ISSA Proceedings 2010 – Employing The Toulmin’s Model In Rhetorical Education

No comments yet 1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Rhetoric is the art of audience directed public speaking (Škarić 2003). There have been numerous definitions of rhetoric throughout history, but in either case all involve speaking in front of the audience. These two key concepts determine all other aspects of rhetorical theory, pedagogy and finally practice. This paper [i] explores the connection between rhetorical theory, developed both by ancient Greek scholars and modern authors, and rhetorical pedagogy. The paper also validates the connection of theory and pedagogy on examples from rhetorical practice. This is also an attempt to combine Aristotle’s notion of enthymeme and Toulmin’s argumentation model by emphasizing their similarities while proposing Toulmin’s model as a teaching and learning device, as well as an evaluation instrument for public speaking instructors. The analyzed speech examples belong to two groups; the first group includes speeches delivered at final presentation at School of Rhetoric in Croatia and the second those delivered in the Croatian Parliament.

In Classical Greece, the general belief was that rhetoric was the skill requiring special education and training. It was the integral part of classical education and remained part of the European educational heritage. Five Rhetorical Canons (Inventio, Dispositio, Elocutio, Memoria and Actio) provided guidelines both for rhetorical pedagogy and practice. Modern authors put emphasis on rhetorical practice by saying that the abilities of the good rhetorician cannot be developed merely by being talked about; they must be actively undertaken in practice (Jost and Olmsted 2004, p. xv). This paper attempts to follow that principle in teaching practice at The School of Rhetoric ‘Ivo Škarić’[ii] by including not only lectures, but also active participation in terms of classical mentoring during the process of creating a persuasive speech.

The aim of persuasive speech is to change attitudes, beliefs and opinions of the audience. It is believed that this is the most challenging type of public speaking since the speaker has to support and deliver his/her speech so to provoke an adequate reaction – acceptance by the audience. Persuasive speech reaches its goal through various means – the claim has to be supported by evidence, the speech needs to have a proper outline and polished delivery, and the speaker needs to believe that the topic of the speech will be accepted.

It was Aristotle who defined rhetoric within persuasive framework by saying that the function of rhetoric is to see the available means of persuasion in each case (On Rhetoric, 1.1, 1355b). It was again Aristotle who listed the means of persuasion by saying: All people are persuaded either because as judges they themselves are affected in some way or because they suppose the speakers have certain qualities or because something has been logically demonstrated (On Rhetoric, 3.1, 1403b).

The trichotomy of pathos, ethos and logos determined in classical Greece is still employed today. It is not uncommon to come across contemporary literature on public speaking and persuasion that explores the appeal to emotion, and even finding authors claiming that when persuasion is the end, passion also must be engaged (Lucas 2001). Ethics is an inevitable element in public (rhetorical) speaking. Again, Aristotle emphasized this point by saying: for it is not the case, as some of the handbook writers propose in their treatment of the art, that fair-mindedness [epieikeia] on the part of the speaker makes no contribution to persuasiveness;rather, character is almost, so to speak, the most authoritative form of persuasion (On Rhetoric, 1.2, 1356a).

One should not underestimate the importance of the relation between the two appeals. It is not unethical, as one may think, to use supporting material that appeals to emotions or emotionally tinted language in persuasive speech, especially when topics of persuasive speeches tend to address rather emotional issues. However, since unethical use of emotion in public speaking tends to arise quite often, emotions and ethics have started to be perceived as opposites. When searching for a speech enriched by pathos, the speech delivered by Hitler should not be the first example, but rather the ones delivered by Winston Churchill, Martin Luther King or Mother Theresa.

The third appeal is the appeal to logic, which means giving evidence and constructing argument through the principal processes of reasoning in order to support the claims of persuasive speeches. Types of evidence, their organization and relations can generally be called the argumentation of persuasive speeches. The term argumentation is a term often used in various contexts sharing certain common points, but not always belonging to the same category. This paper considers argumentation a process in which, to a particular audience, the proposition rationally becomes very probable truth. Arguments are elements of argumentation that support the claim and are milestones in the argumentation process. Rhetoric employs the process of reasoning that, either explicitly or implicitly, connects non-technical arguments with the proposition in order to confirm and persuade the matters perceived by the audience as disputable. This is why rhetorical argumentation is a special branch of argumentation. The importance of the argument layout for both educational and evaluation purposes will be further discussed later in this paper.

2. Aristotle’s Persuasive Enthymeme

Enthymeme as a form naturally belongs to rhetoric just as syllogism belongs to logic or to be more precise to dialectics. Once again Aristotle’s definitions and clarifications will be employed in order to determine the field of rhetorical argumentation so to explore contemporary argumentation schemes in more detail.

In his attempt to define the scope and field of rhetoric, Aristotle stated his opinion about preceding works: these writers say nothing about enthymemes, which is the “body” of persuasion (On Rhetoric, 1.1, 1354a) pointing out the importance of enthymeme for rhetorical persuasion or, in the terms explored in this paper, rhetorical argumentation. He draws a line between rhetoric and dialectics by claiming they are counterparts, implicitly pointing out the diferentia specifica of the two philosophical disciplines: [it is clear] that it is a function of one and the same art to see both the persuasive and the apparently persuasive, just as [it is the function] in dialectic [to recognize] both a syllogism and an apparent syllogism (On Rhetoric, 1.1, 1355b). He further continues to explicate the difference between syllogism utilized in dialectics as opposed to rhetorical enthymeme, but first makes an important remark about reasoning in general describing it as a cognitive ability of every human being. Cognitive processes we call reasoning are a universal human ability employed regardless of the degree of certainty. For it belongs to the same capacity both to see the true and what resembles the true, and at the same time humans have a natural disposition for the true and to a large extent hit on the truth; thus an ability to aim at commonly held opinions [endoxa] is a characteristic of one who also has a similar ability in regard to the truth (On Rhetoric, 1.1, 1355a).

It is not important whether the premises are true or probably true, the conclusions are made in a similar way. That is why rhetoric ‘needs’ dialectics to learn, adapt or even imitate the processes today usually ascribed to logic. Still, different start positions, as noted in Aristotle, should not be ignored: to show on the basis of many similar instances that something is so is in dialectic induction, in rhetoric paradigm; but to show that if some premises are true, something else [the conclusion] beyond them results from these because they are true, either universally or for the most part, in dialectic is called syllogism and in rhetoric enthymeme (On Rhetoric, 1.2, 1356b).

He further defines the enthymeme, calling it a rhetorical syllogism, and once again emphasizing its use as means of persuasion. And all [speakers] produce logical persuasion by means of paradigms or enthymemes and by nothing other than these. (On Rhetoric, 1.2, 1356b)

So, when focusing on enthymeme as a rhetorician’s instrument in persuasion, it should be noted that it cannot have the same validating strength of the syllogism. However, enthymeme is much more effective for the speech delivery (Actio) when addressing a crowd (due to brevity) (Olmsted 2006). Other advantages of enthymeme, since there are no certainties, is its ability to offer insight into both sides of a dispute and develop critical thinking; another important dimension of education.

3. Toulmin’s Model in Rhetorical Pedagogy

When writing The Uses of Argument (1958), Toulmin himself did not have aspirations to expound a theory of rhetoric or argumentation, nor to establish the analytical model that came to be called the Toulmin model (Toulmin 2003, p. vii). Nevertheless, the model’s impact on argumentation theory is immense. The model itself inspired numerous scholars and provoked various debates between the followers of both formal and informal logic.

However, it should be pointed out that the approach to Toulmin’s model rarely left scholarly debates and tackled the lively examples of public speeches (Hitchcock & Verheij 2006). It has often been forgotten that Toulmin’s model offers comprehensive layout for rhetorical argumentation and can be used as a powerful teaching device.

In rhetorical pedagogy, there are three main advantages of Toulmin’s model. The visual character of the model, sometimes called a scheme due to the visual characteristics, is the first advantage noted during the learning process. Since humans are visually oriented, it is clear that such information input facilitates learning, and, what is more, visualization is one of the most frequent strategies for effective listening (Škarić 2003). The five rhetorical canons state that the speaker arranges the material after determining the topic and gathering the material (Inventio). The model facilitates this stage by offering a simple and clear-cut layout used to determine the importance of data (ground) and backings in order to establish modal qualification.

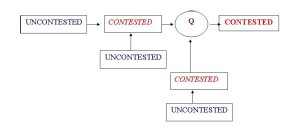

The second advantage is applicable to rhetorical education in particular, while the first one can be used more generally. It is necessary to discern uncontested and contested elements in argumentation or, in other words, the true and the probably true. The true elements, which do not require additional support, are grounds and backings, while the probably true elements are warrant, rebuttal and obviously the claim. The model makes clear distinction of the elements and thus becomes a powerful learning device.

Figure (1) Toulmin’s model with true and probably true elements

Finally, the third advantage of Toulmin’s model is easier recognition of argumentative procedures and fallacies in the argumentation process. This paper supports the assumption that both speaker and listener can benefit from the model. The model has a strong effect on both organization and clarity of the speech. It can help the audience to employ critical and logical thinking, and, if the audience is in fact persuaded, this persuasion will definitely have an important impact.

The relation between the model and the enthymeme is evident if perceived in the upper part of the model as an inference. A warrant can be expressed as a major premise of rhetorical syllogism (enthymeme), meaning that the warrant states a rule, a generalization or can be left implicit – as is the case when enthymeme’s data is the minor premise, an individual case, while the claim is a conclusion in the persuasive enthymeme achieving the speaker’s goal.

When ‘dissected’, the model, due to these enthymemic features, seems to ‘prefer’ deductive reasoning. Surely, it should not be concluded that other types of reasoning are forbidden, but the main inference, connecting the upper part of the model and leading to the claim (proposition), is rhetorical deduction. If rhetorical processes mimic the logical ones then rhetorical deduction must be acknowledged as the counterpart of logical deduction (valid inference from premises). Rhetorical deduction represented by enthymeme follows the validity of inference, but the major premise in enthymeme is certainly probable and not the absolute truth. Therefore, the syllogism consists of a true major premise and a true minor premise leading to a true conclusion. On the other hand, enthymeme includes a (very) probable major premise and a true minor premise which finally give a (very) probable conclusion.

4. Analysis of persuasive speeches within Toulmin’s model

Speech delivery is in fact the interplay of several different factors; speaker’s intention, the delivered text and the content that remains unspoken but implied between the speaker and the audience. In that way, public speeches may be perceived as unique verbal discourses. In the moment of delivery, the speaker does not only address the audience, but this particular audience determines the argumentation in the speech, and, therefore, the speaker adapts. However, it is the speaker’s responsibility, and the integral part of public speaker’s ethos, to examine all the elements of the argumentation during the dispositio phase.

When concentrating on argumentation and logic of a certain speech, the listener, either layman or professional is always involved in the process of translating the delivered speech (Actio) to the text defined during speech preparation (Elocutio). Moving from elocutio and returning to dispositio, apart from recognizing elements of argumentation, the listener must add everything that was implied in the delivery. Toulmin’s model aids this reconstruction due to the above mentioned advantages.

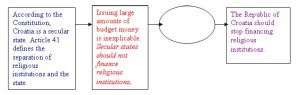

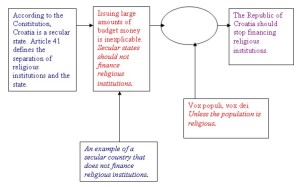

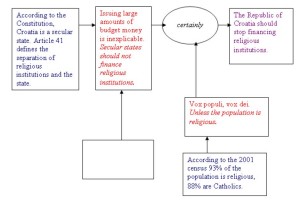

Translation of the delivered text back to the ‘Toulmin’s boxes’ was the method used in the analysis of speeches. The illustrations show argument’s layout in particular speeches and the reconstructed elements are brought in italics.

4.1. Speeches given at the Final Presentation at the School of Rhetoric

In the first example, the transcript is offered to illustrate the applied methodology. In the figures that illustrate argumentation layout, the sentences in italics represent the implied elements which were reconstructed for the analysis.[iii]

Example (1) Speech transcript 1

The Republic of Croatia should stop financing religious institutions. There are two aspects of this problem: political and economic. According to the Constitution, Croatia is a secular state. Article 41 states that all religious institutions and the state are separate. Therefore, issuing such large amounts of budget money is politically inexplicable. Some of you will perhaps remember the Latin proverb: Vox populi, vox Dei. Meaning: the voice of the people is God’s voice. According to the 2001 census 93% of the population is religious, 88% are Catholic. But it’s commonly known that true believers live their faith.

Independent Institute “Ivo Pilar” conducted a survey and it showed that only 12% of Croats attend religious ceremonies.

The speaker states a policy claim that the practice of giving 413 million HRK per year to all religious institutions in Croatia, money allocation depending on the number of believers/practitioners, should be changed. The ground for this claim is the highest legal act – the Constitution; the remaining logical predicate from the claim (financing) and from the ground (secular state) are connected in the warrant which is contested, but also bears a high degree of probability. There is no legal act that would forbid secular states to finance religious institutions, but it is implied as a topos, at least in the opinion of speakers and audience with liberal political views. It is difficult to suggest new piece of evidence to support this warrant other than the examples from other countries. In that way, the mentioned examples become rhetorical evidence (if the example is representative for given audience) which can raise the degree of certainty of the contested claim.

The topoi warrant which does not hold legal strength but is based on attitudes cannot be refuted with legal evidence. Namely, to break the Constitution would imply the state and religious institutions being a unity – but financing as such is not forbidden. Therefore, an exception is required to refute this general attitude. It is the speaker’s duty to do so since the audience must be informed about the opposing attitudes (Audiatur et altera pars!), and therefore the speaker anticipates possible rebuttal and refutes the rebuttal with another backing.

The rebuttal the speaker offers is in fact the opinion of the other side introduced by Latin proverb Vox populi, vox Dei, i.e. the population’s religious affiliation represents certain political strength in the state. If the population has strong religious affiliation the secularity of that state is definitely limited. In a country where the majority of citizens declare themselves to be atheists, it is not expected of the state to support religious institutions, but, nevertheless, a religious state cannot employ a wide application of the secularity principle.

Although the warrant itself is not the absolute truth, it seems that the rebuttal has its weaknesses. Therefore, the speaker, apparently not representing that side, attempts to strengthen the rebuttal with a backing – statistical data – by saying that, according to the Census, Croatian people undoubtedly determined their religious affiliation, especially regarding the Roman Catholic Church.

This backing could also be refuted since it does not support the generalization of the rebuttal but focuses on Croatia, could be rhetorically unnecessary and with a possible devastating outcome when introducing examples from other countries as the topics is about Croatia in particular. Finally, even if the rebuttal attempts to generalize, Croatia also needs to be included in the rebuttal when attacking the generalization expressed by the warrant. Once again we can see the strength of a rhetorical example.

Clearly the elements of Toulmin’s model are easily noted in this speech, meaning that the elocutio (textualisation) did not attempt to considerably mask dispositio. It can be concluded that this speech has a higher degree of rational, or better yet formal, argumentation and does not include a high level of persuasion. Considering the fact that persuasion often hides argumentation patterns by masking them into illustrative elements during elocutio, this can possibly be employed as an instrument for determining the degree of persuasion in the analysis of public speeches.

The model is only ‘stopped’ when expressing the rebuttal and determining modal qualification, but in the delivered speech the rebuttal must not remain ‘hanging’, it has to be refuted and the argumentation needs to be steered back to its initial course, making the claim rationally acceptable to the audience.

The basic reasoning process used in this example is rhetorical deduction, since the speaker used topos to connect the claim and the ground.

Example (2)

The second example shows that persuasive speeches often contain claims of policy since they should encourage an audience to act. Action can be encouraged by rational appeals or more effectively by emotional ones. A good speaker should profile his/her audience and decide on the type of argumentation most suitable for the given audience. One feature of audience profile is the level of emotionality, or whether a certain audience will be more or less susceptible to emotional corroborations. A very informative topic can quite often encourage an audience to act. Revealing less known facts about certain social situations can cause shock and disbelief, and a skilful speaker knows how to develop argumentation further after gaining the trust of an audience. However, the strongest argument should not be brought forward at the beginning. For the given audience, the strongest argument is the one carrying the greatest emotional weight. The speaker decides to commence with rational argumentation in which the process of the emotional action begins:

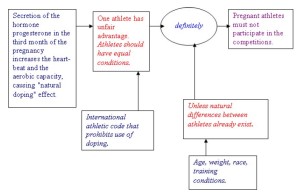

It cannot be disputed that doping is not fair or that it creates differences between athletes, and, after we learn about the influence of progesterone hormone on athletes in their first trimester, we are convinced that the pregnant athletes are doped.

The speaker does not see the need to support the warrant, providing such support would be redundant in this case. Again, there is the warrant of generalization at work: doping should not be present at sports events/athletes have to have equal conditions. So, never present and all have to have.

As shown in the example, the persuasion completely took over the process of explaining the claim since the speaker has no need to state the counter-argument. It can be claimed that the general belief is that all athletes competing in any sport should and are considered equal. However, rational rhetorical argumentation should be able to find that kind of objection, even though the persuasive speech loses its strength if the objections are stated explicitly. When considering the objections, they can be found in existing differences among athletes (e.g. race, weight etc.), but to state that objection in the elocutio phase is rhetorically inefficient. The stated differences are considered inevitable and are minimized in certain sports where they might be crucial for the results (e.g. making ranks or categories).

After the speaker successfully backed her claim from a sporting point of view, she moves on to the one determined as emotional as its very name: child’s point of view. The speaker offers examples of various athletes who were winning and breaking records while being pregnant and only to have abortions after a competition. The audience is left with an unspoken fact: the pregnancies were planned for one reason only – to achieve greater score. This is when the speaker includes emotional support: she takes over the topos of an unborn child’s right to live. The audience is not allowed to question the truth of that topos, although it is rationally questionable. This is when the counter-argument is stated: why should the athletes who are pregnant but also want to keep their child be banned from competing? Should they be victims of the said pregnancy manipulations? Emotional argumentation is opposed by the rational one, and the speaker is aware that the argument should be refuted rationally. She decides to use the tactics of fine differentiation: physical activity that is beneficial for pregnant women is not related to physical strain which athletes have to undergo even if they want average results. So, physical strain that logically cannot be equal to physical activity acts as a powerful junction of these two argumentation flows. The speaker’s audience is now convinced, both rationally and emotionally, that pregnant athletes should not be allowed to compete.

4.2. Speeches delivered in the Croatian Parliament

The following examples (3), (4), (5), (6) were extracted from the debate about the Bill on Assisted Reproductive Technology (July, 2009). The bill proposer is the Health Minister, the first bill opposer is Chairperson of the Gender Equality Committee and the second bill opposer is the representative of the Social Democratic Party’s Deputy Club (the largest oposition party).[iv]

Bill proposer consciously creates a large fallacy – he overlooks alternatives. It would be rather useful to follow classical rhetorical principle of stating the counter-argument (rebuttal) since the proper refutation intensifies the proposer’s claim.

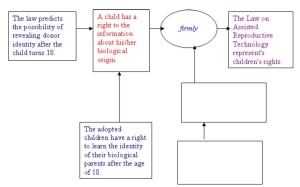

Health Minister attempts to employ analogically-deductive reasoning within the specific argumentation line. General claim in the parliamentary debate is that the bill should be accepted. First he says that the Law on Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) protects children’s rights. This claim is explicitly a claim of fact and implicitly a claim of value. The law will protect children’s rights by introducing a new regulation that a child can, after turning 18, require information about the donor’s identity.

When drawing analogy with current legal regulation stating the right of adopted children to reveal the identity of their biological parents when they become of full age, he tries to establish a warrant that would appear as a general rule; every child has a right to find information about their biological parents.

The Minister does not state the rebuttal since it is not in his best interest to refute his own claim (why would he give arguments to the Opposition?), but he forgets that parliamentary debate is, from a rhetorical perspective, just another debate in which the counter-argument should be anticipated.

For example, the Minister could have offered an exception to his rule (warrant) by stating that indeed every child has a right to access information about his/her biological parents unless that right will decrease the number of potential donors. This is a strong rebuttal and it is not easy to give such strong argument to the Opposition, especially when you are not certain about the possible refutation.

What he seemed to forget was the fact that reasoning by analogy proven to be quite useful in this kind of argumentation; to find examples of countries with similar regulations about revealing donor’s identity in which the number of potential donors did not decrease. The claim could even be stronger if he stated that Croatian donor practice should also be more advanced and that donors should be aware of both their rights and duties. Surely, the existing Family Law and other laws and regulations implicitly protect the donor so that reproductive donation cannot cause any financial problems. What remains open is the matter of anonymity, but here we witnessed a dispute about values, evidently the field of rhetoric.

Figure 7 – Toulmin’s model – speech example (4) (Bill opposer 1 – Chairperson of the Gender Equality Committee)

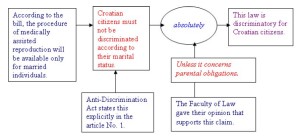

The Opposition can play the same game as the Minister, as demonstrated by the president of the Gender Equality Committee (4). If the Minister uses the analogy to connect the rights of adopted children and the rights of children conceived by ART, then the Opposition can use the analogy to point out that the bill discriminates unmarried couples.

The ground for this argumentation was the fact that legislation does overlook the possibility of ART treatments for unmarried couples and the speaker decides to support this analogy rationally, on the existing legal regulations, or specifically by the Anti-Discrimination Act. This support significantly strengthened the warrant, reflecting the speaker’s general attitude that Croatian citizens should not be discriminated according to their marital status.

In this case the Minister did not use a counter-argument for his warrant on universal rights of children to know who their parents are, but the opposing representative also did not state the possible rebuttal, since she considered her warrant an unquestionable truth. However, the Minister replies immediately by pulling an ace out of his sleeve – unmarried and married couples are not absolutely equal in front of the law. He stated the opinion of the Chair for Family Law at the Faculty of Law in Zagreb, which interprets the Family Law in the following manner: married and unmarried couples are equal in terms of rights and property, but not in terms of parenting. Namely, only a child born within a legal marriage automatically has a legal father, i.e. the mother’s husband. However, what remains controversial and what can be debated even further is the question of offering partial rights to couples and not leaving them the possibility to use ART treatment. It may be implicitly concluded that lex specialis (ART Law) amends for the current Government too liberal lex generalis, i.e. the Family Law, which regulates the existence and rights of unmarried couples.

Speech example (5) (Bill proposer –Health Minister)

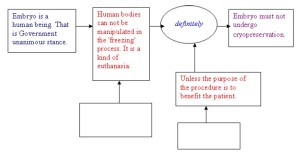

The dispute about the values concerning the ART is one of the paradigmatic debates between the left and right wing politicians – the question of abortion or moreover the right to abortion seems to emerge. More specifically, there is the problem of cryopreservation within the ART procedure and the side-effect of casting off the embryo surplus.

The ground that the Health Minister uses in his argumentation is the attitude of the centre-right government based on the stipulative definition of an embryo being a human being. The warrant itself becomes obvious, supporting the claim that the procedure of cryopreservation should be abandoned.

It is evident that this argumentation line is neither based on legal nor medical ground. What we see here is the conflict of values, i.e. opinion topoi. The Minister’s attitude is rather clear and firm – freezing the large number of embryos which will later be discarded equals euthanasia. However, the Minister finds exceptions since he believes that this approach will win him the support of general public.

Embryos can be frozen if a patient would benefit from that, i.e. if she is medically unable to be implanted according to the scheduled procedure. The Government’s starting point has always been a child and its rights, but at that moment the Government begins to represent the woman’s rights as well. Nevertheless, the woman is still perceived only as the ‘embryo carrier’ and only because she cannot be implanted at certain moment due to medical problems, the embryos will be frozen. That means that the embryos will be waiting for their ‘carrier’ to recover and their rights will be protected.

It is important to note here that the Opposition did not attempt to offer meaningful refutation, but they used a stratagem ad absurdum. The representative of the Opposition stated the possibility of a woman’s health worsening and the embryos remaining frozen after she passes away, and, in this case, the government would allow the embryos to be ‘killed’. The Minister replies following the same pattern – ‘the atomic bomb is also an option, but it will not be a part of the legislation.’

This all shows that Toulmin’s model can be used for the evaluation of political speeches since it facilitates the recognition of fallacies and confirms that, in parliamentary debates between left and right wing politicians, the argumentation is based on opinion topoi which can be contested, but the expressed topoi will qualify as the absolute truth to the members of a certain group. Serious argumentation should not be based on breaking the topos but finding the weak parts of the argumentation structure that these topoi (warrants) potentially generated.

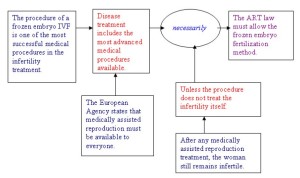

As a response to the Minister’s claim about cryopreservation, the representative of the largest Opposition party, also a doctor provides a completely opposite claim. He states that the cryopreservation procedure should be allowed since based on the fact that the procedure itself is rather modern and has proven extremely successful. He explicates his warrant, which is by all means a general one, that the treatment of all diseases should include the most advanced methods. The backing for that warrant is the attitude of the European Agency, an important authority in the current political context since Croatia is an EU accession country.

However, the ‘quick’ Minister finds the exception to the general warrant through anti-example which affects the entire argumentation stated by the SDP representative. There is nothing controversial about the fact that an illness should be cured with all the available means, but Minister points out that cryopreservation is not a medical procedure that cures infertility. In his witty response he says: A woman who conceives a child by medically assisted reproduction remains infertile and still cannot conceive naturally. The same applies to men.

Figure 9 – Toulmin’s model – speech example (6) (Bill opposer 2 – Representative of Social Democratic Party’s Deputy Club)

General conclusion of the argumentation seen in the Parliamentary debate is that the reasoning in most enthymemes is based on the opinion topos. Right political option, represented in our examples by the Health Minister, uses those topoi representing firm and stable conservative value system shared by right wing politicians and electorate. The problem in their argumentation is that all deductive conclusions are based on such topoi expressed in warrants, and such warrants overlook modern scientific achievements. On the other hand, left wing politicians are mistaken because they overlook the alternatives; the topoi they use do not have a moralizing tone, but are based on the principles of egality and provide equal rights for everyone. Actually, left politicians have one overall topos: all people have maximum rights and are equal among themselves. That general topos generates partial warrants suitable for specific claims stated during the debate. However, most often the warrants are rather weak, because, paradoxically, they are not strong enough to include basic values. That is why the right wing politicians often find strong rebuttals and support their claims efficiently.

5. Conclusion

The advantage that Toulmin’s model offers to learners, listeners and evaluators of persuasive speeches is the support for the layout of argument, insight into fallacies and the origin of a dispute (determining underlying topoi). The model is especially sensitive to recognition of fallacies, i.e. overlooking alternatives, or better yet, ignoring exceptions to the rule (the warrant) which have to be neutralized or refuted. The model also gives an efficient instrument to rationally examine argumentation from both sides, as it was evident in this analysis of the parliamentary debate, thus minimizing the analytics’ bias which would not be possible if only the speech transcript (Elocutio) was analyzed.

NOTES

[i] This work was supported by the Ministry of Science, Education and Sport (grant number 130-1300787-0789). The authors would also like to thank the School of Rhetoric ‘Ivo Škarić’ – students and colleagues who always encouraged inspiring discussions about the famous model, Ana Opačak and Željka Pleše for patience and help with translations, and finally to our professor Ivo Škarić (1933-2009) for making us think differently. As Carnegie said Fear not those who argue, but those who dodge. We try not to…

[ii] The School of Rhetoric was established in 1992 by late professor emeritus Ivo Škarić from the Department of Phonetics, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. The school takes place twice a year for a week. Classes are organized by a workshop principle in small groups guided by a mentor. During one week per term, students (high-school age) learn about public speaking principles and prepare persuasive speech. The best speeches are selected by the expert commission and then delivered at the final presentation where the audience choses the winning speech. The speeches used as examples in this paper are the winning speeches.

[iii] The later examples were not preceded by the transcripts. The first transcript was given to stress out the differences between elocutio and dispositio phase.

[iv] The debate took place in July 2009. The full video of the debate can be found at http://itv.sabor.hr/video/.

REFERENCES

Aristotle (2007). On Rhetoric: A Theory of Civic Discourse. (translated by George A. Kennedy) New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hitchcock, D. & Verheij, B. (Eds.) (2006). Arguing on the Toulmin Model: New Essays in Argument Analysis and Evaluation. Dordrecht: Springer.

Jost, W. & Olmsted, W. (Eds.) (2004). A Companion to Rhetoric and Rhetorical Criticism. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Lucas, S. E. (2001). The Art of Public Speaking. Boston: McGraw Hill.

Olmsted, W. (2006). Rhetoric: an historical introduction. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Škarić, I. (2003). Temeljci suvremenoga govorništva. Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

Toulmin, S. E. (2003). The Uses of Argument (updated edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply