De radeloze hoop van een fantast. De mythomanie van Boudewijn Büch

Gabriele d’Annunzio, de Italiaanse schrijver en oorlogsheld, is bij een groot publiek bekend geworden door de verfilming van L’Innocente, een novelle uit 1892 waarin de onschuldige baby uit de titel het slachtoffer wordt van een jaloerse, dominante vader. Als het aan de auteur zelf had gelegen, had hij zijn eeuwige roem vooral verworven met Il Vittoriale, de villa die in omvang en inrichting de megalomanie van zijn bewoner verraadt. Hij richtte het complex, dat tussen de cipressen door uitziet over het Gardameer, al bij zijn leven in als rariteitenkabinet in de vermomming van een museum, waartoe hij zelfs een compleet schip de berg op liet slepen. Kamer na kamer is gevuld met honderden voorwerpen, die slechts bij toeval bij elkaar lijken te staan.

Ondanks een beperkte lichamelijke aantrekkelijkheid en een chronisch slechte adem lag d’Annunzio, getuige zijn bijnaam de Sater, goed bij het andere geslacht. Dat kwam mooi uit, want zijn seksuele obsessie ging zo ver dat hij operatief enkele ribben liet verwijderen opdat hij zichzelf oraal kon bevredigen. Naar verluidt, want belangrijker dan de feiten was het beeld dat men van hem had.

De kwaliteit van beider werk even buiten beschouwing gelaten, liggen de parallellen tussen d’Annunzio en Boudewijn Büch voor de hand. Ook Büch dankte zijn bekendheid bij een groot publiek aan de verfilming van een boek waarin een kind overlijdt (De kleine blonde dood, 1985), ook hij vulde zijn huis, naast kostbare eerste drukken van haast onvindbare boeken, met opgezette dodo’s en kunst van uiteenlopende aard, en ook voor hem was de werkelijkheid ondergeschikt aan zijn fantasie.

En belangstelling voor het seksueel minder gangbare? Sla er zijn werk maar op na. In Een heel huis vol (2001) beschrijft hij een aantal Duitse geleerden die hun tijd en energie wijden aan de ‘casus van een dertienjarig meisje dat paarden steelt om met deze beesten de liefde te bedrijven (kleptomane hippo-zoöfilie)’ en citeert hij gretig uit het innige contact tussen ‘een ongetrouwd meisje’ en ‘een mannetjespapegaai’.

Boudewijn Maria Ignatius Buch werd op 14 december 1948 in Den Haag geboren. Hij groeide tussen zijn vijf broers op in Wassenaar, een jeugd die hem, ter illustratie van het adagium An unhappy childhood is a writer’s goldmine, tot een groot deel van zijn literaire oeuvre zou inspireren. Aanvankelijk vooral gedichten, eerst gepubliceerd in De Vonk, de schoolkrant van zijn lyceum in Leiden waarvan hij al snel hoofdredacteur werd, vervolgens ook in echte tijdschriften. Zijn officiële debuutbundel Nogal droevige liedjes voor de kleine Gijs (gewijd aan een jongen die op zijn dertiende sterft) verscheen in 1976, gevolgd door De taal als blauw (1977) en De sonnetten (1978).

Zijn gedichten werden, vriendelijk gezegd, gemengd ontvangen. C. Buddingh’ noemde Büch ‘een van ieder talent gespeend jongetje, dat verteerd wordt door eerzucht en, al is het maar in het Amsterdamse literaire café, ook voor een echte schrijver wil worden aangezien’. En Bernlef schreef na lezing van De sonnetten: ‘Misschien is die Büch wel helemaal een Nederlander, dacht ik nog even ter verklaring van zoveel baarlijke onzin. (..) Met poëzie, dat wil zeggen met het maken van gedichten met woorden, hebben deze rijmelarijen niets te maken.’

Eerzucht of inzicht, Büch maakte carrière: hij werd poëzierecensent van Hollands Diep, het clubblad van de grachtengordel dat maar een kort bestaan zou kennen. Begin jaren tachtig werkte hij mee aan een boekenprogramma van de VPRO-radio en niet lang daarna kreeg hij een eigen televisieprogramma bij de VARA, dat hem in staat stelde de vele oorden van zijn belangstelling te bezoeken. Met even grote bezetenheid als belezenheid maakte hij van literatuur een onderdeel van de vermaakindustrie. Zijn verschijning op de buis bezorgde hem de status van bekende Nederlander. Er was geen medium dat geen interview met hem wilde en de auteur bood ongeremd een weidse blik in zijn gekwelde bestaan: incest, een vader die zijn vrouw achterna zat met een bijl, een jaar in een krankzinnigeninrichting, bijna overleden aan een buikvliesontsteking, een school met paters, klasgenoten die hem in elkaar sloegen, een kind verloren aan een hersentumor: het was een opeenvolging van kommer en kwel, waarin hij feit en fictie niet altijd even goed gescheiden hield.

Waarvan twee kleine figuren … Oom Dirk over het verraad van Anne Frank

Oom Dirk had een missie. De wereld vertellen over het verraad van Anne Frank. In de ochtend van 4 augustus 1944 ontdekken agenten de onderduikers in het Achterhuis. Er bestaan allerlei theorieën over wie de onderduikers verraden heeft. Oom Dirk verwees al die verhalen naar de vuilnisbelt. Hij was getuige geweest van de inval. Dat in zijn versie de arrestatie in de avonduren plaatsvond, bewees alleen maar zijn gelijk. Hij had het immers gezien.

Oom Dirk, of Dove Dirk, was een van de vaste klanten van Koffiehuis de Hoek. Op zijn bakfiets bromde hij de stad door op zoek naar ijzerwaren. Op zijn woonboot op de Prinsengracht lag altijd een metershoge verzameling gevonden metalen voorwerpen.

Met handen en klanken kon oom Dirk zich prima redden. Al moest je soms even de tijd nemen als hij een van zijn stokpaardjes van achtergrondinformatie wilde voorzien.

Ooit had ik met oom Dirk beloofd dat ik zijn missie zou ondersteunen.

‘Harry heeft mijn papieren”, maakte hij me duidelijk.

Die papieren waren lange tijd zoek. Nu het koffiehuis dicht is, is er tijd om op te ruimen. Ook voor Laura en Harry.

‘We hebben de papieren van Dove Dirk gevonden’, appte Laura twee dagen geleden.

Oom Dirk is alweer een paar jaar geleden overleden. Vandaag los ik mijn belofte in.

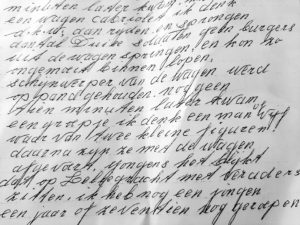

Hier de letterlijke tekst van het verslag van oom Dirk over het verraad van de familie Frank:

Jongens,

Hierbij deel ik jullie mede, j.l. las ik in beide kranten zowel de Telegraaf en Volkskrant van Woensdag 13 maart, het gaat over geval Anne Frank, en zijn familieleden, alles wat ik kranten las, laat ik jullie weten er kloppen alles niets van. Want ik heb alles meegemaakt, ik stond met de neus boven op.

Het gebeurd dan ook in oorlogstijd in 1944 het was dan ook in zomermaanden, laat we zeggen in maand Augustus, affijn om verder te gaan, zoals jullie zal weten, werd in Otto Frank pand wel eens ingebroken en insluipers binnen –geweest, zonder vermoeden over achterhuis dus goed onzichtbaar voor leek, want de gasten waren opuit om kolonialen waren, (ikzelf ben daar debet aan want ik daar nooit binnen geweest.)

Walking Stories

Lisa, a fragile Indonesian woman, walked along the paths of Saint Anthony’s park. Saint Anthony is a mental hospital. Lisa was dressed in red, yellow and blue; I was looking at a painting of Mondriaan, of which the colours could cheer someone up on a grey Dutch day. She had put on all her clothes and she carried the rest of her belongings in a grey garbagebag. She looked like she was being hunted, mumbling formulas to avert the evil or the devils. I could not understand her words, but she repeated them with the rustling of her garbage bag on the pebbles of the path.

Lisa, a fragile Indonesian woman, walked along the paths of Saint Anthony’s park. Saint Anthony is a mental hospital. Lisa was dressed in red, yellow and blue; I was looking at a painting of Mondriaan, of which the colours could cheer someone up on a grey Dutch day. She had put on all her clothes and she carried the rest of her belongings in a grey garbagebag. She looked like she was being hunted, mumbling formulas to avert the evil or the devils. I could not understand her words, but she repeated them with the rustling of her garbage bag on the pebbles of the path.

When she arrived at an intersection of two paths where low rose hips were blossoming, she stopped and went into the bushes. She lifted all her skirts and urinated; standing as a colourful flower amidst the green of the bushes and staring into the sky. A passer-by from the village where Saint Anthony’s has its headquarters would probably have pretended not to see her, knowing that Lisa was one of the ‘chronic mental patients’ of the wards. Or, urinating so openly in the park may be experienced as a ‘situational improperty’, but as many villagers told me: ‘They do odd things, but they cannot help it.’ The passer-by would not have known that Lisa was a ‘walking story’, that she had ritualised her walks in order to control the powers that lie beyond her control. Lisa was diagnosed with ‘schizophrenia’ and she suffered from delusions. When she had an acute psychosis, she needed medication to relieve her anxiety. Her personal story was considered as a symptom of her illness. That was, in a nutshell, the story of the psychiatrists of the mental hospital. Her own story was different. Lisa was the queen of the Indies and she had to have offspring to ensure that her dynasty would be preserved. She believed at that day that she was pregnant and that the magicians would come and would take away her unborn baby with a needle. To prevent the abortion, she had to take refuge in the park and carry all her belongings with her.

Judit Neurink ~ Geweld is nooit ver weg. Tien jaar berichten uit Irak

Judit Neurink vertrok in 2008 naar Irak om er met Nederlands geld een mediacentrum op te zetten om jonge journalisten te trainen en zo een bijdrage te leveren aan de prille democratie. Ze was er getuige van dat het land uiteenviel op basis van etniciteit en religie en dat de roep om een sterke leider toenam. Ze maakte de wederopbouw in Iraaks-Koerdistan mee, de opmars van ISIS en de ontvoering van en moord op duizenden Jezidi’s. Al zoekend naar de oorzaken en geweld in Irak na de val van Saddam Hoessein komt Neurink steeds uit bij de corruptie, die enorme gevolgen heeft voor het dagelijkse leven. Ook ISIS vormt nog steeds een groot gevaar. Na tien jaar in Irak te hebben gewoond en vijftien jaar erover schrijven verloor Judit Neurink de hoop dat het ooit nog goed zo komen. Ze woont nu in Athene, van waaruit ze ook weer bericht over Irak. (zie: https://juditneurink.eu/verzet-ten-tijde-van-corona/)

Geweld is nooit ver weg is een persoonlijk, intrigerend en fascinerend verslag van een bewogen gewelddadig decennium.

Judit Neurink doet verslag van de belangrijkste Iraakse steden: van de ‘opstandige stad’ Sulaymaniya in Koerdistan (Waar het verzet in het DNA zit), Bagdad (Hoofdstad van religie en corruptie), Najf (Het uitgewoonde huis van de sjiieten), naar Falluja (Hoe verzet omslaat in terrorisme), Mosul (De geest van ISIS), Basra (Stad van littekens en milities), Kirkuk (Het Jeruzalem van de Koerden), Sinjar (Toneel van een genocide), Tikrit (Saddams erfenis), Qaraqosh (Een snelweg als scheidslijn) en Erbil (Vertrouwen is niet te koop). Elke stad wordt uitgebreid beschreven met hun diepgewortelde conflicten en hoogte- en dieptepunten, hun culturele diversiteit en wat dat betekent voor haar inwoners.

Zoals Sulaymaniya, de opstandige stad in Iraaks-Koerdistan, waar de jeugd protesteerde tijdens de Arabische Lente, die vanaf maart 2011 in Irak plaatsvond. In Sulaymaniya was Neurink’s trainingscentrum gevestigd en kwamen er meer dan 70 projecten van de grond. Zo’n drieduizend mensen gingen de straat op. Het protest duurde twee maanden; er vielen doden en gewonden, waarna de opstand doodbloedde. Read more

Sasha Goldstein-Sabbah ~ Censorship And The Jews Of Baghdad: Reading Between The Lines In The Case Of E. Levy

Abstract

Abstract

This study examines how members of the Jewish community of Baghdad used foreign newspapers and journals to bring to light and gain international sympathy for issues concerning the community and its relationship with the Iraqi regime during the early years of the Iraqi state (roughly 1930–1950). As an

example of this phenomenon, the article examines a 1934 case in which authorities arrested E. Levy, author of a letter to the Manchester Guardian telling of the confiscation of foreign Jewish newspapers sent to Iraq and the opening of letters addressed to Jews by postal officials. Subsequent to his arrest, the community was not discouraged from writing in the foreign press. On the contrary, members of the Jewish community, both anonymously and by name, wrote in Jewish and non-Jewish foreign presses imploring the world to intercede on Levy’s behalf and to bring to light the situation afflicting the Jews of Baghdad. This article argues that foreign media was a successful tool for the Jewish community of Baghdad as an unofficial channel of negotiation for both communal and individual rights.

Introduction

In Iraq, the British Mandate lasted from 1920 until 1932. In the long history of the region, this short period of the Mandate is often considered “the Best of Times” for the majority of Iraq’s religious and ethnic minority groups.1 For the Jewish community of Iraq, this period is often considered the apex of social and cultural integration into general Iraqi society. The community was bolstered by Jewish socio-economic mobility due to an extensive (Jewish) community-sponsored education system and an increase in white-collar employment opportunities in both the civil service and with foreign firms. It was also a time of relative intellectual freedom with little government censorship and increased access to foreign print media.

However, the end of the Mandate in 1932 and the death of King Faisal in 1933 were met with concern in regard to the future of the relatively pluralist society which had developed and, as some would argue, foretold the beginning of the end for over two thousand years of Jewish life in Iraq. The 1930s represented a time of unease as the new state experienced political instability and unrest. Although not to be compared with the political turmoil and violence of the 1940s, for the Jewish community of Baghdad there was a perceivable difference in state policy in regard to the Jewish community after the Mandate ended. These changes included greater legislation in regard to education, unofficial quotas on the amount of Jews employed in the civil service, the official banning of Zionism (in 1935) as an ideology, greater antiJewish sentiment in the local press, and the censuring of both Jewish periodicals and post from abroad destined for Jews residing in Iraq. Although much attention has been given to the history of the Jewish community of Iraq in academic circles during the past decade, little work has specifically focused on how the Jewish community (both on a communal and on an individual level) perceived and reacted to these changes in the Iraqi state during this liminal period from the end of the Mandate of the 1920s to the chaos of the 1940s, and particularly on the question of competing loyalties between the Iraqi state and Jewish nationalism as embodied in the Zionist political movement.

Read more: https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/Goldstein_Sabbah_2016.pdf

Joe Shamash, Iraqi Jewish Cultural Extinction And Identity.

Joe Shamash was born in Baghdad,Iraq in 1948. He lived there with his parents, five brothers, and two sisters until they fled in 1957. Joe, who is still a citizen of Iraq, shares reflections on his identity and his current relationship to Iraq.

Joe Shamash. Iraqi Jewish Cultural Extinction and Identity.

JIMENA Oral History and Digital Experience Project, 2012

(C)Copyright, JIMENA INC

Produced by Sarah R. Levin

for more information please visit: www.jimenaexperience.org/iraq