The Purchase Of The Farm Braklaagte By The Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa – Whose Land Is It Anyway? (1908-1935)

Braklaagte, registered as farm number 168 on the Transvaal farm register (the number was changed in the second half of the twentieth century to JP-90), was 3,152 morgen and 529 square rood in size, which is equal to 2,700.5441 ha in metric measurements.

The first title deed to the farm was registered in October 1874 in the name of Diederik Jacobus Coetzee. Ownership of the farm was transferred several times to other white farmers. W.M. Beverley was the last white owner before the farm was bought by the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa.

In 1906 a dispute arose in the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa tribe of Dinokana in Moiloa’s Reserve between Abraham Pogiso Moiloa and Israel Keobusitse Moiloa. When Abraham’s father, Ikalafeng, had died in 1893 he was a minor and Israel, Ikalafeng’s younger brother, would for a number of years act as regent. When Israel had to hand over the bokgosi (chieftainship) to Abraham in 1906 differences arose between them. A section of the tribe, led by Israel, moved eastward and settled at Leeuwfontein.

Already in 1876 Leeuwfontein had been bought for the tribe by chief Sebogodi Moiloa of Dinokana at the price of 200 head of large cattle, equivalent to about £1,000, but the transfer of the farm to the tribe had not yet been effected. ‘Quite an exodus’ of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa took place from Dinokana to Leeuwfontein and by 1907 the majority of Israel’s adherents had settled there.

After some time chief Abraham Moiloa visited Leeuwfontein in an attempt to persuade Israel’s followers to return to Dinokana to their old homes and lands. He promised to forget about the past, to forgive them and to treat them fairly. They refused to return to Dinokana without Israel and indicated that they regarded Leeuwfontein as their permanent village. Abraham then tried to solicit the help of the Native Affairs Department of the Transvaal Colony to evict Israel’s people from Leeuwfontein in terms of the Squatters Law, supposedly because they were defying any authority, but at first he was not successful. In 1908 he managed to get Israel and his brother Malebelele banished to the Heidelberg District of Transvaal, but they returned to Leeuwfontein in 1911.

Figure 2.1: Braklaagte and other surrounding farms mentioned in the book

In the few years between 1905, when the Transvaal Supreme Court made a ruling that temporarily lifted restrictions on individual black land ownership, and 1913, when the Natives Land Act once again restricted black land ownership, black people were able to purchase farms outside the reserves. After the breakaway section of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa had acquired a part of the farm Welverdiend and a part of Leeuwfontein, they tried to purchase the farm Braklaagte to the south of Leeuwfontein. It was a couple of years before the Union of South Africa came into existence and all hope of blacks to get a say in the central government of the country would be dashed.

On behalf of Pholoane Naone and Lesaroa Kgori a letter was directed to the Minister of Native Affairs of the Transvaal Colony in June 1908, in which they applied to purchase Braklaagte for £1,500 from its white owner. Initially the acting Secretary of Native Affairs replied that permission could not be granted, because the black buyers wanted to settle 64 persons there, which would amount to squatting. At that time the Minister had instructed native commissioners to put the Squatters Law into operation by identifying and evicting blacks in excess of the number allowed on farms outside the reserves. Eventually, however, authorisation was given for the purchase of the farm and in 1909 five men (Kgosimang, Lesaro Rakgori, Ramogapo, Pholoani Nauni and Radikoba), on behalf of their section of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa tribe, received their title deeds on the land. Thus Braklaagte was bought in undivided shares by a group of named black farmers, on behalf of a section of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa tribe. Because the government was unwilling to recognise the community as a separate tribe, they held the property under an undisclosed trust.

Sebetlela Ceremony

Israel Keobusitse Moiloa requested his brother Malebelele Sebogodi of the third house of kgosi Sebogodi to settle at Braklaagte and he became the headman and performed the sebetlela ceremony. Sebetlela is the ceremony performed when a traditional leader settles with his people at a new place. Four sticks are cut from a môrobê tree (Ehretia rigida subsp. Nervifolia, English popular name: puzzle bush), sharpened, treated by the traditional healer with special medicine and planted in the soil at the four corners of the land. It marks the land as belonging to that specific tribe, and the medicine should protect the people from danger.

Braklaagte was subordinate to Leeuwfontein. Just after the land had become the legal possession of the tribe, their struggle to hold on to it commenced. They took a mortgage on the purchase price of £1,500. This mortgage was repaid, amongst others, by deductions that the Zeerust native commissioner made from wages earned on the mines by Braklaagte residents. By 1913 they had fallen behind with the payments on the mortgage and they faced legal action, which could deprive them of the land. However, little by little the mortgage was repaid, and they managed to evade being put off the land for financial reasons.

The acquisition of the farms by Israel Moiloa’s section of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa occurred at a time when, according to revisionist historical studies, a transformation in labour and agrarian relations was taking place on the Transvaal Highveld because of capitalist development in South Africa. Processes of accumulation and dispossession resulted from the rise of mining and agricultural capital. Revisionists differ on the nature of the ‘uneasy’ alliance between ‘gold’ and ‘maize’, but agree that it led to the exploitation of cheap black labour and the impoverishment of the rural peasantry, both white and black. Mine owners and white commercial farmers needed workers and pushed for legislation that would give them easier access to African labour. Legislative measures to this effect were indeed adopted: access to land was made more difficult for black peasants, taxes and fees were raised, and stricter control over ‘squatting’ was introduced. The rural black peasantry, according to Bundy and other revisionist historians, was gradually deprived of the means to pursue an independent livelihood on the land. Whereas they initially managed to maintain their autonomy up to the end of the nineteenth century, their position vis-à-vis white commercial farmers and the white-controlled state rapidly deteriorated in the early twentieth century.

After the conclusion of the second Anglo-Boer War in 1902 black chiefs, who had supported the British war effort, including Bahurutshe chiefs, hoped to receive more land. However, this did not materialise and in the period of British colonial rule over the Transvaal a contrary process was taking place. Because of increasing labour demands by capitalist mining and agriculture rural Africans were increasingly being restricted to and even dispossessed of their tribal lands and incorporated into the capitalist economic system. Relationships of exploitation in the rural areas were changing. In the interior, Morris argues, rent paying tenants and sharecroppers increasingly found themselves impelled into labour tenancy. The next phase would be the conversion of labour tenants into wage labourers on white commercial farms.

In the Transvaal, where the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa lived, colonial control over land and labour was intensified during the post-war Milner period, which made it increasingly difficult for black peasants and tenants to produce food for the markets, and therefore to resist full dependence on wage earnings. In July 1907 the local sub-commissioner in the Native Affairs Department reported ‘a marked increase in the number of natives proceeding to Johannesburg in search of work’. During that month no fewer than 490 passes were issued to blacks in the Marico District.

Commercial agriculture was bolstered, which benefited Afrikaner landowners more than anyone else. The victory of the Het Volk party in the Transvaal elections of 1907 was based on their promise to restore white hegemony in the rural areas at the expense of African producers. Legislation against squatting, formerly applied rather patchily, was bound to be enforced more strictly. The Marico Farmers’ Co-operative in fact requested the government to assist farmers to apply the Squatters Law strictly.

In terms of the African agency discourse, mentioned in the introduction as one of the main threads of the Braklaagte narrative, it is clear that the purchase of farms outside the reserve by the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa was a deliberate action. These people exercised one of the few options available to them to get access to land. Thus they were resisting the processes of dispossession and proletarianisation that at that stage threatened to pin them down in an overcrowded reserve. The purchase of such farms in effect amounted to a means for black communities to extend the reserves. Their purpose was not to commercialise their farming and the newly acquired farms were immediately communalised.

Impact of the 1913 Natives Land Act

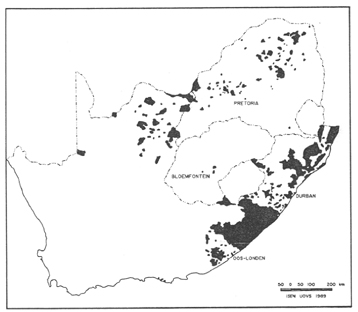

After the establishment of the Union of South Africa the political system accelerated the decline of the rural black peasantry. In 1913 the Natives Land Act was passed in parliament. The act reserved the shrinking areas under black communal control for occupation exclusively by blacks, but at the same time prohibited blacks from acquiring land outside the reserves. Scheduled land, that is, land set aside as reserves for black ownership in the schedule to the act, extended over about 9 million hectares or 7 per cent of all the land in South Africa. In addition the act attempted to curb squatting by blacks on white farms, by allowing them to stay on the farms only if they were employed there on a permanent or temporary basis.

The Natives Land Act was not the result of a desire to create the territorial basis of a just, if segregated, society. It was rather the response to the needs of white farmers, then the dominant interest group in South African politics, who required continued access to a supply of low-wage labour. It was intended to minimise competition for land by prohibiting blacks from acquiring land outside the reserves. In effect the 1913 act forced the majority of rural blacks, even formerly self-sustaining peasants, to work for someone else in order to be able to make a living. This was the case because the reserves were simply too small to provide a livelihood in agriculture for all their inhabitants. Therefore, the Natives Land Act is regarded as the death knell to the prosperity and possibilities of the peasantry. White commercial farmers only started acting in unity through farming associations towards the end of the 1920s. It took many years before the controls over sharecropping and squatting transformed labour relations into a pattern of labour tenancy. However, in the long run the population of the reserves became captive labour for the mines and the tenants became trapped labour for commercial farmers.

Figure 2.2: Scheduled lands in terms of the Natives Land Act, 1913. Moiloa’s Reserve was part of the scheduled lands, but Braklaagte was not.

Attempts to get the Braklaagte Title Deed transferred to the Minister

Although Braklaagte’s community was in a better position than most of the other rural communities, the ownership of Braklaagte was immediately at stake again when the 1913 Natives Land Act was passed. Private land ownership by blacks on land outside the areas reserved for them was restricted by the new legislation. The Bahurutshe of Braklaagte were in real danger of losing their claim to the land the moment the last of the five deed holders would die. To protect their tenure the black inhabitants of Braklaagte requested the local native commissioner in 1921 to transfer their title deeds to the Minister of Native Affairs, who would hold the deeds in trust for them as the rightful residents. At three different occasions F.S. Malan (Acting Minister of Native Affairs, 1915-1921), J.B.M. Hertzog (Prime Minister, 1924-1939 and also Minister of Native Affairs, 1924-1929) and E.G. Jansen (Minister of Native Affairs, 1929-1933) signed letters in which permission was granted for the transfer.

At that point in time the old feud between the Bahurutshe of Dinokana and the Bahurutshe of Braklaagte flared up again. During the 1920s and early 1930s the successive kgosi (chiefs) of Dinokana, Alfred Moiloa and Abraham Moiloa, were involved in disputes with the kgosana (headmen) of Braklaagte, Malabelele Sebogodi (Moiloa) and George Moiloa. Because the Department of Native Affairs did not want to make a precedent by recognising the section of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa which was settled at Leeuwfontein and Braklaagte as a separate tribe, they seemed in no particular hurry to comply with the request for the transfer of Braklaagte’s title deed to the minister. There had been an earlier Supreme Court ruling that a section of a tribe could not purchase land independently from the tribe of which it formed part. Consequently the transfer was delayed for more than a decade.

At this point the system of land tenure at Braklaagte was already moving away from true communal ownership under customary law to what Budlender and Latsky refer to as a system of ‘nationalised ownership’ held by the state. A few remarks need to be made here about the role of communal tenure and the situation of the black peasantry in the first half of the twentieth century.

Communal tenure, although it was originally based on African customary law, was modified by successive South African governments in the course of the twentieth century. Alternative forms of tenure were effectively denied to black people by law. In the literature communal tenure has been described as

… an essential component of the migrant labour system, facilitating the concentration of the maximum possible number of Africans in the reserves/homelands, preventing the emergence of a stratum of rich peasants or capitalist farmers and providing the basis for a high degree of social control through compliant tribal leaders who controlled access to land.

Formal title (in the form of deeds) of most communal land, including Braklaagte, was held by a state official on behalf of the state in trust for specific tribal communities and allocated by traditional leaders to people living under their jurisdiction on a usufructuary basis. Communal tenure was a hybrid form, which combined elements of individual and collective property rights. An individual’s right to use the land flowed from membership of a tribal community rather than from private ownership. However, communal tenure did not imply communal ownership of all resources and communal agricultural production. Allocated residential and arable plots were reserved for the exclusive use of the occupying household, and unallocated lands were available as a commonage, providing pasture for livestock. Those who were allocated land by the chief or headman obtained a right to the use and benefits of that land, but had no right to sell it. In effect communal tenure in twentieth-century South Africa meant ‘a degree of community control over who is allowed into the group, thereby qualifying for an allocation of land for residence and cropping, as well as rights of access to and use of the shared common pool resources used by the group (i.e. the commons)’.

Many South African social historians have argued that the native reserves were deliberately underdeveloped in order to force Africans to sell their labour to the farms, mines and factories of an industrialising South Africa. Colin Bundy contended that the African peasantry in the late 19th and early 20th centuries responded by increasing their production for the market. Then a rapid decline of the peasantry set in and by the 1930s an independent peasantry no longer existed. In his analysis of agricultural production Simkins came to the conclusion that the disintegration of the peasantry occurred a bit later, in the 1950s. Drummond states that available evidence from Dinokana would tend to support Simkins’s view. Agriculture in Dinokana seems to have remained stable and productive till at least the Second World War period and even into the 1950s. A range of agricultural products was produced at Dinokana and in the 1930s the community, regarded as a ‘model native area’, received a large grant from the Minister of Native Affairs for agricultural improvements. When the government completed an irrigation system during the drought of the early 1930s a local councillor expressed optimism that increased production would ensure a ‘great future’ for Dinokana.

One of the residents of Lehurutshe recalled:

Even when I was attending school before 1937 I was gardening all the time. Only a few were running gardens under irrigation. Most people were farming on dry land – kaffir corn and mealies. At that time we ploughed and irrigated wheat to a large extent. People were financially strong. I once harvested ninety bags of wheat, which I sold in Zeerust for Two Pounds Ten Shillings a bag. I sold vegetables locally as well.

In the case of Braklaagte it is not as easy to set a date for the decline of the peasantry, due to the lack of production data for the early twentieth century. Braklaagte was not as suitable for crop cultivation as Dinokana, because it did not have the same abundant water supply. Livestock farming was the main agricultural activity.

George Mosekaphofu Moiloa succeeded Malebelele Sebogodi after his death in 1925 as the headman at Braklaagte. He was the son of Israel Keobusitse Moiloa’s second wife, Mmamosweu. Because of family differences Israel had moved to Braklaagte, died there in 1923 and was buried in Malebelele’s cattle kraal. Mmamosweu and George Mosekaphofu stayed on at Braklaagte after his death. Malebelele’s rightful heir in terms of customary law, Lekoloane John Sebogodi, was only eleven years old when his father died. An ethnologist, Isaac Motile Selebego, gave evidence to the Mabiletsa Commission in the 1990s that Lekoloane had been banished to Barberton, but he did not state by whom and why he had been sent away. In terms of the later rivalry for the headmanship between the Sebogodis and the Moiloas it is important to note that George did not become headman in the customary way through a decision by the serobe (royal family council) and was never inaugurated in that position by the kgosi-tona (supreme chief). In reality he was acting on behalf of Lekoloane. However, he tried to strengthen his own hold on the position. He had the backing of the government, because the native commissioner recognised him as headman.

Although the government refused to grant George’s request that the Braklaagte community should be recognised as a separate tribe, they did in fact function independently from the chief at Dinokana. When in 1926 they purchased the rest of Welverdiend, the headman of Braklaagte was given autonomy to facilitate the administration involved in the registration of the farm. To repay the debt incurred by the purchase of the farm a special rate of £2 per annum was later levied on each member of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa at Braklaagte.

In May 1929, at a tribal meeting in Zeerust, the chief, councillors and members of the tribe of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa resolved with a majority of votes to once again request the transfer of Braklaagte to the minister. A list of 255 names of male members of the tribe who had contributed to the purchase-price of Braklaagte, and of their descendants, was attached to the resolution. From the number of names on this list it is clear that the number of inhabitants of Braklaagte had increased considerably in the 21 years since the purchase of the farm in 1908. If each of the 255 men had on average three dependents, there were at that stage more than 1,000 people on Braklaagte and Welverdiend.

As a result of continued conflict between chief Abraham Moiloa of Dinokana and headman George Moiloa of Braklaagte the magistrate of Zeerust approached the Ministry of Native Affairs towards the end of 1933 and suggested that a headman should be elected by the inhabitants of Braklaagte. This headman should be appointed under the jurisdiction of the chief of Dinokana, with the qualification that the chief could not interfere in issues related to farmlands, dwelling-places, grazing rights and water. The headman would have the final say over these matters, with the right of appeal to the magistrate. Apparently the magistrate hoped that the democratic election of a headman would resolve the divisions in the ranks of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa.

On 23 February 1934 the election was held between two candidates, which were George Moiloa, the serving headman, and Johannes Moiloa, whose candidature was supported by chief Abraham Moiloa, his brother-in-law. George won the election by 134 votes to 116. Those who had voted for Johannes declared themselves willing to accept George’s appointment, provided that he fulfilled his responsibilities without usurping the powers of the chief again. George’s appointment as headman of Braklaagte, with civil and criminal jurisdiction, was approved by the Governor-General a full seven years later, in terms of the Native Administration Act (act no. 38 of 1927).

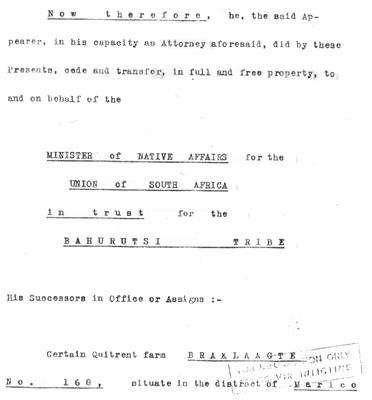

As far as the authorities were concerned the dispute among the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa had been settled with George’s election in 1934 and the transfer of the land could now proceed. The legal process for the transfer was set in motion and on 25 September 1935 the farm Braklaagte was transferred to the Minister of Native Affairs, who would hold it in trust for the particular section of the Bahurutshe tribe. The descendants of the members of the tribe who had contributed to the initial purchase-price of the farm would, in terms of the registered deed of transfer, have the only and exclusive right to the occupation and use of the land.

Figure 2.3: Extract from deed of transfer, 1935

It seemed as if this section of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa was now assured of their land, even though in terms of the discriminatory legislation of the Union of South Africa it could not remain their private property any longer.

Concluding remarks

The historical events narrated in this chapter can be linked to two of the central issues identified in the introduction as the focus of this book, that is, (1) the manipulation of ethnicity by the government to implement segregation and consolidate their control over black communities, and (2) the agency of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa at Braklaagte in maintaining as much independence as possible under a system of racial discrimination.

The way in which the South African government handled the internal strife between the two sections of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa at Dinokana and Braklaagte and the election of a new headman for Braklaagte sheds light on the manipulation of ethnicity and traditional leadership to support the implementation of segregationist policies. It demonstrated the other side of the coin of divide and rule strategies.

The fact that the government constantly refused to grant full autonomy to the people of Braklaagte as a separate tribe with their own chief, but at the same time granted jurisdiction over some domestic affairs to the headman at Braklaagte, was in line with the policies of the Department of Native Affairs. The Department did not wish to provide power bases for rural black communities outside the reserves. They regarded the chief at Dinokana as their agent who would ensure compliance of his subordinates with the implementation of government policies. The taxes imposed on the reserves made it virtually impossible for a chief to escape this role in the government system. The chief at Dinokana would be keen to maintain his jurisdiction over communities outside the reserve, such as the one at Braklaagte, because it enhanced his status among his own people and, if he performed his duties in a satisfactory way, would lead to a favourable assessment by the native commissioner. For the government it was all a matter of maintaining strict control over black communities, both inside and outside the reserves. The tension between Dinokana and Braklaagte could be, and was from time to time, utilised by the authorities to strengthen their control with regard to the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa.

The available sources do not indicate that the government unduly interfered with the election of a headman for Braklaagte in 1934. This was probably because there was no evidence in the possession of the local native commissioner that either of the candidates would resist compliance with government policies. Therefore the government probably had no special preference for either of the contenders.

The agency of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa at Braklaagte in working out their own destiny was clearly demonstrated by their purchase of the farm and the way in which they fought to retain their possession of the land. The initial purchase of Braklaagte was an act of defiance, not only against the segregationist policies of the Transvaal government and the capitalist-induced process of proletarianisation that threatened to force them into wage labour, but also, as a breakaway group, against being directly controlled by the ‘mother community’ at Dinokana. These people used the opportunity, created by a 1905 court ruling, to purchase their own land from a white farm owner, thus repossessing a small part of the former Bahurutshe heartland.

They had to actively fight the squatters laws and later also the 1913 Natives Land Act to hold on to the farm, even if it meant ceding their title to the Minister of Native Affairs. Despite the financial pressure on them created by the tax system they managed to slowly repay the mortgage. Ironically they managed to do this, at least in part, by selling the labour of the able-bodied men among them to the distant gold mines and regularly having a portion of their wages deducted by the local native commissioner. By the sweat of their brow they earned a right to the land.

—

Whose Land is it Anyway? (1908-1935) – Chapter 2 from: The Last Frontier War – Braklaagte and the Struggle for Land before during and after Apartheid – Kobus du Pisani.

Savusa Series co-published by:

Rozenberg Publishers – 2009 – ISBN 978 90 3610 090 8

Unisa Press – 2009 – ISBN 978 1 86888 562 6

The book tells the story of how a black community in rural South Africa, the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa, managed to hold on the farm which they purchased in 1908 and resist attempts by the successive white-controlled goverments to forcefully remove them from their land.

Braklaagte, the farm in the Northwestern corner of the country near the Botswana border, was in terms of the Land Act a “black spot” in “white” South Africa.

When the Apartheid regime failed to effect the forced removal of the community under resolute leadership of their traditional leader, John Lekoloane Sebogodi, they were first expropriated and later forcefully incorporated into the Bophuthatswana homeland. Thus losing their South African citizenship. The Braklaagte community lived through serious violence before being reincorporated into reunified South Africa in 1994.

The purpose of the book is not to tell the Braklaagte story for its own sake, but to interpret the narrative in the context of the discourses of South African historiography. This is achieved by focussing on three issues:

– The role of ethnicity and traditional leadership in Apartheid South Africa

– The relationship between insecurity of tenure and rural poverty

– The Braklaagte experience as proof of African agency in the face of oppression.

—

Kobus Du Pisani is Professor of History in the School of Social and Goverment Studies at the Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University. His research interests include Afrikaner masculinities, the environmental history of arid regions in South Africa, and cultural heritage management.