlucht zou hebben gestimuleerd (gevolg van een oud plan van de tante van Albertine om een huwelijk tussen haar nichtje en Octave te arrangeren).

Maar het ware belang van Octave is nog ergens anders in gelegen: hij wordt een toonaangevend auteur met zijn « petits sketches ». De verteller tracht dit fenomeen te verklaren. Onder anderen denkt hij aan een “fysiologische” ommezwaai die van de lompe botterik een “schone slaapster” heeft gemaakt (IV 184). De verteller geeft toe dat hij zich kan hebben vergist en komt tot het inzicht dat blijkbaar “misschien wel de mooiste kunstwerken van onze tijd hun oorsprong vinden in een geregeld verblijf op de renbaan of in de grands cafés” (IV 186).

Men heeft modellen gezocht voor deze Octave onder wie Jean Cocteau, maar hij is natuurlijk allereerst een dubbelganger van Marcel (het neefje van « tante Octave », zoals de beroemde tante Léonie ook wel genoemd wordt, naar haar overleden man). Het laatste optreden van Octave in de roman toont ons een auteur die rivaliseert met de ballets russes van Djagilev en die zich helemaal aan zijn œuvre wijdt, terwijl zijn ziekte hem dwingt thuis te blijven en hij alleen nog voor “enige ontspanning” mensen ontvangt (we herkennen Proust in zijn latere levensperiode).

Een van de merkwaardigste passages betreffende Octave gaat over de herinnering, centraal thema bij Proust, dat hier op een specifieke wijze naar voren komt:

Een van de prominente figuren in die salon was Dans les choux, die zich ondanks zijn voorliefde voor sport had laten afkeuren. Ik zag hem nu zozeer als de schrijver van een schitterend œuvre waar ik voortdurend aan dacht, dat ik alleen wanneer ik bij toeval de band legde tussen twee reeksen herinneringen, bedacht dat hij ook degene was die het vertrek van Albertine had veroorzaakt. Trouwens die dwarsverbinding liep wat betreft de resten van herinneringen aan Albertine uit op een dood spoor van jaren her. Want ik dacht nooit meer aan haar. Die herinneringen gingen een richting uit die ik nooit meer insloeg. Het werk van Dans les choux daarentegen was recent en dat spoor volgden mijn herinneringen voortdurend. (IV 309)

Voor Marcel luidt de boodschap: scheppend kunstenaarschap overwint elke rouw, maar tegelijkertijd worden de resten (“reliques” in het Frans, met een religieuze ondertoon) juist in genoemde “dwarsverbinding” tussen herinneringen wel weer gezegd.

Terug naar Kœnig nu. Hij schrijft over Octave een roman van 210 pagina’s en er is dus sprake van amplificatie. De citaten (in cursief) leggen de nadruk op de dandy-achtige aspecten. Octave zal bij Koenig nooit tot een scheppend kunstenaar uitgroeien. Kunst speelt hier meer een rol in de persoonlijke relaties zoals die met de vader van Octave:

Voor Octave was dat kunstwerk iets zo intiems, iets dat zo zeer leefde binnen zijn geheimste innerlijk, dat hij er nooit over zou kunnen praten zoals zijn vader voor wie kunst hetzelfde betekende als mooie auto’s voor Octave. (61)

Bij Proust kunnen we lezen:

Voor Octave was kunst waarschijnlijk iets zo intiems, iets dat zo zeer leefde binnen zijn geheimste innerlijk, dat hij er nooit over zou kunnen praten zoals Saint-Loup bijvoorbeeld voor wie kunst hetzelfde betekende als een rijtuig met paarden voor Octave. (IV 186)

In zijn proloog schrijft Kœnig met betrekking tot de citaten: “Soms zijn ze enigszins aangepast aan de context om bijvoorbeeld anachronismen te voorkomen.” De vervanging van de vriend door de vader hier gaat duidelijk verder vooral omdat het schilderij dat die vader (‘el Torero’) verwerft een doek van Goya betreft, “Saturno devorando a un hijo”.

Een andere intimiteit schemert zo door. De dandy van Proust is wellicht ontleend aan het personnage van Octave in de Confessions d’un enfant du siècle van Musset. Bij Kœnig is er ook sprake van een “geheime verwonding” die zijn sexualiteit betreft en die eerder doet denken aan Octave, de held uit Armance van Stendhal, op wiens impotentie ook op die wijze wordt gezinspeeld. Voor Koenigs Octave zou Elise, de dochter van de « koning van de parfums », (als een soort Madeleine[iv]) dit gemis moeten opheffen. Zij wil voortdurend verrast worden, en Octave voelt maar al te goed dat hij als een « impuissant dévot » steeds tekort schiet (56).

Na de openingshoofdstukken over de kinderjaren en de tijd op school, volgen er vier gedeelten over zijn relatie met Elise, tekens gemarkeerd door de angst verlaten te worden. Wanneer het over zijn prestaties in het schermen gaat doemt de voornaamste rivaal op in de persoon van Louis Roger wiens superioriteit hij erkennen moet. Vervolgens opent de relatie met Camille een venster op de Oudheid (« Octave versloeg Marc-Antoine zoals eertijds het gevecht tussen de twee erfgenamen van Caesar was afgelopen », 108), maar ook deze relatie brengt geen vervulling. Steeds overvloediger wordt dan het arsenaal aan personages en gebeurtenissen zonder echter het existentiële gemis te kunnen opheffen.

Het volgende hoofdstuk speelt op de renbaan en Octave wint daar een belangrijke prijs vooral door zijn perfecte samenwerking met zijn paard. Na afloop onderwerpt hij Elise op soortgelijke wijze. Het hoogtepunt van hun relatie vindt plaats in Venetië waar Elise zich in dezelfde Fortuny-gewaden kleedt waar Proust zo dol op is. Het Canal Grande en het Casino vormen het decor voor hun omzwervingen, maar Octave ontkomt er niet aan hallucinaties waarin een bedreigende moederfiguur opduikt. In werkelijkheid gaat het om beelden van Botero die zijn uitgestald op de kades: “Een kolossale vrouw, donker en lekker, zo groot als de reus die Octave verslond [die van Goya], wellicht zijn nachtelijke gezellin” (170).

De zes etappes van Octaves ‘éducation sentimentale’ in Koenigs tekst zijn in feite een flashback bij de proloog die door de epiloog wordt hernomen in een cyclische beweging die ook weer aan de Recherche doet denken.

In het begin loopt men over het strand waar in de epiloog Elise zich aan de rivaal van Octave overgeeft tijdens een soort archaïsche rite waarbij het strand in een kathedraal verandert. Proust vergelijkt eveneens de Recherche met een kathedraal en ook bij Koenig wordt de artistieke dimensie in het portret van Octave zo ingevuld. De kathedraal waar het hier om gaat is die van Antwerpen. De seksuele scène op het strand smelt op fantastische wijze samen met een uitvoering van la Forza del Destino tussen de doeken van Rubens die in die kathedraal hangen. De geëxalteerde dirigent, van der Voort, overleeft de climax van dit tijdloze drama niet. Kunst verbeeldt dood, geweld en genot waarna Octave achterblijft in zijn verlatenheid.

Postmoderne barokelementen waar pastiche en kitch zich verstrengelen vormen een opzichtige oppervlakte van de tekst waaronder echter modernistische motieven krachtig doorklinken: identiteitscrisis, de geboorte van het kunstwerk, de spiegeling van de autonome tekst. De metamorfose kan zo worden gedefinieerd: Octave is tot een muzikaal octaaf geworden: de acht etappes van zijn omzwervingen zijn uitgemond in de apotheose van de “octave supérieure”. Het hoogtepunt is ook een verstening, een doodssculptuur, zoals bij Verdi in la Forza del Destino, of zoals in het laatste gedeelte van de Recherche (het ‘bal de têtes’ waar de Proustiaanse personages in een soort fantomen veranderen). De ‘held’ gaat bij Koenig ten onder, maar de kunst zegeviert. Wat is er romantischer, postromantischer, modernistischer?

Gaspard van de Nacht (zoals het hoogromantische cultboek van Aloysius Bertrand heet) die met de naam van zijn moeder (Anne-Marie Koenig) signeert, is wellicht ook de koning uit het oosten die Christus komt bewieroken. De mysterieuze Octave uit de Recherche is in zijn ongrijpbaarheid een dubbelganger van de auteur en die andere Octave die twintig jaar oud was volgens de titel staat ook heel dicht bij de schrijver van een nieuwe generatie.

Proust verstript

Ook in andere media is de Recherche als uitgangspunt gebruikt. Vele schilders maakten illustraties (bijvoorbeeld zeer aansprekende Van Dongens) en als verfilmingen zijn vooral Un Amour de Swann van Volker Schlöndorf en Le temps retrouvé van Raoul Ruiz bekend. Chantal Akerman breidt in La Captive voort op het verhaal rond Albertine en verder zijn de scenario’s van Visconti en vooral van Pinter interessant (deze laatste inspireerde ook ten zeerste Guy Cassiers voor zijn toneelbewerking bij het Ro-Theater)[v]. Ook het ballet “Les Intermittences du coeur” van Roland Petit uit 2007 dient vermeld te worden.

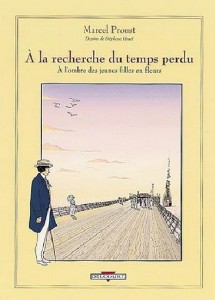

Net als film heeft het stripverhaal steeds een nauwe band gehad met de ‘grote literaire’ teksten. Vaak ging het daarbij erom die teksten voor een groter publiek toegankelijk te maken. Dat is ook een van de beweegredenen van Stéphane Heuet die tot nu toe “Combray”, “A l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs” (twee delen) en “Un amour de Swann” (twee delen) bewerkte. Deze albums werden ook in het Nederlands vertaald en verschenen bij uitgeverij Atlas.

De vormgeving van de albums is traditioneel (Combray telt 72 pagina’s van 32 bij 23 cm; de andere delen 48 pagina’s van hetzelfde formaat). Het kader van de buitenkant is klassiek, monumentaal, met de gelige kleurstelling van oude foto’s. Het lijkt op lijsttoneel waar verschillende omlijningen de scène inkaderen. Zo wordt de monumentale aard van de Recherche benadrukt maar ook de theatrale dimensie van het werk. Op de grens van de kaders begeleidt telkens een afgebeeld personage de overgang. Bij Combray is dat de verteller die de lezer vergezelt naar de wereld van het kind. Deze nadruk op de constructie is meteen heel modernistisch van aard.

Bij Les Jeunes Filles 1 wordt de volwassen verteller die de belevenissen aan zee van de jongeman in het boek gaat verhalen geplaatst op een lange pier waarvan het perspectief de vluchtlijn van de herinneringen lijkt aan te geven.

In Les Jeunes Filles 2 combineert de omslag twee belangrijke gebeurtenissen: enerzijds het bezoek aan het atelier van de schilder Elstir, die een belangrijk voorbeeld zal zijn als kunstenaar, en anderzijds het verschijnen van de sportieve Albertine. Het spel met de kaders (en dus met de conventies van het stripverhaal) is hier geraffineerd: we zien een atelier waar de zeegezichten van Elstir hangen terwijl hij zelf net bezig is een zonsopgang boven zee te schilderen. Albertine duikt op in het kader van het raam, op één lijn met de jonge bezoeker aan het andere uiteinde van het atelier. Maar deze laatste zit in feite half buiten het beeld op een krukje en houdt een portret uit een andere periode van Elstir in de hand (Odette, de latere Madame Swann, als actrice). Elstir is de schilder van picturale metamorfoses tussen land en zee: naar die kunst van de metafoor gaat de jongeman toegroeien waarbij hij de liefdesrelaties achter zich zal laten. Met Albertine verkeerde hij eigenlijk nooit in hetzelfde kader. Deze allegorische uitbeelding strookt heel goed met de modernistische dimensie van de Recherche.

Un amour de Swann tenslotte toont ons Swann die het kader in/uitstapt dat door het huis van Odette wordt aangereikt, een kader waarbinnen schaduwen een ander koppel laten zien. Men kan het beschouwen als hallucinaties van Swann die zijn rivaal daar projecteert terwijl hijzelf door dat kader buitengesloten wordt. Zo vertelt de kaft al de kern van het verhaal in een soort ‘mise en abyme’, sinds Gide een modernistisch principe bij uitstek. Op de cover van Swann 2 vliedt in een soortgelijke spiegeling Odette henen, ongrijpbaar zoals vrouwen nu eenmaal ongrijpbaar zijn.

De paratekstuele aspecten wijzen op een hoogst gestructureerde aanpak. Dit is ook het geval voor de globale opzet: het doel is in dienst te staan van de Proustiaanse tekst. Dit komt allereerst naar voren in de citaten. Elke pagina staat er vol mee en ze bevinden zich in duidelijk afgebakende vakken met een specifieke kleur (eigeel). Het album wordt zo een soort condensé van de Recherche, een opeenvolging van kernpassages waarbij ook de stijl hernomen wordt (met lange series adjectiva bijvoorbeeld). Wanneer de lengte in de tijd als hoofdkenmerk van het werk van Proust zo verdwijnt, wordt dit in zekere mate gecompenseerd door een goed gedoseerd gebruik van ritme en herhalingen. Met name het feit dat de Recherche is opgebouwd rond een aantal kernscènes wordt in de stripversie benadrukt. Vooral de scènes met een sterk toneelkarakter zijn in de meerderheid. Het eerste album van de Jeunes Filles is zo als volgt opgebouwd: de aankomst in Balbec; de intrek in het Grand Hôtel; de ontmoeting met Mademoiselle de Stermaria (object van één van de liefdesprojecties van Marcel); de kennismaking met madame de Villeparisis (oude adel en vriendin van grootmoeder die Marcel begeleidt); uitstapjes; Saint-Loup arriveert (de vriend bij uitstek); grollen van Bloch (een Joodse kameraad); eerste contacten met Charlus (de oudere homosexueel); het verschijnen van de bloemenmeisjes (Albertine en haar vriendinnen). De gebeurtenissen betreffen vooral personen en zetten zo de deur open voor psychologische bespiegelingen en het werken met meerdere perspectieven, modernistische principes bij uitstek. Het herhalende karakter van Prousts tekst vindt zijn natuurlijke weerslag in de identieke weergave via simpele lijnen en trekken van de personages bij Heuet. In zekere zin kan dit corresponderen met de bedoeling van Proust: veranderingen grijpen plotseling en onverwacht plaats. Maar de karakterisering van de personages vertoont wel een behoorlijke simplificatie.

Het personage staat doorgaans centraal in het stripverhaal en heeft een repetitief karakter. De herhaling in gedragingen en de terugkeer van personages zijn ook heel belangrijk voor Proust. Voor de tekeningen van Heuet heeft Marie-Hélène Gobin opgemerkt dat de jonge Marcel sterk aan Kuifje doet denken en dat Françoise, de trouwe huishoudster, lijkt op Bécassine, een ander traditionele Franse stripfiguur.

Die conclusies kunnen worden doorgetrokken naar onder anderen Albertine, Charlus, Saint-Loup, de Verdurins, dokter Cottard of Swann. Tekeningen zoals bij Hergé met duidelijk afgebakende figuren en scherpe contouren, voorzien van slechts enkele kenmerkende trekken beantwoorden aan een eerste visie van Proust – zoals de jonge Marcel de wereld in eerste instantie bekijkt.

Maar bij Proust wordt het beeld al snel gecompliceerder: de bijfiguren behouden weliswaar ‘levenslang’ hun stereotype verschijning (en Heuet profiteert daarvan), maar de hoofdrolspelers ondergaan vele veranderingen en zijn ook geregeld omgeven door een waas van geheimzinnigheid. Bij sommige personages is de reden van hun veelzijdige verschijningsvormen gelegen in de uiteenlopende instellingen waarmee men (en allereerst hier natuurlijk de verteller) de ander bekijkt met een blik gevoed door het verlangen; bij anderen (zoals Octave, maar ook Elstir en Vinteuil, de schilder en de componist) ligt het aan het feit dat ze als kunstenaar een belangrijke evolutie ondergaan

Heuet heeft er niet naar gestreefd om deze tweede dimensie weer te geven en een bescheiden poging in die richting bij het portret van Albertine is niet erg overtuigend. Een dansend vlekje kan maar heel gedeeltelijk de altijd wegvluchtende en ongrijpbare natuur van de geliefde aanduiden.

Marcel is het meest complexe personage van allemaal te meer omdat hij als vertellende instantie zoveel verschillende verschijningsvormen van de “ik” bijeenbrengt. Marcel is het knaapje in matrozenpak, hij is ook de nieuwsgierige, wat bangelijke adolescent, en verder de teleurgestelde man van de wereld maar ook de schrijver die helemaal in zijn werk opgaat. Hij is dat allemaal tegelijkertijd, want hij zoekt zichzelf, zijn eigen tijd en zijn roeping, een roeping die samenvalt met ons leesproces.

De Recherche van Heuet is daarom in zekere zin trouw aan de tekst van Proust, maar in een afgezwakte versie die (noodzakelijkerwijs ?) de verschrikking en de zaligheid van dat steeds weer verliezen van zichzelf uit de weg gaat.

Semantische ketens en verbanden

In zijn studie van de ‘bande dessinée’ legt Thierry Groensteen terecht de nadruk op het belang van de macrostructuur waar de microstructuur van afhankelijk is, en hij onderstreept de rol van de combinaties (de « arthrologie », verbindingen tussen verschillende niveaus) als ook de vorming van semantische ketens (de terugkeer van bepaalde elementen als refrein of echo). De lezer brengt die verbindingen tot stand en vult de afstand tussen de afbeeldingen zo op. Voor wat betreft de relatie tussen de tekst van Proust en het stripverhaal zou het essentieel zijn een goede formule te vinden voor de o zo belangrijke vorming van ketens in de Recherche.

Herhaling is bij hem differentie. De terugkeer van het identieke is de utopie van het buitentijdelijke. De semantische keten heeft ook artistieke waarde: wat in de mensen uiteenvalt en verbrokkelt kan in het kunstwerk samenklonteren. De verschillende verschijningen van Swann, de omvorming van Elstir, Odette die evolueert van Miss Sacripant tot madame Swann, Albertine de ongrijpbare, de ‘ik’ die zich over zichzelf blijft verwonderen: bij Heuet verhindert het eendimensionale karakter een weergave van deze constante verschuivingen en onzekerheden. Anderzijds is er wel geregeld sprake van een creatieve zoektocht om de mogelijkheden van de vormgeving zo goed mogelijk te exploiteren.

Combray, het eerste album uit de serie, volgt vrij trouw de tekst van Proust. Het familieleven in Combray met de bezoekjes van Swann, met oom Adolphe, Françoise en de allegorische keukenmeid, de « Charité van Giotto », wordt genoemd; het lezen in de tuin, de wandelingen, de ontdekking van de schrijver Bergotte, de voyeuristische scènes in Montjouvain en het ‘onfatsoenlijke’ gebaar dat Gilberte, de dochter van Swann naar Marcel maakt, zijn enkele van de verwachte etappes. En wat gebeurt er met de beroemde madeleine die het herinneringsproces aanzwengelt?

We kunnen concluderen dat de beweging die gepaard gaat met het opkomen van de herinneringen de mogelijkheden van het beeldverhaal uitbuit. Wanneer het stripverhaal allereerst horizontaal en via sequenties voortgaat, is er toch ook sprake van een belangrijke verticale beweging: men ‘leest’ de pagina van boven naar beneden; maar deze verticale dimensie kan ook anderszins worden geëxploiteerd om dieptewerking te bereiken. Malcolm Bowy toont aan dat de verticaliteit behalve zijn rol als antropologische en mythologische dimensie in de 19e eeuw ook zijn beslag krijgt in de paradigma’s van de toenmalige wetenschap (archeologie, historiografie, filosofie). Deze invulling van de verticaliteit valt ook overal bij Proust terug te vinden.

Sleutelmomenten zijn bijvoorbeeld de beschrijving van de klokkentoren van Combray, het aanbreken van de dag, het naar boven gaan naar de slaapkamer of het afdalen in onderaardse ruimtes. Een moment dat bij uitstek met verticaliteit verbonden wordt is wanneer de herinneringen ‘opstijgen’. Het stripverhaal kan op eigen wijze deze verticaliteit vormgeven. Bij Heuet treft men diverse voorbeelden aan van deze plastische dimensie: het naar boven gaan als inleiding op het drama van het naar bed gaan (13); de beelden van de kerktoren (22), het afdalen in de crypte (21) of het kijken naar de regen van boven af. Vaak zijn het panorama-achtige gezichten, van boven gezien, die de verticaliteit aangeven: bijvoorbeeld op pagina 5 waar de familie van bovenaf wordt gezien als hechte eenheid of wanneer de besloten wereld van het dorpje uit de hoogte wordt bekeken (45).

Bij de madeleine-scène wordt de materialisatie van het verleden ook zo vorm gegeven. Op pagina 14 herkennen we de winters aangeklede figuur van de voorpagina die zo aankondigt dat er iets belangrijks gaat komen. Hij gaat bij ‘maman’ naar binnen en krijgt zijn thee met koekie. Van het lepeltje dat in de lucht lijkt te zweven beginnen weldoende dampen op te stijgen, terwijl de werkelijkheid van de theepot vervaagt en de tekst de ruimte gaat opeisen. Het afdalen langs de pagina wordt uiteindelijk omgedraaid omdat het laatste plaatje boven naar de volgende pagina ‘reist’ op het geurende wolkje dat dan overgaat in de haarlok van de extatische genieter.

De bijbehorende monoloog slingert zich over het gezicht via de plooien van de wangen en het voorhoofd. Het recitatief dat boven aan de pagina begint met de woorden “wat diep in mij klopt” eindigt vreemd genoeg beneden aan de bladzijde als volgt “zal de herinnering tot aan het oppervlak van mijn heldere bewustzijn kunnen komen?” Men bemerkt dat de opeenvolging van de tekst en de iconische verticaliteit met elkaar rivaliseren. Dat is een epistemologische en een ideogische rivaliteit, maar vooral hun technische en materiële weerslag. Het modernisme weerspiegelt immers allereerst de historische en wetenschappelijke overgang tussen verticale (theo-teleologische) systemen en horizontale (technisch-immanentistische) modellen. Dan kunnen we de pagina wel omslaan om een eerste plaatje te ontdekken dat zich over de volle hoogte van de pagina uitstrekt: via tafellaken, theepot, kop, Marcel in trance, slierten geurige theedampen en opnieuw de tekst “Dag tante Léonie”, komen we bij een goudkleurige hemel aan die dus niet naar buiten verwijst maar naar het universum van de tekst.

Na een stuk tekst komen we dan op een volle pagina die het dorp toont in een sprookjesdecor, met meidoorn en waterlelies omzoomd, en waar een krans van huizen de Sint Hilarius kerk omringt. De verbinding wordt expliciet gelegd door wolkenbanden die vanuit de kop van de pagina afkomstig zijn. Het recitatief staat als een soort wettekst boven het idyllische beeld van het dorpje en de pseudo-tekstbellen die opstijgen vanuit de theekop profiteren van de open ruimte en zeilen gracieus naar de wolken met als belofte het vervolg van het verhaal. Het dorp ademt met dit beeld harmonie, eenheid en geborgenheid uit. Eenzelfde soort geluksstemming gaat uit van pagina 27 waar een stralende Françoise een tafel vol lekker eten presenteert.

In À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs 1 wordt de ruimte breed uitgemeten. Vooral het Grand Hôtel in Balbec geeft de tekenaar de gelegenheid om uit te pakken. Op pagina 13 zien we hoe de grootse raampartij het strand domineert: van daarboven beheerst men de wereld! De dubbele pagina 20-21 maakt het mogelijk ‘s avonds rondom het grote gebouw te kijken, dan de eetzaal binnen te gaan met de gepriviligeerde gasten en vervolgens een meewarige blik te werpen op de dorpelingen die zich voor het grote raam aan hen vergapen. Het stripverhaal werkt met compartimenten en buit deze relatie uit. Zo bij het Grand Hôtel dat met zijn diverse locaties functioneert als draaischijf voor de opeenvolgende episodes en als ontmoetingsplaats voor de meest uiteenlopende personages. Voor Marcel is het hotel overigens allereerst een onbekende plaats waar zijn gewoontes hem wreed in de steek laten. Zijn kamer, doordrongen met de gehate geur van vetiver, bevindt zich op pagina 10 aan het eind van een angstaanjagend steile trap en slaat in al zijn enge beklemming op hol. Dan zien we de jongen van bovenaf in zijn bed liggen, verloren in een vijandig universum zonder houvast. De andere kant van deze dubbele pagina laat op specifieke wijze een contrasterend element naar voren komen zoals Proust die graag op zijn manier schetst. De volgende morgen gaat namelijk het raam open boven “de naakte zee” en de hele ruimte wordt dan gevuld met wind en wolken, rechtstreeks en ook in de ramen gespiegeld. Zee en land vermengen zich zoals in de schilderijen van Elstir en deze esthetische ervaring brengt redding. Heuet profiteert van de ruimte die de tekenaar ter beschikking staat, maar hij doet dit door tegenstellingen uit te werken (en niet door bijvoorbeeld een doolhof te creëren), en daarmee treedt hij resoluut in het voetspoor van de modernisten.

Een ander voorbeeld waar Heuet Proust imiteert treft men aan in het intermediale spel met de schilderkunst. Hij beeldt het portret van Zephora door Botticelli, waar de verliefde Swann zijn Odette in ziet, natuurgetrouw af en introduceert ook andere doeken in huize Swann; tegenover de striptekeningen fascineren deze ‘realistische’ schilderingen als echter dan echt, en dit geeft op wel heel bijzondere wijze een invulling aan het fetisjisme van Swann.

Liefde en kunst komen ook nog op andere manieren bij elkaar in het verhaal van Swann. Daarbij speelt vooral de sonate van de componist Vinteuil een belangrijke rol als “volkslied” van de liefdesrelatie met Odette. Een dubbele pagina 18-19 biedt alle ruimte om de muziek visueel weer te geven. Het resultaat is meervoudig gelaagd: tekstcitaten, beelden van de luisterende Swann en een achtergrond met een meer in de bergen alsmede een rozentuin met drie verlichte ramen daarachter, vormen een collage van boven en tussen elkaar geprojecteerde lagen. Aan de bovenkant van dat landschap hangen linten met muzieknoten erop die zweven als een bruidssluier. Nog verder daarboven bevinden zich de twee muziekinstrumenten (viool en piano). Aan twee zijden gaan de muziekbalken even over het kader heen en zorgen zo voor een soort continuïteit die harmonieert met de aandacht van Proust voor esthetische fluïditeit welke ook het levende water van het meer weergeeft. De artistieke synesthesie die hier oplicht verwijst naar het belang van dit motief in de Recherche, nauw verbonden met de autonomie van het kunstwerk.

Ook in de episode rond de “catleyas” gaat het om de visualisatie van de gevoelens van Swann in een soort vreugde-explosie na een eerste periode van angst om Odette te verliezen (33). Een suggestieve passage gaat vooraf aan meer expliciete liefdesbetuigingen tijdens hun tocht per rijtuig door Parijs (waar men Emma Bovary op de achtergrond vermoedt). Het erotische gehalte van die beelden is nogal mager en het lijkt alsof de kunstenaar op zijn eigen manier hier wat aan heeft willen doen. Hij neemt eerst uitgebreid zijn toevlucht tot schetsen van Watteau waar Proust ook zijdelings gewag van maakt als hij ze vergelijkt met de uitdrukkingen op het gezicht van Odette wanneer ze lacht. Als uitdrukking van veranderlijkheid is deze visualisatie zeker interessant. Maar het beeld dat heel kenmerkend voor Heuet is en dat de serie afsluit beslaat vervolgens bijna de hele pagina 37. Odette ligt languit op de divan met rondom hoge boekenkasten vanwaar Swann op haar neerkijkt. Het is volstrekt duidelijk dat zij geen ‘boekenvrouw’ is, maar wel volledig een ‘vrouw uit een boek’. “À suivre” sluit dan de tekst van dit album af waar echter de voornaamste semantische keten eindigt met een laatste plaatje van een catleya waaruit in stippellijn naar de toekomst gerichte geuren opstijgen.

De hechte structuur en de frequente verwijzingen naar de eigen kunstvorm geven een uitermate modernistisch air aan deze creatie uit het universum van de stripverhalen dat vaker als laboratorium voor postmoderne tendensen kan worden aangemerkt.

Dat tenslotte deze strips niet alleen door Proustkenners op prijs worden gesteld, maar dat ze ook een commercieel succes zijn geworden, is natuurlijk te danken aan de faam van de brontekst en aan het vakmanschap van Heuet, maar wellicht dat de hang van het publiek naar modernistische (of retro-moderne) artisticiteit de doorslag heeft gegeven.

NOTEN

[i] Zie Houppermans, 1987.

[ii] Cf het beroemde portret van Proust door Jacques-Émile Blanche.

[iii] Ik verwijs naar de Pléiade-editie van de Recherche uitgegeven Jean-Yves Tadié (Parijs, 1987); vertalingen uit het Frans in dit artikel zijn van mijn hand.

[iv]De ‘petite madeleine’ is de geurige gangmaker bij uitstek op het pad der herinneringen; maar Proust schrijft Madeleine met hoofdletter en naast andere associaties kan men dan denken aan het bijbelse geuroffer van Marie- Madeleine (Maria Magdalena).

[v] Zie Houppermans, 2007.

Bibliografie

Bowie, Malcolm, Freud, Proust and Lacan, Theory as Fiction, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Brakman, Willem, Vrij uitzicht, Amsterdam, Querido, 2001.

Gobin, Marie-Hélène, Proust et la bd? Que dira Baudelaire ; étude sémiotique, Éditions Connaissances et Savoirs, 2006.

Groensteen, Thierry, Système de la bande dessinée, Paris, PUF, 1999.

Houppermans, Sjef, “Subject en intertekst” in Spiegel der Letteren, no 1-2, Leuven, 1987, 43-52.

Houppermans, Sjef, Marcel Proust constructiviste, Amsterdam, Rodopi, 2007.

Koenig, Gaspard, Octave avait 20 ans, Paris, Grasset, 2004.

Proust, Marcel, A la recherche du temps perdu, 4 delen, Paris, Gallimard, 1987 (la Pléiade).

Heuet, Stéphane Stripversie van de Recherche, 5 delen verschenen, Paris, Delcourt, 1998-2008 (Nederlandse vertaling bij uitgeverij Atlas).

Dit essay is verschenen in de bundel:

Rozenberg 2010 – 978 90 3610 214 8