International Pressure Is The Only Way To Halt Israel’s Devastation Of Gaza

Tariq Kenney-Shawa of Al-Shabaka warns Palestinians are being deemed “subhuman” by Israel and the U.S.

Tariq Kenney-Shawa of Al-Shabaka warns Palestinians are being deemed “subhuman” by Israel and the U.S.

Israel’s ground invasion of northern Gaza has in effect begun, following the Israeli military’s announcement on Friday of its plan to “expand” its ground attacks.

“Explosions from continuous airstrikes lit up the sky over Gaza City for hours after nightfall,” according to the Associated Press, and families with loved ones in Gaza were terrified to learn on Friday that Israel has taken down internet and communications throughout the region, largely cutting off contact between the 2.3 million people who live there and the outside world, and making it difficult for journalists to track the scale of ground attacks. According to the Washington Post, “The Hamas media center reported heavy nighttime clashes with Israeli forces at several places, including what it said was an Israeli incursion east of Bureij. Asked about the report, the Israeli military reiterated early Saturday that it had been carrying out targeted raids and expanding strikes with the aim of ‘preparing the ground for future stages of the operation.’”

This is an escalation of the massive retaliatory strikes that Israel has been taking against the population of Gaza since October 7, when an attack led by the militant group Hamas killed roughly 1,400 people inside Israeli territory, including many civilians. The collective punishment that Israel has wreaked in response has destroyed much of Gaza’s infrastructure and has already killed more than 7,000 Palestinians, including 3,000 children.

In the exclusive interview for Truthout that follows, Tariq Kenney-Shawa, policy fellow at the independent transnational think tank Al-Shabaka, the Palestinian Policy Network evaluates the prospects for a shift in United States foreign policy toward Israel and explains why Palestinian resistance will never die as long as Israel fails to recognize Palestinian rights under international law.

C.J. Polychroniou: Gaza, home to 2.3 million Palestinians, has been under direct Israeli occupation for nearly 40 years and has been under blockade for the last 16 years while Israel has retained exclusive control over Gaza’s airspace and territorial waters. Since 2006, which is when Hamas won the last legislative election, Gaza has also been subjected to numerous deadly Israeli assaults. The latest round of massive bombardments, which is taking place in the context of an Israeli plan for the “complete siege” of Gaza and has already resulted in the death of more than 7,000 Palestinians, including 3,000 children, are in response to the unprecedented October 7 Hamas attacks on Israeli territory. Hamas fighters killed as many as 1,400 people and seized perhaps as many as 200 hostages. What do you think Hamas hoped to gain with its attacks on Israeli civilians, which, unsurprisingly, have triggered a massive retaliation with the stated goal of destroying Hamas while employing collective punishment as a method of war?

Tariq Kenney-Shawa: To be honest, I think Hamas was as surprised as many of us in the sheer success and scope of their operation. I don’t believe even Hamas’s leaders and those closest to the operational planning expected that they would get as deep into Israel as they did, and perhaps more importantly, that other rival groups were also able to participate at the level they did. This means that Hamas exercised little operational control on the ground once the scope of the operation exceeded the expected parameters. A lot of the killing of civilians took place in the chaos of the unexpected advance in which fighters found themselves in places they never imagined they would, and reports continue to emerge that the indiscriminate response by Israeli forces also contributed to the civilian death toll.

Again, the October 7 operation was unprecedented in just about every sense of the term, especially in terms of overturning the idea that the Israeli military is inherently invincible. Of course, the power asymmetry between the Israeli military and even the most capable Palestinian resistance groups is immense. Israel is a nuclear-backed force that fields the most advanced weapons (like F-35 fighter jets, Merkava battle tanks, advanced spyware, etc.) on the market and an army that is widely recognized as one of the most capable in the world. But the al-Qassam Brigades were able to take Israeli forces by surprise. So, it’s very clear that what happened on the ground on October 7 likely exceeded what Hamas even intended in the first place.

In terms of the wider strategy, we can speculate on what Hamas hoped to achieve, even if what happened went a lot further. Hamas has come to understand that Israel only communicates, understands and responds to the language of force and violence. Palestinians in Gaza have watched as they become increasingly isolated from the rest of Palestine and the world within the open-air prison that the Gaza Strip is. They have watched political tracks dissolve, they have seen peaceful protesters get sniped by Israeli regime forces, and they have also seen growing international solidarity with the Palestinians translate into nothing but tighter blockade and occupation.

It’s pretty clear that Hamas no longer cares about winning the hearts and minds of the international community, because after more than 75 years of occupation and 16 years of suffocating blockade, those public opinion victories have brought the people of Gaza nothing tangible. To Hamas, disrupting the Israel-imposed status quo is the only thing that gives them leverage, and what that looks like is armed resistance. The truth is that armed resistance played an integral role in forcing Israel to withdraw settlers from Gaza in 2005 and can be argued to have even forced Israel’s hand over recent years in easing aspects of the blockade of Gaza when it comes to expanded fishing zones and the entry of goods.

Hamas knows that Israel will respond with disproportionate force to any act of resistance, but it seems that their goal was to break the status quo at whatever the cost because to them, it is a matter of dying on their feet rather than silently on their knees. People outside of Gaza may disagree with their tactics, but it is critical to understand their reasoning. Read more

Elections In Argentina: A Working Class Perspective

Taroa Zúñiga Silva

A few days before the October 22 elections in Argentina, almost 90 percent of the polls indicated that the winner would be Javier Milei, the “insane” candidate of the right—as described by Estela de Carlotto, president of the legendary human rights group Abuelas de Plaza Mayo (Grandmothers of Plaza Mayo). As it turned out, Sergio Massa (of the coalition Unión por la Patria – UP) prevailed over Milei by almost seven points. Massa and Milei will face off on November 19 in the run-off for the presidency of the country with South America’s second-largest economy.

On August 13, Milei prevailed over all the other candidates in Argentina’s primary. In the months between that election and the one in October, Massa—who is the Minister of the Economy in the current government—added three million votes to his tally.

Georgina Orellano, National General Secretary of AMMAR (Asociación de Mujeres Meretrices de Argentina) told me how this phenomenon was experienced in Constitución, the area of Buenos Aires where the main headquarters of her organization is located. Sex workers organized themselves to monitor both electoral processes in the schools where it was their turn to vote. “In the PASO [primary elections],” she told me, “the worrying result was that the UP force came in third and Milei in first place.” However, this time, “we won in almost all the schools in the Constitución neighborhood.” In fact, “in all the polling stations where sex workers supervised the elections, Massa won.”

The Practical and the Theoretical

Elsa Yanaje, marketing director of the Instituto Nacional de Agricultura Familiar, Campesina e Indígena (National Institute of Family, Peasant, and Indigenous Agriculture) and member of the Federación Rural para la Producción y el Arraigo (Rural Federation for Production and Rooting) believes that the result of the PASO (primary election) was linked to two things: on the one hand, Milei’s communications success in being the only candidate who reflected underlying anger or weariness with the country’s economic situation. “It was about saying what is not said,” Yanaje said. That is, “what a citizen angry with the management [of the central government] could think.”

Yanaje said that in the PASO a vote to warn (more than to punish) was given to the current government. A vote that asked: “What kind of methodology are you going to use to reverse the situation or somehow guarantee some basic services?” Argentina is currently facing a strong economic contraction and high inflation rates, which have especially affected “those who were already below the poverty line,” says Yanaje.

In this context, Milei’s proposals “were somehow charming,” but in practice, Yanaje adds, “we knew that [they were] difficult to maintain.” Between the two choices, the leader explains, “What was reversed [with the new election results was]… a decision between the practical and the theoretical.” The theoretical “was what Milei promised with his proposal of dollarization, privatization, etc.” When these promises were analyzed by communities, it was evident that they were impossible to execute. This exercise of analysis, reflection, and debate was what led people to take their votes towards the practical: the candidate who was linked to the popular sectors was Massa, with more egalitarian proposals that appealed to more sectors of the population.

On the other hand, Orellano considers the results of October 22 to also reflect a popular rejection of Milei’s proposal to “take away rights.” “Many of us were born with a basic right to public health, to public education and we cannot conceive of living without them,” Orellano said.

During the last weeks of campaigning, Milei railed against these fundamental rights, including state subsidies to public transportation. “We learned that if the subsidy is removed,” Orellano told me, “we workers could go from paying 70 pesos to more than 1,000.” This type of data generated an awareness that was reflected in recent electoral results.

The Ballot

The second round of elections in Argentina will be held on November 19. Milei, in his first statements after the last elections, declared that his objective is “to put an end to Kirchnerism.” For Orellano, this call seeks to summon the votes of Juntos por el Cambio (Together for Change), the extreme right-wing coalition whose candidate, Patricia Bullrich, took third place in the elections. Milei’s campaign, Orellano explains, was built against Kirchnerism and “against [the] working class and trade unionists.”

Both Orellano and Yanaje are proud of the political work carried out during these elections. In the family, peasant, and indigenous agriculture sector, of which Yanaje is a member, there is no political campaigning, out of respect for the diversity of thought of the people it brings together. However, constant debate, collective analysis, and organization bear fruit. “There was a reflection on what was coming,” she tells me. “We are defining the course of the country, so we had to stand firm. There was a lot of militancy.”

For AMMAR’s women, they campaigned in their neighborhoods, talking to everyone in their neighborhood. “For the second round, we are going to be active in all the provinces where we are organized,” says Orellano. They plan to increase the number of election observers in the schools of the municipalities where AMMAR has a presence. Sex workers are aware of what is at stake with these two antagonistic proposals for the country. “We know what this denialist, fascist, violent, xenophobic, racist discourse represents being against diversity, against women, against feminism, and against the victories of the working class,” Orellano tells me. “So we sex workers are going to do everything in our power to make sure that the next president of Argentina is Sergio Massa.”

By Taroa Zúñiga Silva

Author Bio:

This article was produced by Globetrotter.

Taroa Zúñiga Silva is a writing fellow and the Spanish media coordinator for Globetrotter. She is the co-editor with Giordana García Sojo of Venezuela, Vórtice de la Guerra del Siglo XXI (2020). She is a member of the coordinating committee of Argos: International Observatory on Migration and Human Rights and is a member of the Mecha Cooperativa, a project of the Ejército Comunicacional de Liberación.

Source: Globetrotter

Why Capitalism Cannot Finally Repress Socialism

Richard D. Wolff

Socialism is capitalism’s critical shadow. When lights shift, a shadow may seem to disappear, but sooner or later, with further shifts of light, it comes back. Capitalism’s ideologues have long fantasized that capitalism would finally outwit, outperform, and thereby overcome socialism: make the shadow vanish permanently. Like children, they bemoan their failure when, in the light of new social circumstances, the shadow reappears clear and sharp. Recent efforts to dispel the shadow having failed again, the contest of capitalism versus socialism resumes. In the United States, young people especially applaud socialism so much recently that think tanks like PragerU and the Hoover Institute at Stanford University urgently recycle the old anti-socialist tropes.

In fact, the capitalism-versus-socialism contest does not really resume because it never really stopped. As changing social conditions changed socialism—a process that took time—it sometimes seemed to wishful thinkers that the systems struggle had ended with capitalism’s victory. Thus the 1920s saw anti-socialist witch hunts (especially the Palmer raids by the U.S. Department of Justice and the Sacco and Vanzetti persecution) that many believed at the time would extinguish U.S. socialism. What had happened in Russia in 1917 would not be allowed to sneak into the United States with all those European immigrants. The grossly unfair Sacco and Vanzetti trial (recognized as such even by the state of Massachusetts) did little to prevent—and much to prepare for—subsequent similar anti-socialist efforts by government officials in the United States.

With the 1929 crash, socialism revived to become a powerful movement in the United States and beyond during the 1930s and 1940s. After World War II ended, the political right and most major capitalist employers tried once again to squash capitalism’s socialist shadow. They fostered McCarthy’s “anti-communist” crusades. They executed the Rosenbergs. By the end of the 1950s, once again, many in the United States could indulge the thought that capitalism had vanquished socialism. Then the 1960s upset that indulgence as millions—especially young people—enthusiastically rediscovered Marx, Marxism, and socialism. Shortly after that, the Reagan and Thatcher reaction tried a bit differently to resume anti-socialism. They simply asserted and reasserted to a receptive mass media that “there is no alternative” (TINA) to capitalism any longer. Socialism, where it survived, they insisted, had proved so inferior to capitalism that it was fading in the present and possessed no future. With the 1989 collapse of the USSR and Eastern Europe, many again believed that the old capitalism versus socialism struggle had finally been resolved.

But of course, the shadow returned. Nothing more surely secures the future of socialism than the persistence of capitalism. In the United States, it returned with Occupy Wall Street, then Bernie Sanders’s campaigns, and now the moderate socialists bubbling up inside U.S. politics. Each time Trump and the far right equate liberals and Democrats with socialism, communism, Marxism, and anarchism, they help recruit new socialists. Socialism’s enemies understandably exhibit their frustration. With so little exposure to Hegel, the idea that modern society might be a unity of opposites—capitalism and socialism both reproducing and undermining one another—is not available to help them understand their world. Read more

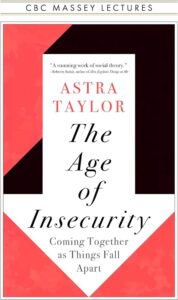

Insecurity Is A Feature, Not A Bug, Of Capitalism. But It Can Spark Resistance

Astra Taylor – Photo: en.wikipedia.org

Debt abolitionist Astra Taylor discusses how capitalism’s manufactured insecurity can feed movements for radical change.

Capitalism is a socioeconomic system that depends upon exploitation and generates inequality. In a recently published book titled, The Age of Insecurity: Coming Together as Things Fall Apart, filmmaker, writer and political organizer Astra Taylor also describes capitalism as an inherently insecurity-producing machine.

From education and home ownership to workplace surveillance, capitalism manufactures insecurity, argues Taylor, a co-founder of the Debt Collective. This insecurity makes us increasingly vulnerable to economic uncertainty, which the system weaponizes in turn against us.

Yet, Taylor argues in the exclusive interview for Truthout, the system’s manufactured insecurity can also band people together to demand radical reforms, although insecurity in today’s world seems to be drawing people increasingly toward authoritarian political leaders.

C. J. Polychroniou: It is often said we live in strange and dangerous times. Indeed, there are crises in place which threaten human survival; there is continuous growth in economic inequality since the 1980s and authoritarianism is on the move as democracy weakens. In this context, in your recently published book aptly titled, The Age of Insecurity: Coming Together as Things Fall Apart, you have described insecurity as a “defining feature of our time” and an essential feature of the capitalist system. Now, capital reigns, to be sure, and capitalism exploits insecurities, but isn’t occasional insecurity also a natural part of life? Why make insecurity a driving force behind today’s economy and politics? Why not resentment, or protest actions, which are growing throughout the world, although some studies indicate that the same thing is happening with political apathy?

Astra Taylor: Insecurity relates to the many intensifying and intersecting crises we face today — unaffordable housing, rising debt, toxic media, worsening mental health, an emboldened far right, climate catastrophe, Artificial Intelligence and Big Tech, the list goes on.

I wouldn’t say that I “make” insecurity a driving force behind today’s politics. I’d argue that it just is one. That’s because, as I show in the book, insecurity is a defining component of capitalism — one as essential as the profit motive. To paraphrase your question, capitalism not only exploits insecurities; more fundamentally, it generates them.

Insecurity, in other words, isn’t just an unfortunate byproduct of our current competitive economic order. It’s a core product. If you aren’t insecure, you don’t keep buying, hustling, accumulating. Insecurity is the stick that keeps us scrambling and striving.

And yet, as you note, insecurity is also a natural part of life.

In the book, I distinguish between two kinds of insecurity. First there is existential insecurity, or the kind of insecurity that is inherent to human life and that stems from the fact we are mortal creatures who can’t survive without the care of others. Then there is what I call manufactured insecurity, and this is the kind of insecurity that is essential to the functioning of a market society.

Looking back over the centuries to the dawn of the industrial era, I show how capitalism began by making people insecure in this modern sense — by severing people from their communities and traditional livelihoods so they had nothing to sell but their labor. We see this dynamic playing out today, as officials pursue monetary policies explicitly designed to weaken the hand of workers. That’s the manufactured insecurity at work.

This might all sound rather heavy, but I really tried to write the book with a light touch — drawing on history and economics while also incorporating myth, psychology and even some humorous memoir elements. And there’s hope. Right now, our society is structured to worsen rather than tend to our insecurities and vulnerabilities. But we can always arrange things differently.

The notion of insecurity as a feature in today’s world might lead people to assume that it leads to despair and inaction. Yet, you argue that insecurity can indeed be a step toward creating solidarity for the purpose of challenging and eventually transforming the system. Is this a theoretical statement behind the purported symbiotic relationship between capitalism and insecurity, or one based on actual empirical evidence? In other words, can you describe how insecurity translates into collective action and what form, in your own view, collective action needs to take for the system to be transformed?

The notion of insecurity as a feature in today’s world might lead people to assume that it leads to despair and inaction. Yet, you argue that insecurity can indeed be a step toward creating solidarity for the purpose of challenging and eventually transforming the system. Is this a theoretical statement behind the purported symbiotic relationship between capitalism and insecurity, or one based on actual empirical evidence? In other words, can you describe how insecurity translates into collective action and what form, in your own view, collective action needs to take for the system to be transformed?

In the book, I argue that insecurity can cut both ways. It can spur defensive and destructive compulsions, or it can be a conduit to empathy, humility, belonging and solidarity. We see this all the time. The right wing knows this and is dedicated to inflaming people’s insecurities, encouraging them to misdirect their rage toward the even-more-vulnerable — rather than toward the economic system and the elites who profit from the status quo.

One example I give is how workers and the unemployed organized during the Great Depression. We forget it today, but “insecurity” was actually a critical concept in the battle for the New Deal. Franklin Roosevelt called insecurity “one of the most fearsome evils of our economic system” and made the concept of security a cornerstone of the welfare state. I certainly see insecurity — shame, fear, anxiety about the future — transformed into solidarity in my work with the Debt Collective, the union for debtors that I helped found.

In today’s economic climate, the rental housing crisis has become particularly acute in thoroughly neoliberal societies like the United States, but rents have also exploded across Europe and more and more people are facing precarious living conditions. Are there innovative solutions for the rental housing crisis? For example, can Vienna’s social housing policy be duplicated in countries like the United States?

Absolutely. I spend some time on the example of Austrian social housing in the second chapter of the book. It’s a fantastic example of how to eradicate a form of material insecurity that is now depressingly endemic across North America.

In the book, I return again and again to a core paradox. As I write, “Today, many of the ways we try to make ourselves and our societies more secure — money, property, possessions, police, the military — have paradoxical effects, undermining the very security we seek and accelerating harm done to the economy, the climate, and people’s lives, including our own.”

Housing really is a prime example. In the U.S., a paltry 1 percent of housing is provided on a non-market basis. The commodification of housing ensures that huge numbers of people will be priced out and perpetually insecure and also unhoused. The very thing that we are told will finally guarantee us security — a mortgage on a one-family unit — also helps drive the destabilization of our communities. Ever-appreciating values and rents push working-class people out of their towns and neighborhoods. Single-family, car-dependent fiefdoms are ecologically wasteful. Not to mention the way the financial sector and the rise of Wall Street landlords are further enriched by this model, further contributing to volatility. Social housing is the only way out of this conundrum, and the only way to ensure real housing security for all.

The Biden administration has made inroads on student debt, but student debt cancellation is still far from becoming a reality, largely because of the Supreme Court’s ultraconservative majority. First, I would like you to explain to readers why the Debt Collective, which you co-founded in 2014 and which happens to be the first union for debtors, talks about “debt cancellation” and rejects the term “debt forgiveness,” and then whether you remain optimistic that an ultimate victory for student-loan borrowers is going to happen at some point down the road.

We reject the idea of “debt forgiveness” because debtors did nothing wrong. People don’t need to be forgiven for pursuing an education — for wanting to learn or to better their lives. This is why the Debt Collective prefers to speak of debt “cancellation,” “relief” or “abolition.”

Our small-but-mighty movement has come a long way in a decade. I believe that we will win — if people get off the sidelines and join us. One easy way people reading can do that is by taking 10 minutes to submit a dispute to the Department of Education using our new Student Debt Release Tool. Anyone with federal loans can do so. The tool will send a former letter demanding relief to the top brass at the Department of Education. The more applications they receive, the more pressure we can apply.

We’ve had victories, we’ve had setbacks, and then more victories and setbacks. I’ve been in the trenches long enough to know that’s how movements go. The arc of justice is, sadly, rather crooked and sometimes loops back on itself. But this is not a moment to throw up our hands — it’s one to keep holding the president’s feet to the fire. The movement for debt abolition is just getting started.

Copyright © Truthout. May not be reprinted without permission.

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

C.J. Polychroniou is a political scientist/political economist, author, and journalist who has taught and worked in numerous universities and research centers in Europe and the United States. Currently, his main research interests are in U.S. politics and the political economy of the United States, European economic integration, globalization, climate change and environmental economics, and the deconstruction of neoliberalism’s politico-economic project. He is a regular contributor to Truthout as well as a member of Truthout’s Public Intellectual Project. He has published scores of books and over 1,000 articles which have appeared in a variety of journals, magazines, newspapers and popular news websites. Many of his publications have been translated into a multitude of different languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Croatian, Dutch, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish. His latest books are Optimism Over Despair: Noam Chomsky On Capitalism, Empire, and Social Change (2017); Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet (with Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin as primary authors, 2020); The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic, and the Urgent Need for Radical Change (an anthology of interviews with Noam Chomsky, 2021); and Economics and the Left: Interviews with Progressive Economists (2021).

“Capitalism Is an Insecurity Machine”: Astra Taylor on Student Debt & Our Radically Unequal World

As the COVID-19 era pause on federal student debt payments comes to an end and some 40 million Americans will resume payments next month, we speak with Debt Collective organizer Astra Taylor about Biden’s new Saving on a Valuable Education, or SAVE, plan and her organization’s new tool that helps people apply to the Department of Education to cancel the borrower’s debt. Taylor also discusses her new book, The Age of Insecurity: Coming Together as Things Fall Apart, in which she writes, “How we understand and respond to insecurity is one of the most urgent questions of our moment, for nothing less than the future security of our species hangs in the balance.” She notes organizing is about “the alchemy of turning our vulnerabilities, turning our oppression, turning our insecurities into solidarity so that we can change the structures that are undermining our self-esteem and well-being.”

Democracy Now! is an independent global news hour that airs on over 1,500 TV and radio stations Monday through Friday. Watch our livestream at democracynow.org Mondays to Fridays 8-9 a.m. ET.

The Case For Protecting The Tongass National Forest, America’s ‘Last Climate Sanctuary’

Tongass National Forest. – Photo: en.wikipedia.org

The “lungs of North America,” the Tongass National Forest is the Earth’s largest intact temperate rainforest. Protecting it means protecting the entire planet.

Spanning 16.7 million acres that stretch across most of southeast Alaska, the Tongass National Forest is the largest national forest in the United States by far and part of the world’s largest temperate rainforest. Humans barely inhabit it: About the size of West Virginia, the Tongass has around 70,000 residents spread across 32 communities.

A vast coastal terrain replete with ancient trees and waterways, the Tongass is a haven of biodiversity, providing critical habitat for around 400 species, including black bears, brown bears, wolves, bald eagles, Sitka black-tailed deer, trout, and five species of Pacific salmon.

The Tongass is a pristine region that supports a vast array of stunning ecosystems, including old-growth forests, imposing mountains, granite cliffs, deep fjords, remnants of ancient glaciers that carved much of the North American landscape, and more than 1,000 named islands facing the open Pacific Ocean—a unique feature in America’s national forest system.

The Tongass “is the crown jewel of America’s natural forests,” declared then-Senator Barbara Boxer (D-CA) during Senate deliberations of Interior Department budget appropriations in 2003. “When I was up there, I saw glaciers, mountains, growths of hemlock and cedar that grow to be over 200 feet tall. The trees can live as long as a thousand years.”

The National Forest Foundation calls the Tongass National Forest “an incredible testament to conservation and nature.” But since the 1950s, the logging industry has prized the forest, and the region has been threatened by companies that seek to extract its resources—and the politicians who support these destructive activities.

America’s Largest Carbon Sink

Carbon sinks absorb more carbon from the atmosphere than they release, making them essential to maintaining natural ecosystems and an invaluable nature-based solution to the climate crisis. Between 2001 and 2019, the Earth’s forests safely stored about twice as much carbon dioxide as they emitted, according to research published in 2021 in the journal Nature Climate Change and available on Global Forest Watch.

The planet’s forests absorb 1.5 times more carbon than the United States emits annually—around 7.6 billion metric tons. Consequently, maintaining the health of the world’s forests is central to humanity’s fight against climate change. But rampant deforestation and land degradation are not only removing this invaluable climate-regulating ecosystem service and supporter of biodiversity but also disturbing a healthy, natural planetary system that has existed for millennia.

“There is a natural carbon cycle on our planet,” said Vlad Macovei, a postdoctoral researcher at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon in Germany. “Every year, some atmospheric carbon gets taken up by land biosphere, some by the ocean, and then cycled back out. These processes had been in balance for the last 10,000 years.” Read more