Extended Statehood In The Caribbean ~ Introducing An Anti-National Pragmatist On Saint Martin & Sint Maarten

No comments yet …the disaster of sovereignty is sufficiently spread out, and sufficiently common, to steal anyone’s innocence. Jean-Luc Nancy (2000: 142)

…the disaster of sovereignty is sufficiently spread out, and sufficiently common, to steal anyone’s innocence. Jean-Luc Nancy (2000: 142)

Much has been written about extraordinary West Indian intellectuals living in the West who see no contradiction in being Caribbean and European, Caribbean and North American. Their strategies of hybridism have become enormously popular in postcolonial studies. Long live the hybrids and blessed are those who follow in their footsteps. They are jettisoned into the position of role models for those who still reside on the islands. If only the islanders would not be so local minded.

What occurs with the best of intentions is that West Indian intellectuals espousing hybridism are presented as cosmopolitans while those who remain on the islands are presented as slaves to localism. Many West Indians myself included prefer that we be seen as pragmatic anti-nationals, and our expressions of being Caribbean and European should be read as such.[i] Our hybridism is not an endorsement for nationalism. It is a manifestation of our disagreement with these and all other imagined communities that harden themselves into natural categories. Categories that seek to assert irreconcilable differences between insiders and outsiders. We complicate notions of exclusive national belonging – asserting our West Indianness, Europeanness, and blackness – in order to awaken others from the nightmare of exclusive nationalism and bio-cultural racism. We are not however blind radicals for we take into account that without the defence of nation-states, at this historical juncture, the vast majority of West Indians would be ravaged by capitalism in WTO ordered world. We temper our principles and seek to listen to those who are reduced to statistics, numbers, and ‘the masses’ by dependency theorists as well as IMF technocrats. This is the stance of pragmatic antinationals, a stance that is a blossoming of a seed planted in us by our West Indian experience.

If there is one general rule among West Indians it is that most of those who stay at ‘home’ and those who go ‘abroad’ are both glocal, and are not totally drunken by nationalism (c.f. Mintz 1996). When and if necessary they can ‘forget’ their national belonging without scaring their souls. It is thus a small step for them to achieve an antinational state of mind. This may be truer on those islands that have never achieved formal independence: the alternative post-colonies in the Caribbean. Wielding Dutch, French, British, and American passports, many visit ‘the mother countries’ frequently and some have spent a few years living in the metropolitan mainland. They are a people who make ample use of the privilege of an extended statehood, and construct a way of being that accords with their situation. On these alternative post-colonies one encounters persons who also have no difficulty being West Indian and European as their counterparts do in ‘the mother countries’. Hybrids, pragmatic anti-nationals, can be found on both sides of the Atlantic. We need a more dynamic understanding of the peoples of the alternative post-colonies of the Caribbean.

The little posed question that this task helps us to answer is why independence activists in the alternative postcolonies have been unsuccessful in amassing huge support for their cause. The pragmatism of these populations who are said to opt out of independence because of a fear of poverty should not be presupposed. It should be proven. Homo economicus and homo ‘pragmaticus‘. need to be produced and stimulated. It is not inborn. We have to understand the mechanisms and human brokers in the cultural realms that continuously promote the pragmatic message countering the anti-Western messages of those championing political independence. In doing so it is of pivotal importance to appreciate the role of media and media personalities. In our mediatic world, media messages determine what we view as reality.

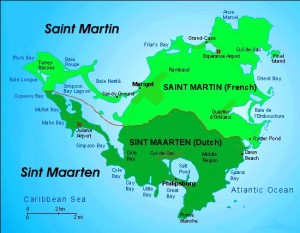

This essay seeks to do exactly this by presenting the philosophy of life of DJ Shadow, a pragmatic anti-national and one of the most popular radio disc jockeys on Saint Martin & Sint Maarten (a bi-national French and Dutch West Indian island), who uses his talents to encourage both newcomers and locals not to believe in nationalism.[ii] On Saint Martin & Sint Maarten (SXM) newcomers have a demographic, economic, and political advantage. 70 to 80% of the 70.000 SXMers are immigrants. Without these newcomers the island cannot cater to the 1 million tourists that visit the island annually. The upper class newcomers hail primarily from the US, Canada, Western Europe, India, and China. They are the major investors and brokers of overseas financiers. The working classes on the other hand – those who ensure Western tourists have an unforgettable vacation – are for the most part West Indians, Latin Americans, and Asians. The autochthons, known as the ‘locals’ have a virtual monopoly in the civil service and occupy the middle management positions. To be considered a local one needs to have ancestral ties that go back at least three generations. Nonetheless while this categorization excludes newcomers, most locals do not express this privilege. They are welcoming to newcomers and do not practice endogamy.

Due to this open stance ‘locals’ have managed to remain in political power. All elected officials are ‘locals’ and most newcomers I spoke to felt that they did not discriminate. The newcomers refuse however to vote for the independistas, fringe politicians who seek laws that will privilege ‘locals’ and champion independence from France and the Netherlands. Especially the working class newcomers are fervently against these measures. They claim that independence in their countries have only made the rich richer and has secured the middle classes as rising bourgeoisie. On SXM they do not live in abject poverty and can remit to love ones in their ‘home countries’. The ‘locals’ and wealthy newcomers also do not vote for independistas for fear of losing their investments and comfortable life.

DJ Shadow feeds this sentiment. Without mentioning their names, he presents the small but vocal group of independence activists as rabble-rousers that wish to create divisions among the various ethnic groups that inhabit the island. Everyday they are bashed for their alleged hypocrisy and ridiculed for being non-pragmatic thinkers. The public who tunes into DJ Shadow’s program, a considerable cross section of the population, are harkened not to believe in the exclusive nationalism forwarded by fringe politicians.

There is an ideological reason behind DJ Shadow’s dislike for nationalism. Being an avid traveller and having resided in Curaçao, the Dominican Republic, the US, Spain, Germany, and the Netherlands, has taught him that all forms of nationalism exclude outsiders. Moreover discrimination of ethnic minorities and ethnic strife are structural. Nationalism for him is anti-humanist. Nonetheless he champions that in order to secure their livelihood, SXMers should opt to remain part of the French Republic and the Dutch Kingdom. In doing so they should not however believe in national exclusivity. It should be a pragmatic decision.

DJ Shadow dismisses protestations of independistas concerning SXMers selling their soul for a few loaves of bread and thereby loosing their dignity. Besides the pragmatic reasons he puts forth as to why SXMers should not opt out of the French Republic and the Dutch Kingdom, he also promotes his own version of a planetary humanism which he labels Rastafari individuality. Five days a week from 13.00 to 17.00 hours, the Shadow claims that all human beings consist of a relatively autonomous Self and a personal God and Devil, which seek to direct their lives. Our task in life is to balance our personal God and Devil, since none of us will ever be able to rid ourselves from the influences of either. DJ Shadow averred that one needed to use the precepts of both to survive in everyday life. According to him this Rastafari individuality offered SXMers a way of being that transcended ethnic differences, and encouraged them to see the underlying unity of human beings. He had learnt to view himself as such by combining Rastafari with the wisdom of his deceased grandmother.

My grandmother was a women who could do things, you know what I mean? She was into her Higher Science [ this is the name given to spiritual philosophies such as Santeria and Montamentu]. I can remember sitting in her lap and she telling me that I should never forget that the Devil used to be an angel too, so he ain’t all that bad. She used to tell me that when you read your Bible and they say that Lucifer was cast down to earth for disobeying God you must remember that it was about power. God had all the power and Lucifer wanted some of it. So they fight and God’s general, Michael, defeat Lucifer and banish him to earth. She would say just like how the big men does fight for power over the heads of the small man, the same thing took place in Heaven. In the same way we too have a God and a Devil inside fighting to have power over we. Both of them want we soul. Now what is important for me is this life, and not so much the other life. Nobody ever come back to tell me how it was. So what I believe we must do is respect both of them and use them to get ahead. But we must always remember that we will never be able to fully control them. So when I say ‘I and I’ sometimes it means me and my God but if you’re fucking around it means me and my Devil ain’t going take your shit. This is my version of ‘I and I’, my Rastafarian individuality, you overs?

While heavily infused with Catholic, Rastafari, and Afro-Caribbean spiritual tenets, the Shadow claimed that his philosophy of life was ecumenical. He phrased the matter thus emphasizing the radical egalitarianism he stood for,

Remember this Star, this what my grandmother, rest her soul, used to say there is no religion in righteousness, religion is a way towards righteousness. You overs? ‘I and I’ want to burn the fear out of the people. A man who afraid to choose for himself is a man who fear life. People have to realize that life is good and Jah give us a compass so we can decide for ourselves. You don’t need anybody telling you what to do and which way to follow. You see for me the pastor and the politician are twins. Pastors I relate to the past. That was when Man used to follow prophets. Old Testament style, seen? Now Man knows better so automatically I and I blocking it out. And politicians is just pollution Star [my cosmic friend], polluting the people brains. We can’t deal with pollution or with the past. They both should have no meaning in this present time here.

I had the opportunity to conduct an in-depth interview with him in 2002 concerning his life experiences and how he became a pragmatic anti-nationalist.[iii] What follows is a thick description of this encounter. Herein I will discuss relevant theories on nationalism and anti-nationalism that substantiate the philosophies of this pragmatic anti-nationalist.

Talking about Nationalism

As I sat in his uncle radio station, PJD2, the station most SXMers tune into, ready to interview him, I couldn’t help thinking that fate deals some people better cards than others. DJ Shadow was a popular radio disc jockey, MC, and singer. His fan base consisted of teenagers and SXMers in their middle years. Moreover he belonged to one of the wealthiest and respected families on the island. His family owed several businesses on the island as well as on neighbouring tourist paradises such as Saint Christopher and Nevis. Besides disc jockeying he dabbled in the family’s business and organized largescale concerts and festivals on the island.

Having been successful in most of his endeavours, the Shadow had a new mission in life and that was encouraging his fellow SXMers not to delude themselves into believing that the naturally belonged to any imagined national community. An excessive belief in nationalism was according to him a symptom of being out of balance, a manifestation of the ‘screwed’ idea of feeling superior to another.

That nation business is just hate business, Devil works. Whenever you have a nation, you have an enemy, you have war. Is like that because you going to believe you better than the other man. I mean Bob Marley spoke about this. Listen to ‘War’, there the man is basically telling you that that is nonsense. Madness B [B is a shortened version of brother]. Jah create us all, that nation business is just tribalism. The illusions of the politricksians [a combination of politician and trickster].

What both DJ Shadow and Marley’s song ‘War’ critique is ‘the imagined community of the nation’ a social construct born in the Americas (c.f. Anderson 1991). According to Anderson the social discrimination directed at the Euro-Creole elites by their metropolitan counterparts combined with travel and the proliferation of printed journals dedicated to primarily local topics led them as a public to imagine themselves as members of a ‘community’ separate from the colonial powers (ibid). As they fought successful wars of independence against their respective ‘mother countries’, they established the first nation-states in the world.[iv] These became the universal models. Several Caribbeanists have challenged Anderson, suggesting that nationalism was not solely fathomed by Euro Creole elites (e.g. Sanchez 2004, Hallward 2004, Trouillot 1990, and James 1969). Nationalism was instead the product of masters and slaves, as well as those belonging to every other social category in between these two extremes. The case of Haiti, which was the wealthiest colony in the New World, when it began its struggle for independence and which became the second nation-state in the world, stands as irrefutable proof. Nationalism and nation-states should also be seen as being related to the rise of liberal egalitarianism, the ideology of Unity and Equality of Man. A circumvention of that noble ideal.

In order to stay competitive in the world markets, however, the leaders of these new nation-states, who were mostly wealthy Euro Creoles, but also sometimes Black planters retained institutions such as slavery, encomienda, and indentured labor, even while proclaiming the Unity of Man. There was also the necessary racism and ethnic discrimination. The latter two ingredients in the construction of nationalism were not an aberration, as several studies have shown that despite the passing of time, and its many incarnations, racism and ethnic discrimination remain integral in most, if not all, official expressions of nationalism and nation-state projects (Mulhern 2002, Brown 2000, Baumann 1999, Gilroy 2000, Kristeva 1991).[v] Black Dutchmen are still an oddity in the minds of many despite the fact that the majority of the Dutch West Indians are brown skinned. The same goes for African countries such as Zimbabwe whereby Whites are still considered ‘honorary insiders’. All nations are characterized by their ethnic and racialist views concerning the character of the chosen and the excluded (ibid).

This insider versus outsider logic also plays itself out among dominant and subordinate groups within a nation. In discussions concerning the issue of national belonging, the ethnic and racial basis of official nationalism is usually camouflaged in the form of civic nationalism – which is ideally based upon voluntarism and ethnical neutrality – and multicultural nationalism – which claims that one should respect the rights of all ‘ethno-racial’ groups or nations within the larger Nation. Under the guise of neutrality (civic) or respect for difference (multicultural), elites among the dominant ‘ethno-racial’ group still decide what constitutes difference and how this should be classified, accepted, and judged.[vi] The latter is what DJ Shadow accused the ‘local’ politicians of doing. As DJ Shadow put it,

I am not for more political autonomy from Holland. That to me is just more nationalism. I think the world has had enough of that. I and I am not endorsing that tribalism.

Relying on his own experiences, DJ Shadow arrived at similar conclusions as scholars who have critiqued the concept of nationalism.

I don’t have to go to school to see that that is nonsense. All I have to do is look at the next man and I know that he ain’t so different from me. He too got to shit, eat, and sleep (followed by a laughter). Any man who can’t see that have to get his head checked.

While print and travel might have encouraged his elite Euro Creole predecessors to imagine nationalism and nation-states as natural communities, Conscious Reggae and travel had led him to realize the inverse. Like them he held grudges against the ‘mother countries’ in Western Europe, but unlike them he was not championing equality and independence while legitimating the subjugation of the poor and the disenfranchised. In a world in which the masses in the politically independent Global South were suffering from the adverse effects of capitalism, he felt nationalist projects and independence movements promised little or no material benefits.[vii]

Traveling as an Awakening: Discoveries in the Americas

DJ Shadow was well traveled, having resided on various Caribbean islands, in the US, and several countries in Western Europe. All these places had been spaces of awakening for him, spaces that led him to understand that nationalism and related hierarchical ideas of belonging engendered violent divisions among human beings. Instead of employing the mutually exclusive categories ‘local’ and newcomer to designate differential and hierarchical belonging, DJ Shadow felt all SXMers should better understand themselves as ‘Rastafari individuals’, and be aware of the violence committed by those who saw themselves as belonging to distinct nations.

DJ Shadow had lived in Curaçao, the Dominican Republic, Saint Christopher, Jamaica, and Trinidad. His stay on these islands strengthened his understanding that SXMers shared many similarities with other West Indians, especially in regard to everyday practices. The islanders borrowed each other’s Creolized cultural products and on each island made something unique of their mutual borrowings. This was especially true in the realm of music. For instance with Calypso music he observed a changing repetition on every island of this genre, which had first emerged in Trinidad. He asserted that in this borrowing there was not only the intention of mimicking but also about proclaiming difference.

Calypso comes from Trinidad but everybody plays it differently. If you give each Caribbean island the same song to play, each one will intentionally play it different. So SXM Calypso is from SXM.

He also pointed out Calypso musicians in Trinidad borrowing from other islands, making the whole origin story problematic.

I mean when you look at it, Trinidadian Calypso get influence by the Jam band style from Dominica, so what is what?

According to him, one could make the same point as far as Conscious Reggae was concerned. What was important as well was that Conscious Reggae composers wrote songs that promoted transnational alliances among the structurally oppressed, primarily dark skinned West Indians, to keep struggling for social justice. While Marley and other Reggae artists had championed national independence in songs such as ‘Zimbabwe’, DJ Shadow consciously omitted this to make his point of transnational solidarity.[viii]

Conciousness don’t cater for that national thing. Marley, Tosh, Burning Spear, Buju, them man is not national them man is international. It is about the black man redemption, about the small man struggles, you overs? The small man in the Caribbean, and let we be frank, most of them black, struggling ever-since with Babylon. But still they ain’t give up yet, they still smiling, and that is their strength. So when Bob say ‘lively up yourself and don’t be no dread’ he telling them remain happy don’t let Babylon enslave you brain. A sad man is a man who lose the battle before it even started.

According to DJ Shadow nationalism sought to obfuscate this and other commonalities among the inhabitants of the Caribbean basin. Caribbean people were as he put it ‘children of the sun‘ . ‘Caribbeaness is defined by the sun‘. He used the term sun in a metaphorical sense. For DJ Shadow the term signified a stance in life that radically asserted joy coupled with an uncompromising sense of somebody-ness and an unrelenting ambition to get ahead.

Caribbean people have an aura about them. They love to party. Bacchanal is their thing. They have a strong sense of pride and don’t accept injustice. They don’ want to sit in the back of the bus [this is an allusion to the Rosa Parks incident that hailed Martin Luther King’s involvement in the Civil Rights movement]. They want front seat, you overs? We SXMers are no exception.

When I asked him where these attributes came from he replied matter-of-factly that they stemmed from the African, Asian, and European ancestors of Caribbean people. However, as with his metaphor of the bus, he explicitly highlighted the experience of Blacks in the New World.

Listen star we don’t have to travel to really know Africa, Europe, or Asia because they are here. We born from them. All of us have to acknowledge our black grandmothers even the whitest of us. If it wasn’t for her titty’s, Star think about it, you overs? [titty’s is a Creole word for tits. DJ Shadow was alluding to the role played by many African women in breastfeeding blacks and whites]. If she didn’t survive none of us would have survived.

DJ Shadow was doing two things in the context of our conversation. He was employing the stereotypes of the eternally joyful and the ambitious West Indians to show me the self-resilience of most Caribbean people who constructed themselves in the midst of unspeakable horrors. By claiming that Africa, Asia, and Europe were in the Caribbean and that all had to acknowledge their black grandmothers, he was referring to the legacy left by the fore-parents and the importance of those who survived slavery. He was voicing that he realized what Caribbeanists have termed ‘the shipwreck experience’ that bind the West Indies and ‘the presences’ that roam about in the region (Walcott 1993, Hall 1992).

The shipwreck experience is a metaphor used to convey the well-documented facts of the horrors of colonialization in the Caribbean. Millions of people from Africa, Asia, and to a lesser extent Europe were forced to leave their prior living environments. Millions were transported to the Caribbean basin on ships chained together by their ankles, strangled by indentured labor contracts, or escaping religious prosecution (Mintz 1996, Walcott 1993). They became the inhabitants of islands whose indigenous population had been all but wiped out. Most of the identifications and practices that they were accustomed to performing were unsustainable in their new homelands, because most of the institutions and contexts upon which they were based were non-existent.

The transplanted peoples of the Caribbean had to be homogenized in some ways to meet the economic demands imposed upon them, at the same time that they were being individualized by the erasure of the institutional underpinnings of their pasts. These were the achievements – if we choose to call them that – of Caribbean colonialism. The movements of people by which such sweeping changes were facilitated were massive, mostly coerced, and extended over centuries. I do not think that there is much with which they can be compared, in previous and subsequent world history. Those who came in chains could bring little with them. The conditions under which they had then to create and recreate institutions for their own use was unimaginably taxing. This was, of course, particularly the situation of those who came as slaves. It was different, and somewhat better, for impressed or contracted Europeans. But the Irish deported by Cromwell, the convicts and the engages, the debt and the indentured servants from Britain and France, cannot be said to have been truly better off, so far as the

transfer of kin groups, community norms or material culture are concerned. Nor for that matter, were the Chinese who would be shipped to Cuba, the Indians who went to the Guianas and Trinidad, or the Javanese who went to Suriname in the subsequent centuries.(Mintz 1996: 297-298)

This has led to the situation that in the Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Arawak and the Carib world are ‘presences’, traces of the old, transformed though nevertheless discernible and lingering in all cultural expressions. Particularly the African presence, though often repressed, remains an important structuring element. During our conversation, DJ Shadow was highlighting its importance. Scholars such as Stuart Hall (1992) and Derek Walcott (1974) have also averred that this structuring element has to be recognized throughout the Caribbean.

‘Presence Africaine’ is the site of the repressed. Apparently silenced beyond memory by the power of the new cultures of slavery, it was, in fact, present everywhere: in the everyday life and customs of the slave quarters, in the languages and patois of the plantations, in the names and words, often disconnected from their taxonomies, in the secret syntactical structures through which other languages were spoken, in the stories and tales told to children, in religious practices and beliefs, in the spiritual life, in the arts, crafts, musics, and rhythms of slave and post-emancipation society. Africa, the signified which could not be represented, remained the unspoken, unspeakable ‘presence’ in Caribbean culture. It is in ‘hiding’ behind every verbal inflection, every narrative twist of Caribbean cultural life. It is the secret code with which every Western text was ‘re-read’. This was–is–the ‘Africa’ that is still alive and well in the diaspora…. Everyone in the Caribbean, of whatever ethnic background, must sooner or later come to terms with this African Presence. Black, brown, mulatto, white–all must look ‘Presence Africaine’ in the face, speak its name’. (Hall 1992: 229-230)

While ‘African traces’ are of utmost importance, and despite the progress made due to the growing black consciousness in the region they are still not sufficiently recognized, contemporary Caribbean people and their cultural expressions are an embodiment of all the ‘presences’ in constant reconfiguration. All ‘traces’ play a constitutive role and ‘racial’ taxonomies offer no privileged indication of the different Caribbean groups or their

cultural expressions. In telling fashion Édouard Glissant forecloses any possibility of arguing that although Caribbean people and their expressions are in the making, in a state of becoming as Stuart Hall would phrase it, one could nevertheless claim to discern groups based on ‘racial’ criteria’s or singular roots.

‘…whatever the value of the explanations or the publicity Alex Haley afforded us with Roots, we have a strong sense that the overly certain affiliation invoked there does not really suit the vivid genius of our countries’. (Glissant 2000: 72).

Several other studies have shown that these reconfigurations were done and continue to be done in a milieu characterized by colonial, neocolonial, and internally based structural inequalities. Phrased differently, in a world dominated by Western powers that still have difficulties admitting that racism and capitalist exploitation are the foundation of their polities (e.g. Palmié 2002, Besson 2002, Sheller 2000).[ix] Especially for the working classes, recreating themselves positively and struggling against these structural inequalities went hand in hand.

The ‘presences’, reconfigured into Caribbean cultural expressions and enmeshed in projects dedicated to social justice, also gave birth to xenophobic nationalist projects and hierarchical ideas of belonging. DJ Shadow personally experienced xenophobia and at the hands of ‘autochthon’ elite and working class Curaçaoleans when he attended secondary school on Curaçao.

When you left here as a young man and you go to school in Curaçao, MAVO and HAVO (high school), back in the day they would call you an Ingles Stinki (uncouth Englishmen), tell you ain’t got no culture. And I am an Antillean just like you B. I carrying the same passport you carrying. I don’t have anything against them personally but that mentality has got to go. They feel that Curaçao is the head, Curaçao is number one, like they would say Yu di Korsow (literally: son of the Curaçao), and consider themselves better than everyone. No one is better than another. Jah ain’t create nations, seen. Too much of them under the spell of they politricksians who robbing them while the eyes open.

This experience of DJ Shadow and other Dutch Windward island students who spoke primarily English being called ‘Ingles Stinki’, uncouth Englishmen, is a telling example of the adverse effects of the presences reconfigured in the ethnic biases of Curaçaolean nationalism. It is an example in which the ‘presence Europeéanne’ is clearly discernible, or in DJ Shadow’s terms, ‘the Western sensibility driving them mad’. Let me clarify this. If one unclogs one’s mind from ‘race’, one realizes that what these predominantly dark skinned Curaçaoleans were doing in calling their Windward island counterparts uncouth Englishmen was a trace of the historical opposition that Western European thinkers, in the late 19th and early 20th century, posited between Roman speaking Europeans and those who spoke Germanic languages. These linguistic differences sometimes combined with assertions of Catholicism versus Protestantism and distinct ‘cultures’ were used to make and substantiate ethnic and racist claims (c.f. Skurski, 1997, Rojas & Matta 1997, Rock, 1987). French and Spanish thinkers posited that Latin Europeans were more high cultured and Catholicism a more spiritual religion than the Protestantism of Northern Europeans (ibid). German and English intellectuals averred on the other hand that Northern Europeans were bearers of Protestantism and a work ethic that made them the natural leaders of the world. Historically this opposition was also played out between Latin American and North American intellectuals (ibid). In their nationalist scheme, political leaders on Curaçao translated these ideas to claim that the island’s ‘autochthons’ were bearers of a superior Latin Caribbean culture and the inhabitants of the Dutch Windward islands were part of a less refined English Caribbean.[x] This was one of the ways they sought to legitimize the fact that in the Dutch Antillean parliament, Curaçaolean parliamentary officials have the ultimate say with regards to the matters of the other Dutch Antillean islands.[xi]

In DJ Shadow’s opinion, the United States of America was made up of the similar presences as the Caribbean. For him the only differences were that of size and the fact that the US had surpassed Europe as far as political and economic might is concerned. This was according to him the main reason why many Europeans disliked and ridiculed these North Americans.

Europe build America, so basically America is the baby brother of Europe. Yet they clash because baby brother don’t want to listen to big brother and want to take over. But I ain’t in that with them Boo (instead of Bro for brother, SXMers say Boo). I love New York and they treat me nice over there. And when they come here most of them does behave well proper. Yes is Babylon capital (the US) and yes Bush is a war man, but you got give Jack his Jacket.

As with the West Indies, however, the US also remained a victim of nationalism camouflaged in multicultural rhetorics of belonging. As is the case elsewhere, here too one found politicians seeking to delude the ordinary folk.

They too living the scenario of their politricksians. Clinton was bad too but Bush is a dirty motherfucker.

While living and studying in Miami and New York DJ Shadow lived in a country where ‘race’ combined with ethnicity seeped through all areas of life. The first time he was pulled over by a police officer and thoroughly searched, he knew it was because of the color of his skin and his accent. One of the cops who pulled him over was dark skinned showing, according to him, how many black and white Americans had ‘the racial thing in them‘.

While ideas of ‘race’ combined with ethnicity are not exclusive to the US it was there that DJ Shadow became fully aware of their impact in structuring and legitimating power relations. This is an argument that has been put forward by several African-Americanists (West 1998, Higginbottam 1996).[xii] In Western Europe he came face to face with the continent he identified as having bred this evil.

DJ Shadow’s European Experiences

In 1993, DJ Shadow traveled to Europe, one of the places that played a major role in the Americas. He stayed there for 6 years, residing in Amsterdam, Berlin, London, and Madrid. What made the most impact on DJ Shadow was the bureaucratic efficiency in these Western European countries. He chided the government officials on SXM for their inefficiency and explicit clientelistic attitude.

I live in Holland, I realize that if SXM would run the way Holland is run, everything would be on the straight and narrow. But here [SXM] they take so much different corners and forget the main road, so they end up on a side street and can’t get back out.

Nonetheless, while he admired Western European societies for there bureaucratic efficiency, he criticized them for not using their power to right the historical and contemporary wrongs they caused. He claimed that while these countries are well off, they do not do enough to alleviate the disparate conditions faced by most in the Global South. For him this state of affairs was also internally visible in the racism that immigrants hailing from the Global South face. Many Western Europeans still wished to consider persons that were ‘taxonomically identified’ as being ‘non-European’ as intruders that have stormed their shores without any historical precedent. There too the Shadow averred one found a hierarchical if not exclusionary politics of belonging.

You see it there every day the way they stigmatize Morrocans, Turks, Surinamers, Africans, basically the Third World massive. They want to forget that they went to those countries first and loot them. They want to forget that they went to Africa and took people from anywhere they could get them. They sold them. Families that were together were scattered. They needed big strong bucks to do the work that they needed to do. They who started this thing. Now they want to forget. When they see these people in Europe and see the poverty in the world, they should know it is not only about them.

What DJ Shadow was articulating was that ‘the involuntary association’, as Wilson Harris termed it, between lighter skinned Westerners and the darker skinned peoples of the Global South, during the colonial era was constitutive of what both of them became.

‘In the selection of a thread upon which to string likenesses that are consolidated into the status of a privileged ruling family, clearly cultures reject others who remain nevertheless the hidden unacknowledged kith and kin, let us say, of the chosen ones. The rejection constitutes both a chasm or a divide in humanity and a context of involuntary association between the chosen ones and the outcast ones. The relationship is involuntary in that, though, on the one hand, it is plain and obvious, privileged status within that relationship endorses by degrees, on the other hand, a callous upon humanity. And that callous becomes so apparently normal that a blindness develops, a blindness that negates relationship between the privileged caste and the outcast’ (Harris 1998: 28)

The discrimination inflicted upon immigrants from the Global South was for DJ Shadow an indication that this historical entanglement was not being properly acknowledged. He used the horrors of slavery as a trope to bring home the point that colonialism entailed the dehumanization of ‘Third World peoples’ in general, and persons of African descent in particular, and that this needed to be acknowledged as a crime against humanity, a wound that should also bother lighter skinned Europeans although their ancestors did not undergo this humiliation. Europe’s wealth is partly based upon the blood, sweat, and tears, of the many faceless and nameless colonized peoples who threaded the proverbial winepress. Europe was born out of these heinous crimes.[xiii]

DJ Shadow felt that the Othering of non-Western immigrants in racial and ethnic terms was also at play in the manner in which many ‘autocthonous’ Dutch treated their Dutch West Indian counterparts. While Dutch West Indians are legally speaking equal to those in the Netherlands many ‘autochthons’ still consider them foreigners. He felt that if the Dutch Kingdom was to function effectively and justly the same standards, politics of belonging, should apply in all Dutch territories. The parliament in The Hague should act on behalf of its citizens in the West Indies when the politicians failed to do their jobs correctly. While he was also critical of the French, he felt at least the citizens of these overseas territories enjoyed the same social benefits as those in Paris.

The French have the racial thing too, but when you go any French island, drive around on the French side and, you can see that they helping out, that they keeping things crisp. On the French side the politricksians can thief but they still have to be fair cause them boys in France watching them and will intervene if they have too. On the French side they have to thief and rule the same way they does thief and rule in France: never too openly so they don’t get catch. But the Dutch does sit down and don’t put all their effort into regulating the problems that they have here. I don’t think they put effort into making sure that the SXM government is just and that they do the just and right thing. They just let them do what they want and when they realize things getting out of hand then they clamp down on them. Regulate it before they fuck up. That is what irritates me about the Dutch.

For DJ Shadow talk about neo-colonialism by elected officials on SXM was just a disguise of the fact that they too had embraced the tenets of nationalism. The metropolitan Dutch were seen as belonging to a different nation than themselves.

The Dutch should not worry when they hear we ‘politricksians’ say SXM should be left alone, that they have rights as a nation. No, that would give them more leeway to fuck up the country even more. All of we are Dutch. The Dutch Antillean is Dutch. So if they aren’t doing it right somebody has to show them, whether they call it neo-colonialism, colonialism or whatever. If they ain’t doing it right Holland should step in.

The Shadow’s Option

To me there was a paradox in DJ Shadow’s last comments on Dutch SXMers being Dutch. Wasn’t this rejecting nationalism at the front door and welcoming it through the back? He noted my concerns, but smilingly admitted that the confusion in my mind was because I was not being ‘real’, meaning realistic. I was not being an anti-national pragmatist. For all his critique of France and the Netherlands, he felt that under the present global conditions SXM should never dream of severing its constitutional ties with these Western European countries. And he saw more political autonomy as the beginning of that process

Once you start that thing about autonomy, there is no way back. The only the way is forward, independence. And I don’t want to go there. I like it here. This is just fine with me.

He then reiterated his fundamental dislike of nationalism and he claimed that more political autonomy followed inevitably by constitutionally breaking with France and the Netherlands did not entail leaving nationalism behind.

Like I tell you already that nation business is just tribalism. I following Jah and not the scenarios of ‘the politricksians’. I and I for unity, seen. When them politricksians say SXM must rule itself, and people believe them, then they falling into the same trap of the nation business. That there is a dead end.

According to DJ Shadow the trap of ‘the nation business’, nationalist projects, was dangerous. Those that had embarked on projects of more political autonomy and eventually political independence had not done well. In fact he argued it had worsened the life changes of the poor in these countries. In his explanation he did not allude to the trade embargoes and unequal trade relations between the US and Western Europe and independent Caribbean countries such as Jamaica, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic. He was explaining how it is in those countries and not the external reasons that led to this.

Personally I have seen what has happened to independent countries. I don’t want my child growing up in it even though my family ain.t hand to mouth [are not poor]. It is a matter of the principle cause live is a funny thing. Today you up tomorrow you down, you overs? In the Dominican Republic I saw factories among factories and there is no middle class. There is just rich and poor. And the poor is constantly living off of credit. The poor have to go and credit a food, some rice, corn, sugar, and salt. That’s poverty, that’s some hard ass living. I drive some places on the island where as far as your eyes can see is zinc roof alone, no tile floor, outhouse [bath room in the yard]. You understand that is poverty. And this is an independent island with all these resources, and nobody want to touch them. Take Jamaica, this country produces everything: clothes, shoes, aluminum, but nobody want to touch them. They have no value internationally speaking, their money ain’t worth shit. Why would you want to do that to your people? You see where I coming from.

Many SXMers I spoke to expressed similar views. They too felt that embarking upon the road of nationalism, in the form of more political autonomy from France and the Netherlands was unwise. Especially the working class newcomers furnished me with example after example about the abject poverty that they faced living in independent countries. Others told me about being victimized partially because they belonged to the internal enemies of the nation.

DJ Shadow was now on a roll, philosophizing with conviction, and all I had to do was sit down and listen. He continued that even if SXMers influenced by fringe politicians wanted to take the risk of more political autonomy and eventually full political independence their island had its size against it.

This island is 37 square miles. The Dutch side is the smaller part: 17 square miles. Let’s say the Dutch side wants to go independent. Out of that 17 square miles there is a pond. Let’s say about 5 square miles out of that 17 is taken up by water. Your down to 12 square miles of land. How are you going to go independent with just 12 square miles of land? Where are you going? You can’t travel to the French side as you feel anymore. I don’t see the logic in it. To me it is ludicrous, it is ridiculous, it is foolish. If they ever think about something like that, if SXM go independent, I leaving. For real, it don’t make sense staying, I don’t see how you going to survive.

DJ Shadow then touched upon SXM’s precarious dependence on tourism. He said that this was a public secret, as was the fact that the reason why most SXMers were residing on the island was due to the money tie system. They would, therefore, not think twice of leaving if they got wind that fringe ‘politricksians’ had convinced the parliament in France and the Netherlands to grant the island more political autonomy or full independence.[xiv] He admitted that he, too, would leave without hesitation.

What do we have tourism, nah man. I don’t believe in that, because there is nothing generating but tourism. After 911 SXM feel it cause Americans didn’t want to take the plane no more. The next thing you know you get another lunatic like Bin Laden say he going to sink a cruise ship this time, he don’t want any planes no more. Where you think they coming? Cruise ships stop float, they ain’t coming here no more, so what we going to eat. What we going survive on? That is our only means of survival. We don’t have any factories. That is why I telling you I leaving if any politricksian even think about doing something like that. But not me alone, I telling you almost everybody going to leave. We SXMers, all of us, ‘local’ and newcomer alike, have a nationalism for the good times, we don’t believe on staying on a sinking ship, we all know that deep down it is all about the money tie system. Even though we love this country, even though I love this country, it is my home and I don’t want to leave it, but I will if I have to. First and foremost I have to take care of myself and my family.

DJ Shadow then argued that under the present constitution there were concrete benefits in being part of France and the Netherlands. It meant an ability to travel the world unperturbed by immigration officers and to settle in greener pastures when and if SXM’s tourist economy declined. Under the present conditions he did not feel as though he was living under an oppressive French and Dutch regime.

Things good right now so I don’t see why we should change it. You know the saying you must never bite the hand that feeds you. Well that is what I am about. Curse the hand, yes. Tell it when it fuck up, it fuck up. Tell it when it being unfair. But don’t bite it. This is not a colonial thing or a slavery thing like in Kunta Kente days. Them days long gone. This is one country run by two entities but living on the Dutch side I can drive to the French side all day everyday without a problem. Nobody can’t tell me nothing. And if the gendarmerie tell me I can’t go over there something is wrong. Something got to be seriously wrong, because there is no border, no checkpoint. Ask a French man [French SXMer] and he’ll tell you he love that French passport. I telling you I don’t believe in giving up my Dutch passport, my right to be a European citizen. If SXM go independent you are no longer a European citizen, you’re a SXMer. I need to travel B. Ask anybody and they’ll tell you they love that European passport cause when things go bad they can leave and go somewhere else to feed their children.

Was it all a question of being against the delusion of national belonging, but making the best of present condition and thus accepting being part of France and the Netherlands? Yes. DJ Shadow had a solution to nationalism though, which was his version of the unity of Man. If each and every person recognized their divinity within, their Rastafari individuality, nationalism would be overcome. Nevertheless he believed that nationalism and the issue of belonging it induced would be replaced with other exclusive categorizations through which men and women would once again be lured to discriminate each other.

Fi real Star. The solution is simple if every man see himself truly. See that he have a Devil and the God inside a lot of this tribal business would done. All Man have to see that. They have to be overs that. Then Babylon going fall down. But it ain’t going to be over then. Life is struggle and that is a never-ending story. Mystically it is a continuing struggle between good and evil, between God and the Devil inside of us. You got the Devil over here and his troops and God over there with his. Like I say it’s a never-ending story so something else will come up.

I understood him immediately, for as an anthropologist I knew that the track record of humanity since we emerged 100.000 years ago has been bad one. In the name of Reason, Race, and Religion we have inflicted innumerable pains upon each other. My hope resides in the fact that many are beginning to glimpse that all societies and ecological systems are interrelated. What we are still lacking, however, is the global acceptance and a pragmatic ethics attuned to this condition of worldness, to use Glissant’s term.

…this earthly totality that has now come to pass suffers from a radical absence, the absence of our consent. Even while we of the human community experience this condition, we remain viscerally attached to the origins of the histories of our particular communities, our cultures, peoples, or nations. And surely we are right to maintain these attachments, since no one lives suspended in the air, and since we must give voice to our own place. But I also must put this place of mine in relation to all the places of the world. Worldness is exactly what we all have in common today: the dimension I find myself inhabiting and the relation we may lose ourselves in. The wretched other side of worldness is what is called globalization or the global market: reduction to the bare basics, the rush to the bottom, standardization, the imposition of multinational corporations with their ethos of bestial (or all too human) profit, circles whose circumference is everywhere and whose center is nowhere. What I would like to tell you is that we cannot really see, understand, or contest the ravages of globalization in us and around us unless we activate the leaven of our worldness. (Glissant 2002: 287-288)

I wanted DJ Shadow to continue philosophizing, and maybe I would have been able to distill if he thought our acceptance of our worldness, our global interrelation, would still the divinity and the demonical we supposedly carry within us, but he had enough. He was tired and would just like to relax and not think or rap about politics and things of that nature. I understood and bode him farewell. Coming out of the studio and waving down a bus to take me home I thought, if there was a mystical battle raging in each and everyone one us, maybe SXMers like DJ Shadow were wise to play it safe. Be ideologically against embarking on the road of nationalism, assert the recognition of Rastafari individuality on the island, but remain a pragmatist, safely in the bosom of France and the Netherlands were the winds of Capitalism were relatively speaking rather mild. Worldness was a condition most of us still had to accept. It is still in the making.

As I reflect back on that meeting I realize that DJ Shadow was the ultimate politician – someone who is able to entice others to follow his or her vision for the political future of SXM society – and deep down inside he probably knew it. No politician I had met on the island, those with and without political backing, was as skilful as he was in addressing people from all walks of life.

He was also a well-spoken organic intellectual that had produced a universal category that went beyond national affiliation. His philosophy of Rastafari individuality was a radical democratic move that deconstructed the myth of the autonomous individual. In the end, all great thinkers remind us that life unfolds on two realms: history and destiny. We make history, and in doing so our sense of self, but we do so under conditions that are part of a multitude of human and non-human interactions. The community that nurtures us exists because it interacts and reacts to other communities and the environment. It is not bounded; like the selves it produces, it is itself a product of relations (c.f. Glissant 2000).

Those who recognize this know that one day our current organization of the world in nation-states will wither away. They are anti-national pragmatists that have accepted our condition of worldness.

NOTES

i. To inhabit the space of an anti-national pragmatist is to be ideologically against nationalism. This entails that in one’s praxis one constantly seeks to open up nationstates to the Other, in the hope that one day the logic of the nation will be superceded.

ii. Radio is the most influential local media on the island. The viewing and reading practices of most SXMers are geared to American cable TV and regional newspapers. This makes the influence of radio disc jockeys even more pronounced.

iii. In 2002 I spent a year on SXM conducting fieldwork among popular radio disc jockeys.

iv. One has to make a distinction between state formation and the imagined community of nation-states in which we have divided the world today. The former is as old as the first human settlements at rivers such as the Tigris, Nile, and the Ganges (approximately 10.000 years ago). The peoples living in the kingdoms that developed out of these settlements did not see themselves as part of a single nation. They were distinct peoples and kinship groups ruled through the mediation of vassals and feudal lords. They did not see themselves as sons of the soil, equals, across ethnic boundaries. Nation-states are new inventions. The USA was the first nation-state founded in 1776 followed by Haiti in 1804. By the end of the 1820s most Latin American countries were independent nation-states. On the other hand nation-states that present themselves as having existed since time immemorial such as Germany and Italy were only founded in respectively 1870 and 1871. A little acknowledged fact is thus that during the Berlin conference of 1884-1885–which led to the formal division of Africa and Asia among the European powers–there were already post colonies in the Americas.

v. I am quite aware that the nation-state is also gendered, but such a discussion does not tie into the points made by DJ Shadow. It is an important omission but one that if elaborated on would exceed the scope of this chapter.

vi. The bad track records of nationalism have led some to argue that this social construct has to be transcended. This what Derrida has to say on the matter: ‘like those of blood, nationalism of the native soil not only sow hatred, not only commit crimes, they have no future, they promise nothing even if, like stupidity or the unconscious, they hold fast to life’. (Derrida 1994: 169) See also Glissant (2002, 2000), who espouses similar views. Others have argued that in a world where a further expansion of global capitalism in the guise of WTO recommendations, which advocates that all tariffs of trade should be lifted, it is unwise to promote a wholesale deconstruction of nationalism and nation-states. Doing this would exacerbate the poverty of millions already adversely affected by capitalism. One has to change the global configuration before disbanding nationalism. For an ethnographic study that forwards this point see Glick Schiller, N. & Fouron, G. Georges woke up laughing: long distance nationalism & the search for home. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001.

vii. These are the Shadow’s views. It is congruent with the views of many SXMers. Academically speaking, however, one cannot easily compare the colonization and decolonization process of Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Perhaps we need to rethink the adequacy of capturing the realities these countries in concepts such as colonialism and post-colonialism. In doing so we might come to the conclusion that we need new concepts and classificatory schemes. This may unfreeze the manner in which ‘the West’ and ‘non-West’ are framed as immutable and internally consistent positions. These questions escape the scope of this essay.

viii. Bob Marley even sang at the independence celebration of Zimbabwe.

ix. See also Gilroy (2000, 1992), Glissant (1999), Price (1998), Mintz & Price (1976). These authors have averred that to research Caribbean racism without taking the foundational role in plays in Western polities into account is a grave mistake. The position of blacks in these societies directly inflects on how Caribbean societies deal with this matter.

x. Curaçao like Cuba, Puerto Rico, Aruba, and Venezuela see themselves as part of Latin Caribbean culture.

xi. The Dutch Kingdom consists of three parliaments: the Netherlands, the Dutch Antilles, and Aruba. Dutch SXM is part of the Dutch Antillean polity, which consists of five islands. In this political constellation which regulates the internal affairs, Curaçao, as the largest island, with numerically the most inhabitants, has a virtual monopoly in parliament. 14 of the 22 seats are occupied by Curaçaolean politicians. Due to the coming of age of Dutch SXM as an economic power rivaling Curaçao, the protests of the other smaller islands, and the further integration of the Dutch Kingdom within the EU, there are plans to change the political constitution. How this will be arranged is still under discussion. What is sure is that neither Dutch SXM nor the other islands will become independent in the nearby future.

xii. See also West (1994), Frankenberg (1993), Rose et al. (1995), The Black Public Sphere Collective (1995).

xiii. For interesting studies that shows how the idea of Europe as a distinct continent came into being based upon the colonization of America and thereafter the rest of the world see Trouillot (1995), Hulme & Jordanova (1990).

xiv. This is of course a hypothetical situation, since both France and the Netherlands are committed to stay on SXM.

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict, Imagined Communities. Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. London: Verso, 1991.

Baumann, Ger, The Multicultural Riddle: rethinking national, ethnic, and religious identities. London: Routledge, 1999.

Besson, Jean, Martha Brae’s Two Histories: European expansion and Caribbean culturebuilding in Jamaica. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Black Public Sphere Collective, The, The Black Public Sphere: a public sphere book. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955.

Brown, David, Contemporary Nationalism: civic, ethnocultural & multicultural politics. London: Routledge, 2000.

Derrida, Jacques, On Cosmopolitanism and Forgiveness. London: Routledge, 2001.

Derrida, Jacques, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Frankenberg, Ruth, White Women, Race Matters: the social construction of whiteness. London: Routledge, 1993.

Gilroy, Paul, Between Camps: nations, cultures, and the allure of race. London: The Penguin Press, 2000.

Gilroy, Paul, The Black Atlantic: modernity and double consciousness. London: Verso, 1992.

Glick, Nina, Schiller & Georges Fouron , Georges woke up laughing: long distance nationalism & the search for home. Durham: Duke University Press, 2001.

Glissant, Éduoard, The Poetics of Relation. translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000.

Glissant, Édouard, Caribbean Discourse: selected essays. Trans. Micheal J. Dash. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1999.

Hall, Stuart, Cultural Identity and Cinematic representation. In: Mbye. B. Cham (Ed), Ex-iles: essays on Caribbean cinema. New Jersey: Africa World Press, 1992: pp. 220-236.

Hallward, Peter, Hiatian Inspiration: on the bicenentary of Haiti.s independence. In: Radical Philosophy, Issue 123. 2004: pp. 2-7.

Harris, Wilson, Creoleness: the crossroads of a civilization. In: Balutansky, K.M. & Sourieau, M. Caribbean Creolization: reflections on the cultural dynamics of language, literature, and identity. Tallahassee: University Press of Florida, 1998: p. 23-35.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply