Joseph Semah ~ After Paul Celan, Tango and Fugue

Comments Off on Joseph Semah ~ After Paul Celan, Tango and Fugue Being a Dutch art historian, working in Germany, I was asked to give a short introduction in English to an Israeli artist working in the Netherlands. The inherent confusion, the mingling of languages, that follows from this is a good starting point to talk about the work of Joseph Semah.

Being a Dutch art historian, working in Germany, I was asked to give a short introduction in English to an Israeli artist working in the Netherlands. The inherent confusion, the mingling of languages, that follows from this is a good starting point to talk about the work of Joseph Semah.

Because there is even another language we will have to talk about: Semahs language of images.

Does art have a mother tongue? Who understands the language of art? Or more specific: who understands Joseph Semahs art?

Semah is often said to be a difficult unintelligible artist – which is, let me state this right at the beginning, not true. And Semah being presented as an Israeli artist who explores both European and Jewish thought and the interplay between these two, most spectators may feel as if they miss something. But what is missing might be the point. You cannot expect a spectator to know both the European and Jewish tradition and the main mistake when dealing with Semahs work seems to me, this urge to start from such knowledge instead of plain curiousness. So the strategy I suggest to you is plain curiousness: you will discover things you did not know.

Baruch de Spinoza

This exhibition focuses on Paul Celan, not just because the Goethe Institut organizes a festival focused on this poet, but because Celan stands at the beginning of Semahs work as an artist.

In the late 1970s both Baruch de Spinoza and Paul Celan were starting points for Joseph Semah as an artist. Spinoza, the Amsterdam philosopher with Sephardic roots who published in Latin and Celan the Rumanian poet who wrote in German.

In both cases there is an important difference between their mother tongue (Hebrew) and the language by which they entered the public arena.

It is easy to see the similarity. Semah himself comes from a Hebrew speaking background and uses another language to attract attention. This other language is art. First of all this similarity suggests that art is as alien to Semah as German to Paul Celan. Art – and this is a very provocative point Joseph Semah makes – is a western language. But secondly it suggests that this language can be learned, used and especially

Celan proves that such a language can gain enormous depth. So, obviously right from the beginning Semahs work is not without ambition.

Identity as a question

Semahs theme is identity. Not identity in a simple nationalist manner, but identity as a question. What is identity? What is my identity? In a series of provocative art works Joseph Semah used famous forms and visual codes from modern art.

Think of big iron cubes. So every European art lover would conclude “minimalism”, but Semah gave a subversive twist to this: these work look like modernism, but there is something strange in them. Their positioning reflects the form of a synagogue or their number (22) the Hebrew alphabet.

Joseph Semah opposes the esthetic approach of modernism. To him every form has a meaning. For example: The simple T-Form he presents in a lot of his works (here in the installation with the glasses) is not only a beautiful form but to him it also bears the symbolism of the Temple. What does that mean? Contemporary art is a system and the system is based on signs and people who know these signs. And Semah reminds us that the signs may mean much more. What for you may ask? If the signs mean more, art is not about specialists knowing what art is, but on a much more fundamental level, art is about communicating with the other.

Inclusion, exclusion

This is a philosophical problem, and let me try to explain it within the limits of a short talk. On a sociological level art is about inclusion and exclusion. People who know art belong to the club. Why something is art is not discussed as it functions as a medium of inclusion. And outsiders are not invited. Enter Joseph Semah. This artist presents his Jewish heritage as a way to look at modern art. By this he poses the first question: why is something art? Next he poses the second question: Why does the Jewish heritage play no role in contemporary art? According to Joseph Semah Jewish heritage plays at least some role in art, but think of the truly democratic meaning of his approach. You do not know art, but if you study and look close you may understand more and more of it. True: This is a simple mechanism and Semah is not afraid to use it.

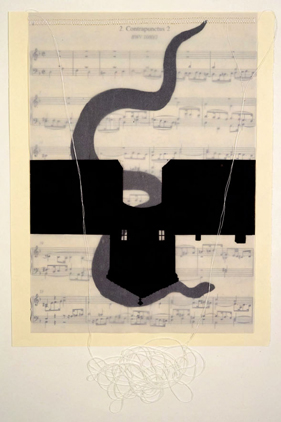

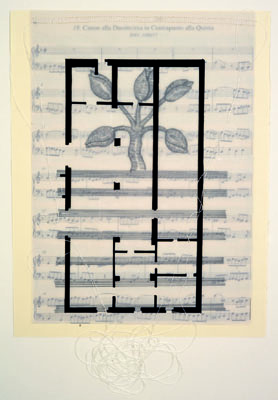

In the center of this exhibition you will find a new series of paper works relating to Paul Celans famous “Todesfuge”, one of the most important poems in German language of the 20th century. Celans poem is famous because it is beautiful and this of course is a problem as it deals with the holocaust. You all know Adornos famous dictum concerning the limits of representation: After Auschwitz it is barbaric to write poetry. And Celans poem is a superb answer to this.

Joseph Semah presents us with beautiful images. But these images on tracing paper relate to Auschwitz. And in their background you will find music sheets from Johann Sebastian Bach. The artists binds these images. Literally. He binds them by white thread and thus not only presents the viewer with layered images, but the layering itself becomes an important part of the work. So the message is: What happened in Auschwitz happened with Bach in the background.

Todestango

Originally Celans poem was entitled Todestango, referring to the tango that was played during executions. But Celan changed Tango into Fugue. And by this the math and geometry of Bachs famous composition became a symbol for the industrial killing of the Jews. So Semahs work poses the famous question, whether Bach, Beethoven or other famous representatives of German culture are responsible for the holocaust, and while the answer is of course “no”, this “no” is complex. Just by posing the question, one provokes irritation. And it is this irritation that the answer lies in. Because to put it bluntly: There is nothing in Bach to prevent mass murder.

So in this work Joseph Semah confronts viewers with beauty and terror in one multilayered image. And while most contemporary imagery tends to focus on emotion, Semah tries to reach emotion via intellect. And this is much more disturbing. His layering is even more complex as he also incorporates elements from his own earlier works. And by this he relates his own work to Bach, Celan and the holocaust. Which brings me to an interpretation of the title of this work and of the exhibition.

GaV Le-GaV

“After Paul Celan, Tango and Fugue; This, however, brings us GaV Le-GaV (Back to Back) with the artist’s promise”. The first part is easy. But then comes the second part about the artists promise. What is the artists promise? It is the artwork. Every artwork carries the promise of the artist. Not just Semahs. In our society we believe that a piece of art gives us insight into the inner life of an artist. And by this modern art a constant circle of frustration is being created, as a spectator will never come closer through the work.

Semah now introduces a strange but intriguing topic: the back to back (Gav le Gav). The idea is utterly complex and I have explored it elsewhere, but there is a simple core. Whenever you and I are standing back to back, there has to be trust. So Semahs title is relating to frustration and trust. In my opinion – but this is a very personal view – trust is a good starting point. Semahs work is posing difficult and painful questions, but he is not out to hurt you. He presents his thinking through his art, and by following this you will not get to know him, but you’ll be surprised by what you’ll find.

This brings me back to Paul Celan. In a famous letter, he related poetry to trust. And from this he came to his main topic, not the holocaust, nor his Jewish heritage or the German language, but truth: Truth in a philosophical sense. Celan is the postwar poet struggling with truth, knowing that what surrounds modern man, are facts. But that truth is something utterly different.

Todesfuge

And this may be one of the lessons to be learned from Paul Celan. Whether talking in Germany, Israel or the Netherlands, we constantly feel the limits of representation vice versa the trauma of the twentieth century. Confronted with the killing of six million European Jews, we can observe two prevailing strategies in our society. One of them focuses on single biographies, the other on the numbers. And it does make a difference to be talking about one human being or about 6 million dead Jews. But neither the first nor the second strategy comes close to truth. Paul Celan was one of the artists who understood that art can do this. His Todesfuge tells neither about one single person, nor about the masses nor does it name the murderers. But there is truth in it.

By creating this series Joseph Semah not only gives an interpretation of Paul Celan but also shows his adherence and admiration. This is very rare in contemporary art.

—–

About Arie Hartog

Dr. Arie Hartog is the director of the Gerhard-Marcks Museum (Bremen, Germany) since October 2009.

The Dutch born Arie Hartog is a specialist for figurative sculpturing. He was born in 1963 in Maastricht. He studied art history at the catholic university Nijmegen (KUN), where he got his doctorate in 1989 on the topic of modern German figurative sculpturing. His mentor Prof. Dr. Christian Tümpel drew his attention to the sculptor Gerhard Marcks in 1984. He then became a student of Marcks and later an independent employee who was trusted with the reorganisation of the extensive Bremen drawings collection. Between 1992 and 1995 he worked as a “Junior Docent” for history of architecture and museology at the KUN, until he became Kustos in Bremen in 1996. Being a specialist for sculpturing, he showed some expertise with the intercultural exchange of art in cooperation with the Bremen and Niedersachsen church.

At the Gerhard-Marcks house he established his reputation as a curator of exhibitions with the topic sculpturing in the 20th century. He has been publishing on the topic of art of the 20th and 21st century and also published several scientific texts for example a catalogue raisonné of Rainer Fetting and Waldemar Otto. Hartog showed a special interest for artists who have been working outside general trends and who developed their own picture language like Karl Appel, Reg Butler, Rainer Fetting, Bruno Gironcoli, Waldemar Grzimek, David Nash, Joseph Semah und Shinkichi Tajiri.

Hartog played an important role in a team, which developed diversified sculpturing exhibition programs, which are different from the usual monographic oriented museums. He initiated a scientific exchange between research facilities and museums abroad, which established the international reputation of the museum.

www.marcks.de

About Joseph Semah

Joseph Semah (1948) was born in Baghdad, Iraq, in 1948. From 1950 he grew up in Tel Aviv, Israel. After finishing gymnasium, Semah studied Electronics and Philosophy at the University of Tel Aviv. At the same time he was developing as an artist.

In the mid 1970s Semah made the decision to leave Israel. He refers to this as self-imposed exile. From then on he was a ‘guest’ of London, Berlin and Paris. Since 1982 Semah resides in Amsterdam, where he founded the Makkom Foundation, which in the 1980s organized projects based on interdisciplinary research in the arts.

Joseph Semah’s oeuvre of inextricably connected images and text evidences an impressive search for the meaning of human existence: The relations between man and fellow-man, between the self and the other. An attempt to contribute to mutual understanding and tolerance, combined in his research with insights drawn from religion, science and art.

www.josephsemah.nl

You May Also Like

Comments