Minouche Shafik – Samen – Een nieuw sociaal contract voor de 21e eeuw

‘Wij hebben een nieuw sociaal contract nodig dat beter in elkaar zit, dat zekerheid en kansen biedt voor iedereen. Een sociaal contract dat minder gaat over ‘mij’ en meer over ‘wij’, dat onze onderlinge afhankelijkheid onderkent en daar tot ons wederzijds profijt gebruik van maakt.’

Het huidige sociale contract staat onder druk. Het is het moment om tot een eerlijker sociaal contract te komen, het lijkt alsof we het huidige neoliberalisme in bepaalde mate achter ons willen laten, aldus Minouche Shafik. Ons sociaal contract is bezweken onder de druk van technologische en demografische veranderingen. Ze hebben onze wereld ingrijpend getransformeerd, met gevolgen voor inkomensverschillen, gendergelijkheid, onderwijs, gezondheidszorg en werk. We leven steeds vaker in een je-staat-er-alleen voor samenleving, hetgeen niet alleen onrechtvaardig is, maar ook veel minder efficiënt en productief dan wanneer de risico’s worden gespreid over de hele samenleving.

Minouche Shafik neemt ons mee door de stadia van het leven- opvoeden van kinderen, volgen van onderwijs, ziek worden, oud worden- en maakt duidelijk hoe we onze samenleving in elk stadium en op elk niveau kunnen herordenen.

Ze pleit voor zekerheid voor iedereen middels een gegarandeerd minimuminkomen, recht op onderwijs, basisgezondheidszorg en bescherming tegen armoede tijdens de ouderdom.

Ze pleit voor een maximaal investeren in capaciteiten zodat de productiviteit wordt verhoogd, onder andere met hulp van digitale techniek in bijvoorbeeld de gezondheidszorg.

Er is ook veel ongebruikt talent van opgeleide vrouwen, minderheden en kinderen uit arme gezinnen. En ze pleit voor een eerlijke en efficiënte spreiding van risico’s. In het toekomstige sociaal contract zal toenemende flexibiliteit in arbeidskrachten gecombineerd moeten worden met meer zekerheid. Jonge mensen moeten worden erkend in een sociaal contract tussen de generaties, zij die nu leven moeten iets doen aan de erfenis van milieuschade (we hebben een veel te grote aanslag op het milieu gepleegd) en staatsschulden.

Iedereen moet zo lang mogelijk een bijdrage leveren aan de samenleving en burgers zullen ook meer verantwoordelijkheid moeten nemen voor hun gezondheid.

Ze stelt zichzelf de vraag hoe we nieuw sociaal contract moeten financieren in een richting die haalbaar is. Betekent een nieuw sociaal contract een enorme toename van de overheidsuitgaven en een sterke verhoging van de belastingen om een gesubsidieerde kinderopvang, voorschoolse educatie en permanente scholing, toegankelijke gezondheidszorg en een staatspensioen mogelijk te maken? Shafik ziet een deel van deze uitgaven als investering, die in de toekomst hogere belastinginkomsten zullen genereren, maar ook het milieu zullen verbeteren. Dat biedt de mogelijkheid kapitaal te lenen. Een aantal posten keren echter steeds terug, zoals pensioenen en een deel van de gezondheidszorg. Deze kosten moeten daarom worden gefinancierd uit belastingheffing, tenminste in de hoogontwikkelde landen.

Om de klimaatverandering af te remmen moeten we Co2-belasting heffen.

Een nieuw sociaal contract vraagt ook een andere rol van overheid en bedrijfsleven. Het bedrijfsleven zou zich moeten richten op meer winnaars door te investeren in onderwijs en vaardigheden, door achtergebleven regio’s te voorzien van een betere infrastructuur en door innovatie en productiviteit te bevorderen. De overheid zal verantwoordelijk moeten zijn voor een minimaal stelsel van voorzieningen, die iedereen beschermen tegen grote tegenslagen en die worden betaald uit de belastingen, aldus Shafik. De belastingdruk moet verschuiven zodat een gelijker speelveld ontstaat tussen kapitaal en arbeid. Er moet worden opgetreden tegen het ontwijken van vennootschapsbelasting.

De ontwikkeling van het sociaal contract is in de meeste landen afhankelijk van de structuur van het politieke bestel, de effectiviteit van de controlerende mechanismen, de opkomst van politieke coalities en de kansen die voortkomen uit crises, zoals nu de coronacrisis, waarbij vooral de meest kwetsbaren lijden onder de pandemie en het heeft laten zien wat de zwakke plekken zijn van de gezondheidszorg en ouderenzorg. Landen met een presidentieel en meerderheidsstelsel en autoritaire regimes kennen meestal een kleiner overheidsapparaat en een minder genereus sociaal contract. Er zijn minder prikkels om rekening te houden met minderheden. Landen met een stelsel van evenredige vertegenwoordiging en die inclusiever zijn bieden de beste kansen voor een goed functionerend sociaal contract.

De coalitie voor een nieuw sociaal contract is in potentie groot en divers. Jonge mensen zijn gemobiliseerd door middel van acties voor een beter milieu en de mogelijkheden van een levenslang onderwijstegoed, als compensatie voor wat ze zijn kwijtgeraakt. Mensen zonder vast contract zullen vaker om zekerheid, opleidingen en omscholingsmogelijkheden gaan vragen. Het belang van een toegankelijke gezondheidszorg, het aanmoedigen van preventiemaatregelen zijn aangetoond in de pandemie.

De coalitie voor een nieuw sociaal contract is in potentie groot en divers. Jonge mensen zijn gemobiliseerd door middel van acties voor een beter milieu en de mogelijkheden van een levenslang onderwijstegoed, als compensatie voor wat ze zijn kwijtgeraakt. Mensen zonder vast contract zullen vaker om zekerheid, opleidingen en omscholingsmogelijkheden gaan vragen. Het belang van een toegankelijke gezondheidszorg, het aanmoedigen van preventiemaatregelen zijn aangetoond in de pandemie.

In Samen draagt Minouche Shafik de bouwstenen aan voor een nieuw sociaal contract, waarin meer onze onderlinge afhankelijkheden wordt onderkend, meer in mensen wordt geïnvesteerd, maar ook meer van individuen wordt verwacht.

Minouche Shafik – Samen. Een nieuw sociaal contract voor de 21 e eeuw. Uitgeverij Nieuw Amsterdam, Amsterdam, 2021. ISBN: 9789046826799

Minouche Shafik is directeur van de London School of Econimics and Political Science. Ze was vicepresident van de Wereldbank en bekleedde hoge posities bij het IMF en de Bank of England.

Zie ook:

Professor Amartya Sen, Lamont University Professor and Professor of Economics and Philosophy, Harvard, deliver a Distinguished Public Lecture on 18 January 2017 in the Sheldonian Theatre: Democracy and Social Decisions

www.ophi.org.uk

Linda Bouws – St. Metropool Internationale Kunstprojecten

The World Trade Organization Is Threatening Vaccine Equity And Climate Goals

The huge COVID-19 vaccine supply gap between rich and poor countries exposes the deadly problem of intellectual property (IP) rights and the dangerous monopoly power of Big Pharma. It also exposes in glaring terms the failures of the entire system of global trading rules regulated by the World Trade Organization (WTO). In this exclusive interview for Truthout, Jayati Ghosh, one of the world’s leading development economists, dissects the question of intellectual property rights relating to vaccines and argues that the WTO is a vehicle for international imperialism. Ghosh taught economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, for nearly 35 years, and has been professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst since 2021. This year, the United Nations named her to be on the High-Level Advisory Board on Economics and Social Affairs.

C.J. Polychroniou: The COVID-19 health disaster brought to the surface a multitude of issues, problems and faults associated with the workings of a capitalist world, not least of which are the rules of the WTO overintellectual property rights relating to vaccines. What are the facts and the myths behind WTO’s intellectual property rules?

Jayati Ghosh: Intellectual property is governed at the global level by a World Trade Organization treaty called the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement. This agreement was itself the result of active corporate lobbying: Susan Sell has provided a detailed and devastating account of how 12 powerful men from pharma, software and entertainment effectively lobbied to make the U.S. government insist on inclusion of this agreement in the set of agreements negotiated at the Uruguay Round of GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade), which was signed in 1994. The TRIPS agreement intervened in legal systems of all member countries, by putting the burden of proof on the accused rather than the accuser, adopting a much looser definition of “invention” that allowed much more private control of knowledge, and then by making all the rules much stricter and more stringent so that it became much easier to claim infringement. This effectively grants a monopoly over knowledge that companies can use to limit production and increase their own market power. Over the past decades, this has become a major limitation on the dissemination of knowledge and technology for the common good, and essentially benefited large companies who now hold most of the IP rights in the world.

Patents and other intellectual property rules are usually seen as providing a necessary financial reward for invention/innovation, without which technological change would either not occur or be more limited. The pharma industry argues that costs of developing new drugs are very high and there are high risks involved, because the drugs may not succeed even after years of effort, and so they must be granted property rights over this knowledge and be allowed to charge high prices thereafter.

But actually, pharma companies typically only do the “last mile” research for most drugs, vaccines and therapeutics: the bulk of the research — not just the basic science, but also more advanced discoveries that enable breakthroughs — is publicly funded. Big companies increasingly just acquire promising compounds and other knowledge from labs and smaller companies that benefit from public investments. Pharma companies in the U.S., for example, have spent relatively little on R&D — much less than they spend on advertising and marketing, and a small fraction of what they pay out to shareholders or spend in share buybacks designed to increase stock prices.

In addition, in the specific case of COVID-19 vaccines, big pharma companies not only benefited from prior publicly funded research and reduced costs of clinical testing because of more unpaid volunteers for trials, they received massive subsidies from governments that have mostly covered their R&D costs. In the U.S. alone, the six major vaccine companies received over $12 billion in public subsidies; other rich-country governments also provided subsidies to these companies for developing these vaccines. Yet the companies were granted exclusive rights over this knowledge, which they are now using to limit supply and keep prices high even as the global pandemic rages on in the developing world.

Consider the AstraZeneca vaccine, developed by a publicly funded lab in Oxford University. The original distribution model was for an open-license platform, designed to make the vaccine freely available for any manufacturer. However, the Gates Foundation, which had donated $750 million to Oxford for health-related research, persuaded the university to sign an exclusive vaccine deal with AstraZeneca that gave the pharmaceutical giant sole rights. The company promised not to make profits on the vaccine during the pandemic, but because of the competition for doses and opacity in contracts, the range of reported prices of vaccines is vast, from $2.19 to as much as $40 per dose. The major pharma companies producing COVID-19 vaccines are already estimating massive super-profits in 2021 because of the artificially created shortage [effected by the] control over knowledge.

In October 2020, South Africa and India proposed a waiver of IP rights for COVID-19 vaccines. In an unexpected but welcome move, the Biden administration also backed the waiver and encouraged other countries to do the same on account of some extraordinary circumstances at play. The move has now received support from over 120 countries, but it has been opposed by pharmaceutical companies. Should the waiver be temporary, or apply permanently to all private patents on technologies, knowledge and vaccines related to COVID-19 and vital medicines?

India and South Africa requested the WTO to allow all countries to choose to neither grant nor enforce patents and other IP related to COVID-19 drugs, vaccines, diagnostics, and other technologies for the duration of the pandemic, until global herd immunity is achieved. This waiver would apply only to COVID-19-related vaccines, drugs and treatments; it does not mean a waiver from all TRIPS obligations. They could also more easily collaborate in research and development, technology transfer, manufacturing, scaling up and supplying COVID-19 tools.

This is a very limited demand, which develops the argument already in the TRIPS agreement that intellectual property rules can be waived “in exceptional circumstances.” All it does is to protect countries from having trade-dispute mechanisms brought against them by rich country governments in the WTO — it does not ensure the transfer of the required knowledge, for which further measures are required: for example, by governments forcing the companies that benefited from public subsidies to share their technology with other producers.

Some argue that the TRIPS agreement already contains a clause on compulsory licensing by countries that do have production capacity that provides flexibility on patents. But this is too limited in scope and time-consuming, since it must be done item-by-item between companies, and could then be subject to disputes in the WTO.

Even this very limited demand is being fought tooth-and-nail by pharma companies (and consequently by some rich country governments). It is good news that President Biden has dropped U.S. opposition to this waiver, but several European governments with big pharma companies are still opposing it. This is surprising, because such suspension would also benefit their own populations if it made available more vaccines quickly, and larger supply would reduce costs of additional vaccines, making them cheaper for governments and taxpayers across the world, with hopes of finally bringing the pandemic under control.

This is a system that is broken and needs to be fixed urgently. The only beneficiaries are big pharma companies — people across the world suffer, and so do other businesses, as economic activity cannot recover as long as the virus continues to spread and destroy lives and livelihoods. The current demand for a waiver applies only to this pandemic, but it is clear that the entire system of health-related innovation, which is really subsidized and funded by the public, must be restructured to make sure that it operates for public benefit across the world. Otherwise, future health threats will also be hard to combat collectively. Even the recent report of the UN Secretary General’s High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines had recommended that governments increase their own investment in health-related innovations and ensure wider access to the outcomes by preventing privatization of the knowledge.

What about trade secrets as a class of protected right for intellectual property rights holders? Should they also be suspended?

The current proposal in the WTO correctly asks for a waiver on all intellectual property related to preventive, diagnostic and treatment tools, because many of the restrictions in supply come from other IP rights like those for industrial design and trade secrets.

For example, it has been estimated that there are around 64 different IP rights involved in the production of the mRNA vaccines, which have been licensed to Moderna and Pfizer — but new producers would then have to also apply for all of these licenses. A waiver would solve that problem. But, I repeat that the TRIPS waiver is only a first step. It does not ensure that the requisite knowledge will be shared — for that, further pressure needs to be applied by governments to the concerned companies. Read more

Great Power Competition Is Escalating To Dangerous Levels: An Interview With Richard Falk

Great power competition has emerged as a key priority for U.S. foreign policy under the Biden administration. In fact, we may be already at the start of a new New Cold War, according to Richard Falk, one of the world’s leading scholars in the fields of global politics and international law, in the interview below. Falk has also been a leading activist since the Vietnam war, and has published more than fifty books and thousands of essays. His latest book is a political memoir titled Public Intellectual: The Life of a Citizen Pilgrim (Clarity Press, 2021). Falk is Professor Emeritus of International Law at Princeton University, where he taught for nearly half a century, and Chair of Global Law at Queen Mary University of London.

C. J. Polychroniou: Richard, US foreign policy under the Biden administration is geared toward escalating the strategic competition with both China and Russia. Indeed, the Interim National Strategic Guidance, released in March 2021, makes it abundantly clear that the US intends to deter its adversaries from “inhibiting access to global commons, or dominating key regions” and that, moreover, this work cannot be done alone, as was the case under Trump, but will require the reinvigoration and modernization of the alliance system across the world. Does this read to you like a call for the start of a new New Cold War?

Richard Falk: Yes, I would say it is more than ‘the call’ for a New Cold War, but its start. The focus is presently much more China than Russia, because China is seen by Washington as posing the primary threat, and besides, it regards Russia as a traditional rival while China poses novel and more fundamental challenges. Russia, while behaving in an unsavory manner, dramatized by the crude handling of the opposition figure Alexei Navalny, is seen as manageable geopolitically. Euro-American strategy is to stiffen resistance to Russian pressure being exerted along some of its borders, and as in the Cold War can be handled by refurbished versions of ‘containment’ and ‘deterrence.’

China is another matter entirely. The most serious perceived threats are mainly associated with non-military sectors of Western, and particularly, U.S., primacy, its dominance over a dynamic productive economy, especially with respect to frontier technologies. The remarkable developmental dynamism of the Chinese economy has far outstripped anything ever achieved in the West. The United States Government under Biden seems stubbornly blindsided, seemingly determined to address these Chinese threats as if they could be effectively addressed by a combination of ideological confrontation and as with Soviet Union, containment and deterrence. So far, the Biden response is fundamentally mistaken in its approach, which is to view China as a similar adversary than was the Soviet Union. This Chinese challenge cannot be successfully met frontally. It can only be met by a diagnosis of the relative decline of the West by way of self-scrutiny, selective emulation, and a surge of creative adaptive energies. Such a response needs to be accompanied by a reformist agenda of socio-economic equity, massive infrastructure investment, the adoption of fairer wealth and income tax structures, and a commitment to a style of global leadership that identified the national interest to a greater extent with global public goods. Instead of focusing on holding China in check, the United States would do much better by learning from its successes, and adapting them to the distinctiveness of its national circumstances.

It is to be regretted that the present mode of response to China is dangerous and anachronistic for four principal reasons. Firstly, the mischaracterization of the Chinese challenge betrays a lack of self-confidence and understanding by the American Biden/Blinken foreign policy leadership. Secondly, the chosen path of confrontation risks a fateful clash in South China Seas, an area that according to the precepts of traditional geopolitics falls within the Chinese sphere of influence, and a context within which Chinese firmness is perceived as ‘defensive’ by Beijing while the U.S. military presence is regarded as intrusive, if not ‘hegemonic.’ These perceptions are aggravated by the U.S. effort to augment its role as upholding alliance commitments in South Asia, recently reaffirmed by a clear anti-Chinese animus in the shape of the QUAD (Australia, Japan, India, and the U.S.), formally named Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, which despite the euphemism intends to signify enhanced military cooperation and shared security concerns.

Thirdly, the longtime U.S. military superiority in the Pacific region may not reflect the current regional balance of forces in the East and South China Seas. Pentagon public assertions have been sounding the alarm, insisting that in the event of a military confrontation, China would likely come out on top unless the U.S. resorts to nuclear weapons. According to an article written by Admiral Charles Richard, who currently heads National Strategic Command, this assessment has been confirmed by recent Pentagon war games and conflict simulations.

Taking account of this view, Admiral Richard advises that U.S. preparations for such an armed encounter be changed from the possibility recourse to nuclear weaponry to its probability. The implicit assumption, which is scary, is that U.S. must do whatever it takes to avoid an unacceptable political outcome even if it requires crossing the nuclear threshold. It may be instructive to recall the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 when Soviet moves to deploy defensive missile systems in Cuba in response to renewed U.S. intervention to impose regime change. It is instructive to recall that Cuba was accepted as independent sovereign state entitled under international law to uphold its national security as it sees fit, while Taiwan has been consistently falling within the historical limits of Chinese territorial sovereignty. The credibility of the Chinese claim was given diplomatic weight in the Shanghai point Communiqué that re-established U.S./China relations in 1972. Kissinger recalled that in the negotiations leading to a renewal of bilateral relations the greatly admired Chinese Foreign Minister, Chou En-Lai, was flexible on every issue except Taiwan. That is, China has a strong legal and historical basis for reclaiming Taiwan as an integral part of its sovereign territory considering its armed severance from China as a result of Japanese imperialism. China governed the area now known as Taiwan from 1683-1895. In 1895 it was conquered and ruled by Japan until 1945 when it was reabsorbed and became a part of the Republic of China. After 1949 when the Chinese Communists took over control of China, Taiwan was renamed Republic of China on Taiwan. From the Chinese perspective, this historical past upholds the basic contention that Taiwan is part of China and not entitled to be treated as a separate state.

Fourthly, and maybe decisively, the international claims on the energies and resources of the United States are quite different than they were during the Old Cold War. There was no impending catastrophe resulting from climate change to worry about or decaying infrastructure desperately needing expensive repair or under-investment in social protection by government in the area of health, housing, and education.

On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) – IV How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist [The usefulness of continuous measurement of the distance between Nostalgia and Melancholia] (September 2021 – June 2022)

Introduction

Introduction

In 2021/22 the 100th anniversary of the birth of artist Joseph Beuys will be celebrated in Europe, among others with the special event ‘Beuys 2021. 100 years’. Twelve cities and twenty institutes in North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany will be organizing exhibitions, theatre and other activities to celebrate this anniversary. (see for more info https://beuys2021.de/en).

Joseph Heinrich Beuys (1921, Krefeld- 1986, Düsseldorf) is one of the most influential German post-war artists, who became particularly famous for his performances, installations, lectures and Fluxus concerts. But who was Beuys truly? Joseph Beuys mythologized his war history as a National Socialist and Germany’s problematic and post-traumatic past. After Word War ll Beuys transformed himself from perpetrator to victim. His service in the Luftwaffe did not offset his artistic practice. During this 100-years event none of these controversial aspects of Beuys’ work, values and ideas are focused upon. As part of this celebration it is high time to add a more critical eye on Beuys’ work and his relationship to Germany’s post-war history.

Project

On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV -How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist [The usefulness of continuous measurement of the distance between Nostalgia and Melancholia] (‘Hasenjagd’ is the code word for killing Jews during World War II) centers on Joseph Beuys and Joseph Sassoon Semah takes us on a journey of critical analysis of Beuys. Linda Bouws is the curator.

Art cannot be seen disengaged from society – which political, social and cultural implications does Joseph Beuys’ work show us?

How do work and politics relate in Beuys’ work, what is myth and what is reality? Did Beuys free art of power and financial gain or did he use his art with the purpose to forget or idealize his own war history and that of Germany? Does his transformation from perpetrator to victim fit into post-war Germany? How did Beuys use his ‘visual codes’, that have disappeared, and secret symbols? How must we interpret Beuys in this celebratory year 2021?

Joseph Sassoon Semah has done extensive research into Joseph Beuys’ work, values and ideas and based on this research and texts he will analyse the deeper meaning of the (secret) symbols used by Joseph Beuys for ‘On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV- How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist [The usefulness of continuous measurement of the distance between Nostalgia and Melancholia]’. He will react to them using new monumental sculptures and a series of old and new drawings, performances, texts and meetings.

This project wants to raise public awareness about the missing information on Joseph Beuys. Information that has been disregarded during this celebratory year or has been evaded to avoid uncomfortable confrontations. A new project about the reading of Beuys’ ‘shrouded’ art by the Jewish-Babylonian artist Joseph Sassoon Semah.

We will cooperate with among others with Gerard-Marcks-Haus Bremen, Goethe-Institut Amsterdam, Duitsland Instituut Amsterdam, Lumen Travo Gallery, Redstone Natuursteen & Projects, the Jewish Historical Museum and The Maastricht Institute for the Arts. After completion of the manifestation a complementary publication will be compiled.

Metropool International Art Projects

Contact: Linda Bouws

lindabouws@gmail.com

Mob +31(0) 620132195

Interview: Léonce Ndikumana On Africa And Capital Flight

This is part of PERI‘s economist interview series, hosted by GP Columnist C.J. Polychroniou.

This is part of PERI‘s economist interview series, hosted by GP Columnist C.J. Polychroniou.

C.J. Polychroniou:You studied economics as an undergraduate student in Burundi, but ended up in the United States for your graduate studies. Why economics, and which economic thinkers have had the greatest impact on you?

Léonce Ndikumana: When I enrolled in the Economics Department at the University of Burundi, I was not specifically attracted by any particular school of thought or any economic thinker. Economics was considered one of the challenging majors in the university and the major was perceived as a good path for professional success. But then as I studied economics more, I developed a keen interest in certain areas including economic development. Economics provided me with the framework and the tools to understand the challenges of underdevelopment and constraints to growth. As a son of a farmer, born in one of the least developed countries in the world, development was not just an academic topic, it was about issues that I myself had experienced or witnessed since my early childhood. I found the study of economic development both captivating as well as humbling; humbling in the sense that it gave me a better understanding of my own life path, and better appreciation of every step I had crossed towards building a decent life for myself and my family. Studying economic development is still fascinating to me up to today. But as I grew up and matured as an economist, studying economic development has become also more frustrating as I keep asking the same question of why obvious solutions are not embraced to address problems faced by populations in the developing world. The key to this puzzle is the incentive structures that guide policy making, specifically the distribution of power between those who benefits from the status quo vs. those who would potentially benefit from a change in the system towards generalized improvement in welfare. Countries remain stuck in ‘low-equilibrium’ situations because policy making is hijacked by the interest groups that benefit from the status quo, and when the majority who would benefit from change have no means to voice their concerns. Development and the lack of it are, by and large, a matter of the quality of institutions that govern economic policy making.

CJP: How did you end up teaching at UMass-Amherst?

LN: When I joined the Economics Department at UMass-Amherst in 1996, I was mostly attracted by the work in the Keynesian tradition. My training at Washington University in St. Louis (Missouri) was grounded in the Keynesian tradition, precisely New Keynesian macroeconomics. My dissertation explored the issue of financing firm investment in the context of imperfect markets. Working under my advisor, Professor Steven Fazzari, a premier leader in the field of New Keynesian macroeconomics, I had admired the work of Professor James Crotty, a major figure in Post-Keynesian macroeconomics who had a keen interest in the work on investment. James Crotty was a great mentor for me in my early days as an Assistant Professor; I learned a lot from him, and I will always be grateful for his guidance.

During my graduate training I was also fortunate to study under Nobel Prize winner Professor Douglass North, who taught me to appreciate the role of institutions in the evolution of modern economies. This cemented my interest in understanding the process of economic development. I wrote my field comprehensive exam paper on development in Burundi under his supervision. Once at UMass, I found a strong program in economic development, especially focused on Latin America and Asia. Fortunately, my colleague Jim Boyce gracefully opened his door and invited me to collaborate on research on Africa. That’s when we launched our work on capital flight from Africa, starting with a case study on the Congo under former president Mobutu. This partnership has continued up to today, producing a long series of academic papers and a book. We are currently engaged in research that is more granular and country specific to explores the mechanism of capital flight, including the role of the transnational network of ‘enablers’ composed of banks, major consulting, auditing, and law firms.[1] Our work on capital flight has played an important role in providing evidence to feed the global debate on illicit financial flows, culminating in the enactment by the United Nations of a target to combat illicit financial flows enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goals (Target 16.4). Capital flight remains my main area of research today.

CJP:Africa, you have argued in a 2015 article in African Studies Review, is being integrated yet marginalized in the global economy. Can Africa overcome being marginalized in the age of globalization without a change in global governance?

LN: In 2019, Africa’s total trade was 106 times higher than in 1950. During this period, however, the continent’s share in world trade declined from an unimpressive 6% to a meager 2%. Between 1970 and 2019, foreign direct investment inflows into Africa grew 35 times. But Africa’s share in world FDI dropped from 10% to 3%.[2] Clearly, in absolute terms, it may appear as though Africa has been increasingly ‘integrating’ in the global economy. But in reality, Africa has been growing more marginalized over time: it occupies a much smaller space today than before independence. One major reason is that Africa has failed to transform its economies, and continues to sell its cheap raw material in exchange for increasingly more expensive manufactured products. Technological innovation is lagging, and the continent has lost the competition in the global value chain.

Can it get worse? Unfortunately, yes! Africa can become even more marginalized unless global governance is reformed to accommodate more equitable participation in policy making so that Africa can have a voice to advance and defend its interest. It can get worse also unless there is successful global coalition to promote transparency and accountability in the global trade and financing systems so as to combat tax evasion, trade misinvoicing, banking secrecy, and all other mechanisms that facilitate and enable the plundering of Africa’s natural resources.

CJP: You have researched extensively the problem of capital flight from Africa. Can you briefly summarize the role of both domestic factors and external players in driving capital flight from Africa, as well as explain why, in comparison to other regions, capital flight is a more severe problem for sub-Saharan African countries?

LN: Capital flight from Africa is a major hindrance to efforts to move the continent’s economies to a path of high growth and sustainable development. It drains scarce and valuable resources that could be used to finance investments in public infrastructure, social services such as education and health, and to stimulate innovation and economic transformation.

The causes and drivers of capital flight from Africa are both a domestic and global. On the domestic front, capital flight is induced and facilitated by the breakdown of the regulatory and legal regimes that enable individuals and companies to smuggle goods and money abroad in contravention of customs and exchange controls. Some of the funds illicitly funneled abroad are in fact illicitly acquired through corrupt means by members the economic and political elite that are able to use their power and connections to embezzle public resources and also do so with impunity. Capital flight is therefore a result of the failure of national institutions. But there is also a reverse causation: capital flight erodes the quality of national institutions through habit formation and contagion effects. The orchestrators of capital flight invest in undermining the quality of institutions through corruption to make it easier for them to perpetuate their illicit dealings. These practices, which are typically orchestrated by the elite, are then emulated by private individuals as it becomes evident that the mechanisms of control and accountability are breaking down. As a result, capital flight becomes a self-perpetuating phenomenon: through hysteresis, countries with high capital flight are unable to break through the vicious cycle of financial hemorrhage.

Bonnot in beeld – De Autobandieten in fictie

De geschiedenis van de Autobandieten, de groep gewelddadige anarchisten die in 1911 en 1912 Parijs en daarmee Frankrijk in paniek bracht – zie het korte historische overzicht op Rozenberg Quarterly – zorgde voor tientallen studies naar de sensationele gebeurtenissen tijdens de Belle Époque.

De geschiedenis van de Autobandieten, de groep gewelddadige anarchisten die in 1911 en 1912 Parijs en daarmee Frankrijk in paniek bracht – zie het korte historische overzicht op Rozenberg Quarterly – zorgde voor tientallen studies naar de sensationele gebeurtenissen tijdens de Belle Époque.

Blijkbaar spraken de gebeurtenissen enorm tot de verbeelding want ook in de populaire cultuur is decennia later de erfenis van de Autobandieten terug te vinden.

Het was een middelmatige hit, maar ook een middelmatig nummer: de single La Bande à Bonnot van de Franse chansonnier Joe Dassin, verschenen in het kielzog van de speelfilm La Bande à Bonnot, uitgebracht in 1968. Blijkbaar maakten de Autobandieten toen nog steeds de tongen los, in ieder geval van het ridicule dameskoortje in het nummer van Dassin, die trouwens zelf ook met een misplaatst soort vrolijkheid de daden van de anarchisten bezingt.

De versie die het Franse rockduo Orange Macadam in 2008 (!) van hetzelfde nummer maakte, ligt aanzienlijk beter in het gehoor.

Speelfilm

De speelfilm La Bande à Bonnot uit 1968, geregisseerd door Phillie Fourastié, verdient geen Oscar, zelfs geen vijf sterren, maar acceptabel is de film toch wel. Acteur Bruno Cremèr is te zien als Jules Bonnot (later speelde Cremèr Maigret in de gelijknamige tv-serie uit de jaren negentig), de rol van Raymond Callemin wordt, heel verrassend, gespeeld door Jacques Brel, zijn tweede filmrol ooit. Brel schreef ook de muziek voor de film. Actrice Annie Girardot speelt een van de vrouwen in de groep rond de Autobandieten. Of de film ooit in Nederland is vertoond is niet meer te achterhalen. Wel in België, waar het volledig uitgeschreven filmscenario met dialogen, verscheen in een luxueuze boekenreeks getiteld Filmclub, waarin scenario’s van films werden gepubliceerd: Alexandre le Roi, De bende van Bonnot (uitg. Walter Beckers, Kalmthout-Antwerpen, z.j. waarschijnlijk 1968).

De film geeft een overtuigend sfeerbeeld van het illegalistische milieu van anarchistische activisten rond 1911. Op kleding en haardracht van de acteurs is nog wel iets af te dingen: een tikkeltje te veel jaren-zestig, alsof aansluiting gevonden moest worden met de revolutionaire sfeer in Parijs in de meidagen van 1968.

De acties van de Autobandieten – voor zover te beoordelen – zijn waarheidsgetrouw in beeld gebracht, al is niet gefilmd op de exacte, nog bestaande locaties van de gebeurtenissen.

Bovendien toont de film nogal wat anachronismen. Zo zijn er vuurwapens en bewegwijzering te zien die in 1911 nog niet bestonden en een lied dat door de bandieten wordt gezongen werd pas in 1936 gecomponeerd.

Bovendien toont de film nogal wat anachronismen. Zo zijn er vuurwapens en bewegwijzering te zien die in 1911 nog niet bestonden en een lied dat door de bandieten wordt gezongen werd pas in 1936 gecomponeerd.

Bioscoopscène

Een gemiste kans is een scène in een bioscoop, waar Bonnot en zijn vrienden een Amerikaanse gangsterfilm bekijken, The Gangsters and the Girl. Weliswaar is deze gebaseerd op de belevenissen van de Autobandieten, maar de film dateert uit 1914. Toen waren de meeste leden van de bende al lang om het leven gekomen of geëxecuteerd.

Authentieker zou zijn geweest wanneer de regisseur de bendeleden in de bioscoop naar een contemporaine film over henzelf had laten kijken. Dat had gekund met de korte speelfilm L’Auto grise uit april 1912, gebaseerd op de overvallen van de Autobandieten. Deze film biedt een nauwkeurige reconstructie van de gebeurtenissen. In mei 1912 maakte regisseur Victorin Jasset een tweede film over hetzelfde onderwerp, Hors la loi. Beide films voegde hij later samen tot Les Bandits en automobile. Jasset gebruikte weliswaar niet de daadwerkelijke locaties voor zijn film, maar benadert wel de werkelijkheid. Zo werd de garage waar Bonnot werd belegerd exact nagebouwd. Op Youtube is de film in zijn geheel te zien.

Romans

Het boek La Bande à Bonnot (1968) van de Franse auteur Bernard Thomas is een gefictionaliseerde versie van de geschiedenis van de Autobandieten. De roman is niet in het Nederlands vertaald, wel in het Duits: Anarchisten, Ein Bericht (1970). Thomas verzon natuurlijk de dialogen, maar de historische lijn houdt hij correct aan. De roman In Ogni Caso Nessum Rimorso (1994) van de Italiaanse schrijver Pino Cacucci, in het Engels vertaald als Without a Glimmer of Remorse (Read and Noir Books, 2006), volgt op vergelijkbare wijze de historie, maar leest een stuk minder makkelijk.

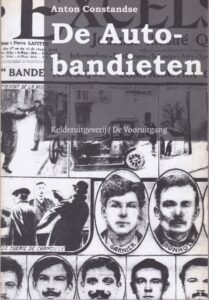

Aan deze twee romans ging lang daarvoor een eerste geromantiseerde versie van het verhaal van de Autobandieten vooraf. De Nederlandse anarchistische propagandist Anton Constandse publiceerde in 1935 De Autobandieten, nog steeds het enige in Nederland gepubliceerde boek over de groep. Het verscheen bij de BOO te Zandvoort, de Bibliotheek voor Ontspanning en Ontwikkeling van anarchistisch uitgever Gerhard Rijnders. De BOO gaf sociale romans uit, populair wetenschappelijke titels en anarchistische teksten.

Aan deze twee romans ging lang daarvoor een eerste geromantiseerde versie van het verhaal van de Autobandieten vooraf. De Nederlandse anarchistische propagandist Anton Constandse publiceerde in 1935 De Autobandieten, nog steeds het enige in Nederland gepubliceerde boek over de groep. Het verscheen bij de BOO te Zandvoort, de Bibliotheek voor Ontspanning en Ontwikkeling van anarchistisch uitgever Gerhard Rijnders. De BOO gaf sociale romans uit, populair wetenschappelijke titels en anarchistische teksten.

Dat Constandse voor de romanvorm koos, lag in het verlengde van de opzet van de BOO: goedkope, leesbare boeken voor iedereen. Een roman was voor veel lezers toegankelijker dan een biografie, een beschrijving van arbeidsomstandigheden of en verhandeling over sociale strijd.

Constandse weet de sfeer in het Franse anarchistische milieu goed te schetsen, iets waar zeker degelijk studiewerk aan ten grondslag moet liggen. Ondanks de daden van de Autobandieten, weet hij enige sympathie op te wekken voor een aantal leden van de groep, zoals voor de jonge Carouy, die vogeltjes kocht op de vogelmarkt, om ze vervolgens los te laten. Hij beschrijft glashelder het tragische element in de geschiedenis: in beginsel waren het goeie jongens en met hun ideeën was in oorsprong niets mis, maar overmoed en onbezonnenheid droegen bij tot hun gewelddadige ondergang.[1]

Strips

Strips

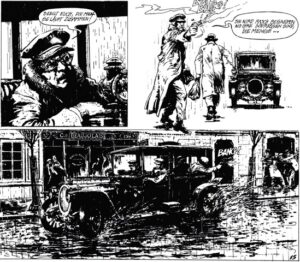

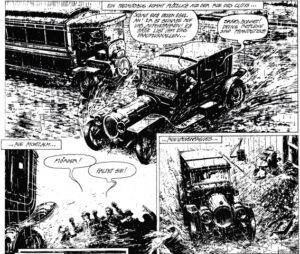

Een waarheidsgetrouwe weergave van het anarchistische wereldje ontbreekt in de strip La Bande a Bonnot van de Spaanse makers Clavé en Godard, in het Duits verschenen als Viel Blut für teures Geld (Karin Kramer Verlag 1990). De strip is een mooi filmisch verslag van de affaire, het leest als het storyboard voor een film. Auto’s, gebouwen en straatscènes zijn tot in detail perfect getekend, maar de personages blijven afstandelijke, kartonnen figuren.

Dat geldt ook voor het stripverhaal Geen god, geen meester. Een avontuur van de Tijgerbrigades van Harald Kivits (2006). Deze bewerking van een aflevering van de Franse televisieserie Les Brigades du Tigre, is gebaseerd op een door de Franse premier Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) – bijgenaamd Le Tigre – ingestelde politie-eenheid die recht en orde moest herstellen in het Frankrijk van begin vorige eeuw. In werkelijkheid heeft de Tijgerbrigade van Clemenceau nooit tegenover de Autobandieten gestaan.

Chansons

Chansons

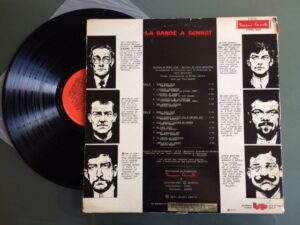

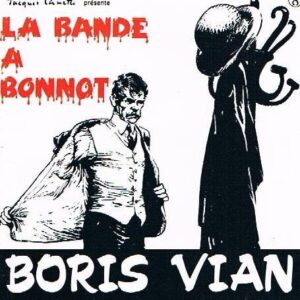

Het koortje bij Joe Dassin mag dan lekker doorzingen, in de chansons die de Franse kunstenaar, schrijver, trompettist en jazzcriticus Boris Vian (1920-1959) over de Autobandieten schreef, gaat het er een stuk filosofischer en socialer aan toe. Vian zong de chansons op de elpee La Bande à Bonnot niet zelf, maar de nummers werden op muziek gezet door Louis Bessières en verschenen in 1975 op elpee, in een prachtige uitklaphoes met illustraties uit de strip van Clavé en Godard. Voor Vian zijn de Autobandieten niet een stel nietsontziende criminelen, maar hij plaatst hun geschiedenis juist in een sociale context. Zijn boodschap is duidelijk: de maatschappij is de oorzaak van hun acties. Het nummer L’enfant de Bonnot illustreert dat.

Boris Vian: De jeugd van Bonnot

In zijn doodsstrijd beleeft een man zijn verleden,

in de heldere ogen van zijn hond die naast hem sterft,

In 1881, hij was toen vijf jaar, kende hij verdriet om de dood van zijn moeder,

en zijn vader sloeg hem zonder reden keer op keer,

zijn afkeer tegen onrechtvaardigheid werd alleen maar groter,

Zonder de minste tederheid,

zonder de geringste tederheid,

groeide hij op als onkruid dat gewied wordt tussen de stenen,

Zo ging hij door zijn kindertijd,

en vermoedde al dat om zich te verdedigen, zijn blote handen

niet voldoende waren,

Geen enkele onderwijzer begreep hem,

zelfs niet een beetje,

probeerden niet de oorzaken te kennen

waarom hij zo’n ongelukkige indruk maakte,

Men zei al tegen hem: ‘Je moet niet teveel praten…’

‘Het is niet goed dat je hardop zegt wat je denkt,’

De eerste knokpartij,

de buurman die hem verlinkt,

de smerige fabriek en het afgestompende werk,

De tijd van woede,

Toen soldaten schoten op een menigte die betoogde

op een eerste mei,

Wat voorafgaat is niet genoeg om hem te excuseren,

maar men vindt toch een verklaring voor zijn wandaden,

dat in een onrechtvaardige maatschappij,

waarin de vrijheid wegkwijnt,

De maatschappij heeft de criminelen die zij verdient.

– Vertaling chanson: Dick Gevers

Noot:

[1] In 2010 werd het boek van Anton Constandse opnieuw uitgegeven, met een nieuwe, heldere inleiding waarin Dick Gevers de Autobandieten in hun historische en sociale context plaatst: Anton Constandse, De Autobandieten, Kelderuitgeverij/De Vooruitgang 2010, ISBN 9789079395040.