Extended Statehood In The Caribbean ~ The French Départements D’Outre Mer. Guadeloupe And Martinique

No comments yet Introduction

Introduction

In 1946, the French Antilles inaugurated a heterodox process of ‘decolonization through institutional assimilation’. A long historical movement, initiated during the early periods of colonization, made of rupture and discontinuities but sustained by a universalist ambition, found its ultimate consecration in the so-called law of assimilation of 19 March 1946. A new expression – Overseas Department (Département d’outre mer, or DOM) – enriched the juridical-political vocabulary, pointing out both the geographical and historical difference as well as the similarity of political and administrative structures with the Départements of the Metropole. Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Réunion located in the Indian Ocean, and French Guiana situated between Surinam and Brazil in northern South America, became part of the ‘Four Oldest Colonies’. They were integrated within metropolitan France and have been regarded as European territories since 1957.

Départementalisation is another term used to refer to institutional assimilation, while highlighting the unfinished character of the assimilation process. That notion applies not only to institutions, but also to people, from a juridical and a cultural point of view.[i] From a historical perspective, the 1946 départementalisation thus achieves the synthesis contemplated by the reporter of the Constitution of the year III (1795), Boissy d’Anglas,[ii] stemming from a dual question: is it necessary to implant in the ‘Oldest Colonies’, independently from the locally expressed will, an administrative system identical to the current one of the mainland (assimilation of institutions)? Is it necessary to extend to the whole population of these colonies an identical system of values and juridical norms as of the mainland, thereby enlarging the circle of members of the ‘motherland’ (assimilation of people)? Such a colonial doctrine, which originated from the concept of a unified French State, had the tendency to deny all public expression of identity other than its own, and to marginalise all the others for the benefit of citizen allegiance.

Nevertheless, such a claim that so closely associates legal assimilation and cultural assimilation, is a source of many paradoxes that anthropologists have researched for a long time. Supported by an assimilationist ideal in which deep traces of the Ancient Regime are still perceptible, and fed on a universalist claim that the revolutionary heritage continuously reinforced, the colonial project that ensued was no less than a ‘tremendous difference-producing machine’.[iii] The bringing together of peoples from extremely diverse backgrounds to form societies – according to a historical trajectory of a most remarkable nature – was a strong factor in the creation of cultural and social spaces which kept the assimilationist dynamic at bay. It is then indisputable that the French colonial device and the French State had long been resistant to any form of cultural and political autonomy. Nonetheless, these forces emerged and did so without strict alignment to metropolitan norms.

Upon closer examination, the processes of the confinement and marginalisation of dominated groups in deliberately unequal frameworks contributed to the emergence of the true identities of these groups; groups for which social equality, inherent to citizenship, could only be achieved through the claim of cultural specificities such as displayed by the negritude of Aimee Cesar.[iv] Because of the lack of respect for cultural idiosyncrasies, Aimé Césaire’s project tried to reconcile the equality claim with the claims of specificity. Historically, juridical assimilation was far from being a univocal process: the evocative power of this term, whether denouncing its illusive or hoaxing character, or viewed as some sort of logical result, true to the revolutionary ideal, only reflected the extreme complexity of the situation that it claims to designate. That process did not result exclusively from the pressures exerted by the colonial power in the name of the republican myth of emancipation; to a large extent, it benefited from the support of certain social and local categories, and sometimes corresponded to dynamics and demands emanating from the Antillean societies themselves. Today, this results in a ‘total system’, as Marcel Mauss[v] conceived this notion, which clearly interferes in all dimensions – political, economic, social and cultural – of the insular societies. From this point of view, this chapter deals with the following issues:

1) political status, central control and local autonomy;

2) citizenship, identity, culture and migration;

3) economics, employment and welfare;

4) education;

5) rule of law and democracy;

6) crime, international security and diplomacy.

Political Status, Central Control and Local Autonomy

As of 1946, Martinique and Guadeloupe were granted the administrative status of Département. All territorial institutions, whether Municipalité, Département, or Région, operate like their metropolitan equivalents. However, the identical nature of political and administrative structures between the overseas Départements and their metropolitan counterparts has resulted in creating a mono-départemental region[vi]: a super-positioning of the two administrative constituencies of the Département and the Région. The overseas Départements are subject to the same rules as their counterparts in mainland France. Nevertheless, in Martinique and Guadeloupe, the Council (of official representatives) of the Département maintains specific tax allotments as well as proposal and advisory powers ‘adapting legislative and regulatory texts’ (the 26 April, 1960 Decrees).[vii] By and large, the Département is an administrative management unit; its main area of competency lies in rural infrastructure, economic and social endeavors, harbors, middle schools, school transportation and social aid.

The Région has power to promote economic, social, cultural and scientific development, and to negotiate a six-year economic scheme (‘contrat de plan‘). It also has powers in matters of vocational training and apprenticeship as well as domestic transportation. Finally, it manages the secondary school system. The Région’s major areas of action are in agriculture and rural infrastructure, transportation and communication, tourism, economic undertakings, education, and culture.

The political-administrative system is marked by complexity, due to many different levels of administration. This problem is far from been totally solved, despite the premise of ‘blocs of competency’ as decided by French legislators: each collective body – Municipalité, Département, Région – is assigned a certain number of areas of competency in which none of the other institutions may, in theory, interfere. In practice, however, the

overlapping of competencies is reinforced by the coexistence of two locally elected assemblies, the Regional Council[viii] and the General Council for one single territory, which makes for a conflicting situation and incites the territorial institutions, to compete among each other. Moreover, the social-cultural environment in Martinique induces institutions to confer upon themselves fields of competency, which they consider exclusively theirs.

Hence, not only are there heavy social demands for public intervention but also the small size of the territory puts these institutions at the centre of all debates and propels them to become involved in areas where they do not have recognized competence. Finally, legislative texts have not been able to eliminate situations of competing involvement. For example, the Région is an active participant in environment policies and in safeguarding

heritage, while at the same time, the Municipalité and the Département have been assigned to enhance and safeguard heritage. The policy of housing is also shared between the Région, in charge of defining priorities concerning housing which may compete for State aid, and the Département and the Municipalité which also define their priorities in the area of housing and which have the power to set up local housing programs.

However, the law has instituted the principle of a total absence of horizontal. supervision; that is to say, no institution may claim to exercise any hierarchical power over the other. But once again, this principle is watered down due to the role of the Région and the Département in the allocation of subsidies, which confers substantial powers upon the presidents of the regional and departmental councils. They are empowered to negotiate with the mayors whose capabilities depend on those subsidies.

The means of financing local institutions in Martinique and Guadeloupe (and the overseas Départements in general) differs from what prevails in mainland France. Without going into complex detail, the municipality budgets are for most part obtained by financial disbursements from the French State. Local institutions benefit from a specific system of substantial indirect taxation, the so called octroi de mer, which is a duty collected on imports and consumer goods, and a fuel tax. Nonetheless the finances of local institutions are fragile. The slower development pace in comparison with mainland France (which under all circumstances still remains the standard) encourages escalating expenditure. The DOM face a considerable lack of infrastructure such as roads, low-cost housing, schools, and cultural centers. Moreover, the rather weak economy and the high rate of unemployment put weighty claims on local finances.

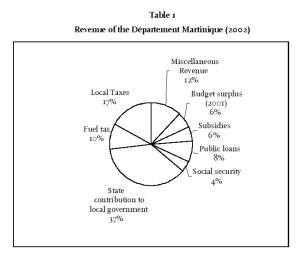

A review of municipal, departmental and regional finances reveals a double dependency on the State, firstly because of the weak financial autonomy of the Collectivités territoriales, and secondly because of the weight of indirect taxes based on consumption in the Départements d’outre-mer. The main source of revenue of the municipalities consists of the octroi de mer (customs duties), of which Euro 122.2 million, i.e. 22% of the total revenue, was collected in Guadeloupe in 2001. The local taxes reached Euro 111.3 million, i.e. Euro 216 per inhabitant as compared to Euro 381 in Metropolitan France. For both islands non-fiscal revenue plays an important compensating role and constitutes a great part of the financial resources of the departmental institutions; it amounted to 57% of the operating budget of the Départment of Martinique in 2002. This revenue originates for the most part from contributions of the French State, as shown in the pie chart here below, representing the revenue of the Départment of Martinique (IEDOM, 2004):

– State contribution to local government (37%)

– Local Tax (17%)

– Miscellaneous revenue (12%)

– Fuel tax (10%)

– Public loans (8%)

– Subsidies (6%)

– Budget surplus (6%)

– Social security (4%)

The State completes this administrative architecture. The French Antilles come directly under all the technical ministries in Paris, as do the other Départements or Régions in mainland France. But there is also a ministry – the Overseas Ministry – specifically in charge of the overseas Territories and Départements. As the offspring of the former Ministry of the Colonies, its role is to work with the other technical ministries in order to foster the specific interests of the overseas regions. Its budget is relatively small when compared to that of other ministries. Locally, the State is represented by the Prefect and by administrative agencies, which serve as an extension of the Parisian ministries. It should be noted that the Prefect, in addition to his functions of Prefect of the Département and of the Région, exercises competencies conferred upon the government in matters of domestic and external security. The French government appoints him and he exercises jurisdiction under the exclusive authority of the government.[ix] Despite growing local autonomy, a result of the decentralization program of 1982[x], the Prefect holds considerable prestige, especially through his significant role in mediating labor conflicts.

Historically, the French State has somehow modeled the insular societies and still has a substantial impact due to considerable public transfers. In 2002, these public transfers, including social transfers, reached Euro 1.3 billion for Martinique, and Euro 1.8 billion for Guadeloupe, which represents 3,347 Euro per inhabitant in the first case and 4,055 Euro per inhabitant for the second.[xi] The prefectorial institution reflects the weight exercised by the State. Altogether the State penetrates deeply the collective consciousness and through its presence continues to influence the Antillean imagination.

To complete this picture, the role played by European institutions must be included. Due to their status as DOM, Martinique and Guadeloupe are considered European territories, and as such, benefit generously from regional policies funded by European financial structures. However, this substantial European presence is offset by a low level of Antillean involvement in the operations of EU political institutions. The ‘democratic deficit’, so often mentioned by member states, expresses itself in the French Antilles with great indifference at the political level. For example, there was less than 20% participation in the 1994 European Parliamentary elections in Martinique; in 1999, the rate of participation plunged to the historically low level of 12%, before climbing again to 18% in 2004. This compares rather poorly with the lowest participation rate in continental France, which was 43% in 2004. The electoral indifference with regards to the EU, despite Europe’s active involvement in the operation of the islands’ economies, can be explained by two factors. On the one hand, European citizenship remains abstract to Antilleans and is not able to supplant their allegiance to the French State. In other words, there is a very weak identification with the European environment, in particular from a cultural point of view. Hence the creation of the common market in the 1980s was met with distrust as in some circles Europe was considered to be a danger to Antillean interests. On the other hand, the process of economic and political integration into the EU has been coupled in recent years with a consolidation of ties within the Caribbean region. Thus the French West Indians seem to have multiple allegiances and attempt to proclaim themselves as being an integral part of the Caribbean area while at the same time their economic and political ties with the EU are in the process of being strengthened.

One of the main features of local government in Martinique and Guadeloupe resides in an increase in the levels of administration and local and central intervention. This has resulted in unstable collaboration, rivalry and conflict in implementing local policies, as well as a struggle for local leadership, which can be quite fierce at times. The French government recognized this competence problem and in the early 1980s attempts were made to implement a decentralization plan. Decentralization was not intended as a specific solution to the problems of the French West Indies or the overseas Départements in general. But given the persistence of autonomism and the notion of independence since the 1950s, the socialist government in France and its local allies, notably Aimé Césaire’s Parti Progressiste Martiniquais (PPM), considered decentralization an answer to the appeal for change. Therefore the measures taken in metropolitan France were adapted to the exigencies of the overseas context to reinforce local government rule.

The consequences of this development were surprising. The accession to power of a socialist government in France combined with the success of autonomous/left-wing forces in Martinique and Guadeloupe altered the political landscape. The question of status, which was at the heart of the political debate since the 1950s, became secondary. The left-wing forces ceased to contest the juridical aspect of départementalisation. Rather, during the first half of the 1980s they became increasingly concerned with combating underdevelopment within the framework established by the decentralization reforms.

This stage in the development of political life in Martinique and Guadeloupe can be qualified as a depolarization effort and signified a tendency to decrease tension between the centre and the periphery. Local forces that had in the past contested the role of the French State were obliged to ask for its help in implementing development policies. For example, the PPM that since 1958 had been the most vocal opponent of the status quo (even if it had accepted the logic of economic dependency) became the principal guarantor and supporter of decentralization. In fact, Aimé Césaire’s party became the leading beneficiary of the very status quo it had fought in the past.

Thus the situation had changed considerably. Before, political life was organised around the divisions between right-wing parties, which favoured the process of départementalisation, and left-wing parties, which preferred political autonomy and independence movements. These divisions have certainly not disappeared. But the

French West Indies have witnessed the progressive ‘territorialisation’ of all the parties, including the right-wing in an attempt to keep their distance from mainland French political parties such as the UDF (Union pour la Démocratie Française) and the RPR (Rassemblement pour la République), and now the newly created UMP (Union pour un Mouvement Populaire) by asserting their local bases. With respect to the left-wing parties, whether it was the PPM or the Martinique Communist Party (PCM) or the Guadeloupe Communist Party (PCG), have since the 1950s claimed, if not independence, then at least autonomy from their mainland counterparts. In other words, the local political systems do possess their own internal dynamics; they are far from being simply a carbon copy of the mainland France models. Indeed, one of the main characteristics is excessive fragmentation due to the great numbers of political movements, some of which develop through fissiparous behavior. The political system is definitely witnessing a crisis in terms of representative democracy. Traditional political parties no longer seem able to respond satisfactorily to emerging aspirations, whereas other movements – literary, political or cultural – which are flourishing within ‘civil society’ don’t seem to be able to take over, even if they seek to mobilize the population around issues that are currently en vogue such as environmental protection and preservation of cultural traditions. Decentralization enabled creative potential to be unleashed and revealed the capacity of local leaders to implement local policies. However, it reinforced dependency since it never questioned the old egalitarian claim while local institutions had to face up to an increase in financial demands. The earlier depolarization efforts were followed at the end of the 1980s by a revival of status claims, and by tensions between the State and the heads of the départemental and régional executives. Negotiations concerning institutional changes followed. These negotiations led in December 2003 to the organization of a plebiscite on the creation in Guadeloupe and Martinique of a new local entity that would replace the départements and the régions.

The proposition to create a new collectivité territoriale was meant to simplify the institutional landscape by reducing the number of structures so as to redefine the State’s role and to strengthen local powers. It met the zealous requests that have for years been addressed to the French Government and was backed by a strong majority of local representatives. The new collectivité would exert not only the competences devolved to the département and the région, but also competences transferred by the State, particularly in the fields of territorial development, urbanism, environment, land and sea transport, culture and regional cooperation. This reform would essentially have answered the local representatives. aims to employ wider responsibilities and so have better control over the institutional mechanisms of economic, social and cultural development. At the same time this reform was meant to respect the attachment of Martinicans and Guadeloupeans to social rights and their links to Europe.

The results of this election are interesting as they reveal the ambivalence of both the political elites and the citizenry. The massive victory of the ‘no’ option in Guadeloupe (72.9%) was a bitter failure for the President of the Région, Lucette Michaux-Chevry, a charismatic leader who was in favor of reform.[xii] It also expresses the will to preserve acquired rights. Though narrower in Martinique, the victory of the no option (50.4%) reveals an instinctive mistrust with regard to any change that may call into question the real or perceived advantages related to the départementalisation. The outcome of the plebiscite was a rejection of any institutional change that supposedly could have paved the way for more autonomy or even independence. Interestingly, three months after the plebiscite, the citizens of Martinique re-elected Alfred Marie-Jeanne, a supporter of independence and president of the Mouvement Indépendantiste Martiniquais (MIM), as head of the regional executive. Such contrasting results show the ambivalence embedded in the behavior of the citizens of Martinique who attempt to reconcile their identity assertion with an allegiance to the French realm.

All in all, the political status of the French West Indies is characterised by a strong financial dependency on the Metropole and increasingly also on the EU. Moreover, institutional pluralism is ubiquitous as a consequence of the multiplicity of the local and State actors participating in the management of insular affairs. The strong presence of the State through public and social transfers, considerably limits local representatives freedom of action despite the decentralisation reforms of the 1980s. Not only is the politico-institutional status persistently contested, but there is also an imbalanced development model, which shows strong structural unemployment (more than 25% of the active population), coupled with endemic under-employment. Nonetheless the response of the central power – sometimes backed by its local supporters – is invariably an elaboration and implementation of public and institutional policies that are based on the principles of Republican equality. Through measures of ‘positive discrimination’ (affirmative action), structural local handicaps such as the small size of the market or the weakness of the production mechanism are taken into consideration.

From the 1960 Loi de programme to the 2003 Loi de programme pour l’outre mer (LOPOM) through to the 1986 Loi de programme and the Loi d’orientation pour l’outre mer (LOOM) of 13 December, 2000, the same logic is at work: a package of economic and social measures is presented as an answer to the malaise and local claims for improvement. These measures usually consist of injecting public funds in the insular economy and in different kinds of backing such as social transfers, tax exemptions or a moratorium or reduction of social charges. These measures have created a problem of fine-tuning the public policies led by the State with those of the collectivités locales. More often than not, the collectivités locales are condemned to ‘socialize’ the consequences of measures of which they have no control, particularly in the field of economic policy. One cannot but admit that this system is based on a kind of ambiguous consensus that guarantees its continuation. Strengthening local autonomy, as demanded by the representatives, is not necessarily compatible with maintaining social and public transfers that have increased dependency on the State. Pierre Mesmer, former Ministre de l’ Outremer, compared autonomy at the beginning of the 1970s with a ‘divorce with alimony’ – thus illustrating that the State continues, under all circumstances, to retain a leading role in the running of local affairs.

Citizenship, Identity, Culture and Migration

The English sociologist Thomas Marshall[xiii] distinguished three stages and three forms in the fulfillment of modern citizenship: assertion of civil rights during the 18th century (phase of construction of the Liberal State); conquest of political rights during the 19th century (recognition of Universal Suffrage); and the organization of the social rights during the 20th century (development of the Welfare State). If these three constituents of citizenship are universal, Marshall’s chronology raises a problem when being applied to France, especially to its outermost territories[xiv].

The abolition of slavery in the French West Indies in 1848 signified indeed an acceleration of the historical process in which the three components of citizenship as highlighted by Marshall converged. Marshall’s three stages crystallized in one essential date, 1848, which brought about universal equality since freedom came with the plenitude of civil and political rights, and was logically followed by the fulfillment of social rights in 1946. Moreover, contrary to the vision of a linear and finalized evolution as suggested by Marshall’s theory, the experience of the French West Indies reveals that the authenticity of the citizen was from the beginning confronted with rival identifications which continue to this day to assert themselves.

At present, French citizens from Martinique and Guadeloupe benefit from all the rights inherent in French citizenship and from the inclusion of the two islands in the EU. The granting of civil and political rights since 1848 following the abolition of slavery thus enabled the newly liberated people, hitherto denied any political power, to participate in political activities. French West-Indians now take part in all local and national elections organised in France and each island sends six elected officials to the French Parliament (4 deputies and 2 senators). Regarding social rights, the situation proved to be more delicate. Social equality was gradually implemented from 1946 onwards and during this process contentious debates and social conflicts arose, which contradicted the idyllic vision of a harmonious development of citizenship and a progressive extension of its various – civil, political and social – dimensions.[xv]

Access to these rights did not go hand in hand with an alignment of cultural norms with the mainland. The process was complex for at least two reasons. Firstly, contacts between different cultures, including oppressive and unequal situations, do not automatically result in simply imitating or assimilating the traits of one group by another group and so modifying the behaviour of each.[xvi] Secondly, it seems that the construction of identity in Martinique and Guadeloupe was engineered by a superposition of subjective belongings. Without doubt, the assimilationist force of the State has been widely supported by its undeniable ability to tolerate an island space mediating a belonging in a broadened community through local attachments, which were being constantly

reconsidered.

This mediation operated within the framework of the political-administrative system of départementalisation. Representatives of the ‘island community’, accessing the State controlled resources in a urgent quest for equality, explicated the specifics that are compatible with integration within the French national orbit. In their everyday operations and relations with central government officers, they brought into play a certain autonomisation of the political island space.[xvii] Against the history of disappointment and disillusionment generated by the failure of départementalisation, this autonomisation favored a revival of native and cultural forms. Michel Giraud emphasizes that the social over-enhancing of ‘classic’ French culture, going hand-in-hand with a reduction of West Indian culture, was intrinsically linked to the credibility of the assimilative ideology of which départementalisation was the major product. Once this credibility was achieved through the contradictions and troubles of départementalisation, the West Indian cultural situation could not help but be affected.[xviii] This evolution resulted in a politicization of West Indian identities that took its first impulse from the conflicts created around the experience of départementalisation. For a long time, differences were crystallized in three approaches: supporters of political and cultural assimilation and, therefore of an identity re-shaped by the French State; the protagonists of cultural autonomy within the French orbit coupled with a respectful acknowledgement of differences; and finally the supporters of a radical otherness. The first attitude clearly articulated a strong electoral theme, the access to all rights and claims inherent in French citizenship and a valorization of French culture. The second tried to reconcile as a matter of principle a discourse based on themes of lesser electoral efficiency, like respect for cultural identity, the need to question the model of development and to reinforce the local powers on the one hand, and the logic of financial dependence on departmental institutions and the implementation of social programs, on the other. The third claimed independence. The weakening of the republican myth, associated with the rise of uncertainties linked to the construction of Europe, will most likely favor a redefinition of identity strategies.

Thus, the French West Indies exemplify to the extreme the classical tension between State universalism and local particularism or, if one prefers, between the search for an identity and the construction of a polity. In its process of imposing a unique allegiance, the French State relied on the republican myth, which was taken over by social groups, particularly the descendants of the slaves who form the majority of the population. The universalisation process that was engineered by the State nevertheless produced ambivalent results in so far as this process is accompanied by a reactivation of local culture and the development of local idiosyncrasies justifying specific claims.

The autonomist movement that asserted itself during the 1960s, even though its electoral basis remained limited, articulated claims of Martinique and Guadeloupe being separate national entities, of a political status based on local powers and financial and monetary autonomy, as well as respect for the dignity of the insular people. This development opened up potentially significant protest and facilitated also a multiplication of identity declarations through the 1970s in the cultural and political fields. Accelerated by the decentralization process of the 1980s, a true explosion of cultural activities and social expressions followed. Though the central powers had for a long time resisted every form of public expression of peripheral identity, from now on the existence of expressions of a different culture were acknowledged to such an extent that the French State financially participated in its development. Thanks to a loosening of tensions between central and insular powers, cultural initiatives and actions multiplied. However, the local assemblies acted often in an uncoordinated way and followed a process that emphasized collective teamwork rather than the development of clearly defined goals.[xix]

The new infatuation with the ‘cultural thing’ on the part of locally elected officials is full of ambiguities and paradoxes. These officials are more often than not permeated with a culture of automatic resistance to central power, but also quest for national (French) appraisal and national (French) gratefulness.[xx] At the same time, the elected members of the local assemblies try to outdo the State by deliberately distancing themselves from mainland France. In their relations with metropolitan and European centers, these local political leaders conduct a permanent presentation of ‘specificities’ as real symbols of their identity. They use ‘specificity’ erratically in negotiations with central and/or European authorities. In other words, local communities increasingly use all sorts of identity declarations to garner support for local public policies. The struggle for territorial control in partnership with the State and the designation of local leadership rest largely on the appeal of the notion of ‘dignity’ and ‘specificity’. These notions have become significant parts of the symbolic construction of a collective identity. Also, the educational system is forever the subject of debates concerning the inclusion of local ‘specificity’ to strengthen identity affirmation within the Guadeloupean and Martinican societies in their relations with metropolitan and European centers. In order to reinforce their legitimacy, some political leaders do not hesitate these days to embrace local identities while they claim at the same time to be part of political movements which are strongly marked by the tradition of assimilation. These cross-pressures put them at risk of moving away from the metropolitan parties.[xxi]

Each movement, in its own way, strives to mobilize support by identity construction-affirmation. ‘Civil society’ abounds with initiatives from groups or organizations whose strategies participate in the construction of collective identities. Whether they are movements engaged in defense of the environment or defense of the neighborhood, a retreat from specific micro-identities has taken place. These movements now often aim at participating in political forums during local elections.[xxii]

The phenomena of identity construction are also of concern to the West-Indian diaspora in Metropolitan France. In the 1960s and 1970s emigration to mainland France was quite strong. During the period of 1974-1982, departures amounted to 23,000 people or almost 3,000 people per year. This high rate of emigration enabled a large part of the natural population growth to be absorbed and explains the moderate increase in the population until 1982. From the 1980s, however, the French Antilles witnesses a contrary tendency. This development was a result of endemic unemployment in mainland France, but was also tied to the favorable civil service salaries in the overseas Départements in comparison with mainland France. Consequently, during the period 1982-1990, the net migratory balance was inverted to almost 1,900 arrivals per annum.

The demographic history of the Départements shows an impressive dynamic. One out of four West Indians born in the region now resides in metropolitan France. In 1999, their number (212,000) almost equaled the total population of Martinique (239,000) or Guadeloupe (229,000) in 1954. The population drain appears all the more remarkable when one bears in mind that mostly young and active people migrated. Out of every 100 West Indians who left their Département of origin to settle in metropolitan France in 1990, 75% were under 40 years old, and almost 65% were between 15 and 39. Almost half of the Martinicans aged between 30 and 40 years had settled in metropolitan France.[xxiii]

At present a large West Indian community exists in mainland France whose numbers are difficult to calculate due to poor census methods and the intermingling of generations: many people of Martinican or Guadeloupean descent living in mainland France were born there. We can roughly estimate that 500,000 West Indians and Guianans, across all generations, presently live in Metropolitan France, the large majority being made up of the Martinicans and Guadeloupeans (337,000 as of March 1999). Martinicans and Guadeloupeans living in France work for the most part in the public sector, in particular the post office and within the hospital system. In the West Indian diaspora in France a double affiliation, Antillean and French, is evident. Reports from the 1999 census tend to show stabilization, even a debit balance of migratory movements towards the mainland. This stabilization seems to be caused by a return of migrants of the second or even third generation. In the diaspora the French Antilles are internalized as an obligatory frame of reference, a myth sustained by the hope – especially for the West Indians of the first generation – of a hypothetical return to the home country. This framework integrates references borrowed from French society and emerges as a space of intense identity re-compositions. Consequently, the fact that Guadeloupean and Martinican migrants have been excluded from mainstream French society in spite of their citizenship has encouraged them to develop a strong consciousness of community identity and to mobilize a symbolic identity in order to enhance and defend their fundamental rights, especially the right to social promotion.[xxiv]

In other words, ethnic identity and its cultural attributes represent important political resources, since the ‘community’ emphasizes specific problems while celebrating differences within French society at the same time. West Indian emigrants are progressively changing in attitude and behavior within the metropolitan society. Whereas the pioneers – the immediate post-war emigrants, a minority coming from the middle classes and brought up with an ardent admiration for the Republics school system – aimed at integrating into the mainstream rather than singling themselves out, the West Indians who settled later in metropolitan France tended to voice a variety of specific demands. They condemn discrimination and their low presence in the political and cultural arenas as well as the cost of air transport between the West Indies and continental France. Hence they show a noticeable tendency to organize themselves into ‘demand groups’, or join political parties, trade unions and associations that are keen to defend their interests.

On the islands themselves, strong tensions sometimes occur between the local population and ‘foreigners’. These tensions particularly concern the Haitians who are rejected in Guadeloupe, and the Saint-Lucians in Martinique. In 2000, it was estimated that 22,000 migrants were present legally in Guadeloupe and 10,000 illegally (half of them solely in the commune of Saint-Martin).[xxv]

The number of documented Haitians in Guadeloupe amounted to 9,935 in the survey of 1999. Apart from the undocumented migrants whose number is difficult to establish, the migratory flow remains low, also when including the population of metropolitan origin. The example of Martinique (see Table 2) shows that in 1999 11% of the people residing on the island originated from outside, most of which came from metropolitan France.

Emigrants represent less than 1% of the total population of Martinique. The Haitians are the most numerous, but they are ten times less in Martinique than in Guadeloupe. They are followed by Saint-Lucians, and by citizens of EU member countries, other than France. Most Martinicans aver that the presence of the latter, which are benefiting from the principle of free movement within the EU, does not pose any problems because of their small number. That is not necessarily the same for the migrants coming from continental France. As a matter of fact, in view of high unemployment figures, some political movements and trade unions have tried to make the distinction between ‘Martinicans’ and ‘non natives’, particularly with regards to competition for jobs in the public service. Demands in favor of ‘west indianization’ of posts tend to amplify after economic downturns, based on an ‘affirmative action’ policy for Martinicans. More recently, similar demands have been made to secure jobs in the private sector.

Economics, Employment and Welfare

The economic model, prevalent in the French West Indies, operates on the basis of blending economic growth and development. Frequently, official reports underline the drawbacks of a model that does not enable the islands to achieve self-sustained development despite considerable economic growth. Some elementary statistics placed in their proper perspective reveal that the process of départementalisation from its inception to the present day has been instrumental to the political elite in attaining economic resources from the mainland in order to attain a high level of development.[xxvi]

The increase of GDP and revenues is assured by the mainland and, increasingly also by the EU (EU). Hence, there is a significant difference in economic conditions with the independent states of the Caribbean. These states do, indeed, benefit from foreign financial contributions in the form of aid, including aid from the EU under the Lomé Conventions (Cotonou Agreement, as of June 2000). But their situation cannot be compared to that of the French Antilles which are directly integrated into French and European frameworks, and which therefore benefit from significant public funds, an important factor in financing the local economy. The funds derived from the mainland and the EU constitutes one of the major driving forces of an economic growth rate that is often higher than in the mainland during identical reference periods. Such funds usually benefit households (civil servant salaries, social benefits, tax breaks) and, to a lesser extent businesses (grants, public contracts, tax incentives). With respect to civil servant salaries, it should be noted that since the 1950s these remunerations are 40% higher than those received in mainland France (including the institutions of the Municipalité, Région and Département) and related public administrative bodies. In other words, all civil servants enjoy advantageous benefits, independent of employment by the State public service or the collectivités territoriales or by the public hospital. Also the location of origin, West Indian or Metropolitan, does not make a difference in civil servant salary level.

Table 3 illustrates the total expenditures of the State in the Département Guadeloupe for the years 2001 – 2003. It appears that the deficit balance which corresponds to the State transfers to the Département varies from year to year, from Euro 470 millions in 2001 to Euro 558 millions in 2002. A similar observation can be established for Martinique: the debit balance was Euro 492 million in 2001 and Euro 423 millions in 2002.

A more precise picture of the total amount of social and public transfers in the two Départements requires that the balance payment of social transfers must be added to these figures (see tables 4 and 5). For example, in 2003 the total amount of social and public transfers in Guadeloupe was Euro 1160, 5 millions, Euro 470.5 millions brought in by the State, and Euro 1161,1 millions provided by the Social Bodies, and Euro 28,6 millions coming from other transfers (Banana subsidies).

Table 4 – Balance payment of public transfers in favor of Martinique 2000 -2002 (million Euro) Table 5 – Balance payment of public transfers in favor of Guadeloupe 2001-2003 (million Euro)

In addition, the increasingly important role played by another protagonist – the EU – should not be ignored. Martinique and Guadeloupe are ‘Outermost Regions’ (ultra peripheral regions) of the EU, which means that European legislation and policies may be adapted to their specific characteristics. In addition, their banana, sugar and rum markets benefit from protective measures against international competition. In particular, the DOM benefit from significant structural funds whose aim is to promote development and economic adjustment. The aid allocated by the EU amounted to a total of 1.2 billion French Francs between 1989 and 1993. These development funds were doubled and reached 2.5 billion French Francs by the year 2000. The new Structural Fund for the years 2000 – 2006 allocated Euro 805.5 millions to Guadeloupe and Euro 674 millions to Martinique. These substantial increases are supported by identical and complementary efforts of the State, territorial institutions and local actors, in particular through the State-Région five-year economic scheme and the ‘Single Planning Document’ (SPD).[xxvii] The following pie charts represent the financing of the ‘Single Planning Document’ for Guadeloupe and Martinique and the respective contribution of the participating institutions.

To these funds must be added the European funds contributed by the programme INTEREG[xxviii] III-b, which aims for a better integration of Guadeloupe and Martinique (as well as French Guiana) in the Caribbean region. For the period 2000-2006, these funds amount to Euro 24 million for the Antilles and Guiana, of which 12 million comes from the EU’s European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

It would be difficult to total together all these diverse funds that cover policy areas as disparate as sustainable development and maintaining the collectivités territoriales, in order to calculate the amount of State and EU public and social transfers towards the French West Indies, and so establish a ratio per inhabitant. Nevertheless, one thing is sure, these transfers play a fundamental role in the insular economies. For example, one estimate suggests that net public transfers of the French state to Martinique amount to roughly one quarter of its total GDP.

As a result of the process of institutional assimilation, an economic development model has emerged that makes Martinique and Guadeloupe stand out against the other territories in the region. The French Antilles present a most notable economic development index within the Caribbean. This singular characteristic requires some explanation. The transformation of the French Caribbean islands into French Départements in 1946 raised enormous expectations with regards to social and economic development. Founded in the universalistic ideals that characterised the French State, economic and social ‘assimilation’ of the ‘Four Oldest Colonies’ with mainland French became a notion that matched perfectly the local ambitions to bring an end to underdevelopment that contradicted the Republican ideal of equality. With the benefit of hindsight, it may seem foolish today to try to solve the intractable set of social and economic problems that beset the former colonies merely by applying a few Keynesian principles that were thought at that time to have universal value. Increased public spending, development of infrastructure and a system of financial incentives were the measures put in place to achieve an objective that hardly has changed: matching the standard of development present in mainland France. Each and every attempt was inspired by the inescapable, but flawed logic that matching economic conditions could be achieved with the help of massive injections of public funds into the island economies.

This was the case in re-building traditional agricultural sectors like sugar cane and bananas during the period 1946-1960, or in establishing an administrative apparatus modeled on the system in mainland France in 1961, or in creating economic and local authority structures with direct funding from the ministries in Paris. This strategy had crucial repercussions as it undoubtedly fuelled remarkable levels of economic and social development in Guadeloupe and Martinique, which together demonstrate a showcase for France and Europe in the Caribbean.

However, the economic output needs to be qualified, taking into account the persisting structural imbalances that have marked this development model. As generous as it may seem, this determined approach presented several unexpected and perverse effects. The priority given to the ‘catching up’ objective resulted in relatively high economic growth from 1946, which at times was even higher than in mainland France – an average of 4% per annum between 1975 and 1994[xxix] – but this was highly dependent on public fund transfers and entailed a deterioration in local production capabilities.

Unemployment is now a serious problem on both islands; it affects more than 25% of the working population and is reinforced by other forms of under-utilization of the available labor force. Unemployment is endemic and many people do not bother to seek employment; they depend on social allowances.

The importance of the Revenu Minimum d’Insertion (Minimum Integration Income) (RMI) in the two islands is obvious. The number of beneficiaries in 2002 in Guadeloupe was 29,764 and in Martinique 31,436. Ever since its creation in 1989 the RMI has become a means of subsistence for a growing part of the Martinican and Guadeloupean population. The number of direct beneficiaries in the overseas Departments, including the French West Indies, represented 15% of the population as compared to 3.1% in metropolitan France.[xxx] Designed to supplement the deficiencies of the welfare system, the RMI offers certain groups that face financial difficulty the opportunity to benefit from specific integration measures. But the actual result has been that the RMI supports a sector of the population that suffers from endemic labor market exclusion.

Those benefiting from this allowance are mainly young people: 52% are younger than 35 years and 24% are between 35 and 44 years of age.[xxxi] These figures demonstrate the difficulties that young people, who are particularly affected by long-term unemployment, encounter when trying to get into the job market. The failure of numerous political measures to enhance employment, some of which have been specially designated for the overseas Departments, have demonstrated the limitations of positive action in the face of an economy that is unable to accommodate a young population.[xxxii] The plans designed for them allow at best a respite of some months or some years before they fall back onto the guaranteed RMI. Eventually this allowance is the only income for a majority of young beneficiaries who have never worked, or have only done so for a brief period, and who are unable to obtain regular employment.[xxxiii] Wanting to escape this vicious cycle is therefore not a realistic option.

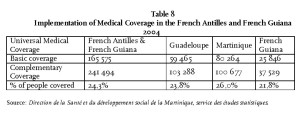

For the DOM, the drawbacks of such a development model are offset by a generous welfare system. One of the objectives of the process of départementalisation was to enable the former colonies to benefit from all rights inherent in French citizenship, in particular with regards to social provisions. In 1996, fifty years after the law of assimilation was enacted, social equality of the DOM with mainland France was proclaimed. Now the population receives all the social provisions that are in force in France. As of the early 1990s, the departmental funds for social aid began once more to rise following a slump that had coincided with the period of decentralization.[xxxiv] This evolution – a dramatic rise in social aid granted by the Département after a respite in the 1980s – reveals the universalistic pretensions of the system of social security. Since 2000, Universal Medical Coverage (CMU) is included.[xxxv] It appears that in the DOM the number of beneficiaries of the social services – particularly the RMI and the CMU – is proportionally much higher than in metropolitan France: in 2002, 26% of the Martinican population and 23.8% of the Guadeloupean population benefited from the CMU, compared to 7.5% for the population of continental France.

Education

Long before Martinique and Guadeloupe became full-fledged Départments of France, education was considered a priority. But there remained much to accomplish. In 1900 for example, Martinique counted approximately 13,000 children (6,830 boys and 5,158 girls) in primary school out of a total of 62,000 school-aged children. The level of exclusion was much higher in the countryside, due to children working on the plantations, with nearly three-quarters remaining illiterate or uneducated.[xxxvi] While secondary education was a luxury that only a few children from privileged families could afford.

In 1946, at the time when the départementalisation process was launched, the public primary school sector included 40,018 pupils against 2,090 in the private school system; secondary schools had 3,962 students enrolled and 721 were enlisted in vocational education programmes.[xxxvii] In 1971, 25 years later, primary school enrolment had doubled, reaching 88,024 pupils; secondary school figures remained stable at 3,150. However, in the first cycle of general education and in specialized education middle schools the number enrolled jumped to 24,307, and enrollment for vocational education tripled (2,400). In 1971, almost 700 Martinican students were registered with mainland French universities and 327 at the faculty in Martinique.[xxxviii]

The Martinican and Guadeloupean public enjoys a relatively high level of education. The educational infrastructure established over the past few decades has enabled substantial improvement to occur. The rate of enrollment in primary schools is 100%; while enrollment has constantly increased in secondary schools and jumped from 17% in the 1960s to over 46% in the 1990s. The proportion of young people enrolled in school at age 16 in Martinique as well as Guadeloupe is higher than in mainland France.[xxxix]

Without any doubt, these results are in line with the expectations of a major part of the population that perceives education in terms of cultural capital and social progress. These results also reflect the objectives set by the State to make education one of its main priorities within the framework of em>départementalisation. The ambition of creating a tertiary sector within the Martinican and Guadeloupean economy has encouraged these efforts. This sector includes a vast potential for human resources, compensating for the low level of natural and material resources. The progress in education reflects par excellence the ideology of an egalitarian Republic which aimed to close the gap that existed with the mainland and has thus fostered claims in favor of an increased intervention by the French central government and amplification of the flow of public fund transfers.

However, this irenic vision must be tempered in view of the large proportion of youths who have completed their studies and subsequently face enormous difficulties once they find themselves ready to enter the job market. The low rate of first employment demonstrates the setbacks that are prevalent in the labor market. Such imbalances can be traced back to the confines of the French Antilles status as overseas Département, which is principally based on an artificial economic growth generated by public and social fund transfers.

The Rule of the Law and Democracy

Formally integrated within the French and European orbit, the French West Indies are subject to the principles of the rule of law: government authority is exercised in accordance with written laws, which are adopted through an established procedure. Individuals and government are subject to law, and all individuals have equal rights without distinction in regard to social stature, religion, political opinions, and so forth. This equality principle is especially significant in countries where the colonial past still holds a strong grip on the collective consciousness. Here the formal dimension of the rule of law is confronted with the conditions under which citizenship was granted. The historical short cut with regards to the successive components of citizenship – civil, political and social – continues to affect the relationship of the overseas citizens under the law and with the State. It affects also the capacity of the French republican universalism to call into question local allegiances or to reduce the institutional specificities inherited from colonialism.

The implementation of the départementalisation process resulted, at least in the beginning, in a complex combination of old and new structures which were partially reinterpreted. The colonial past continued to prey on the collective imagination in the context of a growing centralization and standardization in the DOM.[xl] These local predispositions gave rise to demands that specificities be respected, that internal autonomy be reinforced and that law enforcement be adapted to the local situation. In a more general way, the deepening of institutional assimilation did not entail the disappearance of traditional forms of allegiance to organizations and informal practices that coexisted with legal norms emanating from the central government.[xli] The citizenship allegiance that was created with the départementalisation process, became adapted to these pre-existing residual and unofficial organizations and informal practices, which demonstrates the limits of State penetration into an external and distant outermost region where cultural difference is regularly emphasized. The operation of the local political administrative system in Martinique highlights the phenomena of the transgression of civil servants rules. For instance, the Prefect tends to interiorize the norms of the island society and adapts them to local contingencies. Despite the persistence of centralization, the Prefect sometimes becomes an advocate of local interests. The insular society thus avenges itself of State imposed centralization and standardization. In other words, le mort saisit le vif.[xlii] The combination of these elements demonstrates that the assimilationist claims collide with local aspirations whereas the republican universalism continues to serve as the foundation of equality. In such a context, tensions between the universalism proclaimed by the State and a locally fostered identity, may become acute. In other words, the départementalisation of Guadeloupe and Martinique did not completely overrule the allegiance to a dual system of universal and particularistic norms.

As for democracy in the DOM, a crisis of the representative institutions is apparent. This is indicated by: a profusion of candidates on all the ballots, an erosion of the traditional political forces, the rise of peripheral competing forces and, with the exception of the municipal elections of 2001, a decline in participation.[xliii] The rates of abstention in the first round of the presidential election in 2002 speak for themselves: 65.9% in Guadeloupe and 64.6% in Martinique. This crisis apparent in representative democracy, combined with the process of Antillean political movements distancing themselves from their counterparts and traditional allies on the mainland, has altered the political realm. The process of territorialisation of the political forces, which was initiated in the late 1950s by the left and recently accelerated, now affects all political movements, regardless of their political label or persuasion. These phenomena – a crisis in representative democracy, a distancing from metropolitan political life, and the rise of identity assertions – are mutually consolidating.

Crime and Diplomacy

The French Antilles are not immune to an alarming tendency evident in the whole of the Caribbean region, which is the dramatic and regular increase in crime and the feeling of insecurity that has emerged over the last few years. Certainly, the statistics must be used with caution since insecurity is one concept that is rather predisposed to manipulation. Nevertheless, the statistics reveal a quantitative and qualitative evolution of crime in Guadeloupe and Martinique.

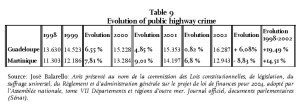

The evolution of public highway crimes (armed robbery, robbery with violence, burglary, car theft, theft from vehicles, and criminal destruction and damage) has developed since 1998, as table 9 shows.

From a qualitative point of view, violent crime has increased dramatically in both islands. In Guadeloupe, armed robberies multiplied by three between 1993 and 2003, while crimes and offences against the person doubled. In Martinique, armed robberies increased by 200 % over two years. The qualitative change in crime is related to the development of drug addiction. Without being high traffic stations, Guadeloupe and Martinique are spaces of transit. An increasing local consumption affects the entire society. It is evident that the borders of these two islands are relatively porous and increasingly difficult to control.

Security is ensured by the French State in charge of the sovereign mission of government. France operates today in large measure within the framework of the EU, which favors a new regionalism in structuring a partnership between the territories of the Caribbean and the EU. The EU external borders extend to the Caribbean, due to the incorporation of the French West Indies. This is especially true in the struggle against the drugs trade and money laundering, where broad cooperation is required among the various countries of the Caribbean, the countries of the EU that are directly involved in the region, and the United States. These convergent interests initiated the establishment of the Bridgetown Group in 1990, a regional counterpart to the EU parent Dublin Group.

The Bridgetown Group meets monthly on an informal basis and representatives of British, Canadian, French and US diplomatic missions attend together with officials from the EU, the Organisation of American States and the United Nations. A similar group has been established in Trinidad.[xliv] Martinique and Guadeloupe have become significant sites of coordination in the fight against narco-trafficking and money laundering. The mobilization of state services, a regular exchange of information and technical and financial assistance between governments has encouraged a common approach to combating drug trafficking. However, there is a problem with regards to the competences of the State and the local authorities.

Regional Cooperation

At present local councilors consider engagement in regional co-operation a political challenge. Their discourse on co-operation between the French West Indies and their neighbors is not new but the rather limited results when offset against highly vocalized ambitions, give these efforts an incantatory character. Elected officials at the head of decentralized institutions are keen to denounce the legal and political obstacles that prevent better integration of the French Antilles within the Caribbean area.[xlv] The French government does not remain indifferent. Beginning with measures taken by the Rocard government in the early 1990s to the recent provisions of the loi d’orientation pour l’outre mer (LOOM), the institutional arrangements for regional co-operation improved notably.

The presidents of the regional and general councils have been endowed with a ‘representative role’ in the Caribbean by granting them the power to negotiate agreements with one or several neighboring states and territories, or regional organizations. These presidents now also have the capacity to negotiate and sign agreements with partners and to take action within their domain of competence. In addition, the LOOM Act allows local executives to represent France in international forums of a regional nature, such as the Association of Caribbean States (ACS). Lastly, the LOOM regulation created several funds for co-operation, mainly financed by the State and to which subsidies from the EU are added, either within the framework of the European Regional Development Fund or within the framework of the program INTEREG IIIB ‘Caribbean Area’. This institutional framework favors the development of cooperation in economic, scientific, technical, cultural and sporting domains.

It is still too early to assess the long-term effects of the improved arrangements for regional cooperation, in particular the recent provisions contained in the LOOM Act. The outcomes of cooperation cannot be evaluated simply through reviewing legal measures or decisions made by official institutions. Also to be taken into account are the regularity of cooperation practices; the behavior of the population and their capacity to appropriate this cooperation; and, finally, the capacity of the elected officials to stimulate and oversee public and private initiatives. From this perspective regional cooperation is far from complete.

Conclusion

Guadeloupe and Martinique underwent an original historical trajectory from the status of being a colony to one of an overseas Département formally integrated into the French national concord. In a long experience shared with mainland France, départementalisation resulted in changes influencing all aspects of insular social organization. At the political level it gave rise to the imposition on these distant islands of institutions identical to those functioning in mainland France, though with some minor amendments. Likewise, laws and regulations enacted in Paris were automatically applicable and the French West-Indian citizens remained much attached to the principle of republican equality. Such a system, however, reveals its limitations today. Based on the French tradition of centralization of power, the départementalisation project has gradually run out of steam. It hardly succeeds in taking into account demands that have emerged, in particular the persistent claims to the right to enjoy one’s own culture. These calls are fed by identity assertions and reveal one of the major paradoxes of départementalisation. The economic, social and political bonds with France have been strengthened during the last years, but at the same time the cultural bonds have been loosened and a withdrawal from French identity has taken place on both islands.

A number of issues illustrate the current ambiguity in the relationship between Martinique, Guadeloupe and mainland France. On the one hand, on each island strong indigenous cultural movements manifest themselves and a valorization of local resources is apparent. The recent election of a strong supporter of independence as head of Martinique’s regional government also points to nationalistic sentiments. On the other hand, both DOM have recently rejected plans to simplify their organisational structures as they feared that such would put their close ties with France and Europe at risk. And since the end of the 1980s, the independence movement as such has lost much of its appeal on Guadeloupe. The French West Indies show a paradoxical concurrence of cultural nationalism on one hand and a weakened appeal of political independence on the other. In short, the French West Indies offer a perfect example of cultural and political identity being dissociated from each other.

From an economic point of view, the situation is equally complex. The two islands have reached a level of development that in many respects comes close to the level in developed countries. But the model implemented in 1946 had unexpected and persistent effects. The quest for social equality and a high standard of living has penalized the productive sectors, in particular by increasing production costs. Further, the French West Indies have become isolated from its regional economic environment. Mainland France as well as the EU is condemned to socialize the consequences brought about by the choices made in 1946. Public and social transfers regularly rise in volume. These financial contributions maintain a very strong dependence on external resources and limit the possibilities of implementing an economic model in Guadeloupe and Martinique based on sustainable development. Thus a deep social malaise in particular due to endemic unemployment, has set in. The social fabric is fraying, evidenced by new forms of criminal activity, which are related to the increased consumption of drugs. The explosion of cultural activities expresses both a protest against the French model of assimilation, and a quest for Antillean identity. As a result, demands for a change in political status fuel a permanent public debate. These demands are linked to notions of ‘democracy of proximity’ and to identity assertions. The quest for republican equality with a strengthening of political autonomy and one’s own cultural rights is difficult to reconcile within a coherent political framework.

NOTES

i. However, the notion of assimilation, while affirming its universalist dimension, proved, at least at the beginning of the colonial period, to be compatible with the maintenance of a colonial regime founded on a hierarchical organization and a very pronounced differentiation.

ii. Boissy d’Anglas (François Antoine de) is a moderate politician who served during the French Revolution, the Empire, and the Restoration. His political philosophy was firmly based on religious tolerance, freedom of expression, strong constitutional government and equality before the law.

iii. M. Giraud 1997.

iv. R. Suvélor 1983.

v. M. Mauss, 1999.

vi. In mainland France, since 1964, the départements have been grouped into 22 régions as a result of the policy of decentralization of local government.

vii. These decrees provide for the consultation of the local assemblies before the implementation of laws in the overseas departments.

viii. The régional council is the elective assembly of the région; the géneral council is the elective assembly of the département.

ix. Since the départementalisation process, a single Martinican was appointed to the office of Prefect in Martinique.

x. While local government in France has a long history of centralization, the past 20 years have brought some radical changes. The decentralization law of 2 March 1982 and the legislation completing it marked the Paris government’s desire to alter the balance of power between the State and local authorities (regions, departments and communes). It gave far greater autonomy in decision-making by sharing administrative and budgetary

tasks between central and local authorities. The March 1982 law also made several changes concerning financing. Any transfer of State competence to a local authority must be accompanied by a transfer of resources (chiefly fiscal). In practice, local taxes have tended to rise. The reform also extended the responsibilities of the communal, départemental and regional accountants, giving them the status of chief accountant directly responsible to the treasury. Lastly, the 1982 law assigned to a new court, the regional audit chamber, and responsibility for the final auditing of local authority accounts. The process of decentralization has profoundly altered local government in France. The new system is indisputably more costly than the old for the public purse and has led to some fragmentation of tasks and objectives, as local authorities act primarily in their own rather than the national interest. In March 2003, a constitutional revision has changed very significantly the legal framework and could lead to more decentralization in the coming years. See Association des maires de France:

http://www.citymayors.com/france/france_gov.html

xi. The difference between the two islands is explained by higher social transfers in Guadeloupe (2,696 Euro per inhabitant as against 2,000 Euro for Martinique), owing to a higher degree of poverty.

xii. Her conduct of public affairs was controversial, due to corruption and an autocratic exercise of power.

xiii. T. Marshall 1997.

xiv. P. Rosanvallon 1993.

xv. F. Constant 2000; J. Daniel 1997.

xvi. D-C. Martin and B. Jules Rosette 1997.

xvii. J. Daniel 1997.

xviii. M. Giraud 1997: p. 385.

xix. Y. Bernabé et alii.

xx. F. Constant 1993.

xxi. A former Member of the French parliament, Pierre Petit, embodies, along with other

politicians, this strategy.

xxii. J. Daniel 2001.

xxiii. C-V. Marie 2002: p. 27.

xxiv. M. Giraud 2002.

xxv. J. Larché et alii, 2000.

xxvi. J. Daniel 2001.

xxvii. The SPD is a planning document that collects the financial funds from the EU, the State and the territorial institutions. It serves as a six-year guide of public interventions.

xxviii.The program is specifically designed to help promote greater economic, social and regional cohesion and integration in the cooperation area, particularly with neighboring countries and regions, in order to bring about sustainable, balanced development. These aims are in line with the economic integration objectives for the area proposed under the regional programs of the European Development Fund (EDF). Cooperation with neighboring countries and regions will have to be coordinated closely with organizations working in the area, particularly the Association of Caribbean States and the Caribbean Forum. (European Commission: http://europa.eu.int/comm/regional_policy/country/prordn/details.cfm?gv_PAY=IT&gv_reg=A LL&gv_PGM=2001CB16PC009&LAN=5).

xxix. This tendency has been maintained during recent years, even if the contribution of the private sector to the growth of GDP seems to have increased in value. The GDP of Guadeloupe has grown on average by 4.90% per annum from 1993 to 2000, compared to 4.92% for that of Martinique during the same period (IEDOMb, 2003: 37).

xxx. Fragonard et alii, 1999, p. 41

xxxi. IEDOM 1998: p. 18.

xxxii. M. Carole 1999.

xxxiii. IEDOM 1998: p. 19.

xxxiv. This decrease is mainly explained by the efforts deployed by the Département of Martinique to limit the expenditure of social aid. But from the beginning of the 1990s, the economic and social situation once again deteriorated, bringing with it a new increase in social expenditure.

xxxv. These categories are mainly unemployed or underemployed persons who do not receive unemployment benefit. See Daniel and Dokoui, 2003.

xxxvi. A. Nicolas 1996: p.155.

xxxvii. A. Nicolas 1998: p. 133.

xxxviii. Idem: p. 278.

xxxix. C. Lise and M.Tamaya 1999: p. 14.

xl. We refer in particular to the prefectorial institution that was perceived at the beginning to be the resurgence of colonial rule.

xli. The most significant example is the informal economy. See, for example, K. Brown.

xlii. J. Daniel 1984.

xliii. The decline in participation is general and concerns almost all elections: – Legislative elections: the abstention climbed from around 38% in 1967 to 53% in 1993; this rate is close to that noted for the cantonale elections in the large communes or in Fort-de-France – The regional elections are equally characterized by a regular and notable increase of abstention: less than 39% in 1983 compared to 52% for the first round in 2004 (the record being attainted in 1998 with 55%); – The referendums: rates of abstention of 39% in 1961 (self-determination in Algeria), 62.42% in 1972, 87% in 2000; – The presidential elections have undergone a constant increase of the rate of abstention since the beginning of the Fifth Republic: 1965: 34.87%; 1969: 53.2%; 1974: 46.14%; 1981: 51.65%; 1988: 42.37%; 1995: 59.23%; 2002: 64.62%.

xliv. P. Sutton 1995: p. 51.

xlv. They denounce a very restrictive mode of delivery for visas, which is due in particular to the fight against clandestine immigration and the limited competence granted to local officials.

Bibliography

Bernabé, Y. & Capgras V. & Murgier P, Les politiques culturelles à la Martinique depuis la décentralisation. In: Fred Constant & Justin Daniel (eds), 1946-1996: Cinquante ans de départementalisation outre mer, Paris: L’Harmattan, 1997, pp. 133-151.

Browne, K. E., Creole economics: Caribbean cunning under the French flag, 1st ed, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004.

Carole, M., Les politiques et mesures d’aide à l’emploi: une priorité, Antiane-éco, 41, June 1999, pp. 24-25.

Constant, F., Les paradoxes de la gestion publique des identités territoriales: à propos des politiques culturelles outre mer. In: Revue française d’administration publique, 65, 1993, pp. 89-99.

Constant, F., La citoyenneté, Paris: Montchrestien (Clefs Politique), 2000.

Daniel, J. & Dokoui S., L’introduction de la couverture maladie universelle à la Martinique. Rapport remis au ministère de l’outre mer en avril 2003, Fort-de-France, 2003.

Daniel, J., L’espace politique martiniquais à l’épreuve de la départementalisation. In: Fred Constant F. and Daniel J. (eds), 1946-1996 Cinquante ans de départementalisation outre mer, Paris: L’Harmattan, 1997, pp. 223-259.

Daniel, J., The construction of dependency: Economy and Politics in the French Antilles. In: Aaron A. G. and Rivera A. I. (eds), Islands at the Crossroads. Politics in the Non-Independent Caribbean, Kingston, Jamaica; Boulder, Co.: Ian Randle Publishers; Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001, pp. 61-79.

Daniel, J., Development policies in the French Caribbean: from State centrality to competitive polycentrism. In: Bissessar A. M. (ed.), Policy Transfer, New Public Management and Globalization. Mexico and the Caribbean, Lanham: University Press of America, 2002, pp. 97-113.

Fragonard, B. et alii. Les départements d’outre mer : un pacte pour l’emploi, Rapport remis à Monsieur le Secrétaire d’Etat à l’outre mer, Paris, 1999.

Giraud, M., De la négritude à la créolité: une évolution paradoxale à l’ère départementale. In: Daniel J. and Constant F. (eds), 1946-1996: Cinquante ans de départementalisation outre mer, Paris: L’Harmattan, 1997, pp. 373-403

Giraud, M., Racisme colonial, réaction identitaire et égalité citoyenne. Les leçons des expériences migratoires antillaises et guyanaises. In: Hommes & Migrations, no. 1237 (Diasporas caribéennes), 2002, pp. 40-53.

IEDOM, Rapport de 1998, Fort-de-France. 1999.

IEDOMa. La Guadeloupe en 2003. Rapport annuel. Paris, 2004.

IEDOMb. La Guadeloupe en 2003. Rapport annuel. Paris, 2004.

Larché, J. et alii, Rapport d’information n° 366 fait au nom de la commission des Lois constitutionnelles, de législation, du suffrage universel, du Règlement et d’administration générale, JO, Documents parlementaires, Sénat, session ordinaire 1999-2000, Annexe au procès verbal de la séance du 30 mai 2000.

Lise, C. & M. Tamaya. Les départements d’outre-mer aujourd.hui: la voie de la responsabilité. Rapport au Premier minister. Paris: la Documentation française (Collection des rapports

officiels), 1999.

Marie, C-V., Les Antillais en France: une nouvelle donne. In: Hommes & Migrations (Diasporas caribéennes), no. 1237, 2002, pp. 26-39.

Martin, D-C. & Jules-Rosette B, Cultures populaires, identités et politique. In : Cahiers du CERI, no. 17, 1997.

Mauss, M., Sociologie et anthropologie. Paris: PUF (Quadrige), 1999.

Nicolas, A., Histoire de la Martinique. De 1848 à 1939. Vol. 2. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1996.

Nicolas, A., Histoire de la Martinique. De 1939 à 1971. Vol. 3. Paris: L’Harmattan, 1998.

Rosanvallon, P., L’État en France de 1789 à nos jours. Paris: Éd. du Seuil (Points Histoire 172), 1993.

Sutton, P. K., The ‘new Europe’ and the Caribbean. In: European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 59, 1995, pp. 37-57.

Suvélor, R., Eléments historiques pour une approche socio-culturelle. In: Les Temps Modernes, 39, no. 441-442, 1983, pp. 2174-2208.