Is Another World Really Possible? The Slogans Of The French Revolution Reconsidered

The famous slogan of the French Revolution was “liberty, equality, fraternity“. In the succeeding two centuries the world has demonstrated both the contradictions of this slogan and the very limited degree to which in fact any of its three elements have been realized anywhere in the modern world-system.

The famous slogan of the French Revolution was “liberty, equality, fraternity“. In the succeeding two centuries the world has demonstrated both the contradictions of this slogan and the very limited degree to which in fact any of its three elements have been realized anywhere in the modern world-system.

Today, the question is whether, in a future world-system, there are ways of making this trio more compatible each with the other. We are dealing here not with this trinity but rather with the relation between inequality, pluralism, and the environment. It is hard to say what the French revolutionaries would make of this discussion. Pluralism was exactly the opposite of their aspirations, since they wished to eliminate all intermediaries between the individual and the state of all the citizens. The environment was entirely outside their topic. And inequality was assumed to be inevitable on tis way out, precisely because of their victorious revolution.

“But these questions about both trinities are very much unresolved today. The next several decades will be a period of collective world decision about precisely these issues, about whether another world is really possible in a foreseeable future. I shall start by discussing the least discussed, indeed the long almost-forgotten, member of the French Revolution’s trinity, fraternity. It is only in recent decades that fraternity has returned to the forefront of our collective concerns, but it has indeed returned, and with a vengeance”.

Read more

Why Do So Few Christian Syrian Refugees Register With The United Nations High Commissioner For Refugees?

The Syrian refugee crisis is one of the worst humanitarian disasters since World War II. It is estimated that more than 11 million Syrians have been forced to flee their homes since the outbreak of the civil war in 2011. More than six million are internally displaced, while approximately 4.6 million have taken refuge in Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, and Egypt, and another one million have sought refuge in Europe. Against that background, it is striking that the United States has accepted only 10,000 Syrian refugees. In contrast, Canada, with a population barely one-tenth the size of that of the United States, has accepted three times more Syrian refugees.

There is considerable interest and concern in the United States as to why so few Syrian Christians are registered as refugees by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and why so few Syrian Christian refugees eventually resettle in the United States.

While religion should not be an issue when it comes to the treatment of refugees, the numbers need to be analyzed to determine what they really mean and how they can be explained. Although Christians are generally represented to be as much 10 percent of Syria’s prewar population, the total percentage of Syrian Christian refugees who registered with the UNHCR is only 1.2 percent [i].

Recent news reports state that only 56 of the 10,000 Syrians refugees who resettled in the United States in 2016 are Christian.[ii] These numbers have led to criticism that the systems in place discriminate against Christians, making it difficult for them to register.

This report, which relies mostly on information gleaned from interviews conducted with people and organizations in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan in June and July 2016, provides contextual explanations of why Syrian Christians are not registering as refugees with the UNHCR.

This report also contains the findings of interviews conducted in the United States with individuals associated with U.S.-based organizations and Syrian religious and activist groups. The broader topic of discrimination and the horrors of the Syrian civil war, including its effects on the Syrian Christian community, should be examined more fully, but are not covered by this report. It should be noted that much of the report contains anecdotal information. Very few organizations or individuals—especially individual refugees—were willing to be quoted on the record, but informal conversations with a number of organizations and individuals made this report possible.

One notable finding is that there are sharply different perceptions in the United States, on one hand, and in Lebanon and Jordan, on the other, about treatment of Syrian Christian refugees: U.S. suppositions of anti-Christian discrimination and systemic difficulties as the possible reasons for the small numbers of this group being registered and resettled as refugees contrasts with the perception, especially in Lebanon and Jordan, that Syrian Christians receive preferential treatment and are resettled at a higher rate than other refugees.

Syria has always been a diverse state with numerous minority and religious groups. The Kurds (in the northeast portion of the country) are the largest national minority group. Next are the Palestinians, who fled to Syria following the 1948 and 1967 Arab-Israeli wars, mostly living in refugee camps administered by the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). Armenians are also a prominent religious and national minority group, living primarily in Aleppo and estimated to number from 70,000 to 100,000 at the beginning of the current civil war. There are also smaller numbers of Turkmen and Yazidis. Most Syrians are Sunni Muslims, but other Muslim sects include Alawites, Shiites, and Druze.

Christian minority groups are estimated to represent seven to 10 percent of the pre-conflict population. Included are Greek Orthodox, Melkite Catholics, Syriac Orthodox, Maronites, and other smaller sects. Most of the Christians are Orthodox, with the largest group centered on the Orthodox Church of Antioch and the Eastern Catholic (or Melkite) Church. Other Christian sects include Armenians, Syriac Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, other Orthodox churches, and a small Protestant community.

The Syrian civil conflict and outflow of refugees

The Syrian civil conflict that began in March 2011 has become one of the greatest human tragedies since World War II. Upward of 400,000 people have been killed, and over five million have been displaced and sought refuge outside of Syria. This does not include millions of Syrians who are internally displaced. The refugee crisis has had substantial impact not only on neighboring countries, but also on the world in general. Most of those displaced have sought refuge in Turkey (upward of two million), Jordan (1.5 million to two million), and Lebanon (one million to 1.5 million). Although Turkey and Jordan have created refugee camps, most refugees—perhaps as many as 85 percent—do not stay in the camps, preferring to reside in urban areas (see Appendix 1). Turkey’s government runs the camps in its country, while the UNHCR administers those in Jordan. Lebanon, which still hosts a significant number of Palestinian refugee camps from the 1948 and 1967 wars, has decided not to create any new official camps. This has the unintended consequence of generating more than the one million refugees, who have subsequently dispersed and settled in communities throughout the country.

Read more

Research Dossier Leiden University: ‘Africa Reconsidered’

Africa is a continent in transition, with developments occurring at breakneck speed. African Studies scholars from different academic disciplines of Leiden University have conducted research for many decades. Their close links with African partners and their emphasis on fundamental research have enabled them to generate insights that benefit both African and Western societies. Leiden University created a new research dossier ‘Africa reconsidered’ on its website, for which many ASCL researchers were interviewed.

Africa is a continent in transition, with developments occurring at breakneck speed. African Studies scholars from different academic disciplines of Leiden University have conducted research for many decades. Their close links with African partners and their emphasis on fundamental research have enabled them to generate insights that benefit both African and Western societies. Leiden University created a new research dossier ‘Africa reconsidered’ on its website, for which many ASCL researchers were interviewed.

Read the new research dossier ‘Africa reconsidered‘ in English.

Lees het wetenschapsdossier ‘Afrika heroverwogen‘ in het Nederlands.

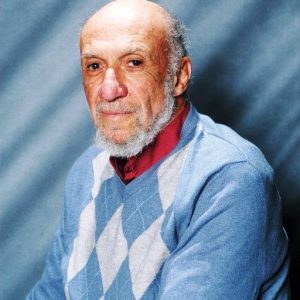

“Trump Feels A Kinship With Authoritarian Leaders”: Richard Falk On Turmoil In The Middle East

Since Trump’s visit to the Middle East, the region is experiencing new forms of turmoil, with the boycott against Qatar by several Gulf countries and Egypt reflecting the manifestation of geopolitical rivalries encouraged by Trump’s support for dictatorial regimes in the region willing to join the US in the fight against terrorism. For the latest developments in the Middle East, Truthout spoke with Richard Falk, emeritus professor of international relations at Princeton University, who is now in the region for a series of public lectures.

C.J. Polychroniou: Richard, you are traveling and lecturing at the moment in the Middle East. How are the media in countries like Lebanon, Israel and Turkey treating Trump’s policies in the region, and what’s your reading of the mood on the ground among common folk?

Richard Falk: I have just arrived in Istanbul after spending several days in Beirut. While in Lebanon, in addition to giving a public lecture at the end of a cultural festival on the theme, “The rise of populism, Trumpism, and the decline of US leadership,” I had the opportunity to interact with a wide range of people. As far as Trump is concerned, there was virtual unanimity that he is worsening an already volatile situation in the region. His trip to Riyadh was viewed in Beirut as a stunning display of incompetence and bravado, topped off by succumbing to a Saudi/Israeli regional agenda focused on building a menacing anti-Iran coalition and misleading publicity surrounding a nominal commitment to join forces to combat ISIS (also known as Daesh). Trump was viewed as a leader who did not understand the region and was more interested in pushing destabilizing arms sales than in genuinely promoting stability and conflict resolution.

Why is Qatar singled out on terror when it is a well-known fact that Saudi Arabia has been a chief supporter of the most radical ideological version of Islam, and Turkey’s President Erdogan has been accused of aiding ISIS and other extremists against Kurds and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad?

The short answer is geopolitics. Saudi Arabia, like Israel, has a “special relationship” with the United States, meaning that in diplomatic practice, Washington adopts a subservient posture that includes seeing the world through a distorted optic provided by the Saudi monarchy. Trump did not initiate this American tendency to avert its eyes when it comes to the massive evidence of Saudi support for Islamic extremism, but he seems to be carrying further this form of geopolitical [ignorance].

When it comes to Turkey, the American attitude is ambivalent, regarding Turkey as a sufficiently important strategic partner via NATO, as well as the site of the important American Incirlik Air Base to justify looking the other way when it comes to indications of earlier Turkish support for ISIS in the context of implementing its anti-Assad Syrian policies. Of course, there is evidence of contradictions along similar lines with respect to pre-Trump US policies in Syria. All hands are dirty with regard to Syria. The Syrian people are continuing to pay a huge price for this mixture of internal struggle and a multilevel proxy war engaging regional and global actors.

Singling out Qatar is the strongest instance of the Saudi regional game. Saudi Arabia has long been bothered by the relative independence of Qatar in relation to a series of issues that have nothing to do with terrorism. These include the creation of Al Jazeera, a show of sympathy for the Arab Spring movements of 2011, asylum for the Muslim Brotherhood leadership after the Sisi coup of 2013, hosting Hamas leaders and tangible support for the Palestinian struggle — including aid to Gaza, and relatively friendly relations with Iran partly as a result of sharing a huge natural gas field.

Read more

Myths Of Globalization: Noam Chomsky And Ha-Joon Chang In Conversation

Since the late 1970s, the world’s economy and dominant nations have been marching to the tune of (neoliberal) globalization, whose impact and effects on average people’s livelihood and communities everywhere are generating great popular discontent, accompanied by a rising wave of nationalist and anti-elitist sentiments. But what exactly is driving globalization? And who really benefits from globalization? Are globalization and capitalism interwoven? How do we deal with the growing levels of inequality and massive economic insecurity? Should progressives and radicals rally behind the call for the introduction of a universal basic income? In the unique and exclusive interview below, two leading minds of our time, linguist and public intellectual Noam Chomsky and Cambridge University economist Ha-Joon Chang, share their views on these essential questions.

C. J. Polychroniou: Globalization is usually referred to as a process of interaction and integration among the economies and people of the world through international trade and foreign investment with the aid of information technology. Is globalization then simply a neutral, inevitable process of economic, social and technological interlinkages, or something of a more political nature in which state action produces global transformations (state-led globalization)?

Ha-Joon Chang: The biggest myth about globalization is that it is a process driven by technological progress. This has allowed the defenders of globalization to brand the critics as “modern Luddites” who are trying to turn back the clock against the relentless progress of science and technology.

However, if technology is what determines the degree of globalization, how can you explain that the world was far more globalized in the late 19th and the early 20th century than in the mid-20th century? During the first Liberal era, roughly between 1870 and 1914, we relied upon steamships and wired telegraphy, but the world economy was on almost all accounts more globalized than during the far less liberal period in the mid-20th century (roughly between 1945 and 1973), when we had all the technologies of transportation and communications that we have today, except for the internet and cellular phones, albeit in less efficient forms.

The reason why the world was much less globalized in the latter period is that, during the period, most countries imposed rather significant restrictions on the movements of goods, services, capital and people, and liberalized them only gradually. What is notable is that, despite [its] lower degree of globalization … this period is when capitalism has done the best: the fastest growth, the lowest degree of inequality, the highest degree of financial stability, and — in the case of the advanced capitalist economies — the lowest level of unemployment in the 250-year history of capitalism. This is why the period is often called “the Golden Age of Capitalism.”

Technology only sets the outer boundary of globalization — it was impossible for the world to reach a high degree of globalization with only sail ships. It is economic policy (or politics, if you like) that determines exactly how much globalization is achieved in what areas.

The current form of market-oriented and corporate-driven globalization is not the only — not to speak of being the best — possible form of globalization. A more equitable, more dynamic and more sustainable form of globalization is possible.

We know that globalization properly began in the 15th century, and that there have been different stages of globalization since, with each stage reflecting the underlying impact of imperial state power and of the transformations that were taking place in institutional forms, such as firms and the emergence of new technologies and communications. What distinguishes the current stage of globalization (1973-present) from previous ones?

Chang: The current stage of globalization is different from the previous ones in two important ways.

The first difference is that there is less open imperialism.

Before 1945, the advanced capitalist countries practised [overt] imperialism. They colonized weaker countries or imposed “unequal treaties” on them, which made them virtual colonies — for example, they occupied parts of territories through “leasing,” deprived them of the right to set tariffs, etc.

Since 1945, we have seen the emergence of a global system that rejects such naked imperialism. There has been a continuous process of de-colonialization and, once you get sovereignty, you became a member of the United Nations, which is based upon the principle of one-country-one-vote.

Read more

Challenges For Education In An International Setting

Third Level Education is in many respects increasingly changing in the light of two general developments: internationalisation and globalisation on the one hand, marketisation and commodification on the other hand. Whereas the first is apparently taking up on an intrinsic value of education (‘universality of knowledge’), the second can be seen as opposing its values (‘knowledge cannot be bought and sold as any other good’). However, the discussion of this contribution shows that in reality we find that on the side of implementation big business has a standing that finds its way much easier to the stage of implementation.

Third Level Education is in many respects increasingly changing in the light of two general developments: internationalisation and globalisation on the one hand, marketisation and commodification on the other hand. Whereas the first is apparently taking up on an intrinsic value of education (‘universality of knowledge’), the second can be seen as opposing its values (‘knowledge cannot be bought and sold as any other good’). However, the discussion of this contribution shows that in reality we find that on the side of implementation big business has a standing that finds its way much easier to the stage of implementation.

Keywords: third level education, globalisation, internationalisation, marketisation, educational values, legitimation.

This article goes back to the work of the authors in Connection with a Presentation to Conference in Shanghai, October 2016. The conference theme was about higher education in an international setting in which presentation included a wide range of progresses made and challenges met within the joint-venture programmes between western universities and their Chinese counterparts.

See: https://youtu.be/6FJxTwHuotI

Third Level Education is increasingly concerned with distinct, though mutually influencing aspects – they can be aligned along two dimensions: the first spans between development of personality and defining ones’ place in professional terms; the other is about growing up in a new global scientific community. What had been for centuries a very privileged area for a few outstanding and lucky scholars, is becoming a field that is increasingly open for many, ready to engage at different levels, beginning with the bachelors degrees. Let us take Bangor College China as an example.

Bangor College China is a joint venture between Bangor University in the UK and the Central University of Forestry and Technology (CSUFT) in China. It was established with the approval of the Chinese Education Ministry in 2014 as an advanced model to facilitate the internationalization of Chinese higher education. A dedicated Bangor College China offers full degrees in China which is the first for a British university. It offers four programmes including BSc in Banking and Finance; BSc in Accounting and Finance; BSc in Electronic Engineering; and BSc in Forestry and Environment Management with more than 600 students in their first and second year studies. A team of dedicated and experienced staff of teaching and administration from both Bangor University and CSUFT were in interaction. Over the last two years Bangor University has invested heavily on Bangor College China. It is responsible for the quality of the programmes and ensures that the teaching standards, assessments and student experience are equivalent to those at the Bangor home campus.

– Although the running of the joint school in general goes smoothly with good intention from both universities in the UK and China, some major challenges lie ahead in the areas of the merger of different administrative cultures; the search for professional standards; the work towards a common professional understanding, making reference to wealth of different traditions; and the development of new ways learning.

– Remarkable new opportunities go hand in hand with grave challenges: as much as we find the strive for excellence as major field of competitive concern, at the very same time we find the incredible opportunities for smaller projects, such as Bangor College China, is an example that locates the challenge of development of personality and defining ones’ place in professional terms in the context of a collaborative setting globally.

Defining the Field

International education – as matter of ranking and also cooperation and as matter of the excitement to explore new shores – experiences a kind of hype, easily overlooking the inherent contradiction. But can we really speak of an inherent contradiction? If we take things at the level of appearance, we find, of course, – and very valid – the feature of cutthroat competition – the winner gets all, at least the cherries of qualified staff and students and also the relevant resources.[i]

Although this is undeniably a strong force, we can take as well a more optimistic view – optimistic for those that are not in any relevant top-league, and – importantly – who are actually not seriously striving to gain entrance. Though it is often said that we do stand on the shoulders of giants, we also – and increasingly – are part of an overall team game – not least looking at the ancient Western cultures, claimed to be the crèche of today’s enlightened cultures in the east and west, we know that the understanding was very much one of discourse – a discourse between ‘experts’ and between ‘experts’ and ‘pupils’. The term ‘scholar’, referring to the learned person and the student alike, may give a hint, as does the term ‘scientific community’ – and it is worthwhile to mention in parenthesis that these terms are paradoxically loosing meaning at a time when scientific work can only be imagined as part of an undertaking that is social in terms of time and content – without denying the greatness, for instance of Isaac Newton. It did not require much more than a well-studied individual mind and the observation of an apple falling from the tree to find out about the law of gravity. However, using this law as crucial basic knowledge to the undertaking of flying to the moon or exploring other planets, requires the genius of many people collaborating, as also the academic labour is divided and a huge amount of resources. And let us be honest, and a bit German, by referring to the poet Goethe who states in his masterpiece:

Two souls alas! are dwelling in my breast;

And each is fain to leave its brother.

The one, fast clinging, to the world adheres

With clutching organs, in love’s sturdy lust;

The other strongly lifts itself from dust

To yonder high, ancestral spheres

(von Goethe 1808).

Read more