Generations And The Future Of Distance Workers

A distance worker performs his work at the ‘production position’. The results of his work emerge at the ‘outcome position’, at a distance from the production position. An example is a series of guest lectures I presented at the University of Johannesburg. I lectured in Utrecht in a video conference center. The students were located in South Africa. After a few minutes, I forgot that I was speaking to a glass screen. I could see and hear the students’ reactions to my presentation. The male students participated a bit more actively than their female colleagues. To support my lectures, I had distributed a set of handouts in advance.

In this essay, I will first discuss the dynamics of the Pattern of Generations. These dynamics will structure the future of distance workers substantially. I will base this discussion on my research program on generations, active since 1983. Secondly, I will present several examples of distance activities. Thirdly, the future of distance workers will be discussed in detail.

The Pattern of Generations and its Dynamics

The concept of generations has been a part of our cultural heritage for many centuries. We can define a generation as: ‘the clustering of a set of birth cohorts as an effect of one or more major events in society’. [1] The impact of major events is particularly strong during the formative period of the life course. The formative period is from around age twelve to twenty-three. In this period intelligence and memory capacity reach their highest level in the life course. [2]

In 2015, the pattern of generations can be represented by a number of idealizations. [3] The ‘Silent Generation’ is birth cohorts from 1930 to 1945. The ‘Early Babyboom Generation’ is cohorts born from 1945 to 1955. The ‘Late Babyboom Cohorts’ go from 1955 to 1980. The ‘Pragmatic Generation’, also called ‘Generation X, is situated between 1980 and 1990. ‘Generation Y’ goes from 1990 to 2000’, and ‘Generation Z’ starts in 2000.

The dynamics of generations are represented by the changes over time that each generation experiences. Take the ‘Early Babyboom Generation’ for instance. In its formative period it experienced the emergence of ICT. In its formative period, ‘Generation Z’ will experience the impact of substantial improvements in ICT, combined with a substantial increase in command of the English language.

Generations can be discussed with the aid of idealizations. Another type of generation consists of the results of empirical research in sociology and related social sciences. Third, we are confronted with the images of generations in everyday life. [4]. Read more

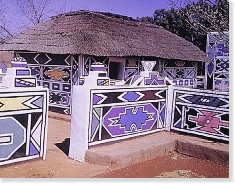

The Ndebele Nation

12-05-2015 ~ With an Introduction by Milton Keynes

The Ndebele of Zimbabwe, who today constitute about twenty percent of the population of the country, have a very rich and heroic history. It is partly this rich history that constitutes a resource that reinforces their memories and sense of a particularistic identity and distinctive nation within a predominantly Shona speaking country. It is also partly later developments ranging from the colonial violence of 1893-4 and 1896-7 (Imfazo 1 and Imfazo 2); Ndebele evictions from their land under the direction of the Rhodesian colonial settler state; recurring droughts in Matabeleland; ethnic forms taken by Zimbabwean nationalism; urban events happening around the city of Bulawayo; the state-orchestrated and ethnicised violence of the 1980s targeting the Ndebele community, which became known as Gukurahundi; and other factors like perceptions and realities of frustrated economic development in Matabeleland together with ever-present threats of repetition of Gukurahundi-style violence—that have contributed to the shaping and re-shaping of Ndebele identity within Zimbabwe.

The Ndebele history is traced from the Ndwandwe of Zwide and the Zulu of Shaka. The story of how the Ndebele ended up in Zimbabwe is explained in terms of the impact of the Mfecane—a nineteenth century revolution marked by the collapse of the earlier political formations of Mthethwa, Ndwandwe, and Ngwane kingdoms replaced by new ones of the Zulu under Shaka, the Sotho under Moshweshwe, and others built out of Mfecane refugees and asylum seekers. The revolution was also characterized by violence and migration that saw some Nguni and Sotho communities burst asunder and fragmenting into fleeing groups such as the Ndebele under Mzilikazi Khumalo, the Kololo under Sebetwane, the Shangaans under Soshangane, the Ngoni under Zwangendaba, and the Swazi under Queen Nyamazana. Out of these migrations emerged new political formations like the Ndebele state, that eventually inscribed itself by a combination of coercion and persuasion in the southwestern part of the Zimbabwean plateau in 1839-1840. The migration and eventual settlement of the Ndebele in Zimbabwe is also part of the historical drama that became intertwined with another dramatic event of the migration of the Boers from Cape Colony into the interior in what is generally referred to as the Great Trek, that began in 1835. It was military clashes with the Boers that forced Mzilikazi and his followers to migrate across the Limpopo River into Zimbabwe.

As a result of the Ndebele community’s dramatic history of nation construction, their association with such groups as the Zulu of South Africa renowned for their military prowess, their heroic migration across the Limpopo, their foundation of a nation out of Nguni, Sotho, Tswana, Kalanga, Rozvi and ‘Shona’ groups, and their practice of raiding that they attracted enormous interest from early white travellers, missionaries and early anthropologists. This interest in the life and history of the Ndebele produced different representations, ranging from the Ndebele as an indomitable ‘martial tribe’ ranking alongside the Zulu, Maasai and Kikuyu, who also attracted the attention of early white literary observers, as ‘warriors’ and militaristic groups. This resulted in a combination of exoticisation and demonization that culminated in the Ndebele earning many labels such as ‘bloodthirsty destroyers’ and ‘noble savages’ within Western colonial images of Africa.

Ndebele History

Ndebele History

With the passage of time, the Ndebele themselves played up to some of the earlier characterizations as they sought to build a particular identity within an environment in which they were surrounded by numerically superior ‘Shona’ communities. The warrior identity suited Ndebele hegemonic ideologies. Their Shona neighbours also contributed to the image of the Ndebele as the militaristic and aggressive ‘other’. Within this discourse, the Shona portrayed themselves as victims of Ndebele raiders who constantly went away with their livestock and women—disrupting their otherwise orderly and peaceful lives. A mythology thus permeates the whole spectrum of Ndebele history, fed by distortions and exaggerations of Ndebele military prowess, the nature of Ndebele governance institutions, and the general way of life.

My interest is primarily in unpacking and exploding the mythology within Ndebele historiography while at the same time making new sense of Ndebele hegemonic ideologies. My intention is to inform the broader debate on pre-colonial African systems of governance, the conduct of politics, social control, and conceptions of human security. Therefore, the book The Ndebele Nation (see: below) delves deeper into questions of how Ndebele power was constructed, how it was institutionalized and broadcast across people of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. These issues are examined across the pre-colonial times up to the mid-twentieth century, a time when power resided with the early Rhodesian colonial state. I touch lightly on the question of whether the violent transition from an Ndebele hegemony to a Rhodesia settler colonial hegemony was in reality a transition from one flawed and coercive regime to another. Broadly speaking this book is an intellectual enterprise in understanding political and social dynamics that made pre-colonial Ndebele states tick; in particular, how power and authority were broadcast and exercised, including the nature of state-society relations.

What emerges from the book is that while the pre-colonial Ndebele state began as an imposition on society of Khumalo and Zansi hegemony, the state simultaneously pursued peaceful and ideological ways of winning the consent of the governed. This became the impetus for the constant and ongoing drive for ‘democratization,’ so as contain and displace the destructive centripetal forces of rebellion and subversion. Within the Ndebele state, power was constructed around a small Khumalo clan ruling in alliance with some dominant Nguni (Zansi) houses over a heterogeneous nation on the Zimbabwean plateau. The key question is how this small Khumalo group in alliance with the Zansi managed to extend their power across a majority of people of non-Nguni stock. Earlier historians over-emphasized military coercion as though violence was ever enough as a pillar of nation-building. In this book I delve deeper into a historical interrogation of key dynamics of state formation and nation-building, hegemony construction and inscription, the style of governance, the creation of human rights spaces and openings, and human security provision, in search of those attributes that made the Ndebele state tick and made it survive until it was destroyed by the violent forces of Rhodesian settler colonialism.

The book takes a broad revisionist approach involving systematic revisiting of earlier scholarly works on the Ndebele experiences in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and critiquing them. A critical eye is cast on interpretation and making sense of key Ndebele political and social concepts and ideas that do not clearly emerge in existing literature. Throughout the book, the Ndebele historical experiences are consistently discussed in relation to a broad range of historiography and critical social theories of hegemony and human rights, and post-colonial discourses are used as tools of analysis.

Empirically and thematically, the book focuses on the complex historical processes involving the destruction of the autonomy of the decentralized Khumalo clans, their dispersal from their coastal homes in Nguniland, and the construction of Khumalo hegemony that happened in tandem with the formation of the Ndebele state in the midst of the Mfecane revolution. It further delves deeper into the examination of the expansion and maturing of the Ndebele State into a heterogeneous settled nation north of the Limpopo River. The colonial encounter with the Ndebele state dating back to the 1860s culminating in the imperialist violence of the 1890s and the subsequent colonization of the Ndebele in 1897 is also subjected to consistent analysis in this book.

What is evident is that the broad spectrum of Ndebele history was shot through with complex ambiguities and contradictions that have so far not been subjected to serious scholarly analysis. These ambiguities include tendencies and practices of domination versus resistance as the Ndebele rebelled against both pre-colonial African despots like Zwide and Shaka as well as against Rhodesian settler colonial conquest. The Ndebele fought to achieve domination, material security, political autonomy, cultural and political independence, social justice, human dignity, and tolerant governance even within their state in the face of a hegemonic Ndebele ruling elite that sought to maintain its political dominance and material privileges through a delicate combination of patronage, accountability, exploitation, and limited coercion.

The overarching analytical perspective is centred on the problem of the relation between coercion and consent during different phases of Ndebele history up to their encounter with colonialism. Major shifts from clan to state, migration to settlement, and single ethnic group to multi-ethnic society are systematically analyzed with the intention of revealing the concealed contradictions, conflict, tension, and social cleavages that permitted conquest, desertions, raiding, assimilation, domination, and exploitation, as well as social security, communalism, and tolerance. These ideologies, practices and values combined and co-existed uneasily, periodically and tendentiously within the Ndebele society. They were articulated in varied and changing idioms, languages and cultural traditions, and underpinned by complex institutions. Read more

Love Letters In A Networked Age

O, darling of mine, my God, how you make me happy! O, this letter, this letter from you, that I kiss and kiss…O, that you love me—that you love me too, and said so… O, bliss, o, bliss, that I am something in your life.

–Jeanne Reyneke van Stuwe to Willem Kloos, April 1899

I think I must have been the last person in the developed world still writing love letters. By 19th-century standards (see above), I don’t suppose they were very romantic. J. and I were children of a less gushy, more cynical age. We had already gone way beyond kissing each other’s letters, but felt we were being very daring—stepping over an invisible line of appropriate distance and refusal to hope—on the rare occasions when we wrote “I love you.”

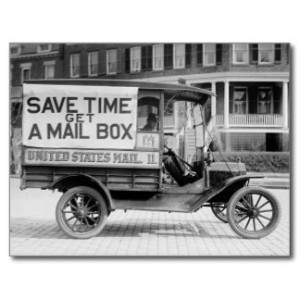

The point is, we wrote letters. Long ones, handwritten, with stamps. We kept track of last pickup times, ran downstairs when we heard the mail slot bang. We were patient: to send a letter and get its transatlantic answer took at least ten days. The phone, at a dollar a minute, was out of the question.

When one of J.’s letters came, I would carry it around with me for days. At quiet moments I would take it out, gaze at my own address written in his long-legged, beautiful hand, unfold the pages, and reread them. Sometimes J. sent me drawings or photos. Once he sent me flowers: he cut out, pasted onto paper, and mailed me the side of a milk carton with tulips on it. The day I lost one of J.’s illustrated postcards in the subway on my way home, I was as distraught as I would be now if my hard disk crashed.

If we had met now, and not 15 years ago, we wouldn’t be writing letters. We would be instant messaging, Skyping, taking out our iPhones to gaze at each other’s houses on Google Earth or Street View. We would e-mail links and photos, add each other’s local weather to our start page, friend each other on Facebook. We would exchange a lot of data.

We probably wouldn’t have missed letter-writing. Attachment to the letter as a physical object—isn’t that really just nostalgia? Writing letters is like listening to your old LPs: you like the way they look, you’re sentimental about their vinyl pop and scratch. But the music is the same.

Sometimes I wonder, though. J. and I are shy people. We felt safer on the page. In the digital world, would we still have gotten to know each other? Would it still have felt like a conversation?

The conversation on paper was, is, the magic of the letter. It’s why we write them, and it’s why we love to read other people’s. Later on, when I worked on a biography, I read folder after folder of my subject’s mail. Often it was like watching a passionate two-character play. The correspondents usually began as strangers and got to know each other over time. They gossiped, argued, made abrupt confessions, helped each other work out ideas, fell out, became friends.

A good letter-writer is a performer, playing a role for an audience of one. But performance can, paradoxically, lead to honesty, and distance enable greater frankness than a face-to-face talk. Belle van Zuylen, one of the all-time great literary flirts, wrote to Constant d’Hermenches in 1764, “I can’t speak to you the same way I can write to you. When I speak to you I see a man before me, a man with whom I have conversed no more than ten times in my life. It’s only natural that I should be thrown into confusion and not dare say certain words…”

We all know that feeling. Teenagers often have it; it’s one reason they would rather text each other than call. Could Belle van Zuylen still have flirted if she’d had a webcam? Would J. and I, through the static of Skype, still have told each other the truth about ourselves?

I miss the frankness of letters. But what I miss even more is the patience. Any letter, to anyone—I wrote a lot to friends in those days, too—took time. It had to be composed. You felt like you had to fill the paper down to the end; if you got to the bottom and weren’t quite done, you might continue along one side or add a note in the top margin. To achieve that feeling of a conversation, you had to think about what you wanted to say.

In his Atlantic article “Is Google Making Us Stupid?” technology journalist Nicholas Carr writes that since he started using the Internet, he has become so used to skipping from link to link that he has lost the knack of reading. “I get fidgety, lose the thread, begin looking for something else to do. I feel as if I’m always dragging my wayward brain back to the text.”

In the same way, I’ve lost the knack of letter-writing. I find myself skipping, not just from link to link, but from friend to friend. Many of my friendsare links, on a social networking site. I keep in touch with more people than ever, but superficially. Even e-mail often feels too time-consuming or too intimate. To write a long message is almost bad manners. It’s a breach of the most important rule of modern etiquette: don’t take up other people’s time.

Many people I know, including me, now communicate by posting notes for their entire social circle to read. The other day, I mentioned in an e-mail to a friend 3,000 miles away that a mutual acquaintance had had dinner at my house. He wrote back, “I know. I read it on her blog.”

Without the focus that the individual letter demands, we spread ourselves widely but thinly among our friends. If I miss the letter, it’s partly because I’m worried that, in the words of New York playwright Richard Foreman, we’re turning into “pancake people.”

I haven’t written a love letter in years. To say something to J. now, all I need to do is cross the room. But I don’t think I say as much to him now as I said then. We used to spend hours alone with each other – an ocean, two mail carriers, and 80 cents in stamps apart, joined by a piece of paper.

It was paper that gave us the courage to be something in each other’s lives.

Trouw, January 3, 2009. The two excerpts from love letters are from Nelleke Noordervliet, “Ik kan het niet langer verbergen: over liefdesbrieven” (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, 1993). The translations are mine.

About the author:

Julie Phillips is a biographer, book critic, and essayist who moved from New York to Amsterdam to live with “J.” They recently celebrated their twentieth anniversary.

See: http://julie-phillips.com/wp/

James Tiptree, Jr.: The Double Life of Alice B. Sheldon:

http://www.amazon.com/James-Tiptree-Jr

Nicholas Carr: http://www.nicholascarr.com/