Professional Blindness And Missing The Mark ~ Sexual Slander And The 1965/66 Mass Killings In Indonesia: Political And Methodological Considerations

ABSTRACT. Indonesia has been haunted by the ‘‘spectre of communism’’ since the putsch by military officers on 1 October 1965. That event saw the country’s top brass murdered and the military attributing this putsch to the Communist Party. The genocide that followed was triggered by a campaign of sexual slander. This led to the real coup and the replacement of President Sukarno by General Suharto. Today, accusations about communism continue to play a major role in public life and state control remains shored up by control over women’s bodies.

ABSTRACT. Indonesia has been haunted by the ‘‘spectre of communism’’ since the putsch by military officers on 1 October 1965. That event saw the country’s top brass murdered and the military attributing this putsch to the Communist Party. The genocide that followed was triggered by a campaign of sexual slander. This led to the real coup and the replacement of President Sukarno by General Suharto. Today, accusations about communism continue to play a major role in public life and state control remains shored up by control over women’s bodies.

This article introduces the putsch and the socialist women’s organisation Gerwani, members of which were, at the time, accused of sexual debauchery. The focus is on the question of how Gerwani was portrayed in the aftermath of the putsch and how this affects the contemporary women’s movement.

It is found that women’s political agency has been restricted, being associated with sexual debauchery and social turmoil. State women’s organisations were set up and women’s organisations forced to help build a ‘‘stable’’ society, based on women’s subordination. The more independent women’s groups were afraid to be labelled ‘‘new Gerwani’’ as that would unleash strong state repression. This article assesses the implications of these events for the post-1998 period of Reformasi and reviews some recent analyses of 1965, state terrorism and violence and reveals blind spots in dealing with gender and sexual politics. It is argued that the slander against Gerwani is downplayed in these analyses. In fact, this slander was the spark without which the bloodbath would not have happened and would not have acquired its gruesome significance.

KEY WORDS: Sexual politics, communism, nationalism, Indonesia, women’s movement, gender

In March 2009 campaigning for the parliamentary elections was in full swing.

Nursyahbani Katjasungkana, a popular member of parliament and candidate for the Muslim party Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa (PKB or National Awakening Party), in addition to being a well-known human rights lawyer and feminist activist, was campaigning in the district of Banyuwangi, in East Java, unfamiliar territory for her.[1] Her adversaries mounted a gossip campaign, spreading the rumour that she defended the illegal Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI). The association this allegation was supposed to evoke was that she was an atheist, opposing the clerical elite of the region, fighting for women’s interests and, in general, looking for trouble.

These are serious issues, considering that the PKB is an offshoot of the Nahdlatul Ulema (NU), one of the two largest Muslim organisations in the country. Banyuwangi is considered one of NU’s strongholds, with many Muslim boarding schools (pesantren ) scattered across its vast area. The kyai , leaders of these pesantren , are the backbone of the NU. This was not the first time Nursyahbani Katjasungkana had been associated with the PKI or with one of its mass organisations. In December 1998, six months after the fall of General Suharto, the first national feminist conference since 1965 was held, in Yogyakarta. NKS, as she is popularly known, chaired the conference at which the Indonesian Women’s Congress (Kongres Perempuan Indonesia or KPI) was established. This was the first feminist mass organisation since the destruction of Gerwani . At the time, NKS was accused of being ‘‘Gerwani baru ’’ or a new Gerwani member. That term was reiterated by the then Minister of Women’s Affairs, Tuti Alifiah in a Cabinet meeting in 1999, where she discussed her worries about the establishment of the KPI (NKS, personal communication, April 2009).

Only a few months earlier, when General Suharto was still in power, such an accusation could land one in serious trouble. But even in December 1999, with reformasi proclaimed, mention of Gerwani caused considerable unrest. At the congress, Ibu Sulami, a former secretary of the national leadership of Gerwani, spoke about Gerwani , its history and destruction. This was the first time Ibu Sulami had addressed a public meeting, having been imprisoned for 17 years.[2] Many participants were shocked by what she said, having believed the absurd lies the Suharto regime had spread about Gerwani ’s alleged involvement in the murder of the generals who were killed in the early morning of 1 October 1965.[3] Because of the presence of Ibu Sulami, the delegates of Aisyah , the women’s organisation of the Muhammadiyah, the other large Indonesian Muslim mass organisation, withdrew in protest.

Few events have impacted Indonesian modern history more deeply than the mass murders of 1965/66 which eventually led to the establishment of the New Order under President Suharto. Yet what triggered these mass murders has mostly been hidden under deep layers of fear, guilt, horror and shame. Clearly the trauma of the ‘‘events of 1965,’’ as they are commonly referred to, is still playing an important role in the national imagination. Other than in countries like South Africa, Chile, Cambodia, Argentina and Rwanda, where processes of truth finding have led to some reconciliation, in Indonesia there still has not been a national process aimed at finding truth.[4]

Many issues remain unclear, such as the role Suharto himself played and the extent of the genocide unleashed by the military assisted by religious and, in some cases, conservative nationalist forces. At the local level, some careful efforts at reconciliation are being made by the members of Syarikat Islam (Muslim Association), set up in Yogyakarta in 2003. This process means that young people are being confronted with the mysterious pasts of their parents which have created insurmountable rifts between the families of the killers and of their victims. At the very emotional meeting when Syarikat Islam was launched, members of Ansor , the youth movement of the NU, confessed to having butchered PKI members in 1965. In tears they declared they thought they had been doing the right thing at the time, ‘‘cleansing’’ society from the perceived communist evil. In any case, they said, they had had little choice as they had acted under threat of the military. [5]

The hatred and fear of Gerwani are still so strong that the shooting of Lastri, a film based on a series of interviews with ex-Gerwani members, but with a more romantic fictional story line, was prohibited (Nadia, 2007). Early in 2009, after protests by members of the Surakarta branch of the Front Pembela Islam (FPI or Muslim Defender’s Front) a right-wing Muslim militia group, the mayor of that city forbade Eros Djarot, the director, to shoot the film on location. The arguments used by the FPI were that the film would violate the rights of the Muslim community. The film was seen to be part of a propaganda strategy to create sympathy for communism. A press statement published by the FPI declared further that this was a similar propaganda strategy as the Jews used to enhance sympathy for Israel by stressing the suffering of the many Holocaust victims. The FPI noted that films have a great potential to sway the minds of people, particularly when they contain a love story.

FPI strongly opposed the views of the director that the present beliefs of what happened at Lubang Buaya, the field where the army officers were killed, were just a fairy tale.[6] As will be explained, Gerwani members present when the generals were murdered were falsely accused of sexually torturing them. The film tried to debunk these fabrications. The inhabitants of Karanganyar, where the shooting of the film was to take place, joined the protests and demanded that permission for the filming be withdrawn.[7] Later, students of the Himpunan Mahasiswa Islam Bogor (HMI Bogor or Muslim Students Union) expressed their solidarity with the protesters. Read more

Professional Blindness And Missing The Mark ~ The Anthropologist’s Blind Spots: Clifford Geertz On Class, Killings And Communists In Indonesia

When I first went to Indonesia for research in 1972, I was not well prepared at all. The decision to go to Indonesia had been made at short notice. Soon after I discovered that I would not be allowed to go to Burma, I met Clifford Geertz after he had given a lively seminar at Columbia University and he suggested that I shift my interests to Indonesia. Like many graduate students of this era I had been impressed by Geertz’s Agricultural Involution (1963a). Unlike PhD candidates from universities with strong traditions of teaching and research on Indonesia like Leiden, Wageningen, Amsterdam, Cornell, Berkeley or Yale I had taken no courses in Indonesian studies, knew only a few words of Indonesian language, and had read only a very few books on Indonesia. Among them was a curious and disturbing booklet called Indonesia 1965: The Second Greatest Crime of the Century (Griswold 1970). This booklet gave stark details of the orchestrated anti-Communist backlash after the crushing of a bungled leftist coup attempt in Jakarta (in which twelve persons in total had been killed) and the massacre of hundreds of thousands of alleged communists and communist sympathizers in Java and Bali in late 1965 – early 1966. It also gave a quite different version of the background and course of the massacres than what was to be found in the US Government Printing Office’s semi-official Area Handbook for Indonesia.

When I first went to Indonesia for research in 1972, I was not well prepared at all. The decision to go to Indonesia had been made at short notice. Soon after I discovered that I would not be allowed to go to Burma, I met Clifford Geertz after he had given a lively seminar at Columbia University and he suggested that I shift my interests to Indonesia. Like many graduate students of this era I had been impressed by Geertz’s Agricultural Involution (1963a). Unlike PhD candidates from universities with strong traditions of teaching and research on Indonesia like Leiden, Wageningen, Amsterdam, Cornell, Berkeley or Yale I had taken no courses in Indonesian studies, knew only a few words of Indonesian language, and had read only a very few books on Indonesia. Among them was a curious and disturbing booklet called Indonesia 1965: The Second Greatest Crime of the Century (Griswold 1970). This booklet gave stark details of the orchestrated anti-Communist backlash after the crushing of a bungled leftist coup attempt in Jakarta (in which twelve persons in total had been killed) and the massacre of hundreds of thousands of alleged communists and communist sympathizers in Java and Bali in late 1965 – early 1966. It also gave a quite different version of the background and course of the massacres than what was to be found in the US Government Printing Office’s semi-official Area Handbook for Indonesia.

During my stay in Indonesia I found little to read, and few people willing to talk, about the killings or the events of 1965-66 more generally. In the village in Kulon Progo (Yogyakarta) where I lived during 1972-73 there had been no killings, although people were aware that there had been killings in other parts of the district. On two visits to Jakarta the confident young expatriate staff of the Ford Foundation – always a good source of gossip – seemed to hold to a version of the events of 1965-66 that was close to that of the Area Handbook and the Indonesian government.

When I returned to New York and had decided more or less to make myself into an Indonesia expert, I was of course curious to learn more. One of the first authors I turned to, not surprisingly, was Clifford Geertz. Besides numerous articles and chapters on Indonesian religion and rural society, Geertz had published five books on Indonesia during the years 1960-1968: The Religion of Agricultural Involution, Peddlers and Princes, The Social History of an Indonesian Town, and (after new fieldwork in Morocco in 1963) Islam Observed: Religious Development in Morocco and Indonesia. He had also edited a sixth book, Old Societies and New States (Geertz, 1963c), on politics in the newly-independent countries of Asia and Africa, which included his much-quoted essay ‘The Integrative Revolution: Primordial Sentiments and Civil Politics in the New States’. He was, simply, the world’s best-known authority on post-colonial Indonesian society at the time, and it was hardly possible to discuss any aspect of Indonesian society, culture or politics without reference to Geertz’s work.

Geertz had undertaken long periods of field research in both Kediri (East Java, 1953-4) and Bali (1958), two regions in which the bulk of the killings had occurred and which had been marked by violent political conflicts both before and after his fieldwork.

While his long field visits both took place several years before 1965-66, a few years after the massacres Geertz had the opportunity to revisit both his Balinese and Javanese field research sites. In his Balinese field research village, he learned that the killings had taken place in a single night, when 30 families were burned alive in their houses; in Pare (Kediri) the killings had gone on for about a month (Geertz 1995: 8).

In 1971, while on a consulting mission for the Ford Foundation, Geertz had spent time in social science faculties on several Indonesian university campuses; in some of them as many as one-third of all staff had lost their jobs in the anti-communist purges of 1966-7. During this visit he had also spent time in Jakarta as guest of the Ford Foundation, an agency which, having close connections to the US embassy and the CIA as well as the Indonesian military and cabinet, was well in touch with the emerging facts about the involvement of the US government and the Indonesian army in orchestrating the anti-PKI campaigns of 1965-66.

For all these reasons, Geertz was, at that time, probably as well informed as any foreign scholar about the actors and processes of Indonesia’s massacres, both at national and at local level. Like many others, I expected that Geertz would sooner or later decide to put this knowledge to use in one of the typical, reflective essays for which he had become so famous, to help us understand this extraordinary and dreadful tragedy in Indonesia’s post-colonial experience. So far as I know, however, no such essay exists. In the twenty years that followed the killings Geertz alluded to them in only a few scattered references.

Geertz’s avoidance of any serious discussion of the Indonesian mass murders of 1965–66, and what they mean for our understanding of Indonesian politics, is both puzzling and revealing. This does seem to be a good example of what Wertheim in his later years called the “sociologists’ blind spots”, or the “sociology of ignorance” [Wertheim (1984) (1975)]. One dimension of this, about which Wertheim has written, is Geertz’ chronic blindness to class inequalities in Javanese society. Many young researchers of the 1970s, both Indonesian and foreign, had become convinced that the picture of harmonious, poverty-sharing village communities established in such writings as Agricultural Involution was not right. As Wertheim remarked, Geertz’s vision of rural Javanese society mirrored the blindness of colonial and post-colonial élites, whose idea of the harmonious and homogeneous village community was derived from, and promoted by, the village élite themselves (Wertheim 1975: 177-214; cf. Utrecht 1973: 280). There is certainly a striking lack of fit between Geertz’s accounts of Javanese homogeneous rural and small-town culture and the many violent political conflicts in the region both before and after his fieldwork.

But the few scattered comments on the killings which Geertz did make during these years (and which we will summarize below) suggest also the weaknesses of a reliance on cultural explanations of Indonesian collective political violence. This was the type of explanation prevailing at the time among Western media and semi-popular authors; an outbreak of mass communal frenzy, based on pent-up resentment at the leftists’ undermining of core (Balinese or Javanese) values of harmony and order. In most accounts, the killings burst suddenly on the scene, and then stopped just as suddenly; see for example the accounts of journalist John Hughes (1967), Rand Corporation and CIA author Guy Pauker (1968) or the later memoirs of Marshall Green, who had been US Ambassador in Jakarta at the time of the coup (Green 1990). Read more

Professional Blindness And Missing The Mark – Postscript

In this book we presented six short studies on political crises that occurred during the first two decades of the existence of the Republic of Indonesia. The articles are mainly based on source material that until recently had escaped the attention or had only been analyzed selectively. In all these cases ignorance played a role, resulting either from lack of knowledge or unwillingness to take note of relevant information. From a wider range of possible options, four of the most important causal factors are discussed in the present volume.

In this book we presented six short studies on political crises that occurred during the first two decades of the existence of the Republic of Indonesia. The articles are mainly based on source material that until recently had escaped the attention or had only been analyzed selectively. In all these cases ignorance played a role, resulting either from lack of knowledge or unwillingness to take note of relevant information. From a wider range of possible options, four of the most important causal factors are discussed in the present volume.

The first factor (I) is formed by the policy of governments (and other owners of information) of closing their more sensitive archives and other sources of information for political reasons for a given period. Normally, a way out is offered by the handling of fixed terms and legal facilities such as the US Freedom of Information Act. The researcher may be able to speed up the opening up of the archives he wishes to see by calling on those kinds of acts. Some leeway may be created this way, depending upon the democratic disposition of the authorities in charge, or the sensitivity of the material. When this does not work, we come upon a second and more serious category (II), that is to say the world of secrecy, where the powers that be try to hide their involvement in morally or politically reproachable affairs in the past, or present them in a form more amenable to their actual interests. This brings us to the third category (III), made up of academics and the like that for reasons of opportunity or fixed convictions tend to look away when confronted with evidence that does not fit in with earlier hard won and widely accepted theories. These are found in all walks of academic life. Linked to this, but defined here as a fourth category (IV), are the sentiments of participants in past events, who tend to reject analyses that do not fit their personal memories. Often, journalists can be found in in this same group.

We derived the Ignorance concept from Wertheim’s last Master Course from 1972/1973, when he warned his master students against the neoliberalism that was entering social sciences at the time, by taking the individual as the starting point for the comparative study of society. Although the term neoliberalism has different meanings in different fields of research, Wertheim focused on the neoliberal fixation on the trading individual and its rejection of structuralism in the study of history. He dived into the history of the sociology of knowledge and made students aware of the arguments behind these constructions. He argued that they had been helpful in analyzing the historical roots of social inequality and oppression, and illustrated this with examples from ignorance cases from the history of the Netherlands Indies. In these articles we follow the trail a bit further into the first decades of Indonesian independence.

The early stages of the Indonesian revolution created a multitude of ideologically driven political and military groups, under the umbrella of a president who desperately tried his best to keep the fragments together and provide them with a view of the country in order to unite them under the flag of independence. At the time, Indonesia failed to create a centralized and institutionalized state system. Policy making was a matter of networking, trading and sharing power with activists that claimed imagined institutional positions, as well as manipulating information and managing rumors to mobilize followers and supporters for their aims. After 1950, the political, military and cultural fragments that survived the war against the Dutch continued to wage their own battles. They did so up to 1965 and after. The Cold War context was the framework in which these battles took place. It provided the groups with plenty opportunities to try to get foreign support for domestic action, either threatening the president’s position or supporting it. All crises studied in this book were domestic affairs indeed. Any links of revolutionary movement members to the outside world were of an opportunistic nature, united only by a drive towards independence. They all strived after some form of independence, but it was always one of their own making. The leaders of the 1948 Affair and the initiators from the GK30S had a decidedly different state in mind than the various Papuan concepts of Independence. So there was ample room for disagreement and internal rivalry. President Sukarno in particular excelled at changing partners for the sake of keeping upright the values of Revolution and Independence as he saw fit during the first twenty years of Indonesia’s existence. Read more

The Caribbean Commons

Welcome to the Caribbean Commons blog. Begun as part of the Caribbean Epistemologies Seminar at the CUNY Graduate Center, this blog primarily announces Caribbean Studies CFPs, events, and publications of interest to those in the Northeast US. It also archives information from the CE Seminar. Blog run by Kelly Baker Josephs.

Welcome to the Caribbean Commons blog. Begun as part of the Caribbean Epistemologies Seminar at the CUNY Graduate Center, this blog primarily announces Caribbean Studies CFPs, events, and publications of interest to those in the Northeast US. It also archives information from the CE Seminar. Blog run by Kelly Baker Josephs.

Recent Posts:

- Caribbean History, Journey, Belonging, and Race

- Writer’s Retreat with Mervyn Morris

- Radicalism, Revolution, and Freedom in the Caribbean

- Why Haiti Needs a Higher Love V

- Latin American and Caribbean Philosophy, Theory, and Critique

- Special issue of ArtsEtc honoring Kamau Brathwaite

- Identifying Identity – Ancient Faiths, New Lands

- Simone Leigh: Moulting

- Maroons, Indigenous Peoples, and Indigeneity

Read more: https://caribbean.commons.gc.cuny.edu/

NTR ~ Caribisch Nederland, 3 jaar later ~ Bonaire

19 oktober 2013. Toen Bonaire een bijzondere gemeente van Nederland werd, onstonden er 2 eilanden. Er was het kleine pittoreske Bonaire waar iedereen elkaar kent, en een nieuw snel Bonaire van Nederlandse migranten.

Zie: http://www.uitzendinggemist.net/Caribisch_Nederland

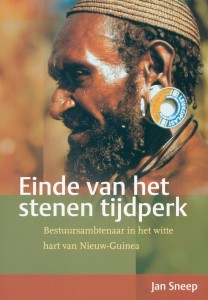

Jan Sneep – Einde van het stenen tijdperk – Bestuursambtenaar in het witte hart van Nieuw-Guinea

Jonge bestuursambtenaren maakten maandenlange verkenningstochten naar een van de laatste nog nooit door blanken betreden delen van het onhergbergzame centrale bergland, het Sterrengebergte in toenmalig Nederlands Nieuw-Guinea. Sneep beschrijft de eerste tochten van zijn collega en vriend Hermans, die een vliegveldje aanlegde en een pioniersbivak bouwde, het begin van de eenvoudige bestuurspost Sibil. Van daaruit trokken zij verder het bergland in en maakten kennis met bewoners in afgelegen valleien die eerst wat schuchter, maar al snel heel nieuwsgierig, vriendelijk en gastvrij de witte mensen in hun dorpen ontvingen.

Jonge bestuursambtenaren maakten maandenlange verkenningstochten naar een van de laatste nog nooit door blanken betreden delen van het onhergbergzame centrale bergland, het Sterrengebergte in toenmalig Nederlands Nieuw-Guinea. Sneep beschrijft de eerste tochten van zijn collega en vriend Hermans, die een vliegveldje aanlegde en een pioniersbivak bouwde, het begin van de eenvoudige bestuurspost Sibil. Van daaruit trokken zij verder het bergland in en maakten kennis met bewoners in afgelegen valleien die eerst wat schuchter, maar al snel heel nieuwsgierig, vriendelijk en gastvrij de witte mensen in hun dorpen ontvingen.

De dragers deden ‘s avonds aan het kampvuur verslag van hun ervaringen van die dag, wat vaak tot hilarische taferelen leidde.

Sneep heeft vervolgens een belangrijk aandeel in de voorbereiding van de laatste grote wetenschappelijke expeditie van het Koninklijk Nederlands Aardrijkskundig Genootschap (KNAG) naar het Sterrengebergte en neemt daar namens het Bestuur gedurende zes maanden ook aan deel. Hij beschrijft zijn ervaringen en de vele problemen waarmee de expeditie te kampen had.

Aansluitend vergezelde Sneep de Frans-Nederlandse filmexpeditie van de cineast Pierre Dominique Gaisseau die in zeven maanden van Zuid- naar Noordkust trok, door goeddeels onbestuurd gebied. Behalve tot dan toe onbekende bergbewoners ontdekten zij ook een Nederlandse pater die zich met zijn Papua geliefde in het geisoleerde oerbos had teruggetrokken. Het boek Einde van het stenen tijdperk is in 2005 bij Rozenberg Publishers verschenen. ISBN 978 90 5170 927 8.

Nu online:

Inleiding

Naar Nieuw-Guinea

Video: Interview Pierre Dominique Gaisseau

Einde van het stenen tijdperk – Mijn eerste standplaats Mindiptana

Einde van het stenen tijdperk – Het Sterrengebergte

Einde van het stenen tijdperk – Mijn tweede standplaats – Sibilvallei

Einde van het stenen tijdperk – De Sterrenberg expeditie

Einde van het stenen tijdperk – De Frans-Nederlandse filmexpeditie

Einde van het stenen tijdperk – Nawoord