Ella Shohat ~ Rupture And Return. A Mizrahi Perspective On The Zionist Discourse

Eurocentric norms of scholarship have had dire consequences for the representation of Palestinian and Mizrahi history, culture and identity. In this paper I would like to examine some of the foundational premises and substratal axioms of hegemonic discourse about Middle Eastern Jews (known in the last decade as “Mizrahim”). Writing a critical Mizrahi historiography in the wake of colonialism and nationalism, both Arab and Jewish, requires the dismantling of a number of master-narratives. I will attempt to disentangle the complexities of the Mizrahi question by unsettling the conceptual borders erected by more than a century of Zionist discourse, with its fatal binarisms of savagery versus civilization, tradition versus modernity, East versus West and Arab versus Jew. This paper forms part of a larger project in which I attempt to chart a beginning for a Mizrahi epistemology through examining the terminological paradigms, the conceptual aporias and the methodological inconsistencies plaguing diverse fields of scholarship concerning Arab Jews/Mizrahim.

Central to Zionist thinking is the concept of “Kibbutz Galuiot“– the “ingathering of the exiles.” Following two millennia of homelessness and living presumably “outside of history,” Jews can once again “enter history” as subjects, as “normal” actors on the world stage by returning to their ancient birth place, Eretz Israel. In this way, Jews can heal a deformative rupture produced by exilic existence. This transformation of “Migola le’Geula” – from Diaspora to redemption – offered a teleological reading of Jewish History (with a capital H) in which Zionism formed a redemptive vehicle for the renewal of Jewish life on a demarcated terrain, no longer simply spiritual and textual, but rather national and political. Concomitant with the notion of Jewish “return” and continuity was the idea of rupture and discontinuity. In order to be transformed into New Jews, (later Israelis) the Diaspora Jews had to abandon their Diaspora – galuti – culture, which in the case of Arab- Jews meant abandoning Arabness and acquiescing in assimilationist modernization, for “their own good,” of course. Within this Promethean rescue narrative the concepts of “ingathering” and “modernization” naturalized and glossed over the epistemological violence generated by the Zionist vision of the New Jew. This rescue narrative also elided Zionism’s own role in provoking ruptures, dislocations and fragmentation, not only for Palestinian lives but also – in a different way – for Middle Eastern/North African Jews. These ruptures were not only physical (the movement across borders) but also cultural (a rift in relation to previous cultural affiliations) as well as conceptual (in the very ways time and space were conceived). Here I will critically explore the dialectics of rupture and return in Zionist discourse as it was formulated in relation to Jews from the Middle East/North Africa. I will examine these dialectics through the following grids: a) dislocation: space and the question of naming; b) dismemberment: the erasure of the hyphen in the “Judeo-Muslim;” c) dis-chronicity: temporality and the project of modernization; d) dissonance: methodological and discursive ruptures.

The complete paper: https://www.juragentium.org/topics/palestin/doc07/en/shohat.htm

Published in Jura Gentium, Rivista di filosofia del diritto internazionale e della politica globale, ISSN 1826-8269

Translating The Arab-Jewish Tradition: From Al-Andalus To Palestine/Land Of Israel

This essay investigates the vision of two Jewish scholars of a shared Arab-Jewish history at the beginning of the twentieth century.

The first part of the essay focuses on Abraham Shalom Yahuda’s re-examination of the Andalusian legacy in regard of the process of Jewish modernisation with respect to the symbolic and the actual return to the East. The second part of the essay centers on the work of Yosef Meyouhas (1863-1942), Yahuda’s contemporary and life-long friend who translated a collection of Biblical stories from the Arab-Palestinian oral tradition, examining the significance of this work vis-à-vis the mainstream Zionist approach.[1]

A Dispute in Early Twentieth-Century Jerusalem

On a winter’s evening late in 1920, in an auditorium close to Jerusalem’s Damascus Gate (“bab al-‘amud”), Professor Abraham Shalom Yahuda (1877-1951) gave a lecture attended by an audience of Muslim, Christian and Jewish Palestinian intellectuals and public figures.[2] Its subject matter was the glory days of Arabic culture in al-Andalus.

The event was organized and hosted by the Jerusalem City Council in honour of the newly appointed British High Commissioner Herbert Samuel (1870-1963). In his opening address, Mayor Raghib al-Nashashibi (1881-1951) introduced the speaker as a Jerusalemite, son of one of the most respected Jewish families in the city.[3]

In his lecture, delivered in literary Arabic, Abraham Shalom Yahuda, since 1914 Professor of Jewish History and Literature and Arabic Culture at the University of Madrid portrayed the golden era of Muslim Spain describing the great accomplishments of Muslims and Jews during this period in the fields of science, literature, philosophy, medicine and art and emphasizing the fruitful relations between them. This event was an important moment in the life of this scholar of Semitic culture, one in which his long-standing scientific and political projects merged.

From his early days in Jerusalem, and later on in Germany as a student in Heidelberg and as a lecturer at the Berlin “Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums” (1904-1914), Yahuda had focused on the Andalusian legacy, emphasising the historical and philological aspects of the Judeo-Muslim symbiosis during that period and its symbolic significance for the modernization and revitalization of Jewish and Hebrew culture. This issue was at the heart of Yahuda’s long-standing debate with Jewish scholars regarding the different options for Jewish modernization. Towards the end of his lecture, Yahuda addressed the Arab Palestinians in the audience directly. Speaking from the heart, albeit in a slightly pompous tone, he called on them to revive the legacy of al-Andalus:

If the opportunity exists today for the Arabs to return to their ancient Enlightenment, it has been made possible only by virtue of the empires that fought for the rights of suppressed peoples.

If the Arabs revive their glorious past through the good will of these empires, especially that of Great Britain, which is willing to help them as much as possible, they have to return to their essence of generosity and allow the other suppressed peoples, including the People of Israel, to benefit from the national rights granted by the British Government. Only when the spirit of tolerance and freedom that prevailed in the golden age of Arab thought in al-Andalus […] will return to prevail today, in a way that will enable all peoples, without religious or ethnic prejudice, to work together for the revival of enlightenment in the Eastern nations, each people according to its unique character and traditions, can an all-encompassing Eastern enlightenment be reborn that will include all Eastern nations and peoples.[4]

Thus, Yahuda chose to end his lecture with a political statement regarding the future of Palestine in this new imperial era. Well aware of the importance of his words in such dramatic times, Yahuda proposed a symbolic return to al-Andalus as a potential political and cultural platform for Jews and Arabs in post-Ottoman Palestine. While it is hard not to see an affinity with the British Empire in his words, we should however note the unique context in which this lecture took place: a few months after the official beginning of British Mandatory rule in Palestine, at an occasion dedicated to the newly appointed High Commissioner Herbert Samuel and in his presence.[5]

However, the event also had a more specific historical context, as it took place on the same night that the third Arab National Congress opened in Haifa. The lecture was organized by Raghib al-Nashashibi in honour of Herbert Samuel, and Nashashibi invited Yahuda to give the main lecture. As the historian Safa Khulusi has suggested, this clash was probably not coincidental, but rather was part of the internal political struggle within the Arab Palestinian community.[6]

During the end of the Ottoman period, and more intensively throughout the British Mandate, the Palestinian political leadership was deeply divided between a few notable families.

The rivalry between the two leading Jerusalemite families—the Nashashibis and the Husseinis—split the local leadership into two main camps: the national camp, under Haj Amin al-Husseini, and the opposition camp, led by Raghib al-Nashashibi. Both families drew supporters from other elite families and refused to cooperate with each other, resulting in a deep political divide in Palestinian society.[7]

This split, which dominated the Palestinian political arena throughout the Mandatory period, had its origins in the early days of British rule, when Raghib al-Nashashibi was appointed Mayor of Jerusalem after the British Military Commissioner removed Musa Kazim al-Husseini (1853-1934) from office.[8]

The three-day Arab congress in Haifa was organized by members of the al-Husseini family and led by Kazim al-Husseini.

Just a few months after the French army destroyed the short-lived constitutional Arab Kingdom of Syria under King Faysal (1885-1933), and amid the ruins of the first modern Arab state in Bilad al-Sham (Greater Syria) that projected equal citizenship to all, the participants in the Haifa congress sought to establish a new strategy towards British rule and towards the Balfour Declaration and the notion of a homeland for the Jewish people.

The British Institute for the Study of Iraq – The Jews of Iraq Conference ~ 16-18 September 2019

Panel 1 – Linda Abdulaziz Menuhin speaks on her memoires, memories and personal history.

The conference aimed to evaluate the many contributions of the Jewish community in Iraq within the spheres of the arts and culture, social policy, education, government and the economy in the early modern and modern period. Iraqi Jews constituted one of the world’s oldest and most historically significant Jewish communities and were in Iraq for over 2,500 years. There is a widening academic interest in the history and contributions of the Jewish community as well as growing interest in Jewish history in contemporary Iraq. This conference brought together UK, Iraqi and international scholars interested in exploring and researching the contributions of this important community to modern Iraq.

Day 2 – Prof Zvi Ben-Dor Benite (NYU) and Prof Orit Bashkin (UofChicago) give a historical overview on the Jews of Iraq.

Conference 16-18 September 2019 at SOAS, London. The conference was organised by the British Institute for the Study of Iraq in collaboration with The Center for Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Chicago and the Department of History, Religions and Philosophies at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London.

Please visit the YouTube Channel of The British Institute for the Study of Iraq for more uploads:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCCZbB7O-JU7nYzdh2YkNWfg

Iraqi-Jewish Oral History | Ghetto In Diwaniya, Iraq 1941: Lynette’s interview With Daniel Sasson

Jan. 15, 2020 ראיון עם דניאל ששון בעברית עם כתוביות באנגלית: הגטו בדיווניה, עיראק

I had the honor of interviewing Daniel Sasson about his book, “The Untold Story” (available in Hebrew). Inspired by the ghettos in Europe during the Holocaust in 1941, then Iraqi Prime Minister Rashid Ali set up a Nazi-like ghetto for over 600 Jews in the small city of Diwaniya, located just outside Baghdad.

Daniel was only 5 years old, and his family was one of the most prominent Jewish families in Iraq at the time. A couple days after the ghetto’s release came the ‘Farhud’, a pogrom in which hundreds of Jewish homes were looted and destroyed, 200 Jews murdered, thousands injured, and Jewish life in Iraq forever changed. Its 79th anniversary was a few days ago.

Daniel was one of my first interviewees last summer, when I was conducting interviews for my Master’s thesis. I spent the entire Fall semester processing the things he and other interviewees told me– stories I couldn’t get out of my head for months. I am honored to have met such a resilient person like him, and I believe that English-speaking communities have so much to gain by learning about the stories and experiences of Iraqi Jews.

(If the English translations don’t come up automatically, press “CC”)

היה לי כבוד להיפגש עם דניאל ששון ולדבר על הספר שלו, “הסיפור שלא סופר,” על הגטו הראשון (והאחרון) בעיראק. אין לי מספיק מילים להודות לו על ההזדמנות הזאת. למדתי על ההשפעה של הנאציים בעיראק, חיים שלו בבגדד, ומה קרה בתוך הגטו. הקהילה היהודי העיראקית חזקה מאוד, עשירה, ומלא עם סיפורים מדהימים– זה כדאי לשמוע, להבין, וללמוד מהם.

אם אין כתוביות באנגלית, לחץ על “cc”

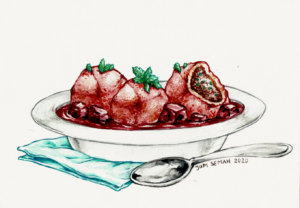

The Art of Cooking – Kubba Shawandar

This dish reminds me of my grandmother in Israel. Whenever I visited my grandmother as a kid this was what I was looking forward to the most.

This dish reminds me of my grandmother in Israel. Whenever I visited my grandmother as a kid this was what I was looking forward to the most.

And my grandmother knew this and always made sure to fill my plate with kubba!

The smell of cooking this dish gives me a great feeling of nostalgia.

Kubba Shawandar looks more difficult to make then it is and I hope you will try it out yourself.

The ingredients are very easily obtained and the flavour is a classic Iraqi Jewish taste.

Ingredients:

For the soup:

3 medium sized onions

4 medium sized red beets ( or 2 cans )

1 small can tomato paste

1 lemon

2 dried bay leafs

sugar

salt & pepper

paprika powder

olive oil

1 liter of chicken broth

Beef mixture:

lean ground beef

1 onion

salt

fresh parsley

ras el hanout

turmeric

Kubba dough:

semolina

water

salt

Making the kubba balls:

Start with mixing the beef with minced onion and minced parsley in a bowl.

Add the salt, ras el hanout and turmeric and mix well.

(make a small patty and pan fry it, taste this for salt and seasoning make sure it is not too bland)

In another bowl add 2 cups of semolina with salt and 1 cup of water mix until it is a sticky dough.

Do not over mix it and make sure it stays sticky and does not become a dry dough.

Next let’s make these kubba balls. In your hand take a small ball of dough and press a hole in it with your thumb.

Add the beef mixture into the dent and start folding the rest of the dough around it.

Once the beef has been covered squeeze the ball lightly and roll it around in your hand to form it into a ball shape.

When done place it on a non-stick surface and continue making the rest, do not let them touch each other!!!

(you can be a bit rough with making these balls)

Making the soup:

In a big pot we start with caramelizing diced onions with olive oil.

When the onions become translucent add all the dry ingredients.

(bay leafs, salt, sugar & pepper, paprika powder)

Give a quick mix and when all the dry ingredients have become a single mixture add the bite size diced red beets.

Fry for a couple of minutes on low heat, when it starts to become dry add the tomato paste, chicken stock and lemon juice.

Mix well!

Wait until the soup starts simmering on low heat.

Once the soup starts simmering gently place the kubba balls we made to the soup. These solidify very quickly once they go into the soup.

Add all the balls to the soup. You can make small meatballs with any leftover meat and throw them to the soup as well.

Make sure everything is covered with liquid and simmer for 45 minutes.

Always taste for salt before serving!

Garnish with some fresh parsley.

Kubba Shawandar has a neutral taste and works well with some salad, bread or rice.

Beteavon!

Eleonore Merza ~ The Israeli Circassians: Non-Arab Arabs

Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem (2012) One day, I was at the tahana merkazit [central bus station] in Jerusalem with Mussa and we went through the metal detector. They let him go through but when it was my turn, they asked for my identity card. They saw that we kept talking together so they asked for his I.D. too. He is a redhead and has blue eyes so they thought he was Ashkenazi. But they saw his name ‘Musa’ – that sounds quite Arabic and they asked him if he was Arab, but then his family name doesn’t sound Arabic at all so he explained that he was Circassian. Then, they asked him what religion he was and he said ‘Muslim’. They were dumbfounded…

Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem (2012) One day, I was at the tahana merkazit [central bus station] in Jerusalem with Mussa and we went through the metal detector. They let him go through but when it was my turn, they asked for my identity card. They saw that we kept talking together so they asked for his I.D. too. He is a redhead and has blue eyes so they thought he was Ashkenazi. But they saw his name ‘Musa’ – that sounds quite Arabic and they asked him if he was Arab, but then his family name doesn’t sound Arabic at all so he explained that he was Circassian. Then, they asked him what religion he was and he said ‘Muslim’. They were dumbfounded…

The 4,500-odd Israeli Circassians, who arrived during the second half of the 20th century in what was then part of the Ottoman Empire, have an unusual identity: they are Israelis without being Jews and they are Muslims but aren’t Palestinian Arabs (they are Caucasians). Little known by the Israeli public, the members of this inconspicuous minority often experience situations like the one reported above; indeed, many of them have a fair complexion and light-colored eyes that don’t match the widely spread (and expected) clichés about Muslims’ physical traits. At the same time, many Circassians – men, in particular – bear a Muslim name, which immediately causes them to be classified as “Arabs.”

Until 1948, the Zionist project’s exclusive aim was the establishment of a Jewish state – not the establishment of a state where Jews could finally live far from the anti-Semitic threat. In The Jewish State, Theodor Herzl had already stated that “the nations in whose midst Jews live are all either covertly or openly Anti-Semitic”2 and the establishment of a Jewish state was the future as Zionism saw it. In fact, when the State of Israel was declared, it was defined as the state of the Jewish people, inheritor of the Biblical land of Israel and of the kingdom of Judah. This exclusive definition has made the creation of citizenship categories quite arduous. Actually, some figures of Zionism opposed Herzl’s political Zionism even before the creation of the state. One of them was Asher Hirsch Ginsberg, better known under his pen name Ahad Ha’am. Even though Ahadd Ha’am received the Zionist circles’ moral support, he was convinced that the future state could not ingather all the Jews and he fought Herzl’s political Zionism. After his visits in Palestine, the author wrote down his impressions and criticized the functioning of settlements. In his essay Emet me-Eretz Yisrael [A Truth from Eretz Yisrael], he denounced the myth of the virgin land conveyed by the Zionist leaders and reminded them that their analysis did not take into account the Arabs:

From abroad, we are accustomed to believe that Eretz Israel is presently almost totally desolate, an uncultivated desert, and that anyone wishing to buy a land there can come and buy all he wants. But in truth it is not so. In the entire land, it is hard to find tillable land that is not already tilled […] We are accustomed to believing that Arabs are all desert savages, like donkeys who do not see or understand what is going on around them. This is a serious mistake.

The complete essay: https://journals.openedition.org/bcrfj/7250

Référence électronique

Eleonor Merza,The Israeli Circassians: non-Arab Arabs, Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem [En ligne], 23 | 2012, mis en ligne le 20 février 2013, Consulté le 10 juin 2020.

Eleonore Merza is a political anthropologist; she completed her doctorate at the EHESS. She is an associate researcher in the Anthropology of Organizations and Social Institutions Research Unit at the Interdisciplinary Institute for the Anthropology of Contemporary Societies (IIAC-LAIOS: CNRS-EHESS). She currently pursues post-doctoral studies at the French Research Center in Jerusalem (CRFJ). Her doctoral thesis focused on the identity of the Circassian minority in Israel and her current research deals with non-Jewish citizens, minorities, and co-existence in today’s Israeli society. She taught at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS) where she was a lecturer on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.