The Ethnic Violence In Manipur, India, Explained

The ethnoreligious violence in the Indian state of Manipur between Meiteis and Kukis has been ongoing since May, but it was only in July 2023 when a video went viral in India showing two women being paraded naked that the world began to pay attention to the situation in earnest. One of the women was reportedly sexually assaulted after the conclusion of the video. Calls for accountability came from all quarters, including the Indian Supreme Court, and even Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), was forced to break his conspicuous silence on the conflict in the northeastern state.

The majority of the conflict has been dominated by Meitei mobs, who are mostly Hindus, attacking the predominantly Christan Kukis. The Meiteis have been looting and burning down churches and homes and murdering people, though numerous attacks by the Kukis have also occurred. More than 200 people have been killed as of September 20, with about two-thirds being Kuki and one-third being Meitei. However, property damage is extensive, and tens of thousands of people have been displaced.

“How can we coexist with people who are constantly attacking us and want us to be annihilated… All we want from the government now is a separate administration,” one Kuki farmer said to the New Humanitarian.

In some ways, understanding the violence in Manipur is simple: the Meiteis, who are in the majority, are attacking the minority Kuki community under the auspices of the newly ensconced Hindu right-wing government led by the Bharatiya Janata Party at the state level. It is a playbook that goes back at least two decades to the BJP and allied right-wing Hindu organizations’ 2002 anti-Muslim pogroms in Gujarat.

The BJP and its affiliated paramilitary groups like the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) have sought to establish themselves in Manipur as in many other parts of the country. In 2017, the BJP won enough seats in state elections to displace the then-ruling Congress Party through a minority government for the first time. In 2022, it won enough seats to form a majority government at the state level. The emergence of Hinduized communal (sectarian) politics at the state level has led to ethnoreligious violence along with an internet blackout in Manipur.

But as with so much else in India’s ethnically and politically fragmented northeast, the devil is in the details. The northeast is connected to the rest of the Indian subcontinent through a narrow stretch of land referred to as the “Chicken’s Neck.” It is where the country narrows to less than 15 miles between Bangladesh and Nepal. Manipur is one of eight northeastern states and can be broken down into two major areas defined by geography: the hills and the Imphal Valley. In Manipur, the Kukis live predominantly in the hills while the Meiteis primarily occupy the valley. The other communities of the state—the Nagas, for example, another Scheduled Tribe (ST) (the government designation for Indigenous people) who also live in the hills, and the Pangals, who are Muslim Meiteis—have largely been sitting out this conflict.

Further complicating matters, the Kukis can be broken down into individual tribes, viewed as “new” or “old” Kukis depending on when they migrated to Manipur, and are considered as part of a larger agglomeration of related peoples outside of Manipur. The latter are known as the Zo or the Kuki-Zo communities of Myanmar, India, and Bangladesh.

The trigger for the recent conflict was a Manipuri court decision in March that would have paved the road for the Meiteis to also secure ST status, which they don’t currently have, and would have conferred several benefits under India’s affirmative action system. The Kukis, already economically, demographically, and—consequently—politically weaker in the state fear the added privileges that the Meiteis would get if the latter are designated a Scheduled Tribe.

In particular, they have been worried about a land grab by the Meiteis in the hills, which ST status for Meiteis would permit as under the current law, “non-tribals, including the Meiteis, cannot purchase land in the hills,” according to Outlook. The Kukis have also been protesting the fact that the Meiteis already benefit from other affirmative action designations, and adding this new boost would provide them complete dominance in a state that they already largely control: two-thirds of the state legislature’s seats come from the Meitei-dominated Imphal Valley, with only one-third from the hills. Read more

The Perilous Path From Western Domination To De-Dollarization

Justin P. Podur – Photo: York University

Two interesting things happened at the BRICS summit in South Africa in August. Several new members were invited to join BRICS in 2024: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. And, at Brazil’s urging, a commission was established to study the possibility of a new currency to replace the dollar in international trade. Currency swap agreements will continue to be the way the process moves forward in the short term, though, because the dollar cannot be replaced in a rush.

To escape the shackles of dollarization, Global South countries have a perilous path to walk. The major problems, as described by political economists Michael Hudson and Radhika Desai, are as follows: Global South countries are saddled with immense debts in dollars, and Western corporations claim ownership over their resources. The international legal structure favors the West, finding in favor of American corporations and vulture funds. The U.S.-run covert network continues to have the ability to foment wars and coups against those who defy Western rules—including financial ones. These problems now confront most countries of the world.

Thus far, most of the world is not polarized. Very few countries (mostly in Europe) are unconditional supporters of the U.S.-led West. On the other side, only a handful of states (e.g. Russia, China, Iran) dare to categorically refuse when the West makes demands.

Everyone else—where the future of the global economy will play out—is in-between. Will they find a way out of these traps?

Argentina’s Politicized Debt

For about 200 years, Argentina has been the site of first British, and then U.S. experiments in debt-driven subjugation. Each time a developmentalist government came to power and tried to get the country out of a crisis, it would be followed by a right-wing government that would plunge the country back in.

Among the in-between countries, Argentina has a special role. The country is on the list of the new invitees to BRICS. Its finances are in disarray, and its leading presidential candidate, who takes economic advice from his four dogs, wants to close most of the government down and use the U.S. dollar as the currency. Like many right-wing Western politicians, from Berlusconi and Sarkozy to Trump and Bolsonaro, Milei’s electoral brand is damaged neither by clown antics nor by infeasible economic plans.

And infeasible they are. The Economist notes that “Milei promises cuts worth 15 [percent]… of GDP, to a public sector that accounts for 38 [percent]… of GDP, but struggles to outline where they will come from.”

Nor does he know

“how… Milei’s government would find the $40 [billion] his team thinks is necessary to make the switch to dollars. Currently, Argentina cannot even repay the [International Monetary Fund (IMF)]… to which it owes $44 billion. Having run out of American currency, the central bank is instead burning through yuan borrowed from China… Milei has suggested selling state-owned firms and government debt in an offshore fund to raise the necessary capital. It is hard to imagine there will be many buyers.”

Argentina’s fate has been controlled by imperial debt since 1824 when the British Empire’s bank (Barings—whose Lord Cromer used financial methods to take over Egypt, among other notable operations) first advanced a loan of one million pounds to newly independent Argentina. This was less than 20 years after the British landed forces to try unsuccessfully to colonize Argentina. They ultimately found the financial weapon more effective. The first of nine defaults followed in 1827. The latest was in 2020 (the Economist is advocating a tenth).

In the 20th century, Argentina alternated between elected governments and military dictatorships and switched between developmentalist and neoliberal economic approaches. In the neoliberal periods, Argentina was the site of innovation—new experiments in plundering a country were invented. Among these was what Esteban Almiron outlined as the “financial bicycle” made possible by the peg of the peso to the U.S. dollar:

“When billionaire speculators were allowed to exchange Argentine pesos for unlimited amounts of dollars, benefiting from [high-interest]… rates in pesos, it was the state that had to borrow those dollars from [U.S.]… private banks or from the IMF and pay interests on them. Once exchanged, the dollars obtained by the speculators were moved out of the country, leaving the debt to the state.” Read more

Endgame For Syriza? The Unbearable Lightness Of The Greek Left

C.J. Polychroniou

Perhaps those who voted for Kasselakis are unfamiliar with U.S. politics and the true color of the Democratic Party, but it is a vision that undoubtedly sends shivers down the spine of the members of the old guard.

The Third Way is a political term that gained currency in the late 1970s and early 1980s and is associated with the New Labour administration of Tony Blair, who served as UK’s prime minister from 1997 to 2007, but also with those of Bill Clinton in the US (1993-2001) and Gerhard Schroder in Germany (1998-2005), respectively. The term itself was developed by British sociologist Anthony Giddens and denotes a distinct political ideology that argues in favor of so-called “centrist” politics.

Essentially, Third Way proposals seek to reconcile right-wing and left-wing policies. More specifically, the “Third Way” aims to integrate center-right economic policies and center-left social policies. As such, the “Third Way” is really nothing short of a political stratagem whose underlying goal is to maintain the hegemony of capitalism by making the system sensitive to cultural and social sensibilities. Disregarding the left flank, embracing the “catch-all” thesis, and loosening the influence of labor in the economy and society at large while promoting at the same time the politics of multiculturalism define the politics and strategy of social-democratic parties that became part of the “Third Way” movement.

Indeed, by the late 1990s, virtually all the social-democratic parties in advanced capitalist societies had fallen prey to the fatal attraction of the Third Way mentality while the traditional values and beliefs of the old Left joined the dustbin of history. The only country in the western world with a radical leftwing party that did not fight for power on the ground laid by the Third Way was Greece.

Until very recently, that is.

Part of the explanation for the “delay” of Greek leftwing parties in adopting the approach of the “Third Way” is that social democracy was never established in Greece. Throughout the 20th century, the bulk of the country’s left had aligned with a Marxist-Leninist Communist Party, named KKE, but a major split occurred in 1968 following the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. A big group broke from the KKE, forming KKE Interior, which eventually came to identify itself with Eurocommunism, a political movement that flourished in the late 1970s in several western European communist parties and sought to introduce socialism beyond the political and ideological orbit of Soviet communism.

The Coalition of the Radical Left (Syriza) traces its roots to the KKE Interior, although Eurocommunism disappeared as an international current shortly after its birth and, for all practical intents and purposes, the Syriza party that rose to power in Greece in 2015 was a political organization that had no discernible ideological traits whatsoever other than an expressed aversion to the fiscal austerity measures that had been imposed on the country by its international creditors — namely, the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund – as a condition to the bailout deals that had been crafted in 2010 and 2012, respectively.

However, while in power, Syriza experienced a huge metamorphosis. The dilemma of choosing between resistance and capitulation was resolved in favor of the latter. Syriza had promised voters it would ditch austerity and in fact rip to pieces the bailout memorandum. In turn, it not only continued to enforce the same austerity program that had been implemented by the previous Greek governments but ended up signing a third bailout memorandum..

Moreover, even before coming to power, Syriza had initiated a series of moves that aimed to reshape the party’s political profile in congruence with the trends observed in those western social democratic parties that had adopted the “Third Way” proposals. The process of Syriza’s transformation into a mainstream party continued unabated both when the “left” was in power (from 2015-2019) and back in opposition (2019-2023). Yet, while it was abundantly clear that the party, under the leadership of Alexis Tsipras and his inner team, was bent on abandoning its tradition of radical politics and that a prominent left faction inside Syriza was too weak to halt that process, it wasn’t at all clear where the party’s base stood.

The answer to that mystery was revealed during the leadership election that was held just this past Sunday when party members elected a gay, liberal, former Goldman Sachs trader, shipping investor, and political neophyte Stefanos Kasselakis to head the once radical left-wing Syriza party.

Tsipras had stepped down as Syriza chief following his party’s humiliating defeat in the June 2023 general elections. Given the party’s dwindling public support, Tsipras’ resignation was inevitable, but the question why Syriza members (though it should be said that some 40,000 were registered as members on the spot) decided to place the future of the party into the hands of someone who was light on policy and heavy on social media marketing during his campaign speaks volumes about the political processes that had been unleashed by Tsipras and his inner circle over the past 9 years or so.

Kasselakis, with no experience in politics and no leftist credentials, but with the blessing of Tsipras himself and his closest associates, beat former Minister of Labor Effi Achtsioglou in a runoff election, sending shockwaves throughout the Greek left. Read more

How Can We Understand The Passage Of Time?

Photo: en.wiki.eng

Recent developments in the study of human prehistory hold clues about our times, our world, and ourselves.

We can all agree that most people want to know about their origins—spanning from their family and ancestral history and even, occasionally, deeper into the evolutionary story.

Lately, this desire has become more palpable in society at large and even taken on urgent tones as we drift away from the lifestyle patterns and traditions that humans relied on for millions of years toward a technoculture that is highly addictive, and hard to understand or break away from.

But the desire to know the deep past doesn’t translate so easily into understanding, especially since the information we encounter is necessarily filtered by our own sociohistorical context. One of the biggest obstacles to gaining a true understanding of the unfolding of humanity’s past is the way that modern societies foster a superficial understanding of the passage of time.

To delve deeply into human prehistory requires adopting a different kind of chronological stance than most of us are accustomed to—not just a longer period of time, but also a sense of evolution infused by the operating rules of biology and its externalities, such as technology and culture. But exploring the past enables us to observe long-term evolutionary trends that are also pertinent in today’s world, elucidating that novel technological behaviors that our ancestors adopted and transformed into culture were not necessarily better, nor more sustainable over time.

Nature is indifferent to the recency of things: whatever promotes our survival is passed on and proliferated through future generations. This Darwinian axiom includes not only anatomical traits, but also cultural norms and technologies.

Shared culture and technologies give people the ongoing sensation of the synchronization of time with each other. The museums and historical sites we visit, as well as the books and documentaries on the human story, overwhelmingly present the past to their audiences through simultaneous or synchronized stages that follow a kind of metric system of conformity in importance. Human events are charted along the direction of either progress or failure.

The archeological record shows us, however, that even though human evolution appears to have taken place as a series of sequential stages advancing our species toward “progress,” in fact, there is no inherent hierarchy to these processes of development.

This takes a while to sink in, especially if you’ve been educated within a cultural framework that explains prehistory as a linear and codependent set of chronological milestones, whose successive stages may be understood by historically elaborated logical systems of cause and effect. It takes an intellectual leap to reject such hierarchical constructions of prehistory and to perceive the past as a diachronous system of nonsynchronous events closely tied to ecological and biological phenomena.

But this endeavor is well worth the effort if it allows people to recognize and make use of the lessons that can be learned from the past.

If we can pinpoint the time, place, and circumstances under which specific technological or social behaviors were adopted by hominins and then follow their evolution through time, then we can more easily understand not only why they were selected in the first place, but also how they evolved and even what their links with the modern human condition may be.

Taking on this approach can help us understand how the reproductive success of our genus, Homo, eventually led up to the emergence of our own species, sapiens, through a complex process that caused some traits to disappear or be replaced, while others were transformed or perpetuated into defining human traits.

While new discoveries are popularizing the exciting new findings dating as far back as the Middle Paleolithic, the public is typically presented with a compressed prehistory that starts at the end of the last ice age some 12,000 years ago. This is understandable, since the more recent archeological register consists of objects and buildings that are in many ways analogous to our own patterns of living. Ignoring the more distant phases of the shared human past, however, has a wider effect of converting our interpretations of prehistory into a sort of timeless mass, almost totally lacking in chronological and even geographical context. Read more

Artificial Intelligence: Profit Versus Freedom

Richard D. Wolff

Artificial Intelligence (AI) presents a profit opportunity for capitalists, but it presents a crucial choice for the working class. Because the working class is the majority, that crucial choice confronts society as a whole. It is the same profit opportunity/social choice that was presented by the introduction of robotics, computers, and indeed by most technological advances throughout capitalism’s history. In capitalism, employers decide when, where, and how to install new technologies; employees do not. Employers’ decisions are driven chiefly by whether and how new technologies affect their profits.

If new technologies enable employers to profitably replace paid workers with machines, they will implement the change. Employers have little or no responsibility to the displaced workers, their families, neighborhoods, communities, or governments for the many consequences of jobs lost. If the cost to society of joblessness is 100 whereas the gain to employers’ profits is 50, the new technology is implemented. Because the employers’ gain governs the decision, the new technology is introduced, no matter how small that gain is relative to society’s loss. That is how capitalism has always functioned.

A simple arithmetic example can illustrate the key point. Suppose AI doubles some employees’ productivity. During the same work time, they produce twice as much as before the use of AI. Employers who use AI will then fire half of their employees. Such employers will then receive the same output from the remaining 50 percent of their employees as before the introduction of AI. To keep our example simple, let’s assume those employers then sell that same output for the same price as before. Their resulting revenues will then likewise be the same. The use of AI will save the employers 50 percent of their former total wage bills (less the cost of implementing AI) and those savings will be kept by employers as added profit for them. That added profit was an effective incentive for the employer to implement AI.

If we imagine for a moment that the employees had the power that capitalism confers exclusively on employers, they would choose to use AI in an altogether different way. They would use AI, fire no one, but instead cut all employees’ working days by 50 percent while keeping their wages the same. Once again keeping our example simple, this would result in the same output as before the use of AI, and the same price for the goods or services and revenue inflow would follow. The profit margin would remain the same after the use of AI as before (minus the cost of implementing the technology). The 50 percent of employees’ previous workdays that are now available for their leisure would be the benefit they accrue. That leisure—freedom from work—is their incentive to use AI differently from how employers did.

One way of using AI yields added profits for a few, while the other way yields added leisure/freedom to many. Capitalism rewards and thus encourages the employers’ way. Democracy points the other way. The technology itself is ambivalent. It can be used either way.

Thus, it is simply false to write or say—as so many do these days—that AI threatens millions of jobs or jobholders. Technology is not doing that. Rather the capitalist system organizes enterprises into employers versus employees and thereby uses technological progress to increase profit, not employees’ free time.

Throughout history, enthusiasts celebrated most major technological advances because of their “labor-saving” qualities. Introducing new technologies would deliver less work, less drudgery, and less demeaning labor. The implication was that “we”—all people—would benefit. Of course, capitalists’ added profits from technical advances no doubt brought them more leisure. However, the added leisure new technologies made possible for the employee majority was mostly denied to them. Capitalism—the profit-driven system—caused that denial. Read more

Is This The End Of French Neo-Colonialism In Africa?

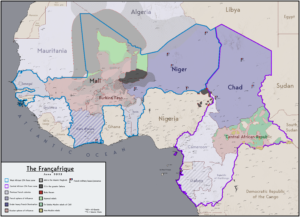

Françafrique – en.wikipedia.org

In Bamako, Mali, on September 16, the governments of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger created the Alliance of Sahel States (AES). On X, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, Colonel Assimi Goïta, the head of the transitional government of Mali, wrote that the Liptako-Gourma Charter which created the AES would establish “an architecture of collective defense and mutual assistance for the benefit of our populations.” The hunger for such regional cooperation goes back to the period when France ended its colonial rule. Between 1958 and 1963, Ghana and Guinea were part of the Union of African States, which was to have been the seed for wider pan-African unity. Mali was a member as well between 1961 and 1963.

But, more recently, these three countries—and others in the Sahel region such as Niger—have struggled with common problems, such as the downward sweep of radical Islamic forces unleashed by the 2011 North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) war on Libya. The anger against the French has been so intense that it has provoked at least seven coups in Africa (two in Burkina Faso, two in Mali, one in Guinea, one in Niger, and one in Gabon) and unleashed mass demonstrations from Algeria to the Congo and most recently in Benin. The depth of frustration with France is such that its troops have been ejected from the Sahel, Mali demoted French from its official language status, and France’s ambassador in Niger (Sylvain Itté) was effectively held “hostage”—as French President Emmanuel Macron said—by people deeply upset by French behavior in the region.

Philippe Toyo Noudjenoume, the President of the West Africa Peoples’ Organization, explained the basis of this cascading anti-French sentiment in the region. French colonialism, he said, “has remained in place since 1960.” France holds the revenues of its former colonies in the Banque de France in Paris. The French policy—known as Françafrique—included the presence of French military bases from Djibouti to Senegal, from Côte d’Ivoire to Gabon. “Of all the former colonial powers in Africa,” Noudjenoume told us, “it is France that has intervened militarily at least sixty times to overthrow governments, such as [that of] Modibo Keïta in Mali (1968), or assassinate patriotic leaders, such as Félix-Roland Moumié (1960) and Ernest Ouandié (1971) in Cameroon, Sylvanus Olympio in Togo in 1963, Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso in 1987 and others.” Between 1997 and 2002, during the presidency of Jacque Chirac, France intervened militarily 33 times on the African continent (by comparison, between 1962 and 1995, France intervened militarily 19 times in African states). France never really suspended its colonial grip or its colonial ambitions.

Breaking the Camel’s Back

Two events in the past decade “broke the camel’s back,” Noudjenoume said: the NATO war in Libya, led by France, in March 2011, and the French intervention to remove Koudou Gbagbo Laurent from the presidency of Côte d’Ivoire in April 2011. “For years,” he said, “these events have forced a strong anti-French sentiment, particularly among young people. It is not just in the Sahel that this feeling has developed but throughout French-speaking Africa. It is true that it is in the Sahel that it is currently expressed most openly. But throughout French-speaking Africa, this feeling is strong.”

Mass protest against the French presence is now evident across the former French colonies in Africa. These civilian protests have not been able to result in straight-forward civilian transitions of power, largely because the political apparatus in these countries had been eroded by long-standing, French-backed kleptocracies (illustrated by the Bongo family, which ruled Gabon from 1967 to 2023, and which leeched the oil wealth of Gabon for their own personal gain; when Omar Bongo died in 2009, French politician Eva Joly said that he ruled on behalf of France and not of his own citizens). Despite the French-backed repression in these countries, trade unions, peasant organizations, and left-wing parties have not been able to drive the upsurge of anti-French patriotism, though they have been able to assert themselves

France intervened militarily in Mali in 2013 to try to control the forces that it had unleashed with NATO’s war in Libya two years previously. These radical Islamist forces captured half of Mali’s territory and then, in 2015, proceeded to assault Burkina Faso. France intervened but then sent the soldiers of the armies of these Sahel countries to die against the radical Islamist forces that it had backed in Libya. This created a great deal of animosity among the soldiers, Noudjenoume told us, and that is why patriotic sections of the soldiers rebelled against the governments and overthrew them. Read more