ISSA Proceedings 2014 ~ The Study Of Reasoning In The Lvov-Warsaw School As A Predecessor Of And Inspiration For Argumentation Theory

No comments yetAbstract: The hypothesis proposed in this paper holds that the Polish logico-methodological tradition of the Lvov-Warsaw School (LWS) has a chance to become an inspiring pillar of argumentation studies. To justify this claim we show that some ideas regarding classifications of reasoning may be applied to enrich the study of argument structures and we argue that Frydman’s constructive account of legal interpretation of statutes is an important predecessor of contemporary constructivism in legal argumentation.

Keywords: classifications of reasoning, argument structures, schemes for fallacious reasoning, legal constructivism, the Lvov-Warsaw School

1. Introduction

The motivation for this paper lies in exploring possible applications of the heritage of the Lvov-Warsaw School (LWS) in argumentation theory. After presenting a wider map of current research strands and future systematic applications of the LWS tradition in contemporary argument studies (Koszowy & Araszkiewicz, 2014), in this paper we focus on the study of reasoning as one particular area of inquiry which constituted the core concern of the LWS. The main justification of the need of focusing on the inquiry into the nature of reasoning in the LWS is twofold. Firstly, it manifests clearly that apart from purely formal accounts, the School elaborated the broader pragmatic approach to reasoning which may be also of interest for argumentation theorists. Secondly, it may be particularly inspiring for contemporary argument studies because of the possibility of applying it in (i) argument reconstruction and representation and (ii) identifying the structure of fallacious reasoning.

The research hypothesis proposed in this paper holds that the Polish logico-methodological tradition of the Lvov-Warsaw School (LWS) has a chance to become an important theoretical pillar of contemporary study of argumentation. This hypothesis may be justified by undertaking systematic inquiry which would show that some key ideas of the LWS may be applied in developing some crucial branches of the contemporary study of argumentation. In order to argue that such an inquiry is a legitimate research project, we will show that apart from the developments of formal logic which are associated with the works of such outstanding logicians and philosophers as Tarski, Leśniewski or Łukasiewicz, in the LWS there was also present a strong pragmatic movement which may be associated e.g. with the works of Ajdukiewicz. Moreover, our aim is also to show that even ‘purely formal’ approaches to reasoning (e.g. the theory of rejected propositions proposed by Łukasiewicz) may turn out to be inspiring for argument analysis and representation.

In this paper, we will discuss two areas of applying ideas of LWS: argumentation schemes and legal argumentation. The aim of the paper will be accomplished in following steps. In section 2 we will sketch an outline of those research areas in the LWS which might be particularly interesting for argument studies. This preparatory discussion will constitute an introduction to Section 3 which is aimed at discussing the issue of applicability of LWS ideas regarding classifications of reasoning in argument representation. In Section 4, we will discuss the second area of applying the tradition of LWS in the study of argumentation is the domain of legal argumentation. We will argue that Frydman’s constructive account of legal interpretation of statutes (1936) is an important predecessor of a contemporary view in theory of legal argumentation referred to as constructivism and advanced for instance by Hage (2013). Finally, in the concluding section, we will sketch an answer to the question of how the two specific contexts discussed in the paper form a good starting point for a broader research project concerning application of methods and ideas developed in the LWS to contemporary open problems of argumentation theory.

2. Key research strands in the LWS from the point of view of argument studies

The Lvov-Warsaw School was ambitious philosophical enterprise (1895-1939) established by Kazimierz Twardowski in Lwów (see Woleński, 1989, Ch. 1; Lapointe, Woleński, Marion & Miskiewicz, 2009, Eds.). It is depicted as ‘the most important movement in the history of Polish philosophy’ (Woleński, 2013) the development of which is associated with ‘the golden age of science and letters’ in Poland (Simons, 2002). Despite of the fact that the heritage of the LWS is most famous for the developments of formal logic, thanks to such thinkers as Łukasiewicz, Leśniewski, Tarski, Sobociński, Mostowski, Lejewski, and Jaśkowski, it also encompasses a great variety of ideas in almost all fields of philosophy, including epistemology, ontology, philosophy of language, philosophy of argument, methodology of science, legal theory, ethics and aesthetics (e.g. Woleński, 1989; Jadacki, 2009; Woleński, 2013).

It might be a matter of some interest that the logical studies within the LWS focused not only on formal logic, but the school also developed the strong pragmatic approach to logic (Koszowy, 2010; Koszowy, 2013; Koszowy & Araszkiewicz, 2014). Note that even those representatives of the LWS who may be considered as ‘purely formal logicians’ also shared their interest in practical applications of logical theories. A clear illustration of this ‘pragmatic thread’ is Tarski’s view on employing logic in everyday communication. In the preface of the 1995 edition of his Introduction to Logic and to the Methodology of Deductive Sciences, Tarski points to two ideas of this kind:

(i) logical foundations of successful communication – as logic makes the meaning of concepts precise in its own field, and stresses the necessity of such a precision in other areas, and hence leads to “the possibility of better understanding between those who have the will to do so”, and

(ii) logical foundations of identifying fallacious reasoning – as logic perfects and sharpens the tools of thought and therefore it makes people more critical and “thus makes less likely their being misled by all the pseudo-reasonings to which they are in various parts of the world incessantly exposed today” (Tarski, 1995, p. xi). The latter point raised by Tarski also gives a ‘practical’ reason why the systematic study of reasoning (and of typical fallacies involved in it) constituted the core concern of the logical studies in the LWS.

An example area of possible applications of the LWS heritage in the study of argument structures is Bocheński’s analyses of One hundred superstitions (dogmas) (1994). Major affinities between this account and argumentation theory were earlier discussed in (Koszowy and Araszkiewicz, 2014, pp. 290-292). In order to emphasize the pragmatic dimension of Bocheński’s approach let us only note that his main concern was to help people to recognize those communicative mechanisms which are commonly employed in the social sphere in order to convince people to accept false beliefs. The broad program of detecting common errors in thinking and communicating may be seen in the fact that superstitions and dogmas are not only described by Bocheński from the inferential perspective (which focuses on detecting errors in reasoning), but also from the dialogical point of view (which consists of identifying typical moves in the dialogue employed in spreading superstitions in the social sphere), as well as within the rhetorical approach (that rests on analysing utterances aimed at convincing someone to accept a superstition).

Since this example may be helpful in exposing some general affinities between the LWS and argument analysis and evaluation, in what follows we will focus on answering the question: to what extent the accounts of reasoning in the LWS may be employed in the contemporary study of argumentation? The answer will be given by providing key reasons for the claim that amongst a variety of possible ways of influencing science and philosophy, the LWS has a chance to enrich the state of the art in the study of argumentation in two fields: (i) argument structures and (ii) legal argumentation.

3. The structure of arguments

Classifications of reasoning constituted the key subject-matter of inquiry in the LWS (Woleński 1988). The main goal of this section is to expose some methodological ideas related to classifications of reasoning proposed by Łukasiewicz, Czeżowski and Ajdukiewicz which may be instructive in reconstructing arguments.

Łukasiewicz, Czeżowski and Ajdukiewicz attempted to develop their own classifications which were, amongst some other goals, aimed at achieving a better understanding of the complex phenomenon of reasoning and of the typical kinds of reasoning as applied in science and in philosophy. Two main approaches to classifying reasoning were proposed by (1) Łukasiewicz[i] (and continued by Czeżowski), and (2) Ajdukiewicz. Whereas Łukasiewicz and Czeżowski focused on the formal-logical aspect of reasoning, the classification elaborated by Ajdukiewicz’s took into account not only formal characteristic of reasoning, but also its substantial pragmatic features – what was in line with his program of ‘pragmatic methodology’ (Ajdukiewicz, 1974, pp. 185-190; see also Woleński, 1988, p. 24). Despite of the fact that these two lines of classifying reasoning differ from each other, both of them consist of some intuitions which may be turn out to be inspiring for those argumentation scholars who focus on argument structures.

Some particular applications of the legacy of the LWS in the research on argument analysis and representation were exposed by Trzęsicki (2011). In this work we may find two ideas constituting the heritage of the LWS that might turn out to be particularly useful in representing the structure of arguments: (1) the distinction between accepted and rejected propositions and (2) the distinction between the direction of entailment and the direction of justification.

The first idea rests on developing argument diagramming method which employs the distinction between four kinds of propositions:

(i) asserted,

(ii) rejected,

(iii) suspended, and

(iv) those which are neither asserted, nor rejected, nor suspended (Trzęsicki, 2011, pp. 59-60).

What might be a matter of particular interest for the project aimed at incorporating this distinction in argument representation and analysis is the possibility of applying Łukasiewicz’s account of rejected propositions (Łukasiewicz, 1921; see also Słupecki et al., 1971; 1972) in argument diagramming.

Łukasiewicz (1921; see Słupecki et al., 1971, p. 76) noticed that the modern formal logic did not use ‘rejection’ as an operation opposed to ‘assertion’. Note that even the very justification of the study of rejected propositions given by Łukasiewicz might be of interest for those who study ancient roots of argumentation theory. According to Łukasiewicz, Aristotle’s idea of rejection, which has never been properly understood, “could be the beginning of new logical investigations and new problems which should have been solved” (see Słupecki et al, 1971, p. 76). This intuition concerning the need of the study of rejected propositions in formal logic is in accordance with the need of representing those argumentative moves (such as attacks, undercuts and rebuttals) which result in rejecting claims that have been put forward in argumentation. Although Łukasiewicz employed his distinction between asserted and rejected propositions in the context of research in formal logic, as we will show, there is also a possibility of employing it also in the field of argument representation.

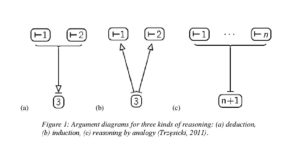

The second idea elaborated within the LWS which also plays a key role in representing argument structures is the distinction between the direction of justification and the direction of entailment. This distinction has been employed within the diagramming method proposed by Trzęsicki (2011). For example, this method allows to represent the structures of typical kinds of reasoning such as deduction, induction and the reasoning by analogy:

Figure 1: Argument diagrams for three kinds of reasoning: (a) deduction, (b) induction, (c) reasoning by analogy (Trzęsicki, 2011).

We may here observe how the previously discussed intuitions regarding classifications of reasoning are present in argument diagrams. In these three example diagrams, the numbers 1, 2, etc. represent propositions which have been extracted from the particular text. In the above diagrams all propositions are asserted, however this method also allows us to distinguish all four types of sentences: (1) asserted (e.g. ├1, ├2), rejected (e.g. ┤1, ┤2), suspended (e.g.├┤1, ├┤2) and those which are yet neither asserted nor rejected nor suspended (and which are represented by numbers of propositions without any additional symbols, e.g. proposition 3 in diagrams (a) and (b)). The direction of entailment is represented by an arrow, whereas a perpendicular dash denotes the direction of justification. In the diagram (a) representing deductive reasoning, both premises are asserted and the direction of entailment is in line with the direction of justification. The diagram (b) for inductive reasoning shows that the premises justify the conclusion, but the general conclusion (such as All ravens are black) entails the premises (e.g. The raven 1 is black, The raven 2 is black, etc.). Finally, the diagram (c) for reasoning by analogy shows that the asserted premises about the well known case(s) justify the conclusion, but the relation of entailment does not hold. Moreover, we may note that this method enables the representation of linked (diagrams (a) and (c)), convergent (not represented in the above diagrams) and divergent (diagram (b)) arguments. This project is in line with the proposal of treating the LWS tradition as a point of departure for modelling the linked-convergent distinction (see Selinger, 2014).

For the purpose of our paper it might be also interesting how Trzęsicki’s proposal could be compared to some basic notions which are used in argumentation theory in order to describe the diversity of argument structures. For example, the argument diagramming method proposed by Trzęsicki may be discussed in terms of four stages of a critical discussion within the pragma-dialectical model (e.g. van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 2004, pp. 59-62). Amongst four stages (confrontation stage, opening stage, argumentation stage, and concluding stage) at least two of them may be pointed out in the discussion of further areas of applying the diagramming method proposed by Trzęsicki, i.e. the confrontation and the argumentation stage. At the confrontation stage one may apply tools presented above to identify a difference of opinion by indicating in the diagram which propositions are asserted and which are rejected. At the argumentation stage one may indicate in the diagram which kind of inference has been performed, in order to apply proper criteria of argument evaluation.

Although the above discussion shows only some applications of the approach to classifying reasoning proposed by Łukasiewicz and continued by Czeżowski, it is worth noting that some ideas developed by Ajdukiewicz may also play an inspiring role for argument studies. As early as at the stage of formulating the general motivation for building his taxonomy of reasoning, his approach may be strikingly similar to the very rationale of contemporary argument studies which starts from analysing everyday communication practices. In his talk given at the 1st Conference of Logicians in 1952 in Warsaw which was later published in Polish in Studia Logica, vol. 2 (Ajdukiewicz 1955), Ajdukiewicz presented his critique of the taxonomy of types of reasoning proposed by Łukasiewicz and Czeżowski (Woleński, 1998, p. 44). One of Ajdukiewicz’s objections was that Łukasiewicz and Czeżowski defined some key terms employed in defining reasoning (such as ‘inference’) in a way which is far from their common use in natural language (Ajdukiewicz, 1955). Ajdukiewicz focuses in particular on a critique of definitions of terms which are involved by Łukasiewicz and Czeżowski in classifying reasoning. Amongst these terms there are: ‘reasoning’, ‘inference’, ‘proving’, ‘deduction’ and ‘reduction’. Since, according to Ajdukiewicz, definitions of these and other terms depart from concepts such as reasoning and inference present in everyday communication, some distinctions employed in classifying various kinds of reasoning (such as the distinction between reason and consequence) are artificial (Ajdukiewicz, 1955; see also Koszowy & Araszkiewicz, 2014, p. 287). This pragmatic approach will be further seen in Ajdukiewicz’s positive proposal of his own taxonomy of reasoning.

Since Ajdukiewicz developed and modified his attempts at classifying reasoning, some different proposals may be found in his works (Woleński, 1988, pp. 42-48). The latest proposal given in Pragmatic logic (Ajdukiewicz, 1974) seems to be particularly interesting for the purpose of this paper, because it may be treated as a clear manifesto of focusing not only on formal, but also on pragmatic aspects of reasoning. Within his taxonomy, Ajdukiewicz divides reasoning into two general categories:

(1) conclusive, and

(2) non-conclusive (Woleński, 1988, p. 47).

There are two forms of conclusive reasoning:

(i) subjectively certain and

(ii) subjectively uncertain.

Apart from details of this classification, let us only mention its key pragmatic features. Firstly, instead of using the notion of validity of reasoning, Ajdukiewicz introduces the concept of conclusiveness (Woleński, 1988, p. 47). Secondly, the notion of subjective uncertainty is clearly in line with those research strands in argumentation theory which stress the need of considering human fallibility in evaluating defeasible reasoning. Basing on these two features, we may point to the possibility of testing whether these ideas may be also applicable in the study of reasoning in argumentation theory, what might be the task for future inquiry.

4. Legal constructivism

The research conducted by the representatives of the Lvov-Warsaw School constitutes not only an important source of inspiration for the general studies on argumentation, but also for investigations concerning particular domains of argumentation, including legal argumentation. In particular, the legal-philosophical work of Sawa Frydman, one of very few lawyers among the LWS members, offers interesting insights into the controversy concerning reconstructive or constructive character of legal argumentation (hereafter: the Reconstruction / Construction Controversy, abbreviated to RCC).

The RCC may be formulated as follows (see Hage, 2013, pp. 125-126 for a broader introduction to the problem). Legal argumentation either performs only constructive function (the Constructivism Thesis, CT), or it is reconstructive in easy cases while constructive in hard cases (the Reconstructivism Thesis, RT). According to the CT, legal consequences of cases are always created by means of arguments, actually or possibly used to generate these consequences from some relevant premises. According to the RT, the CT is only locally true (it applies to the so-called hard cases), while in majority of cases (referred to as easy cases), the legal consequences of cases are already there, for they are the result of operation of legal rules, and they should simply be discovered, or reconstructed, by the law-applying organ.

It is not our purpose here to summarize the existing arguments supporting or attacking the RT or the CT (cf. Hage, 2013, pp. 142-143). Instead, it is our intention to show how Frydman’s (1936) work may provide an import to the merits of the on-going discussion. For the sake of self-contained character of this paper, we have to recall the basic features of Frydman’s theory of legal interpretation, briefly outlined in our past work (Koszowy & Araszkiewicz, 2014, pp. 294-295). However, the present elaboration will go deeper into the details of Frydman’s contribution.

Sawa Frydman is the author of one of the earliest consistent proposals (1936) of constructive account of statutory interpretation. The key technical term in this proposal is the ‘pattern of behaviour’ which is an abstract concept referring to certain possible states of affairs (Frydman, 1936, pp. 144-145). Patterns of behaviour may be encoded in different media, for instance in oral utterances (such as orders) and, more importantly, in statutory texts. Patterns of behaviour may be accounted for either directly (intuitively) or indirectly (by means of justification). The latter case of accounting for patterns of behaviour on the basis of statutory texts is referred to as interpretation (Frydman, 1936, p. 145).

Frydman’s general idea is to develop different ideal types of legal interpretation in the Weberian sense, which would be useful in empirical investigations. He rightly observes that it is difficult to indicate any ‘facts’ that would serve as truthmakers of the statements concerning assignment of meaning to statutory provisions. In consequence, the only part of legal statutory interpretation that may be analyzed from scientific point of view is the relation between its premises and its conclusion. In consequence, the process of legal interpretation is constructive, because it depends on the set of premises which is arbitrarily adopted by the interpreting person. Frydman defines the term ‘objective interpretation’ in the following manner: “statutory interpretation is objective if an only if it is true that from the premises p, q, r it follows that statute S contains the pattern of behaviour P” (Frydman, 1936, p. 177).

The basic argument used by Frydman to support his thesis concerning arbitrariness of premises used in the process of legal interpretation is the argument from plurality of theories of interpretation. In this connection, the author reviews several important theories of statutory interpretation discussed in the literature those days (Frydman, 1936, pp. 181-194). The presence of these discrepant theories, often leading to contradictory conclusions, is an indisputable fact and there are no decisive criteria that could lead to establishment of a preference relation between them.

The second argument is based on the observation of actual legal interpretive practice. Frydman rightly notes that the choice of interpretative arguments is dictated by practical needs and value judgments rather than by focus on ‘properness’ of a given set of adopted assumptions. In this connection it seems implausible to seek for a ‘right’ set of premises adopted in statutory interpretation. The question concerning ‘unique and objective’ sense of a statute is an ill-formed question (Frydman, 1936, pp. 196-197).

The arbitrary choice of premises that play justificatory role coexists with the fact that the very process of legal interpretation has well-defined structure and it encompasses the following elements (Frydman, 1936, pp. 208-209):

* the direction of interpretation – that is, taking a certain class of facts into account, that possibly lead to the establishment of the pattern of behaviour;

* the material of interpretation – all signs (in semantic sense of this term) that are investigated in the process of establishment of the abovementioned facts;

* the means of interpretation – the use of this or that material in the scope of a given direction of interpretation;

* the premise of interpretation – a statement, which defines a direction or means of interpretation, or the order of use and significance of each direction in the process of interpretation.

Interestingly, Frydman emphasizes the twofold role of logic in the process of statutory interpretation. If the premises are established in a precise manner, then inference of the conclusions is actually objective, because it is independent of the interpreting person. Hence, Frydman insists on establishing deductive relations between premises and conclusions in statutory interpretation. However, Frydman seems to accept also a broader account of logic, for he argues for application of logical tools in the process of comparison and reconciliation of results of different directions of interpretation. His brief informal account of this process invokes the concept of belief revision, which was introduced to the literature much later (Alchourrón, Gärdenfors & Makinson, 1985).

The theoretical framework presented above is a tool designed for empirical investigations concerning the phenomenon of statutory interpretation, and therefore it should not be treated as a descriptive model of this phenomenon. In particular, Frydman acknowledges that in reality some sets of premises used in the process of interpretation may be rooted so firmly in a given community of lawyers that the interpretative results generated by these premises may be seen as ‘true’ (Frydman, 1936, p. 239). However, the existence of such consensus is a purely empirical question: there is no necessity in assigning this and only this pattern of behaviour to a given statutory provision. In our opinion, Frydman’s account of statutory interpretation is an important predecessor of contemporary constructive accounts of legal reasoning. Due to its very precise formulation and deepened analyzes, the work of Frydman could still provide valuable inspiration for the present research on the subject and persuasive arguments supporting the CT; however, its the influence will remain limited in foreseeable future, because the referred work has been published in Polish only. Therefore, we see it purposeful to indicate the following aspects of Frydman’s work that can be particularly fruitful in the research on legal argumentation nowadays.

First, the conception of statutory interpretation discussed is one of the earliest legal-philosophical proposals which focuses on the notion of argumentation. Even if Frydman does not use the term ‘argument’ or ‘argumentation’, his analysis of the relation between premises and conclusions of interpretative reasoning may be almost effortlessly translated into the language of argumentation theory. Let us also emphasize that the general scheme of interpretative reasoning outlined above may serve as a general template for development of new argumentation frameworks for representation of statutory interpretation. In particular, the concept of ‘premise of interpretation’ is defined very broadly by Frydman, for it encompasses not only statements that support of demote different interpretative statements, but also statements concerning the sequence of use of different directions of interpretation, mutual relations between them etc. In this connection, Frydman’s conception may serve as a point of departure for development of a formal model of constructive argumentation dealing with statutory interpretation. One should note that such formal systems have been developed for the context of Case-Based Reasoning (CBR), characteristic for the systems of law in the US and in the UK (for instance: Bench-Capon & Sartor, 2003), but not for statutory interpretation, connected with continental European legal culture. In the context of statutory reasoning, Frydman’s broad notion of directions of interpretation enables a researcher to discuss and analyze a great variety of argumentation schemes that are actually used in statutory interpretation (for a general introduction to the topic of argumentation schemes see Walton, Reed & Macagno, 2008; for an initial application of this theory to legal interpretation see Macagno, Walton & Sartor, 2012; Araszkiewicz, 2013).

We are of the opinion that Frydman’s general framework may enrich and systematize the contemporary attempts to analyze statutory interpretation by means of different argument schemes. Note also that according to Frydman’s assumption of arbitrariness concerning choice of premises in interpretative reasoning, we obtain a negative result concerning the possibility of establishing a definitive preference relation between different methods of legal interpretation. However, this does not preclude defining local, or tentative, preference relations: the set of ‘premises of interpretation’ encompasses also statements concerning relative significance of directions of interpretation. This contention makes it plausible to state that the preference relations between conclusions stemming from different premises could play an important role in a model of statutory interpretation based on Frydman’s conception. Their determination would presumably take plays on the second logical layer of the process of interpretation, when different conclusions, presumably inconsistent, conclusions, are compared and revised.

Second, it is worth emphasizing that Frydman’s scientific project was developed to enable the sociologists to effectively investigate the actual statutory interpretation by means of empirical research. Interestingly, Frydman postulated conducting of statistical analysis of large-scale corpora of documents (Frydman, 1936, pp. 267-268), which should be assessed as a bold proposal in the 1930s, because there were no electronic repositories of legal documents those days. Nowadays, when these databases are easily available, the conceptual scheme developed by Frydman may be useful is designing research tools for analysis of the existing corpora and argumentation mining. In this connection we would like to point out that Frydman’s distinction between three ideal types of interpretation, that is, objective interpretation, apparently objective interpretation and anticipatory interpretation (Frydman 1936, p. 151) may be used as an efficient guideline for development of empirical research on legal argumentation. The criterion of the distinction is the attitude of the interpreting person. In case of objective interpretation, the interpreting person intends to construct the proper pattern of behaviour from the statute and relevant premises without earlier determination of the desired behaviour. In the apparently objective behaviour the person determines the desired pattern of behaviour first, and then seeks the justification of this pattern of behaviour in the statute. Finally, anticipatory interpretation aims at foreseeing interpretive behaviour of other parties (the opposing party to the dispute or the appellate judge). We are of the opinion that ignoring these distinctions in the process of empirical research on statutory interpretation may lead to certain distortions, for instance, to a false conclusion that certain method of interpretation is generally abused, where in fact it could be abused only in cases of apparently objective interpretation (used, for instance, in unjustified lawsuits etc.).

In summing up the above considerations, it should be stressed that the work of Frydman is exemplary as regards the logical culture of investigations in the field of law. Clarity of exposition of the scientific problems and careful conceptual distinctions together with explication of all elements of argument of the author form a good pattern of conducting of this type of conceptual analysis in the field of legal argumentation.

5. Conclusion

As the discussion of two example areas (i.e. argument representation and legal argumentation) of employing the LWS heritage in argument studies show, the logico-methodological ideas of the LWS constitute not only the roots of argument studies in Poland associated with the emerging Polish School of Argumentation (see Budzynska & Koszowy 2014, eds), but may also contribute to the current state of the art in argument analysis and representation. As we pointed out in this paper, amongst the ideas which may be paricularly inspiring for argument studies there are:

(i) Łukasiewicz’s theory of rejected propositions – as it might enrich the state of the art in argument diagramming, and

(ii) Frydman’s constructive account of statutory interpretation – as it may inspire current applications of argumentation schemes theory to interpretation of statutes and it could be useful for development of tools applied in empirical research on large corpora of legal documents (in particular, judicial opinions and doctrinal works).

These two detailed areas of inquiry may also constitute a motivation for exploring the broader context in which the main pillars of future systematic inquiry might be suggested. Amongst such pillars we may point to the following:

(i) classifications of reasoning as the foundation for developing argument diagramming methods; and in particular

(ii) the inclusion of the account of rejected propositions in argument diagrams;

(iii) the model of statutory legal interpretation based on the idea of construction;

(iv) the framework for future empirical research concerning the set of actually employed premises in legal reasoning.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Polish National Science Center for Koszowy under grant 2011/03/B/HS1/04559.

NOTE

i. Observe that although Łukasiewicz’s classification of reasoning was rather peripheral to his major research concerns, it turned out to be widely accepted in logic textbooks (Ajdukiewicz, 1955).

References

Alchourrón, C., Gärdenfors, P., & Makinson D. (1985). On the Logic of Theory Change: Partial Meet Contraction and Revision Functions. Journal of Symbolic Logic, 50, 510-530.

Araszkiewicz, M. (2013). Towards Systematic Research on Statutory Interpretation in AI and Law. In K. Ashley (Ed.), Legal Knowledge and Information Systems – JURIX 2013: The Twenty-Sixth Annual Conference, (pp. 15-24). Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications, Vol. 235. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Ajdukiewicz, K. (1955). Klasyfikacja rozumowań (Classification of reasoning). Studia Logica, 2, 278-299.

Ajdukiewicz, K. (1974). Pragmatic logic. Dordrecht/Boston/Warsaw: D. Reidel Publishing Company & PWN – Polish Scientific Publishers. (English translation of Logika pragmatyczna. Translated by O. Wojtasiewicz. Original work published in 1965).

Bench-Capon, T.J.M., & Sartor, G. (2003). A model of legal reasoning with cases incorporating theories and values. Artificial Intelligence, 150, 97-142.

Bocheński, J.M. (1994). Sto zabobonów (One hundred superstitions). Kraków: Philed.

Budzynska, K., & Koszowy, M. (2014, Eds.). The Polish School of Argumentation. The special issue of the journal Argumentation, 28(3).

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of argumentation. The pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frydman, S. (1936). Dogmatyka prawa w świetle socjologii. Studjum I: O wykładni ustaw (Legal dogmatics in the light of sociology. Study 1: On interpretation of statutes). In B. Wróblewski (Ed.), Ogólna nauka o prawie (General jurisprudence) (pp. 141–316). Wilno: Nakładem Koła Filozoficznego Studentów Uniwersytetu Stefana Batorego w Wilnie (Issued by the Scientific Circle of the Students of Stefan Batory University in Vilnius).

Hage, J. (2013). Construction or reconstruction? On the function of argumentation in the law. In C. Dahlman, & E. Feteris (Eds.), Legal argumentation theory: Cross-disciplinary perspectives (pp. 125-143). Law and Philosophy Library, vol. 102. Dordrecht: Springer.

Jadacki, J.J. (2009). Polish analytical philosophy. Studies on its heritage. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Semper.

Koszowy, M. (2010). Pragmatic logic and the study of argumentation. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric, 22 (35), 29-45.

Koszowy, M. (2013). Polish logical studies from an informal logic perspective. In D. Mohammed & M. Lewiński (Eds.), Virtues of argumentation. Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of the Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation (OSSA), 22-26 May 2013 (pp. 1-10). Windsor, ON: OSSA.

Koszowy, M., & Araszkiewicz, M. (2014). The Lvov-Warsaw School as a source of inspiration for argumentation theory. Argumentation, 28, 283-300. DOI 10.1007/s10503-014-9321-7

Lapointe, S., Woleński, J., Marion, M., & Miskiewicz, W. (2009, Eds.). The golden age of Polish philosophy. Kazimierz Twardowski’s philosophical legacy. Dordrecht: Springer.

Łukasiewicz, J. (1921). Logika dwuwartościowa, Przegląd filozoficzny 23 (1921), 189–205. English translation: Two-valued logic, in J. Łukasiewicz, Selected Works, ed. by L. Borkowski (pp. 89–109). Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1970.

Macagno F., Sartor G. & Walton D. (2012). In M. Araszkiewicz, M. Myška, T. Smejkalova, J. Šavelka, & M. Škop, (Eds.) ARGUMENTATION 2012 – the 2nd International Conference on Alternative Methods of Argumentation in Law, (pp. 63-75). Brno: Masarykova Univ.

Selinger, M. (2014). Towards Formal Representation and Evaluation of Arguments. Argumentation, 28, 379-393. DOI: 10.1007/s10503-014-9325-3.

Simons, P. (2002). A golden age in science and letters: The Lwów-Warsaw Philosophical School, 1895–1939. Retrieved July 15, 2014, from https://sites.google.com/site/petermsimons/peter-s-files.

Słupecki, J., Bryll, G., & Wybraniec-Skardowska, U. (1971). Theory of rejected propositions, I. Studia Logica, 29, 75–123.

Słupecki, J., Bryll, G., & Wybraniec-Skardowska, U. (1972). Theory of rejected propositions, II. Studia Logica, 30, 97–145.

Smith, B. (2006). Why Polish philosophy does not exist. In J. J. Jadacki & J. Paśniczek (Eds.), The Lvov-Warsaw School: The New Generation (pp. 19–39). Poznań Studies in the Philosophy of the Sciences and the Humanities, vol. 89. Dordrecht/Boston/Lancaster: Kluwer.

Tarski, A. (1995). Introduction to Logic and to the Methodology of Deductive Sciences. New York: Dover Publications.

Trzęsicki, K. (2011). Arguments and their classification. Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric, 23(36), 59-67.

Walton, D., Reed, C., & Macagno, F. (2008). Argumentation schemes. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Woleński, J. (1988). Klasyfikacje rozumowań (Classifcations of reasoning). Edukacja Filozoficzna (Philosophical Education), 5, 23–51.

Woleński, J. (1989). Logic and philosophy in the Lvov–Warsaw School, Dordrecht/Boston/Lancaster: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Woleński, J. (2013). Lvov–Warsaw School. In E. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved July 15, 2014, from http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/lvov-warsaw/

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply