Lejone John Ntema – Self-Help Housing In South Africa: Paradigms, Policy And Practice

Although the role of the state in housing provision in developing countries has varied considerably since World War II, Harris (1998; 2003) asserts that the state has, in general, continued to play a significant role in the provision of low-income housing. In turn, the role of the state – as embodied in its various policies, paradigms and practices – has become the subject of debate among academics, scholars, researchers and policy makers. Despite the fact that self-help housing is as old as humankind itself (Pugh, 2001), and that it was practised in different parts of the world before World War II (Harms, 1992; Harris, 2003; Parnell & Hart, 1999; Ward, 1982), it has since received varied institutional backing (Harris, 2003) and even more prominently since the early 1970s because of the World Bank’s influence in this regard (Pugh, 1992). From literature it is evident that one can distinguish between three different forms of self-help, namely laissez-faire self-help (virtually without any state involvement),

state aided self-help (site-and-services schemes) and institutionalised self-help (cases where the state actively supports self-help through housing institutions) (more detailed definitions follow in Section 1.1.2). Various forms of self-help housing have long been one of the most prevalent housing options in the world since World War II (see for example Dingle, 1999; Harris, 1998; Ward, 1982). The theoretical notion of self-help in the context of developing countries is commonly attributed to JFC Turner (Turner, 1976). Yet, it should be admitted that aided self-help in particular was both lobbied for, and practised, long before the rise of Turner’s ideas in the 1960s and 1970s (see Harris, 1998; 1999b). Furthermore, Turner’s

work, along with its practical consequences, is closely associated with the site-and-services and neo-liberal policies promoted by the World Bank (Pugh, 1992).

PhD-thesis University of the Free State, Bloemfontein: http://etd.uovs.ac.za/NtemaLJ.pdf

Blaise Dobson & Jean-Pierre Roux – Opportunities in Urban Informality, Development And Climate Resilience In African Cities

cdkn.org. Blaise Dobson and Jean-Pierre Roux (SouthSouthNorth) argue that African urbanisation and burgeoning informal settlements present an opportunity to build truly adaptive cities.

African cities are characterised by high levels of slums and informal settlements, largely informal economies, high levels of unemployment, majority youthful populations, and low levels of industrialisation. They have the highest growth rates in the world despite the fact that sub-Saharan Africa is still only approximately 40% urbanised. The urban poor, who largely reside in informal settlements and slums, are vulnerable to a range of global change effects, including global economic and climate change impacts. These can combine to have devastating effects on the poor, who generally survive on less than US$ 2 per day, but also on the ‘floating middle class’, who are defined as living on between US$ 2 – 4 per day, and constitute 60% of the African middle class.

The African Centre for Cities (ACC) and Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) hosted a three-day workshop in Cape Town in July aimed at developing a framework for understanding the intersection between climate resilience and urban informality, and promoting integrated urban development and management within African cities. ‘Champion groups’ from Accra (Ghana), Kampala (Uganda) and Addis Ababa (Ethiopia), which included local authorities, academia and civil society attended.

http://cdkn.org/opportunities-african-cities/

Natalia Ojewska – Ghana’s Old Fadama Slum: “We Want to Live in Dignity”

thinkafricapress.com. August 7, 2013. “On the outskirts of Accra, alongside the Odaw River and the Korle Lagoon, lies the slum of Old Fadama. Pejoratively referred to by many Ghanaians as a modern day “Sodom and Gomorrah”, Old Fadama is said to be home to around people, making it Ghana’s biggest slum.

Life here can be precarious and opportunities for social mobility are few and far between. Made up of a bustling, roughshod tessellation of closely built wooden structures, up to twenty people sleep on the floors of its individual ‘kiosks’ – each one an average of 3-4m2. Social amenities such as sanitation, running water, medical care and waste collection are hard to come by.

Read more: http://www.thinkafricapress.com/old-fadama-slum

Moladi – Imagination For People – Social Innovation For The Bottom Of The Pyramid

designmind. August 2013. About the project

designmind. August 2013. About the project

The aim of empowering people at the Bottom of the Pyramid is to identify appropriate technical solutions in order to tackle basic needs in developing countries. But what are basic needs exactly?

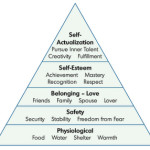

In 1943, Abraham Maslow presented his well-known “hierarchy of needs”. According to his theory, people need food, water, sleep and warmth the most. These are considered to be basic needs and it is only when these basic physical requirements are met that individuals can progress to the next level, that of safety and security. Once these needs are fulfilled, interpersonal needs such as love and friendship, as well as the need for self-esteem and respect from others, can gain importance. Self-fulfilment and the realization of one’s own potential represent the top of the hierarchy.

What does Maslow tell us? Food, sanitation and shelter are not only mandatory preconditions for survival – they also lay the foundations for the personal development of an individual. People can only grow and develop if they don’t suffer from basic supply problems: Children in school simply cannot learn on an empty stomach and the social and economic development of communities depends on access to safe water and sanitation services.

Today, the basic needs approach has become an integral part of theories about human motivation, social and economic development, particularly in the context of development in low income countries. It has become one of the major approaches to the measurement of what is believed to be an eradicable level of poverty and it also forms the center of people-focused development strategies. The “basic needs strategy in development planning” by the ILO (1976), for instance, calls for giving priority to meeting minimum human needs, providing certain essential public services, and also stresses the importance of citizen participation in the determination and tackling of needs. Citizen participation, economic growth, globalization and technology are all intertwined in these development approaches.

The definition of basic needs within the framework of empowering people therefore also encompasses food, water, shelter (moladi), sanitation, education and healthcare. The use of technology in concert with social entrepreneurship to improve the quality of life and social structures.

Read more: http://www.designmind.co.za/for-the-bottom-of-the-pyramid

Leon Kaye – Social Enterprise In Indian Slums

theguardian.com. August, 5, 2013. Slums in India have grabbed the attention of activists, journalists and humanitarians for decades. And as urbanisation in India surges, living conditions in these poor areas within megacities have become increasingly dire. New slums have emerged on the outer rings of older ones, resulting in situations like the one in Mumbai’s Dharavi where its one million people now sit on what many Indian leaders regard as prime real estate.

Having spent time in some of the slums of Mumbai and Delhi earlier this year, I found it was easy to focus on the jarring first impressions: the overcrowding, filth and poverty. But peel back the harsh veneer and one sees the budding social enterprises that thrive in Mumbai’s M Ward and Delhi’s Holumbi Khurd. New business models from large and small firms alike that foster jobs, conserve resources and inspire innovation thrive within these neighbourhoods. The scarcity of resources like water and energy force residents to become creative, thrifty and share with their neighbours.

Read more:http://www.theguardian.com/social-enterprise-india-slums?

Kim Verbrugghe – The Rise Of Our Shadow Cities – Innovation In The Slums

chrysalis.deepend.com. August 2, 2013. In Mesopotamia, the Nile would go out of its boundaries and kilometres of land would be swiped away with water. There were long periods of draught and the water of the Nile would leave fertile sediment on the fields. About 1800 BCE, the Egyptians used a natural lake as a reservoir during dry periods. They also invented ‘flood irrigation’ and used the flooding of the Nile to distribute the water via channels across fields.

I recently listened to a TED talk about the future of our cities. Scientists believe that our future cities won’t be the metropoles we have today but the micro communities that have established themselves over the course of the years. We see these translated in similar ways across the world. The slums in India. Favelas in South America.

Cities present the best hope for a sustainable future. Family size and carbon footprint fall as density rises. You can see this best in the areas where urbanisation happens most rapidly: the slums. The working slums help create prosperity. They are valuable as a group.

Read more: http://chrysalis.deepend.com.au/the-rise-of-our-shadow-cities-innovation