Chomsky: Maintaining Class Inequality At Any Cost Is GOP’s Guiding Mission

The Republican Party has been steadily moving toward the extremely reactionary end of the scale over the past several decades. In some ways, Trump simply accelerated and finally cemented the GOP’s transition into an anti-democratic, proto-fascist political organization — although the Trump phenomenon is, in other ways, singular in political history, and its impact on U.S. politics and society will undoubtedly be felt for many years to come.

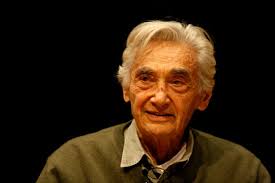

In the interview that follows, world-renowned scholar and public intellectual Noam Chomsky offers a tour-de-force analysis of the evolution of the U.S. political setting and the vital role that class warfare and repression have played in making corporate culture the dominant force, turning American society into a neoliberal dystopia. Chomsky also sheds light on why today’s GOP has turned U.S. politics into a culture war battle while pursuing policies that suppress social rights and strangle intellectual freedom, with Viktor Orbán’s “racist Christian nationalist proto-fascist government … hailed as the ideal for the future.” In addition, he assesses the political situation in connection with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act.

Chomsky is institute professor emeritus in the department of linguistics and philosophy at MIT and laureate professor of linguistics and Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in the Program in Environment and Social Justice at the University of Arizona. One of the world’s most-cited scholars and a public intellectual regarded by millions of people as a national and international treasure, Chomsky has published more than 150 books in linguistics, political and social thought, political economy, media studies, U.S. foreign policy and world affairs. His latest books are The Secrets of Words (with Andrea Moro; MIT Press, 2022); The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power (with Vijay Prashad; The New Press, 2022); and The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic and the Urgent Need for Social Change (with C.J. Polychroniou; Haymarket Books, 2021).

C.J. Polychroniou: Noam, the Republican Party has become an unabashedly anti-democratic political organization steering the U.S. toward authoritarianism. In fact, most GOP voters continue to support a political figure that sought to overturn a presidential election and seem to be enamored with Hungary’s strongman Viktor Orbán, who dismantled democracy in his own country. It is also of little surprise the way Republicans have responded to the FBI raid on Mar-a-Lago. The rule of law is of no consequence to them, yet conservatives charge that it is the Democrats who are moving the country toward authoritarianism. What’s shaping the character of the current Republican Party?

Noam Chomsky: What is unfolding before our eyes is a kind of classical tragedy, the grim conclusion foreordained, the march toward it seemingly inexorable. The origins are deep in the history of a society that has been free and bountiful for the privileged, awful for those who were in the way or cast aside.

A century ago, a stage was reached that has some similarity to today. In his classic study, The Fall of the House of Labor, labor historian David Montgomery writes that in the 1920s “corporate mastery of American life seemed secure.… Rationalization of business could then proceed with indispensable government support.” Inequality was soaring, along with corruption and greed. The vibrant labor movement had been crushed by Woodrow Wilson’s Red Scare, after decades of violent repression.

“Modern America had been created over its workers’ protests,” Montgomery continued, “even though every step in its formation had been influenced by the activities, organizations, and proposals that had sprung from working class life.” In the late 19th century, it seemed possible that the Knights of Labor, with its demand that those who work in the mills should own them, might link up with the radical farmers movement, the Populists, who were seeking a “cooperative commonwealth” that would free farmers from the tyranny of northeastern bankers and market managers. That could have led to a very different America. But it could not withstand state-corporate repression and violence.

A few years after the fall of the house of labor came the Great Depression. The labor movement revived and expanded, moving to large-scale industrial organization and militant actions. Crucially, there was a sympathetic administration, and a lively and often radical political environment. All of this laid the basis for the New Deal reforms that enormously improved American life and had repercussions in European social democracy.

The business world was split. Thomas Ferguson’s research shows that capital-intensive internationally oriented business accepted New Deal policies, while labor-intensive domestically oriented business was bitterly opposed. Their publications warned ominously of the “hazard facing industrialists” from labor action backed by “the newly realized political power of the masses,” topics explored in depth in Alex Carey’s Taking the Risks out of Democracy, which inaugurated the study of corporate propaganda.

As soon as the war ended, the business world launched a major assault on labor. It was impressive in scale, ranging from forced indoctrination sessions for the workforce even to taking over sports leagues. This was all part of the project of “selling free enterprise,” while the salesmen were happily gorging at the public trough where the hard and creative work of constructing the new high-tech economy was on the account of the friendly taxpayer.

Violent repression was no longer adequate to restoring the glory days of the ‘20s. More subtle means of indoctrination were devised, including “scientific methods of strike-breaking,” by now honed to a high art with the support of administrations since Reagan that barely pay attention to such labor laws as still exist.

The business campaign was expedited by the attack on civil liberties called “McCarthyism,” which led to expulsion of many of the most effective labor activists and organizers. Unions entered into a compact with capital to gain benefits for members (though not the public) in return for abandoning any significant role on the shop floor.

The regimented capitalism of the early postwar years has been called the “golden age of [state] capitalism,” with high and egalitarian growth. By the mid-‘60s popular activism was beginning to expose some of the long-concealed record of American history, and addressing some of its brutal legacy, again with the cooperation of a sympathetic administration.

By the early ‘70s, the established social order was tottering under the impact of the “Nixon shock” that undermined the postwar Bretton Wood system, stagflation, and not least, the growing threat of the popular movements that were civilizing the society. Elite concerns are well attested by major publications bracketing the mainstream spectrum of opinion.

At the left-liberal end, the liberal internationalists of the Trilateral Commission released their first publication, The Crisis of Democracy. The political flavor of the Commission is illustrated by the fact that the Carter administration was drawn largely from its ranks. The “Crisis” that concerned them was the activism of the ‘60s, which was mobilizing people to press their concerns in the political arena. These “special interests,” as they are called, were imposing too many pressures on the state, causing a crisis of democracy. The solution they recommended is more “moderation in democracy” by the special interests: minorities, women, the young, the old, workers, farmers, in short, the population, who are to be “spectators” not “participants,” in accord with liberal democratic theory (Walter Lippmann, Harold Lasswell, Reinhold Niebuhr, and other distinguished figures).

Unspoken is a crucial premise: the “special interests” are to be “put in their place,” as Lippmann advised, so that ample room is left for the “national interest” that is upheld by the “masters of mankind,” Adam Smith’s term for the business classes, who shape national policy so that their own interests are “most peculiarly attended to.” Smith’s words, which resonate loudly today. Read more

Howard Zinn, een sympathieke bemoeial

In het voorjaar van 1971 bereikten in de Verenigde Staten de protesten tegen de oorlog in Vietnam een hoogtepunt. Ruim zestig procent van de Amerikanen was tegen de oorlog, Washington werd bijna wekelijks overspoeld door massale demonstraties. Zo’n duizend Vietnamveteranen gooiden hun medailles over het hek bij het Capitool. Tijdens een van de demonstraties legden zo’n twintigduizend deelnemers het verkeer in Washington plat.

Een groepje gelijkgestemde vrienden dat te laat was om zich bij een demonstratie richting het Pentagon aan te sluiten, besloot toen maar op eigen houtje het verkeer op een kruispunt lam te leggen, nog onkundig van de massaal opgetrommelde politietroepen in de stad. Het groepje bestond uit een historicus, een docente aan de universiteit van Michigan, een Harvard- professor, taalkundige en filosoof Noam Chomsky, voormalig defensiemedewerker Daniel Ellsberg en historicus en activist Howard Zinn. Onder een wolk van traangas moest het groepje al gauw een zijstraat invluchten, waar het zich hergroepeerde en opnieuw een kruispunt blokkeerde, om vervolgens nog eens te worden verdreven. Het kat en muisspel duurde nog de hele middag.

Daniel Ellsberg, Howard Zinn, Noam Chomsky, Cindy Fredericks, and Marilyn Young at Mayday protests, May 3, 1971

Levensmotto

Het was geen uitzondering dat historicus Howard Zinn, professor in de politieke wetenschappen aan de universiteit van Boston, deelnam aan een demonstratie. ‘You can’t be neutral on a moving train’, was zijn levensmotto. In de jaren zestig was hij deelnemer aan tientallen demonstraties tegen segregatie, zette hij studieprogramma’s op voor kansarme zwarte studenten, en was hij actief in de burgerrechtenbeweging. Op 24 augustus was het honderd jaar geleden dat hij werd geboren.

Met een niet aflatende stroom boeken, artikelen, lezingen, commentaren en interviews, gaf hij decennia lang zijn mening over historische onderwerpen, maatschappelijke kwesties als burgerrechten, militarisme en oorlog, maar ook over zaken als onderwijs, recht, maatschappelijke onvrede, terrorisme en racisme. Hij volgde de Amerikaanse binnen- en buitenlandse politiek nauwlettend en kritisch. Voortdurend ageerde hij tegen onrecht in de samenleving. Zinn omschreef zichzelf als ‘something of an anarchist, something of a socialist, maybe a democratic socialist.’

Bombardementen

Zinn werd in 1922 geboren als kind van uit Oost-Europa afkomstige Joodse emigranten, woonachtig in de sloppenwijken van Brooklyn. Zijn ouders hadden het niet breed, in de crisisjaren dreef zijn vader een kleine snoepwinkel. In zijn jeugdjaren kon de leeshonger van de jonge Zinn maar moeilijk worden gestild, totdat zijn ouders hem een goedkope editie van het complete werk van Charles Dickens cadeau deden. Niet veel later stortte hij zich wonderlijk genoeg op het werk van Karl Marx. Op zijn zeventiende nam hij deel aan een antifascistische demonstratie op Times Square, georganiseerd door de Communist Party. Toen hij een jaar of twintig was vervulde hij allerlei baantjes, volgde een cursus creatief schrijven en kreeg uiteindelijk werk op een scheepswerf in New York. Door in het leger te gaan meende Zinn het fascisme effectief te kunnen bestrijden. Als tweede luitenant bij de Amerikaanse luchtmacht, nam hij tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog deel aan bombardementsvluchten vanuit Engeland op Berlijn en Tsjecho-Slowakije.

Napalm

Tegen het einde van de oorlog maakte hij deel uit van de eenheid die voor het eerst in de geschiedenis napalm inzette. Het Amerikaanse leger experimenteerde in de nadagen van de oorlog al met napalm en bij wijze van proef werden terugtrekkende Duitse troepen in het Franse stadje Royan met napalm bestookt. Na de oorlog kreeg Zinn te horen dat bij deze aanval op Duitse eenheden ruim duizend burgers om het leven waren gekomen. Hij deed zijn oorlogsmedailles in een envelop, schreef er Never Again op en keek er nooit meer naar om.

Na de oorlog bezocht hij Royan een aantal malen en deed er onderzoek naar de gevolgen van de bombardementen. Hij toonde aan dat deze strategisch van geen enkel nut waren geweest en dat de militaire autoriteiten hadden gelogen over het aantal burgerslachtoffers. De resultaten van zijn onderzoek publiceerde hij in The Politics of History (1970). Hierin bekritiseert hij scherp de geallieerde bombardementen op Dresden, Hamburg en Tokio tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, waarbij vooral burgerslachtoffers vielen, en het werpen van de atoombommen op Hiroshima en Nagasaki. Meerdere malen veroordeelde hij de nutteloze bombardementen van de VS op Bagdad tijdens de inval in Irak en de acties in Afghanistan waarbij honderden burgers het leven lieten, net als tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog door de VS vergoelijkt met termen als ‘collateral damage’ en ‘accidental’. Read more

Chomsky: Six Months Into War, Diplomatic Settlement in Ukraine Is Still Possible

The war in Ukraine continues unabated. There are no visible signs of a conclusion to this tragedy, although it’s hard to imagine the current situation remaining unchanged for much longer. The war has exposed dramatic weaknesses in Russia’s armed forces, while Ukrainian resistance has surprised even military experts. In the meantime, it is more than obvious that the U.S. is fighting a “proxy” war in Ukraine, as Noam Chomsky underlines in the exclusive interview for Truthout, thus making it extremely difficult for Russia’s military planners to make major advances.

From day one, Noam Chomsky established himself as one of the most important voices on the war in Ukraine. He condemned Russia’s invasion as a criminal aggression while analyzing the subtle political and historical context surrounding Putin’s decision to launch an attack on Russia’s neighbor. In the interview that follows, Chomsky reiterates his condemnation of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, suggests that the situation over peace talks inevitably recalls the “Afghan trap,” and talks about the exceptional form of censorship that is taking place in the U.S. through a systematic suppression of unpopular ideas over the war in Ukraine.

Chomsky is institute professor emeritus in the department of linguistics and philosophy at MIT and laureate professor of linguistics and Agnese Nelms Haury Chair in the Program in Environment and Social Justice at the University of Arizona. One of the world’s most-cited scholars and a public intellectual regarded by millions of people as a national and international treasure, Chomsky has published more than 150 books in linguistics, political and social thought, political economy, media studies, U.S. foreign policy and world affairs. His latest books are The Secrets of Words (with Andrea Moro; MIT Press, 2022); The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan, and the Fragility of U.S. Power (with Vijay Prashad; The New Press, 2022); and The Precipice: Neoliberalism, the Pandemic and the Urgent Need for Social Change (with C.J. Polychroniou; Haymarket Books, 2021).

C.J. Polychroniou: It’s been six months since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, yet there is no end to the war in sight. Putin’s strategy has backfired in a huge way, as it not only failed to take down Kyiv but also revived the western alliance while Finland and Sweden ended decades of neutrality by joining NATO. The war has also caused a massive humanitarian crisis, brought higher energy prices, and made Russia into a pariah state. From day one, you described the invasion as a criminal act of aggression and compared it to the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the Hitler-Stalin invasion of Poland, in spite of the fact that Russia felt threatened from NATO’s expansion to the east. I reckon that you still hold this view, but do you think that Putin would have had second thoughts about an invasion if he knew that this military adventure of his would end up in a prolonged war?

Noam Chomsky: Reading Putin’s mind has become a cottage industry, notable for the extreme confidence of those who interpret the scanty tea leaves. I have some guesses, but they are not based on better evidence than others have, so they have low credibility.

My guess is that Russian intelligence agreed with the announced U.S. government expectations that conquest of Kyiv and installation of a puppet government would be an easy task, not the debacle it turned out to be. I suppose that if Putin had had better information about the Ukrainian will and capacity to resist, and the incompetence of the Russian military, his plans would have been different. Perhaps the plans would have been what many informed analysts had expected, what Russia now seems to have turned to a Plan B: trying to establish firmer control over Crimea and the passage to Russia, and to take over the Donbas region.

Possibly, benefiting from better intelligence, Putin might have had the wisdom to respond seriously to the tentative initiatives of Macron for a negotiated settlement that would have avoided the war, and might have even proceeded to Europe-Russia accommodation along the lines of proposals by de Gaulle and Gorbachev. All we know is that the initiatives were dismissed with contempt, at great cost, not least to Russia. Instead, Putin launched a murderous war of aggression which, indeed, ranks with the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the Hitler-Stalin invasion of Poland.

That Russia felt threatened by NATO expansion to the East, in violation of firm and unambiguous promises to Gorbachev, has been stressed by virtually every high-level U.S. diplomat with any familiarity with Russia for 30 years, well before Putin. To take just one of a rich array of examples, in 2008 when he was ambassador to Russia and Bush II recklessly invited Ukraine to join NATO, current CIA director William Burns warned that “Ukrainian entry into NATO is the brightest of all redlines for the Russian elite (not just Putin).” He added that “I have yet to find anyone who views Ukraine in NATO as anything other than a direct challenge to Russian interests.” More generally, Burns called NATO expansion into Eastern Europe “premature at best, and needlessly provocative at worst.” And if the expansion reached Ukraine, Burns warned, “There could be no doubt that Putin would fight back hard.”

Burns was merely reiterating common understanding at the highest level of government, back to the early ‘90s. Bush II’s own Secretary of Defense Robert Gates recognized that “trying to bring Georgia and Ukraine into NATO was truly overreaching, … recklessly ignoring what the Russians considered their own vital national interests.” Read more

Liberal States Like California Are Also Failing To Make Progress On Climate

California has a well-established reputation as a national and global climate leader, but despite its remarkable successes in cutting emissions between 2006 and 2016, it has recently begun showing signs of having lost its way.

California is increasingly falling behind on its emissions reduction targets, and its existing policies have now been deemed insufficient to hit its 2030 target of reducing carbon emissions 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, according to new modeling from the climate policy think tank Energy Innovation.

“Compared to historical trends, California will need to more than triple the pace of emissions reductions to hit its 2030 target of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030,” the Energy Innovation report states.

The report is disappointing news, representing a weakening of the climate action that began with California’s passage of AB 32 in 2006. Otherwise known as the Global Warming Solutions Act, AB 32 was a landmark program in the struggle to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Up until 2006, the United States was the largest emitter of carbon dioxide emissions in the world, and California was the second highest state in terms of total greenhouse gas emissions.

Under AB 32, California was required to reduce statewide emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. It also required that California greenhouse gas emissions be reduced to 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050. The California Air Resources Board, established in 1967, became the agency responsible for the implementation of the law.

California met its goal to reach 1990 emissions levels by 2020 four years ahead of schedule. In 2016, lawmakers passed SB 32 as a follow up to AB 32. SB 32 requires the California Air Resources Board to ensure the state’s greenhouse gas emissions are reduced to 40 percent below the 1990 levels by 2030.

Surprisingly enough, however, California’s emission reduction efforts appeared to lose momentum after SB 32 was signed into law.

Unsurprisingly enough, an environmental group gave California a near failing grade on the climate crisis in 2021. This was the first time that California Environmental Voters, or EnviroVoters, gave a “D” mark to the state since the group began issuing its annual scorecard in 1973.

What explains California’s woeful progress on climate solutions?

For one, California hasn’t enacted any transformative climate bills over the past 4 years. Perhaps there is a connection between California’s recent inaction on the climate crisis and the fact that fossil fuel companies “spent four times as much as environmental advocacy groups and almost six times as much as clean energy firms on lobbying efforts in California between 2018 and 2021,” according to Capital & Main.

Indeed, California lawmakers are failing to advance bills that include deep decarbonization initiatives. When a new bill AB 1395, a net-zero bill co-authored by Assembly Members Al Muratsuchi and Cristina Garcia, was introduced on the last day of last year’s legislative session, it was resoundingly defeated. It would have codified in law the state’s pledge to achieve carbon neutrality as soon as possible and by no later than 2045. It was opposed by the oil and gas sector, the agricultural industry and business groups. Read more

The Inflation Reduction Act Should Be Just The Beginning

Without more direct intervention on the part of the public sector in combatting the climate crisis, what IRA will produce is a green capitalist industry with profit-making as the overriding concern.

The Schumer-Manchin reconciliation bill known as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which is expected to become law after it cleared the Senate on a party line vote and key House Democrats have already signaled that they will vote for it when it moves to the lower chamber of Congress, aims to boost the economy and fight the climate crisis. It will also extend the Affordable Care Act subsidies through 2024, lower a handful of prescription drug prices (for those who are on Medicare), boost IRS enforcement, and require large corporations to pay at least 15 percent of their total profits in taxes.

This reconciliation bill is a slim-down version of the Build Back Better Act. It’s a compromise, and therefore hardly adequate to address the needs of American working-class people and confront the climate challenge. In fact, to call IRA a “historic piece of legislation” is an overstatement. But it is a step in the right direction, especially for a country where corporations and big business run roughshod over the common good.

First, forget inflation, in spite of the title that the bill carries. IRA would have no impact on inflation in 2022 and negligible effect in 2023, according to a report from the Congressional Budget Office.

A major piece of the bill focuses on healthcare. There are some positive aspects in it, but, again, hardly enough to make anything beyond a moderate impact on the well-being of average Americans. It extends Affordable Care Act subsidies for the next three years, lowers somewhat healthcare cost for low-income families, and permits Medicare for the first time in its history to negotiate prices for some prescription drugs. Prescription drugs cost much more in the U.S. (in some instances by as much as over 400%, as in the case of Humira, which is used to treat many inflammatory conditions in adults) than in other developed countries, and the U.S. remains the only country in the developed world without a universal healthcare system.

As Bernie Sanders charged, “this bill does nothing to address the systemic dysfunctionality of the American health care system.”

IRA also seeks to address tax fairness and reduce inequality. It claims that it will create a more equitable United States by compelling corporations with more than $1 billion in profits to pay a 15 percent minimum tax. Conservative democratic senator Kyrsten Sinema, who always sides with the rich and the corporations, first forced the removal of the carried interest tax provision from the bill and then delivered a gift to private equity firms by protecting them from the minimum tax aimed at large corporations.

Forcing corporations making more than $1 billion in profits pay a minimum corporate tax rate of 15 percent can hardly be considered a major step forward in addressing the issue of inequality. However, the corporate minimum tax in the Inflation Reduction Act has quite different rules from the global minimum tax. It is possible, but not likely, that corporations could end up facing both taxes, and that would indeed be a useful start towards tackling extreme inequality.

Energy and climate are what the Inflation Reduction Act is mostly all about. IRA would raise approximately $739 billion over 10 years and spend $433 billion on new investments over a decade, resulting in an overall deficit reduction of roughly $300 billion. The big winners from this deal are indeed energy and climate as IRA pledges $369 billion towards energy security and clean energy. The climate and environmental measures included in the bill are expected to reduce carbon emissions by 40 percent below 2005 levels by 2030.

So, let’s take a brief look at the energy and climate provisions included in the act. Read more

Let’s Acknowledge Inflation Reduction Act’s Significance — And Its Inadequacy

The Schumer-Manchin reconciliation bill, called the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), is a massive piece of legislation that aims to boost the economy and fight the climate crisis. It passed the Senate on Sunday, and is expected to quickly pass the House. On the economic front, the bill will reduce the deficit, close critical tax loopholes exploited by big corporations, and create millions of new jobs over a decade through the implementation of numerous energy and climate measures. The IRA is the most important climate bill in U.S. history. Nonetheless, it is also a bill full of defects, and parts of it will actually make the climate crisis worse, says Robert Pollin, one of the world’s leading progressive economists, in this exclusive interview for Truthout. Pollin is distinguished professor of economics and codirector of the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. He is the author of numerous books, including Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet(coauthored with Noam Chomsky), as well as of scores of green economy transition programs for U.S. states (including California, Maine, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia) and different countries.

C.J. Polychroniou: The IRA is far less ambitious than what was originally envisioned in the Build Back Better Act, but still regarded as a step in the right direction. If it becomes law, it will address some outstanding concerns about climate, health care and corporate taxes. The agreement would raise approximately $739 billion over 10 years and spend $433 billion over a decade, which means it will reduce the deficit. However, the big winners from this deal will be climate and energy as the IRA pledges $369 billion toward energy security and clean energy. The bill’s supporters in Congress state that the climate and environmental measures included in the bill will reduce carbon emissions by 40 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. So, let’s start with the climate details in the act. First, is the sum of $369 billion spent over a decade big enough to address an existential threat like global warming? In fact, will the climate and energy provisions incorporated into the bill, which include the requirement that the Interior Department offers at least 2 million acres a year for offshore oil and gas leases, even achieve the designated emissions-reduction target by 2030?

Robert Pollin: The Inflation Reduction Act is the most significant piece of climate legislation ever enacted by the U.S. government. It is also, in itself, not close to sufficient, to move the U.S., much less the global economy, onto a viable climate stabilization path. We need to be 100 percent clear on both points. This is the only way that we can, at once, take maximum advantage of the major resources the IRA will provide to fight the climate emergency while also recognizing the huge areas where the bill accomplishes little to nothing as well as where it actually contributes to worsening the crisis.

First, on the positive side, it is a big deal for the federal government to provide roughly $400 billion over 10 years to fight climate change. To put this into perspective, this is exactly $400 billion more than what had been on the table only three weeks ago. This level of federal support will also encourage at least another $600 billion in private spending. The public funds will leverage private investment through, among other specific programs, tax credits for clean energy investments, consumer rebates for electric vehicle and heat pump purchases, loan guarantees that lower risks to banks for clean energy investments, and a national Green Bank underwritten by the federal government. This would bring total public plus private clean energy spending from the IRA to roughly $1 trillion over 10 years, or about $100 billion per year.

This is a huge sum of money, but also not nearly enough. Keep in mind that $100 billion equals about 0.4 percent of current overall economic activity, i.e., GDP. By my own estimates and those by others, for the U.S. to reach the emission reduction targets set out by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) — i.e., a 50 percent CO2 emissions cut by 2030 and zero emissions by 2050 — will require about $400 billion in today’s economy and an average of $600 billion per year between now and 2050. So the total amount of public and private clean energy spending generated by the IRA would deliver, at best, about 25 percent of the necessary funding level. Again, 25 percent is way better than 0 percent. But it is also way worse than 100 percent.

I want to emphasize that this is a best-case scenario. The main reason is because of what Sen. Joe Manchin extracted from his fellow Democrats in exchange for his endorsement. Manchin agreed to support the IRA only if, in return, his fellow Democrats would support the construction of the 300-mile Mountain Valley natural gas pipeline that would run through West Virginia as well as Virginia.

The pipeline will likely create major environmental damage, including the contamination of rural streams and land erosion. But still worse is the obvious fact that building a new natural gas pipeline only makes economic sense if we are still burning natural gas to produce energy for the next 50 years or so. This is despite the fact that burning natural gas — along with burning oil and coal — to produce energy is, by far, the main cause of climate change. Support for the Mountain Valley pipeline in West Virginia is, unfortunately, fully consistent with the point you mentioned, that the IRA mandates the expansion of oil and gas exploration leases on federal land and water.

How can we possibly reconcile a supposedly transformative piece of climate legislation with building new natural gas pipelines? The only conceivable way to get there is to also support massive-scale deployment of carbon capture technology as a major component of the overall U.S. emissions-reduction program. Carbon capture technologies aim to remove emitted carbon from the atmosphere and transport it, usually through pipelines, to subsurface geological formations, where it would be stored permanently. To date, the general class of carbon capture technologies have not been proven to work at a commercial scale, despite decades of efforts to accomplish this. After all, carbon capture would be the savior for oil, coal and natural gas industries if the technology could be made to work commercially at scale. A major problem with most carbon capture technologies is the prospect for carbon leakages that result through flawed transportation and storage systems. These dangers will only increase to the extent that carbon capture does end up becoming commercialized and operates under an incentive structure in which maintaining safety standards cuts into corporate profits.

Matters become still worse to the extent that the IRA channels big-time funding into carbon capture, as could easily happen. Several of the major programs within the overall bill do not have fully specified mandates, including the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, the Clean Energy Investment and Production Tax Credits, and the Clean Energy Loan Guarantees. When push comes to shove — and, in particular, with oil companies and the likes of Senator Manchin doing the pushing and shoving — big chunks of funding through these programs are likely to be channeled into carbon capture. This would then mean less money for solar and wind — where the money needs to go. Read more