ISSA Proceedings 1998 – Looking At Argumentation Through Communicative Intentions: Ways To Define Fallacies

No comments yet 1. American print media argumentation and the notion of fallacy

1. American print media argumentation and the notion of fallacy

The paper has three closely related purposes to fulfill. The first main purpose is to identify American print media arguers’ communicative strategies; establish a cause-effect relationship between the illocutionary forces of argumentative discourses as illocutionary act complexes and their perlocutionary effects; and, as stated in the title of the paper, to present ways to define fallacies by looking at argumentation through communicative intentions of the authors of the discourses. The second purpose is to present a tool with which it would be possible to describe the means by which emotional appeal is created. The third purpose is to make a clear distinction between an illocutionary force of asserting/claiming and that of stating, and demonstrate the importance of this distinction in the study of argumentation.

In order to identify fallacies, we should first make it clear how we define the notion of fallacy in this paper. To do that, we have to define the type of dialogue we deal with in the American print media. D. Walton identifies ten specific types of dialogue according to the goals parties seek to achieve. A dialogue is defined as “an exchange of speech acts between two speech partners in turn-taking sequence aimed at a collective goal” (Walton 1992: 19). With the exception of the genre of interview, whose analysis will not be a focus of our study since the goal of an interview is seeking information, not arguing points of view, American print media do not contain direct dialogues but rather are sites of a deferred type of dialogue where the two parties’ reactions are presented in monologues separated from each other in time and space. However, this type of dialogue allows American print media authors to carry on an ongoing discussion of various issues. The real target audience of an American print media arguer is not an “official” antagonist in discussion, but the reader who is presumed to be a real antagonist in dispute, since to communicate news and opinion to the reader are the two main mass media functions. The real goal of both parties in most American print media dialogues is not to arrive at the truth of a matter, but to win a dispute. In other words we witness in the American print media a deferred persuasion dialogue. In terms of extent to which the American print media deferred dialogue resembles the critical discussion in the format of a direct dialogue, three types of American print media discussion can be identified.

The first type of American print media discussion, the most similar to critical discussion, occurs in the genre of letters to the editor whose authors react directly either to an editorial or to another letter to the editor. The dialogue is focused on one specific topic, and the parties of the dialogue advocate opposite positions on the issue. Obviously, both parties in the discussion are rather concerned to defeat the official active opponent but the main goal, however, of either party still remains to achieve persuasion of the passive reader. The second type of American print media discussion is manifest on the Pro/Con section of a newspaper or magazine. Again, the discussion focuses on one particular topic. The arguers do not react directly to an opposing discourse because neither party is familiar with the particular discourse their discourse will be juxtaposed with. While they are only asked to submit a text in support of a position in the argument they advocate, because of the specificity of the topic, they often show good knowledge of opposing arguments and rebut them. The third type of American print media discussion may be reconstructed on a larger scale across various American print media sources. Publications can be found in different American newspapers or magazines that focus on a number of related issues, including an issue common to both opposing parties, but one will find almost no rebuttals of specific arguments contained in the opposing discourse. Obviously, the last type of American print media discussion is the least similar to the critical discussion we deal with in real dialogue.

In this paper we shall consider two discourses contained in two articles published in the Health magazine’s Pro/Con section (September 1993). According to our classification this discussion belongs to the second type of American print media discussion. Both parties’ primary goals are to achieve persuasion of the reader. That is why we ought to use a rhetorical audience-oriented discourse analysis rather than a dialectical resolution-oriented one. Since, therefore, our interest will be centered on the factors affecting the cogency of argumentative discourse, we will use the traditional “rhetorical” notion of fallacy where a fallacy is an argument that “seems to be valid but is not so” (Hamblin 1970: 12).

In seeking persuasion, every arguer develops a communicative strategy of persuasion. The key element of a communicative strategy is to choose targets of appeal and prioritize them. While there is a wide variety of targets of appeal, it is possible to identify three major ones: people’s reason, emotions, and aesthetic feeling. An appeal to people’s reason is based on the rational strength of argumentation. Emotional appeal is based on arousing in the reader or hearer various emotions ranging from insecurity to fear, from sympathy to pity. Aesthetic appeal is based on people’s appreciation of linguistic and stylistic beauty of the message, its stylistic originality, rich language, sharp humor and wit.

Rational appeal is effective in changing beliefs and motives of the audience because it directly affects human reason where beliefs are formed. Emotional appeal is persuasively effective because it exploits or runs on concerns, worries, and desires of the people. Aesthetic appeal is persuasively effective because, if successful, it changes people’s attitudes to the message and through the message to its author. People will be more willing to accept the author’s arguments after they have experienced the arguer’s giftedness as a writer or speaker of the message.

Obviously, there is nothing intrinsically wrong with emotional or aesthetic appeals. In fact, we believe that maximum persuasive effect can be achieved if an arguer uses all three of the appeals, his rational appeal being reinforced with appeals to emotions and aesthetic feeling of the people. Problems can arise when an arguer uses emotional and aesthetic appeals to avoid arguing issues at hand (Rybacki & Rybacki 1995: 143). Emotional and aesthetic appeals are an important part of the process of persuasion but we believe that in argumentation emotion or aesthetic creativity should not supplant reason. Our investigation will be based on the presumption that, unless in times of crises when an emotionally appealing message with no strong arguments provided to support the claims finds a ready response in a frustrated and/or exalted audience and is constantly repeated, persuasion based primarily or solely on appeal to emotions has a short-lasting effect. It is especially true when people read an argumentative message in a newspaper or magazine in a quiet atmosphere of their living room. In this case the author of such a message has to be particularly careful as to the logical structure of the message and validity of the arguments.

Having said that, let us ask ourselves two questions: Why do authors of American print media argumentative messages commit fallacies in their argumentation committing which they could easily avoid? Why in particular do they commit deliberate fallacies? We believe we may answer the questions this way. The reason why authors of American print media argumentative messages commit so many especially deliberate fallacies lies in the fact that in order to maximize the persuasive effect of the messages, these arguers often tend to adopt a communicative strategy to rely primarily on emotional and aesthetic appeals, not rational appeal, in their persuasion of the audience. What happens then is that logical neatness and impeccability of argumentation of the discourse are sacrificed for emotionality of the message and its attractiveness to the reader. As a result such a discourse may contain an abundance of fallacies in reasoning that in fact are fallacies of appeal.

To demonstrate the point we are in need of a comprehensive analysis that could cover both logical and linguistic or communicative aspects of the discourse. We are in need of an analytic instrument that could not only help expose discourse argumentation structure, but also show us how the arguer’s communication technique weaves into his discourse to increase its persuasiveness and why it may fail to do so due to a fallacy.

No discourse analysis, especially with an emphasis on fallacies, can be successfully performed without prior identification of the role of the discourse interpreter. How is the interpreter different from an ordinary audience member? To what extent is the interpreter willing to reconstruct unexpressed premises the discourse contains? Answers to those questions will determine whether this or that argument, this or that illocutionary act can be considered fallacious or merely weak.

When looking at a discourse the interpreter reads the message, identifies the chains of arguments presented in the message (logico-semantic analysis), identifies communicative intentions expressed by the author (pragma-stylistic analysis) and demands reasonable fulfillment of commitments the author must take producing this or that illocutionary act. The interpreter of the discourse is thus a recipient of the message whose only difference from an ordinary newspaper or magazine reader is that the interpreter does not only rely on his common sense in understanding argumentation but is equipped with an apparatus of the logico-semantic and pragma-stylistic analysis, and who, thus, is able to assess the author’s communicative intentions, identify fallacies, and make educated hypotheses as to the persuasiveness of the message. For the same reason that the goal of our discourse analysis is to assess a discourse impact on an ordinary reader, our analysis will not include maximal reconstruction of unexpressed premises but rather one that is most likely to be done by the reader.

2. Logico-semantic and pragma-stylistic analysis of discourses

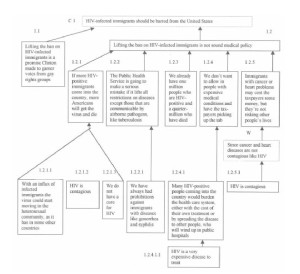

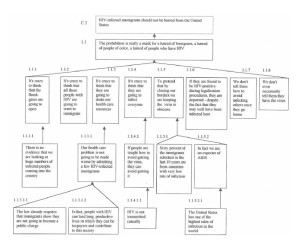

The authors of the articles to be analyzed discuss the United States Congress’s decision to maintain the prohibition for HIV-infected immigrants to enter the United States. The author of the first (left) discourse supports the decision and the author of the second (right) discourse strongly disagrees with it. It allows us to reconstruct the opposite main claims as C1 (Fig. 1) and C2 (Fig. 2), respectively. In the discourse argumentation structure schemes both claims are contoured with a dotted line as an indication that they are implied in the texts.

3. Logico-semantic analysis of the first discourse

The first discourse’s argumentation structure may be presented by the following argumentation scheme (Figure 1). From a logico-semantic point of view the discourse is well organized. There exists a strict distinction between different parts of the overall discourse argumentation manifested in the fact that the arguments the arguer uses in the first paragraph, with the exception of HIV is contagious, are not employed in the argumentation of the second paragraph and vice versa. It must also be noted that both the first and the second paragraphs begin with the most important arguments of their respective parts. These arguments are 1.2.1 and 1.1.4.1.1. The argumentation scheme shows that the arguments’ positions in the argumentation structure are different. Hence different are the functions the arguments are meant to fulfill. 1.2.1 is the strongest argument of the “third” row of arguments closest to the main explicitly expressed claim 1.2. This argument is the arguer’s second most important claim well supported by 1.2.1.1, 1.2.1.2, and 1.2.1.3. Its strength is in the fact that not only will the argument sound reasonable to the reader (appeal to reason) but it describes a life-threatening situation for the audience (emotional appeal to fear). The latter will be examined in the pragma-stylistic analysis of the discourse. 1.2.4.1.1, unlike 1.2.1, is situated at the very bottom of the vertical chain of arguments of the second paragraph. The importance of the argument is in the fact that it serves as a solid foundation for the second paragraph argumentation.

4. Pragma-stylistic analysis of the first discourse

Before starting a pragma-stylistic analysis of the discourse, let us clarify some of its conceptual and terminological aspects. In the pragmatic part of the analysis we will approach both discourses as written speeches. Hence such terms as speaker, hearer, illocutionary act, and illocutionary force are used in the paper interchangeably with the terms arguer or author of the discourse, reader, sentence. This approach, based on the framework of Searle and Vanderveken’s illocutionary logic, will allow us to achieve our major goal – to identify the authors’ communicative intentions. As has already been stated, the author’s communicative strategy is not restricted to rational appeal. He also tries to influence the readers through appealing to their emotions. The first sentence is of great interest for a pragmatic analysis for several reasons. First, the speaker performs a complex illocutionary act consisting of two elementary ones: an illocutionary act of informing:

Strictly as a health issue and warning:

(b) if more HIV-positive immigrants come into the country, more Americans will get the virus and die.

Second, the same pragmatic composition is repeated in the first sentence of the second paragraph. Third, as we have already mentioned the propositional content of the first sentence not only is the most important argument, but also carries the strongest emotional appeal in the discourse.

(a) is defined here as an illocutionary act of informing, because the speaker’s main intention is to let the reader understand the way he will approach the subject in this and subsequent sentences. It also permits him to deflect accusations that he is anti-gay, anti-foreign, anti-HIV-infected people.

(b) is a warning for the American readers about extremely unfavorable consequences awaiting them if the ban is lifted. An important question concerning the claim considered above is does the arguer legitimately use appeal to fear or is it an example of an ad baculum fallacy? We believe the answer is that arguer legitimately uses appeal to fear for the following reason. The arguer does not simply exploit the sense of self-preservation in the audience, he provides valid argumentation to support his proposition throughout the whole discourse. Following Walton (Walton 1992: 165), we consider this argument a valid argument from negative consequences.

The arguer keeps on tailoring his argumentation as explicit or implicit argumentation from consequences throughout the most part of the discourse. This proposition also contains an appeal to fear:

(c) With an influx of infected immigrants the virus could easily start moving in the heterosexual community, as it has in some other countries.

The speaker uses in this sentence the subjunctive mood that together with other characteristics of the illocutionary force indicates that we deal with conjecturing here. The speaker takes a lesser commitment to defend the proposition allowing room for an “emergency escape” by saying I am not warning you about or predicting anything, I am just offering a conjecture.

It must be noted that the pragmatic analysis of the sentence poses a question as to why the speaker abruptly decreases the illocutionary strength of his illocutionary acts thus bringing down the strength of the whole discourse as an illocutionary act complex. Compared to the previous illocutionary act of warning, that has one the strongest illocutionary forces, the arguer suddenly chooses to produce an illocutionary act that has one the weakest illocutionary forces. The lower degree of the illocutionary point of (c) may, of course, be explained by the author’s intention to express a lower degree of certainty he has about the probability that the influx of HIV-infected immigrants will occur to show his confidence in the wisdom of the American public who will not allow this to happen. However, the readers may just as well understand the illocutionary act as an indication that the author lacks evidence to predict this course of events. It is this ambiguity that makes this proposition, pragmatically, one of the weaker arguments in the discourse.

The second means the speaker uses to balance the weaker illocutionary force of the conjecture is the complex illocutionary act of stating HIV is not only contagious, we do not have a cure for it. We argue that in the class of assertive illocutionary forces we need to clearly distinguish an illocutionary force of stating, because to do so is important for the study of argumentation. Searle and Vanderveken (Searle & Vanderveken 1985: 183) believe that state, assert and claim name the same illocutionary force. The study of the role the illocutionary acts play in argumentation shows, however, that there are major differences between the illocutionary force of stating a fact, on the one hand, and the illocutionary force of claiming/asserting that something is a fact, on the other. In the case of stating a proposition, this proposition is presented as a fact that does not require additional argumentation to support the proposition, while in the case of asserting/claiming the same proposition is presented as an opinion of the speaker that it is a fact, which does require additional support for the proposition. As we will show in the following chart, stating has an illocutionary force distinctly different from that of asserting/claiming.

5. Comparative chart of illocutionary forces of asserting/claiming and stating

Asserting/ClaimingStatingMode of achievement of illocutionary pointRepresenting a state of affairs in the form of the speaker’s opinion that the state of affairs is a fact, which requires further proof of the truth of the propositionRepresenting a state of affairs in the form of a fact, which does not require further proof of the truth of the propositionPreparatory conditions

1. The speaker has evidence for the truth of the proposition;

2. It is not obvious to both the speaker and the hearer that the hearer knows the proposition;

3. The speaker anticipates that hearer will not agree with him about the truth of the proposition;

4. The speaker believes that he must defend the truth of the proposition

1. The speaker has evidence for the truth of the proposition;

2. It is not obvious to both the speaker and the hearer that the hearer knows the proposition;

3. The speaker anticipates that the hearer will agree with him about the truth of the proposition;

4. The speaker does not believe he must defend the truth of the proposition Degree of strength of the illocutionary pointThe degree of strength of illocutionary point is considered the medium one for assertive illocutionary forces because the speaker commits himself to defend the truth of the propositionThe degree of strength of illocutionary point is lower than the medium one for assertive illocutionary forces because the speaker does not commit himself to defend the truth of the propositionPropositional content conditionsAny propositionProposition identified as

1. documented data;

2. axiom;

3. well-known fact

4. generally accepted beliefSincerity conditionsThe speaker believes in the truth of the proposition The speaker believes in the truth of the propositionDegree of strength of the sincerity conditionsThe degree of strength of the sincerity conditions is considered the medium one for assertive illocutionary forcesThe degree of strength of the sincerity conditions is higher than the medium one for assertive illocutionary forces because speaker so strongly believes in the truth of the proposition that he does not believe he must defend it

Let us clarify the relation between what we find in the chart and argumentation.

As our analysis shows, the same argument can be presented by the speaker in various forms: in the form of predicting, conjecturing, asserting, claiming, warning, stating, etc. Probably in most cases arguments are presented either in the form of claiming/asserting that something is a fact or stating a fact. If the speaker presents a proposition by stating it, he presupposes that the hearer will not have objections to accept the fact as a fact. This is why, if the audience has reasonable doubts to believe that the proposition is a fact and demands further arguments to defend the truth of the proposition, the illocutionary act of stating must be considered unsuccessful, since as such the audience has not accepted it. For the audience it is an act of claiming/asserting that the proposition is a fact. To avoid such an outcome, the speaker can present the proposition as his personal opinion from the start, performing an illocutionary act of claiming/asserting. However, in this case the speaker must unconditionally commit himself to provide supporting arguments, anticipating doubt.

The distinction between these illocutionary forces is an important one in argumentation because very often an arguer presents his arguments as facts whose truth does not need further defense. By doing that the arguer commits a fallacy of evading the burden of proof (van Eemeren & Grootendorst 1992: 117). In terms of pragmatics, we may define the fallacy as intentional evasion because the speaker evades the responsibility to express the right communicative intention – the intention the illocutionary act with the kind of proposition should possess.

A good example of the fallacy would be the claim contained in the concluding paragraph of the discourse:

(d) Lifting the ban on HIV-infected immigrants is a promise that Bill Clinton made to garner votes from gay rights groups (1.1)

The proposition is presented as a statement of an indisputable fact, but the reader is very unlikely to accept the proposition as a fact.

The reader will most probably perceive the illocutionary act as a claim because the proposition does not belong to any of the four categories of propositions of stating. Consequently, the reader will demand of the speaker the fulfillment of the commitment to provide argumentative support for the proposition. This example is especially striking since (d) is put forward in the last paragraph of the discourse as one of the conclusions to the discourse argumentation.

As we see in Figure 1, the arguer evades fulfilling the commitment to prove the proposition. This makes the proposition more vulnerable to refutation and thus the perlocutionary effect of the illocutionary act and of the whole discourse -persuading the audience – is in jeopardy.

Many HIV-positive people coming into the country would burden the health care system, either with the cost of their own treatment or by spreading the disease to other people, who will wind up in public hospitals is a complex illocutionary act of conjecture. The illocutionary force indicating devices present in the sentence, namely the subjunctive mood, point to this conclusion. Again the speaker seems to avoid using a stronger illocutionary act maybe suggesting that he believes the described course of events will not occur due to the wisdom of the people, who will make the right decision on the matter.

The arguer does not always express his ideas as assertive acts. In some instances he performs directive illocutionary acts. There is a series of three directives in the second paragraph:

Of course, we shouldn’t paint with a real broad brush (suggesting)

We want to be compassionate (requesting)

(g) But we do not want to allow in people with expensive medical conditions and have the taxpayers picking up the tab (urging)

The intention of the speaker is to request that the American people be compassionate but urge them not to allow in people with expensive medical conditions, and have the taxpayers pay for their treatment.

The degree of strength of illocutionary point increases toward (g), because urging expresses a stronger desire of the speaker to get the hearer to do the described action.

6. Logico-semantic analysis of the second discourse

Like in Fig. 1, we see in Fig. 2 a well-organized argumentation. Grounds and their claims almost always follow each other in the text. If we compare the argumentative structure with the actual text we shall see that the

whole argumentation can be broken down to three blocs. The concluding paragraph contains the main explicitly stated claim of the discourse (1.1). The first and the second paragraphs contain arguments in the left part of the scheme; and the third paragraph contains arguments in the right part of the scheme. The second discourse has basically the same argumentative structure as that of the first discourse. It begins with one of the discourse strongest claims and ends with conclusions. The main explicit claim the author makes in the discourse is This prohibition is really a mask for a hatred of foreigners a hatred of people of color, and a hatred of people who have HIV. We believe making this claim the arguer commits a non sequitur fallacy. The arguer has neither mentioned anywhere else in the discourse the hatred of those people nor ever talked about the Americans mistreating foreigners or people of different racial background.

We have identified the fallacy, but we have not identified the motives of the arguer to commit this fallacy. The non sequitur fallacy is a fallacy of reasoning, but does the nature of the fallacy concern only the reasoning process? Does the reasoning process explain to us why the author chose to make this fallacious argument? We believe the nature of the fallacy lies beyond only reasoning process – it is to be searched for in the speaker’s communicative strategy. Having declared that, let us now turn to pragma-stylistic analysis of the discourse.

7. Pragma-stylistic analysis of the second discourse

The author of the second discourse also seeks to combine rational, emotional and aesthetic appeals in her message. But instead of arousing fear or self-pity in the reader, which was done in the first discourse, the arguer tries to arouse pity for HIV-infected immigrants. Just as in the first discourse, already in the first illocutionary act of claiming (which serves best the purposes of an effective persuasive message as a strong opening point) the reader experiences a maximum impact of the combined rational and emotional appeal, the reader’s feeling of pity being the primary target. The arguer continues to seek the goal to appeal strongly to peoples’ pity through appeal to social justice throughout the discourse. The question, therefore, one faces analyzing this discourse is whether the arguer commits any ad misericordiam fallacies in her discourse. We believe the answer is yes and we shall further provide arguments for the assertion.

The second and third sentence form an illocutionary act complex of informing. Once the reader is informed about the situation, the speaker performs a strong direct illocutionary act of claiming

(h) It’s crazy

Moreover, (h) contains an even stronger indirect illocutionary act with a different illocutionary point. It is an expressive act of protesting. The illocutionary point of expressives consists in expressing the speaker’s attitude to a state of affairs (Vanderveken 1990: 105). The main intention of the speaker is to show to the reader that she strongly disapproves of the opponents’ views. As is shown in Fig. 2, the propositional content of the sentence becomes an essential part of several valid arguments. This statement, therefore, makes an important contribution both to the discourse rational and emotional appeals. (h) is the arguer’s major successful step in pursuing the communicative strategy to combine rational, emotional and aesthetic appeals.

Let us now turn to two illocutionary acts performed in the second paragraph that are of importance for our study. As indicated in Fig. 2, the speaker does not provide any argumentative support for propositions:

(i) The law already requires that immigrants show they are not going to become a public charge

(j) In fact, people with HIV can lead long, productive lives in which they can be taxpayers and contribute to this society

Therefore, the reader will certainly understand that the speaker considers the propositions to be statements of facts. The reader will understand the speaker’s communicative intention. So the illocutionary acts will achieve their illocutionary point as illocutionary acts of stating but will the reader accept the illocutionary acts as such? Will the illocutionary acts have their perlocutionary effect?

The propositional content of (i) contains an unclear proposition. The recipient of the message is unlikely to accept the illocutionary act as a statement of a fact because its proposition can hardly be considered a well-known fact or a generally accepted belief. So the answer to the question whether this illocutionary act will have its perlocutionary effect of persuasion should probably be no. As a result, the whole discourse as an illocutionary act complex will have a lesser chance to achieve its perlocutionary effect. In (j) the speaker uses an illocutionary force-indicating device of stating – the parenthetic phrase In fact. The speaker uses this phrase to let the reader know that she does not even anticipate any doubt as to the truth of the proposition. The casual In fact creates an impression that the proposition is added to the previous one almost in passing, just because it is important to mention but one does not need to discuss it. The reader will understand that the speaker wants him to believe the proposition is a fact, but, again, will the illocutionary act have its perlocutionary effect of persuasion of the reader that the proposition is a fact? The answer has to be yes because the reader will most probably accept the illocutionary act as stating a generally accepted belief.

The third paragraph contains one of the strongest ad misericordiam appeals of the discourse. The speaker performs three illocutionary acts with an illocutionary force of accusing If they are found to be HIV-positive during legalization procedures, they are deported- despite the fact that they may well have been infected here; And we don’t tell them how to avoid infecting others once they go home; and We don’t even necessarily tell them that they have the virus. Accusing is a very strong illocutionary act and the speaker must anticipate stronger objections at least from the accused. Therefore it is imperative that the speaker prove the truth of her accusations. Unfortunately, the arguer does not meet her responsibility, because the accusations remain unsupported.

The high level of emotional appeal is reinforced with an aesthetic appeal. By repeating the structure we don’t tell them author makes use of repetition, an effective stylistic device often used by media arguers to emphasize a point or to clarify a complex argument (Stonecipher 1979: 118). The introduction of the amplifying word even to the structure in the last sentence of the paragraph also contributes to the aesthetic and emotional appeals.

The speaker continues to increase her emotional and aesthetic appeals in the last paragraph of the discourse. The sentence This prohibition is really a mask for a hatred of foreigners a hatred of people of color, and a hatred of people who have HIV is marked with the use of the same stylistic device repetition, aimed to make the conclusion aesthetically appealing to the reader. Emotional appeal to pity is evident in the choice of the word hatred being repeated. The illocutionary force characteristics the sentence meets allows us to say that an illocutionary act of condemning is performed. The speaker strives to condemn the ban as inhumane and cruel. Since the degree of strength of the illocutionary point of condemning is even higher than that of accusing the speaker has to take even more commitment to prove her point, than when accusing. As the logico-semantic analysis of the discourse has shown, the author of the discourse does not fulfill the preparatory condition of condemning, the commitment is not met. That is why we can conclude that the emotional and aesthetic appeals are misused as they supplant reason. We believe that the arguer commits an ad misericordiam fallacy here because by accusing the ban advocates of this cruelty and injustice toward the immigrants and condemning them of hatred of all sorts of people without adequate argumentation supporting the condemnations the arguer asks the reader to accept C2 because the immigrants deserve pity.

8. Conclusions

Concerning the first purpose of the paper, let us advance the following conclusions. We have analyzed two American print media argumentative discourses whose authors are engaged in the American print media discussion conducted in the format of a deferred persuasion dialogue. Both parties pursue a rhetorical goal of winning the argument and persuading the reading audience that their position is the right one. The discourses are characterized by two different communicative strategies of persuasion. The author of the first discourse chooses to rely primarily on rational appeal in his message, reinforcing it with an emotional appeal. The first discourse has an illocutionary force of arguing, because in achieving the perlocutionary effect of persuasion the speaker expresses his intention to argue the issues at hand producing logically coherent argumentation. The fact that the claims containing ad baculum appeal have valid arguments supporting them allows us to conclude that the arguer does not use the appeal fallaciously. The author of the second discourse, on the contrary, seems to rely primarily on emotional appeal in her message, sacrificing appeal to people’s reason. The arguer focuses on the wrong and inhumane character of the ban, seeking to arouse in the reader a feeling of pity for the victims of the ban but fails to methodically and carefully argue her points thus committing an ad misericordiam fallacy. The arguer reinforces her emotional appeal with aesthetic appeal. By using various stylistic devices she creates an attractive image of the message. The second discourse has an illocutionary force of condemning. Condemning is a more powerful illocutionary act than arguing because it presupposes that the arguer does not merely argue against something because it is not in the best interests of the hearers, but that he argues against something because it is morally or ethically bad or wrong. If successful, condemning should be more persuasively effective than arguing because it appeals to what Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca call the universal audience (Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca 1971: 30) because the proposition of condemning seeks to appeal to people’s universal sense of right and wrong. However, the stronger the illocutionary act is the more commitment the speaker has to take to achieve the illocutionary point of the act. The second arguer fails to fulfill her illocutionary responsibility. Consequently, we believe the second discourse as a speech act complex is less likely to achieve its perlocutionary effect of persuasion than the first one.

Concerning the second purpose of the paper we may advance this conclusion. Illocutionary logic can be used as a tool that allows us to show which illocutionary acts are best suited for appealing to people’s emotions. Our analysis indicates that, pragmatically, emotional appeals to fear and pity are created by illocutionary acts with high degrees of strength of the illocutionary point, e.g. by warning, accusing, condemning, protesting, and urging.

Concerning the third purpose of the paper it must be noted that it is necessary to distinguish the illocutionary force of asserting/claiming on the one hand from that of stating on the other. The distinction between these illocutionary forces is an important one in argumentation because very often an arguer presents his arguments as facts whose truth does not need further defense. By doing that the arguer commits a fallacy of evading the burden of proof or, pragmatically, a fallacy of intentional evasion, because he evades the responsibility to express the intention to defend the truth of the proposition.

REFERENCES

Eemeren, F. H. van & Grootendorst R. (1992). Argumentation, Communication, and Fallacies. A Pragma-Dialectical Perspective. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hamblin, C. L. (1970). Fallacies. London: Methuen & Co Ltd. Perelman Ch. & Olbrechts-Tyteca L. (1971). The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation. Paris: Notre Dame.

Rybacki, K. C. & Rybacki, D. J. (1995). Advocacy and Opposition: An Introduction to Argumentation. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Searle, J. R. & Vanderveken, D. (1985). Foundations of Illocutionary Logic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stonecipher, H.W. (1979). Editorial and Persuasive Writing: Opinion Functions of the News Media. New York: Hastings House.

Vanderveken, D. (1990). Meaning of Speech Acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Walton D.N. (1992). The Place of Emotion in Argument. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply