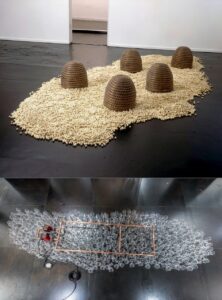

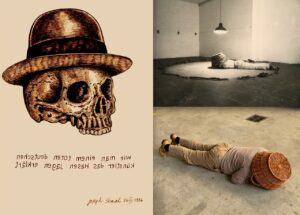

On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV – How to Explain Hare Hunting To A Dead German Artist – Maarten Luther Kerk – Amsterdam

On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV – How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist

On Friendship / (Collateral Damage) IV – How to Explain Hare Hunting to a Dead German Artist

[The usefulness of continuous measurement of the distance between Nostalgia and Melancholia] (september 2021 – december 2022)

A critical project concerning post-war artist Joseph Beuys created by Joseph Sassoon Semah, curator Linda Bouws

Maarten Luther Kerk, Dintelstraat 134, Amsterdam

15 mei 2022, aanvang 15.30 uur, Opening Tentoonstelling, Performance en Bijeenkomst

15 mei t/m 15 juli Tentoonstelling, bezoek op afspraak

Programma 15 mei:

15.30 uur: Welkom Dr. A.H. Wöhle, President Evangelisch-Lutherse Synode in de Protestantse Kerk

15.45 uur: Performance Joseph Sassoon Semah en zijn vrienden en tentoonstelling bezichtigen

16.15 uur: Meeting met o.a. Andreas Wöhle en Joseph Sassoon Semah: Joseph Beuys en Christus impuls

17.15 uur: Afsluitende borrel

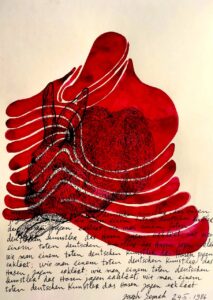

In het werk van kunstenaar Joseph Beuys is de christelijke iconografie een van de belangrijkste thema’s, met name de Christus impuls.

In het werk van kunstenaar Joseph Beuys is de christelijke iconografie een van de belangrijkste thema’s, met name de Christus impuls.

Hij gebruikt objecten die staan voor het geestelijke zoeken, de moderne devotie: de crucifix, een wandelstok, een vogel, een haas.

Door te lijden ontstaat het vermogen tot scheppingskracht “kunst is een geestelijke act die telkens opnieuw moet gebeuren.”

Beuys werd sterk beïnvloed door de antroposoof Rudolf Steiner, “Christus-ich Kraft”. Voor Steiner was de fysieke incarnatie van Jezus aan het begin van de tijdrekening een eenmalige gebeurtenis.

Steiner noemt dit de ‘Christus impuls’ en ‘het mysterie van Golgotha’.

Welk Christusbeeld had Beuys voor ogen? Hoe verhoudt zijn Christusbeeld zich tot zijn kunst?

Welke invloed had Steiner op zijn werk?

Hoe reflecteert Joseph Sassoon Semah in zijn kunstwerken op Joseph Beuys?

Hoe kijkt Andres Wöhle naar Beuys, Steiner en Joseph Sassoon Semah?

Er wordt samengewerkt met o.a. Maarten Lutherkerk, Gerhard-Marcks-Haus Bremen, Goethe-Institut Amsterdam, Duitsland Instituut Amsterdam/UvA, Lumen Travo Gallery, Deutsche Bank, Landgoed Nardinclant-Amsterdamgarden, Redstone Natuursteen & Projecten, Geestelijke Gezondheidszorg AmacuraThe Maastricht Institute for Arts.

Na afloop van de manifestatie wordt een complementaire publicatie samengesteld.

Het project is mede mogelijk gemaakt door het Mondriaan Fonds, het publieke stimuleringsfonds voor beeldende kunst en cultureel erfgoed en Redstone Natuursteen & Projecten.

Noam Chomsky: Propaganda Wars Are Raging As Russia’s War On Ukraine Expands

Since World War I, propaganda has played a crucial role in warfare. Propaganda is used to increase support for the war among citizens of the nation that is waging it. National governments also use targeted propaganda campaigns in an attempt to influence public opinion and behavior in the countries they are at war with, as well as to influence international opinion. Essentially, propaganda, whether circulated through state-controlled or private media, refers to techniques of public opinion manipulation based on incomplete or misleading information, lies and deception. During World War II, both the Nazis and the Allies invested heavily in propaganda operations as part of each side’s overall effort to win the war.

The war in Ukraine is no different. Both Russian and Ukrainian leaders have undertaken a campaign of systematic dissemination of warfare information that can easily be designated as propaganda. Other parties with a stake in the conflict, such as the United States and China, are also engaged in propaganda operations, which work in tandem with their apparent lack of interest in diplomatic undertakings to end the war.

In the interview that follows, leading scholar and dissident Noam Chomsky, who, along with Edward Herman, constructed the concept of the “propaganda model,” looks at the question of who is winning the propaganda war in Ukraine. Additionally, he discusses how social media shape political reality today, analyzes whether the “propaganda model” still works, and dissects the role of the use of “whataboutism.” Lastly, he shares his thoughts on the case of Julian Assange and what his now almost certain extradition to the United States for having committed the “crime” of releasing public information about the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq says about U.S. democratic principles.

Chomsky is internationally recognized as one of the most important intellectuals alive. His intellectual stature has been compared to that of Galileo, Newton and Descartes, as his work has had tremendous influence on a variety of areas of scholarly and scientific inquiry, including linguistics, logic and mathematics, computer science, psychology, media studies, philosophy, politics and international affairs. He is the author of some 150 books and the recipient of scores of highly prestigious awards, including the Sydney Peace Prize and the Kyoto Prize (Japan’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize), and of dozens of honorary doctorate degrees from the world’s most renowned universities. Chomsky is Institute Professor Emeritus at MIT and currently Laureate Professor at the University of Arizona.

C.J. Polychroniou: Wartime propaganda has become in the modern world a powerful weapon in garnering public support for war and providing a moral justification for it, usually by highlighting the “evil” nature of the enemy. It’s also used in order to break down the will of the enemy forces to fight. In the case of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Kremlin propaganda seems so far to be working inside Russia and dominating Chinese social media, but it looks like Ukraine is winning the information war in the global arena, especially in the West. Do you agree with this assessment? Any significant lies or war-myths around the Russia-Ukraine conflict worth pointing out?

Noam Chomsky: Wartime propaganda has been a powerful weapon for a long time, I suspect as far back as we can trace the historical record. And often a weapon with long-term consequences, which merit attention and thought.

Just to keep to modern times, in 1898, the U.S. battleship Maine sank in Havana harbor, probably from an internal explosion. The Hearst press succeeded in arousing a wave of popular hysteria about the evil nature of Spain. That provided the needed background for an invasion of Cuba that is called here “the liberation of Cuba.” Or, as it should be called, the prevention of Cuba’s self-liberation from Spain, turning Cuba into a virtual U.S. colony. So it remained until 1959, when Cuba was indeed liberated, and the U.S., almost at once, undertook a vicious campaign of terror and sanctions to end Cuba’s “successful defiance” of the 150-year-old U.S. policy of dominating the hemisphere, as the State Department explained 50 years ago.

Whipping up war myths can have long-term consequences.

A few years later, in 1916, Woodrow Wilson was elected president with the slogan “Peace without Victory.” That was quickly transmuted to Victory without Peace. A flood of war myths quickly turned a pacifist population to one consumed with hatred for all things German. The propaganda at first emanated from the British Ministry of Information; we know what that means. American intellectuals of the liberal Dewey circle lapped it up enthusiastically, declaring themselves to be the leaders of the campaign to liberate the world. For the first time in history, they soberly explained, war was not initiated by military or political elites, but by the thoughtful intellectuals — them — who had carefully studied the situation and after careful deliberation, rationally determined the right course of action: to enter the war, to bring liberty and freedom to the world, and to end the Hun atrocities concocted by the British Ministry of Information.

Beeldvorming in Berichtgeving; Joden toen en Moslims nu

Inleiding

Inleiding

“Heb ik, in strijd met uw verwijt, de Nederlandsche gastvrijheid in het verleden dankbaar herdacht. Thans echter is van gastvrijheid geene sprake meer, want gij en ik zijn beide staatsburgers met gelijke rechten en plichten. Ik ben niet uw gast en gij zijt niet mijn gastheer – maar gesteld eens, gij waart het, dan neemt gij de honneurs al vrij gebrekkig waar” (Open brief van A.C. Wertheim aan L.W.C. Keuchenius. Algemeen Handelsblad, 24 januari, 1891).

“Ik vraag me af of we pas acceptabel zijn voor de VVD als we ons geloof vaarwelzeggen. Moeten we eerst vrijzinnig worden. Wij zijn geen gastarbeiders en al helemaal geen gast. Wij zijn Nederlanders” (Karacaer, 2004).

Met het “Ik ben niet uw gast en gij zijt niet mijn gastheer” reageert het liberale Eerste Kamerlid Wertheim (1832-1897) via een open brief vol zelfvertrouwen op de verwijten van het antirevolutionaire Tweede Kamerlid Keuchenius (1822-1893). Subtiel laat Wertheim weten dat hij niet gediend is van de door Keuchenius toebedachte positie van joden, aan het einde van de 19de eeuw, als gasten en tweederangsburgers in de Nederlandse samenleving. Zij zijn staatsburgers met gelijke rechten en plichten. Een vergelijkbaar citaat “Wij zijn geen gastarbeiders en al helemaal geen gast.” verschijnt ruim een eeuw later in het dagblad Trouw over de positie van moslims in de Nederlandse samenleving. Dit citaat van de toenmalig Milli Görüş directeur Haci Karacaer, is een reactie op het liberale VVD Kamerlid Hirsi Ali. Karacaer maakt door het stellen van de (retorische) vraag of moslims pas acceptabel zijn als ze het geloof vaarwelzeggen, de ervaring vanondergeschiktheid nog zichtbaarder dan Wertheim destijds deed.

Beiden reageren op de positie die zij krijgen toegewezen als gast in de samenleving. Hebben zij dan geen gelijke rechten, zoals Wertheim stelt, of hebben zij wel gelijke rechten, maar moeten zij zich toch eerst aanpassen voordat zij echt gelijk zijn zoals Karacaer vermoedt. Er zijn verschillen tussen beide reacties. Wertheim en Karacaer maken deel uit van twee verschillende religieus etnische gemeenschappen en tussen beide reacties bestaat een tijdsverschil van ruim een eeuw. Toch zijn er ook grote overeenkomsten in hun reacties. Zij reageren op de ondergeschikte positie die anderen (Keuchenius en Hirsi Ali) hen, als joden respectievelijk moslims, in de Nederlandse samenleving toewijzen en zij gebruiken nieuwsbladen [De omschrijving ‘nieuwsbladen’ wordt gebruikt, in plaats van de gebruikelijkere omschrijvingen ‘dagbladen’ of ‘kranten’, omdat één van de onderzochte bladen een weekblad is] als platform om hun reacties te uiten, terwijl zij geen van beiden journalist zijn.

Het lijkt oude wijn in nieuwe zakken. Natuurlijk, de Nederlandse samenleving aan het eind van de 19e eeuw is niet de huidige Nederlandse samenleving, en joden en moslims behoren niet tot dezelfde religieus etnische gemeenschap. Maar vervang in een 19e-eeuws nieuwsbericht over joden de woorden joden en synagoge door moslims en moskee, pas het woordgebruik aan het huidige Nederlands aan en honderd jaar oud nieuws kan opnieuw als een 21e-eeuwse actualiteit worden uitgevent.

Waarom onderzoek ik de berichtgeving over juist deze groepen, joden en moslims en waarom ben ik geïnteresseerd in de beeldvorming over hen in nieuwsbladen? Wat beide groepen, ondanks grote verschillen, gemeen hebben is dat ze zich een plaats wilden en willen verwerven binnen de Nederlandse samenleving.

Er bestaan op het eerste gezicht veel overeenkomsten tussen de huidige berichtgeving over moslims en de toenmalige berichtgeving over joden, onder meer in de vaak negatieve en problematische boodschap die in de berichten doorklinkt. In hoeverre zijn deze overeenkomsten nog steeds zichtbaar als de berichtgeving systematisch over een langere periode wordt onderzocht? En in hoeverre bestaan er binnen beide perioden verschillen tussen nieuwsbladen in hun berichtgeving? Deze vragen vormden de aanleiding voor mijn onderzoek waarbij ik de berichtgeving over moslims tussen 1990 en 2013 en de berichtgeving over joden tussen 1890 en 1910 systematisch analyseer en vergelijk.

De manier waarop nieuwsbladen over moslims en over joden schrijven, wordt medebepaald door bewuste en onbewuste keuzes die gemaakt worden bij de productie van nieuws door o.a. journalisten, redacties en nieuwsorganisaties (Galtung en Ruge, 1965). Door de vergelijking kunnen deze keuzes en selecties aan het licht komen. Het gaat hier om keuzes die gemaakt zijn over de onderwerpen of personen die ter sprake komen, de mensen die aan het woord gelaten worden en de gebeurtenissen en gedragingen die aanleiding waren voor een bericht. Wanneer in de berichten over moslims steeds dezelfde onderwerpen en personen aan bod komen, dan is het aannemelijk dat bij de productie van het nieuws voortdurend dezelfde keuzes zijn gemaakt. Wanneer de berichtgeving tussen nieuwbladen niet veel verschilt dan zijn de keuzes over de inhoud van het bericht zeer waarschijnlijk niet exclusief door de journalisten, de redactie of elders binnen de nieuwsorganisatie, maar buiten het nieuwsblad gemaakt. Het nieuwsblad functioneert in een dergelijke situatie vooral als een doorgeefluik van het nieuws.

In de berichtgeving kan elke beschrijving van moslims en joden worden onderzocht, maar in mijn onderzoek gaat het om de beschrijvingen waarin het nieuwsblad niet alleen benadrukt waarover (een onderwerp, persoon of gebeurtenis) het de lezer informeert, maar daarbij ook aangeeft wat (een interpretatie) de lezer daarvan moet denken of vinden (Entman, 2007). Ik ben op zoek naar specifieke interpretaties van de positie van moslims en joden in de samenleving.

Deze interpretaties maken deel uit van een min of meer gesloten (samenhangend) geheel van interpretaties, resulterend in een beoordeling van nieuws, die ik in het vervolg omschrijf als normatieve referentiekaders. Deze referentiekaders beschouw ik als normatief omdat zij richtinggevend zijn voor de wijze waarop nieuwsbladen onderwerpen, personen en/of gebeurtenissen beschrijven. Wanneer ik deze referentiekaders vaak en met enige regelmaat in de berichtgeving aantref, dan spreek ik van beeldvorming. Beeldvorming die ook zichtbaar kan worden door de aan de referentiekaders gerelateerde aandacht voor bepaalde onderwerpen, personen en gebeurtenissen. Het zijn deze vaste patronen en kenmerken die ik in de berichtgeving over moslims en joden wil achterhalen.

Deze beeldvorming kan per nieuwsblad verschillen en na verloop van tijd veranderen. Berichtgeving en de beeldvorming die daaraan ten grondslag ligt, draagt in een belangrijke mate bij aan de meningsvorming van de lezer en de publieke opinie (Entman, 2007; McCombs, 2004; Lippmann, 1961). Het systematisch onderzoek naar beeldvorming in berichtgeving over moslims en joden kan ons inzicht verschaffen in de rol die media spelen bij het ontstaan of het verminderen van spanningen rond de positie van minderheidsgroepen in de samenleving.

Dit proefschrift is geen media-effect studie, dus dit onderzoek richt zich niet op de feitelijke beïnvloeding van de publieke opinie door berichtgeving.

Voor de inhoudelijke analyse heb ik voor beide perioden een selectie van berichten uit nieuwsbladen gemaakt. De berichten over moslims uit de periode 1990-2013 zijn afkomstig uit de vijf belangrijkste landelijke dagbladen met een betalend lezersbestand: NRC Handelsblad, Algemeen Dagblad, Trouw, De Volkskrant en De Telegraaf (Bakker & Scholten, 2014). Het gaat om een groot, maar niet volledig, bestand van digitaal beschikbare artikelen. De berichten over joden uit de periode 1890-1910 zijn afkomstig uit: Algemeen Handelsblad, De Telegraaf, De Tijd, De Standaard, Het Volk en Nieuw Israelietisch Weekblad.

Chomsky: US Policy Toward Russia Is Blocking Paths To De-Escalation In Ukraine

Russia’s war in Ukraine is producing an earthquake in international affairs. The war has raised new questions about national security across Europe and is shaking up energy geopolitics. In addition, the war seems to be creating new divisions between the Global North and the Global South while Russia and China strengthen their strategic relationship.

In the interview that follows, world-renowned scholar and leading dissident Noam Chomsky addresses some of the new developments taking place in the world system on account of Russia’s assault on Ukraine. Chomsky also ponders the question of whether Vladimir Putin can be prosecuted for war crimes in light of the mounting evidence that brings to mind the atrocities committed by the Nazis during World War II. Recent evidence also indicates that Ukrainian forces have also engaged in war crimes by killing captured Russian soldiers.

Chomsky, who is internationally recognized as one of the most important intellectuals alive, is the author of some 150 books and the recipient of scores of highly prestigious awards, including the Sydney Peace Prize and the Kyoto Prize (Japan’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize), and of dozens of honorary doctorate degrees from the world’s most renowned universities. Chomsky is Institute Professor Emeritus at MIT and currently Laureate Professor at the University of Arizona.

C. J. Polychroniou: The war in Ukraine has turned Russia into a pariah state throughout Europe and North America, but Moscow continues to receive support from many countries in the Global South. The strategic relationship between Russia and China seems to be getting stronger, although both countries had identified each other as major factors for maintaining order and stability in an “emerging polycentric world” long before Putin and Xi Jinping. In fact, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said following a recent meeting with his Chinese counterpart that the two countries are working together to advance a vision of a new world order, a new “democratic world order.” Is the new world order one that pits Global North and Global South countries against each other? And what do you make of the statement of Russia and China working together to promote a new “democratic world order?” To me, the idea of two autocratic states working together to promote democracy across the world sounds like a crude joke.

Noam Chomsky: The idea that Russia and China will be working together to promote a “democratic world order” is, of course, ludicrous. They will be doing so in much the way that the U.S. was laboring to “promote democracy” in Iraq, the goal of the invasion as President Bush announced when it became clear that the “single question” — will Saddam abandon his nuclear weapons program? — had been answered the wrong way. With rare exceptions, the intellectual class and even most scholarship leaped to attention and vigorously proclaimed the new doctrine, as I suppose is also the case today in Russia and China.

As U.S.-run polls showed, Americans enthralled by the “noble” goals belatedly proclaimed were even joined by some Iraqis: 1 percent of those polled. Four percent thought the U.S. invaded in order to help Iraqis. The rest concluded that if Iraq’s exports had been asparagus and pickles, and the center of global petroleum production was in the South Pacific, the U.S. wouldn’t have invaded.

I don’t pretend to have any expert knowledge, but from my own experience in past weeks with the Global South — press, many interviews and meetings, much personal discussion — it doesn’t seem to me quite accurate to say that it is supporting Moscow, except in the sense that Moscow is getting support from the Western powers that keep paying it for petroleum products and food (probably by now the source of Russia’s main export earnings).

My impression is that the Global South has sharply condemned the Russian invasion, but has asked: “What’s new?” The general reaction to President Biden’s harsh condemnation of Putin as a war criminal seems to be something like this: It takes one to know one. We agree that he is a war criminal, and as creatures of the Enlightenment, we adopt the Kantian principle of universality that is dismissed with contempt by the West, sometimes with angry charges of whataboutism.

It is, after all, not easy for people in the civilized world — increasingly, the Global South — to be impressed by the “moral outrage” of Western intellectuals who just a few years ago, when all the horrific facts were in, were enthusiastically applauding the success of the invasion of Iraq, spouting pieties about noble intentions that would have embarrassed the most abject apparatchik. And we can just imagine the reaction when they read the pious invocation of the Nuremberg judgment by the editors of The New York Times, who are just now coming to recognize that, “To initiate a war of aggression, therefore, is not only an international crime: it is the supreme international crime, differing only from other war crimes in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of the whole.” The accumulated evil includes the instigation of ethnic conflict that has torn apart not only Iraq but the whole region, the horrors of ISIS, and much more.

Not, of course, what the editors have in mind. The supreme international crimes that they have supported for 60 years somehow escaped the Nuremberg judgment.

While there is appreciation in the Global South for the fact that at long last Western intellectuals and the political class are coming to perceive that aggressors can commit hideous crimes, they seem to feel that it is perhaps a little late, and curiously skewed, as they know from ample experience. They are also able to perceive that Westerners consumed with moral outrage over the crimes of enemies are still able to maintain their usual silence while their own leaders carry out terrible crimes right now — in Afghanistan, Yemen, Palestine, Western Sahara, and all too many other places where they could act at once, and expeditiously, to mitigate or end these crimes.

Let’s turn to the “strategic relationship between Russia and China.” It does indeed seem to be strengthening, though it is not much of a partnership. The corrupt Russian kleptocracy can provide raw materials and advanced weapons to the economic system that Beijing is systematically establishing through mainland Asia, reaching also to Africa and the Middle East, and by now even to U.S. domains in Latin America. But not much more. Russia’s role in this highly unequal relationship is, I think, likely to diminish further, much as Europe’s international role is likely to diminish after Putin has handed Europe on a golden platter to the U.S.-run “Atlanticist” system, a gift of substantial significance, as we’ve discussed before.

Can China help end the war in Ukraine? If yes, what’s stopping Beijing from using its influence over Moscow for a peace agreement to be reached in Ukraine?

China could act to advance the prospects for a peaceful negotiated settlement in Ukraine. It seems that the Chinese leadership sees no advantage in doing so.

China’s “information system” appears to be pretty much conforming to the Russian propaganda line. But more generally, it doesn’t seem to diverge much from a fairly common stance in the Global South, illustrated graphically by the sanctions map. The states joining in sanctions against Russia are in the Anglosphere and Europe, as well as Japan, Taiwan and South Korea. The rest of the world condemns the invasion, but is mostly standing aloof.

This should not surprise us. It is nothing new. We recall well that the Iraq invasion had virtually no global support. Less familiar is the fact that the same was true of the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan after 9/11. A few weeks after the invasion, an international Gallup poll asked the question: “Once the identity of the [9/11] terrorists is known, should the American government launch a military attack on the country or countries where the terrorists are based or should the American government seek to extradite the terrorists to stand trial?”

The wording reflects the fact that their identity was not known. Even eight months later, in his first major press conference, FBI Director Robert Mueller could only affirm that al-Qaeda was suspected of the crime. If the poll had asked about actual U.S. policy, the very limited support would doubtless have been even lower.

World opinion overwhelmingly favored diplomatic-judicial measures over military action. Opposition to invasion was particularly strong in Latin America, which has a little experience with U.S. intervention.

The free press spared Americans knowledge of international opinion. It was therefore able to proclaim that “the opposition [to the U.S. invasion] was mostly limited to the people who are reflexively against the American use of power.”