Imaging Africa: Gorillas, Actors And Characters

Africa is defined in the popular imagination by images of wild animals, savage dancing, witchcraft, the Noble Savage, and the Great White Hunter. These images typify the majority of Western and even some South African film fare on Africa.

Africa is defined in the popular imagination by images of wild animals, savage dancing, witchcraft, the Noble Savage, and the Great White Hunter. These images typify the majority of Western and even some South African film fare on Africa.

Although there was much negative representation in these films I will discuss how films set in Africa provided opportunities for black American actors to redefine the way that Africans are imaged in international cinema. I conclude this essay with a discussion of the process of revitalisation of South African cinema after apartheid.

The study of post-apartheid cinema requires a revisionist history that brings us back to pre-apartheid periods, as argued by Isabel Balseiro and Ntongela Masilela (2003) in their book’s title, To Change Reels. The reel that needs changing is the one that most of us were using until Masilela’s New African Movement interventions (2000a/b;2003). This historical recovery has nothing to do with Afrocentricism, essentialism or African nationalisms. Rather, it involved the identification of neglected areas of analysis of how blacks themselves engaged, used and subverted film culture as South Africa lurched towards modernity at the turn of the century. Names already familiar to scholars in early South African history not surprisingly recur in this recovery, Solomon T. Plaatje being the most notable.

It is incorrect that ‘modernity denies history, as the contrast with the past – a constantly changing entity – remains a necessary point of reference’ (Outhwaite 2003: 404). Similarly, Masilela’s (2002b: 232) notion that ‘consciousness of precedent has become very nearly the condition and definition of major artistic works’ calls for a reflection on past intellectual movements in South Africa for a democratic modernity after apartheid. He draws on Thelma Gutsche’s (1972) assumption that film practice is one of the quintessential forms of modernity. However, there could be no such thing as a South African cinema under the modernist conditions of apartheid. This is where modernity’s constant pull towards the future comes into play (Outhwaite 2003). Simultaneous with the necessary break from white domination in film production, or a pull towards the future away from the conditions of apartheid, South Africans will need to re-acquire the ‘consciousness of precedent’, of the intellectual and cultural heritage of the New African Movement, such as is done in Come See the Bioscope (1997) which images Plaatjes’s mobile distribution initiative in the teens of the century. The Movement’s intellectual and cultural accomplishments in establishing a national culture in the context of modernity is a necessary point of reference for the African Renaissance to establish a national cinema in the context of the New South Africa (Masilela 2000b). Following Masilela (ibid.: 235), debates and practices that are of relevance within the New African Movement include:

1. the different structures of portrayal of Shaka in history by Thomas Mofolo and Mazisi Kunene across generic forms and in the context of nationalism and modernity;

2. the discussion and dialogue between Solomon T. Plaatje, H.I.E. Dhlomo, R.V. Selope Thema, H. Selby Msimang and Lewis Nkosi about the construction of the idea of the New African, concerning national identity and cultural identity;

3. the lessons facilitated by Charlotte Manye Maxeke and James Kwegyir Aggrey in making possible the connection between the New Negro modernity and New African modernity;

4. the discourse on the relationship between Marxism and modernity within the context of the Trotskyism of Ben Kies and I.B. Tabata and the Stalinism of Michael Harmel, Albert Nzula and Yusuf Mohammed Dadoo; and

5. the feminist political practices of Helen Joseph, Lilian Ngoyi, Phyllis Ntanatala and others.

In the building of a South African national cinema, therefore, it is imperative that South Africa’s new phase of modernity does not deny history but seeks to situate South African film practice and film scholarship within African film history, where they naturally and historically belong, rather than in only European or Hollywood film history, as Eurocentricism and supremacy have attempted to impose them (Masilela 2000b: 236). This task of indigenisation is one that I have set myself for this book for, as Masilela argues:

Although the context of 1994 represents a political triumph, it is questionable whether it has been accomplished by commensurate intellectual and cultural achievements. Our present is the reverse mirror of the past of the New African Movement. In this light it is all the more necessary for the African Renaissance to establish a dialectical connection between past and present (ibid.: 234).

Romancing Africa

Africa is considered in the popular imagination to be an undeveloped continent, a contemporary representation of humankind’s ‘past’. The continent has been an enormous source of mythical imagery since the birth of the film industry in 1885. The readable, engaging, and often irreverent Africa on film: Beyond black and white, by Kenneth Cameron (1994), charts and evaluates recurring patterns of such representation by American, British and some South African films. Amongst the recurring patterns are:

1. the presence (or more noticeably, the absence) of women, both black and white;

2. the recurrence of the Great White Hunter, a classless individual who often represents counter-racist tendencies;

3. Imperial Man, who represented British governing confidence during the colonial era;

4. the Good African, Imperial Man’s trusting and doting servant; and

5. American self-aggrandisement via a male landscape. In these ‘jungle movies’ negative images of black women and race hatred are a speciality.

A key contributor to myths of Africa in both British and American fantasy films was the nineteenth century South African-based British novelist H. Rider Haggard. He exported bizarre descriptions of Africa and Africans, writing about volcanoes, treasures, hunter-heroes, demonic black witches, lost white civilisations, white goddesses, and so on. These images reappear in endless remakes of his books on film and television, and they are imported into other titles and media as well. Films like Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), now a Disneyland ride, for example, to some extent derive their imagery and characters from writers like Haggard. Contemporary images of Africa found in world cinema are thus inextricably linked to the nature of the encounter between early writers and this mysterious continent. Many such writers were based in South Africa during the late nineteenth century.

Another key historical influence on images of Africa came from the pen of American Edgar Rice Burroughs. Burroughs’s twin sources for Tarzan were Haggard and Rudyard Kipling, writer of the famous Jungle book (Cameron 1994: 32). Tarzan is cast as a ‘noble savage’, an exemplar of an aristocratic British bloodline, in many early Tarzan films, and in the much more nuanced Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan Lord of the Apes (1984). The American interpretations eliminated Tarzan’s aristocratic imperial origin and made him ‘American’. As an American, Tarzan expresses white Americans’ racial fear of blacks. The American Tarzan films are a depression-era fantasy, and those featuring Jane provide narratives of a stable couple in which the husband is stronger than the chaotic forces of life (ibid.: 43).

The role of monkeys and gorillas is also instructive in the Tarzan and other films. My experience in talking to primary school children at two schools in Indiana, Pennsylvania in March 1996, bears this out. One class of 10/11-year-olds had formed their impression of Africa with the help of PG-rated films such as Congo (1995), Outbreak (1995) and Jumanji (1995). Africa for them was a jungle inhabited by diseased gorillas and monkeys that threatened Americans’ health! Once they had succeeded in obtaining an admission from me that monkeys indeed visited my garden in Durban, no explanations contradicting their stereotypes could repair the damage done. (I explained that Durban is sub-tropical, our gardens have wild bananas and other fruit and that monkeys were being displaced by massive urbanisation – no one looks out for monkey’s rights!) My daughter, who started high school in Michigan in 1998, came up with the defensive analogy that ‘squirrels are to East Lansing what monkeys are to Durban’, as we had previously only seen these small furry creatures as comic book characters. However, once she admitted the fact of monkeys in our garden, the moral high ground could not be retrieved, despite the analogy. Now that one theory on the origin of Aids is sourced to transmission between chimpanzees and humans, Africa again becomes associated in the United States (US) with incurable globalising pandemics. Muhammed Ali’s ‘Rumble in the jungle’ (where he fought George Foreman for the world heavyweight boxing title) owes its origins to the kinds of films set in Africa which shaped the early American imagination.

In the late 1940s after he became a little too saggy to fit into a Tarzan loincloth without depressing popcorn sales among cinema audiences, the great Johnny Weismuller filled the twilight years of his acting career with a series of low budget adventure movies with titles like Devil Goddess and Jungle Moon, all built around a character called Jungle Jim. These modest epics are largely forgotten now, which is a pity because they were possibly the most cherishably terrible movies ever made … My own favourite, called Pygmy Island, involved a lost tribe of white midgets and a strange but valiant fight against the spread of communism. But the narrative possibilities were practically infinite since each Jungle Jim feature consisted in large measure of scenes taken from other, wholly unrelated adventure stories. Whatever footage was available – train crashes, volcanic eruptions, rhino charges, panic scenes involving large crowds of Japanese – would be snipped from the original and woven in Jungle Jim’s wondrously accommodating story lines. From time to time the ever-more fleshy Weismuller would appear on a scene to wrestle the life out of a curiously rigid and unresisting crocodile or chase some cannibals into the woods, but these intrusions were generally brief and seldom entirely explained (Bryson 2002: 1-2).

Bill Bryson (ibid.: 2) thrusts the point home: What is especially tragic about all of this is that I not only watched the movies with unaccountable devotion, but also was incredibly influenced by them. In fact, were it not for some scattered viewings of the 1952 classic, Bwana Devil, and a trip on a Jungle Safari Ride at Disneyland in 1961, my knowledge of African life, I regret to say, would be entirely dependent on Jungle Jim movies.

The later Greystoke restores Tarzan’s British lineage, while simultaneously revealing aristocratic viciousness, and Tarzan’s escape from it, by returning to the wild, back to his gorilla family, and a social and environmental integrity long lost to the West. While Burroughs never set foot in Africa, Tarzan visited South Africa in a television series (1997) shot at Sol Kerzner’s Lost City, part of the Sun City hotel, casino and entertainment complex that became infamous for boycott busting during the 1980s by international music celebrities who performed there. Black South African actors on a promotional television programme, which preceded the television series, insisted that ‘this is the real Africa’. Their PR came to mind when I visited the Disneyland feature of the Tarzan Tree House under attack from a gorilla, which in 2004 seemed to have replaced the more stable Swiss Family Robinson set. These actors thus undermined nearly a century of African criticism of the racist dimension of the bulk of the Tarzan genre. However, as Rob Gordon reminds a forum of documentary filmmakers, audiences do not always assume the imperialism of the director or characters as

… the meaning of race (and of culture) is ultimately a matter of local grass-roots interpretation. The most striking example here is Rambo, a film which most of us would find offensively imperialistic. Yet it’s a hit in Vietnam and among Australian Aborigines because they see Rambo as fulfilling important kinship obligations and fighting an obstinate bureaucracy. Rambo is currently the training film of choice for the sad child soldiers of Sierra Leone. So too, on the South African platteland [‘countryside’] Tarzan was popular, not because it reinforced notions of white superiority (although it undoubtedly did) but because the audiences loved to find fault with the film’s representation of Africa. Let us always be aware that every production has unanticipated consequences (cited in Tomaselli 2001).

South Africa: Protecting its own

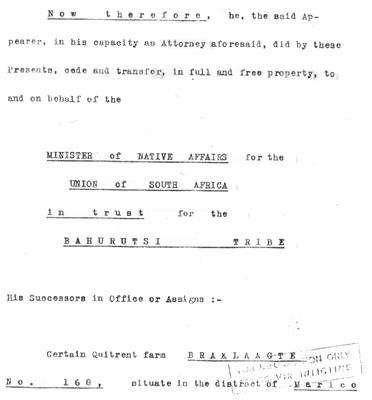

In 1995, cinema in South Africa was exactly one hundred years old. Early projection devices were frequented around the Johannesburg goldfields from 1895 onwards (Gutsche 1972). The first cinema newsreels were filmed at the front during the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) by the British Warwickshire Company. Others simply fabricated the war scenes in England itself. The world’s longest-running weekly newsreel, African Mirror (1913-1984), was in the mid-1980s broadcast as history on national television. The first ever South African narrative film was The Kimberley Diamond Robbery, made in 1910.

Between 1916 and 1922, I.W. Schlesinger produced forty-three big-budget technically high-quality features. Schlesinger had arrived penniless on South African shores from America at the turn of the century and proceeded to build an international insurance empire from Johannesburg. In 1913, he consolidated total control over the South African entertainment industry – theatre, cinema, and later radio (Gutsche 1972). The cinematic themes and images chosen by Schlesinger were rooted in the ideological outlook of the period prevalent in European and Anglo-American culture. Haggard’s novels were a recurring source for film scripts, and continue to be so a century later.

In Schlesinger’s own historical epics, Boer and Briton stood together under the flame of unity and civilisation against barbaric black hordes (e.g. De Voortrekkers / Winning a Continent, 1916 and Symbol of Sacrifice, 1918). Though De Voortrekkers was the model for the later American epic, The Covered Wagon (1923), it was the sheer magnitude of Symbol of Sacrifice, with its 25 000 Zulu warrior extras, that set early technical standards for this genre. Foreign productions such as Zulu (1966) and Zulu Dawn (1980), docu-dramas based on the British-Zulu Wars of 1879, followed Symbol of Sacrifice. These films continued the West’s fascination with the Zulu, mythologised in the South African television series and US cable hit, Shaka Zulu (1986) (Tomaselli 2003; Shepperson and Tomaselli 2002).

Production declined after 1922 because, despite high technical standards, obtaining footholds in British and US markets proved difficult. However, unlike other countries, the South African film industry remained in local hands until 1956, when 20th Century Fox bought out most of Schlesinger’s cinema interests, including the Killarney Films production house. In 1969 the South African-owned Ster Films bought Fox’s South African holdings and retained near monopolistic control of the industry until the mid-1990s, when it sold its interests to another South African group, Primedia (cf. Tomaselli and Shepperson 2000). This unusual situation of very long periods of domestic ownership resulted in South African producers enjoying some leverage with the local distributors and exhibitors when it came to securing screen access for their films.

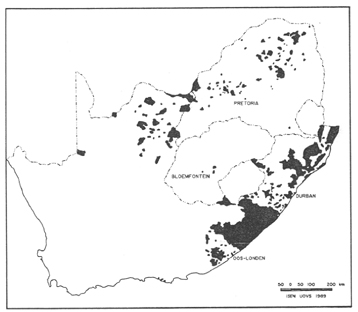

A thirty-year lull was broken in the early 1950s by Jamie Uys (of The Gods Must be Crazy, 1980; 1989 films) when he succeeded in attracting Afrikaner capital to establish independent production. In 1956 he represented a consortium of producers in persuading the government to provide a subsidy for the making of local films. This subsidy was modified through the years and continued until the late 1980s. The subsidy was paid against a percentage of box office income and deliberately favoured Afrikaans-language films over English. Later, in 1975, a specific subsidy was also introduced for films using black South African languages (Tomaselli 2000b; Murray 1992). The subsidy system was terminated at the end of the 1980s, and as was discussed in Chapter 3, a new system was introduced in 2004.

It was the government subsidy that resulted in films supportive of the military such as Kaptein Caprivi (1972), made while the South African Police (SAP) propped up the white Rhodesian regime. One of the sub-genres within these ‘jeep operas’ is what Cameron (1994: 145) calls the ‘mercenary film’, such as Wild Geese (1977). These kinds of films reveal clear racism on the part of their directors, as a handful of usually ageing American and British actors playing mercenaries wipe out hundreds of pursuing blacks. The myth of the mercenary remained strong amongst older whites in Africa, rekindled by the idiotic exploits of French, English and South African has-beens in the late 1980s, early 1990s and 2004 with regard to their aborted attempts at coups d’état in the Comores Islands, Seychelles, Equitorial Guinea and elsewhere. These continuing escapades indicate a residual pattern of destabilisation of African countries during apartheid and the Cold War. Mercenaries, ‘dogs of war’, to use Frederick Forsyth’s (1974) term, conducted the work of Imperial man in the twentieth century, taking on communism, barbarism and rescuing all manner of victims of the ‘dark continent’.

Where the Great White Hunters are a social and sexual ideal, as in Out of Africa (1985), the anachronistic young and old fools in Jeeps are nostalgic throwbacks to mythical cinematic times when a few white (and black) mercenaries armed with machine guns could control an entire continent. Indeed, one soldier/actor/mercenary, Simon Mann, arrested with sixty mercenaries in Zimbabwe in March 2004, had even played the role of a parachute regiment colonel in Bloody Sunday (2002), a re-enactment of the 1972 massacre of thirteen Northern Ireland demonstrators by British troops (Sunday Times, 14 March 2004: 6). Antoine Fuqua’s film on African genocide turned into another mercenary-type film, owing to pressure from the film’s star, action hero Bruce Willis, and the production studio, who were hoping to outdo their 2001 success, Black Hawk Down (2001). The result, Tears of the Sun (2003), is an action film with a humanitarian angle, resembling the American western. Bruce Willis plays a Navy SEAL sent to rescue a mission doctor – the female love interest (Monica Belluci) – in Nigeria, which has come under military rule. After witnessing the brutality of the rebel forces, the hero undergoes a change of conscience and decides to help the villagers leave the mission station to the safety of a neighbouring country, thereby putting his own life at risk. The film once again portrays America as the world’s saviour (Bruce Willis’s character at one stage remarks that ‘God already left Africa’), at a time in world history when US intervention in Iraq was a contentious subject.

Afrikaner concerns

While many subsidy-driven films were of appalling quality, rarely returning their costs, those made by Jamie Uys were always box office successes. In large measure, Uys’s grasp of the rural Afrikaners’ taste in humour benefited from the relative lack of alternative sources of entertainment before the advent of television in South Africa in 1976. His comedic themes, which usually made fun of inter-ethnic rivalries, especially those between English-speakers and Afrikaners, consistently outperformed titles from Hollywood. Uys’s studio, in fact, provided a training ground for young Afrikaans-speaking directors, scriptwriters and technicians, who later contributed to the development of the conflict-love genre. These films engaged social issues via genre structures, and are much less conspiratorial than commentators like Peter Davis (1996) would have us believe.

Where international films on Africa and South Africa have tended to ignore women, the insider-outsider genre, wrapped up in a conflict-love plot, consistently depicted headstrong females. Cast as boeredogters (‘farmers’ daughters’, daughters of the earth), these femmes fatales traumatically broke with the tradition and close social and community cohesion centred on ‘the farm’, ‘family’ and volk (‘nation’) as propagated by Rompel (1942a; 1942b). Rather, and with the directors’ approval, they sought their uncertain futures in the sinful city populated by the victorious English enemy. The boeredogter’s relocation heralded the onset of Afrikaner cultural modernity. The cities were where the real political and economic struggles between English and Afrikaner were occurring and where Afrikaner power was negotiating its ascendancy. The boeredogter indicated the strategic need for Afrikaner nationalists to secure their interests in this new ideological and economic battleground.

The boeredogter storylines captured the imaginations of the Afrikaner public and, more recently, the rise of South African actress Charlize Theron to Oscar-winning success can be likened to the plots of these earlier films. Theron, who apparently said in an early interview that she left South Africa when apartheid ended for fear of not being able to find a job as a white person, was raised on a smallholding on the outskirts of a working class part of the country. After a brief modelling stint, which included her baring her breasts for the editor of the South African edition of Playboy magazine, she moved to Hollywood with her mother, dropped her accent in favour of an American drawl, and worked her way to the top, ultimately gaining Oscar recognition for her performance in Monster (2003). Her Golden Globe award acceptance speech played on this romanticised rags-to-riches tale when she cried, ‘I’m just a girl from a farm in South Africa!’ In her Oscar acceptance speech, Theron thanked ‘everybody in South Africa’ and promised to ‘[bring] this [the Oscar] home next week’. To many proud South Africans, this was a sign that she was acknowledging her cultural roots despite her American accent. The media hype that surrounded her visit ‘home’ highlights the African inferiority complex when it comes to cultural production, where the ultimate measure of success is to ‘make it overseas’. ‘Making it overseas’ is the equivalent of the boeredogter ‘going to the city’, a necessary though culturally alienating social trajectory in class struggle and personal emancipation from the tyranny of the Community. Theron, for example, travelled with an entourage, her itinerary was kept secret, and she was pressed for interviews by the media. South African Airways donated her and her entourage the first-class cabin, and both President Thabo Mbeki and former President Nelson Mandela met her in person to thank her for ‘putting South Africa on the map’. Theron is now considered South Africa’s most successful film export, thereby dislodging Jamie Uys. This is the fate that awaited the boeredogter in the earlier genre – success results in cultural distance, enculturation into an alien environment, and consorting with the enemy. Theron’s achievement is secured at the expense of, but on behalf of, the group, Afrikaner culture and economy. Theron has adapted herself to suit Hollywood standards: even her dress and styling on Oscar night made deliberate reference to the Hollywood sirens of yesteryear, appealing to American femme fatale iconography. (However, in fairness, the local industry is perhaps not able to support many actors and actresses, especially those after big-budget box office success.)

Intercultural mediations

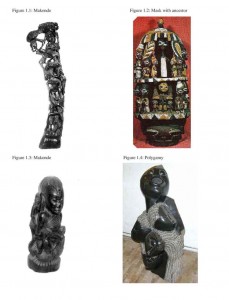

Intercultural conflict underpins many a South African film. For instance, the sympathetic treatment of the conflict between Roman-Dutch and African Customary Law is the theme of Uys’s Dingaka (1964). Commentators such as Mtutuzeli Matshoba and John van Zyl recognised at the time of the film’s release a cultural authenticity in the film (cited in Tomaselli 1988: 134). Dingaka (which means ‘traditional healer’) was the first South African film made in Panavision, and it introduced actor Ken Gampu to the world. The story begins in a remote and tropical African village where two men are publicly engaged in a stick fight. The resentful loser of the fight, Masaba, seeks the help of the village traditional healer, who tells him that in order to regain his stick-fighting prowess, he needs to eat the heart of a twin child. When a twin from the village disappears, father Ntuku (played by Gampu) sets out to find Masaba, who has fled to the city.

From here the plot revolves around Ntuku’s experiences in the city: he is conned out of his money and forced to find work in the mines. Here he encounters and attacks his rival and is subsequently arrested. At this point the white male lead, legal aid lawyer Davis (Stanley Baker), enters the plot. After failing to convince Ntuku to follow legal procedure and accept his professional services, Ntuku is imprisoned for again attacking Masaba (Paul Makgoba), this time in open court. Ntuku escapes from prison and Davis and his wife (Juliet Prowse) travel to his village to seek him out. At the village, Davis urges Ntuku to kill the sangoma (‘traditional healer’, played by John Sithebe), who is ‘only a man’. Amid the sounds of thunder, Ntuku eventually does so, despite fearing the wrath of the gods, and peace is restored, ‘proving that [Davis’s] white-European rationalism was correct: the “witchdoctor” is only a man, and he has no magical power’ (Cameron 1994: 125).

The film is severely criticised by Davis (1996) for its unrealistic and overly stylised portrayal of African village life, which glosses over the realities of apartheid inequalities as they were experienced in everyday life. He objects to the film’s racially patronising and binaristic depictions of African people and their spiritual beliefs (in particular the stereotypically ‘evil’ sangoma), which reveal ‘a syncretising of apartheid’s delusions’ (ibid.: 66). He points to Uys’s Nationalist political leanings, and the apartheid legislation that was being enacted at the time, to further his point. During the 1960s, the apartheid government developed a scheme to replace the traditional leaders in the tribal homelands with appointed Bantu Authorities, ‘puppets who would dance on the government’s strings’ (ibid.: 67). For Davis, this suggests that ‘what is being played out in Uys’s melodrama of African life is very much an unconscious metaphor for what was happening over the broader landscape of South Africa – the overthrow of not only the traditional but the popular leadership of the African people’ (ibid.: 68).

While the film does have the mandatory African travelogue feel in places, as required by the US market, it offered a thematic breakthrough at the time with regard to the portrayal of the African encounter with Western tenets of justice, and also in terms of depicting an interracial friendship. The white layer, the bearer of Roman-Dutch Law, is by no means Imperial Man, and the black character, Ntuku, is no-one’s doting servant. While ‘white justice’ rules, ‘black justice’ is revealed as being less impersonal. As Van Zyl concludes in his review in The Chronicle: ‘This is the stuff of Nordic sagas, and all credit is due to Jamie Uys and Ken Gampu for pulling it off. It hardly matters that an “impression” of an African tribe was created which can be faulted by ethnologists’.

Cinematic treatments of the San (or Bushmen) have indicated a different encounter with white South Africans to that of the Zulu, or with regard to traditional law. The remote, unforgiving Bushmen in Lost in the Desert (1971) are very unlike the endearing characters Uys constructed in his Gods Must Be Crazy pseudo-documentaries (cf. Tomaselli 2006). In propaganda movies, men, the patriarchal stalwarts, are well served by their submissive women. In the conflict-love genre they betray their men. In Uys’s films they are either absent or bemused by the anxiety and ineptness with which suitors interact with them. While foreign anti-apartheid critics have not always been kind to Uys’s few international releases, especially Dingaka and the first two Gods Must Be Crazy films, they did provoke discussion about race and racism of a kind which also left its mark on debates in South Africa (Davis 1996; Blythe 1986). More relevantly, these films were negotiating ways of approaching intercultural relations at a time when racial conflict had hardened into the intractable binary frame which characterises much of Davis’s analysis.

In contrast to the kind of politically correct critique that characterised attacks on the two Gods Must Be Crazy films, Cameron (1994: 155) argues that these titles reject the more pervasive stereotypes of jungle, savage dancing and witchcraft which typify the majority of Western film fare on Africa. The Gods Must be Crazy (1980), in theme, narrative structure and comedic device is very similar to Uys’s earlier films in which people of colour hardly featured at all. He basically repeated the story he made of himself and his family in his first amateur film, Daar Doer in die Bosveld (‘Far Away in the Bushveld’ – 1951), and embroidered it in each retitled and more technically sophisticated reincarnation in a different environment over the period of his forty-year career.

Key to the Uys idiosyncratic intertext is the lead male Afrikaner character’s awkwardness with women, inter-ethnic Afrikaner-English rivalry, and a preference for pastoralism. Uys, as an interpreter of Afrikaner foibles and social anxiety, thus inaugurated a set of peculiarly South African themes. These drew on Buster Keaton’s films, where machines seem to have minds of their own and engage in all kinds of bizarre, uncontrollable and unpredictable behaviours. Machines are products of modernity, itself a mystery to ruralites. Uys sensitively highlighted Afrikaner anxiety of entering into modernity through using these machines (vehicles, winches, etc.) as metaphors for social and cultural insecurity. Pastoralism was held to be the protector of pure Afrikaner identity in the face of uncertainty brought about by massive industrialisation where ‘self conscious’ machines could herald the destruction of traditional societies. Uys’s use of machines as Keaton-type comedic devices subverted via slapstick the previously dominant images of die Boer (‘farmer’/Afrikaner), created by Afrikaners of themselves in their propagandistic amateur feature films of the 1930s and 1940s.

People defining themselves as Afrikaners are known for a certain austerity. Uys’s early cinema offered the first light-hearted self-depreciating cultural moment after the severity of the historical processes this group is historically known for, as it attempted to be humourous rather than overtly ideological in its approach. His self-depreciating humour was continued in the 1990s by Afrikaner comedian Leon Schuster whose racial politics shift as fast as does the political landscape in films like Oh Shucks, Here Comes Untag (1990), Sweet ’n Short (1991), Panic Mechanic (1997), Mr Bones (2001) and Mama Jack (2005). All these films, from a variety of directors, interrogate white Afrikaner fears about a Mandela ‘black government’ and white loss of political control. Slapstick and, increasingly with Schuster, a narratively developed Candid Camera genre, denotes one trajectory in post-apartheid cinema (cf. Steyn 2003). A clear introspection and engagement of South African themes such as in Chikin Biznis (1998), Shooting Bokke (2003), and E’skia Mphahlele (2003) accounts for another more culturally serious post-apartheid trajectory.

Another film in the Schuster-type genre, written by Mfundi Vundla and directed by David Lister, is Soweto Green (1996) with John Kani playing the returned exile. There’s a Zulu on my Stoep (1993), written by and starring Schuster, was one of the few in the genre that effectively interrogated racial issues via blackface casting and identity exchange. A promising start, where the returned black exile (John Matshikiza) switches identities with his early white boyhood friend to outwit their friends whose car they have stolen, degenerates into over-the-top slapstick chaos. Slapstick heaven also mars the conclusion of Soweto Green. Is it possible that this idiotic chaos was a metaphor for political times to come?

International African actors and voices

Films set in Africa provided opportunities for black American actors such as Paul Robeson, Sidney Poitier, James Earl Jones, Denzel Washington, Danny Glover and Morgan Freeman, to redefine the way that Africans are imaged in international cinema. Cameron (1994: 182) mentions the later films of Robeson especially, who brought dignity to his roles, and created spaces for African female characters to emerge in their own right. South African singer Miriam Makeba, for example, shot to international fame in Lionel Rogosin’s Come Back Africa (1959) (cf. Balseiro 2003). Another vehicle to an international career for a South African was Zoltan Korda’s Cry the Beloved Country (1951), based on Alan Paton’s novel. Lionel Ngakane made his name as a supporting actor alongside the lead played by Poitier (cf. Ngakane 1997). The contribution of Michael and Zoltan Korda to the British image of Africa was less racist than contemporary American representations, and Zoltan’s break with Empire stereotypes of both British and blacks in Cry the Beloved Country challenged the industry internationally to rethink its representations of Africans in cinema. Davis (1996: 2), however, notes the deep influence of imperialist literature on Zoltan Korda who later made Sanders of the River (1935), Elephant Boy (1937) and Four Feathers (1939), ‘all of them celebrating heavily romanticised aspects of white rule’. However, as Hees (1996: 178) observes:

This may be true, but Zoltan Korda also directed and himself produced Cry, the Beloved Country (1951), a version of Paton’s novel totally lacking the sentimentality of Darrell Roodt’s more recent version; the other films mentioned were produced by his brother, Alexander Korda. I am not making a point here about the factual content of Davis’s book, but rather expressing a concern about its tendency to present material in a way that reduces racial issues to white exploitation of victimized blacks.

Very little has been written on the contribution of actors in South African cinema. Ken Gampu, who starred in Dingaka, gets a brief but long overdue mention from Cameron (1994: 124) as a great performer. Gampu’s interpretation of the roles into which both South African and international directors had cast him generally lifted the tenor of the films in which he acted. In contrast is Richard Rowntree’s Shaft in Africa (1973), with its blaxploitation characters in which Africa was merely a convenient backdrop to American storylines. Such was the popular impact of the Shaft films in South Africa, however, that a beer label and some shops briefly named themselves thus.

Even less has been written on female South African film directors and actors, some of whom have also doubled up as directors. Entries in The feminist companion guide to cinema including Katinka Heyns, Helen Nogueira and Elaine Proctor are offered by Ruth Teer-Tomaselli and Wendy Annecke (1990). Heyns, directed by Jan Rautenbach, played particularly significant roles in Afrikaans cinema that critically interrogated Afrikaner bigotry and political expediency (e.g. Wild Season, 1968; Katrina, 1969; Jannie Totsiens, 1970 and Pappalap, 1971). Heyns later directed films that continued this thematic analysis in Fiela se Kind (‘Fiela’s Child’) (1987), and Paljas (‘Clown’) (1997).

Cinema as the voice of the people is much younger than cinema the institution. That voice was facilitated by producers located elsewhere in films like Cry the Beloved Country and the clandestinely shot, chilling docu-drama Come Back Africa, which reveals the brutality of apartheid’s structural violence in the psychological breakdown of its central protagonist Zacharia (Zachariah Mgabi) (cf. Balseiro 2003; Beittel 2003). Later, Euzhan Palcy’s A Dry White Season (1989, based on the novel by Andre Brink) and Richard Attenborough’s Cry Freedom (1987, based on the friendship between journalist Donald Woods and slain black activist Steve Biko) were the first films to bring the horrors of apartheid repression to the big screen and cinema audiences on a mass scale not previously achieved.

These international and other productions employed South African actors such as Zakes Mokae, amongst others. Lionel Ngakane made his mark as a director with the British-made, award-winning Jemina and Johnny (1966), a short cinematic statement on non-racialism, which followed his documentary on apartheid, Vukani Awake (1964). Ngakane served as technical consultant on A Dry White Season. Ngakane, who died in late 2003, however declined an invitation from producer Anant Singh to act in the Darrell Roodt remake of Cry the Beloved Country (1995) due to other commitments. Ngakane’s influence on African cinema through his involvement with the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI) (while he was in exile) that occurred after finishing the Korda film was significant. This pan-African work was recognised in 1997 when Ngakane was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by the University of Natal. He had earlier been awarded a lifetime Achievement Award by the M-Net Film Awards on which he was also a consultant for its New Directions short film series.

Between 1956 and 1978 genre films (especially in Afrikaans) earned higher returns than did imported Hollywood fare. Exceptions which interrogated apartheid exposed white South Africans to new critical styles. Amongst these was the unique expressionism of Rautenbach’s Jannie Totsiens, in which a psychiatric asylum inhabited by white inmates is an allegory for apartheid. A thin, comedic neo-realism is found in Donald Swanson’s African Jim (1949) and Magic Garden (1961), both of which emphasise black characters and stories in urban settings. The more obviously bleak neo-realist style of Athol Fugard and Ross Devenish is evident in Boesman and Lena (1973), The Guest (1978) and Marigolds in August (1980). These are films with tortured characters, whose angst is perhaps of a more existential origin than of apartheid. Fugard’s last film, Road to Mecca (1992), directed by Peter Michel, is his best yet. Its swirling camera which focuses on interpersonal relationships between an old, eccentric, secluded white artist and her hostile small-town conservative Afrikaner community (based on Helen Martin of ‘the owl house’ fame, Nieu Bethesda), reveals the inner Fugard, a solitary artist also alienated from the society in which he then lived.

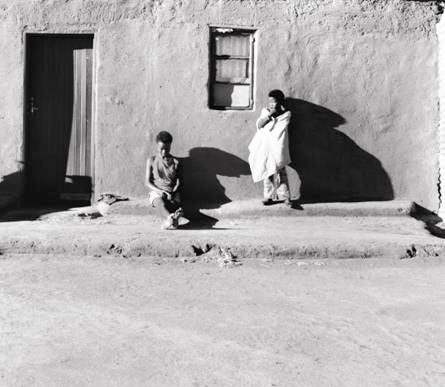

The first domestic black-made film was theatre director Gibson Kente’s How Long (must we suffer …?) (1976). It was shot in the Eastern Cape during the Soweto uprising. How Long was briefly shown in the Transkei Bantustan. The whereabouts of the print are unknown. Other films made by whites and aimed at blacks tended to be appallingly inept, exploitative and patronising, such as Joe Bullet (1974), which kicked off the South African blaxploitation genre. This marginalised sector of the industry literally consisted of butchers, bakers and candlestick makers. It emerged in 1974, milked the government subsidy pot dry, and collapsed at the end of the 1980s (Murray 1992; Gavshon 1983; Tomaselli 1988).

However, black director and actor Simon Sabela, employed by Heyns Films, injected a degree of cultural integrity into the films he made, such as U-Deliwe (1975). It was only towards the end of the 1980s when it became known that Heyns Films had been secretly infiltrated, Nazi-style, by the apartheid government, which was responsible for funding Sabela’s films, though this was not known by him. The contradictions are clear – even state-sponsored films had a degree of integrity of content, in contrast to the blatantly opportunistic racism of many of those privately financed low-budget films made by some whites for the ‘black’ market, and funded via post-release subsidy claims made by their makers. Such films sometimes consumed less than a weekend in production time.

Emergent anti-apartheid cinema

White South Africa, observes Cameron (1994), tends to see itself as a reflection of white American values; hence the obsession with Theron and to a lesser extent Arnold Vosloo, star of The Mummy (1999; 2001) films. Breaking with these values indicates to Cameron a maturing of South African cinema as seen particularly in the post-1986 anti-apartheid films directed by Roodt such as Place of Weeping (1986), Jobman (1989), City of Blood (1986), Sarafina (1993) and the Cry the Beloved Country remake starring James Earl Jones. Anant Singh, a South African of Indian extraction, produced these films, and many others. His activities extend to the US, one of his most technically sophisticated being The Mangler (1994), based on a Stephen King novel.

The years following 1986 saw the sustained development of a domestic anti-apartheid cinema financed by capital looking for tax breaks and international markets, mainly driven by Singh’s financing. Simultaneous with this emergent oppositional trend, Canon Films responded with a new wave of Haggard’s explorer titles like King Solomon’s Mines (1985) and Alan Quartermain (1987), before eventually going out of business (see Yule 1987). The 1980s saw host to over 800 foreign-made films in South Africa during this time, all pursuing loopholes in South African tax law. South Africa offered relatively cheap, but highly sophisticated technical labour, which was a deciding factor in the use of South African locations and facilities. Ninjas in the Third World, voodoo killings, psychotics and other themes also emerged from South African directors during this time (Taylor 1992).

Multiracial teams have made films such as Mapantsula (1988) and Hijack Stories (2002), both directed by Oliver Schmitz, Ramadan Suleman’s Fools (1997), Wa Luruli’s Chikin Biznis (1998) and Les Blair’s Jump the Gun (1996). Productions like these have for the first time given South Africa a sustained and sophisticated examination of the full spectrum of South African history and everyday life. These examinations include:

1. Historical dramas, for example Boer prisoners held by the British during the Anglo-Boer War in Dirk de Villiers’s Arende (‘The Earth’, 1994), cut into a feature from the SABC-television series, and Manie van Rensburg’s The Native who Caused all the Trouble (1989). Also see De Voortrekkers/Winning a Continent (1916), Bloodriver (1989), Zulu Dawn (1980), amongst others;

2. Films depicting the liberal opposition to apartheid that occurred in the 1960s, for example, Sven Persson’s Land Apart (1974), Broer Matie (1984), Chris Menges’ A World Apart (1988), Roodt’s 1995 remake of Cry the Beloved Country, Cry Freedom and A Dry White Season;

3. The psychological impact on white South Africans of the wars waged against South Africa’s neighbours, for example Roodt’s The Stick (1987) and urban violence in City of Blood. These are films about pathology as normality. Opposed to the psychological analysis offered by these films were the jeep operas like Kaptein Caprivi, Grenbasis 13 (1979) and the two Boetie Gaan Border Toe (1987; 1988) films directed by Regardt van den Bergh;

4. The popular anti-apartheid struggle of the 1980s was imaged in Mapantsula, Sarafina, Place of Weeping, Bopha (1993), the BBC’s Dark City (1989) and scores of documentaries. Land Apart, which predicted the Soweto uprising of June 1976, provided a benchmark for anti-apartheid documentaries made within South Africa. Nana Mahamo’s Last Grave at Dimbaza (1973), shown clandestinely throughout South Africa during the 1970s, offered South Africans a very different, indirect address style of documentary. The 1980s in particular saw many more, for example, Jurgen Schadeberg’s Have You Seen Drum Recently? (1988) recreated the energetic days of Drum magazine of the 1950s. Many others have contributed to a growing movement of critical and historically sensitive film and video makers;

5. Comedic films critical of white racial attitudes and experiences, for example, Taxi to Soweto (1991), Soweto Green, Panic Mechanic and There’s a Zulu on my Stoep;

6. Both the historical origins and the contemporary effects of apartheid are found in Procter’s Friends (1994), Heyns’s Fiela se Kind, and Van Rensburg’s The Fourth Reich (1990), constituted into a cinema release from the four-part television series. Andrew Worsdale’s Shot Down (1990) reveals the inner turmoil of South Africans of various races as a consequence of apartheid (see Savage 1989b).

Signposts towards post-apartheid cinema

The future of South African cinema was established in the 1920s. A short film, directed by Lance Gewer, Come See the Bioscope (1997), based on Plaatje’s endeavours to bring the visual technologies of modernity to black South Africans, signposts this post-apartheid revisionist aim. The film is set in 1924, by which stage Plaatje, founding member of the New African Movement and first secretary of the African National Congress (ANC), was already a well-educated and well-travelled politician, historian and author. After returning from his travels, Plaatje toured the country for several years using sponsored equipment (a Ford motor car, a generator and film projector) to educate people in both towns and rural areas about the New Negroes in the US and the unfolding political situation in South Africa (Masilela 2003). Just as Plaatje pioneered mobile cinema distribution, so have many filmmakers since, ranging from the producers of features ‘made for blacks’, through HIV educational movies such as the STEPS for the Future series, to Roodt’s Yesterday (2004). Development of audiences is a major project of the Film Resource Unit based in Johannesburg.

Come See the Bioscope depicts Plaatje (Ernest Ndlovu) as an inspiring leader and educator who takes on the role of ‘the bioscope man’ in order ‘to show people a world they do not know’. Plaatje appreciated early on the powerful role that cinema could play in propagating and shaping beliefs: he protested outside the Johannesburg Town Hall at the showing of The Birth of a Nation (1915), asking why such an anti-black film, banned in some parts of the US, could be shown in South Africa (Masilela 2003: 21). Although the film itself could be criticised for being a somewhat sentimental portrayal, it is a well-made account of how an influential black leader overcame political obstacles and distribution constraints in order to expose black people to cinema, and in so doing educate them about their situation in relation to American developments. Come See the Bioscope brings to life a significant and previously neglected episode in South Africa’s cinema history.

Most documentary crews working in the Plaatje vein work with subjects and sources as ends in themselves, rather than as means to ends. Everyone, prostitutes, street children, gangsters, people with AIDS, villagers, torture victims, experts and others, are all revealed to have personalities, identities and feelings. They are seen to have hopes, fears and disappointments. I call these encounter videos – ‘being there’ – we learn what it is like to be a victim, a social actor, a survivor. We also learn, mainly via the video makers, what it is like to be an activist, a facilitator, an advocate, like Plaatje. Videos can be empowering – for their subjects, their communities and their producers. The STEPS For the Future series on AIDS videos for example, are gut-wrenching and disturbing visual sociologies of the ordinary. As sociologies, experiential, personal, visual, they are also explanatory, theoretical, methodological, and are compelling studies in and of themselves. They are innovative both in terms of form and practice, taking intertextuality to new heights. The ‘actors’ are sometimes the HIV/AIDS educational facilitators, and are recognised as such by audiences to whom they are screening their films.

Infrastructural developments

Part of the revitalisation of South African cinema since the late 1990s was the establishment of the National Film and Video Foundation in 1998. This body arose out of an industry-wide consultative process, which brought all sectors of the film and video industry into productive if often tense discussions over the post-apartheid structure of the film and video industries (cf. Tomaselli and Shepperson 2000; Botha 2003). The Foundation, administered by the Department of Arts and Culture, Science and Technology, allocates development grants for training, production and audience development purposes. The Foundation is responsible to a board of governors drawn from the film and video industry and civil society. This initiative encourages state and private financing partnerships with regard to production projects.

In South Africa, unlike in other African countries where broadcasting is part of the civil service, the film and television industries have always been closely integrated. This relationship therefore provides a much greater set of financing and market opportunities to South African filmmakers than is available in the rest of Africa. The impact of television, therefore, also needs to be assessed in relation to the development of South African cinema in a companion study.

Taking advantage of the relatively economic production cost structures of television, the public-service South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), the commercial subscription broadcaster M-Net, and the commercial free-to-air channel, e-TV, all encourage, develop and market the work of South Africa’s fiction filmmakers and documentary and short film producers. All three companies invest directly in production of feature films, and all kinds of innovative projects emerged in the 1990s from within the film and television industries as a whole. With Jeremy Nathan’s Africa Dreaming project of 1997, and his subsequent DV8 projects, the SABC combined with commercial entertainment giant Primedia, the Film Resource Unit, and other sponsors to produce a series of short features for broadcast. The SABC project placed South African filmmakers within the broader context of African cinema’s rich history. Thus, the first batch of films under the Africa Dreaming rubric all dealt with the theme of love, and combined female South African director Palesa ka Letlaka-Nkosi’s Mamalambo, with Namibian Richard Pakleppa’s The Homecoming, Mozambican Joao Ribeiro’s The Gaze of the Stars, The Last Picture from Zimbabwean Farai Sevenzo, The White and the Black by Senegalese Joseph Gai Ramaka and So Be It by Abderrahmane Sissako, from Tunisia.

M-Net, a South African-based multinational pay television corporation, initiated an annual New Directions competition for directors and scriptwriters in the early 1990s. In the first half of each calendar year, the company solicits proposals from first-time directors and writers. Proposals are scrutinised by a panel of experienced professionals, which included Lionel Ngakane, and through a process of mentored refinement six proposals are selected for production. The final products emerge from a further refinement session, in the form of thirty-minute dramas broadcast on selected M-Net channels. One project was later remade into a cinema feature, Chikin Biznis. The script was written by Mtutuzeli Matshoba, produced by Richard Green of New Directions, and directed by Ntshaveni Wa Luruli. The plot revolves around Sipho (Fats Bookholane), a retired office worker, who sells live chickens on the street in Soweto. He gets up to all kinds of tricks and crosses swords with everyone in his path. Chikin Biznis is not a political film. The freedom of the transition to democracy offered filmmakers an opportunity to make films about ordinary people engaged in everyday ordinary activities.

Another M-Net initiative was its annual All Africa Film Awards, an event first held in October 1995, following its earlier Awards, which only considered South African fare. Films from everywhere but South Africa were nominated in every category for the 1995 awards. The following year, the Cape Town ceremony saw one partial South African production, Jump the Gun, funded by Britain’s Channel 4 and directed by an Englishman, Les Blair, receive awards for best leading actor (Lionel Newton) best sound (Simon Rice), and best English language film. In 1997, an Egyptian film, Destiny (1997), piped the South African-made Paljas. The Awards showcased a range of producers, directors and products (even if only once a year) and brought the diversity of African cinema home to an audience which mostly watched sport and anything M-Net contracts from a variety of Hollywood sources. The Awards were discontinued in 2000.

Yesterday / tomorrow

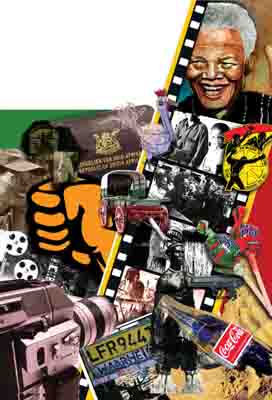

The technical golden age of South African cinema epics occurred between 1916 and 1922. The period of sheer quantity at thirty films a year occurred between 1962 and 1980, the heyday of apartheid. However, the South African industry’s political and aesthetic coming of age was signalled by a sustained movement towards historical interrogation that began in 1986. The mid-1990s saw the next phase facilitated by the new democratically elected government, which for the first time created a development strategy for the wider development of the industry as a whole, from grassroots video to international co-production. The new millennium has already seen the production of top quality local films and promises to be an exciting time for South African cinema. The local film industry is growing, owing to the regular filming of foreign productions in Cape Town and Durban where production costs are comparatively low. In April 2004 the government’s Department of Trade and Industry announced plans to provide financial incentives to increase foreign investment, to encourage the production of local content and boost job creation. In 2004, ten years after the country’s first democratic election, South African audiences were able to see the first full-length Zulu feature film with English subtitles. The film Yesterday tells the story of a mother who confronts her recently diagnosed HIV status in rural KwaZulu-Natal. The aptly-titled Forgiveness (2004), gives a compelling fictional account of an ex-policeman, granted amnesty at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), who approaches the family of the man he murdered in the name of apartheid for their forgiveness. The film highlights the moral issues raised in post-apartheid South Africa.

As someone privileged to have consulted for the government on its post-apartheid cinema and video development strategy, I see the fruition of my life’s work in these infrastructural developments, in that film and video are being developed as growth sectors within the broader economy, but in ways that are democratically inclusive rather than racially and sectorially exclusive. Within just a few years the fruits were clear to see: aesthetically, in terms of themes, and in terms of the infusion of refreshing new talent into both the television and cinema sectors. The role of new film schools and university courses, of course, played a key role in such developments.

However, as Jeanne Prinsloo argued in 1996, filmmaking in post-apartheid South Africa faces particular context-specific challenges. Following the demise of apartheid there was a renewed understanding of nationhood as a potentially unifying force in South African society. In this ‘renarration of nations’ (1996: 34), the discourse of the anti-apartheid struggle is frequently invoked in attempts to constitute ‘the rainbow nation’. However, this reconciliation discourse often ‘speaks to a condition as not yet achieved’ (ibid.: 47). In reality, apartheid has left its mark on the South African film industry. Therefore, Third Cinema aspirations need to be viewed against the infrastructural and institutional challenges that exist, such as unequal economic power relations, inadequate non-urban amd black township distribution networks and competition from cheaper (American) entertainment options (Prinsloo 1996). Prinsloo contends that at the discursive level, there is a need to balance celebratory reconciliation discourses with more critical engagements with the process of transformation, while at the same time resisting the pressure to always be politically correct. South African films need to draw on a range of narratives and a plurality of meanings.

——

Keyan G. Tomaselli – Encountering Modernity – Twentieth Century South African Cinemas

SAVUSA SERIES

Rozenberg Publishers Edition – ISBN 978 90 5170 886 8

Unisa Press Edition 978 1 86888449 0

A book describing the history of South African cinemas can never be about cinemas only, for the subject will always be intimately intertwined with its context, in this case 20th century South Africa.

Keyan Tomaselli, one of the founders of cultural studies in SA, explores in this book how South African cinemas and films have been decidedly shaped by the country’s history. In turn, films have inspired their makers and audiences to understand, and come to terms with, the complex phenomenon of modernity.

Discussing film theory, narratives, audiences and key South African films and filmmakers, Tomaselli aptly demonstrates that the time has come to adapt a more ‘African’ view on African cinemas, since western theories and models cannot automatically be applied to an African context.

Far from shying away from the personal, Tomaselli gives a conscientious and telling account of how his own experiences as a film maker, a cultural studies scholar, and a South African, have inevitably influenced his academic viewpoints and analysis.

About the author:

Prof. Keyan Tomaselli (Culture, Communication and Media Studies Department, University of KwaZulu-Natal) previously worked in the film industry and was co-writer of the White Paper on Film. His seminal books include The Cinema of Apartheid and Appropriating Images (1996). His interest are political economy, African cinema and visual anthropology.