ISSA Proceedings 2006 – Revolutionary Rhetoric – Georg Büchner’s “Der Hessische Landbote“ (1834). A Case Study

1. Georg Büchner’s Political Pamphlet “Der Hessische Landbote” (1834): Historical Background and Persuasive Effect

1. Georg Büchner’s Political Pamphlet “Der Hessische Landbote” (1834): Historical Background and Persuasive Effect

If we want to understand and interpret Büchner’s revolutionary rhetoric in his pamphlet “Der Hessische Landbote”, we have to take into account the political and social context, that is, the historical situation of the duchy Hessen-Darmstadt in the 30’s of the 19th century. In this context, several political reforms initiated by Duke Ludewig I. (1753-1830) have to be mentioned positively, namely, the abolishment of peonage, the declaration of a constitution and the introduction of elective franchise; moreover, the Duke’s theatre and library were opened for the general public. However, these reforms at the beginning of the 19th century remained half-hearted. For example, even after the abolishment of peonage, certain feudal tax privileges remained. In this way, many farmers had to suffer an intolerable double burden of the traditional taxes paid to the nobility and the newly introduced taxes paid to the central authorities of Hessen (cf. Franz 1987, p. 38). The right to be elected remained restricted to the wealthy citizens. Finally, the laws abolishing the traditional guild system and introducing free trade caused the bankruptcy of craftsmen through the newly created competition of cheap factory products from foreign countries.

Furthermore, from 1830 onwards, Duke Ludewig II. (1777-1848) returned to a conservative policy, with much less social ambitions than his father Ludewig I. Consequently, Ludewig II. let his prime minister Carl W. H. du Bos du Thil (1777-1859) use authoritarian methods, for example, the brutal knock down of social riots in the northern parts of Hessen.

In 1834, the year of the publication of “Der Hessische Landbote”, the duchy Hessen-Darmstadt had about 720.000 inhabitants, whose majority, especially in rural areas, suffered from extreme poverty. Almost 50% of the population lived just at or below the level of subsistence, 40-45% of the working population (including children over the age of 12 and elderly people) had to work 12-18 hours a day (cf. Schaub 1976, p. 99; Hauschild 2000, p. 19 and p. 43).

In this dramatic situation, Georg Büchner (1813-1827), who is well-known as a brilliant German writer, radical political thinker and distinguished scientist in the fields of medicine and biology, decided to contribute to a revolutionary change of the intolerable social situation via political propaganda. Büchner was born in Goddelau and grew up in the capital of the duchy, Darmstadt. He was the son of the successful physician Dr. Ernst Karl Büchner and his wife Caroline. Among his numerous siblings, Wilhelm Büchner (1816-1892) stands out as the inventor of artificial ultramarine, Luise Büchner (1821-1877) became a distinguished writer and feminist and Ludwig Büchner (1824-1899) was a well-known materialist philosopher.

After finishing grammar school in Darmstadt, Georg Büchner studied medicine in Straßburg, the centre of German political emigration, where he probably established contacts with revolutionary circles in the years 1831-1833. Büchner continued his studies in Gießen 1833-1834, and founded a section of the “Society of Human Rights”, first in Gießen, later in Darmstadt. In this society, pre-communistic theories were discussed. Büchner developed an increasingly critical view of the political reality within the duchy and the other countries of the political confederation “Deutscher Bund” bordering on Hessen-Darmstadt. Through his friend August Becker, Büchner got to know the Protestant pastor Friedrich Ludwig Weidig (1791-1837), the leading head of the liberal-democratic opposition in northern Hessen.

In the beginning of the year 1834, Büchner wrote his pamphlet “Der Hessische Landbote” (“The Hessian Courier”) as a call for a general revolution. To mobilize the masses, he mainly criticized their enormous tax burden: About 700.000 citizens had to pay more than 6 millions “guilders” (“Gulden”) and were thus exploited by a minority of about 10.000 privileged people. However, Büchner did not have any illusions about causing a revolution of the masses solely by means of publishing this pamphlet. He mainly intended to inform the population drastically about its desperate political situation and to test if he could arouse general indignation, which in the long run could lead to an uprising of the masses (cf. Schaub 1976, p. 142; Hauschild 2000, p. 54; cf. also Glebke 1995, pp. 62f., who assumes that Büchner believed in the possibility of initiating a revolution, in spite of his deterministic view of human history).

It is quite clear that Büchner was more radical than the liberal-democratic opposition of his time. He had the intention to abolish the enormous gap between the rich and the poor and to overthrow the political system which made it possible. His brother Ludwig wrote the following about the political point of view of Georg Büchner: “Was seinen politischen Charakter anlangt, so war Büchner noch mehr Sozialist, als Republikaner” (“As to his political character, Büchner was more of a socialist than a republican”; cf. Hauschild 2000, p. 51). And what is more, Georg Büchner was a socialist in the sense of a radical egalitarian, who went as far as the abolishment of private property, as his friend August Becker remarked (cf. Hauschild 2000, p. 51). Therefore, Büchner’s pamphlet differs from earlier revolutionary texts in the German speaking area through its systematic criticism and it is a forerunner of anarchist and Marxist political programs (cf., however, Glebke, 1995, pp. 97f., who sees Büchner as a representative of a liberal-democratic point of view).

To soften the radical design of Büchner’s “Landbote”, Weidig revised the original text because he was afraid to offend the liberal opposition, which he wanted to win over as an ally. He composed an introduction, which advised the audience to take precautions when reading and keeping the text, and wrote a conclusion which he formulated as a prayer. Furthermore, he inserted many quotations from the Bible (but cf. Schaub 1976, pp. 49ff., who doubts that Weidig indeed introduced all or most of the Bible quotations). He also probably deleted passages especially criticizing the liberal bourgeoisie and added passages with a strongly idealized view of the former German emperorship (abolished in the year 1806). Weidig did all that without informing Büchner, who was very upset about Weidig’s modifications. Büchner remained loyal, however, and helped with the preparations of the print. The “Landsbote” appeared in July, 1834, the first edition comprising 1000 copies.

Already in August, 1834, Carl Minnigerode, a member of the Gießen section of the “Society of Human Rights”, was arrested while trying to distribute copies of the “Landbote”. Büchner succeeded in avoiding arrest by cold-bloodedly making up alibis. In September, 1834 he went to Darmstadt and tried to reorganize the local section of the “Society of Human Rights”, to free Minnigerode and other arrested members and to organize the print of further editions of the “Landbote”. In October, 1834, the situation became ever more threatening for Büchner because the police continued receiving detailed information about the revolutionary circles from police spies.

In March, 1835, Büchner fled to Straßburg. Gustav Clemm, a member of the Gießen section gave away the names of the conspirators, which led to numerous arrests. Among the arrested were Weidig, who was brutally tortured during his detention and committed suicide in 1837, and Becker, who remained in detention for four years, and emigrated to Switzerland and the USA after his release.

As far as the persuasive success of the “Landbote” is concerned, there are contradictory claims. At his interrogation, August Becker declared that most of the farmers brought their copies of the pamphlet to the police (cf. Schaub 1976, p. 143). However, in his book “Die Volksphilosophie unserer Tage” (“The philosophy of the people in our times”, 1843), which he wrote when he was free again, Becker stressed the fact that the “Landsbote” successfully aroused the emotions of the people (cf. Schaub 1976, p. 53) and that Weidig met farmers who were extraordinarily impressed by the pamphlet (cf. Schaub 1976, p. 143). What is more, if the first edition had not had a recognizable impact,Weidig would not have published the second edition of the “Landbote” in November, 1834. The lecturer at the University of Marburg, Eichelberg, planned to write a second issue of the “Landbote”, which also makes it more plausible that it was efficient in persuading the population. Last not least, the assessment of the “Landbote” by representatives of the authorities of Hessen (e.g. Konrad Georgi, Martin Schäffer), who considered it to be most dangerous, revolutionary and populist, suggests that it was adequate for its intended purpose (cf. Schaub 1976: p. 144).

2. Argumentative Structure of “Der Hessische Landbote”

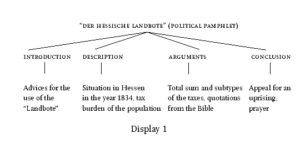

Der “Hessische Landbote” belongs to the genre of the political pamphlet, that is, a subtype of argumentative discourse. This is reflected in its argumentative super-structure (cf. van Dijk 1980), which can be divided into four main sections:

1. The “Landbote” begins with an introduction, which is set off from the main text by formal means such as a headline (Vorbericht), a typographically deviating smaller font size, a black line, but also as far as content is concerned. The introduction contains only measures of precaution concerning the reading, storing and further distribution of the “Landbote”.

2. The title of the main part Friede den Hütten! Krieg den Palästen! (“Peace to the huts, war to the palaces”) is a free translation of the slogan of the French writer and revolutionary Nicolas de Chamfort (1741-1794), who allegedly suggested this slogan for the soldiers of the French revolutionary armies: “Guerre aux chateaux! Paix aux chaumières!” (literally: “War to the castles! Peace to the thatched cottages!”; cf. Schaub 1976, 75). The title is followed by a detailed description of the deplorable social situation in Hessen-Darmstadt. This descriptive part contains several argumentative passages, but the first four paragraphs remain mainly descriptive. Within these paragraphs, the extreme discrepancy between the situation of the rich and the poor in the duchy in the year 1834 is vividly described. After that, the total sum of the taxes and the subtypes of taxes are enumerated and the concept of “state” is defined (Der Staat also sind alle = “The state are all (citizens)”). Finally, the disproportion between the masses of exploited citizens (about 700.000) and the small ruling elite and the oppressive bureaucracy is severely criticized.

3. In the following argumentative part of the “Landbote” Büchner follows two main strategies. On the one hand, he quotes the sums of the respective subtypes of taxes according to the contemporary statistical survey by G.W.J. Wagner (1831; cf. Franz 1987, West 1987, Mayer 1987) and thus argues, using empirical and inductive arguments, for the justification of the revolution (cf. the paragraphs 5-15 of the “Landbote”). On the other hand, Büchner and Weidig appeal to the authority of the Bible, quoting about 80 passages of the Old and New Testament in order to legitimize the revolution (cf. the paragraphs 16-21 of the “Landbote”). It remains a controversial question whether these quotations were written solely by Weidig, which is is the mainstream opinion in the research on Büchner, or whether Büchner used the Bible passages already in the original version of the text (cf. Schaub 1976, p. 50).

4. The conclusion (paragraphs 22-25) contains Büchner’s thesis that a revolution is unavoidable and is characterized by the increasing use of imperatives (cf. § 22, at the beginning: Hebt die Augen auf (“Look and see!”), at the end: erhebet euch (“stand up!”); § 25 wühlt, stürzt, wachet, rüstet, betet, lehrt (“dig!”, “overthrow!”, “wake up!”, “prepare!”, “pray!”, “teach!”). The very end is a prayer with the concluding formula Amen (“Amen”). This structure is summarized within Display 1:

Büchner’s argumentative strategies will be illustrated in the first sentences of the fifth paragraph of the argumentative part of the “Landbote”. These sentences are reproduced according to the original orthography, which is sometimes mistaken (cf. the printing error “Innrrn” instead of “Innern”). In this passage, Büchner severely criticizes the tax burden for the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Justice, because the taxes in this institutional area are spent for obscure, inefficient laws, which are to the disadvantage of the people. Therefore, so-called “justice” is only a means to stabilize the power of the ruling elite and the exploitation of the masses (cf.. Büchner 1834, p. 3):

(1) Für das Ministerium des Innrrn und der Gerechtigkeitspflege werden bezahlt 1,110,607 Gulden. Dafür habt ihr einen Wust von Gesetzen, zusammengehäuft aus willkührlichen Verordnungen aller Jahrhunderte, meist geschrieben in einer fremden Sprache. Der Unsinn aller vorigen Geschlechter hat sich darin auf euch vererbt, der Druck, unter dem sie erlagen, sich auf euch fortgewälzt. Das Gesetz ist das Eigenthum einer unbedeutenden Klasse von Vornehmen und Gelehrten, die sich durch ihr eignes Machwerk die Herrschaft zuspricht. Diese Gerechtigkeit ist nur ein Mittel, euch in Ordnung zu halten, damit man euch bequemer schinde.

(For the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Justice, 1.110.607 Guilders are paid. For this, you get a tangle of laws, compiled from arbitrary decrees of all centuries, most of the time written in a strange language. The nonsense of all preceding generations has been left to you there, the pressure they succumbed to has rolled over onto you. The law is the property of an insignificant class of aristocrats and scholars, who assign themselves control through their own broth. This justice is only a means to keep you down in order to torment you more conveniently)

The arguments appearing in this passage can be subsumed under wide spread types or schemes of everyday argumentation (cf. Kienpointner 1992, pp. 250ff.). The prevailing types are causal schemes (e.g. means-end arguments or pragmatic arguments, which highlight the positive or negative effects of certain acts).

Empirical indicators for the plausibility of these susumptions are lexical and syntactic means of expression such as Dafür (“For this”; Dafür habt ihr einen Wust…) in the first sentence, which indicates that unsufficient means have been used in order to achieve a certain end (cf. the negative connotations of Wust von Gesetzen “a tangle of laws” and in einer fremden Sprache “in a strange language”, that is, a language difficult to understand for ordinary people). The second argument is a pragmatic argument (cf. Perelman/Olbrechts-Tyteca 1983, p. 358). It presupposes that the laws in Hessen are the negative effects of a lack of critical attention of former generations (cf. Der Unsinn aller vorigen Geschlechter hat sich … vererbt; …hat … sich … fortgewälzt “The nonsense of all preceding generations has been left; …has rolled over onto you”).

The third argument has the form of a (persuasively formulated) definition (cf. Walton 2005) according to the classical pattern “X is Y (genus proximum), and Y is characterized by the property Z (differentia specifica): Das Gesetz ist das Eigentum einer unbedeutenden Klasse von Vornehmen…., die sich … die Herrschaft zuspricht (“The law (= X) is the property of an insignificant class of aristocrats and scholars (= Y), who […](= Z)”). The fourth argument criticizes that the taxes for the administration of justice are only a means for a bad end (… nur ein Mittel … damit man euch bequemer schinde “…only a means … in order to torment you more conveniently”).

The radical style of these arguments could be judged as being exaggerated and overly hostile. In spite of the highly polemical formulations and the pungency of Büchner’s criticism, however, the misery of the masses in Hessen in the year 1834 justifies an overall evaluation of these causal arguments as basically plausible. Taken together with the following arguments in paragraph 5, they sufficiently support Büchner’s claim that the taxes for the administration of internal affairs and justice are abused to maintain an unjust and inefficient system. The first four arguments of paragraph 5 can be summarized as follows (cf. display 2):

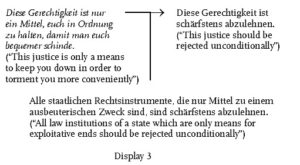

For the explicit reconstruction of the microstructure of the fourth particular argument of this passage, which based on the means-end relation (Diese Gerechtigkeit ist nur ein Mittel, euch in Ordnung zu halten, damit man euch bequemer schinde “This justice is only a means to keep you down in order to torment you more conveniently”), I am going to use a tripartite model of argumentation. It contains the three basic elements of the well-known Toulmin model (cf. Toulmin 1958, Toulmin et al. 1984, Kopperschmidt 1980, pp. 91ff.; Kienpointner 1992, pp. 24ff.; Van Eemeren/Grootendorst/Snoeck Henkemans 1996, pp. 129ff.; Freeman 2005). This tripartite model contains only those elements of the Toulmin model which are indispensable for any simple, single argumentation, namely, the thesis (= the controversial claim, the point of view), the argument (here understood in the narrow sense, that is, the grounds supporting or attacking the thesis) and the warrant (the semantic relations granting the relevance of the arguments for the thesis).

There is no algorithm or mechanical procedure for the explicit reconstruction of the schemes underlying argumentative passages. But there are a few rules of thumb for the reconstruction of implicit elements:

1. Most of the time, in everyday argumentation only the arguments (in the narrow sense mentioned above, that is, the grounds supporting/attacking a thesis) are formulated explicitly.

2. The default explicitation should aim for a logically valid reconstruction, unless there is strong evidence for assuming an invalid underlying scheme. In many cases, the Modus ponens (“If p, then q; p; therefore, q”), the Modus tollens (“If p, then q; not q; therefore, not p”) or the Disjunctive Syllogism (“Either p or q; not p; therefore, q”) are such valid schemes as to serve as the underlying formal structures.

3. The implicit elements should be supplemented on the basis of those elements which are explicitly mentioned. This means that the reconstruction should be as close as possible to the explicitly mentioned elements of the schemes and add only as many implicit elements as seem to be necessary.

4. Reconstructing the warrant, we have to choose between a logical minimum, which can be, for example, the conditional premise of the Modus ponens (“If p, then q”) and the pragmatic maximum, that is, more general reconstructions, for example, “All X are Y” or “Mosts X are Y”. A decision in this respect has to be taken on the basis of the verbal and situational context and the reconstruction of the intentions of the speaker/writer. In addition to the explicitly formulated means-ends argument Diese Gerechtigkeit ist nur ein Mittel, euch in Ordnung zu halten, damit man euch bequemer schinde (“This justice is only a means to keep you down in order to torment you more conveniently”), and on the basis of our knowledge about the radical political point of view of Büchner, we can reconstruct a radical thesis and a highly general and far-reaching warrant (cf. display 3; the explicit elements in Büchner’s text are in italics):

Critical questions for evaluating means-ends arguments can be given as follows: Are the means sufficient to achieve the end? Are there better means to achieve the end? Can the means be justified by the end? Are the means (only) used to achieve a bad end? (etc.). The last one of these critical questions could be asked to test Büchner’s means-ends argumentation. It can be doubted whether the administration of justice in Hessen in the year 1834 was really only a means (cf. […] nur ein Mittel […]) for maintaining the rule of the elite and to stabilize the system of exploitation. There could also have been elements of justice which transcended the class system. However, taking into account the miserable situation of the poor and their double tax burden, we could evaluate the harsh criticism formulated by Büchner in this argument as well as in other means-end arguments at least as not being totally exaggerated.

3. Stilistic Presentation of the Argumentation in “Der Hessische Landbote”

The aggressiveness of Büchner’s argumentation in “Der Hessische Landbote” is increased by a series of brilliantly used stylistic techniques such as parallel clause structure, anaphors, rhetorical questions, metaphors and metonymies. Especially the metaphors and metonymies are used for making the mechanisms of complex power and domination structures vivid and understandable also for the masses, with the help of personifications (metaphors) and spatio-temporal contiguity (metonymies).

In the passage from §5 analysed above, these techniques can be illustrated, for example, by the frequent use of parallel constructions at the level of the phrase and the clause structure. In the following example, the parallel structures are visualized by labelled bracketing (PART = participle, PP = prepositional phrase; SUBJ = subject, ATTR = attribute, PRED = predicate)(cf. Büchner 1834, 3):

(2) Dafür habt ihr einen Wust von Gesetzen,

[PART zusammengehäuft [PP aus willkührlichen Verordnungen …]],

[PART meist geschrieben [PP in einer fremden Sprache]].

[SUBJ Der Unsinn [ATTR aller vorigen Geschlechter]] [PRÄD hat sich darin [PP auf euch] vererbt],

[SUBJ der Druck, [ATTR unter dem sie erlagen]], [PRÄD [hat] sich [PP auf euch] fortgewälzt].

As the cognitive theory of metaphor has amply shown, metaphors are not only esthetic devices for the embellishment of texts, but rather important ingredients of our thought, which they shape considerably (cf. Lakoff/Johnson, Lakoff 1987). This has an important impact on the political discourse of all involved parties (cf. Lakoff 2005). Büchner used metaphorical characterizations in order to make abstract entities such as laws accessible: They are portrayed as concrete objects, which are inherited and which move, and justice is personified as a tyrant, who torments the people.

In the other paragraphs of the “Landbote”, too, metaphorical images are used to visualize the system of exploitation and to portray the ruling elite and the bureaucracy as vampires, dangerous beasts and criminals. In this way, Büchner’s attacks and criticisms are much more understandable and persuasive than a purely abstract analysis could have been. In the whole text, I count about 40 persuasive metaphors which serve this function, supplemented by six explicit similes.

Here are a few examples: Justice is the whore (Hure) of the dukes, (Büchner 1834, p. 3). Revenue officers are merciful to the same degree as someone who spares cattle which he does not want to decimate too much (wie man ein Vieh schont, das man nicht so sehr angreifen will (Büchner 1834, p. 4). The soldiers are legal murderers (Mörder), who protect legal robbers (Räuber) (Büchner 1834, p. 4). A sincere minister would only be a string puppet (eine Drahtpuppe), being pulled by the duke, who himself is only a puppet (Puppe) pulled by influential persons at his court (Büchner 1834, p. 4). The Hessian people behaves like the pagans, who worship the crocodile (das Krokodill), which rips them to pieces (Büchner 1834, p. 2; actually, this page 2 = 5; a printing error). The duke has his foot on the neck of the people (seinen Fuß auf einem Nacken; Büchner 1834, 2 = 5). The duke, his ministers and officials are the head, the teeth and the tail of a leech creeping over the people (Der Fürst ist der Kopf des Blutigels, der über euch hinkriecht, die Minister sind seine Zähne und die Beamten sein Schwanz; cf. Büchner 1834, p. 2 = 5). The ‘noble’ exploitators are only strong because they suck the blood of the people away (das Blut, das sie euch aussaugen; Büchner 1834, p. 8).

Metonymies are often employed to suggest that taxes are wasted for paying the highly expensive furniture and luxurious wardrobe of people serving for the authorities, such as policemen or officials. This is achieved by using the principle of spatial contiguity and part-whole relationships for a vivid description of the system of taxes, privileges and exploitation. The resting chairs of the officials stand on a huge heap of Guilders, the tail coats of the policemen are embroidered with silver taken from the taxes of the people (Ihre Ruhestühle stehen auf einem Geldhaufen von 461,373 Gulden (so viel betragen die Ausgaben für die Gerichtshöfe und die Kriminalkosten). Die Fräcke, Stöcke und Säbel ihrer unverletzlichen Diener sind mit dem Silber von 197,502 Gulden beschlagen (so viel kostet die Polizei überhaupt, die Gensdarmerie u.s.w.; cf. Büchner 1834, p. 3).

4. Critical Evaluation of the Revolutionary Rhetoric in Büchners “Landbote”

As for the explicitation of implicit elements of an argumentation scheme (cf. above, section 2), there are no algorithms or mechanical procedures for the evaluation of argumentative texts. Especially a critical analysis of political discourse should not forget an important insight of Mannheim (1929, p. 32), namely, that the thought of all social groups and in all historical periods is bound to a certain ideology (“das menschliche Denken [ist] bei allen Parteien und in sämtlichen Epochen ideologisch”). So-called ‘objective’ descriptions and evaluations of political argumentation often run into the danger of reifying and immunizing the own ideological position. Therefore, it is better to make one’s own standpoint explicit – in my case, a leftist standpoint – and to try to judge the strength and weaknesses of political discourse as impartially as possible (cf. Kienpointner 2005).

In line with these preliminary remarks, I am going to discuss a few argumentative strengths and weaknesses of Büchner’s “Der Hessische Landbote”. More particularly, I would like to provide some tentative answers to the question whether Büchner’s revolutionary rhetoric can be judged to be an instance of legitimate “strategic maneuvering” or as a “derailment of strategic maneuvering”, that is, as (wholly or partially) fallacious. I understand “strategic maneuvering” in the sense of van Eemeren/Houtlosser (2002a, p. 16):

[…] strategic maneuvering can take place in making an expedient selection from the options constituting the topical potential associated with a particular discussion stage, selecting a responsive adaption to audience demand, and exploiting the appropriate presentational devices. Given a certain difference of opinion, speakers or writers will choose the material they can most appropriately deal with, make the moves that most acceptable to the audience, and employ the most effective presentational means.

I would like to start with some critical remarks. At the level of the presentational devices, it can be criticized that the metaphorical characterizations of Büchner’s political enemies are formulated in such an aggressive way that their negative evaluation as instances of abusive ad hominem arguments can hardly be avoided. As far as the level of adaption to audience demand is concerned, they strongly appeal to emotions like hatred and envy of the masses and can, therefore, be plausibly criticized as instances of ad populum arguments, that is, as populist appeals. Indeed, many of these attacks are insults rather than rationally justifiable arguments and therefore, can be classified as emotional fallacies (on criticizing these and other types of emotional fallacies cf. van Eemeren/Grootendorst 1992, Walton 1992, 1998, 1999; Doury 2004).

At the level of the topical potential, Büchner’s (or Weidig’s) strategic decision for a strong preference of arguments from authority has to be critically discussed. They use a great number of arguments appealing to the authority of the Bible. All in all, about 80 quotations from the Old and New Testament occur in the text (cf. Schaub 1976, p. 55; on the use of analogies taken from the Bible in other works of Büchner cf. Waragai 1996). This strategy can be criticized as follows: The authority of the Bible is invoked although it is not made clear in most of the passages whether the respective utterances of Jesus Christ, the prophets and the evangelists can be plausibly applied to the historical and political situation of Hessen in the year 1834.

Furthermore, the argumentative appeal for a general uprising of the masses, that is, for the use of violence as a means of politics, is somewhat problematic or even paradoxical, because argumentation normally is a non-violent means for the solution of conflicts. In addition, the sad history of the revolutions tells us that they generally led to new terror and oppression. Finally, the mixture of Büchner’s radically socialist original text and the revision by Weidig is not homogeneous, if not inconsistent, because Weidig’s romantic view of the German emperorship does not really fit with Büchner’s revolutionary perspective. Another tension or even incompatibility is caused by the fact that the appeal to use violence against the ruling elite does not fit with those passages of the New Testament where violence against enemies is explicitly rejected. Typically, however, most of the approximately 80 quotations are taken from the Old Testament.

This criticism suggests that Büchner’s “Landbote” contains a number of fallacies, which all in all would justify a very negative judgment. It could be concluded then, that Büchner’s strategic maneuvering quite often derailed. However, the “Landbote” can hardly be judged according to the standards of a critical discussion in the sense of Pragma-Dialectics. Rather, it has to be judged as another type of text. Within Walton’s typology of argumentative dialogues (cf. Walton 1999: p. 17), it could be classified as a mixture of a persuasion dialogue (= a critical discussion), a deliberation dialogue and a quarrel (Note that also a written monological text like the “Landbote” contains dialogical elements). Apart from resolving a conflict of opinion, which is the goal of a persuasion dialogue, the “Landbote” also suggests to perform political acts on a thoughtful basis (= the goal of a deliberation dialogue) and last not least, to reveal deeper conflicts and to express hidden grievances (= the goal of a quarrel or an eristic dialogue). The resulting use of abusive ad hominem arguments may be of little value for “getting at the truth of the matter”, but it can have “the cathartic effect whereby hidden conflicts or antagonisms can be openly acknowledged by both parties” (Walton 1999, pp. 180f.). And indeed, the highly oppressive rule of the elite, the exploitation and the misery of the masses in Hessen needed and deserved a pungent criticism of the kind Büchner gave in the “Landbote”, because the masses were not able and the moderate opposition was not willing to publish such a radical kind of criticism.

Moreover, apart from the critical observation mentioned above, the “Landbote” also deserves some much more positive comments. Firstly, rhetorically spoken, Büchner/Weidig managed to adapt their stylistic presentation very well to the needs of their audience. Secondly, their two main argumentative strategies, namely, to list empirical-statistic arguments concerning the tax burden of the poor masses and the religious arguments from authority successfully selected the two main topics which could have been successful for persuading the majority of the population. This is also stated explicitly by Büchner in the following text (quoted after Böhme 1987, p. 9, p. 11; Hauschild 2000, p. 33):

Und die große Klasse selbst? Für sie gibt es nur zwei Hebel: materielles Elend und religiöser Fanatismus. Jede Partei, welche diese Hebel anzusetzen weiß, wird siegen. […] Mästen Sie die Bauern, und die Revolution bekommt die Apoplexie. Ein Huhn im Topfe jedes Bauern macht den gallischen Hahn verenden. (And the big class itself? There are only two levers to move it: material misery and religious fanatism. Every party who knows to push these levers, will prevail. […] Fatten the farmers, and the revolution will suffer from apoplexy. A chicken in the pot of every farmer will let perish Gaul’s cock [= the revolution, M.K.])

Therefore, if seen from the perspective of style and efficiency of persuasion, the “Landbote” can even be evaluated as a masterpiece of political agitation which was most suitable for explaining complex political structures to the people in a simple, vivid and highly persuasive way.

Büchner’s radical way of formulating his political criticism is also partially justifiable (or at least explainable) because of the scandalous and disgraceful social conditions in Hessen in the year 1834: censorship of the press, prohibition of political meetings, right to stand for election only for a small rich minority, misery of the farmers and craftsmen, child labour, workdays of up to 18 hours. Finally, Büchner hoped for an almost unbloody overthrow of the ruling elite by an uprising of the masses, although he did not reject violence in principle (cf. Hauschild 2000, pp. 36f.). That he perfectly knew the problems of violent political change is shown by his sober remarks about the bloody terror occurring in the years after the French revolution, which he criticized in the same year 1834 in a letter to his fiancée Wilhelmine Jaeglé (cf. Böhme 1987, p. 9; Hauschild 2000, p. 44).

As far as Büchner’s empirical-statistic arguments are concerned, they are basically sound and acceptable. The sums of the various tax types given in the “Landbote” are based on a source which most probably was not biased, namely the statistics by G.W.J. Wagner from the year 1831. Büchner is also quoting his source quite correctly. Out of the 18 figures given by Büchner, 12 are exactly correct, 5 show little deviations from Wagner, resulting from confusion of decimal places or arithmetical errors. Only one incorrect number cannot be explained in this way. Furthermore, these errors need not be Bücher’s (or Weidig’s), because also August Becker, who copied the original text, or the printer could have been responsible for them (cf. Schaub 1976, pp. 65ff.; Hauschild 2000, p. 55).

5. Conclusion

To conclude, I would like to highlight that with his pamphlet “Der Hessische Landbote”, Büchner created a brilliant piece of political propaganda, which was partially downplayed by the additions of Weidig, but also became somewhat inconsistent through these modifications. The aggressive personal attacks and the dehumanization of the political opponents have to be criticized as abusive ad hominem arguments, but can be partially justified with the incredible misery and the reckless exploitation of the masses by the ruling elite as an outburst of justified indignation. These scandalous social conditions are plausibely criticized by Büchner on the basis of reliable statistical sources. Moreover, the“Landbote” is not only to be judged according to the standards of a critical discussion, as it also has the properties of a quarrel or eristic dialogue.

Taken as a whole, Büchner’s text comes close to later leftist revolutionary rhetoric which intends to overthrow the entire power system by relying on the uprising of the masses, such as the speeches by Rosa Luxemburg. Büchner’s text clearly differs, for example, from Lenins’s revolutionary rhetoric. In his pre-revolutionary speeches, Lenin promised to give the power to the people and to abolish the state, but after the revolution in fact relied on the authoritarian control of the state by the party elite, condemning any kind of democratic opposition (cf. Kienpointner, in print).

And of course, Büchner’s leftist populist appeals, which have no nationalist, let alone chauvinist background (cf. Büchner 1834, pp. 5f. on the French revolution), clearly differ from today’s right wing populist propaganda. This kind of propaganda appeals to national ethnic egoism rather than to the international solidarity of all poor and disadvantaged groups suffering from exploitation (cf. also Weiss 2005, p. 259 on some similarities and differences between right wing (Fascist) and left wing (Stalinist) totalitarian propaganda, including aggressive metaphorical attacks at the political opponents, which were also used by Büchner).

References

Balzer, B. (1992). Liberale und radikaldemokratische Literatur. In: Žmegač, V. (Ed.), Geschichte der deutschen Literatur, Vol. I/2, (pp. 277-335), Frankfurt/M.: Hain.

Böhme, H. (1987). Georg Büchner oder Von der Unmöglichkeit, die Gesellschaft mittelst der Idee, von der gebildeten Klasse aus zu reformieren. In: Katalog der Ausstellung: Georg Büchner (pp. 8-15), Frankfurt/M./Basel: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern,.

Büchner, G. (1834). Der Hessische Landbote. Erste Botschaft. [Offenbach: Preller]. Faksimile des Originals. Beilage zu: Katalog der Ausstellung, 1987, Georg Büchner: Frankfurt/M./Basel: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern.

Dijk, T.A. van (1980). Textwissenschaft. München: dtv.

Doury, M. (2004): La classification des arguments dans les discours ordinaires. In: Langage 154, 59-73.

Eemeren, F.H. van (Ed.)(2002). Advances in Pragma-Dialectics. Amsterdam: SicSat.

Eemeren, F. H. van & R. Grootendorst (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Eemeren, F.H., van/P. Houtlosser (2002a). Strategic Maneuvering with the Burden of Proof. In: F.H. van Eemeren (Ed.), Advances in Pragma-Dialectics (pp. 13-28), Amsterdam: SicSat.

Eemeren, F.H. van/P. Houtlosser (2002b). Strategic Maneuvering: Maintaining a Delicate Balance. In: F.H. van Eemeren & P. Houtlosser (Eds.), Dialectic and Rhetoric: The Warp and Woof of Argumentation Analysis (pp. 131.-159), Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & P. Houtlosser (2003). More about Fallacies as Derailments of Strategic Maneuvering: The Case of Tu Quoque. In: The Proceedings of the IL@25 Conference at the University of Windsor [CD-rom] Proceedings of the IL@25 Conference at the University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario: Univ. of Windsor.

Eemeren, F. H. van, R. Grootendorst & F. Snoeck Henkemans (1996). Fundamentals of Argumentation Theory. Mahwah, N.J.: Erlbaum.

Franz, E. G. (1987). Im Kampf um neue Formen. Die ersten Jahrzehnte des Großherzogtums Hessen. In: Katalog der Ausstellung: Georg Büchner (pp. 38-48), Frankfurt/M./Basel: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern.

Freeman, J.B. (2005). Systematizing Toulmin’s Warrants: An Epistemic Approach. In: Argumentation 19.3, 331-346.

Glebke, M. (1995). Die Philosophie Georg Büchners. Marburg: Tectum.

Hauschild, J. Chr. (1987). »Gewisse Aussicht auf ein stürmisches Leben«. Georg Büchner 1813-1837. In: Katalog der Ausstellung: Georg Büchner (pp. 16-37), Frankfurt/M./Basel: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern.

Hauschild, J. Chr. (2000). Georg Büchner. Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Kienpointner, M. (1992). Alltagslogik. Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog.

Kienpointner, M. (2005). Racist Manipulation within Austrian, German, Dutch, French and Italian Right-Wing Populism, Saussure, L. de, Schulz, P. (Eds), Manipulation and Ideologies in the Twentieth Century (pp. 213-235), Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Kienpointner, M. (In print). Zur Revolutionsrhetorik von Georg Büchner, Rosa Luxemburg und Wladimir I. Lenin. Eine vergleichende Analyse. To appear in: E. Hoffmann et al. (Eds.), Festschrift R. Rathmayr, Wien: Wiener Slawistischer Almanach.

Kopperschmidt, J. (1980). Argumentation. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, Fire and Dangerous Things. Chicago: Chicago Univ. Press.

Lakoff, G. (2005). Don’t Think of an Elephant! White River Junction: Chelsea Green.

Lakoff, G. & M. Johnson (1980). Metaphors We Live by. Chicago: Chicago Univ. Press.

Mannheim, K. (1929). Ideologie und Utopie. Bonn: Cohen.

Mayer, Th.M. (1987). Die >Gesellschaft der Menschenrechte< und Der Hessische Landbote. In: Katalog der Ausstellung: Georg Büchner (pp. 168-186), Frankfurt/M./Basel: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern.

Perelman, Ch. & L. Olbrechts-Tyteca (1958). Traité de l’argumentation. La Nouvelle Rhétorique. Bruxelles: Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles.

Schaub, G. (Ed.)(1976). Georg Büchner, Friedrich Ludwig Weidig: Der Hessische Landbote. Texte, Materialien, Kommentar. München: Hanser.

Toulmin, St. (1958). The Uses of Argument. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ.Press.

Toulmin, St., R. Rieke & A. Janik (1984). An Introduction to Reasoning, New York: Macmillan.

Wagner, G.W.J. (1831). Statistisch-topographisch-historische Beschreibung des Großherzogthums Hessen. 4. Bd. Statistik des Ganzen. Darmstadt: Leske.

Walton, D.N. (1992). The Place of Emotion in Argument. University Park: Pennsylvania State Univ. Press.

Walton, D.N. (1998). Ad Hominem Arguments. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Walton, D.N. (1999). Appeal to Popular Opinion. University Park, Pa., Penn State Press.

Walton, D.N. (2005). Deceptive Arguments Containing Persuasive Language and Persuasive Definitions. In: Argumentation 19, 159-186.

Waragai, Ikumi (1996). Analogien zur Bibel im Werk Büchners. Rankfurt/M.: Lang.

Weiss, D. (2005). Stalinist vs. Fascist Propaganda. In: Saussure, L. de, Schulz, P. (Eds.), Manipulation and Ideologies in the Twentieth Century (pp. 251-274), Amsterdam: Benjamins.

West, E. (1987). Die Lage der Darmstädter Bevölkerung im Vormärz. In: Katalog der Ausstellung: Georg Büchner (pp. 49-55), Frankfurt/M./Basel: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern.