ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Preface

At the Fourth Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (ISSA) in June 1998 a great many scholars interested in argumentation assembled in Amsterdam to present papers and exchange views. The ISSA conferences have become an important meetingplace for argumentation theorists stemming from a great variety of academic backgrounds and traditions and representing a wide range of academic disciplines and approaches: philosophy, speech communication, psychology, law, linguistics, rhetoric (classical and modern), logic (formal and informal), critical thinking, discourse analysis, pragmatics, and artificial intelligence. The Proceedings of the conference reflect that diversity.

At the Fourth Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (ISSA) in June 1998 a great many scholars interested in argumentation assembled in Amsterdam to present papers and exchange views. The ISSA conferences have become an important meetingplace for argumentation theorists stemming from a great variety of academic backgrounds and traditions and representing a wide range of academic disciplines and approaches: philosophy, speech communication, psychology, law, linguistics, rhetoric (classical and modern), logic (formal and informal), critical thinking, discourse analysis, pragmatics, and artificial intelligence. The Proceedings of the conference reflect that diversity.

Almost all the papers presented at the conference are published in this Proceedings of the Fourth ISSA Conference on Argumentation. Apart from the hard copy publication, a cd rom version of the proceedings is also made available.

This time the papers are arranged in alphabetical order. In principle, all papers are published exactly as they are handed in by the authors; no further editing has taken place.

The four editors would like to express their gratitude to the Board of the University of Amsterdam, the Faculty of Humanities, the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW), the Dutch Speech Communication Association (VIOT), the Institute for Functional Research of Language and Language Use (IFOTT), the Amsterdam University Association (AUV), the City of Amsterdam, Kluwer Academic Publishing House, and the International Centre for the Study of Argumentation (Sic Sat) for their financial support of the conference and the publication of these Proceedings.

They also want to thank Erik Poolman, Bart Garssen and Willy van der Pol for their assistance.

Frans H. van Eemeren – University of Amsterdam

J. Anthony Blair – University of Windsor

Rob Grootendorst – University of Amsterdam

Charles A. Willard – University of Louisville

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Reconstruction Games: Assessing The Resources For Managing Collective Argumentation In Groupware Technology

Advances in new information technology has brought computerization to bear on practices of argumentation in organizations thus providing a range of new alternatives for improved handling of disputes and decisions (Aakhus, 1997; Baecker, Grudin, Buxton, and Greenburg, 1995; Ngyemyama and Lyytinen, 1997; Nunamaker, Dennis, Valacich, Vogel, and George, 1991; Poole and DeSanctis, 1992). Many of these technologies, called “groupware,” are systems explicitly designed to intervene on discourse and manage it by supplying resources that help communicators overcome obstacles to resolving or managing their disputes and decisions. In designing and deploying groupware, members of the industry practice “normative pragmatics” (van Eemeren, Grootendorst, Jackson, and Jacobs, 1993) since they grapple with the problem of reconciling normative and descriptive insights about disputing and decision- making in order to effectively manage it. In particular, they must deal with a critical puzzle for argumentation theory and practice (and for groupware design). That is, how to develop procedures that further the resolution of a dispute while remaining acceptable to the discussants and that apply to all speech acts performed in order resolve the dispute (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1984, p. 17).

Advances in new information technology has brought computerization to bear on practices of argumentation in organizations thus providing a range of new alternatives for improved handling of disputes and decisions (Aakhus, 1997; Baecker, Grudin, Buxton, and Greenburg, 1995; Ngyemyama and Lyytinen, 1997; Nunamaker, Dennis, Valacich, Vogel, and George, 1991; Poole and DeSanctis, 1992). Many of these technologies, called “groupware,” are systems explicitly designed to intervene on discourse and manage it by supplying resources that help communicators overcome obstacles to resolving or managing their disputes and decisions. In designing and deploying groupware, members of the industry practice “normative pragmatics” (van Eemeren, Grootendorst, Jackson, and Jacobs, 1993) since they grapple with the problem of reconciling normative and descriptive insights about disputing and decision- making in order to effectively manage it. In particular, they must deal with a critical puzzle for argumentation theory and practice (and for groupware design). That is, how to develop procedures that further the resolution of a dispute while remaining acceptable to the discussants and that apply to all speech acts performed in order resolve the dispute (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1984, p. 17).

The purpose here is to show how practical solutions to this analytic puzzle found in groupware reveal implicit theories of argument reconstruction. Implicit theories yet to receive descriptive or critical attention. This is accomplished by conceptualizing groupware products as models of “reconstruction games” that when implemented constitute particular forms of talk through which parties address a dispute or decision.

1. Groupware

Groupware products are designed for a wide range of human activity that involves argument relevant activities such as scheduling, strategic planning, design, group-writing, and negotiation. Groupware is defined by Peter and Trudy Johnson-Lenz as “intentional group processes and procedures to achieve specific purposes plus software tools designed to support and facilitate the group’s work” (Hiltz and Turoff, 1992, p. 69). The enduring novelty of groupware lies in (1) the capacity of the tools to allow large groups of people to come together across time and geographic location and in (2) how the nature of the medium might solve standard problems of collaborative decision-making such as information sharing, cooperative action, authority, and errors of collective judgement (Johansen, 1988; Sproull & Keisler, 1991; Turoff & Hiltz, 1978).

Advances in networked computing are leading to a proliferation of groupware products that are increasingly difficult for users, designers, and researchers to classify, assess, and choose. Indeed, what are groupware products supposed to do? It is generally understood that groupware aids decision relevant communication (DeSanctis & Gallupe, 1987). Yet, existing approaches for classifying and assessing groupware do not adequately address the communicative purposes of groupware design. For instance, the most common way proposed to understand groupware is in terms of how the tool supports interaction across time and geographic location (Johansen, 1988). The trade literature, moreover, focuses on the technical compatibility of groupware products within existing technological infrastructures (Price Waterhouse, 1997). Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Framing Blame And Managing Accountability To Pragma-Dialectical Principles In Congressional Testimony

On July 7, 1987, Marine Lieutenant Colonel Oliver L. North appeared before the Select Committee of the United States Congress investigating the Iran-Contra affair. The name Iran-Contra refers to a two pronged initiative conducted covertly by the National Security Council[i] (NSC) to (a) sell weapon systems to Iran in exchange for the release of Americans taken hostage by fundamentalist Islamic groups in Lebanon, and (b) divert profits from these weapons transaction in support of the Contra rebel resistance movement fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. North served on the staff of the NSC and was the individual widely thought to be responsible for many of the covert activities under investigation by the select committee (Newsweek, January 19, 1987: 17).

On July 7, 1987, Marine Lieutenant Colonel Oliver L. North appeared before the Select Committee of the United States Congress investigating the Iran-Contra affair. The name Iran-Contra refers to a two pronged initiative conducted covertly by the National Security Council[i] (NSC) to (a) sell weapon systems to Iran in exchange for the release of Americans taken hostage by fundamentalist Islamic groups in Lebanon, and (b) divert profits from these weapons transaction in support of the Contra rebel resistance movement fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. North served on the staff of the NSC and was the individual widely thought to be responsible for many of the covert activities under investigation by the select committee (Newsweek, January 19, 1987: 17).

Congressional Hearings have as their ostensible goal the uncovering of “truth.” This occurs in part through unmasking and making public the various acts and activities of individuals and organizations of interest to the American government and people.

This truth oriented goal is identified in the observations provided by two members serving on the Select Committee conducting the Iran-Contra hearings, Congressman Bill McCollum (R-Florida) and Senator Paul S. Sarbanes (D-Maryland). Their commentary occurred on the last day of the initial questioning of North by the attorneys for the Select Committee.

Example A: 324-325

01 McClm: Their job, I thought, in my opinion, whether it’s Senate counsel or House counsel, is to bring out facts, not to give positions, not to slant biases. And I think Mr. Liman has been going through a whole pattern of biased questions today. He has done some of that in the past, but it has been particularly egregious this morning.

04 Sarb: ’And I think the witnesses that come before us come here in order to help us to get at the truth…But, I think Counsel’s questioning has been reasonable and tough, but it’s been within proper parameters… it’s a responsibility of Counsel and of the members of this committee to press the witnesses very hard to find out the truth in this matter.

These remarks in the participant’s own voices highlight several important aspects of congressional hearings. First, the publicly stated goal of such hearings is to bring the facts or “truth” into public view. Second, there are at least two participants who occupy different roles. A questioner presents questions to respondents who provide answers. Participants in the hearing process share the responsibility for getting facts or truth of a matter into the open. With this responsibility comes accountability on the part of each participant to the process. In example A, McCollum asserts the function of the questioner is to uncover facts, the questioners being in this case the legal counsels for the Select Committee who performed the majority of the questioning of Colonel North and other witnesses.

Sarbanes represents the function of the hearings as “to get at the truth.” Witnesses, occupying the role of answerer, participate in order to help uncover the truth. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – The Argument Ad Hominem In An Interactional Perspective

My general contention is that argument ad hominem can be viewed as an integral part of ordinary argumentation, and more specifically, of polemical discussions and debates. Departing from the definition of ad hominem as an informal fallacy, this paper analyzes it as a component of the argumentative interaction between orator, addressee and opponent. It draws on a few contemporary theories stressing the importance of rhetorical interaction rather than of mere logical validity. In this framework, argument ad hominem is examined in relation both to the status and to the image (ethos) of the opponent and of the proponent.

My general contention is that argument ad hominem can be viewed as an integral part of ordinary argumentation, and more specifically, of polemical discussions and debates. Departing from the definition of ad hominem as an informal fallacy, this paper analyzes it as a component of the argumentative interaction between orator, addressee and opponent. It draws on a few contemporary theories stressing the importance of rhetorical interaction rather than of mere logical validity. In this framework, argument ad hominem is examined in relation both to the status and to the image (ethos) of the opponent and of the proponent.

I will try to briefly outline this approach while discussing its main sources, in particular van Eemeren and Grootendorst’s pragma-dialectical treatment of the argument ad hominem, and Brinton’s “ethotic argument”. Theoretical principles will then be exemplified by a case study, namely, Julien Benda’s open letter to Romain Rolland, which is a protest against Rolland’s appeal for understanding and peace during World War I.

Argument ad hominem: a short theoretical survey

As emphasized in historical surveys of the notion (Hamblin 1970,van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1993, Nuchelmans 1993), the expression argument ad hominem refers to various argumentative phenomena that have to be sorted out before proceeding to any further reflection. The main distinction is the one clearly drawn by Gabriel Nuchelmans between arguments ex concessis “based on propositions which have been conceded by the adversary” (1993:38), and proofs or refutation focussing on the person rather than on the matter of the case. In order to avoid confusion, the latter has sometimes been called argumentum ad personam (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca 1970). We shall however stick to the argumentum ad hominem as an argument directed toward the person of the speaker (and not as a premiss admitted by a specific audience).

“According to modern tradition an argument ad hominem is committed when a case is argued not on its merits but by analysing (usually unfavourably) the motives or background of its supporters or opponents” (Hamblin 1970:41). In Copi’s words:

“Whenever the person to whom an argument is directed (the respondent) finds fault with the arguer and concludes that the argument is defective, he or she commits the ad hominem fallacy” (Copi 1992:127).

Roughly speaking, there are three main contemporary approaches to the study of argument ad hominem: logic, pragma-dialectic and rhetoric. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Framing Blame And Managing Accountability To Pragma-Dialectical Principles In Congressional Testimony

On July 7, 1987, Marine Lieutenant Colonel Oliver L. North appeared before the Select Committee of the United States Congress investigating the Iran-Contra affair. The name Iran-Contra refers to a two pronged initiative conducted covertly by the National Security Council[i] (NSC) to (a) sell weapon systems to Iran in exchange for the release of Americans taken hostage by fundamentalist Islamic groups in Lebanon, and (b) divert profits from these weapons transaction in support of the Contra rebel resistance movement fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. North served on the staff of the NSC and was the individual widely thought to be responsible for many of the covert activities under investigation by the select committee (Newsweek, January 19, 1987: 17).

On July 7, 1987, Marine Lieutenant Colonel Oliver L. North appeared before the Select Committee of the United States Congress investigating the Iran-Contra affair. The name Iran-Contra refers to a two pronged initiative conducted covertly by the National Security Council[i] (NSC) to (a) sell weapon systems to Iran in exchange for the release of Americans taken hostage by fundamentalist Islamic groups in Lebanon, and (b) divert profits from these weapons transaction in support of the Contra rebel resistance movement fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. North served on the staff of the NSC and was the individual widely thought to be responsible for many of the covert activities under investigation by the select committee (Newsweek, January 19, 1987: 17).

Congressional Hearings have as their ostensible goal the uncovering of “truth.” This occurs in part through unmasking and making public the various acts and activities of individuals and organizations of interest to the American government and people.

This truth oriented goal is identified in the observations provided by two members serving on the Select Committee conducting the Iran-Contra hearings, Congressman Bill McCollum (R-Florida) and Senator Paul S. Sarbanes (D-Maryland). Their commentary occurred on the last day of the initial questioning of North by the attorneys for the Select Committee.

[Example A: 324-325]

01 McClm: Their job, I thought, in my opinion, whether it’s Senate counsel or House counsel, is to bring out facts, not to give positions, not to slant biases. And I think Mr. Liman has been going through a whole pattern of biased questions today. He has done some of that in the past, but it has been particularly egregious this morning.

04 Sarb’ And I think the witnesses that come before us come here in order to help us to get at the truth… But, I think Counsel’s questioning has been reasonable and tough, but it’s been within proper parameters… it’s a responsibility of Counsel and of the members of this committee to press the witnesses very hard to find out the truth in this matter. Read more

ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Refuting Counter-Arguments In Written Essays

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Many discourse analysts and rhetoricians have noted that one valued basis for argumentation, and academic argumentation, in particular, is contrast, that is, setting out opposition (Barton 1993; 1995; Peck MacDonald 1987).

The aim of this paper is to look more closely into one specific type of contrast and describe its structures and usage. The contrast I have in mind is the refutation of counter-arguments, defined as arguments (i. e., reasons) in favor of the standpoint (the conclusion) opposite to writer’s own standpoint. In order to see how writers actually refute counterarguments, I chose a book called Debating Affirmative Action: Race Gender, Ethnicity, and the Politics of Inclusion, edited by Nicolaus Mills 1994. The book is mostly a collection of argumentative texts by academic scholars, which debate a well defined issue, and clearly and unequivocally pronounce themselves most of the time either pro or con affirmative action. In less than 200 pages (not all the 307 pages of the book are argumentative texts), about 130 counter-argument refutations have been found. These texts are enough to give us a good idea about the most popular ways of refuting counter-arguments in written texts when debating controversial political or social issues in an academic milieu.

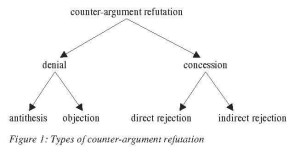

A counter-argument can be refuted in two possible ways:

1. by denying the truthfulness or the acceptability of the propositional content of the counter-argument, thereby denying its value as counterargument;

2. by accepting the truthfulness of the propositional content of the counter-argument, but, nevertheless, rejecting the opposite standpoint and therefore denying the relevancy or the sufficiency of the proposition to serve as counter-argument. The first type will be called denial, the second concession (see Perelman 1969: 489; Henkemans 1992: 143-153).

Two subtypes of denial have been discerned:

1. when the denied proposition is replaced by another, which serves as a pro-argument, or is argumentatively neutral;

2. when the denied proposition is not replaced by another. The first subtype will be called antithesis (the proposition that has been denied is the ‘thesis’, and the one replacing it is the ‘antithesis’), the second objection.

Concession also has been classified into two sub-types:

1. when the rejection of the opposite standpoint is directly made and in plain words (direct-rejection concession);

2. when it is only implied (indirect-rejection concession) (see also Azar 1997). Figure 1 summarizes this classification:

We will see now in further detail, together with examples, the four subtypes of Counter-argument refutation.

2. Antithesis

Antithesis is by definition a two-part structure, one expressing explicit denial of a proposition (in our case it is the denial of the counterargument) the other expressing an assertion (in our case it serves as a pro-argument) In our limited corpus, one can find that the denial part of the antithesis always precedes the other part. Only few example have been found, i. e.,

1. Far from preventing another Mount Pleasant (a Washington DC neighborhood where a three- day riot was sparked when a black policeman shot a Salvadoran man – M.A.), affirmative action might actually provoke one (p. 178).

The linguistic devices expressing antithesis consist of many forms. In our example it is far from … actually … .The more usual expression, not … but …, has not been found in our corpus as expressing antithesis; instead, we find: not X Y; not X Rather Y; X Such is the silliness … Y. Read more