Extended Statehood In The Caribbean ~ The French Départements D’Outre Mer. Guadeloupe And Martinique

Introduction

Introduction

In 1946, the French Antilles inaugurated a heterodox process of ‘decolonization through institutional assimilation’. A long historical movement, initiated during the early periods of colonization, made of rupture and discontinuities but sustained by a universalist ambition, found its ultimate consecration in the so-called law of assimilation of 19 March 1946. A new expression – Overseas Department (Département d’outre mer, or DOM) – enriched the juridical-political vocabulary, pointing out both the geographical and historical difference as well as the similarity of political and administrative structures with the Départements of the Metropole. Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Réunion located in the Indian Ocean, and French Guiana situated between Surinam and Brazil in northern South America, became part of the ‘Four Oldest Colonies’. They were integrated within metropolitan France and have been regarded as European territories since 1957.

Départementalisation is another term used to refer to institutional assimilation, while highlighting the unfinished character of the assimilation process. That notion applies not only to institutions, but also to people, from a juridical and a cultural point of view.[i] From a historical perspective, the 1946 départementalisation thus achieves the synthesis contemplated by the reporter of the Constitution of the year III (1795), Boissy d’Anglas,[ii] stemming from a dual question: is it necessary to implant in the ‘Oldest Colonies’, independently from the locally expressed will, an administrative system identical to the current one of the mainland (assimilation of institutions)? Is it necessary to extend to the whole population of these colonies an identical system of values and juridical norms as of the mainland, thereby enlarging the circle of members of the ‘motherland’ (assimilation of people)? Such a colonial doctrine, which originated from the concept of a unified French State, had the tendency to deny all public expression of identity other than its own, and to marginalise all the others for the benefit of citizen allegiance.

Nevertheless, such a claim that so closely associates legal assimilation and cultural assimilation, is a source of many paradoxes that anthropologists have researched for a long time. Supported by an assimilationist ideal in which deep traces of the Ancient Regime are still perceptible, and fed on a universalist claim that the revolutionary heritage continuously reinforced, the colonial project that ensued was no less than a ‘tremendous difference-producing machine’.[iii] The bringing together of peoples from extremely diverse backgrounds to form societies – according to a historical trajectory of a most remarkable nature – was a strong factor in the creation of cultural and social spaces which kept the assimilationist dynamic at bay. It is then indisputable that the French colonial device and the French State had long been resistant to any form of cultural and political autonomy. Nonetheless, these forces emerged and did so without strict alignment to metropolitan norms. Read more

Extended Statehood in the Caribbean ~ Fifty Years of Commonwealth ~ The Contradictions Of Free Associated Statehood in Puerto Rico

July 25, 2002 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Constitution of the commonwealth of Puerto Rico. A Spanish colony until 1898, the Island became an overseas possession of the United States after the Spanish-Cuban-American War. In 1901, the U.S. Supreme Court defined Puerto Rico as an unincorporated territory that was ‘foreign to the United States in a domestic sense’ because it was neither a state of the American union nor a sovereign republic.[i] In 1917, Congress granted U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans, but the Island remained an unincorporated territory of the United States. In 1952, Puerto Ricobecame a Commonwealth or Free Associated State (Estado Libre Asociado, in Spanish).[ii]

July 25, 2002 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Constitution of the commonwealth of Puerto Rico. A Spanish colony until 1898, the Island became an overseas possession of the United States after the Spanish-Cuban-American War. In 1901, the U.S. Supreme Court defined Puerto Rico as an unincorporated territory that was ‘foreign to the United States in a domestic sense’ because it was neither a state of the American union nor a sovereign republic.[i] In 1917, Congress granted U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans, but the Island remained an unincorporated territory of the United States. In 1952, Puerto Ricobecame a Commonwealth or Free Associated State (Estado Libre Asociado, in Spanish).[ii]

The Commonwealth Constitution provides limited self-government in local matters, such as elections, taxation, economic development, education, health, housing, culture, and language. However, the U.S. government retains jurisdiction in most state affairs, including citizenship, immigration, customs, defense, currency, transportation, communications, foreign trade, and diplomacy.

In this chapter, we analyze the socioeconomic costs and benefits of ‘associated free statehood’ in Puerto Rico. To begin, we describe the basic features of the Commonwealth government, emphasizing its subordination to the federal government. Second, we examine the impact of the Island’s political status on citizenship and nationality, which tend to be practically divorced from each other for most Puerto Ricans. Third, we focus on the cultural repercussions of the resettlement of almost half of the Island’s population abroad. Fourth, we review the main economic trends in the half-century since the Commonwealth’s establishment, particularly in employment, poverty, and welfare. Fifth, we recognize the significant educational progress of Puerto Ricans since the 1950s, largely as a result of the government’s investment in human resources. Sixth, we assess the extent of democratic representation, human rights, and legal protection of Puerto Ricans under the current political status. Finally, we identify crime, drug addiction, and corruption as key challenges to any further development of associated statehood in Puerto Rico. Our thesis is that the Estado Libre Asociado has exhausted its capacity to meet the needs and aspirations of the Puerto Rican people, a task that requires a major restructuring of U.S.-Puerto Rico relations.

Over the past decades, the three major political parties – as well as the majority of the Puerto Rican electorate – have expressed a desire to reform Commonwealth status. Major differences of opinion remain regarding how exactly to complete the Island’s decolonization, whether through independence, enhanced autonomy, or full annexation to the United States. Read more

Extended Statehood In The Caribbean ~ The Kingdom Of The Netherlands. A Not So Perfect Union With The Netherlands Antilles And Aruba

Introduction

Het Statuut[i], the Constitution of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, was formalized in 1954 on December 15. It defines the Kingdom as a federal state of three autonomous countries, the Netherlands in Europe and two countries in the Caribbean, the Netherlands Antilles, comprising six islands, and Suriname. In 1975 Suriname left the Kingdom and became an independent country. Aruba, after obtaining a long coveted status aparte in 1986, seceded from the Netherlands Antilles but remained part of the Kingdom as a separate country.

As of December 2004, Het Statuut had lasted half a century, a respectable age. It has weathered the times without changing colour, but now its future seems blurred. At its inception, Het Statuut was not meant to be a constitution that would forever define the domain of a Kingdom of the Netherlands with one part in Europe and another in the Caribbean. From the outset it was believed that one day the Caribbean countries would become independent. For Suriname that day came in 1975. However, for the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba that day may never come. The Antillean public and its political representatives value the current constitutional arrangement of the Kingdom, though with mixed blessings, diverse feelings and complex attitudes. In anticipation of the constitutional anniversary of Het Statuut some uneasiness surfaced, both in the Netherlands as well as overseas. Was it a time of celebration and, if so, how and what to celebrate?[ii] Some authorities were concerned that the anniversary could become a testimonium paupertatis of the operations of the Kingdom in the last 15 years, adding another obstacle to the problematical state of the Caribbean affairs of the Kingdom. In the Dutch press, the Netherlands Antilles were reported as a lost case; a Caribbean democracy that has turned into a Dutch banana republic (sic) in the West Indies.[iii] In April 2004, the Governor of the Netherlands Antilles depicted the crisis his country is experiencing as one of widespread and profound poverty, too many school dropouts with no prospects, increasing drug trade that is derailing civil society, too many murders, muggings and burglaries and a frightening high proportion of criminals.[iv] The number of homicides on Curaçao is staggering and 30 xs higher than in the Netherlands.

The celebrations went ahead, especially in The Hague where on 15 December 2004 the highest officials of all three countries gathered in presence of HM the Queen of the Kingdom. A special coin was issued to commemorate the event.

A Constitution that was not meant for the Caribbean[v]

When the outlines of a post-colonial order were being drawn, at the end of World War II, the Netherlands did not distinguish between its different colonized territories, which included the immense Indonesian archipelago in the East, as well as the small territories in the Latin American hemisphere of Surinam and the Dutch West Indies in the Caribbean. In the process of de-colonization all the territories were simply lumped together. After World War II ended and Japan had capitulated, Indonesia declared itself independent, an act that stunned the Netherlands. The unilateral declaration of Indonesian independence was fought with the sword. Those new to world power, particularly the United States of America, did not agree and eventually forced the Dutch to negotiate with the Indonesian nationalists. The Netherlands attempted to keep Indonesia within the Kingdom by proposing a form of postcolonial federal union. It was thought that a free association of autonomous states could pacify the ambitions of the independence movement. The Indonesian nationalistic powers, however, would not compromise and after four years of war and several round table conferences the government of the Netherlands formally bent to the will of history. The strength and appeal of Indonesia’s independence movement had been misread and could not be

contained within a liberal post-colonial Charter that aimed to keep Indonesia within the Kingdom. Indonesia.s independence marked the end of the Dutch empire.

After Indonesia pulled out of the Kingdom, Surinam and the Netherlands Antilles reaped the fruits of the Netherlands’ attempts to keep Indonesia on board. The West-Indian countries had been party to the Netherlands promise, broadcast on December 6, 1942, by Queen Wilhelmina in exile in London, to de-colonize the Kingdom. The arrangements that were then conceived had not been meant for these much smaller territories. The Caribbean territories, however, would not budge on the concept of a free association of autonomous states as the heir to the colonial Kingdom and stuck to the original liberal terms of the Charter of the Kingdom-to-be. The Caribbean countries claimed autonomy, not independence. They aimed to be partners on equal footing with the Netherlands and succeeded, at least on paper, when in 1954 a new Charter of the Kingdom was enacted. This Charter included the rule that any changes require the unanimous consent of the parties involved. The Netherlands gave in to the aspirations of these small states, believing at the time that there was neither much to gain nor much to lose. The empire was already gone. Moreover, the Charter was not meant for eternity; one day the Caribbean countries would become independent. Read more

Extended Statehood In The Caribbean ~ The UK Caribbean Overseas Territories: Extended Statehood And The Process Of Policy Convergence

Introduction

The chapter analyses the complex and ever-evolving relationship between the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories (formerly known as Dependent Territories) in the Caribbean. The Territories are Anguilla, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Montserrat, and Turks and Caicos Islands. The chapter employs the term extended statehood, which is the focus of this study, in order to illustrate the nature of the relationship between the UK and its Caribbean Overseas Territories (COTs). In particular, there is an evaluation of the effectiveness of the arrangements in place, and a consideration of the extent to which the Territories are actually integrated into the world at large. The links between the UK and its COTs have been shaped and determined by particular historical, constitutional, political and economic trends. For many years the relationship between the COTs and the UK was rather ad hoc – a situation that can be traced back to the compromises, fudges and deals characteristic of pragmatic British colonial administration. The chapter traces the relationship between the UK and its COTs, and the efforts on the part of the current Labour government to overcome the legacy of only sporadic UK government interest, through the imposition of greater coherence across the five Territories via a new partnership based on mutual obligations and responsibilities. It can be argued that the recent reforms have led to a greater convergence of policy across the COTs and a strengthening of Britain’s role in overseeing the activities of the Territories. Nevertheless, problems of governance remain, which have implications for the operation of extended statehood in the COTs, and the balance of power between the UK and the Island administrations. In order to understand the nature of the relationship, it is first necessary to consider the constitutional provisions that underpin it.

The Constitutional Basis of the UK-Caribbean Overseas Territory Relationship

The collapse of the Federation of the West Indies precipitated a period of decolonisation in the English-speaking Caribbean, which began with Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago gaining their independence in 1962, followed by Barbados and Guyana four years later. Despite the trend towards self-rule across the region a number of smaller British Territories, lacking the natural resources of their larger neighbours, were reluctant to follow suit. As a consequence the UK authorities had to establish a new governing framework for them. This was required as the West Indies Federation had been the UK’s preferred method of supervising its Dependent Territories in the region. In its place the UK established constitutions for each of those Territories that retained formal ties with London. The West Indies Act of 1962 (WIA 1962) was approved for this purpose. As Davies states the Act .(…) conferred power upon Her Majesty The Queen to provide for the government of those colonies that at the time of the passing of the Act were included in the Federation, and also for the British Virgin Islands.[i] The WIA 1962 remains today the foremost provision for four of the five COTs. The fifth, Anguilla, was dealt with separately owing to its long-standing association with St Kitts and Nevis.[ii] When Anguilla came under direct British rule in the 1970s and eventually became a separate British Dependent Territory in 1980, the Anguilla Act 1980 (AA 1980) became the principal source of authority.

The constitutions of the Territories framed by WIA 1962 and AA 1980 detail the complex set of arrangements that exist between the UK and its COTs. Because, with the exception of Anguilla, the relationship between the Caribbean Territories and the UK is framed by the same piece of legislation, there are many organisational and administrative similarities. However, there are also a number of crucial differences. Each constitution allocates government responsibilities to the Crown, the Governor and the Overseas Territory, according to the nature of the responsibility. In terms of executive power, authority is vested in Her Majesty the Queen. In reality, however, the office of Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth affairs and the Territory Governors undertake decisions in the Monarch’s name, with the Governors having a large measure of autonomy of action. Despite this, Governors must seek guidance from London when serious issues are involved, and at the level of the Territory they are obliged to consult the local government in respect of matters falling within the scope of their reserved powers. Those powers generally reserved for the Crown include defence and external affairs, as well as responsibility for internal security and the police, international and offshore financial relations, and the public service. strong>[iii] However, some COT constitutions provide Governors with a greater scope for departure when it comes to local consultation. In the British Virgin Islands the Governor is required to consult with the Chief Minister on all matters relating to his reserved powers. While in the Turks and Caicos Islands and the Cayman Islands the Governor is obliged merely to keep the Executive Council informed. With such a balance of authority it has been argued that .the Governor is halfway to being a constitutional monarch (…) taking his own decisions in those areas reserved for him.[iv]. But as Drower has argued .[The Governor] has to have the authority to impose his will, but ability to do so in such a manner, which takes the people with him.[v] Read more

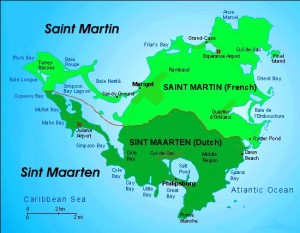

Extended Statehood In The Caribbean ~ Introducing An Anti-National Pragmatist On Saint Martin & Sint Maarten

…the disaster of sovereignty is sufficiently spread out, and sufficiently common, to steal anyone’s innocence. Jean-Luc Nancy (2000: 142)

…the disaster of sovereignty is sufficiently spread out, and sufficiently common, to steal anyone’s innocence. Jean-Luc Nancy (2000: 142)

Much has been written about extraordinary West Indian intellectuals living in the West who see no contradiction in being Caribbean and European, Caribbean and North American. Their strategies of hybridism have become enormously popular in postcolonial studies. Long live the hybrids and blessed are those who follow in their footsteps. They are jettisoned into the position of role models for those who still reside on the islands. If only the islanders would not be so local minded.

What occurs with the best of intentions is that West Indian intellectuals espousing hybridism are presented as cosmopolitans while those who remain on the islands are presented as slaves to localism. Many West Indians myself included prefer that we be seen as pragmatic anti-nationals, and our expressions of being Caribbean and European should be read as such.[i] Our hybridism is not an endorsement for nationalism. It is a manifestation of our disagreement with these and all other imagined communities that harden themselves into natural categories. Categories that seek to assert irreconcilable differences between insiders and outsiders. We complicate notions of exclusive national belonging – asserting our West Indianness, Europeanness, and blackness – in order to awaken others from the nightmare of exclusive nationalism and bio-cultural racism. We are not however blind radicals for we take into account that without the defence of nation-states, at this historical juncture, the vast majority of West Indians would be ravaged by capitalism in WTO ordered world. We temper our principles and seek to listen to those who are reduced to statistics, numbers, and ‘the masses’ by dependency theorists as well as IMF technocrats. This is the stance of pragmatic antinationals, a stance that is a blossoming of a seed planted in us by our West Indian experience.

If there is one general rule among West Indians it is that most of those who stay at ‘home’ and those who go ‘abroad’ are both glocal, and are not totally drunken by nationalism (c.f. Mintz 1996). When and if necessary they can ‘forget’ their national belonging without scaring their souls. It is thus a small step for them to achieve an antinational state of mind. This may be truer on those islands that have never achieved formal independence: the alternative post-colonies in the Caribbean. Wielding Dutch, French, British, and American passports, many visit ‘the mother countries’ frequently and some have spent a few years living in the metropolitan mainland. They are a people who make ample use of the privilege of an extended statehood, and construct a way of being that accords with their situation. On these alternative post-colonies one encounters persons who also have no difficulty being West Indian and European as their counterparts do in ‘the mother countries’. Hybrids, pragmatic anti-nationals, can be found on both sides of the Atlantic. We need a more dynamic understanding of the peoples of the alternative post-colonies of the Caribbean.

The little posed question that this task helps us to answer is why independence activists in the alternative postcolonies have been unsuccessful in amassing huge support for their cause. The pragmatism of these populations who are said to opt out of independence because of a fear of poverty should not be presupposed. It should be proven. Homo economicus and homo ‘pragmaticus‘. need to be produced and stimulated. It is not inborn. We have to understand the mechanisms and human brokers in the cultural realms that continuously promote the pragmatic message countering the anti-Western messages of those championing political independence. In doing so it is of pivotal importance to appreciate the role of media and media personalities. In our mediatic world, media messages determine what we view as reality. Read more

Extended Statehood In The Caribbean ~ Comparing Notes On Extended Statehood In The Caribbean

Great Variety of Extended Statehood

Great Variety of Extended Statehood

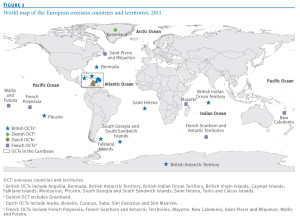

Great diversity is apparent in the organization and day-to-day operations of extended statehood in the Caribbean. Some point out that in the 1990s similarities have been emerging in the three sets of territories that are part of British, Dutch and French extended statehood systems, especially in terms of ‘good governance’ with its focus on democratic politics, competent administration, justice and civil liberties. At the same time it is expected that these territories are likely to retain much diversity in terms of constitutional status, citizenship rights and prospects for independence.[i]

Not only are there wide differences between the European partner countries in the relations they maintain with their overseas territories; also relations between a partner country and its various territories differ. These differences are mainly due to historical factors and to the partner countries’ constitutional structures.[ii] A brief survey of the variations of extended statehood in the Caribbean may serve here as an introduction to a number of issues that spring to the fore when comparing different extended statehood systems.

French Caribbean

Martinique, Guadeloupe and French Guyana have been since 1946 integrated territories in the French Republic; they are French territory, designated as overseas departments (Départments d’outre-mer) (DOM). Strictly speaking, unlike the USA, Dutch and British territories, the DOM have no constitutional links with France since they are part of France itself.[iii] Réno asserts that the most undeniable success of the Assimilation Act is social equality with metropolitan France. The flipside of the legal and political assimilation is, however, blatant economic failure. The state has become the breadwinner.[iv] The integrated status implies that ‘the French state was seen from the outset as the key to development (…) bringing about a new world that would meet every expectation expressed by the local population’.[v] As the DOM are integrated into the institutions of the French Republic, it naturally followed that catching up with the standards of living in France became the norm for the public’s aspirations. The financial transfers from France to the DOM are by and large regular transfers of resources within the French public sector; they do not qualify as assistance or development aid allocations.[vi]

It may be assumed that the public conceives these transfers, perhaps even more so the local politicians, as undisputable rights to provision the DOM public domain. In addition, being part of France implies large funding of the DOM by the European Union. In actuality the European Union provides much more funding to the DOM than France itself. Construction of seaports and airport terminals has been heavily subsidized by the European Union.[vii] Nowadays the currency used in the DOM is the Euro. The inhabitants of the DOM are French citizens with voting rights in the French elections; they have their own representatives in French parliament. The topics these representatives raise in Paris and the way these topics are being dealt with by the French ministers concerned, receive elaborate attention in the local media on the islands; these representatives do count more

than they number.

Dutch Caribbean

The Netherlands Antilles and Aruba are autonomous countries in the Kingdom of the Netherlands with each country having its own parliament, cabinet of ministers as well as local government institutions for each of the five islands of the Netherlands Antilles. These six islands are not integrated parts of the Netherlands in Europe; not the Euro but the Netherlands Antillean Florin (NAF) and the Aruba Florin (AF) is the respective national currency.

In 1954 the Netherlands Antilles and Suriname achieved the status of autonomous states as successor to the former colonial status. The Caribbean countries claimed autonomy, not independence nor integration into the Netherlands. They aimed to be partners on equal footing with the Netherlands. The 1954 Charter of the Kingdom designated the Kingdom as a ‘more or less’ federal state, comprising three autonomous countries, the Netherlands, Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles. Suriname became independent in 1975 with a majority of only one vote in the Surinamese parliament. With the benefit of hindsight, most Dutch politicians today agree that the way Surinam’s independence was handled was not a grand act of post-colonial stewardship. The remaining Dutch Caribbean islands have not wanted to follow Surinam’s example and become independent states. The Netherlands cannot make statehood amendments against the will of the Caribbean countries; the Charter stipulates that any changes require the unanimous consent of the parties involved. Arubans and Netherlands-Antilleans hold Netherlands’ citizenship and passports and have the right of abode in the Netherlands. Aruban and Netherlands-Antillean residents in the Caribbean have no voting rights in the Netherlands elections nor do they have representatives in the Dutch parliament. Unlike the inhabitants of the DOM who feel they belong to ‘Les Français’, the Dutch Antilleans and Arubans consider themselves primordially nationals of their respective island who hold a Netherlands’ passport. Read more