Imaging Africa: Gorillas, Actors And Characters

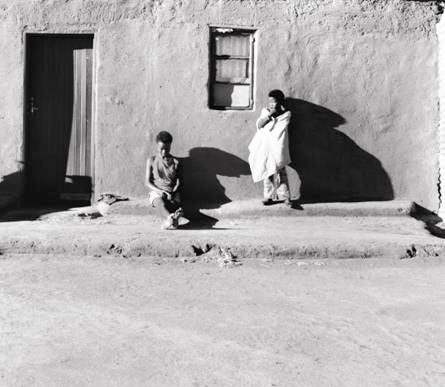

Africa is defined in the popular imagination by images of wild animals, savage dancing, witchcraft, the Noble Savage, and the Great White Hunter. These images typify the majority of Western and even some South African film fare on Africa.

Africa is defined in the popular imagination by images of wild animals, savage dancing, witchcraft, the Noble Savage, and the Great White Hunter. These images typify the majority of Western and even some South African film fare on Africa.

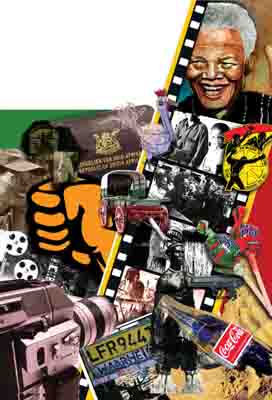

Although there was much negative representation in these films I will discuss how films set in Africa provided opportunities for black American actors to redefine the way that Africans are imaged in international cinema. I conclude this essay with a discussion of the process of revitalisation of South African cinema after apartheid.

The study of post-apartheid cinema requires a revisionist history that brings us back to pre-apartheid periods, as argued by Isabel Balseiro and Ntongela Masilela (2003) in their book’s title, To Change Reels. The reel that needs changing is the one that most of us were using until Masilela’s New African Movement interventions (2000a/b;2003). This historical recovery has nothing to do with Afrocentricism, essentialism or African nationalisms. Rather, it involved the identification of neglected areas of analysis of how blacks themselves engaged, used and subverted film culture as South Africa lurched towards modernity at the turn of the century. Names already familiar to scholars in early South African history not surprisingly recur in this recovery, Solomon T. Plaatje being the most notable.

It is incorrect that ‘modernity denies history, as the contrast with the past – a constantly changing entity – remains a necessary point of reference’ (Outhwaite 2003: 404). Similarly, Masilela’s (2002b: 232) notion that ‘consciousness of precedent has become very nearly the condition and definition of major artistic works’ calls for a reflection on past intellectual movements in South Africa for a democratic modernity after apartheid. He draws on Thelma Gutsche’s (1972) assumption that film practice is one of the quintessential forms of modernity. However, there could be no such thing as a South African cinema under the modernist conditions of apartheid. This is where modernity’s constant pull towards the future comes into play (Outhwaite 2003). Simultaneous with the necessary break from white domination in film production, or a pull towards the future away from the conditions of apartheid, South Africans will need to re-acquire the ‘consciousness of precedent’, of the intellectual and cultural heritage of the New African Movement, such as is done in Come See the Bioscope (1997) which images Plaatjes’s mobile distribution initiative in the teens of the century. The Movement’s intellectual and cultural accomplishments in establishing a national culture in the context of modernity is a necessary point of reference for the African Renaissance to establish a national cinema in the context of the New South Africa (Masilela 2000b). Following Masilela (ibid.: 235), debates and practices that are of relevance within the New African Movement include:

1. the different structures of portrayal of Shaka in history by Thomas Mofolo and Mazisi Kunene across generic forms and in the context of nationalism and modernity;

2. the discussion and dialogue between Solomon T. Plaatje, H.I.E. Dhlomo, R.V. Selope Thema, H. Selby Msimang and Lewis Nkosi about the construction of the idea of the New African, concerning national identity and cultural identity;

3. the lessons facilitated by Charlotte Manye Maxeke and James Kwegyir Aggrey in making possible the connection between the New Negro modernity and New African modernity;

4. the discourse on the relationship between Marxism and modernity within the context of the Trotskyism of Ben Kies and I.B. Tabata and the Stalinism of Michael Harmel, Albert Nzula and Yusuf Mohammed Dadoo; and

5. the feminist political practices of Helen Joseph, Lilian Ngoyi, Phyllis Ntanatala and others.

Read more

Reshaping Remembrance ~ ‘In Ferocious Anger I Bit The Hand That Controls’ – The Rise Of Afrikaans Punk Rock Music

On a night in 2006, a Cape Town’s night club, its floor littered with cigarette butts, plays host to an Afrikaner (sub)cultural gathering. Guys with seventies’ glam rock hairstyles, wearing old school uniform-like blazers decorated with a collection of pins and buttons and teamed up with tight jeans, sneakers and loose shoelaces keep one eagerly awaiting eye on the set stage and another on the short skirted girls. Before taking to the stage, the band, Fokofpolisiekar, entices the audience with the projection of their latest music video for the acoustic version of their debut hit single released two years before and entitled ‘Hemel op die platteland’.

On a night in 2006, a Cape Town’s night club, its floor littered with cigarette butts, plays host to an Afrikaner (sub)cultural gathering. Guys with seventies’ glam rock hairstyles, wearing old school uniform-like blazers decorated with a collection of pins and buttons and teamed up with tight jeans, sneakers and loose shoelaces keep one eagerly awaiting eye on the set stage and another on the short skirted girls. Before taking to the stage, the band, Fokofpolisiekar, entices the audience with the projection of their latest music video for the acoustic version of their debut hit single released two years before and entitled ‘Hemel op die platteland’.

In tune with the melancholy sound of an acoustic guitar, the music video kicks off with the winding of an old film reel revealing nostalgic stock footage of a long gone era. Well-known images make the audience feel a sense of estrangement by means of ironic disillusionment: the sun is setting in the Cape Town suburb of Bellville. Seemingly bored, the five members of Fokofpolisiekar hang around the Afrikaans Language Monument. Against the backdrop of a blue-grey sky, the well-known image of a Dutch Reformed church tower flashes in blinding sunlight. Smiling white children play next to swimming pools in the backyards of well-to-do suburbs and on white beaches while the voice of the lead singer asks:

can you tighten my bolts for me? / can you find my marbles for me? / can you stick your idea of normal up your ass? / can you spell apathy? can someone maybe phone a god / and tell him we don’t need him anymore / can you spell apathy? (kan jy my skroewe vir my vasdraai? / kan jy my albasters vir my vind? / kan jy jou idee van normaal by jou gat opdruk? / kan jy apatie spel? kan iemand dalk ’n god bel / en vir hom sê ons het hom nie meer nodig nie / kan jy apatie spel?)

And whilst the home video footage of a family eating supper in a green acred backyard is sharply contrasted with images of broken garden chairs in an otherwise empty run-down backyard, the theme of the song resonates ironically in the chorus: ‘it’s heaven on the platteland’ (‘dis hemel op die platteland’). On the dirty floor of the night club, a young white Afrikaans guy kills his Malboro cigarette and takes a sip of his lukewarm Black Label beer, watching more video images of morally grounded suburb, school and church and relates to the angry words of the vocalist:

And whilst the home video footage of a family eating supper in a green acred backyard is sharply contrasted with images of broken garden chairs in an otherwise empty run-down backyard, the theme of the song resonates ironically in the chorus: ‘it’s heaven on the platteland’ (‘dis hemel op die platteland’). On the dirty floor of the night club, a young white Afrikaans guy kills his Malboro cigarette and takes a sip of his lukewarm Black Label beer, watching more video images of morally grounded suburb, school and church and relates to the angry words of the vocalist:

‘regulate me […] place me in a box and mark it safe / then send me to where all the boxes/idiots go / send me to heaven I think it’s on the platteland’ (‘reguleer my, roetineer my / plaas my in ’n boks en merk dit veilig / stuur my dan waarheen al die dose gaan / stuur my hemel toe ek dink dis in die platteland / dis hemel op die platteland’).

As the video draws to a close, the young man sees the ironic use of the partly exposed motto engraved on the path to the Language Monument: ‘This is us’. He has never visited the Language Monument, but he agrees with what he just saw and because he feels as though he just paged through old photo albums (only to come to the disillusioned conclusion that everything has been all too burlesque) he puts his hands in the air when the band takes to the stage with the lead singer commanding:

‘Lift your hands to the burlesque […] We want the attention / of the brainless crowd / We want the famine the urgent lack of energy / We are in search of the search for something / We are empty, because we want to be’ (‘Rys jou hande vir die klug […] Ons soek die aandag / van die breinlose gehoor / Ons soek die hongersnood die dringende gebrek aan energie / Ons is op soek na die soeke na iets / Ons is leeg, want ons wil wees’. Read more

Prophecies And Protests ~ Ubuntu And Communalism In African Philosophy And Art

During my efforts to set up dialogues between Western and African philosophies, I have singled out quite a number of subjects on which such dialogues are useful and necessary. Recently I have stated in an essay that three themes in the African way of thought have become especially important for me:

During my efforts to set up dialogues between Western and African philosophies, I have singled out quite a number of subjects on which such dialogues are useful and necessary. Recently I have stated in an essay that three themes in the African way of thought have become especially important for me:

1.1 The basic concept of vital force, differing from the basic concept of being, which is prevalent in Western philosophy;

1.2. The prevailing role of the community, differing from the predominantly individualistic thinking in the West;

1.3. The belief in spirits, differing from the scientific and rationalistic way of thought, which is prevalent in Western philosophy (Kimmerle 2001: 5).

In these fields of philosophical thought there are contributions from African philosophers, which differ in a very characteristic way from Western thinking. Therefore in a dialogue on these themes a special enrichment of Western philosophy is possible. In the following text I want to clarify this possibility by concentrating on two notions, which have a specific meaning in the context of African philosophy. To discuss the notions of ubuntu and communalism means working out some important aspects of the second theme. The community spirit in African theory and practice is philosophically concentrated in notions such as ubuntu and communalism. But the concept of vital force, which is mentioned in the first theme, will play a certain role, too. We find the stem –ntu, which expresses the concept of vital force in many Bantu-languages, also in ubu–ntu. For a more detailed explanation of ubuntu, I will depend mainly on Mogobe B. Ramose’s book, which gives the most comprehensive explanation of the philosophical impact of this notion (Ramose 1999). The concept of communalism is explained in the context of the political philosophy of Leopold S. Senghor and other political leaders of African countries in the struggle for independence (Senghor 1964). A vehement critic of that theory is a Kenyan political scientist, V.G. Simiyu (Simiyu 1987). For a philosophical evaluation of this controversy I will refer to the articles and books of Maurice Tschiamalenga Ntumba, Joseph M. Nyasani, and Kwame Gyekye, dealing with the relation between person and community (Ntumba 1985 and 1988; Nyasani 1989; Gyekye 1989 and 1997).

The Purchase Of The Farm Braklaagte By The Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa – Whose Land Is It Anyway? (1908-1935)

Braklaagte, registered as farm number 168 on the Transvaal farm register (the number was changed in the second half of the twentieth century to JP-90), was 3,152 morgen and 529 square rood in size, which is equal to 2,700.5441 ha in metric measurements.

The first title deed to the farm was registered in October 1874 in the name of Diederik Jacobus Coetzee. Ownership of the farm was transferred several times to other white farmers. W.M. Beverley was the last white owner before the farm was bought by the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa.

In 1906 a dispute arose in the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa tribe of Dinokana in Moiloa’s Reserve between Abraham Pogiso Moiloa and Israel Keobusitse Moiloa. When Abraham’s father, Ikalafeng, had died in 1893 he was a minor and Israel, Ikalafeng’s younger brother, would for a number of years act as regent. When Israel had to hand over the bokgosi (chieftainship) to Abraham in 1906 differences arose between them. A section of the tribe, led by Israel, moved eastward and settled at Leeuwfontein.

Already in 1876 Leeuwfontein had been bought for the tribe by chief Sebogodi Moiloa of Dinokana at the price of 200 head of large cattle, equivalent to about £1,000, but the transfer of the farm to the tribe had not yet been effected. ‘Quite an exodus’ of the Bahurutshe ba ga Moiloa took place from Dinokana to Leeuwfontein and by 1907 the majority of Israel’s adherents had settled there.

Read more

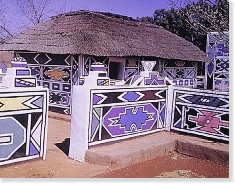

The Ndebele Nation

12-05-2015 ~ With an Introduction by Milton Keynes

The Ndebele of Zimbabwe, who today constitute about twenty percent of the population of the country, have a very rich and heroic history. It is partly this rich history that constitutes a resource that reinforces their memories and sense of a particularistic identity and distinctive nation within a predominantly Shona speaking country. It is also partly later developments ranging from the colonial violence of 1893-4 and 1896-7 (Imfazo 1 and Imfazo 2); Ndebele evictions from their land under the direction of the Rhodesian colonial settler state; recurring droughts in Matabeleland; ethnic forms taken by Zimbabwean nationalism; urban events happening around the city of Bulawayo; the state-orchestrated and ethnicised violence of the 1980s targeting the Ndebele community, which became known as Gukurahundi; and other factors like perceptions and realities of frustrated economic development in Matabeleland together with ever-present threats of repetition of Gukurahundi-style violence—that have contributed to the shaping and re-shaping of Ndebele identity within Zimbabwe.

The Ndebele history is traced from the Ndwandwe of Zwide and the Zulu of Shaka. The story of how the Ndebele ended up in Zimbabwe is explained in terms of the impact of the Mfecane—a nineteenth century revolution marked by the collapse of the earlier political formations of Mthethwa, Ndwandwe, and Ngwane kingdoms replaced by new ones of the Zulu under Shaka, the Sotho under Moshweshwe, and others built out of Mfecane refugees and asylum seekers. The revolution was also characterized by violence and migration that saw some Nguni and Sotho communities burst asunder and fragmenting into fleeing groups such as the Ndebele under Mzilikazi Khumalo, the Kololo under Sebetwane, the Shangaans under Soshangane, the Ngoni under Zwangendaba, and the Swazi under Queen Nyamazana. Out of these migrations emerged new political formations like the Ndebele state, that eventually inscribed itself by a combination of coercion and persuasion in the southwestern part of the Zimbabwean plateau in 1839-1840. The migration and eventual settlement of the Ndebele in Zimbabwe is also part of the historical drama that became intertwined with another dramatic event of the migration of the Boers from Cape Colony into the interior in what is generally referred to as the Great Trek, that began in 1835. It was military clashes with the Boers that forced Mzilikazi and his followers to migrate across the Limpopo River into Zimbabwe.

As a result of the Ndebele community’s dramatic history of nation construction, their association with such groups as the Zulu of South Africa renowned for their military prowess, their heroic migration across the Limpopo, their foundation of a nation out of Nguni, Sotho, Tswana, Kalanga, Rozvi and ‘Shona’ groups, and their practice of raiding that they attracted enormous interest from early white travellers, missionaries and early anthropologists. This interest in the life and history of the Ndebele produced different representations, ranging from the Ndebele as an indomitable ‘martial tribe’ ranking alongside the Zulu, Maasai and Kikuyu, who also attracted the attention of early white literary observers, as ‘warriors’ and militaristic groups. This resulted in a combination of exoticisation and demonization that culminated in the Ndebele earning many labels such as ‘bloodthirsty destroyers’ and ‘noble savages’ within Western colonial images of Africa.

Ndebele History

Ndebele History

With the passage of time, the Ndebele themselves played up to some of the earlier characterizations as they sought to build a particular identity within an environment in which they were surrounded by numerically superior ‘Shona’ communities. The warrior identity suited Ndebele hegemonic ideologies. Their Shona neighbours also contributed to the image of the Ndebele as the militaristic and aggressive ‘other’. Within this discourse, the Shona portrayed themselves as victims of Ndebele raiders who constantly went away with their livestock and women—disrupting their otherwise orderly and peaceful lives. A mythology thus permeates the whole spectrum of Ndebele history, fed by distortions and exaggerations of Ndebele military prowess, the nature of Ndebele governance institutions, and the general way of life.

My interest is primarily in unpacking and exploding the mythology within Ndebele historiography while at the same time making new sense of Ndebele hegemonic ideologies. My intention is to inform the broader debate on pre-colonial African systems of governance, the conduct of politics, social control, and conceptions of human security. Therefore, the book The Ndebele Nation (see: below) delves deeper into questions of how Ndebele power was constructed, how it was institutionalized and broadcast across people of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. These issues are examined across the pre-colonial times up to the mid-twentieth century, a time when power resided with the early Rhodesian colonial state. I touch lightly on the question of whether the violent transition from an Ndebele hegemony to a Rhodesia settler colonial hegemony was in reality a transition from one flawed and coercive regime to another. Broadly speaking this book is an intellectual enterprise in understanding political and social dynamics that made pre-colonial Ndebele states tick; in particular, how power and authority were broadcast and exercised, including the nature of state-society relations.

What emerges from the book is that while the pre-colonial Ndebele state began as an imposition on society of Khumalo and Zansi hegemony, the state simultaneously pursued peaceful and ideological ways of winning the consent of the governed. This became the impetus for the constant and ongoing drive for ‘democratization,’ so as contain and displace the destructive centripetal forces of rebellion and subversion. Within the Ndebele state, power was constructed around a small Khumalo clan ruling in alliance with some dominant Nguni (Zansi) houses over a heterogeneous nation on the Zimbabwean plateau. The key question is how this small Khumalo group in alliance with the Zansi managed to extend their power across a majority of people of non-Nguni stock. Earlier historians over-emphasized military coercion as though violence was ever enough as a pillar of nation-building. In this book I delve deeper into a historical interrogation of key dynamics of state formation and nation-building, hegemony construction and inscription, the style of governance, the creation of human rights spaces and openings, and human security provision, in search of those attributes that made the Ndebele state tick and made it survive until it was destroyed by the violent forces of Rhodesian settler colonialism.

The book takes a broad revisionist approach involving systematic revisiting of earlier scholarly works on the Ndebele experiences in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and critiquing them. A critical eye is cast on interpretation and making sense of key Ndebele political and social concepts and ideas that do not clearly emerge in existing literature. Throughout the book, the Ndebele historical experiences are consistently discussed in relation to a broad range of historiography and critical social theories of hegemony and human rights, and post-colonial discourses are used as tools of analysis.

Empirically and thematically, the book focuses on the complex historical processes involving the destruction of the autonomy of the decentralized Khumalo clans, their dispersal from their coastal homes in Nguniland, and the construction of Khumalo hegemony that happened in tandem with the formation of the Ndebele state in the midst of the Mfecane revolution. It further delves deeper into the examination of the expansion and maturing of the Ndebele State into a heterogeneous settled nation north of the Limpopo River. The colonial encounter with the Ndebele state dating back to the 1860s culminating in the imperialist violence of the 1890s and the subsequent colonization of the Ndebele in 1897 is also subjected to consistent analysis in this book.

What is evident is that the broad spectrum of Ndebele history was shot through with complex ambiguities and contradictions that have so far not been subjected to serious scholarly analysis. These ambiguities include tendencies and practices of domination versus resistance as the Ndebele rebelled against both pre-colonial African despots like Zwide and Shaka as well as against Rhodesian settler colonial conquest. The Ndebele fought to achieve domination, material security, political autonomy, cultural and political independence, social justice, human dignity, and tolerant governance even within their state in the face of a hegemonic Ndebele ruling elite that sought to maintain its political dominance and material privileges through a delicate combination of patronage, accountability, exploitation, and limited coercion.

The overarching analytical perspective is centred on the problem of the relation between coercion and consent during different phases of Ndebele history up to their encounter with colonialism. Major shifts from clan to state, migration to settlement, and single ethnic group to multi-ethnic society are systematically analyzed with the intention of revealing the concealed contradictions, conflict, tension, and social cleavages that permitted conquest, desertions, raiding, assimilation, domination, and exploitation, as well as social security, communalism, and tolerance. These ideologies, practices and values combined and co-existed uneasily, periodically and tendentiously within the Ndebele society. They were articulated in varied and changing idioms, languages and cultural traditions, and underpinned by complex institutions. Read more

The International Institute For Development And Ethics

The International Institute For Development And Ethics (IIDE) is an innovative institute that stimulates collaboration between the North and the South in study and action in ethical development, locally and globally. Since 2004 the IIDE has been represented in Africa and Europe by two mutually dependent entities. They operate as an intermediary between universities and the broader society by creating linkages and alliances between different universities and between universities and external parties. It aims to add value for all parties in relation to content and finance, realised through:

The International Institute For Development And Ethics (IIDE) is an innovative institute that stimulates collaboration between the North and the South in study and action in ethical development, locally and globally. Since 2004 the IIDE has been represented in Africa and Europe by two mutually dependent entities. They operate as an intermediary between universities and the broader society by creating linkages and alliances between different universities and between universities and external parties. It aims to add value for all parties in relation to content and finance, realised through:

* initiating and supporting social entrepreneurial approaches in development;

* research; and

* teaching and training.

It is the mission of the IIDE to serve society by bridging the proverbial gap between theory and practice, between university and society. Being aware that effective development is unthinkable without both practical and scientific expertise, the IIDE brings together practitioners and academics in order to utilise good practices from both environments.

Although the IIDE is a fully independent organisation without ties to any religious denomination, it takes Christian principles and values as its primary source of guidance and reference. As such, its views on Christian social responsibility lead the way to its vision, its mission and the concrete services and products it wishes to render for the benefit of society.

Contact information is available at www.iide-online.org

Now online:

Proceedings of the 19th Annual Working Conference of the IIDE – 6 – 9 May 2014 – Mark Rathbone, Fabian von Schéele & Sytse Strijbos (Editors)

Work in Progress:

Proceedings of the 17th Annual Working Conference of the IIDE Vol. I – May 2011 – Lucius Botes, Roel Jongeneel & Sytse Strijbos (Editors)

Proceedings of the 17th Annual Working Conference of the IIDE Vol. II – May 2011 – Christine G. van Burken & Darek M. Haftor (Editors)

Read more