The Kingdom Of The Netherlands In The Caribbean. 50 Jaar Statuut en verder

Inleiding

Inleiding

We vieren vandaag de 50e verjaardag van het Statuut voor het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden[i]. In de aanloop naar die viering zijn symposia gehouden en talloze lezingen gegeven. Ook hier in de aula van de UNA. In dat verband is dit de zoveelste lezing en het is bijna onmogelijk om nog iets nieuws toe te voegen aan alles wat al gezegd is. Bovendien is niet alleen in de laatste weken veel gezegd over het Statuut en de Koninkrijksrelaties; dat wordt al 50 jaar gedaan. We kennen over het algemeen de beelden en de opvattingen.

In een poging aan dat alles nog iets toe te voegen kies ik twee invalshoeken. De ene is die van de historische beeldvorming en de andere is die van de in de discussie over het Statuut gebruikte begrippen. Beide problemen zijn belangrijk, omdat ze ons beeld van het Statuut en de koninkrijksrelaties bepalen. Beide zijn ook problematisch.

Bewustzijn van het heden is onmogelijk zonder besef van het verleden. Dat verleden bestaat vaak in mentale beelden, waarin we gevangen zitten. Daardoor worden we ook tot slachtoffer van ons verleden, gevangen in de voorstelling van onze vaak tot elke prijs gekoesterde beelden. Bevrijding uit die beelden is dan nodig om het heden beter te kunnen begrijpen. Niemand is slachtoffer van het verleden, velen zijn wel het slachtoffer van hun eigen beelden van het verleden. In onze tijd wordt langzamerhand, maar aanzienlijk méér dan 50 jaar geleden, duidelijk hoezeer de officiële versie van de geschiedenis van de mensheid een gemáákte geschiedenis is, vaak ver bezijden de complexe waarheid over wat werkelijk is gebeurd. Het is ‘een open deur’ om te beweren dat de geschiedenis meestal geschreven is vanuit het perspectief van de overwinnaar, vaak vergezeld van de om gehoor vragende alternatieve versie van de slachtoffers, waardoor allerlei zwart-wit beelden zijn ontstaan, die vooral dienst moeten doen om de eigen actuele positie te rechtvaardigen. Het zal nog aanzienlijk meer moeite kosten om de werkelijkheid van de geschiedenis te achterhalen dan mogelijk is in de obligate discussies tussen winnaars en slachtoffers, of tussen de nazaten van kolonisten en die van slaven. In die zin is de geschiedenis van kolonisatie en dekolonisatie, maar ook die van de slavernij en de emancipatie nog bij lange na niet geschreven. De mogelijkheid om die wél te schrijven vergt in elk geval het vermogen om de eigen identificatie met de voorstellingen van het ene of het andere standpunt los te laten. Voor de werking van het 50 jaar geleden overeengekomen Statuut is dat punt nog lang niet bereikt. Integendeel, het Statuut lijkt na 50 jaar meer dan ooit nog de meetlat te zijn aan de hand waarvan het eigen historische gelijk wordt geïllustreerd.

Hetzelfde geldt voor de begrippen die we gebruiken om bewustzijn van een stand van zaken te krijgen. Die begrippen zijn meestal onzuiver. Dat is voor een deel het gevolg van het heersende rationalisme in de wetenschap. Dat rationalisme sluit ons door de eigen aard ervan op in subjectieve, onzuivere begrippen, waar de werkelijkheid dan achter schuil gaat. Ook dat is bij het Statuut in hoge mate het geval. We hanteren de begrippen van staat, vrijheid, gelijkheid en samenwerking alsof die een vanzelfsprekende inhoud hebben. De werkelijkheid is vaak heel anders. Om dat te kunnen zien, moeten die begrippen steeds weer opnieuw worden doordacht. Het Statuut beantwoordt in die zin aan de mogelijkheden en onmogelijkheden van het geldende rechtsbewustzijn. In algemene zin is dat het rechtsbewustzijn van de zich ontwikkelende rechtsstaat. Voor velen is de rechtsstaat de meest ideale vorm, waarin een politieke gemeenschap kan bestaan. Er is echter veel meer voor te zeggen om de rechtsstaat te beschouwen als een juridisch ‘doorgangshuis’, waarvan het begrip wordt bepaald, en begrensd, door de beperkte bewustzijnsmogelijkheden van het heersende wetenschappelijk rationalisme, dat de wereld maakt tot een met het ego van de mensen verbonden mentale constructie.[ii] Het Statuut, waarin rechtsculturen met een geheel verschillende beleving van politieke moraliteit, begripsmatig met elkaar worden verbonden is er, ook nu meer dan ooit, het levendige bewijs van. Dezelfde regels worden door de één als politieke autonomie en door de ander als bewijs van neokoloniale intenties opgevat. Meer bewijs voor de stelling dat de begrippen van de rechtsstaat subjectief en onzuiver zijn, lijkt nauwelijks denkbaar. Maar ook hier geldt dat vooruitgang slechts kan worden geboekt in die mate waarin men bereid is de identificatie van het eigen zelf met de quasi rationele constructies van het geldende recht te doorzien en los te laten.

Dat zijn de twee met elkaar samenhangende hoofdproblemen van vandaag, ook voor een behandeling van de Koninkrijksrelaties en voor de problematiek van 50 jaar Statuut. Het eerste, dat van de subjectieve beelden van de geschiedenis, is nog het eenvoudigste. Niet omdat het opbouwen van een waar beeld van de geschiedenis eenvoudig zou zijn, maar omdat het verzet daartegen vooral emotioneel is. Het tweede, dat van de ontoereikendheid van wetenschappelijke begrippen en theorieën, is het moeilijkste. Dat komt omdat als gevolg van de aangeduide ontwikkeling vaak het bewustzijn ontbreekt voor het begrip ervan[iii]. Waar men bij het eerste probleem vooral stuit op emoties, stuit men bij het tweede probleem vaak op de blinde vlek van het onbegrip, in de wetenschap niet minder dan daarbuiten.

Beide problemen zijn ook complementair: door de rationalisatie in het denken raakt in de beleving van de mensen het belang van de geschiedenis op de achtergrond. Op middelbare scholen kan men het vak ‘laten vallen’ en de universiteiten beschouwen de studie van de geschiedenis van de afzonderlijke vakgebieden vooral als de franje van de opleiding. Door gebrekkige beleving van de geschiedenis verdwijnt vervolgens ook hoe langer hoe meer de mogelijkheid de werking van allerlei begrippen te achterhalen. De wereld wordt er één van modellen en protocollen. Alles wordt hetzelfde, in een eindeloze herhaling van eenmaal ingenomen standpunten.

Met deze opmerkingen in het achterhoofd wil ik toch iets zeggen over 50 jaar Statuut. Om te beginnen een korte terugblik naar de koloniale verhoudingen en de overgang naar de hedendaagse statutaire verhoudingen binnen het Koninkrijk. Vervolgens een enkele opmerking over de juridische problematiek van het Statuut. Daarna wat over de mogelijkheden van vandaag, waarbij ik graag wat kwijt wil over economische ontwikkelingsmodellen. Ten slotte moet er dan nog aandacht zijn voor de toekomst: 50 jaar Statuut, en hoe nu verder? Read more

The Kingdom Of The Netherlands In The Caribbean. Constitutional In-Betweenity: Reforming The Kingdom Of The Netherlands In The Caribbean

The Kingdom of the Netherlands is an ambiguous construction that served a useful purpose in the 1950s by accommodating the desire for autonomy in the Caribbean territories within a structure that still appeared to uphold Dutch sovereignty, while also silencing international demands for decolonisation [i]. Since the 1960s, dissatisfaction with the structure has been mounting. In many similar situations the mounting tensions were relieved by the drastic move of declaring the independence of the overseas territories. In the case of the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba a conscious decision was made not to sever the ties. Since then, it has often been stated (mainly in the Netherlands) that the constitution of the Kingdom is outdated, but nothing came of the various attempts at modernisation.[ii] Currently a new attempt is being made, which will perhaps involve a redesign of a number of key elements of the Kingdom structure.

The Kingdom of the Netherlands is an ambiguous construction that served a useful purpose in the 1950s by accommodating the desire for autonomy in the Caribbean territories within a structure that still appeared to uphold Dutch sovereignty, while also silencing international demands for decolonisation [i]. Since the 1960s, dissatisfaction with the structure has been mounting. In many similar situations the mounting tensions were relieved by the drastic move of declaring the independence of the overseas territories. In the case of the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba a conscious decision was made not to sever the ties. Since then, it has often been stated (mainly in the Netherlands) that the constitution of the Kingdom is outdated, but nothing came of the various attempts at modernisation.[ii] Currently a new attempt is being made, which will perhaps involve a redesign of a number of key elements of the Kingdom structure.

Since 1981 it has been recognized by the governments of the Countries and the island territories that the populations of the islands have the right to self-determination. This right should play a prominent role in any process of constitutional reform of the Kingdom, it has often been repeated. Reference is also often made to the law of decolonization as developed at the United Nations, although difference of opinion exists on what this means for the Kingdom relations.[iii] While the law provides no readymade solutions to the constitutional problems of the Kingdom, it does contain some principles that should guide the restructuring of the Kingdom.

The constitutional character of the Kingdom

The constitutional reform of the Kingdom that has been on the cards for several decades now, has been made more difficult by the persistent differences of opinion on the legal character of the relations between the Netherlands and the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba. Some view the Kingdom as a confederation or some other very loose form of entirely voluntary cooperation between the Netherlands and two semi-independent states. Others see the Kingdom as a fully-fledged state with its own powers and responsibilities. Both views have their merits, because the Kingdom is an example of constitutional in-betweenity[iv] that defies classification in any of the traditional models of statehood.

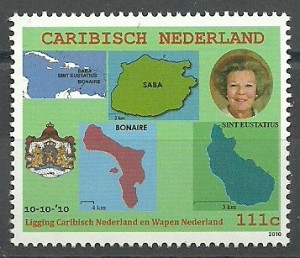

The Kingdom consists of three equivalent Countries (Landen in Dutch). The two Caribbean Countries ‘Aruba and the Netherlands Antilles’ have a large amount of autonomy, even larger than the Country in Europe some would say, because that Country has delegated many of its authorities to the European Union. The constitution of the Kingdom, entitled Het Statuut voor het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden (the Charter for the Kingdom of the Netherlands), authorizes the government of the Kingdom to enter into relations with foreign states, and also charges the government with the ultimate responsibility in the areas of human rights, good government and the military defence of the Kingdom. The Kingdom government has few other tasks. Whether the Kingdom has any other institutions or organs has been the subject of a legal debate, which is probably of little importance because most of the other tasks of the Kingdom are performed by the Country of the Netherlands. The Kingdom Charter contains some elements that resemble a federal system[v], but these elements have played only a minor role in practice.

It has sometimes been defended that the Country in Europe is a state under international law,[vi] but it is generally assumed that only the Kingdom as a whole possesses statehood. Writers on international law nonetheless often classify the Kingdom as a form of association, which is also how the Netherlands defended it at the UN in 1955 and afterwards.[vii] The recognition of the right to self-determination of the Caribbean Countries at the Round Table Conference of 1961, confirmed many times thereafter, also suggests that the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba have a separate legal status that could perhaps best be described as a constitutional association with the Netherlands. This captures the somewhat paradoxical position of the Caribbean Countries – belonging to the Kingdom, but not belonging to the Netherlands – which seems to have been the aim of the framers of the Charter in 1954. Read more

The Kingdom Of The Netherlands In The Caribbean. Suriname 1954 – 2004: Kroniek van een illusie

De weg naar onafhankelijkheid

De weg naar onafhankelijkheid

Het Statuut voor het Koninkrijk van 1954 bepaalde dat de kolonie Suriname een autonoom deel van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden werd onder een eigen, democratisch gekozen regering. Eenentwintig jaar later, in 1975, werd Suriname een onafhankelijke republiek [i]. De politieke stabiliteit van Suriname berustte van 1958 tot 1967 op de samenwerking tussen de Creoolse partijen NPS en PSV en de Hindostaanse VHP. Na de algemene verkiezingen van 1967 kwam het tot een breuk tussen de NPS en de VHP en regeerde Pengel verder zonder de VHP. Het nieuwe kabinet Pengel kreeg al snel problemen met de grote maatschappelijke organisaties. Steen des aanstoots was de corruptie, de verkwisting van overheidsgelden en het patronagestelsel. De ontevredenheid vond een hoogtepunt in een massale staking van de onderwijsbonden in 1969.Het kabinet viel en het zakenkabinet Sedney schreef in hetzelfde jaar nieuwe verkiezingen uit. De VHP werd de grootste partij en vormde met enkele kleinere Javaanse partijen een nieuw kabinet, dus nu werd de NPS uitgesloten.

In de regeringsverklaring van 1969 kwam uitdrukkelijk te staan dat de regering geen prioriteit zou verlenen aan een staatkundige zelfstandigheid. Als reactie daarop maakten de Creoolse partijen de onafhankelijkheid tot een nationaal discussiethema. De dood van Pengel in 1970 en de overname van de macht binnen de NPS door een nieuwe generatie links-nationalistische leiders maakten in 1973 de weg vrij voor een coalitie tussen deze partij en de nationalistische PNR van Bruma. De PNR had daarbij ‘maar wel in het geheim’ bedongen dat bij een verkiezingsoverwinning de onafhankelijkheid op korte termijn moest worden afgekondigd.

De regering-Arron die in 1973, na de door de PNK (een coalitie van de NPS, de PNR, de katholieke PSV en de Javaanse KTPI) gewonnen verkiezingen aantrad, vond in het Nederlandse kabinet-Den Uyl een bondgenoot voor een onafhankelijk Suriname. Op 15 februari 1974 deelde minister-president Arron mee dat Suriname ‘ultimo 1975’ een onafhankelijke republiek zou worden. De wettige Surinaamse regeringsleider had de onafhankelijkheid aangekondigd en Nederland wilde van Suriname af, dus de onafhankelijkheid kon snel bezegeld worden. De onderhandelingen over de onafhankelijkheid stonden voornamelijk in het teken van de hoogte van de ontwikkelingshulp. Nederlandse onderhandelaars waren buitengewoon toeschietelijk. Men werd het na loven en bieden eens over een schenking van 3,5 miljard (niet-geïndexeerd) en kwijtschelding van uitstaande schulden.

Meningsverschil bestond er wel over het nut van een Surinaams leger, maar omdat Suriname dit zo belangrijk vond, maakte Nederland er geen punt van. Een Surinaamse leger zou de Nederlandse Troepenmacht In Suriname (TRIS) gaan vervangen. De onderhandelaars kwamen uit op een ‘Surinamisering van de TRIS’ tot een Surinaamse Krijgsmacht (SKM) met een sterkte van 620 man met officieren en (ongeveer honderd) onderofficieren van Surinaamse afkomst die in het Nederlandse leger dienden, op basis van gulle suppletie-, salaris- en kinderbijslagregelingen.[ii] Aan de ambassade van Nederland in Paramaribo werd een Nederlandse militaire missie (van zeven personen) verbonden om Suriname te helpen bij de opbouw van de Strijdmacht. Leider van deze missie werd kolonel Valk.

De Hindostaanse bevolkingsgroep was fel gekant tegen de onafhankelijkheid. Uiteindelijk ging de Hindostaanse oppositie pas overstag nadat de VHP parlementariër Hindorie meestemde met de NPK. Zo bleek één stem de onafhankelijkheid te bezegelen. Even vóór 25 november 1975, de dag van de onafhankelijkheid van de republiek Suriname, verzoenden Arron en Lachmon zich in het publiek. Gouverneur Ferrier werd president Ferrier. Suriname werd daarmee een zelfstandige staat, maar was beslist geen natie; het land was de optelsom van een groot aantal etnische groeperingen waartussen de politieke eenheid niet bijster groot was. Bijna honderdduizend Surinamers vertrokken in de maanden rond de onafhankelijkheid naar Nederland.[iii] In die zin zou men kunnen beweren dat Suriname, nadat het als uitkomst van onderhandelingen tussen de Nederlandse en Surinaamse politieke elite onafhankelijk was geworden zonder plebisciet, met de voeten stemde. Read more

The Kingdom Of The Netherlands In The Caribbean. Bio Notes: Biografische gegevens van de auteurs

Mr. Dr. Douwe A. A. Boersema (1948) is Associated Professor of Public Law at the University of the Netherlands Antilles at Curaçao. During 1975-2000 he lectured Constitutional Law and History of Political Philosophy at Groningen University in the Netherlands. In 1998-1999 he lectured Public Law at the University of Aruba. He studied Psychology and Law at Groningen University and got there his PhD on a thesis on the development of the consciousness of law regarding the concept of equality and human rights from Greek Antiquity up to our time. He has written articles on the development of law, human rights and judicial problems in relation to cultural diversity and minorities. He has worked as a consultant for legal problems and transition management.

Mr. Dr. Douwe A. A. Boersema (1948) is Associated Professor of Public Law at the University of the Netherlands Antilles at Curaçao. During 1975-2000 he lectured Constitutional Law and History of Political Philosophy at Groningen University in the Netherlands. In 1998-1999 he lectured Public Law at the University of Aruba. He studied Psychology and Law at Groningen University and got there his PhD on a thesis on the development of the consciousness of law regarding the concept of equality and human rights from Greek Antiquity up to our time. He has written articles on the development of law, human rights and judicial problems in relation to cultural diversity and minorities. He has worked as a consultant for legal problems and transition management.

Denicio Brison B.Sc. LL.M. (1952) practices law on St. Maarten, and spent the first part of his career (circa 20 years) in the hotel industry primarily on Sint Maarten and Aruba. In this field he was exposed on a daily basis to the contradictions of working in an environment that catered to well-to-do North American tastes and the realities of living in the Caribbean. His influence and outlook is different from most Antillians in that he chose never to live in nor visit the Netherlands but instead attended college in Trinidad and the U.S. where he earned a B.Sc. in Hotel Administration from the University of Nevada at Las Vegas. Later he earned a degree in Law at the University of the Netherlands Antilles. His area of interest is Constitutional and Public Law. He writes a regular newspaper column on general topics of law and is a frequent speaker on local radio on legal matters.

Mr. Antonito (Mito) Croes (1946, Aruba) is na enige jaren ambtenaar en vervolgens hoofdwetenschappelijk medewerker staatsrecht aan de Universiteit van de Nederlands Antillen te zijn geweest in de politiek gegaan. Hij meer minister van Staatkundige Structuur van de Nederlandse Antillen, Minister van Welzijnszaken van Aruba en acht jaar Gevolmachtigde Minister van Aruba in Nederland. Hij heeft diverse wetenschappelijke publicaties op zijn naam, met name over de staatkundige verhoudingen binnen het Koninkrijk en deugdelijkheid van bestuur. Hij werkt nu aan een proefschrift over toekomstopties voor het Koninkrijk.

Drs. Francio Guadeloupe (1971) works at the Anthropology and Sociology Department of the University of Amsterdam. After having lived and traveled throughout the Caribbean, he moved to the Netherlands at 18 years of age. In 1999, he obtained his Master’s degree in Anthropology/Development Studies at the Radboud University of Nijmegen. Guadeloupe has published two books on Brazil: A vida e uma dança: the Candomble Through the Lives of Two Cariocas (Nijmegen, CIDI, 1999), and Dansen om te leven: over Afro-Braziliaanse cultuur en religie (Luyten & Babar, 1999). Guadeloupe has researched how popular radio disc jockeys on the bi-national island of Saint Martin (French) & Sint Maarten (Dutch) combine Christian derived ethics and Caribbean music to forward a politics of belonging which includes autochthons as well as newcomer population. This research is the basis of his PhD thesis which he’s in the process of putting the final touches to.

Mr. drs. Steven Hillebrink (1968) worked from 1999 until 2004 at the University of Leiden, where he taught Constitutional and Administrative Law. He has published articles on Kingdom legislation and the right to self-determination of the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba. He is currently writing a PhD thesis on the role of the international right to self-determination in the relations between the Netherlands, the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba. Since 2004, he is employed at the constitutional affairs and legislation department of the Dutch ministry of the Interior and Kingdom relations.

Wim Hoogbergen (1944) is senior lecturer in Caribbean Studies, department Cultural Anthropology at Utrecht University, The Netherlands. He is managing editor of OSO, Tijdschift voor Surinamistiek, the only scientific journal on Suriname’s History, Literature, Linguistics and Anthropology. He is also managing editor of the Series Bronnen voor de Surinamistiek. He has published a number of books and articles on the Caribbean, especially on Suriname. His Ph-D thesis on the Boni-Maroons of French Guyana was translated into English (1990; The Boni-Maroon Wars in Suriname. Leiden: E.J. Brill). He himself likes most his 1996 publication Het kamp van Broos en Kaliko. De geschiedenis van een Afro-Surinaamse familie. Amsterdam: Prometheus, that will get an English version this year or next year. In collaboration with Okke ten Hove and Heinrich Helstone, he is publishing a series of books on the abolition of slavery in Suriname 1863: Surinaamse Emancipatie. Familienamen en plantages. Amsterdam/Utrecht: Rozenberg Publishers, IBS & CLACS, heeft voor de AVP verschillende politieke functies bekleed en was onder and Surinaamse Emancipatie: Paramaribo: Slaven en Eigenaren. Amsterdam/Utrecht: Rozenberg Publisher, IBS & CLACS.

Dr. Lammert de Jong (1942) served 9 years between 1985 and 1998 as resident representative of the Netherlands government in the Netherlands Antilles. Prior to this he was attached to the University of Zambia and the National Institute of Public Administration in Lusaka, Zambia (1972-1976). In the People’s Republic of Bénin, he was director of the Netherlands Development Aid Organization (1980-1984). He received a PhD in Social Sciences at the Free University, Amsterdam (1972) and published during his academic years about public administration and participation. He concluded his civil service career as Counselor to the Netherlands government on Kingdom Relations. Since then he writes and lectures as a free-lance scholar on post-colonial statehood.

Dr. Dirk Kruijt (1943) is professor of Development Studies at Utrecht University, the Netherlands. Between 1968 and 2003, he alternated between academic teaching and research, and activities as policy advisor to Latin American planning institutes and multilateral and bilateral donor agencies. He was a visiting professor at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) at the University of Sussex, at El Colegio de Mexico, IUPERJ (Rio de Janeiro), the Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, and at the Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO) in Costa Rica, Guatemala, El Salvador and Santiago de Chile. From the mid-1990s on, he evaluated a couple of times the development relations between the Netherlands and the Netherlands Antilles, and the Netherlands and former colony Surinam. His published work is mostly about poverty and informality, war and peace, and military governments. He is the author or co-author of ca. 30 books and ca.100 articles.

Extended Statehood In The Caribbean ~ Paradoxes Of Quasi Colonialism, Local Autonomy And Extended Statehood In The USA, French, Dutch & British Caribbean

2021 – PDF-file of the complete book: https://rozenbergquarterly.com/lammert-de-jong-dirk-kruijt-eds-extended-statehood-in-the-caribbean-paradoxes-of-quasi-colonialism-local-autonomy-and-extended-statehood-in-the-usa-french-dutch-and-british-caribbean/

2008 ~ Quite a number of islands in the Caribbean region have not yet gained independent status. They still have constitutional relationships with former colonial mother countries, be it Puerto Rico with the USA, the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba with the Netherlands, Martinique and Guadeloupe with the French Republic or the Caribbean Overseas Territories with Britain.

The status of the non-independent Caribbean remains ambiguous. None of the islands wish to stand on their own as sovereign states. A range of complexes is attributed to this (quasi) colonial status. They have sacrificed their cultural and political identities for a well-being that – by definition – cannot be fulfilled. The islands’ citizenry suffers from racial discrimination, not only at home, but also on the metropolitan mainland. And instead of exhausting every possibility to achieve sustainable development, a welfare mentality has overwhelmed the dynamics of the islands’ econonomies. Better off, yes, but at what price?

In this book, the islands’ connections with American and European metropolitan centers are considered lifelines which must be strengthened. The constitutional arrangement is defined as extended statehood, a form of government that is meant to supplement the island government. As de-colonization is not an option, it makes no sense to use alternative concepts such as dependency or re-colonization. These terms are biased and outdated. Circumstances have changed and require a format of analysis that goes beyond the old landscape of ‘colonies’ and ‘independent states’. The objective of this book is to promote a new look at extended statehood in the Caribbean while raising a number of questions relating to the operation of the different extended statehood systems across the region. What are their objectives? What is their mission? How are they organized? How do they operate? What are the advantages and what are the disadvantages? Are there any Gordian knots that cannot be solved?

The contributors to this book present a medley of interests in the Caribbean. Jorge Duany and Emilio Pantojas-Garica, University of Puerto Rico, describe the contradictions of Free Associated Statehood in Puerto Rico. Justin Daniel, University of the French Antilles and French Guiana (Martinique), contributed the part on the French Departement d’Outre mer (DOM)(Martinique and Guadeloupe). Peter Clegg, University of the West of England, Bristol, UK, delineates the United Kingdom’s relations with Caribbean Overseas Territories (COT). The chapter on the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Caribbean is by Lammert de Jong, a former resident-representative of the Netherlands in the Netherlands Antilles. Francio Guadeloupe, University of Amsterdam, provided the introduction to anti-national pragmatism. Dirk Kruijt, Utrecht University, assisted in editing the volume.

Extended Statehood In The Caribbean ~ Paradoxes Of Quasi Colonialism, Local Autonomy And Extended Statehood In The USA, French, Dutch & British Caribbean. Lammert de Jong & Dirk Kruijt (Ed.). Rozenberg Publishers, Amsterdam 2005. ISBN 978-9051706864

Table of Contents

1. Lammert de Jong – Extended Statehood in the Caribbean: Definition and Focus.

2. Jorge Duany & Emilio Pantojas-Garcia – Fifty Years of Commonwealth. The Contradictions of Free Associated Statehood in Puerto Rico.

3. Justin Daniel – The French Departements d’outre mer. Guadeloupe and Martinique.

4. Lammert de Jong – The Kingdom of the Netherlands. A Not So Perfect Union with the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba.

5. Peter Clegg – The UK Caribbean Overseas Territories. Extended Statehood and the Process of Policy Convergence.

6. Francio Guadeloupe – Introducing an Anti-National Pragmatist on Saint Martin & Sint Maarten.

7. Lammert de Jong – Comparing Notes on Extended Statehood in the Caribbean.

About the authors

Extended Statehood In The Caribbean ~ Definition And Focus

Introduction

Quite a number of islands in the Caribbean region have not become independent states[i]. They still have constitutional relationships with former mother countries on the European or American mainland, which are commonly designated as dependency relationships. These relationships allow varying degrees of local autonomy and central control. Foreign affairs, international diplomacy and defense are to a large extent taken care of by the European partners or the USA. The islands’ judicial system is in one way or another integrated into the judicial system on the mainland and rules and regulations have to some extent been synchronized. Citizenship rights may have been extended, including metropolitan passports. If so, as USA or European passports holders, the islands’ residents often have unrestricted access to the metropolitan countries.

Caribbean territories that have not become independent nation-states are known under various labels: ‘dependent’, ‘non-independent’, ‘alternative post-colonial’, ‘nonsovereign’, ‘colonies’, ‘protectorates’, ‘subordinated’ or just ‘overseas territories’.[ii] These islands continue to maintain a constitutional arrangement with former colonial motherlands. This constitutional arrangement is defined in this study as extended statehood, a form of government that is meant to supplement the island government. The questions that are dealt with in this book are related to the operations of different extended statehood systems. What is their mission? How do they vary? How are they organized? How do they operate? What are the downsides and bottlenecks, what are the advantages?

Throughout this book the concept of extended statehood systems is applied. The system concept does not imply that extended statehood in the Caribbean is a systematic, well defined, well organized and well coordinated arrangement. It is merely used as a marker to distinguish arrangements between metropolitan countries on the one hand and Caribbean territories on the other: USA – Puerto Rico, the Netherlands – the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba, France – Départements d’outre mer (DOM), and the United Kingdom – Caribbean Overseas Territories. Actually, one of the more significant questions to be raised in this book is how systematic extended statehood in the Caribbean is set up and institutionalized over the last decades.

Alternatives to Independence[iii]

The argument developed in this book is based on the assumption that further decolonization is a non-option. Thus, it makes little sense to qualify the ongoing process of statehood development as a matter of de-colonization or re-colonization.[iv] These terms are biased and outdated; they do not confer a better understanding of the options of extended statehood. References to colonial times and mores do not encourage a new look at statehood development in the Caribbean. Circumstances have changed and require another format of analysis than that found in the old landscape of colonies and independent states. This is not a startling new approach. Already in 1984, a study on the constitutional relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States (of more than 1500 pages) was titled: ‘Breakthrough from Colonialism: an Interdisciplinary study of statehood’.[v] In 1997 a collection of essays was published about ‘rethinking colonialism and nationalism’ with regards to the Estado Libre Asociado of Puerto Rico.[vi] Another study, ‘Islands at the Crossroads’ (2001), calls also for rethinking of politics in the nonindependent territories.[vii] Hintjens wrote in 1995 about alternatives to independence, and in 1997 about the end of independence.[viii] What may be even more telling is that the independence movements on the islands do not attract large followings; their significance is marginal.[ix] For instance, in Puerto Rico.s elections and plebiscites, the percentage for the independence option varied between 19.6% in 1952 to 4.4% in 1993 (in 1964 and 1968 it was a mere 2.8%).[x] A plebiscite in the Netherlands Antilles recorded in 1993/1994 that less than 1% of the voters on the islands of Curaçao, Bonaire, Saba and Sint-Eustatius opted for independence; on Sint-Maarten independence attracted 6.3%.[xi] In a referendum in 2004 14% of the voters on Sint Maarten opted for independence while just less than 5% did that on Curaçao (in 2005). For many a Caribbean scholar and for the large majority ofvoters, independence is no option. Thus the questions to be dealt with are not about independence but rather those that relate to extended statehood arrangements currently in place, how do they work and how can they be put to better use in a highly interactive global world where more and more nation-states have become part of supranational arrangements. Extended statehood will be considered in this study as an arrangement that may prevent these islands from becoming isolated. Read more