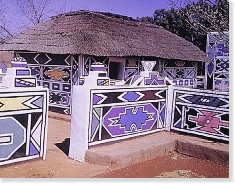

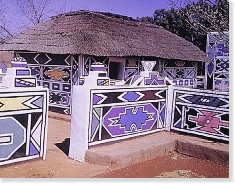

Ndebele home

12-05-2015 ~ With an Introduction by Milton Keynes

The Ndebele of Zimbabwe, who today constitute about twenty percent of the population of the country, have a very rich and heroic history. It is partly this rich history that constitutes a resource that reinforces their memories and sense of a particularistic identity and distinctive nation within a predominantly Shona speaking country. It is also partly later developments ranging from the colonial violence of 1893-4 and 1896-7 (Imfazo 1 and Imfazo 2); Ndebele evictions from their land under the direction of the Rhodesian colonial settler state; recurring droughts in Matabeleland; ethnic forms taken by Zimbabwean nationalism; urban events happening around the city of Bulawayo; the state-orchestrated and ethnicised violence of the 1980s targeting the Ndebele community, which became known as Gukurahundi; and other factors like perceptions and realities of frustrated economic development in Matabeleland together with ever-present threats of repetition of Gukurahundi-style violence—that have contributed to the shaping and re-shaping of Ndebele identity within Zimbabwe.

The Ndebele history is traced from the Ndwandwe of Zwide and the Zulu of Shaka. The story of how the Ndebele ended up in Zimbabwe is explained in terms of the impact of the Mfecane—a nineteenth century revolution marked by the collapse of the earlier political formations of Mthethwa, Ndwandwe, and Ngwane kingdoms replaced by new ones of the Zulu under Shaka, the Sotho under Moshweshwe, and others built out of Mfecane refugees and asylum seekers. The revolution was also characterized by violence and migration that saw some Nguni and Sotho communities burst asunder and fragmenting into fleeing groups such as the Ndebele under Mzilikazi Khumalo, the Kololo under Sebetwane, the Shangaans under Soshangane, the Ngoni under Zwangendaba, and the Swazi under Queen Nyamazana. Out of these migrations emerged new political formations like the Ndebele state, that eventually inscribed itself by a combination of coercion and persuasion in the southwestern part of the Zimbabwean plateau in 1839-1840. The migration and eventual settlement of the Ndebele in Zimbabwe is also part of the historical drama that became intertwined with another dramatic event of the migration of the Boers from Cape Colony into the interior in what is generally referred to as the Great Trek, that began in 1835. It was military clashes with the Boers that forced Mzilikazi and his followers to migrate across the Limpopo River into Zimbabwe.

As a result of the Ndebele community’s dramatic history of nation construction, their association with such groups as the Zulu of South Africa renowned for their military prowess, their heroic migration across the Limpopo, their foundation of a nation out of Nguni, Sotho, Tswana, Kalanga, Rozvi and ‘Shona’ groups, and their practice of raiding that they attracted enormous interest from early white travellers, missionaries and early anthropologists. This interest in the life and history of the Ndebele produced different representations, ranging from the Ndebele as an indomitable ‘martial tribe’ ranking alongside the Zulu, Maasai and Kikuyu, who also attracted the attention of early white literary observers, as ‘warriors’ and militaristic groups. This resulted in a combination of exoticisation and demonization that culminated in the Ndebele earning many labels such as ‘bloodthirsty destroyers’ and ‘noble savages’ within Western colonial images of Africa.

Ndebele History

Ndebele History

With the passage of time, the Ndebele themselves played up to some of the earlier characterizations as they sought to build a particular identity within an environment in which they were surrounded by numerically superior ‘Shona’ communities. The warrior identity suited Ndebele hegemonic ideologies. Their Shona neighbours also contributed to the image of the Ndebele as the militaristic and aggressive ‘other’. Within this discourse, the Shona portrayed themselves as victims of Ndebele raiders who constantly went away with their livestock and women—disrupting their otherwise orderly and peaceful lives. A mythology thus permeates the whole spectrum of Ndebele history, fed by distortions and exaggerations of Ndebele military prowess, the nature of Ndebele governance institutions, and the general way of life.

My interest is primarily in unpacking and exploding the mythology within Ndebele historiography while at the same time making new sense of Ndebele hegemonic ideologies. My intention is to inform the broader debate on pre-colonial African systems of governance, the conduct of politics, social control, and conceptions of human security. Therefore, the book The Ndebele Nation (see: below) delves deeper into questions of how Ndebele power was constructed, how it was institutionalized and broadcast across people of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. These issues are examined across the pre-colonial times up to the mid-twentieth century, a time when power resided with the early Rhodesian colonial state. I touch lightly on the question of whether the violent transition from an Ndebele hegemony to a Rhodesia settler colonial hegemony was in reality a transition from one flawed and coercive regime to another. Broadly speaking this book is an intellectual enterprise in understanding political and social dynamics that made pre-colonial Ndebele states tick; in particular, how power and authority were broadcast and exercised, including the nature of state-society relations.

What emerges from the book is that while the pre-colonial Ndebele state began as an imposition on society of Khumalo and Zansi hegemony, the state simultaneously pursued peaceful and ideological ways of winning the consent of the governed. This became the impetus for the constant and ongoing drive for ‘democratization,’ so as contain and displace the destructive centripetal forces of rebellion and subversion. Within the Ndebele state, power was constructed around a small Khumalo clan ruling in alliance with some dominant Nguni (Zansi) houses over a heterogeneous nation on the Zimbabwean plateau. The key question is how this small Khumalo group in alliance with the Zansi managed to extend their power across a majority of people of non-Nguni stock. Earlier historians over-emphasized military coercion as though violence was ever enough as a pillar of nation-building. In this book I delve deeper into a historical interrogation of key dynamics of state formation and nation-building, hegemony construction and inscription, the style of governance, the creation of human rights spaces and openings, and human security provision, in search of those attributes that made the Ndebele state tick and made it survive until it was destroyed by the violent forces of Rhodesian settler colonialism.

The book takes a broad revisionist approach involving systematic revisiting of earlier scholarly works on the Ndebele experiences in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and critiquing them. A critical eye is cast on interpretation and making sense of key Ndebele political and social concepts and ideas that do not clearly emerge in existing literature. Throughout the book, the Ndebele historical experiences are consistently discussed in relation to a broad range of historiography and critical social theories of hegemony and human rights, and post-colonial discourses are used as tools of analysis.

Empirically and thematically, the book focuses on the complex historical processes involving the destruction of the autonomy of the decentralized Khumalo clans, their dispersal from their coastal homes in Nguniland, and the construction of Khumalo hegemony that happened in tandem with the formation of the Ndebele state in the midst of the Mfecane revolution. It further delves deeper into the examination of the expansion and maturing of the Ndebele State into a heterogeneous settled nation north of the Limpopo River. The colonial encounter with the Ndebele state dating back to the 1860s culminating in the imperialist violence of the 1890s and the subsequent colonization of the Ndebele in 1897 is also subjected to consistent analysis in this book.

What is evident is that the broad spectrum of Ndebele history was shot through with complex ambiguities and contradictions that have so far not been subjected to serious scholarly analysis. These ambiguities include tendencies and practices of domination versus resistance as the Ndebele rebelled against both pre-colonial African despots like Zwide and Shaka as well as against Rhodesian settler colonial conquest. The Ndebele fought to achieve domination, material security, political autonomy, cultural and political independence, social justice, human dignity, and tolerant governance even within their state in the face of a hegemonic Ndebele ruling elite that sought to maintain its political dominance and material privileges through a delicate combination of patronage, accountability, exploitation, and limited coercion.

The overarching analytical perspective is centred on the problem of the relation between coercion and consent during different phases of Ndebele history up to their encounter with colonialism. Major shifts from clan to state, migration to settlement, and single ethnic group to multi-ethnic society are systematically analyzed with the intention of revealing the concealed contradictions, conflict, tension, and social cleavages that permitted conquest, desertions, raiding, assimilation, domination, and exploitation, as well as social security, communalism, and tolerance. These ideologies, practices and values combined and co-existed uneasily, periodically and tendentiously within the Ndebele society. They were articulated in varied and changing idioms, languages and cultural traditions, and underpinned by complex institutions.

Cecil John Rhodes

The book also demonstrates how the Ndebele cherished their cultural and political independence to the extent of responding violently to equally violent imperialist forces which were intolerant of their sovereignty and cultural autonomy. The fossilisation of tensions between the Ndebele and agents of Western modernity revolved around notions of rights, modes of worshiping God (religion and spirituality), concepts of social status, contestations over gender relations, and general Ndebele modes of political rule. Within the Ndebele state religious, political, judiciary and economic powers were embodied within the kingship, and the Christian missionaries wanted to separate the spiritual/religious power from the political power. This threatened Ndebele hegemony and was inevitably resisted by the Ndebele kingship. In the end, the British imperialists together with their local agents like Cecil John Rhodes, Charles Rudd, John Smith Moffat, Charles Helm and many others, reached a consensus to use open violence on the Ndebele state so as to destroy it and replace it with a colonial state amenable to Western interests and Christian religion. The invasion, conquest and colonisation of the Ndebele became a tale of unprovoked violence and looting of Ndebele material wealth, particularly cattle, in the period 1893 to1897.

The book ends by grappling with some of the complex ambiguities and contradictions of the colonial encounter and the equally ambiguous Ndebele reactions to early colonial rule during the first quarter of the twentieth century. Thus, from a longer-term perspective, the issues raised in this book have important resonance with current concerns around nation building, power construction, democratization, sovereignty, legitimacy, and violence in Africa in general and Zimbabwe in particular.

Milton Keynes, United Kingdom, February 2008

Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni

Hegemony, Memroy and Historiography

Our kings were sympathetic to their subjects. They tried to ensure happiness for their people. A hungry person is a disgrace in any kingdom… Today leaders never come out to hear voices of their people so that they can know how they are living. Our government is not like it was in the kingdoms of Lobengula, Mzilikazi, and Shaka. Chiefs had power then to say and change the lives of their subjects.

There is an indigenous philosophy deeply embedded in, and inextricably woven with, our culture [which] radiates and permeates through all facets of our lives… It is not necessary for Africans to swallow holus bolus foreign ideologies…It is the duty of African scholars to discern and delineate African solutions to African problems.

If an African statesman concludes today that the wind of democracy is now blowing through Africa, he must be referring to the wind of European democracy. For Africa developed its own democratic principles, yet these were never recognised as such by Europeans or by Africans educated in Europe.

One of the problematic arguments in African studies is that which views nations, nationalism, good governance, democracy and human rights as phenomena that Western societies invented and that African societies were incapable of inventing. This argument has created a pervasive belief of the West as a zone of ‘haves’ and Africa as the zone of ‘have nots’ not only in material terms but also in terms of positive history, positive ideologies, progressive human practices and other human inventions like nations. As noted by Ramon Grosfoguel, this is an epistemic strategy crucial for sustenance of Western hegemony, and its genealogy and development has taken the following trajectory:

We went from the sixteenth century characterisation of ‘people without writing’ to the eighteenth and nineteenth century characterisation of ‘people without history,’ to the twentieth century characterisation of ‘people without development’ and more recently, to the twenty-first century of ‘people without democracy’. We went from the sixteenth century ‘rights of people’… to the eighteenth century ‘rights of man’ … and to the late twentieth century ‘human rights’.

The net effect of this trajectory on African scholarship is timidity when it comes to discerning such phenomena as nations, human rights, and democracy organic to African history and African experiences. This book challenges such timidity as it makes sense of the key ideological contours of the Ndebele nation and its notions of democracy and human rights.

The Ndebele were a formidable nation in the nineteenth century, with unique institutions of governance, distinct political ideologies, and a worldview that was shaped by their specific historical experiences. The Ndebele nation was a multinational one comprised of Nguni, Sotho, Tswana, Kalanga, Shona, Venda and Tonga ethnic groups. The national language was IsiNdebele. Its founding father was Mzilikazi Khumalo, a charismatic leader and a competent nation-builder.

Pre-colonial nations such as this were not products of ‘modernity’ in the sense of the word as it is used by modernists like Eric J. Hobsbawn, Ernest Gellner and Benedict Anderson. It was a product of what John Omer-Cooper described as a ‘Revolution in Bantu Africa,’ and chapter two of this book provides details of this revolution. What emerged from this revolution as an Ndebele social formation was characterised by a far more self-conscious spirit of community that transcended a parochial ethnicity. Many ethnicities coalesced in the constitution of the nation to create an Ndebele political identity that unified the people under one leader.

The Ndebele nation is one of the most misunderstood polities in Africa. It was described as a unique social formation underwritten and underpinned by a militaristic state. Its government was represented as autocratic and barbaric with all its activities revolving around raiding of its neighbours. To the early missionaries it was an abomination that needed destruction as it stood in the way of Christianity, Civilisation and Commerce. Like many other pre-colonial political formations, it was sometimes described as a ‘kingdom,’ or a ‘chiefdom,’ or even a ‘tribe’.

The book challenges some of these representations of the Ndebele nation and provides a new understanding of the institutional and organisational set-up of this pre-colonial nation, revealing and making sense of key ideologies that sustained it. The story starts off with explorations of how Mzilikazi Khumalo was able to build a nation out of people of different ethnic backgrounds and why he was successful in constructing a particular national identity out of people of different ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds that still endures today in Matabeleland and the Midlands regions of Zimbabwe.

The book makes a direct contribution to studies of pre-colonial systems of governance, pre-colonial notions of democracy and human rights, that have remained prisoner to mythologies, stereotypes, colonisation and romanticisations. There is a major challenge in studies like this one focusing on interrogation of pre-colonial systems of governance and deciphering pre-colonial practices of rights, entitlements and demands that can collectively give us a picture of notions of democracy and human rights. The key challenge is imposed by sources of information. Colonial archives keep mainly those written documents created by colonial officials whose agenda was to deny the existence of orderly government, let alone democracy and human rights, in pre-colonial Africa.

The other challenge is that of reluctance by non-Africans as well as some Africans to recognise that African pre-colonial people, just like people elsewhere in the world, were capable of building nations, of constructing orderly governments and creating democratic and human rights space for their people. We need to critically engage those scholars who presented pre-colonial Africa as dominated by ‘martial tribes’ with their ‘warrior traditions’ always out to harm others, to steal cattle and women and to enslave those communities that were weak and vulnerable.

Achille Mbembe

Amudou-Mahtar M’bow, the Director of the United Nations Education and Scientific Council (UNESCO) from 1947-1987 wrote that all kinds of myths and prejudices concealed the real, key contours of African life and institutions. Achille Mbembe, a respected African scholar and brilliant postcolonial theorist, added that:

The upshot is that while we now feel we know nearly everything that African societies and economies are not, we still know absolutely nothing about what they actually are.

This ignorance has given birth to an ‘African exceptionalism’ paradigm of various hues, within which everything in Africa is found to be weird and incomprehensible if compared with other parts of the world. This ‘African exceptionalism’ thinking is partly fed by the fact that despite numerous burials of the body of prejudices about Africa and Africans, ‘the corpse obstinately persists in getting up again every time it is buried and, year in and year out, everyday language and much ostensibly scholarly writing remain largely in thrall to this presupposition’.

Mbembe noted that writing and speaking rationally about Africa ‘is not something that has ever come naturally’. The ‘African human experience constantly appears in the discourse of our time as an experience that can only be understood through a negative interpretation. Africa is never seen as possessing things and attributes properly part of ‘human nature’. However, some scholars like Alex Thompson began to study Africans and their politics from a positive perspective with a view to making sense of all of the types of behaviour manifested and the character of the institutions built. To him:

Africans are innately no more violent, no more corrupt, no more greedy and no more stupid than any other human beings that populate the planet. They are no less capable of governing themselves. Not to believe this is to revive the racism that underpinned the ethos of slavery and colonialism. In this sense, African political structures are as rational as any other system of government. If there have been more military coups in Africa than in the United States, then there has to be a reason for this. An explanation also exists for why the continent’s political systems are more susceptible to corruption than those of the United Kingdom. By applying reason, the worst excesses of African politics (the dictators and the civil wars) can be accounted for, as can the more common, more mundane, day-to-day features of conflict resolution on the continent.

Indeed an understanding of the African condition today is never complete without digging deeper into the remote history of the continent and its people. Just like all other people elsewhere, Africans created durable states and ceaselessly struggled to create stable nations and to construct democratic modes of rule and governance. Within African societies there was dynamic social and cultural life besides military engagements. Historically grounded approaches are very useful in discerning and delineating those ideologies and those principles that made pre-colonial societies work. Dialo Diop has said clearly that ‘some historical depth is a prerequisite… and is indispensable if any prediction about Africa’s possible future… is to be made’.

Africa is today toying with the ‘African Renaissance’ as the nodal point around which African unity and development could be achieved. The philosophy of an ‘African Renaissance’ foregrounds African history as a resource through which positive values could be discerned and delineated – values that are useful for a new and positive re-imagination of the African continent and the identities of its people. This cannot be achieved without African historians engaging in nuanced and critical interrogations of the continents’ past with a view to recovering those values desperately needed for the self-definition of Africans and the re-centring of the continent within global politics.

The agenda of the ‘African Renaissance’ and its emphasis of discerning and delineating positive aspects of African history and African civilisation constitute a current broader context justifying the need for nuanced studies with a particular focus on pre-colonial societies like the Ndebele of Zimbabwe.

However, there is a danger in aligning historical studies and research too closely to politically driven agendas like the ‘African Renaissance’. The danger is that of ending up reviving the orthodox nationalist paradigm. This paradigm was in vogue in the 1960s and is well critiqued by Paul Tiyambe Zeleza, a brilliant African scholar and an able critic of nationalist historiography. According to Zeleza, nationalist scholarship shot itself in the foot. As he puts it:

Nationalist historiography has been too preoccupied with showing that Africa had produced organised polities, monarchies, and cities, just like Europe, to probe deeper into the historical realities of African material and social life before the advent of colonialism. As for the colonial period, nationalism was made so ‘over determining’ that only faint efforts were made to provide systematic, comprehensive, and penetrating analyses of imperialism, its changing forms, and their impact, not to mention the process of local class formation and class struggle. By ignoring these themes, nationalist historiography overstated its case: the overall framework in which the ‘heroic’ African ‘initiatives’ were as lost, and, in addition, African societies were homogenised into classless utopias.

Thus, nationalist historiography had failed to provide its own ‘problematic’ … it took over questions as they were posed by imperialist historiography: to the latter’s postulation of African backwardness and passivity, nationalist historiography counterpoised with notions of African genius and initiative.

I deploy critical analysis here to avoid this nationalist historiographical pitfall, and I take into account the complexities, contradictions, and ambiguities apparent within the evolution of Ndebele history to ensure that African pre-colonial past is not romanticised but critically examined. I engage here ‘disloyally’ even with those issues habitually ignored by nationalist historiography, such as forms of oppression and exploitation within the Ndebele state, as well as with the complex cleavages fashioned by local processes of ‘class’ formation and ‘class’ dualities, pitting the royals against the non-royals, and the Nguni stock against the captives, for instance. The historical realities of Ndebele material and social life before colonialism are subjected to critical social theoretical interrogation.

There would be no purpose in unpacking and exploding those notions created by early travellers, missionaries, explorers and colonial administrators only to replace them with nationalist-inspired notions that are equally problematic. A new historiography must transcend both. The intellectual endeavour is not to mythologize African realities, but to make new sense of them.

The other pre-occupation of this book is with forms of governance, human rights and democracy as manifested in pre-colonial and early colonial states. The World Bank has formulated a functionalist and instrumentalist definition of governance as:

… the traditions and institutions by which authority in a country is exercised for the common good. This includes (i) the process by which those in authority are selected, monitored and replaced, (ii) the capacity of the governments to effectively manage its resources and implement sound policies, and (iii) the respect of citizens and the state for the instruments that govern economic and social interactions among them.

This definition is cast in modernist and managerial terms but is useful across contexts and historical epochs, as governance is basically about management of public affairs—be it by pre-colonial, colonial, or post-colonial African leaders. Governance is about how power is configured and exercised within a polity. It is also about the issues of delivery or non-delivery of public goods by those in power to the governed. This is central to the accountability of the leadership to the governed. There are various ways of measuring this within the context of a pre-colonial polity. Chapter Three of this book provides details on the nature and dynamics of the Ndebele style of governance in the nineteenth century.

Colonial justifications for the imperial destruction of the Ndebele state in the late nineteenth century brought the discourse of human rights and democracy into the colonial discourses of cultural domination. In the first place, African pre-colonial societies in general and the Ndebele society in particular were said to be bereft of any traces of democracy and human rights. What was said to be at the centre of Ndebele governance was the notion of amandla (power). The exercise of this power manifested itself in the raiding of weaker polities and the enslavement of those who were unfortunate enough to be captured. Such colonial notions of Ndebele governance and politics cannot go unchallenged, as they distort the realities on the ground.

The colonial encounters could justifiably be described as a meeting of two hegemonic worlds with differing worldviews. At the centre of the contestations, the negotiations, the blending of peoples, the siphoning off and appropriations of the riches of the land, and even of the different readings of the meaning of the encounter, were issues of rights (individual and collective), entitlements and claims to certain things and certain commodities within the state. Western observers thought that human rights values and the capacity of individual to make choices were absent from and had to be introduced into Ndebele society. Here was a clear case of confusing the lack of a word or a close synonym for it with the lack of what it ultimately signifies. The Ndebele did not use the terms human rights and democracy as the missionaries used them, but they had notions of amalungelo abantu (rights, entitlements and claims of the people) which informed their society and their actions as they governed their state. I therefore introduce a theoretical discussion of human rights discourse in Chapter One of the book, after which I proceed to deal with rights, claims and entitlements in Chapters Three, Four, Five, Six and Seven.

The book reveals how early Christian missionaries tried to proselytise the Ndebele people into Christianity through preaching a gospel that emphasised issues of equality, accountability only to God, and other human rights principles as part of a new religious doctrine in the Ndebele state. In other words, it was the Christian missionaries who popularised the liberal-oriented ideologies of Christian civilization as an alternative to the assumed autocracy, barbarism and militarism of the Ndebele state. However, the behaviour of the early Rhodesian settler state, particularly its excessive violence, its militarism and its general disregard for Ndebele rights to land and to their cattle, revealed to the Ndebele the apparent lies and hypocrisy hidden within the professed ideology of Christian civilization and its human rights doctrines. These issues are detailed in chapter seven, where the emergence of what I term ‘Ndebele Christianity’ is discussed. It was indeed the despicable behaviour of the early colonial state that caused disillusionment among those Ndebele who had embraced Christianity and who were beginning to accept the professed ideologies of colonial civilization and commerce.

The Ndebele as a Nation

The theme that is dominant throughout this book is that of the Ndebele as a nation with its own ideologies and values of governance. But the questions of what is a ‘nation’ and when the nation began to exist have dominated the related debates on nationalism and identity.

To me the fashionable phrases dominant in mainstream discourse relating to the birth of nations and the rise of nationalism, such as the ‘invention of tradition,’ ‘imagined communities,’ and ‘constructed identities,’ are clearly intellectual endeavours to theorise the importance of human creativity in the foundation of nations and nation-states. Taken together, they express the important point that humanity throughout history has had the power to create its own preferred forms of associations, institutions and identities. They also allude to the creative power of the human mind and the centrality of human agency. But in the course of advancing the frontiers of this intellectual enterprise, the major theorists of the nation and nationalism faltered, as some began to deny this creative power to some civilisations and some people and assign it to some other civilizations and people.

This has generated heated debates. So far, the debates circulate around four key questions: the ‘what,’ ‘when,’ ‘why,’ and ‘how’ of nations and nationalism. In expanded form, in our context, the questions read: What is a nation? When does a nation come into being? Why was the particular nation created? How was the nation formed? The first question asks for the definition of the notion of a nation. The second asks for the provision of the date(s) and time frames of the formation of the particular nation. The third asks for the reason(s) behind the construction of the nation. The fourth asks for identification of the key paths/methodology/strategies of building the nation. The effort to answer these questions has produced four broad general paradigms: primordialism, constructivism, ethno-symbolism and instrumentalism, which are by no means monolithic bodies of thought and neat classifications of the numerous theorists. The key debate in this literature is whether the ‘nation’ and ‘nationalism’ are primordial phenomena or products of modernity. To primordialists, nations are seen as something intrinsic to human nature, as a type of social organisation that human beings need to form in order to survive. To primordialists nations existed in antiquity as well as in modernity. However, for modernists, nations and nationalism are a phenomenon of the modern era, where nationalism engendered and created nations. In between these two paradigms are ethno-symbolists who occupy the middle ground, accepting that although nationalism is a modern ideology, successful nations are built upon a pre-modern heritage. They also accept that nations could be found even before the onset of modernity.

Nations cannot be formed or constructed out of nothing. There is need for some foundation myth to anchor the nation. Where credible foundation myths were not found, innovative and creative nation-builders constructed these foundation myths alongside the actual construction of the nation. But what is a nation? Anthony D. Smith defined a nation as:

… a named and self-defined community whose members cultivate common myths, memories, symbols and values, processes and disseminate a distinctive public culture, reside in and identify with a historic homeland, and create and disseminate common laws and shared customs’.

Smith’s general idea is more useful than the modernists’ definition. Modernists defined a nation in terms of a well-defined territory with recognised borders; a unified legal system in accord with other institutions in a given territory; mass participation in social life by all members; a distinctive mass public culture disseminated through a system of standardised, mass public education; collective autonomy institutionalised in a sovereign state for a given nation; membership in an ‘inter-national’ system or community of nations; and legitimation by and through the ideology of nationalism. Smith’s definition is accommodative of those nations that existed prior to the modern age, although it does not fit all cases.

The western bias or orientation within these definitions reduces their power when they are applied to a pre-colonial African nation like that of the Ndebele. But, then, I do not believe that it is possible for any intellectual to come up with a ‘one-size-fits-all’ definition of nationhood. Different nations have emerged in different environments and across different historical epochs with different characteristics. Also a nation as an imagined phenomenon is perceived differently by different people, including the theorists of nation and nationalism.

What is useful here, in the current theoretical discussions of nationhood and nationalism is the grasp of the ‘constructed-ness’ of these phenomena. Even Smith, who is considered to be a primordialist cum ethno-symbolist, uses terms like ‘create’ and ‘disseminate’ in his definition, suggesting that he subscribes to the idea that a nation is a construction. Once the concept of the ‘constructed-ness’ of a nation is accepted then the issues of artificiality, malleability and fluidity and even the contingency aspect of nations like that of the Ndebele easily make sense.

In accounting for the construction of nations it is necessary to integrate both their historicity and contingency, but when the Hobsbawnian modernist school extended its interest to Africa in the 1980s it provoked an attempt by some scholars to see every African identity as a construction of colonialism. This happened as nationalist-inspired scholars attempted to trace the historical roots of tribalism and negative ethnicity. At the end of the day Europeans, missionaries, colonial officials and early anthropologists were given too much agency in the invention of tribes and ethnicities in Africa. African agency was almost denied by the early version of constructivism in shaping their identities prior to colonialism.

It took time for constructivists to realise their mistakes and for scholars like Terence Ranger to revisit their earlier propositions on ethnicity in Africa. Latter-day constructivists like Carolyn Hamilton and Bruce Berman revised and modified the thesis of colonial inventions of ethnicity, amending it in order to take into account pre-colonial antecedents which had nothing to do with the advent of colonialism. They accepted the idea of the existence of longer pre-colonial processes in which African people were active agents in the imagination and invention of their own identities. On this, Berman wrote that:

The invention of tradition and ethnic identities, along with polities, religions, trading networks and regional economies, were present in Africa long before the European proconsuls arrived to take control and attempt to integrate the continent more directly into the global economy of capitalist modernity.

The Ndebele nation is a typical example of a pre-colonially ‘constructed nation’. Prior to 1820, there was no Ndebele nation to talk of – not until Mzilikazi broke away from the Zulu kingdom to construct such an identity. Chapter Two of the book provides full details of the construction of the Ndebele nation. Memories of migration and offensive as well as defensive warfare in which the Ndebele took part either to replenish their numbers or to defend the nascent nation against other conquering groups later coalesced into the necessary myth of the foundation of the nation.

‘Ndebele-ness’ was a form of constructed citizenship that never stopped to be reconstructed across historical time. This is why there are numerous misunderstandings around who is an Ndebele. The discernible contours include those that reserve ‘Ndebele-ness’ to the royal Khumalo family or clan. This definition is of course too reductionist and clannish in that it does not take into account the snowballing of Ndebele identity over time and space. To some, Ndebele identity is confused with broader Nguni identity, which includes the Zulu, Xhosa, Shangaans, and Swazi. This is a form of Ngunization of Ndebele identity that is less meaningful to the specific use of the term after the Ndebele had settled in Zimbabwe. Terence Ranger saw this definition as exclusive, narrow and xenophobic.

At other times, being Ndebele is defined linguistically as one who speak Ndebele as a mother tongue. This is a linguistic definition. Yet at another level an Ndebele is defined as any person who resides in Matabeleland regions and those parts of the Midlands region where Ndebele is spoken. This is a regional-geographical definition. The important issue here is that the proliferation of these definitions indicates the contingency, malleability and fluidity of Ndebele identity across space and time, making it subject to different interpretations by even the Ndebele themselves.

The latest in this array of definitions of Ndebele identity is a very political one that emerged during the violence of the 1980s. An Ndebele was any person loyal to PF-ZAPU and Joshua Nkomo. This definition emerged within a politics that tried to ‘de-nationalise’ ZAPU and Nkomo in order to ‘provincialise’ and ‘tribalise’ Ndebele identity. ZANU-PF contributed greatly to the flourishing of this identity, when it openly stated that: ‘ZAPU is connected with dissidents and ZAPU is supported by the Ndebele, therefore Ndebele are dissidents’. Nkomo was presented as the modern king of the Ndebele and the ‘father of dissidents’ in this discourse. The Ndebele are neither a clan nor a tribe. In 1983, the ZANU-PF government made efforts to de-Ndebelecise the people of Tonga, Kalanga and Nambya stock in the midst of Fifth Brigade atrocities. Its propaganda was that in Binga, Jambezi and Hwange people had:

… particularly requested that the government should draw a clear distinction between them and the rest of Matabeleland. They did not want to be bothered in this talk of seceding Matabeleland [sic], emphasising that they did not belong to Zapu nor were they Nkomo’s people. They would like to have their own distinct province to be called Tonga-Nambya Province.

This propaganda strategy did not work, as ZAPU continued to enjoy support in these areas. Fifth Brigade persecutions of ZAPU supporters unintentionally brought Kalanga, Tonga, Venda, Sotho, Rozvi and Nguni close once again, in a solid Ndebele identity in opposition to Shona identity represented by the state and its violent army. Msindo observed that: ‘Zapu-ness seems to have become an engraved local political identity and constituted as part of being Ndebele so much that is was a “till death do us part” matter’.

Therefore it is no exaggeration to say the Ndebele are a nation which comprises all those people whose ancestors were incorporated into the Ndebele state in the nineteenth century. These include those of Nguni, Sotho, Shona, Kalanga, Tswana, Venda, Tonga and Rozvi extraction. This is the nation which Ndebele hegemony created. This is a historical-pluralistic and inclusive definition of being Ndebele. IsiNdebele is the common language spoken by the Ndebele, although such other languages as Kalanga, Venda and Sotho were spoken too and are still spoken alongside IsiNdebele. Despite colonial efforts to provincialise Ndebele identity and post-colonial efforts to ‘minoritise’ Ndebele identity, it has endured and weathered obstacles to its flourishing. Ndebele identity has emerged from the atrocities of Gukurahundi reinforced rather than diluted. ‘Minoritization’ of identities has always been intrinsically linked to struggles over socio-political power, cultural domination and control. ‘Minoritorization’ has no necessary factual basis in demography. It is an instrument constructed for use in pursuit of exclusionary political agendas.

Like all constructed identities, ‘Ndebele-ness’ remains prone to fluidity, malleability, reinforcement, contestations, acceptance and rejections. Msindo has uncovered a strong Kalanga ethnic consciousness in Matabeleland and is of the opinion that there is a widespread illusion ‘that Matabeleland is Ndebele land’ – an idea that deserves unpacking and explosion like all myths and illusions. This intervention, however, does not deny the historical reality that Nguni, Sotho, Shona and Kalanga groups subsisted within the Ndebele national identity throughout the existence of the Ndebele state under Mzilikazi and later under Lobengula.

The book therefore offers a nuanced, historically-grounded understanding of the existence of one of Africa’s nations. It provides a clear example of where clans and ethnic groups coalesced under a charismatic leader to become over time the heterogeneous Ndebele nation. The processes involved in the construction of the Ndebele nation were diverse and complex, including raiding, and more importantly strategic and delicate deployment of coercion and consent, in a typical hegemonic fashion.

The Ndebele as a minority group

Today, the Ndebele speaking people are part of a ‘unitary’ state called Zimbabwe, which is a creation of modern African nationalism. They form about twenty percent of the population of Zimbabwe. Their long and rich history is presently overshadowed by the triumphant Shona history that enjoys state support. The Shona speaking people make up about eighty percent of the Zimbabwean population. Besides constituting the dominant ‘ethnie,’ the Shona groups also consider themselves to be more indigenous to Zimbabwe than the Ndebele, who arrived in the area in 1839.

The name of the country is derived from Shona (Karanga) history. Ndebele history has nothing to do with the heritage site of Great Zimbabwe. The ruling elite are predominantly Shona. Feelings of exclusion and marginalisation among the Ndebele have reinforced a particularistic identity. However, it is important to note that the initial version of nationalism of the period 1957-1962 was inclusive of both Ndebele and Shona as oppressed Africans.

This led Msindo to argue that ethnic groups do not always stand as opponents to the development of a nation and that they sometimes complement efforts at developing an inclusive nation. Basing his analysis on ethnic-based societies, clubs and unions formed in Bulawayo, such as the Sons of Mashonaland Cultural Society, the Kalanga Cultural Society and the Matabele Patriotic Society, Msindo concluded that ethnicity and nationalism positively supported each other in the period 1950-1963.

It was during this period that ethnic associations produced nationalist leaders, and while ethnicity provided the required pre-colonial heroes and monuments the name ‘Zimbabwe’ was adopted by nationalist liberation movements for their imagined postcolonial nation. Leading nationalist political formations such as the Southern Rhodesia African National Congress (SRANC), the National Democratic Party (NDP) and the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) used ethnicity positively to mobilise the African masses. The ethnic cultural symbols used to this purpose included the traditional leopard skins worm by pre-colonial Shona and Ndebele chiefs and the Nguni hats worn by Ndebele chiefs, which early nationalist leaders like Nkomo, James Chikerema, George Nyandoro, Jaison Moyo and Leopold Takawira used to wear when addressing mass rallies. The ‘grand’ nationalist split of 1963 that saw the birth of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) as a splinter party from ZAPU initiated the negative mobilisation of ethnicity that characterized the whole of the liberation struggle period and beyond. The Ndebele-Kalanga group constituted the largest supporters of ZAPU until its demise in 1987, whereas ZANU was supported by the Shona groups. This evolution of nationalist politics in an ethnically bifurcated form had devastating implications for identities and nation-building within the postcolonial state. Within two years of independence the Shona-dominated state unleashed its military forces on the Ndebele, under the guise of flushing out some dissidents in Matabeleland and the Midlands regions of Zimbabwe. The ‘ethnic cleansing’ raged on from 1982 until 1987, claiming the lives of an estimated twenty-thousand Ndebele speakers. Bjorn Lingren has noted that one of the most serious and long-term consequences of the Gukurahundi atrocities has been to solidify the feeling of ‘Ndebele-ness’ among the people—’the people in Matabeleland accused Mugabe, the government and the “Shona” in general of killing the Ndebele’. Only with the Unity Accord of 22 December 1987 did the atrocities in Matabeleland and the Midlands regions come to an end. But the violence had already polarised the nation beyond repair.

The turn of the millennium saw the state of Zimbabwe shifting its attack to the minority white citizens. Earlier civic forms of nationalism that gave birth to the policy of reconciliation were quickly forgotten and the policy of reconciliation was repudiated. Brian Raftopoulos has noted that ‘a revived nationalism delivered in a particularly violent form, with race as the key trope within the discourse, and a selective rendition of the liberation history deployed as an ideological policing agent in the public debate,’ took centre stage in Zimbabwean politics at the beginning of the new millennium. In all of this, the question of who is a Zimbabwean gained new resonances and permeated the wider process of nation-building and re-imagination of the nation. All of this took place as Zimbabwe veered and plunged into unprecedented political and economic crisis.

Zimbabwe crisis and its historiography

The descent of Zimbabwe into an unprecedented crisis at the beginning of the Third Millennium has provoked new research into questions of nation-building, ideologies like nationalism, state-consolidation strategies and modes of rule, as the search for the roots of the crisis became the focus of political and policy analysis. The book, written at a time when Zimbabwe is undergoing one of its worst, multi-level and multi-layered crises engages with similar issues, but deals with a pre-colonial period leading up to the mid-colonial period.

The current crisis pervading Zimbabwe has elicited various interpretations that have yielded various descriptions of the nature of the meltdown. Scholars have competed to generate different epithets for the crisis, ranging from ‘state failure,’ ‘governance crisis,’ ‘exhaustion of patriarchal model of liberation,’ ‘malgovernance,’ and ‘unfinished business,’ to ‘economic crisis’. Indeed, by 2000 the state and its people found themselves on the edge, marked by serious governance deficits and humanitarian disasters as the state failed to deliver on every front. The crisis became so pervasive and devastating that it puzzled many an academic.

A historiography of the crisis has emerged that has a bearing on the current book. The first body of literature came from journalists with their propensity for instant analysis of grave situations and instant apportionment of blame for the crisis on particular political actors and institutions. Robert Mugabe, the President of Zimbabwe, was personally blamed for the crisis. The second body of literature came from political scientists with their deeper analysis of the murky present, with a view to prescribing the mysterious future. To some scholars, it was a ‘mutating millennial crisis,’ ‘generated by and generating particular ensembles of politics and practice related to at least three interweaving analytical themes and empirical arenas: the politics of land and resource distribution; reconstruction of nation and citizenship; and the making of state and modes of rule’.

Historians have not contributed directly to the historiography of the crisis save for one influential article and an edited volume by Terence Ranger. In the edited volume, Ranger directly explores a number of questions on nationalism, democracy and human rights, and makes the following useful observation:

But perhaps there was something inherent in nationalism itself, even before the wars and adoption of socialism, which gave rise to authoritarianism. Maybe nationalism’s emphasis on unity at all costs—its subordination of trade unions and churches and all other African organisations to its imperatives—gave rise to an intolerance of pluralism. Maybe nationalism’s glorification of leader gave rise to a post-colonial cult of personality. Maybe nationalism’s commitment to modernisation, whether socialist or not, inevitably implied a ‘commandist’ state.

Ranger was concerned to explain the failure of democracy in Zimbabwe and why this failure was attended by the transformation of the state into a militarised and intolerant leviathan. He put the blame at the door of the nature of Zimbabwean nationalism and its manifestations, which were not amenable to democracy and human rights.

In the article entitled Nationalist Historiography, Patriotic History and the History of the Nation: The Struggle over the Past in Zimbabwe, Ranger dealt with the historiographical implications of the crisis. He noted that:

There has arisen a new variety of historiography … This goes under the name of ‘patriotic history’. It is different from and more narrow than the old nationalist historiography, which celebrated aspiration and modernisation as well as resistance. It resents the ‘disloyal’ questions raised by historians of nationalism. It regards as irrelevant any history which is not political, and is explicitly antagonistic to academic historiography.

The subject matter of the book counters the current, dominant, state-sponsored narrative of ‘patriotic history’ and challenges the problematic mantra of ‘Zimbabweanism’ based on Shona hegemonies, where there is very little space for articulation of Ndebele hegemonies. The book deals with some of those ‘disloyal’ questions that are not in tandem with the dictates of ‘patriotic history’. In ‘patriotic history’ only race is a problem and ethnicity is never subjected to similar attention. One who raises issues related to ethnicity risks being ‘othered’ as unpatriotic. Venturing into research on Ndebele history is automatically considered to be an ‘unpatriotic’ exercise within state circles, as it is presumed to raise divisive ethnic problems and dirty histories not useful for nation-building imagined around the Great Zimbabwe heritage site.

The current debates on the crisis are clearly engaging with the issues of nation construction, the difficulties of forging common citizenship out of different racial and ethnic groups, the authoritarian methods of post-colonial state consolidation, and power-building. The study of the case of the formation and expansion of the Ndebele state into a nation reveals arts of nation-building that could be emulated, as well as negative tendencies that sound a warning to current African leadership in general and Zimbabwe in particular.

Based on his observations of how the leaders of Zimbabwe have struggled to build an enduring and stable nation since 1980, Eldred Masunungure wrote: ‘Nation-building, like state-building is a work of art and many African leaders have proved to be good state-building artists but poor nation-builders’.

Nation-building is not about exclusions. It is about inclusions. The Rhodesian state collapsed because it failed to build a nation. It used race as the criterion for excluding all black people from the enjoyment of civil and political rights. Are Zimbabwean leaders not repeating the same mistake by openly excluding whites as foreigners from the nation? What implications and signals does the exclusion of whites provide to such people as the Ndebele, who have not yet been fully integrated into the ‘Zimbabwe nation’ ? For how long will minorities be sacrificed at the altar of political expediency and majoritarian politics? Mahmood Mamdani argued that in many postcolonial African societies there is a general failure to transcend colonially crafted political identities to the extent that in engagement with citizenship issues, African regimes only turn the ‘colonial world upside down’. This marked by the fact that the ‘native’ now sits on top of the political world designed by the settler.

The civil war of 1982-1987 magnified and reflected the dangers associated with imagining a nation and state in terms of the vision of one ethnic group in the midst of a multiethnic society. If one ethnic group ascends to state power, as was the case with the Shona in 1980, do the other ethnic groups inevitably have to suffer exclusion and marginalisation? Even more dangerous, the ethnic group that had captured state power proceeded to use the state in violently dealing with Ndebele-speaking people. The ethnicised violence of the 1980s left an estimated twenty thousand Ndebele-speaking people dead. Ndebele-ism was under state-sanctioned attack. This Ndebele-ism was a form of nationalism that was considered to be antagonist to the form of nationalism popularised by the triumphant ZANU-PF around Shona languages, Shona history, Shona heroes and Shona symbols. The ZANU-PF-inspired nationalist idea was to make sure, by all available means including violence, that Ndebele identity was dead.

The civil war of 1982-1987 magnified and reflected the dangers associated with imagining a nation and state in terms of the vision of one ethnic group in the midst of a multiethnic society. If one ethnic group ascends to state power, as was the case with the Shona in 1980, do the other ethnic groups inevitably have to suffer exclusion and marginalisation? Even more dangerous, the ethnic group that had captured state power proceeded to use the state in violently dealing with Ndebele-speaking people. The ethnicised violence of the 1980s left an estimated twenty thousand Ndebele-speaking people dead. Ndebele-ism was under state-sanctioned attack. This Ndebele-ism was a form of nationalism that was considered to be antagonist to the form of nationalism popularised by the triumphant ZANU-PF around Shona languages, Shona history, Shona heroes and Shona symbols. The ZANU-PF-inspired nationalist idea was to make sure, by all available means including violence, that Ndebele identity was dead.

Up to now, the issue of the Ndebele identity in Zimbabwe remains a potential source of national tension in the country. In 2005, the Vice President of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), Gibson Sibanda, was quoted by the Daily Mirror as arguing that there was a need to re-build the Ndebele state along the lines of the single-tribe nations of Lesotho and Swaziland. He was quoted as saying ‘Ndebeles can only exercise sovereignty through creating their state like Lesotho, which is an independent state in South Africa, and it is not politically wrong to have the State of Matabeleland in Zimbabwe’.

Despite the fact that Sibanda later denied ever saying this, the statement encapsulates some emerging sentiments that are common among Ndebele-speakers in Zimbabwe. Since the achievement of independence in 1980, the Ndebele-speaking people have constantly been complaining of exclusion and marginalisation. A group of Ndebele-speaking people based in London calling itself the Mthwakazi People’s Congress (MPC) has openly called for the creation of a separate Ndebele state to be termed the United Mthwakazi Republic (UMR) comprising of the Matabeleland provinces and the Midlands. They noted that:

… for our part, for our present generation, this Zimbabwe, and any attempts to maintain it in any guise in future as a state that includes uMthwakazi, is as false as it is silly. It is only part of the grand illusion of the whole Zimbabwe project created in 1980. … What we have at the moment, courtesy of Robert Mugabe … is their Zimbabwe, of Shonas, and a fledging state for UMthwakazi which we have called UMR.

Moderate Ndebele politicians inside the country have also clamoured for a federal state within which Matabeleland would run its own political and economic affairs. All of these sentiments indicate the challenges of nation building in post-colonial Zimbabwe that need to be carefully historicised. The significant question is what lessons could post-colonial African leaders learn from pre-colonial leaders like Mzilikazi Khumalo, who created the Ndebele state in Zimbabwe?

Jeffrey Herbst has noted that African leaders across time and space have faced certain similar problems when trying to rule. The key problem was how to broadcast power and to build nation-states. Nation-building and governance remain major issues in post-colonial Africa and one wonders how pre-colonial leaders managed to build nations like that of the Ndebele, and what forms of governance kept the nation together. The choice of mode of rule is a central aspect of state-building and nation-building projects in Africa. The Ndebele state emerged and crystallised around a small Khumalo clan, and eventually matured into a heterogeneous nation incorporating different ethnic groups before its violent destruction by colonial forces in 1893 and 1896. This reality raises a number of relevant questions, which have been taken for granted for too long: How did one qualify to be a Ndebele? Was the Ndebele nation a civic nation or an ethnic nation? How was power configured in this nation? How accommodative was this state? How did the Ndebele elite deal with tensions of centralisation and decentralisation? How was power distributed? How did the ‘citizens’ access resources like land and cattle? How was coercion and consent balanced? These are indeed some of the key questions dealt with in this book.

Today the Ndebele suffer from both the perception and the reality of the marginalization of their past. They face the daily reality of playing second fiddle to the majority Shona ethnic group in the economy and in politics. They endure the daily reality of their history, their heroes, and their participation in the liberation struggle being consigned to a secondary role behind that of the triumphant Shona. That they were once a powerful, independent nation created out of migration, bloody wars, courage, resilience, and sacrifice is quickly losing its significance. The imagination, construction, and making of Zimbabwe in 1980 excluded the insights from Ndebele past. A cabinet minister and a historian, Stan Mudenge wrote that:

Present day Zimbabwe, therefore, is not merely a geographical expression created by imperialism during the nineteenth century. It is a reality that has existed for centuries, with a language, a culture and a ‘world view’ of its own, representing the inner core of the Shona historical experience. Today’s Zimbabwe is, for these reasons, therefore, a successor state. As successors to all that has gone before, present Zimbabweans have both materially and culturally, much to build and not little to build on.

The resilient Ndebele language, memory and history were negated in Zimbabwe, since they constituted a ‘sub-hegemonic’ wave in the midst of Shona ‘hegemony’. The Shona-dominated ruling elite in Zimbabwe felt that for purposes of nation-building, Ndebele history had to be forgotten – particularly the fact of Ndebele raids on the Shona polities. Ndebele history has therefore been silenced as the Ndebele themselves are written out of the Zimbabwe nation. This silence on Ndebele history led Jocelyn Alexander, Joan McGregor and Terence Ranger to write that:

We wanted to write about Matabeleland in part because silence has surrounded the history of this region of Zimbabwe. As we talked to the people in the districts of Nkayi and Lupane (into which the old Shangani Reserve was divided in the 1950s), we found that this silence had produced a profound sense of exclusion from national memory, and that idea of writing a history of Shangani inspired great enthusiasm.

One also needs to take into account that the sidelining of Ndebele historical experiences in the imagination of post-colonial Zimbabwe has to do partly with what Ray S. Roberts termed the ‘pervasive academic assumption of the centrality of nationalism in our history’. Zimbabwean nationalism has taken the form of majoritarian tyranny and majoritarian hegemonies crystallising in the form of what Roberts terms:

The Whiggish mould of Panglossian unilinear development—from enlargement-of-scale resistance in the 1890s, to modernising organisations of the 1940s, to radicalizing agitation in the 1950s-1960, to liberating chimurenga in the 1970s, and so unifying democracy from the 1980s: from religious-inspired unity from Matopos shrines in 1896-7 to Unity Accord negotiated in Harare in 1987—in short from Mkwati to Nkomo/Mugabe.

Throughout this continuum, Nkomo is a recent addition. Ndebele experiences are just an inconvenience that needed to be crushed if Shona triumphal history was to flow smoothly.

It is no wonder therefore that since 1976 when Julian Cobbing produced his doctoral thesis on Ndebele history no major study has been produced on the pre-colonial history of the Ndebele, as though Cobbing had answered all of the questions and addressed all of issues pertaining to Ndebele ideologies. Cobbing’s thesis was never revised into a book, and it remains known only to those in the academy.

On the other hand, the book broadly covers three broad phases of Ndebele historical experience, beginning with the period 1818 to 1842. This is the period of the Mfecane, migration, state formation, and the initial settlement of the Ndebele on the Zimbabwean plateau. The second phase is traced from 1842-1893. It is the period of settlement dominated by coalescence of various ethnic groups into a united and heterogeneous Ndebele nation, as well as the consolidation of Khumalo hegemony via the process of the ritualisation of kingship and the delicate balancing of coercion and consent.

The last phase is reconstructed from the first encounter between the Ndebele and the representatives of Western imperialism up to the mid-colonial period. It is the period of engagement with Christian missionaries, the British South Africa Company, conquest, and interactions between the Ndebele and the early Rhodesian colonial state, up to the mid twentieth century.

The significance of this study lies in its approach to the Ndebele past. It links together historical process, social practice, and cultural mediation in its reconstruction of the Ndebele history. In other words, this book goes beyond the existing increment of positivistic narratives that serve only to disguise the underlying structures of the Ndebele State. It moves away from the common approach confined to the realm of narration of events to the higher level of analysis situated in a scientific understanding of structure, social practice, and transformation.

As noted by Jean Comaroff, the socio-cultural structure and the ‘live-in’ world of practice are mutually constitutive: the former, because of the contradictory implications of its component principles and categories, is capable of giving rise to a range of possible outcomes on the ground. The world of practice, because of its inherent conflicts and constantly shifting material circumstances, is capable not only of reproducing the structural order, but also of changing it, either through cumulative shifts or by means of consciously motivated action. For instance, in the Ndebele state it was clear that the pre-colonial structural forms continued to be reproduced as long as the Khumalo leadership exercised control over the primary means of production and over those centralised institutions that underpinned the division of labour.

The approach of the book, therefore, entails a comprehensive re-consideration of Ndebele historical events as the practical embodiments of a more deep-seated structural order. In a way, one significant feature of the Ndebele historical events was to reflect the manner in which the Ndebele themselves struggled to reproduce their socio-cultural forms in different environments and circumstances. In short, the theoretical innovation of this book is predicated on the realisation that there is a need to take into account the interplay of subjects and objects, of the dominant and the subservient, and treat the social process as a dialectic process which is at once both semantic and material. Thus, this book suggests that it is the Ndebele historical experience itself which constitutes the basis for understanding the dialectic in which ideology ‘makes’ people and people ‘make’ ideology.

In its endeavour to unpack the complex interactions between the state and society and to unravel cultural practice and its attendant specificities, the book combines insights from the radical materialist approach to democracy and human rights with the powerful theory of hegemony elaborated by Antonio Gramsci. Gramsci’s theory is very useful in illuminating the history of society and of cultural practice and specifities.

The book is the first of its kind to delve deeply into the ideological intricacies of the Ndebele state with a view to teasing logical meaning out of what was sometimes dismissed as autocracy, militarism, superstition or barbarism. The book addresses very fundamental questions that have direct implications for the broader debates on governance and politics in Africa: How did the Khumalo establish hegemony? How did they manage to pass their values and ideas on to other members of the Ndebele society? How successful was the Ndebele ruling elite in making the Khumalo ancestors relevant for the consolidation, legitimacy, and dissemination of ideology? How did the Ndebele ruling elite manage conflicting interests within the Ndebele society? What strategies were used to gain support from the people who became part of the new Ndebele nation? What was the content and meaning of Ndebele oral literature? What was the nature of the relationship between the state and society among the Ndebele?

These are indeed fundamental questions whose answers are situated in a deeper reconstruction of the Ndebele history beyond the common narrative and ordinary ‘event history’. Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony is effectively employed to penetrate the body politic of the Ndebele state and society. Deploying this theory enabled this book to deal with such new questions as: How, precisely was Ndebele consciousness made and remade? How was it mediated by such distinctions as class, gender, age, and ethnicity? How did some meanings and actions, old and new alike, become conventional – either asserted as collective Ndebele values or just taken for granted – while others became objects of contest and resistance. How, indeed, are we to understand the connections, historically and conceptually, among culture, consciousness, and ideology in the Ndebele context?

These new questions have not been covered adequately in existing historical works on the Ndebele or for other African groups for that matter. Only the works of Tom McCaskie on the Asante in West Africa and Jan Vansina in Central and Equatorial Africa have grappled with these issues in these different geographical areas. Thus, in addition to addressing these issues, the book proceeds to tease meaning and logic out of the ambiguous and contradictory colonial encounter with the Ndebele. Grappling with the colonial encounter is very important in any study of Zimbabwe because of the way colonial and nationalist history has been appropriated by the ruling elite in contemporary political games and the emergence of what Terence Ranger terms ‘patriotic history’ with its simplistic rendition of both the colonial and the nationalist history of the country.

The book is divided into seven chapters where Gramci’s theory and insights from the democracy and human rights perspective are employed at various points, where and as they seem appropriate to deepen analysis. In Chapter One the main concern is with theoretical issues that underpin the whole book. It summarises Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, it defines the materialist conception of democracy and human rights, and spells out the criteria of human rights adopted in this book. The chapter also discusses the contours of the post-colonial theory that helps in the analysis of the complex dynamics of the colonial encounter and Ndebele responses to it. The chapter also contains a detailed historiography of the Ndebele past, starting with early missionary and settler accounts and proceeding up to the present work of Terence Ranger and Phathisa Nyathi.

Chapter Two is devoted to the formation of the Ndebele state and the emergence and construction of Khumalo hegemony in the midst of the Mfecane revolution. Attention is paid to the Khumalo group’s search for autonomy and how Mzilikazi Khumalo, here considered as a typical ‘traditional organic intellectual’ in the Gramscian sense, used the tactic of balancing coercion with consent to build his personal power base and to build the Ndebele state.

The complex processes that are teased out include migration as a tactic of preserving one’s autonomy and sovereignty in the face of the violent politics of the Mfecane and of powerful enemies. Migration is also viewed as a voluntary enterprise undertaken by ambitious personalities who sought to establish hegemony away from powerful states and powerful leaders. The Mfecane is defined and understood as a product of ambitious leaders’ hegemonic projects in their decisive phase. The main characteristic of this phase was the rise of new royal houses and clans that sought to challenge the status quo, and that sought to create personal power bases away from other powerful royal houses.

Zimbabwe

Chapter Three investigates the whole gamut of the constitution of a heterogeneous Ndebele nation that was by then permanently entrenched on the western part of the Zimbabwean plateau. The main focus is on how the Khumalo ruling elite was able to construct a durable though unstable hegemony over people of different ethnic groups, how they ceaselessly worked to forge alliances, and how they consistently attempted to convert sectarian ideas into universal truths. It was during this period that the Ndebele ruling elite worked very hard and succeeded to a great extent in capturing the popular mentality and imposing on the people the common conceptions of the world of the Ndebele nation and the form of governance that kept the people together.

This was achieved through various means, including a strategic shift from control by means of violence to control of the means of production, civilianisation of the main Ndebele institutions, strategic distribution of resources, full accommodation of non-Nguni groups, and – above all – ritualization of the kingship. In short, this chapter grapples and teases out the complex ideological matrix that constituted the Ndebele nation. These ideological contours included egalitarianism, clan and family intimacies, mutual assistance, welfarism and communalism, which co-existed with domination, exploitation, the violence of the leaders, insistence on seniority amounting to the entrenching of an aristocracy, authoritarianism and militaristic tendencies – all in turn underpinned by a strong patriarchal cast of mind and the all-embracing ideology of kinship.

Chapter Four takes the debate on governance further and is concerned with secular and religious control and domination exercised by the members of the ruling elite over their subjects during the settled phase of the Ndebele state. This chapter benefits much from insights from Antonio Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, and it is in this chapter that a considerable body of Ndebele oral literature is subjected to systematic analysis with a view to distil issues of democracy and human rights contained in them. The institution of amabutho is understood here as an ideological school that disseminated and reproduced Ndebele ideology. The annual inxwala ceremony is here presented as the centre of religio-politico and economic mingling and the renewal of the Ndebele nation, as well as the fundamental exercise in the continuous ritualisation of the kingship, with a view to constructing consent.

Chapter Five evaluates the initial encounter between European agents of colonialism and the Ndebele State. The focus is on the activities of Christian missionaries. The theoretical framework of this chapter is constructed from the ideas of Jean Comaroff and John L. Comaroff on the ambiguities of the colonial encounter with African societies in general. According to the Comaroffs, Christian missionaries were not only the vanguard of British colonialism, but were also the most active cultural agents of empire.

The Christian missionaries were driven by the explicit aim of reconstructing the African world in the name of God and European civilization. Unlike the mining magnates, who wanted minerals and the labour of the Africans, the Christian missionaries wanted the African soul. The whole missionary enterprise in Africa was an attempt to replace one form of hegemony with another, and this raised crucial clashes over norms, ideas and the general conception of the world while provoking resistance from the Africans.

Chapter Six is a critique of the colonial conquest of the Ndebele state and the general disregard of Ndebele economic and political rights. It highlights the violence of the imperialists and how the Ndebele tried to defend their sovereignty against the well-armed imperial forces that were intolerant of Ndebele independence. What is poignant in this chapter is how the imperialists looted Ndebele property, particularly cattle and land, in the process reducing the Ndebele to subjects of the colonial state.

Chapter Seven grapples with the crucial ambiguities and contradictions of the colonial encounter, as well as with the resonances of Ndebele memories of their past nation. The conceptual framework of this chapter is constructed from post-colonial theory as articulated by Homi Bhabha, Mahmood Mamdani and others. Mamdani’s theory about citizens and subjects in colonial societies helps to explain not only the denial of human rights and democracy to the Ndebele by the early Rhodesian colonial state, but also the ambiguous responses of the Ndebele to their domination and exploitation by a colonial regime.

On the other hand, Bhabha and Spivak emphasise that the colonised themselves have often played a significant role in colonial constructions of the ‘Other’.The chapter also benefits from the insights of the Comaroffs on the colonial encounter, which far transcend a simple paradigm of domination and resistance. Shula Marks’ idea of ambiguities of dependency also contributes to the unravelling of the colonial encounter and how the Ndebele contested and adapted to colonialism.

Chapter Eight constitutes the conclusion of this book. In it further meaning, the impact of and the long-term implications of the findings of this study are expressed and related to contemporary issues of governance, power, hegemony, memory and ideology in Africa in general and in Zimbabwe in particular.

—

Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni – The Ndebele Nation. Hegemony, Memory, Historiography

Rozenberg Publishers – ISBN 978 90 3610 136 3 (Europe only)

co-published with Unisa Press – ISBN 978 1 86888 565 7

www.unisa.ac.za