ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Why Study The Overlap Between “Ought” And “Is” Anyways? On Empirically Investigating The Conventional Validity Of The Pragma-Dialectical Discussion Rules

No comments yet 1. Introduction

1. Introduction

This paper forwards the (presumably controversial) thesis that the use-value of empirically studying the conventional validity of the pragma-dialectical discussion rules (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 2004: 190-196) is heuristic. This thesis seems natural (to me), if the consequences of a particular theoretical commitment are appreciated: When treating argumentation that supports a descriptive standpoint with a normative premise (aka. a “value sentence”), and vice versa, pragma-dialecticians incur a commitment on the transition between “ought” and “is.” This commitment amounts to embracing the “naturalistic fallacy” as a discussion move that is never appropriate.

In Section 2.1, the aim, method and main result of the recent empirical investigation of van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels (2009) are presented. In Section 2.2, the discussion rules’ conventional validity is discussed. Vis à vis the explanation offered by the study’s authors – or so I admit –, the theory-internal purpose of this study remains rather unclear to me. After all, as stressed by the authors, the normative content of the pragma-dialectical theory is neither open to refutation by empirical data, nor to confirmation by such data (Section 3). Therefore, I claim, the theoretical value of this investigation is heuristic (Section 4). Section 5 comments on a tension between the level of measurement and the level at which measurement is reported.

2. Treating Conventional Validity Empirically

2.1 Aim, Method and Main Result

The aim is to determine “if and to what extent the norms that ordinary language users (may be assumed to) apply in judging argumentative discussion moves correspond to rules which are part of the ideal model of critical discussion” (van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels 2009: v; italics added). This means to study the rules’ intersubjective validity or – insofar as conventions are understood to normally remain implicit – their conventional validity (see van Eemeren and Grootendorst 2004: 56, fn. 35). In contrast, the rules’ problem validity cannot be studied empirically, but is a matter of expert agreement.

Four of the ten pragma-dialectical discussion rules are selected: Freedom Rule, Obligation to Defend Rule, Argumentation Scheme Rule, Concluding Rule. Based upon these rules, mini dialogues (of two to four turns) are created. On expert opinion, the last turn of these either is or is not a clearly fallacious discussion move (“multiple message design”). Under variation of domains/contexts (domestic, political, scientific), dialogues are presented to lay arguers – mostly younger students – in questionnaire form. This occurs under the normal precautions with empirical research (e.g., including filler items, in random order, controlling loadedness/politeness of examples, retesting items from previous studies); a sample size of 50 is typical. Refer to van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels (2009: 64f.) for examples. Hample (2010) and Zenker (2010) report further details; an accessible summary is Hornikx (2010). Notably:

“The third domain [the scientific discussion] was described as the scientific discussion in which – as was emphasized – it was not so much a matter of persuading others but of resolving a difference of opinion in an acceptable manner: Who is right is more important than with whom one agrees.” (van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels 2009: 66).

Participants were then asked to rate the reasonableness of the last move in a dialogue on a seven point Likert scale (1-7). Thus, for each dialogue and each subject, a reasonableness judgment value (RJV) becomes available. These RJVs are averaged – yielding an averaged reasonableness value (ARV) – , then assessed on measures of statistical significance (yielding, e.g., correlation coefficient, standard deviation, effect size).

This operationalizes reasonableness as a seven degree notion. One can now quantify the extent to which ordinary arguers’ responses are (in)consistent with the normative content of the four discussion rules as applied to some (mini-)dialogue. The value four (4) being the middle point, one reasons: If this rule, the violation of which generates these discourse fragments, is conventionally valid (to some extent), then fallacious fragments receive an ARV < 4 and non-fallacious fragments receive an ARV > 4. One compares whether the RJVs do, on average, fall within the expert predicted region.

Applied to four of ten rules, with the exception of the confrontation and the opening stages (van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels 2009: 224), the investigation is non-exhaustive in the following sense: In principle, violations of different rules (or of a subset of the same rules, but in a different discussion stage) might lead to different results. The ten rule version is a popularization of the more technical 15 rule set (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 2004: 135-157; Zenker 2007). How the 15 and the 10 rule set are related is not clear in detail. So, “four out of ten” or “x out of 15” rules have been studied. For a list of fallacies used, see van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels (2009: 223).

Under these reservations, the main result is that

“[T]he body of data collected indicate that the norms that ordinary arguers use when judging the reasonableness of discussion contributions correspond to a rather large degree with the pragma-dialectical norms for critical discussion.” (van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels 2009: 224)

This claim is based on the size of the effect obtained in comparing the ARVs for fallacious and non-fallacious discourse fragments.

2.2 Conventional Validity

Throughout the development of the pragma-dialectical research program, it has been contended that “[t]he [pragma-dialectical] rules (…) are problem valid because instrumental in the resolution process by creating the possibility to resolve differences of opinion” (van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels 2009: 27). They are considered instrumental to resolving a difference of opinion insofar as a violation of any rule is understood as a hindrance to this aim.

A further contention is normative in character: The pragma-dialectical rules should be conventionally valid, i.e., agreeable to lay arguers. This means, the rules’ content should not conflict with the norms that lay persons (i.e., those not specifically trained in the pragma-dialectical theory) can be construed to accept. This norm is regularly traced to Barth & Krabbe (1982: 21-22) or Crawshay Williams (1957).

Should these two books answer the question why it is important that the pragma-dialectical rules are conventionally valid, then this answer is hidden well. At any rate, neither van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels (2009) nor the comprehensive van Eemeren & Grootendorst (2004) offer much of an explanation. At the relevant places (known to me), it is stated that the rules should be conventionally valid, not why (e.g., van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels 2009: 27).

Perhaps an exception is a more detailed explanation in a 1988 article. From this, three quotes follow. These suggest that the conventional validity of discussion rules – understood as the acceptability or the acceptedness of some normative content by lay arguers – arises with insight into the rule’s pragmatic rationale. That is, the quotes are not inconsistent with an interpretation according to which intersubjective acceptance comes about through insight into problem validity.

“We believe that the process [of solving problems with regard to the acceptability of standpoints] derives its reasonableness from a two-part criterion: problem-solving validity and conventional validity (cf. Barth and Krabbe 1982: 21-22). This means that the discussion and argumentation rules which together form the procedure put forward in a dialectical argumentation theory should on the one hand be checked for their adequacy regarding the resolution of disputes, and on the other for their intersubjective acceptability for the discussants. With regard to argumentation this means that soundness should be measured against the degree to which the argumentation can contribute towards the resolution of the dispute [i.e., the degree of problem validity], as well as against the degree to which it is acceptable to the discussants who wish to resolve the dispute [i.e., the degree of conventional validity].” (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1988: 280)

Pace stylistic changes (e.g., ‘dispute’ has been replaced by ‘difference of opinion’), this is in line with the 2004 presentation. Further in the same article:

“It may now be possible to make plausible that the rules are such that they merit a certain degree of intersubjective acceptability, which would also lend them some claim to conventional validity. [paragraph] The claim of acceptability which we attribute to these rules is not based in any way on metaphysical necessity, but on their suitability to do the job for which they are intended: the resolution of disputes [i.e., their problem validity]. The rules do not derive their acceptability from some external source of personal authority or sacrosanct origin. Their acceptability [i.e., their conventional validity] should rest on their effectiveness when applied [i.e., their problem validity]. Because the rules were developed exactly for the purpose of resolving disputes, they should in principle be optimally acceptable to those whose first and foremost aim is to resolve a dispute. This means that the rationale for accepting these dialectical rules as conventionally valid is, philosophically speaking, pragmatic.” (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1988: 285; italics added)

Particularly the last sentence suggests (to me) that understanding the rationale of the pragma-dialectical rules brings about their acceptance. This interpretation seems to be consistent with that provided in van Eemeren and Grootendorst (2004: 187). That the rationale is pragmatic, I take to be irrelevant for providing some rationale for acceptance. It seems moreover uncontroversial (to me) that understanding the rationale for accepting them as conventionally valid presupposes understanding (learning) the pragma-dialectical rules. Similarly:

“The speech acts which are most useful to all concerned who share a certain goal, for example to resolve a dispute, possess a form of problem validity which may lead to their claim of conventional, intersubjective validity.” (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1988: 289, n. 14)

Vis à vis these (less recent) quotes, and absent a more recent detailed explanation, it remains unclear (to me) why the pragma-dialectical rules should be conventionally valid independently of having being learned. One’s methodology may very well support the claim that they are (or not), but why begin?

If they are problem-valid (i.e., acceptable as a solution to a problem), then recognizing their problem-validity expectably brings about their acceptedness, and brings it about for this reason (cf. van Eemeren and Grootendorst 2004: 187). At any rate, the rules’ problem validity and one’s (cognitive) ability to appreciate their pragmatic rationale – are sufficient for acceptance (thus, for conventional validity). If so, how can being acceptable/accepted by those not trained in these rules be important for the theory?

It is trivial to state that the pragma-dialectical (or some other set of problem valid) rules cannot be effective in leading to dispute resolutions, unless at least two disputing parties de facto accept them (explicitly or implicitly). In one scenario, the pragma-dialectical rules being conventionally invalid means that problem valid rules are unaccepted by lay arguers (if the rules are problem valid). So, ceteris paribus, lay persons might not be expected to maintain a discussion (and obtain a result) which squares with the rules. Resolutions of differences of opinion would then perhaps be less expectable?

This author fails to see the upshot. Why demand (“should”) conventional validity independently of rule acquaintance?

I discount an otherwise important comment by Lotte van Poppel (personal communication). She points out that it might be less probable for the social aim behind the pragma-dialectical research program (improving argumentative praxis) to be reached, if the theory’s normative content turned out to be not accepted by lay arguers. This cannot merely relate to the exact formulation of said content; it must be more than a matter of style. If style did matter, why investigate conventional validity in an indirect way, rather than display the rule set and ask for assent? On this indirectness, see van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels (2009: 49f.).

Insofar as the comment then concerns the content, rather than various ways of formulating it (e.g., by avoiding/using technical terms): If lay arguers and expert judgment do not converge on the content of (a set of) problem valid rules – perhaps so be it! It remains unclear (to me) why one assesses (on a methodologically hardened measure) the distance between expert and a lay person judgment. Granted experts find the normative content problem-valid, what support does the content receive from convergence with lay arguer judgment? What doubt arises from divergence?

At this point, it does not help to learn that empirical data take on a special role. As the next section shows, distance between expert and lay person judgment appears to be of no immediate theoretical relevance.

3. The Special Status of the Results

3.1 Compare, not Test

Compared to applying and testing an empirical theory, the data obtained are special: “Empirical data can neither be used as a ‘means for falsification’ nor as ‘proof’ of the problem validity of the discussion rules” (van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels 2009: 27). Standardly, an empirical theory is tested against experience by applying it to a phenomenon (for which the theory is expected to account), in order to derive a prediction. In this case, the prediction is a judgment on the (non-)fallaciousness of some discourse item.

With A for antecedent, T for theory and P for prediction, applying an empirical theory may take the deductively valid form: A; T; (A & T) -> P; ergo P (modus ponens). If the prediction, P, is born out – and A is not in doubt (!) –, then T counts as confirmed. Note, however that, on a deductive construal, such confirmation would instantiate a deductively invalid schema (affirming the consequent).

If the prediction is not born out (i.e., non P is true), and A is not in doubt, then – again, on a deductive construal – falsification instantiates a valid form (modus tollens). In deductive logic, however, only the negation of (A & T) follows from non P; to derive non T, A must be less retractable than T (see Lakatos 1978; Zenker 2009).

In contrast, the normative content of the pragma-dialectical theory is not tested against lay person judgments, but compared to them (van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels 2009: 27). This means, some discourse fragment, A, under application of the pragma-dialectical theory, T, may very well deductively imply a prediction, P: “This fragment is (not) fallacious.” That much is captured by ‘(A & T) -> P’. However, P and the lay person judgment con- or diverging does not (deductively logically) affect the theory.

The explanation offered in defense of this odd support behavior – vis à vis empirical theories, Lakatos might speak of “immunization” – builds on the contention that the pragma-dialectical theory offers norms rather than descriptions.

3.2 Normative vs. Descriptive Contents

The standpoint in van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels (2009) is: What lay persons do or do not accept can neither be turned against the theory in the sense of falsification, nor support the theory in the sense of verification. (Recall from above that falsification can be treated in deductive logic; verification requires a notion of inductive validity.) The explanation for this standpoint is comparatively brief.

“The presumption in all our empirical studies is that the discussion rules involved are problem valid; the focus is on their conventional validity. The status of the results of this empirical work is special: The empirical data can neither be used as ‘means of falsification’ nor as ‘proof’ of the problem validity of the pragma-dialectical discussion rules. In the event that the empirical studies indicate that ordinary language users subscribe to the discussion rules, it cannot be deduced that the rules are therefore instrumental. The reverse is also true: If the respondents in our studies prove to apply norms that diverge from the pragma-dialectical discussion rules, it cannot be deduced that the theory is wrong. Anyone who refuses to recognize this is guilty of committing the naturalistic fallacy, the fallacy that occurs when one inductively jumps from “is” to “ought.” (van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels 2009: 27)

On might take this quote to express a meta level assertions about the inferential relation between a set of normative and descriptive statements. In effect, the standpoint is: There is no deductive inferential relation. This standpoint also shows at object level when evaluating discourse items in which a descriptive standpoint is supported by value statements (normative premises).

“The combination of a descriptive standpoint and a normative argument always leads to an inapplicable argument scheme: The acceptability of a descriptive standpoint is after all independent of the values that are attached to the consequences of the acceptance of that outcome” (van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels 2009: 172).

Put more generally, “(…) whether something is true or not in a material sense does not depend on the question if we like it or not” (van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels 2009: 172). So, truths (“facts”) do not receive support from, nor can they be undermined by human (dis-)approval.

Pragma-dialectics, of course, is a normative theory. The discussion rules are claimed to be supported by achieving the theoretical value of problem validity. This value is achieved through systematically identifying hindrances to a resolution oriented discourse (aka. fallacies). Clearly, to claim problem validity of a normative theory is not to assert a norm, but a fact – if it is one. So, lay arguers endorsing norms (in)compatible with the pragma-dialectical ones does not (without committing a naturalistic fallacy) license a claim about the theory’s problem validity: Just as undermining norms by facts is considered fallacious, supporting facts with norms is considered fallacious.

These contentions indicate that the naturalistic fallacy is a theoretical commitment for pragma-dialecticians. This may surprise. After all, it has been recognized that “fallaciousness” depends on various conditions, to the point that “fallacies can have sound instances” is a meaningful assertion in some contexts. Pragma-dialecticians appear committed that this is not so in the cases discussed here.

3.3 The Theoretical Value of Inconsistency

To summarize the above: Facts (here: the reasonableness judgments of ordinary speakers) are impotent with respect to norms (here: the pragma-dialectical rules). On this background, why is the conventional validity of the pragma-dialectical rules under study to begin with? After all, in case the rules would be conventionally valid – and the claim is that they are to a rather large extent – this at most supports conditional claims, such as: If ordinary speakers accept normative contents, then these contents are not inconsistent with the normative content of the pragma-dialectical theory.

“Just as would be the case in corpus research, in our series of experiments the conventional validity of the pragma-dialectical rules is investigated not in a direct, but in an indirect sense. Due to the fact that discussion fragments that contain a fallacy are found to be unreasonable by normal judges, and fragments that do not contain any fallacies are deemed reasonable, we deduce that in the judgment of the fairness of argumentation the respondents concerned appeal, whether implicitly or explicitly, to norms that are compatible, or at least not contradictory, to rules formulated in the pragma-dialectical argumentation theory”. (van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels 2009: 49, italics added)

This indirectness comes about for the (above discussed) reason that, by the authors’ standards, a normative theory cannot be falsified by descriptive data, nor can its problem validity be confirmed by such data. Hence, consistency between the theory’s normative content and the content which speakers may be construed to rely on is rather useless for the theory. On the other hand, inconsistency between the theory and a lay-person judgment has no bearing on the theory either, but has heuristic value. Inconsistency informs on “what works” without specific training and what does not.

4. Heuristics

“Anomalies” forthcoming in this study should prove relevant for theoretical development. Most important, perhaps, context not only matters but counts. For example, participants judge an ad hominem fallacy to be as reasonable in a domestic as in a political context, but less reasonable than in a scientific context. Similarly, a direct personal attack in a scientific context is judged to be less reasonable than a tu quoque in the same context (ARV = 2.57; standard deviation 0.81 vis à vis 3.66; 0.86).

Normatively, that the reasonableness value should be similar or the same in all three contexts, and for both variants of the ad hominem in the same context, is a defensible claim. Note that nothing in the standard theory explains such a context-dependency.

When a standpoint enjoying presumptive status is supported in a fallacious manner, then participants tend to judge this move more leniently than when no such presumption is enjoyed. Normatively, this may not sit well with everybody. Moreover, there are (perhaps striking) differences in culture: some robust effects “break down.”

Without training, lay persons will normally not be able to reliably distinguish between a sound ad absurdum and a fallacious ad consequentiam argument. On the other hand, participants do reliably distinguish the legal principle according to which a presumption of innocence holds unless proven otherwise, suggesting that further legal principles may generate robust effects as well.

The “trickiness” of the mini dialogues may be varied in future work, to investigate the point at which variation in content produces effects. Discourse fragments in this study are conspicuously simple. Some “tweaking” towards realistic content should see rules “breaking down.” After all, also this study supports the claim that participants tend to be influenced by the content of a standpoint: If you assent to what is supported by fallacious means, you will judge such fallacies more leniently than you would, if you did not assent. Though perhaps understandable, even demonstrating such effects to depend on context would still register as unacceptable in some normative framework.

5. Data Reporting

A last point pertains to the tension between the level of measurement and the level of reporting measurements. As mentioned above, measurement occurs on a seven point scale: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 (Likert 1932); very (un)reasonable marks the ends. Without further assumptions, this means that reasonableness judgments values are recorded at ordinal level. Here, one lacks distance information. It counts as unknown if the distance between 5 and 6, say, is the same as that between 2 and 3.

When reporting and statistically treating data, the assumption is that the distances are the same. This is needed. Otherwise, averaging – which yields fractions (e.g., an averaged reasonableness value of: 2:200/375 would be meaningless. Thus, data are treated as if they had been obtained at interval level. Deeply entrenched, the equi-distance assumption can be doubted in a particular case. The topic should make for a good case study on a scientific controversy. See Jamieson (2004), Carifo & Perla (2007) and Norman (2010) for both positions.

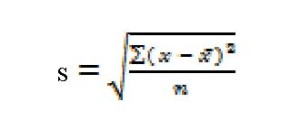

The standard report formats are the mean plus standard deviation. The mean is the sum of all measurement-values divided by the number of measurements. To indicate the spread of data points provided the mean, the standard deviation, s, is used (where x is a data value, x bar the mean, and n the number of measurements) (Figure 1).

The standard deviation is a widely accepted measure of dispersion. Yet, the value of s will not allow reconstructing the exact spread. Readers remain ignorant as to how many subjects showed what deviation in their reasonableness judgments. This makes data less useful for replication. By exactly how much individuals differed is hidden, since ARJs have replaced RJVs (see Section 2.1).

It suggests that the aim of the study was not to report the precise reasonable values assigned to artificial discourse items. Rather, the point was to show that, for the mini dialogues constructed (which suffer purposefully from near-triviality), theoretical prediction and averaged lay person judgment converge. Results strongly suggest that it is possible to construct examples which lay persons distinguish – on average and to a rather large extent – into fallacious and non-fallacious moves.

6. Conclusion

The theoretical purpose of comparing expert and lay person judgments concerning the reasonableness of rule-generated discourse fragments remains to be explicated. In the absence thereof, the naturalistic fallacy may count as a theoretical commitment for pragma-dialecticians. Whether this commitment needs additional justification would seem to depend on prior theoretical commitments.

Several examples of the heuristic value of the empirical investigation of the conventional validity of four of ten pragma-dialectical discussion rules were pointed out. On pains of having appeared critical, readers are reminded of two reviews (Hample 2010, Zenker 2010) praising van Eemeren, Garssen and Meuffels (2009). The study is highly relevant, irrespective of one’s theoretical background.

REFERENCES

Barth, E.M., & Krabbe, E.C.W. (1982). From Axiom to Dialogue: A Philosophical Study of Logics and Argumentation. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Carifo, J., & Perla, R.J. (2007). Ten Common Misunderstandings, Misconceptions, Persistent Myths and Urban Legends about Likert Scales and Likert Response Formats and their Antidotes. Journal of Social Sciences, 3, 106-116.

Crawshay-Williams, R. (1957). Methods and Criteria of Reasoning: An Inquiry into the Structure of Controversy. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (1988). Rationale for a Pragma-Dialectical Perspective. Argumentation, 2, 271-291.

Eemeren, F.H. van, & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A Systematic Theory of Argumentation. The Pragma-dialectical approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eemeren, F.H. van, Garssen, B., & Meuffels, B. (2009). Fallacies and Judgments of Reasonableness. Empirical Research Concerning the Pragma-Dialectical Discussion Rules (Springer Argumentation Library, Vol. 16). Dordrecht: Springer.

Hample, D. (2010). Review of Eemeren, F.H. van, Garssen, B., & Meuffels, B. (2009). Argumentation, 24, 375-381.

Hornikx, J. (2010). Review of Eemeren, F.H. van, Garssen, B., & Meuffels, B. (2009). Information Design Journal, 18, 175-177.

Jamieson, S. (2004). Likert scales: how to (ab)use them. Medical Education, 38, 1212-1218.

Lakatos, I. (1978). The Methodology of Scientific Research Programs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Likert, R. (1932). A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 140, 1-55.

Norman, G. (2010). Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in Health Science Education, 15, 625-632.

Zenker, F. (2007). Pragma-Dialectic’s Necessary Conditions for a Critical Discussion. In Hansen, H. et al. (Eds.). Proceedings of the 7th Int. Conference of the Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation (OSSA), Windsor, ON, CD ROM.

Zenker, F. (2009). Ceteris Paribus in Conservative Belief Revision. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Zenker, F. (2010). Review of Eemeren, F.H. van, Garssen, B., & Meuffels, B. (2009). Cogency, 2 (1), 149-165.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply