Introduction

Introduction

There is a considerable amount of material on FDI, the multinational enterprise (MNE) and the role of China in today’s globalised economy, and the literature considered in this chapter reflects the key issues under discussion. Initially, investment is defined and competing views on investment theory are considered, with the most suitable one for this study identified. Given the inter-twined linkage between FDI and multi-national enterprises (MNEs), the role of MNEs is explored, followed by an analysis of how FDI occurs at the level of the firm.

The limited literature on Irish outward FDI is also set out. Specifically, Barry et al’s model on Irish outward FDI is examined, so that the application of their hypothesis to the Chinese economy can be considered. This is followed by a consideration of the rise of FDI in China and the influence which China’s unique culture has on the FDI environment.

Investment Defined

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) offers a definition of foreign direct investment.

Direct investment is the category of international investment that reflects the objective of a resident entity in one economy obtaining a lasting interest in an enterprise resident in another economy. (The resident entity is the direct investor and the enterprise is the direct investment enterprise.) The lasting interest implies the existence of a long-term relationship between the direct investor and the enterprise and a significant degree of influence by the investor on the management of the enterprise. (IMF, 1993: 86)

The IMF goes on to define a direct investment enterprise ‘as an incorporated or unincorporated enterprise in which a direct investor, who is resident in another economy, owns 10% or more of the ordinary shares or voting power’. (IMF, 1993:86) This definition is aimed at providing a standard by which balance-of-payments data is compiled. However, it does not adequately address the issue of control.

The OECD (2006: 2) defines direct investment as a category of international investment made by a resident entity in one economy (direct investor) with the objective of establishing a lasting interest in an enterprise resident in an economy other than that of the investor (direct investment enterprise). ‘Lasting interest’ implies the existence of a long-term relationship between the direct investor and the enterprise and a significant degree of influence by the direct investor on the management of the direct investment enterprise.

Again, this definition is not precise enough for use in this research, as the issue of control is couched in terms of a ‘significant degree of influence’. Moosa (2002: 1) comes close to a workable definition when he defines FDI as ‘the process whereby residents of one country (the source country) acquire ownership of assets for the purpose of controlling the production, distribution and other activities of a firm in another country (the host country)’.

Lipsey (2001) contends that the United Nations System of National Accounts, which governs the compilation of national income data, appropriately addresses the concept of control. The UN System of National Accounts defines foreign controlled enterprises as subsidiaries of which more than 50% are owned by a foreign parent. (United Nations, 1993) This definition focuses on control and is the one which shall be used as our reference point. Investments below 50 per cent of a firm’s stock are either of a portfolio nature or offer the investor a minority shareholding. In seeking to explore potential Irish investment into China and gain a fuller appreciation of the complexities and challenges of FDI, the scope of this research includes only those firms which have a controlling interest. MNEs holding 50% of stock or less are, by their nature, restricted in the scope of their decision-making and influence. ‘The distinguishing feature of FDI, in comparison with other forms of international investment, is the element of control over management policy and decision’. (Moosa, 2002: 2)

For the purposes of this research, therefore, control is a central concept. The FDI relationship consists of a parent enterprise and a foreign affiliate which together form a multinational enterprise (MNE). Given the importance of MNEs and the central role which they play in FDI decisions, their role and structure is explored later in this chapter.

Having set out our working definition of FDI, it is important to distinguish between the two principal forms in which FDI takes place. Firstly firms can invest abroad to supply a market directly through a subsidiary, whereby production processes from the home economy are replicated in the host economy, and this is described as horizontal FDI. This form of FDI is often undertaken to exploit more fully certain monopolistic or oligopolistic advantages, such as patents or differentiated products. (Moosa, 2002) The second form, vertical FDI, is undertaken to locate low-cost locations for components of the production process, whereby certain elements are moved in their totality from the home to the host economy. Horizontal and vertical FDI should not be seen as competing theories. Rather, they seek to explain different rationale underlying

investment decisions.

All investments necessarily entail trade-offs and compromises. Horizontal FDI avoids trade costs but foregoes economies of scale, as production is diversified. Vertical FDI incurs the costs of splitting production over various geographic locations. ‘Theory suggests factors that are important in these tradeoffs; some of these factors are firm or industry specific (e.g. the importance of economies of scale), some are country characteristics (e.g. the market size or factory prices)’. (Navaretti and Venables, 2004: 127) It would appear that horizontal FDI is by far the major component of outward FDI. Moosa (2002) argues that horizontal FDI may be in the region of 70% of the total. Jim Markusen, one of the leading FDI scholars, states that horizontal exceeds vertical, but acknowledges the difficulty in quantifying this. Reliable data on the breakdown between horizontal and vertical FDI is difficult to obtain. While it can be assumed that horizontal FDI still dominates, the extent of such pre-eminence is unquantifiable.

Having defined FDI for the purposes of this research, it is appropriate to move to a consideration of the body of literature which exists on FDI theory. This literature provides an appropriate investment theory within which to locate our consideration of Barry et al’s model and the potential challenges and opportunities facing Irish investors into China.

Dunning’s Eclectic Paradigm Investment Theory

Our consideration of Irish outward FDI and its applicability to China should be considered within a framework of investment theory. While there is no universally accepted investment theory, this section will provide an analysis of the framework within which this research is considered.

Investment theories emerged in the post-war period, with the increasing importance of FDI and multinational enterprises (MNEs). Indeed, FDI theories have developed with MNEs at their core. Researchers sought to find theories to explain the actions of MNEs and the expansion of international production. The first such approach was Ohlin’s (1933) neo-classical theory, which focused on international trade theory and classic location theory. It was argued that international fund flows are caused by differences between resource endowments among competing countries. Therefore, investment should flow from capital-abundant countries to relatively capital-scarce countries, where higher marginal productivity can be achieved. Interest rate differential is seen as the variable which causes cross-border capital movements, which will cease when the marginal productivity of labour in competing countries is equalised. However, this approach has several defects. It fails to distinguish between direct and portfolio investments, so it does not address the issue of control. (Aliber’s (1970) capital-markets approach also fails to incorporate this distinction.) This theory assumes that production technologies are equally well-known in all trading countries and are characterised by constant returns to scale. Also, it is constructed on the premise of a perfect market, which assumes zero transaction costs. (Eckaus, 1987) These assumptions greatly weaken the theory. Perfect competition is a useful theory for economic analysis but rarely exists, if ever. For these reasons, this theory is of limited value in seeking to analyse FDI flows and the motivation of MNEs.

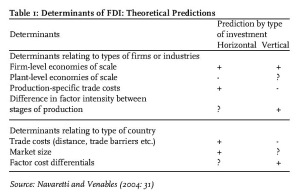

Vernon (1966) developed the product-cycle theory in order to explain the existence of international production as well as international trade. He argued that, as a product moves through its life-cycle, the characteristics of the product will move through three distinct stages, from a newly developed product to a mature product to a standardised product. Each stage has implications for production. In the development stage, production must be located close to markets. During the mature stage, a higher level of capital intensity is required. In the final stage, the standardisation of production means easier imitation and increased competition. Consequently, the firm has to search for low-cost labour in overseas production locations as a means of further reducing unit costs. Vernon’s theory was a response to the observation that US firms were among the first to develop new labour-saving techniques in response to the high cost of skilled labour and a large domestic market. (Du Pont, 2000) This theory proposes that the MNE needs to exploit its firm-specific advantages by moving from its home market to produce overseas in a low-cost location. Vernon made a significant contribution to the development of FDI theory, as he could explain most of the outward FDI from the USA in the 1960s. While this theory holds for some FDI, notably the movement of low-value manufacturing facilities from developed to developing economies, it does not provide an explanation for the flows of FDI between developed economies. Also, the focus on innovation makes it difficult to explain FDI in industries where innovation is not at its core.

Responding to the weaknesses in Ohlin’s (1933) neo-classical theory, Hymer (1960) developed the Industrial Organisation theory. Hymer argued that FDI is a result of market imperfections, which can be caused by either the market or government, particularly tariffs and trade barriers. (Mundell (1957) had earlier recognised that FDI develops when trade in goods is impeded.) Hymer went on to argue that companies operating in a foreign country face certain disadvantages in comparison with domestic companies, such as information costs, the business culture, and the political or economic operating environments. Domestic companies are likely to have lower operating costs. Therefore, in order for FDI to occur, foreign companies must have firm-specific advantages which allow them to compete with domestic firms. These advantages, which are of an intangible nature, include superior technology, brand names, financial strength, managerial or marketing skills. It has to be assumed that the firm’s intangible advantages are not available to local companies for some time after the foreign firm invests, otherwise the incentive to invest would be negated. Kindleberger (1969) developed this theory further when he argued that the comparative advantage has to be firm-specific, transferable to foreign subsidiaries, and large enough to overcome these disadvantages.

Hymer brought a new dimension to the consideration of FDI, which future researchers built on. Prior to his influential work, it was customary to treat equity investment on a par with capital flows, thereby failing to distinguish between equity and investment flows. (Du Pont, 2000) From a conceptual standpoint he introduced an analysis of the MNE as being central to our understanding of FDI. While Hymer’s theory introduces the notion of a spatial dimension it does not address the location advantages which certain economies possess or how the decision to invest is reached by the individual firm. One problem with this approach is that it fails to explain why the firm does not utilise its advantages by producing in the home economy and exporting abroad, which is an alternative to FDI. Even if one accepts the impetus to invest abroad because of lower input costs, Moosa (2002: 32) contends that this theory ‘does not explain why firms choose to invest in country A rather than country B’. Hymer’s theory does not provide a workable hypothesis for large MNEs which dominate international production. (Du Pont, 2000) Its only acknowledgement of location is that firms may invest in a third country in order to overcome tariffs, but the advantages which a particular location may or may not possess are not considered.

Buckley and Casson (1976) proposed an internalisation theory whose basic hypothesis is that multinational hierarchies represent an alternative mechanism for organising the firm across international boundaries. Firms are likely to engage in FDI whenever they perceive that the net benefits of ownership of foreign subsidiaries exceed those offered by international trading. (Du Pont, 2000) This theory moved away from explaining why an MNE invests abroad to the consideration of why MNEs decide to retain certain activities within the enterprise when undertaking FDI, rather than sub-contracting or licensing production. This approach centres on the logic that the market for intermediate products is difficult to manage and control, so manufacturing can be handled more efficiently within the firm. Therefore, an MNE is created when the firm decides to internalise such production across different markets. Internalisation theory negates the regulatory costs associated with operating in external markets i.e. tariffs can be avoided through local manufacturing. Thus, multinational companies prefer internalising production rather than exporting or licensing as a means of reducing transaction costs. (Williamson, 1985) However, Rugman (1980) argues that the hypothesis underlying this theory cannot be tested directly. Buckley and Casson (1989) acknowledge that statistical tests are bound to be based on simplifying assumptions and lead to the conclusion that the process of internalisation is concentrated where high incidences of R&D occur. While the internalisation theory contributes to the development of a theory of FDI and specifically that of the MNE, it fails to provide a comprehensive approach to the firm’s decision to invest abroad, specifically by lacking an analysis of the locational advantages and disadvantages which a particular country can offer. This theory is of use in analysing why MNEs decide to retain production within the firm rather than to sub-contract, and will be of benefit when considering the optimum means of protecting intellectual property rights when investing in China.

While the investment theories cited above make a contribution to our understanding of investment theory, they focus on partial elements of FDI. Dunning (1979a) built on earlier models of investment and set out a comprehensive explanation of FDI and the MNE. He combined the firm-specific ownership advantage which Hymer had identified with Buckley’s internalisation theory, and added a locational dimension. He built on Hymer’s hypothesis that for foreign firms to operate in a different environment requires the firm to have a firm-specific advantage which offsets potential disadvantages. Bringing together the strengths of earlier theories, Dunning (1977, 1979a and 1980) provides a conceptual framework in his eclectic paradigm model (also known as OLI Advantage).

Dunning sets out three basic advantages as preconditions for MNEs to successfully undertake FDI: Ownership-specific Advantage, Location-specific Advantage and Internalisation Advantage (OLI). Dunning argues that FDI occurs when these three conditions are met. Ownership-specific advantage is based on the concept that companies possess internal advantages which are specific to the firm and related to the accumulation of intangible assets, such as advanced technology, product differentiation, product innovation, financial strength, marketing expertise or managerial skills. These advantages come in the form of an asset which reduces the firm’s production costs and allow it to compete in foreign markets despite the increased costs associated with such a move. As economies have developed and globalisation has intensified, Dunning argues that there is a need for ‘firms to undertake FDI to protect, or augment, as well as to exploit, their existing O [ownership] specific advantages’.(Dunning, 2000a: 169) For FDI to occur, the ownership advantages have to be transferable to a foreign country and possible to use simultaneously in more than one location. Dunning’s ownership advantage is a restatement and expansion of Hymer’s industrial organisation theory. Where Dunning adds to Hymer’s theory is with the integration of location and internalisation advantages into one comprehensive model.

Dunning (1979a: 273) states that consideration of the questions associated with the choice of location was “not wholly satisfactory” as this issue has not been integrated with other theoretical approaches. Locational advantage refers to the institutional and productive factors available in a particular geographic area. ‘More often, they are related to market characteristics, trade barriers, cost conditions and the institutional and business environment’. (Van Den Bulcke et al, 2003: 13) Locational advantage determines whether or not a particular location is attractive to inward FDI, and a strong locational advantage will reduce the firm’s production costs. In the absence of locational advantage, the firm will produce in the home economy and export to the host economy.

Buckley (1989) contends that locational advantage enables MNEs to gain maximum advantage from differential prices of non-tradables in particular locations, particularly labour costs. These advantages are accentuated when they are combined with the inherent strengths of MNEs such as advanced technology, financial strength or marketing expertise. Dunning (2000a) points to the trend that many countries are endeavouring to provide the most appropriate economic and social infrastructure.

…a country or region’s comparative advantage, which has been traditionally based on its possession of a unique set of immobile natural resources and capabilities, is now more geared to its ability to offer a distinctive and non-imitable set of location bound created assets, including the presence of indigenous firms with which foreign MNEs might form alliances to complement their own core competencies.(Dunning, 2000a: 178)

Internalisation advantage determines how a firm uses its ownership advantage. In deciding to enter a third country it can decide either to license production to another firm or to establish a manufacturing facility itself. If the firm does not possess internalisation advantage, then it is more profitable for the firm to exploit its ownership advantage by licensing production to an external firm. Internalisation refers to the structure of the firm and its ability to meet the demands of interacting with the market place. Internalisation theory states that as long as the transaction and coordination costs of using external arm’s length markets in the exchange of intermediate products, information, technology, marketing techniques etc. exceed those incurred by internal hierarchies, then it will pay a firm to engage in FDI, rather than conclude a licensing or another market related agreement. (Dunning, 2000a: 179)

The reality is that foreign companies incur additional costs as compared with indigenous companies. These extra costs range from a culturally unfamiliar environment to legal and political uncertainties. Internalisation also avoids the difficulty of what Buckley (1987) terms ‘buyer uncertainty problem’. This can occur when a firm licences another enterprise to produce its goods. The licensee obtains a transfer of information. Once it has such information, there is a risk that the receiving firm no longer considers that it should continue to pay for it.

FDI occurs only when the firm possesses ownership and internalisation advantages and the host economy offers locational advantage. While possession of ownership advantage is required for a firm to operate in a foreign market, it is the existence of location and internalisation advantages which determines the manner in which the foreign market should be entered. Buckley and Casson (1998) found that all advantages are interconnected. They contend that within these three advantages ownership-specific advantage is the main determinant of why FDI is undertaken; location-specific advantage determines where to undertake FDI; and internalisation advantage determines how FDI should be undertaken. Ietto-Gillies (2005) contends that the strength of Dunning’s approach is the contemporaneous analysis of these three variable advantages.

Dunning’s contribution to FDI theory is that he provides a comprehensive framework for discussion of the motives underlying FDI. ‘The eclectic paradigm was developed by Dunning by integrating the industrial organisation hypothesis, the internalisation hypothesis and the location hypothesis’. (Moosa, 2002: 36) He also explains the choice of entry into foreign markets. The strength of Dunning’s model, as compared with earlier theories, is that it offers an inclusive and complete framework within which to analyse FDI and the role of the MNE.

This being said, Dunning has his critics. Ietto-Gillies (2005) argues that the original eclectic paradigm hypothesis is too wide to be useful in practice, with at least 20 possible ownership advantages, 11 internalisation advantages and 16 locational advantages to be considered. In later works Dunning acknowledges the difficulties which the number of variables can pose and uses terms such as ‘systemic framework’ or ‘paradigm’ rather than ‘theory’. ‘The eclectic paradigm is more to be regarded as a framework for analysing the determinants of international production than as a predictive theory of the multinational firm’. (Dunning, 2000b: 126) Dunning suggests that the key to operationalising his paradigm lies in contextualising the variables e.g. the contextualisation of the ownership advantage can be achieved by reference to the kind of multinational enterprise which is most appropriate to the activity, be it resource seeking, market seeking, efficiency seeking or asset seeking.

Dunning’s framework commands strong support within international business theorists. ‘Any conference on international business is likely to have a number of papers using Dunning’s framework. It has certainly been successful in introducing the taxonomy of OLI advantages’. (Ietto-Gillies, 2005: 117) ‘A striking feature of this [FDI] literature is its overwhelming reliance on the OLIparadigm framework’. (Du Pont, 2000: 21) Ietto-Giles accepts that the strongest point of Dunning’s approach is that he highlights how internationalisation and locational issues are interlinked. This means that issues specific to firms and their competitive advantages must be seen in conjunction with issues related to local conditions and to issues of markets and industrial organisation.

Given the diversity of opinion within academic writing, there is unlikely to be consensus on the most appropriate theory to explain FDI. ‘There is not one but a number of competing theories with varying degrees of power to explain FDI’. (Agarwal, 1980: 740) Most theories of FDI are under-determined and deal only partly with observed trends. (Du Pont, 2000) However, Dunning provides a framework within which to evaluate both the firm and the location chosen for FDI. Other theories consider these aspects in isolation. Du Pont (2000: 14), while a keen supporter of Hymer’s approach, acknowledges that:

Dunning offers a rich conceptual framework for explaining not only the level, form and growth of MNC activity, but also the way in which such activity is organised. Furthermore, the paradigm offers a robust tool for analysing the role of FDI as an engine of growth and development as well as for evaluating the extent to which the policies of source and host governments are likely both to affect and be affected by that activity.

In response to criticism that the eclectic paradigm is a static rather than dynamic analysis, Dunning developed the Investment Development Path (IDP) hypothesis:

The basic hypothesis of the IDP is that as a country develops, the configuration of the OLI advantages facing foreign-owned firms that might invest in that country, and that of its own firms that might invest overseas, undergoes change, and that it is possible to identify both the conditions making for the change and their effect on the trajectory of the country’s development. (Dunning, 2001: 180)

The IDP hypothesis ‘proposes that there is a U-shaped relationship between economic development and a country’s net outward investment position’. (Barry et al, 2003: 342) The IDP identifies five stages of development through which a country will pass. The first stage is one of pre-industrialisation, when a country has little or no inward or outward FDI because it does not possess sufficient locational advantages. As government policy develops or natural resources are exploited, the first wave of inward FDI will concentrate on the natural resource sectors, labour intensive industries, construction and possibly tourism. ‘Depending on the extent to which the country is able to create a satisfactory legal system, commercial infrastructure and business culture, and to provide the business sector with the transport and communication facilities and human resources they need; and depending on its government policy towards inward direct investment, its locational attractiveness will increase’. (Dunning, 2001: 181) This second stage sees the development of some location specific advantages which leads to inward FDI targeting the emerging domestic market in consumer goods and infrastructure.

The improvement in the locational advantage of a country may help indigenous firms to upgrade their own ownership advantage. As countries move along their development path, the OLI configuration facing outward and inward investors continues to change. Some foreign (and domestic) firms, which earlier found a country attractive to invest in because of its low labour costs or plentiful natural resources, no longer do so. In other cases its L [locational] advantages have become more attractive as an indigenous technological infrastructure and pool of skilled labour is built up. This, in turn, makes it possible for domestic firms to develop their own O [ownership] advantages and begin exporting capital. (Dunning, 2001: 181)

Stage three witnesses a modest rate of growth in inward FDI, which is eventually overtaken by outward FDI. The fourth stage sees the country become a net outward investor with location advantage based on created assets and indigenous firms’ ownership advantage. Dunning contends that whether this happens or not depends on the strategy of individual firms and the policies of national governments to generate the competitive advantage of domestic firms and by making the location attractive to both domestic and foreign investors.

The final stage sees the net FDI flow position approaching zero with permanently high stocks of both inward and outward FDI. The net FDI flow position will be determined by short-term trends related to exchange rates and economic cycles. Dunning and Narula (1996) argue that this stage of development has been reached by the more advanced industrialised economies, whose wealth creation and productivity growth are increasingly based on the ability to utilise intellectual capital. It is possible to identify the Irish investment experience in several of the stages identified by Dunning. We shall return to this below when we consider the composition of Irish outward FDI.

Dunning sets out a theory which is broadly accepted internationally, and which provides a strong analytical framework in which to locate this research. No other theory offers such a holistic and dynamic approach or can so adequately encompass the characteristics of the firm and the specific attributes of the location chosen for inward FDI. For this reason, it is chosen as the framework for the analysis in which the nature and scope of Irish outward FDI into China is explored.

The Role of the Multinational Enterprise in FDI

It was the attempt to explain the actions of MNEs and the expansion of international production which led to the development of FDI theory. Indeed, FDI and MNEs are so intertwined that the motivation for FDI may be used to distinguish between MNEs and other firms. (Moosa, 2002) An understanding of why investment by a foreign firm differs from that made by a domestic firm assists in our appreciating the dynamics which underlie FDI. As FDI entails higher costs for the investing firm, MNEs must possess an advantage over local firms sufficient to offset the costs of international coordination, or the locational benefits will be captured instead by indigenous firms. (Froot, 1993) FDI has been described as the highest commitment a firm can make in international business as it involves not only the infusion of capital but also the transfer of personnel and technology. (Daniels and Radebaugh, 1995) Research in the areas of MNEs and FDI provides a theoretical underpinning which suggests that the MNEs’ ability to organise their unique, firm-specific assets and resources over many countries and exploit the advantages of operating in these countries fundamentally alters their approach to business, the nature of their assets and resources, and accordingly the impact they have on host countries. (Scott-kennel, 2004)

In seeking to understand the role of MNEs, Hymer ‘is regarded as a seminal figure in the establishment of the theory of the multinational enterprise’.[i] (Buckley, 2006: 140) Hymer clearly distinguished between portfolio and direct investment, with the latter offering managerial control.

Hymer focused on the specific advantages which the firm possesses, which enable it to engage in outward FDI. Hymer borrowed D.H. Robertson’s description of MNEs as ‘islands of conscious power in an ocean of unconscious co-operation’. (Hymer, 1970: 441) He forecast that increasing specialisation by MNEs would force the global economy to become spatially specialised with a hierarchy of specialised locations emerging. However, Graham (2006) points to Hymer’s lack of success in arriving at a dynamic model of the MNE. Buckley and Casson (1998) argue that there is a need for a new agenda in models of the MNE based on dynamic analysis and a move away from Hymer’s static analysis. Such a new agenda ‘highlights the uncertainty that is generated by volatility in the international business environment. To cope with flexibility, corporate strategies have to be flexible’. (Buckley and Casson, 1998: 22)

Navaretti and Venables (2004) see such a dynamic existing in Dunning’s eclectic paradigm. In analysing Dunning’s work they outline three defining questions underlying a firm’s decision to internationalise – what are the costs and benefits to the firm of splitting production; whether the firm’s foreign activities should be internal to the firm or outsourced to independent operators; and what are the effects of multinational activity on the home and host countries. These three issues are now examined in turn.

The decision on whether to concentrate production in a single country or disperse it across several countries has associated costs and benefits. The cost of splitting off production to a third country also entails costs in terms of the efficient use of factors of production. Multinationality is most likely to occur when there are high firm-scale economies, combined with relatively low plantscale economies. Navaretti and Venables (2004) argue that the gain in market power will be even greater if the investment takes the form of a merger or acquisition, which directly eliminates a potential rival. ‘Market power considerations are a major motivation behind both domestic and international M&A activity’. (Navaretti and Venables, 2004: 28) But this form of market entry poses particular challenges in China, a matter we shall return to later.

A perceived benefit of investing abroad is the incentive to reduce production costs.

MNEs will gain from moving unskilled labour-intensive activities to countries where unskilled wages are low, R&D-intensive activities to places where scientists are relatively cheap and so on. The expansion of EU investments in Central and Eastern Europe countries, US investments in Mexico, and the investments in software companies in Bangalore are all driven by the aim of reducing costs of production.(Navaretti and Venables, 2004: 29)

They qualify this statement by pointing out that factor prices have to be adjusted for the quality of the factor input. ‘The evidence suggests that FDI rarely goes to the lowest-wage economies, going in preference to countries that have abundant labour with basic education… Firms look at the cost of labour, not its abundance’. (Navaretti and Venables, 2004: 29)

From an organisational perspective, FDI is a choice to retain functions internally within the firm rather than relying on other actors in the market. There is also the option of licensing the franchising. There are costs and benefits associated with retaining the function internally or relying on market transactions. ‘Internalising may bring a direct cost penalty, but avoids problems of contractual incompleteness in dealing with outside agents’. (Navaretti and Venables, 2004: 25) Internalising production also has the advantage of better protecting one’s intellectual property. The protection of intellectual property is an on-going challenge in the Chinese economy, an issue which will be considered in chapter four.

The decision to internationalise one’s production has an effect on both the host and the home economies. Navaretti and Venables (2004) identify three channels through which the effects on host (receiving) and home (sending) countries are transmitted: product market effects, factor market effects and ‘spillover effects’. In the case of product market effects, the firm undertaking FDI will change the quantity of goods it buys and sells in the host and home country when it undertakes FDI. In the case of substitute products in the host economy, local firms may be unable to sell as much produce as heretofore and crowding-out can occur. Consequently, consumers may not be any better off and local firms may be forced to sell less or perhaps leave the market. Alternatively, the MNE may increase competition in the marketplace and perhaps also increase quality or variety, which will subsequently raise consumer welfare. If the MNE has higher productivity than local enterprises, then consumers may see a price reduction.

Factor market effects can occur in both labour and capital markets. In general, when a MNE sets up in a host country, there is an inflow of funds. It is not normal practice to raise the funds on the local market (this is a pertinent issue in the construction sector in China, an issue that we will return to, given the strength of this sector in traditional Irish outward FDI). In the case of the labour market, a range of situations may occur. The demand for different categories of labour will increase in the host economy and may fall in the home economy, depending on the type of investment undertaken. The establishment of an MNE may also have an impact on skilled labour in both economies. If the jobs being established in the host economy require a certain degree of skill and such skill is in short supply, then wage levels will increase as employees move between companies. This phenomenon is currently evident among English-speaking educated Chinese executives, for whom there is an ever-increasing demand, particularly in areas such as Shanghai and Guandong. As stated above, this issue features in our research.

It is argued that the most important benefits to accrue from FDI are a variety of ‘spillovers’, which may be technological or pecuniary externalities. The former arise when FDI imposes costs or benefits that are not directly transmitted through markets. The latter arise when effects transmitted through markets are not fully paid for, so parties to the transaction may receive economic surplus. (Navaretti and Venables, 2004: 41) Technological externalities include technology transfer and the acquisition of labour skills. ‘It [FDI] can bring not only capital but also new technologies and skills that might not otherwise be obtainable’. (Eckaus, 1987: 127) Technological changes have not simply altered the ways in which firms conduct their overseas business activities, but they have made possible the creation of a new infrastructure for carrying out diverse operations within a unified structure. (Du Pont, 2000) The insistence of the Chinese authorities on obtaining a transfer of technology through FDI will be considered during our research. Also considered will be the potential impact which this has for firms seeking to protect intellectual property rights.

… the overwhelming evidence for MNEs both operating abroad (foreign subsidiaries) and at home (headquarters and home plants) is that they perform better than fully national firms… The analysis of firm-level data for the UK, the US, Italy and various other developed and developing countries reports that average labour productivity in foreign subsidiaries of MNEs is between 30% and 70% higher than in national firms and for the home activities of MNEs it is approximately 30% higher’. (Navaretti and Venables, 2004: 42)

MNEs do not perform better simply because they are multinational players. They are larger in scale, engage in R&D, use more capital and generally employ more skilled labour. Vaupel (1971) compared US MNEs as with domestic US firms. He found that MNEs incurred higher R&D expenditure, had higher net profits, had higher average sales, paid higher wages in the US, and had a higher export/sales ratio. Using an econometric model, Grubaugh (1987) obtained results supporting the importance of R&D, product diversity and size as characteristics of MNEs. The emphasis on R&D confirms the link with Dunning’s ownership advantage. By pursuing R&D, the firm increases its internal advantage and affords itself higher levels of technology than its rivals.

Policy makers should be reassured by the evidence that when a national firm transfers part of its production to cheap-labour countries or is bought out by foreign investors, its performance is generally better than if the firm had not invested abroad or had stayed national. Moreover, MNEs often have features (size, R&D, investments, brands etc.) that national firms do not have and which in themselves are important, as they enrich the domestic production structure and they improve its average performance. (Navaretti and Venables, 2004: 43)

This is an important consideration and one which we shall return to in chapter five, during our discussion of public policy on outward FDI.

Why FDI Occurs?

Dunning offers a theoretical framework within which investment occurs and which will guide the consideration of our hypothesis. However, it is also important to explore the specific motivation which leads to the individual firm’s investing in a third country.

Hewko (2002) argues that if a country offers significant business opportunities and does not present any formal barriers to investment it will attract foreign investment. As the market size grows to a critical value, FDI will start to increase with further expansion. Navaretti and Venables (2004: 141) contend that ‘the larger the host market the greater the likelihood that MNEs will be able to recoup the fixed cost of their foreign plants’. Secondly, a stable political and social environment is conducive to the attraction of FDI. Conversely, large and unexpected modifications of legal and fiscal frameworks may drastically change the economic outcome of a given investment.

Studies indicate that the effect of labour cost on FDI is controversial. Goldberg (1972), Saunders (1983), Schneider and Frey (1985), Culem (1988) and Moore (1993) found that a rise in the host country’s wage rate would discourage FDI. On the other hand, Nankani (1979), Kravis and Lipsey (1988) and Wheeler and Mody (1990) found the opposite. A possible explanation for these conflicting results is offered by Lucas (1993), who shows that a rise in the wage rate of the host country means an increase in the costs of production, which should discourage production and consequently inward FDI. However, the increase in wage levels may cause a movement to more capital-intensive means of production, which may result in higher inward FDI. It is fair to assume that in the case of low-skill, high-volume manufacturing, labour costs are an important determining factor. However, as companies increase the value of their output, skill levels increase and the manufacturing process becomes more complex. Quality skilled labour is then likely to assume a higher degree of importance, with less emphasis on labour costs. Navaretti and Venables (2004: 140) contend that the reason for the mixed results is because of the need to differentiate between horizontal and vertical FDI. ‘[W]e expect VFDI to increase with differences in factor endowments and factor costs, as this is precisely what investors are looking for’. Reuber et al (1973) assert that low labour costs in developing countries provide the basis for high rates of return on export-oriented products. This assertion will be examined later in the case of China, specifically in the case of Irish FDI into China.

A country’s degree of openness to international trade should have a direct relationship to the level of FDI. Kravis and Lipsey (1988) report a strong positive effect of openness on FDI. Wheeler & Mody (1992) observed strong evidence in the manufacturing sector, but a weak negative link in the electronics sector. This points to the lack of homogeneity in FDI. There are various submarkets for FDI depending on the level of skill, value of output etc. This issue will be revisited when determining which sectors of the Irish economy hold the most potential in terms of inward FDI into China. Allied to this is the question of tariffs.

Studies find that tariff jumping is an important motive for investments in the US and EU. For example, Barrell and Pain (1999b) examine the determinants of aggregate flows of Japanese FDI into both the European Union and US in the 1980s. They find that Japanese FDI into a particular country is strongly influenced by the extent of that country’s trade protection measures and, in particular, by its extent of antidumping activities.’ (Navaretti and Venables, 2004: 137) Countries that are more open to trade tend to provide and receive higher levels of FDI. (Lipsey, 2000) Bajo-Rubio and Sosvilla-Rivero (1994) found a significant effect of the tariff rate on FDI. Indeed, Blonigen and Feenstra (1996) suggest that FDI may be induced by the threat to introduce protectionist measures. A further consideration is the relative strength or weakness of the host economy’s currency. The weaker the currency of a country, the less likely are foreign firms to invest in that location. This is because an income stream from a country with a weak currency is associated with exchange rate risk, and an income stream is therefore capitalised at a higher rate by the market when it is owned by a weak currency firm. Chakrabarti (2003) states that a strong currency is often interpreted as an indication of the greater competitiveness of the host country.

Intercultural transaction costs are inevitable when cultures meet. They are produced by mistrust, miscommunication, language difficulties, clashing values, conflicting senses of propriety etc. Prejudice or ignorance may distort the investor’s perception of the foreign market. The host-country consumer may have a disdain for goods made by a particular country. Cultural compatibility can enhance a destination for foreign investors, but cultural estrangement can nullify the attractiveness. The importance of Chinese culture will be considered further in this chapter, given its strong influence in Chinese society.

Another consideration is the efficiency and transparency of the legal system. A transparent legal system reduces transaction costs for economic actors and is of considerable benefit in attracting FDI. Needless to say, an arbitrary legal system will be relatively uninviting for investors. In the latter case, there may be some investors who are willing to invest on the basis of very high potential returns, but generally investors require legal certainty.

Finally, most governments adopt policies aimed at encouraging inward FDI by offering incentives. Moosa (2002) identifies the incentives which governments offer as tax reductions, exemption from customs duties, accelerated depreciation, grants, loan guarantees, market preference (including monopoly rights) and low cost infrastructure. The effect of incentives in successfully attracting FDI is far from clear. It is arguable that incentives benefit a firm which would have made the investment in any event. The results of Agarwal’s (1980) empirical studies show that incentives have a limited effect on the level of FDI, as investors base their decision on risk and return considerations. Reuber at al (1973) found that incentives can play a role in encouraging small firms with limited experience, but their overall impact is small.

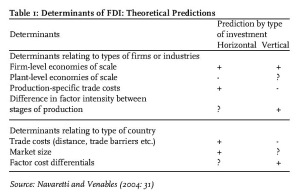

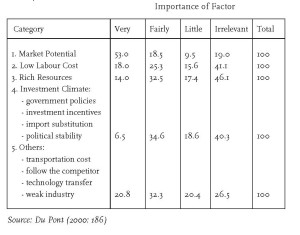

Views diverge on the effect of taxation on FDI. ‘Hines (1999), in his survey of empirical studies, concludes that “the econometric work of the last 15 years provides ample evidence on the sensitivity of the level and location of FDI to tax treatments”.… There is also evidence that responsiveness to tax has increased in recent years, as might be expected if VFDI, which is not tied to serving a particular market, has increased in importance’. (Navaretti and Venables, 2004: 139) Buckley (1987) argues that the urge to avail oneself of transfer price manipulations may induce a bias towards low tax countries. Devereux and Griffith (1998) contend that differences in taxation policies have an impact once the decision to invest overseas has already been made, but not in the making of the decision itself. Newman and Sullivan (1988) conclude that the modelling and estimation limitations of existing studies make it difficult to reject the hypothesis that taxes influence business location, but the results are not clear. The views of commentators on the effect of taxation are mixed. Taxation is part of a package of measures which investors find attractive. It is the overall environment of a particular country, as constituted by its political, social and economic conditions, which attracts FDI. (Moosa, 2002) Common determinants of FDI emerge from the above literature: market size, labour costs, trade barriers, the growth rate, openness, the exchange rate, political certainty, culture shock, the legal system and business opportunities. Theoretically, the size of the host market, low labour costs, fiscal incentives, a favourable business climate, and trade openness should have positive impacts on FDI, while high transportation costs, bureaucratic red tape, and political instability should act as disincentives. Table 1 gives some useful pointers in determining the likelihood of whether a firm will invest in a particular country or not.

Table 1: Determinants of FDI: Theoretical Predictions

Source: Navaretti and Venables (2004: 31)

These factors should be borne in mind when considering the determinants relating to which sectors of the Irish economy should focus their attention on China. Vertical FDI is likely to occur when factor cost savings are large relative to the costs of fragmenting activities in two or more locations. The table shows a clear prediction in the case of horizontal FDI and market potential. This will emerge as one of the key rationale for Irish firms investing in China.

Having set out the theoretical framework within which this research will be conducted and the role of MNEs in today’s globalised economy, the literature on Irish outward FDI is now considered.

Irish Outward FDI

By way of introduction, it is important to point out that there is a limited amount of literature on Irish outward FDI. While Forfás, the Irish Government’s national policy and advisory board for enterprise, trade, science and technology, has conducted one study on Irish outward FDI, the key published work in mainstream academic journals is Barry et al (2003). Both Barry et al’s and Forfás’ analyses have focussed on the US and UK as a destination for outward FDI. The findings of a survey undertaken by the Irish Business and Employers Federation (IBEC, 2006) on trade and investment with Asia will also be considered. While most of the data refers to trade, some interesting observations are made on investing in China. In addition, the perceptions of firms on trade issues may be of benefit in corroborating the findings of this research e.g. in the domain of intellectual property rights.

Forfás (2001) refers to Ireland’s successful track record in attracting inward FDI. It also acknowledges the growing trend of outward FDI by Irish multinationals but points to the absence of analysis of this issue. It points out that traditionally the bulk of Irish FDI outflows came from a relatively small number of Irish firms. ‘While these “old economy” firms still dominate the stock of Irish-owned direct investment assets overseas, a small number of “new economy” high-technology firms have recently started to make significant overseas investments’ (Forfás, 2001: 4).

Forfás (2001) alludes to the lack of statistical data on Irish outward FDI. There are three reference sources, the Central Statistics Office (CSO), Eurostat and the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). However, both UNCTAD and Eurostat source their data from the CSO. The information available is limited and does not provide a comprehensive time-series on Irish outward direct investment flows and stocks by sector of origin or country of destination. Accepting this caveat, an analysis of the data for recent years points to an interesting change in patterns in Irish investment.

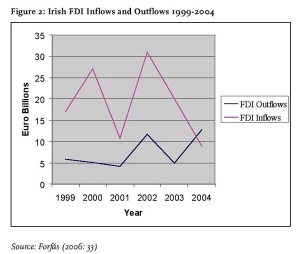

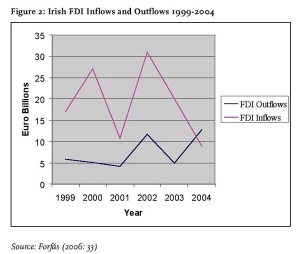

Figure 2: Irish FDI Inflows and Outflows 1999-2004

Source: Forfás (2006: 33)

The most interesting data available is the significant change in FDI flows since 2001. FDI outflows have increased significantly since 2001, and in 2004 were the largest ever recorded at € 12.7 billion. (Forfás, 2006) Figure 2 gives a representation of the changing trends in Irish FDI.

This graph identifies a sharp decline in inward FDI and a gradual increase in outflows.

Ireland was previously characterised by exceptionally high inflows and average outflows for a developed country. The trends of 2004 may signal a departure from this trend. Inflows of € 9.1 billion in 2004 represented a sharp decline from the peak of € 31.2 billion achieved in 2002, even though inflows still remain high relative to other similar countries. Much of this decline was due to particularly large repatriation of profits by multinationals in 2004. This trend is likely to continue in 2005 and 2006, as changes to US tax law subject earnings by US companies based in Ireland to considerably lower tax rates. (Forfás, 2006: 39)

We can say that an important milestone was reached in 2004 when outflows exceeded inflows for the first time by € 3.6 billion. (CSO, 2006) Barry et al (2003) have examined this trend and argue that it provides evidence of Ireland’s conforming to Dunning’s IDP hypothesis.

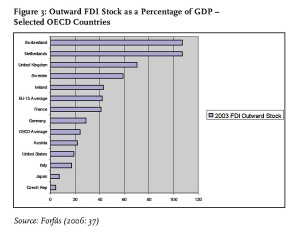

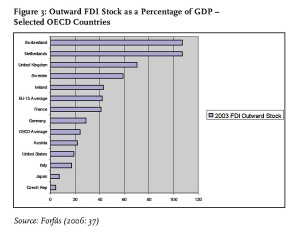

The cumulative Irish stock of FDI invested abroad is estimated to be € 61 billion in 2004. This is equal to 41% of GDP, which is similar to the ratio for the EU-15 as a whole. (Forfás, 2006) However, three years earlier Forfás (2001) pointed out that the ratio of stock of outward FDI to the stock of inward FDI was lower in Ireland than in any other advanced economy and was significantly lower than in most other small EU countries. ‘Ireland’s rather unique direct investment relationship with the rest of the world reflects not only the high levels of inward investment into Ireland compared with other advanced countries, but also very low levels of outward investment flows from Ireland’. (Forfás, 2001: 8)

The low levels of outward FDI reflect a number of historical factors. With the exception of financial services, Ireland has few large indigenous firms in the industries that generally generate the bulk of global FDI flows, such as oil, cars, telecommunications, electronics and pharmaceuticals. ‘Other factors included Ireland’s relatively recent industrialisation, the historically heavy focus of development policy on inward investment, and the more active promotion and facilitation of outward investment by other EU governments’. (Forfás, 2001: 10)

Figure 3: Outward FDI Stock as a Percentage of GDP – Selected OECD Countries

Source: Forfás (2006: 37)

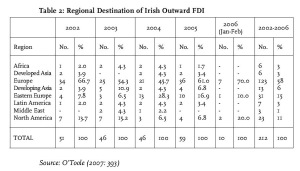

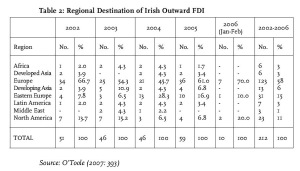

Detailed official statistics are not available on the destination of Irish outward FDI. The most informative information available is provided by LOCOmonitor (2006), a global database that tracks greenfield projects internationally and identifies 212 instances of Irish outward FDI in the period 2002 to 2006 (two months only). Table 2 sets out the regional destination of Irish outward FDI.

This data should be treated with caution as it relates to Greenfield investments only and does not include mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Accepting this caveat, this data shows that the most important destinations for Irish outward FDI are Western and Eastern Europe and North America. ‘Within Western Europe, FDI to the United Kingdom is by far the most important destination, accounting for two-thirds of Irish FDI to Europe… It is also notable that Asia, including developed countries such as Japan and developing countries like China, attracted less than 10% of Irish FDI projects in the period 2002-2006’. (O’Toole, 2007:392) A detailed breakdown by country is not available, but the provision of such information in future years would add greatly to our ability to analyse outward FDI flows.

Barry’s model on Irish outward FDI

As set out above, the Investment Development Path (IDP) hypothesis proposes that the changing pattern in FDI flows is systematically related to a country’s level of economic development. With increasing economic prosperity, a country evolves from being a net recipient of investment to being a net outward investor.

Barry et al (2003) contend that Ireland is an interesting IDP test case because of its rapid economic development and the heavy reliance of Ireland on inward FDI as compared with other EU countries. They examine if, given the magnitude of inward FDI, the pattern predicted by the IDP concept is realised. Pointing to the unavailability of time-series data over a considerable period on outward FDI flows, they show that Ireland in the late 1990s had the third largest stock of inward FDI in the EU, after Belgium/Luxembourg and the Netherlands[ii]. On the other hand, Ireland’s stock of outward investment was the third lowest. ‘This suggests that until recently outward FDI flows from Ireland were not very large, as the IDP concept would suggest’. (Barry et al, 2003: 342)

While acknowledging the lack of consistent time-series data on outflows from Ireland, Barry et al (2003) argue that there is evidence of increasing outflows, which is consistent with the Investment Development Path hypothesis. Using CSO data and material from the US Department of Commerce (the only source of a comprehensive time-series on both FDI inflows and outflows by nationality), Barry et al (2003) point out that Irish FDI into the US grew more rapidly than US FDI into Ireland in the 1980s and 1990s, to such a degree that they were broadly similar by the end of the 1990s. Their analysis of US data ‘provide[s] evidence of a U-shaped relationship between Irish GDP and the country’s net outward FDI position with the US, a pattern consistent with the IDP concept’. (Barry et al, 2003: 345)

Table 2: Regional Destination of Irish Outward FDI

Source: O’Toole (2007: 393)

While the IDP concept is silent on the distinction between vertical and horizontal FDI, Barry et al (2003) predict that as production costs rise there is an incentive for domestic firms to engage in vertical FDI, moving labour-intensive components to countries with a locational advantage in low-cost labour.

Later in the process, firms are able to compete in overseas markets and so engage in horizontal FDI. The incentive for horizontal outward FDI may develop as the economy becomes wealthier and domestic firms seek to maintain their competitiveness. (Barry et al, 2003) Also, economic development results in rising labour costs in the home economy, leading to a reduction in inward investment flows, and creates an incentive to engage in vertical FDI.

Turning to the composition of Irish outward FDI, Barry et al (2003: 345) analyse the available global data on the sectoral destination of Irish acquisitions overseas and identify that “the bulk of Irish outward FDI is of the horizontal type.” They also point out that outward FDI is predominately in non-traded sectors. Their work is a valuable and important contribution to our understanding of Irish outward FDI as it identifies the nature and composition of Irish FDI in the case of the largest markets in which Irish investment is made, i.e. the UK and US. This research, which focuses exclusively on China, adds further to our knowledge as it is examines Irish outward FDI to a developing economy.

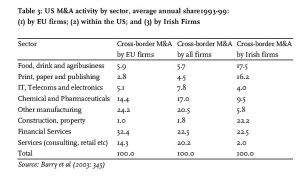

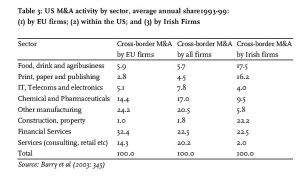

Table 3 sets out the sectoral distribution of overseas acquisitions in the US by EU firms, by all countries and by Irish firms. [iii]

The second column shows the sectoral composition of acquisitions by all overseas firms in the US. Data for this group is broadly similar to that for acquisitions by EU firms, with the exception of the financial services sector, which has a greater dominance among EU acquisitions. What is striking is the divergence of Irish acquisitions from these two groups. The most important sectors for Irish acquisitions are financial services;

Table 3: US M&A activity by sector, average annual share1993-99: (1) by EU firms; (2) within the US; and (3) by Irish Firms

Source: Barry et al (2003: 345)

construction; food, drink and agribusiness; and print, paper and publishing. The result for the financial service sector is broadly in line with the data for all investment in the US, approximately ten per cent below the EU data. Barry et al (2003) point out that as the food, drink and agribusiness sector accounts for 27% of Irish manufacturing employment compared to 12% within the EU15, the result for this sector is not greatly surprising. However, the figure for the construction sector is notable and reflects the traditional strength of this sector in the Irish economy with outward FDI having a historical basis. ‘Expansion abroad in such largely nontradable sectors entails horizontal rather than vertical FDI. If companies in these sectors expand abroad they do so for market-access reasons i.e. in order to penetrate and grow in new markets’. (Barry et al, 2003: 345)

Barry et al (2003) point to a large increase in 2000 by Irish firms in hi-tech sectors such as information technology and the pharmaceutical industry. The IDP concept would indicate that this development is a consequence of economic convergence. This points to a new generation of Irish MNEs investing abroad and supports the trend identified by Forfás (2001).

Barry et al (2003) question why there is so little outward Irish vertical FDI to lower-cost production locations. Recalling that firms invest abroad because they possess firm-specific assets (ownership and internalisation advantages), it is suggested that ‘R&D and superior product differentiation through advertising are generally found to be the most important firm-specific assets associated with multinationality’. (Caves, 1996; Markusen, 1995)… ‘Irish multinational companies do not appear therefore to follow the standard pattern associated with multinationality’. (Barry et al, 2003: 346) They propose that the predominant proprietary assets which Irish firms possess are in the fields of management and expertise, mainly in non-traded sectors.

Barry et al suggest that proprietary assets other than R&D and advertising appear to be associated with the horizontal multinationalisation of Irish firms. ‘The fact that the proprietary assets of Irish MNEs do not lie in these areas serves as an illustration of the difficulties facing firms in late-developing regions in surmounting the entry barriers that characterise more conventionally multinational sectors’. (Barry et al, 2003: 346)

Ireland’s development along the Investment Development Path and the nature of its outward FDI has implications for Irish investment in China. This research analyses the relevance of Barry’s model that Irish outward FDI flows are disproportionately horizontal and oriented towards non-internationally traded sectors, for Irish FDI into China by undertaking research among all Irish companies (employing ten or more staff) which have invested in China. This permits an analysis of whether or not such FDI is disproportionately horizontal.

Furthermore, the composition of Irish FDI in China to date is examined to analyse whether it is to be found in the internationally-traded or non-traded sectors.

China and Inward FDI

Wei and Liu (2001) identify China’s decision in 1979 to accept FDI as being the result of a fundamental shift in political leadership and economic policy. The new Chinese leadership recognised that attracting FDI was important for several reasons. It would introduce foreign capital without increasing China’s external debt. It would introduce advanced technology, equipment and managerial expertise. It would help improve technology levels in existing industry and introduce export-oriented practices. It would increase China’s social capital through training and skill transfer. Finally, it would create additional jobs, probably at higher wage levels.

There have been four distinct phases of development of FDI in China since 1979: the experimental period (1979-83); the gradual development period (1984-91); the peak period (1992-98); and the adjustment period (1998-present). In the experimental period (1979-1983) a limited amount of FDI was introduced into four special economic zones (SEZs) – Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou and Xiamen. Foreign investors had no experience of investing in China since 1949 and were likely to be reluctant. However, these regions enjoyed strong links with Hong Kong and Taiwan. Accordingly, investors from Hong Kong and Taiwan were more likely to avail themselves of the opportunity to invest.

Over the past twenty-five years Chinese GDP and per capita GDP have grown at an annual rate of 9% and 8% respectively. In the last few years economies such as China and India have become the most favoured destinations for FDI as investor confidence in these countries has soared. According to the FDI Confidence Index (A. T. Kearney, 2005), China and India hold the first and second position respectively, whereas the United States has slipped to third position.

Until recently the dominant source of inward FDI in China has been Hong Kong, followed by Japan, the United States and Taiwan. Approximately 59% of FDI has gone to the manufacturing sector, much of which is in labour-intensive industries such as textiles and mechanical and electronic products. (Wei and Liu, 2001) With structural changes in the Chinese economy the composition of inward FDI has also altered. In 1989, 83.3% of FDI was in manufacturing sectors. By 1993 this figure had dropped to 45.9%, while the share of real estate and utilities had risen from 9.4% to 39.3% in the same period. (Du Pont, 2000) This sharp increase in real estate and utilities is of interest to commentators on Irish outward FDI given the level of outward Irish FDI in the construction sector. The movement away from manufacturing in favour of the service sector should be of benefit to Irish investors given the predominately non-traded nature of Irish outward FDI, as identified by Barry et al. This issue will be re-examined following the elucidation of the results of our research.

Li and Li (1999) explore the reasons why MNEs invest in China. They identify two categories of investors in China. Firstly investors from developed economies, such as EU countries, USA and Japan, who tend to invest in the larger cities such as Shanghai, Guangzhou, Tianjing, Dalian and Beijing. They tend to introduce new technology, new management styles, the scale of investment tends to be larger and the focus is on exploiting market opportunity.

The second category comprises mainly Asian investors (excluding Japan), such as Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore and South Korea. Investments from this category are mostly in labour-intensive industries with production geared towards exporting. The size of the investment tends to be smaller and few investments bring new technology to China. Li and Li (1999) argue that while cheap labour is an important determinant for MNEs in this category, companies in the first category are likely to be attracted by the large and growing consumer market and the significant potential for future development. This phenomenon will be explored in our research to examine whether or not Irish MNEs conform to this categorisation.

While FDI is still concentrated in the coastal region, the Chinese Government currently has a policy of ‘opening up the west’. This will see a strong push to open up central and western regions of the country with associated government incentives, and can be expected to be a dominant theme in the next phase of China’s FDI history. This policy has a bearing on inward investment decisions and will be explored later within the context of our consideration of the regional dimension of FDI in China.

While Chinese society has undergone profound changes in the past twentyfive years and has made unprecedented gains in economic growth, traditional values still exert a strong influence. The investment challenges which China holds will be explored fully in chapter three, but two areas, relationships and contract law, are of particular importance to the conduct of business in China. Accordingly, they will be considered at this stage in order to provide a foundation for our later discussion.

Relationships and Contract Law

At the inter-cultural level, networking can bridge the gap between business people of different nations and cultures, hence stimulating trade and investment (Luo, 1998). Networking at both a personal and corporate level in China has its roots in Chinese culture and Confucianism. A particular form of networking has developed over the centuries and is referred to as Guanxi. This refers to the concept of drawing on connections so as to secure favours within a structure of personal relations. It is an intricate and pervasive relational network which Chinese cultivate energetically, with a history of more than 2,000 years. (Luo, 1998) The difference between guanxi and western business networking is that the former also includes social as well as commercial contact. Chinese businesspeople believe that one should develop a relationship and, if this is successful, business will follow. In contrast, western business people believe that a relationship may develop following the conclusion of successful business transactions. (Ambler and Styles, 2000; Tsang, 1998) Both guanxi and western networking emphasise that relationships are not discrete events in time, but are of a continuing nature. A notable difference is that guanxi leads to a strengthening of social relations, which may or may not be called upon in the future.

Guanxi also exists at an organisational level. Inter-organisational guanxi (guanxi hu) builds upon personal relations. Commentators such as Xin and Pearce (1996) argue that, since the cradle-to-grave provision of social services by one’s employer (referred to as the ‘iron rice bowl’) was broken in the early 1980s with the advent of foreign companies, the application of guanxi at the organisational level has become more pervasive and intensive. Any firm in Chinese society, be it local or foreign, inevitably faces guanxi dynamics. (Luo, 1998) Guanxi requires business people to develop relations not only with suppliers and customers, but also with key government officials. ‘Such personal connections are imperative to managers in China given the absence of the stable legal and regulatory environment that would facilitate impersonal business activities. Institutional uncertainty during economic transformation has been quite high’. (Luo, 1998: 172)

Jones (1994) argues that business practice in China relies on guanxi rather than on law and legal institutions as the basis of security of expectations. She states that guanxi provides a crucial role in business activities, being the basis for trust. It is therefore a source of stability, certainty, predictability and risk-reduction. Guanxi can serve as a substitute for legal enforcement and fills the void left by the absence of a developed legal system. (Jones, 1994) Guanxi provides a ‘substitute form of trust that can improve the profitability of investment and reduce the risk of arbitrary bureaucratic interference that is not in the interests of investors’. (Smart, 1993: 398)

Jones (1994) contends that a distinctive form of capitalism has developed in China and she asks how one can explain the success of an economy dominated by the ‘rule of relationships’ rather than the ‘rule of law’, as predicted by Weber’s hypothesis.

According to Weber, the operation of market capitalism depends on the existence of incentive to engage in economic activities, and the security of expectation of economic benefit flowing from such activities is an essential element of such incentive. Such security can only be provided by the predictable application of state coercion through logically formal and rational law… [This] type of legal system constitutes a favourable, and almost essential, condition for market capitalism. (Chen, 1999: 99)

Jones states that, when the spectacular success of Hong Kong is repeated in Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea and now China (which she labels the ‘fifth tiger’), the possible common denominator is their shared cultural emphasis on familial and business networks as opposed to legal institutions. (Chen, 1999) These are ‘the very things Weber regarded as barriers to capitalism’. (Jones, 1994: 197) Weberians tend to distinguish between the universalistic West and the particularistic East, depicting the Western model as being favourable to capitalism and the particularistic East as inimical to it. Jones (1994) argues that in China particularism is in the ascendant (in the form of guanxi and familism), defying theories that associate Western universalistic values with the growth of capitalism. ‘[D]espite its lack of formal legal rationality, mainland China also seems able to provide sufficient predictability, calculability and stability for capitalism to thrive. It can be argued that guanxi facilitates rather than hinders this process’. (Jones, 1994: 200)

Jones (1994) suggests that the rule of law is relatively absent from China and that guanxi is frequently preferred. She draws on Unger’s differentiated notion of law to identify the legal and quasi-legal forms found in modern China, which may be either interactional, bureaucratic/regulatory or full legal order[iv].

The final category is what one normally associates with the Western concept of the Rule of Law. Jones (1994: 204) argues that ‘while law in China is primarily of the second sort (that is regulatory/bureaucratic), China is a legally pluralistic society in which guanxi plays a central role but “full legal order” is absent’.

Guanxi therefore enables business to be done with strangers in a context of mutual trust and certainty; those who break this trust show ‘bad faith’ and stand to lose an important form of social capital, that is their reputation or ‘face’. In a society which places great importance on ‘face’ and trust, breaking faith may mean expulsion from guanxi-networks and exclusion from future business deals. (Jones, 1994: 205)

Contemporary China suggests that the existence of a rational legal system, in the Weberian sense, may not be a necessary or highly relevant condition for the development of a market economy. (Chen, 1999) Indeed, the Chinese authorities have stated clearly that, while the Western model of economic development was adopted, it was never intended to adopt the Western notion of the Rule of Law. (Deng Xiaoping speaking in 1988) The notion of the separation of powers was anathema to Deng Xiaoping, the architect of the opening-up policy – once a decision has been taken it could be implemented without ‘one branch of government holding up another’. (Xiaoping, 1988, cited in Jones, 1994) ‘Chinese law is an instrument of politics to be interpreted not by an autonomous judiciary but by the National People’s Congress’. (Jones, 1994: 208)

This leads one to ask if normal business can be conducted where a pervasive network of relationships exists. In particular, do western investors face challenges given the lack of the legal certainty which they would be accustomed to in areas such as contract law? But is contract law an absolute reference point in the conduct of commercial activity in Western society? In his seminal study on non-contractual relations in business, Macauley (1963) sets out a view of contract law[v] in the West which is open to interpretation, contestation and modification. His study outlines a scenario where relationships are central to business transactions, with little recourse to legal sanctions. ‘Business exchanges in nonspeculative areas are usually adjusted without dispute’. (Macauley, 1963: 60)

Business people try to solve conflicts themselves and in so doing they do not refer to the content of the contract. (Roxenhall and Ghauri, 2004) Indeed ‘law suits for breach of contract appear to be rare’. (Macauley, 1963: 60)

Macauley (1963) asks why contracts and legal sanctions appear relatively unimportant in the business world. He identifies the understanding of an agreement by both sides as ensuring that the nature and quality of a seller’s performance is understood. This understanding is facilitated by experienced professionals who are familiar with industry specifications and standards. In addition, there are alternatives to legal sanctions associated with the firm’s standing in the industry, such as the honouring of one’s commitments and the perception that the quality of one’s product is to be trusted. ‘At all levels of the two business units, personal relationships across the boundaries of the two organisations exert pressures for conformity to expectations’. (Macauley, 1963: 63) The ultimate non-legal sanction is the desire to maintain a successful business relationship.

Businesspeople often prefer to rely on informal agreements, such as a handshake, rather than to agree to a formal contract. Roxenahall and Ghauri (2004) argue that this occurs because parties want to continue to do business with each other in future. Macauley (1963: 64) contends that ‘not only are contract and contract law not needed in many situations, their use may have, or may be thought to have, undesirable consequences. Detailed negotiated contracts can get in the way of creating good exchange relationships between business units’. Pointing to the negative dimensions of contracts, he argues that the existence of a contract may result in performance being satisfied only to the letter of the contract. Businesspeople at times want a degree of vagueness so that they can react to changed circumstances. In addition, resorting to litigation will inevitably mean an end to the business relationship. Nevertheless, Macauley (1963) envisages situations where the threat of legal sanctions will have more advantages than disadvantages. These include the internal needs of an organisation, where pressure is required on departments within the firm to ensure that standards are achieved, where complex performances are agreed over a long time period, and where default is thought to have potentially serious repercussions.

Overall, Macauley (1963) identifies a reluctance among businesspeople to engage in negotiating contracts. Even when they do and one party defaults, there is a marked reluctance to pursue legal avenues. This is because businesspeople see a relationship as more important than one particular transaction. Given the importance of establishing a strong network of relationships in China (guanxi) and the relative lack of importance of detailed contracts in the conduct of business among western business people, one would assume that investors in China should not be particularly interested in concluding formal and detailed contracts with Chinese partners. This issue will be explored in our research with the executives of firms which have invested in China, to discover if, given the strength of guanxi in China, trust and credibility play a more salient role than legal contracts. (Tsang, 1998)

Conclusion

This chapter provides an overview of the most pertinent literature on key issues which will guide our future discussion. The definition of investment which has been adopted centres on management control and this will inform the selection of firms for inclusion in our research. While there are several theories on investment, it is argued that Dunning’s eclectic paradigm provides a comprehensive and dynamic approach. It builds on the work of earlier theorists such as Hymer. It sets out three preconditions which must exist for FDI to be successful – ownership-specific advantage; location-specific advantage; and internalisation advantage. FDI theories such as Dunning’s have developed with the role of MNEs as central to our understanding of foreign direct investment.

As the largest recipient of inward FDI, China exerts a key influence in international economic decisions. FDI in China has made remarkable strides since the ‘opening up’ policy was introduced in 1979. In the space of one generation it has become a magnet for FDI. That said, the business environment holds challenges, particularly in the deep culture of relationships and the underdeveloped nature of the legal system.