ISSA Proceedings 1998 – The Perceived And Actual Persuasiveness Of Different Types Of Inductive Arguments

No comments yet 1. Introduction

1. Introduction

Policy decisions can give rise to lively public debates. Should we build a new airport, expand the old one, or try to cut down on travelling by airplanes? Should we build more motorways or make the public transport cheaper in order to solve the traffic congestion problem? When a debate arises, each option will have its own proponents. They will try to persuade others that their option is indeed in everyone’s best interests. To achieve that goal, they put forward pragmatic argumentation. That is, they claim that their option will probably or certainly result in desirable consequences. The strength of their argument depends on two aspects: The consequence’s desirability and the consequence’s probability. A strong argument in favor of the option would be that the option will certainly result in desirable consequences.

Previous research has shown that people have more trouble evaluating arguments supporting a probablity claim than evaluating arguments supporting a desirability claim (Areni & Lutz 1988). In other words: The argument quality of a desirability argument is more transparent than that of a probability argument. O’Keefe (1995) suggested that argumentation theory provides a framework to study the concept of argument quality. However, he also warned that what should be convincing from the point of view of an argumentation theorist, is not always convincing from a layperson’s point of view.

In this paper, I will first discuss the different types of argument that can be used to support a probability claim. Next, I will review empirical research in which the actual persuasiveness of these types of argument is studied. However, in none of the studies, the persuasiveness of the different argument types has been compared directly. Section 4 contains the description of an experiment in which the same claim is supported by different types of argument. The actual persuasiveness of these argument types is measured, as well as the extent to which the participants think that they are convincing.

2. Types of argument

In policy debates, probability claims typically refer to future events, for instance: building a new airport will boost the economy. To support such claims, one can use inductive reasoning. Usually, three types of argument are distinguished in inductive reasoning (see, e.g., Govier 1992). Following the terminology employed by Rieke and Sillars (1984), these three types are the argument by analogy, the argument by generalization, and the argument by cause.

Rieke and Sillars (1984: 76-77) define an argument by analogy as follows: “(…) you compare two situations which you believe to have the same essential characteristics, and reason that a specific characteric which exists in one situation can be reasoned to exist in the analogous situation”. For instance, to support a claim about the beneficial economic effect of building a second airport, proponents may give the example of another country in which the building of a second airport had a strong beneficial effect on that country’s economy. Essential for the quality of this argument, is the extent to which the two countries are similar. The more similar the countries, the more valid the argument by analogy.

The argument by generalization proposes that “you look at a series of instances and from them claim a general principle” (Rieke & Sillars 1984: 72). For instance, instead of giving just one example of a country profiting from building a second airport, one provides a number of such examples. As the number of examples grows larger, the argument by generalization may result in a argument using statistical evidence. Instead of discussing several examples, one presents a percentage or some other descriptive statistic representing the proportion of countries profiting from building a second airport. The quality of this type of argument depends on the number of observations and the representativeness of the observations. For instance, an argument by generalization based on one hundred examples is normatively better than an argument based on two examples.

However, when (most of) the hundred instances are very dissimilar from the issue at hand, the argument should not be convincing. For instance, the effects of building a second airport in developing countries may not be comparable to building a second airport in The Netherlands.

The argument by cause provides an explanation why a certain effect may arise (Rieke & Sillars 1984: 74). In the case of a second airport, one might argue that building it will improve a country’s economic position because (1) building and running such an airport will provide employment for thousands of people, and (2) it will improve the country’s position as a major distribution point in the world’s economy thereby attracting foreign companies to settle there. The quality of this argument depends on the presence or absence of other factors that might cause the second airport to become a failure or a success.

From a normative point of view, an argument by generalization that is based on a sufficiently large sample of representative instances, should be more convincing than an argument by analogy, especially if the latter uses an example that differs strongly from the issue at hand. Whether an argument by cause should be more convincing than an argument by generalization depends on the extent to which the argument by cause identifies the most important possible causes. The question that will be addressed in the next section is the extent to which what should be convincing, is convincing in actuality.

3. Empirical studies on the persuasiveness of different types of argument

A number of experiments have been conducted to assess whether some types of arguments are more convincing than others. Especially the distinction between the argument by analogy and the argument by generalization has received much attention by researchers. In several reviews, it is concluded that the argument by analogy is more persuasive than the argument by generalizability (see, e.g., O’Keefe 1990: 168-169; Taylor & Thompson 1982: 163-164). Baesler and Burgoon (1994) found 19 experiments in which the persuasiveness of the argument by analogy was directly compared to that of the argument by generalizability. In 13 experiments, the argument by analogy proved to be more convincing than the argument by generalizability; in only 2 experiments, the opposite effect was obtained (No differences between types of argument were found in the remaining 4 experiments).

Based upon such reviews, O’Keefe (1995: 15) noted that there is a distinction between what constitutes a strong argument from normative point of view (i.e., the argument by generalization), and from a descriptive point of view (i.e., the argument by analogy). However, Baesler and Burgoon (1994) claim that the manipulation of the two types of argument is (often) confounded with a second factor: the argument’s vividness. That is, an argument by analogy usually presents an anecdote to support the claim; in an argument by generalizability, the claim is usually supported by statistics. In general, an anecdote is easier to imagine than statistics. Nisbett and Ross (1980) dub this the vividness effect. A vivid argument would be more convincing than a more pallid one. Following this line of reasoning, an argument by analogy would be more convincing than an argument by generalizability, not because it is based on a single instance, but because of its higher imagineability.

To test this explanation, Baesler and Burgoon (1994) manipulated not only the type of argument (argument by analogy or argument by generalizability), but the vividness of these arguments as well. That is, they provided vivid statistical and anecdotial evidence as well as pallid statistical and anecdotial evidence. Controlling the evidence’s vividness led to a pattern of results different from the usually reported one: The argument by generalizibility (employing statistical evidence) proved to be more convincing than the argument by analogy (employing anecdotial evidence). Hoeken and Van Wijk (1997) obtained a similar pattern of results using a different message on a different topic. The vividness of the argument by analogy may therefore be the reason for the often reported finding that the normatively stronger, but less vivid argument is less convincing than the normatively weaker, but more vivid argument.

Compared to the argument by analogy and the argument by generalizability, the argument by cause has received far less attention by researchers. Slusher and Anderson (1996) compared the convincingness of an argument by cause to that of an argument by generalizability. They used a message stating that AIDS is not transmitted by casual contact (including nonsexual household contact or contact through mosquitos). Evidence substantiating this claim was either causal or statistical. The argument by cause, for instance, ran that “The Aids virus is not concentrated in saliva, is not present in sweat, and has to be present in high concentration to infect another person. The argument by generalizability stated that in ”a study of more than 100 people in families where there was a person with AIDS without the knowledge of the family and in which normal family interactions (…) took place revealed not a single case of AIDS transmission.”

The results showed that the argument by cause was more successful at changing faulty beliefs about the ways in which AIDS can be transmitted than the argument by generalization. Because it is much more difficult to change an existing belief than to form a new belief, these results suggest that the argument by cause is a powerful argument. The superior effect of the argument by cause may have two reasons. Slusher and Anderson (1996) state that using arguments by cause result in the availability of explanations why AIDS cannot be transmitted by casual contact. As the availability of explanations increases, people are more inclined to accept the claim. In contrast, the argument by generalization does not lead to an increase of available explanations. A second explanation for the superior effect of the argument by cause may be that it enables people to build a model of why and how an effect may or may not occur. The argument by generalizability does not enable one to construe such a model. Having such a model, regardless of how tentative it may be, strengthens the belief that a certain effect will occur (Tversky & Kahneman 1982).

The empirical studies on the convincingness of different types of argument enable the following, tentative conclusions. Although most studies show that the argument by analogy is more convincing than the argument by generalizability, this effect may be the result of an artefact. In an argument by analogy, usually more vivid, anecdotial evidence is employed, whereas the statistical evidence typically employed in an argument by generalizability is more pallid. When the vividness of evidence is controlled, however, the argument by generalizability is more convincing than the argument by analogy. In the only experiment in which the convincingness of an argument by cause is directly compared to an argument by generalizability, the former proved to be more convincing than the latter. A tentative ordering of the different types of argument would be that the argument by cause is more convincing than the argument by generalizability, which in turn is more convincing than the argument by analogy.

4. The experiment

An experiment was conducted to address two topics. First, I tried to replicate earlier findings that an argument by analogy is less persuasive than an argument by generalizability, which in turn is less persuasive than an argument by cause. Replicating such effects employing arguments on different topics is an important precondition before general conclusions about message and argumentation effects can be drawn (cf. O’Keefe 1990: 121-129). Apart from replication, the experiment extends previous empirical studies. For the first time, the three different types of argument were compared directly. That is, the same claim was supported either by an argument by analogy, an argument by generalizability, or an argument by cause.

The second topic concerns the relation between the perception of the argument’s quality and its actual persuasiveness. In the experiments discussed above, the extent to which participants accepted the claim was measured. They were not asked whether they regarded the argument as strong. In this experiment, participants not only rated the extent to which they accepted the claim, they also indicated their opinion about the argument’s strength. One would expect these scores to correlate. That is, the type of argument being rated as strongest, should be the most convincing one as well. In an experiment by Collins, Taylor, Wood and Thompson (1988), however, participants rated one message as more persuasive than another, whereas in actuality they were equally persuasive. To assess whether the perception of argument strength corresponds with the actual persuasiveness, both variables were measured.

The discussion above leads to the following two research questions:

1. Do different types of argument lead to differences in actual persuasiveness?

2. Do differences in persuasiveness correspond to differences in perceived argument quality?

To answer these questions, an experiment was conducted in which a claim about the future financial success of a cultural centre was backed up by either an argument by analogy, an argument by generalizability, or an argument by cause. The argument by analogy was deliberately weakened through choosing an example that differed on essential characteristics from the issue under consideration.

4.1 Method

Material

The material consisted of three versions of a (fictitious) newspaper article on a council meeting in the Dutch town of Doetinchem. The meeting was about the mayor’s proposal to build a multi-functional cultural centre. It was reported that some of the council members doubted that such a centre would be profitable. They feared that the citizens would have to pay for the losses. The mayor argued that the centre would attract sufficient visitors and make a profit within four years. The argument to support this claim could be either an argument by analogy, an argument by generalization, or an argument by cause. All arguments consisted of 6 sentences and 75 words.

The argument by analogy stated that a similar centre in the city of Groningen had been very successful. It had made a profit within four years. Groningen differed from Doetinchem on several important dimensions. Unlike Doetinchem, Groningen has a university and is much larger than Doetinchem. Furthermore, it is situated in a different part of The Netherlands. In a previous experiment, size of population, type of city, and location in the country, were identified as the most defining characteristics of a town (Hoeken & Van Wijk 1997).

The argument by generalization referred to a study by the Dutch Organization of Municipalities. In the study, the profitability of 27 cultural centres in different towns of varying size, dispersed over The Netherlands had been assessed. On average, the centres had made a profit within four years. Finally, the argument by cause provided three reasons why the cultural centre would be profitable. First, many citizens from nearby towns went to a faraway cultural centre to see movies and plays. Second, a popular movie theatre in a nearby town had burnt down. It was believed that the visitors would find their way to cultural centre in Doetinchem. Finally, Doetinchem’s demographics showed that the number of well-educated people who are well-off increased. Such people like to visit cultural centres.

Participants

A total of 324 participants took part in the experiment. There were slightly more men (51.2%) than women (48.8%). Their age ranged from 17 to 72 with an average of 29 years. Education ranged from primary education to a master’s degree. The majority (67.7%) had completed at least grammar school.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire contained questions on a number of variables such as the participants’ cognitive responses, their evaluation of the article, their own behavior with respect to cultural activities, and some general questions about their level of education, sexe, and age. In addition, to test whether the argument by analogy was perceived as more vivid than the other types of argument, the text’s vividness was measured. The most relevant variables with respect to the research questions were those operationalizing the argument’s actual and its perceived persuasiveness. The argument’s actual persuasiveness was operationalized as the extent to which participants accepted the claim that the centre would make a profit within four years. The argument’s perceived persuasiveness was operationalized by having participants rate the argument’s strength and its relevance.

The acceptance of the claim

The acceptance of the claim that the centre is capable of generating money was measured by the clause “The probability that the cultural centre will make a profit within four years, seems to me” followed by four seven-point semantic differentials. Two of the four semantic differentials had the positive antonym at the left pole of the scale (large, present), the other two had the positive antonym at the right pole (probable, realistic). The reliability of the scale was good (Cronbach’s alpha = .89).

Perception of argument quality

The perceived argument quality was measured using four seven-point semantic differentials and one seven-point Likert scale. The semantic differentials were preceded by the clause “I regard the argumentation supporting the claim that the centre will attract sufficient visitors as”. Two of the four semantic differentials had the positive antonym at the left pole of the scale (sound, relevant), the other two had the positive antonym at the right pole (strong, convincing). For the Likert-item, the argument was repeated. For instance, in the case of the analogy-argument: The mayor referred during the council meeting to the profit made by a cultural centre in Groningen. How relevant do you rate this example with respect to the decision to build a cultural centre in Doetinchem? The participants indicated their response on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from “very irrelevant” to “very relevant”. The five items formed a reliable scale (Cronbach’s alpha = .83).

Design

A factorial design was used, that is, each subject read only one of the text versions. This resulted in three experimental groups. After reading the text, they responded to the various items of the questionnaire.

Procedure

Each participant was run individually. Participants were told that the Linguistics department of Tilburg University was interested in the way in which people made up their mind in case of a referendum. After this introduction, the participant received the experimental booklet. After completing the experimental booklet, participants were informed about the true purpose of the experiment and thanked for their cooperation. An experimental session lasted about 14 minutes.

4.2 Results

First, it was tested whether the different types of argument were rated as equally vivid. In previous experiments, the argument by analogy was often more vivid than the argument by generalizability thereby influencing the argument’s persuasiveness. An analysis of variance revealed no differences between the three types of argument with respect to perceived vividness (F 1).

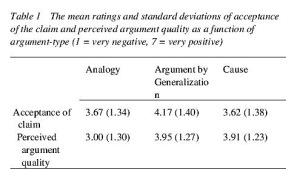

The first research question was: Do different types of argument lead to differences in actual persuasiveness? Table 1 contains the mean ratings of the acceptance of the claim that the cultural centre will make a profit within four years and the mean ratings of the perceived argument quality.

TABLE 1 – The mean ratings and standard deviations of acceptance of the claim and perceived argument quality as a function of argument-type (1 = very negative, 7 = very positive)

An analysis of variance revealed a main effect of Argument type on the acceptance of the claim that the centre would be profitable (F (2, 321) = 5.31, p .01; eta2 = .03). Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey’s HSD test showed that the argument by generalization led to higher scores than the argument by analogy and the argument by cause. The latter two did not differ from each other. The second research question was: Do differences in persuasiveness correspond to differences in perceived argument quality?

Analyses of variance revealed main effects of Argument type for the perceived argument quality (F (2, 320) = 19.61, p .001; eta2 = .11). Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey’s HSD test showed that the argument by analogy was perceived as weaker than the argument by generalization and the argument by cause. The latter two did not differ from each other on perceived strength.

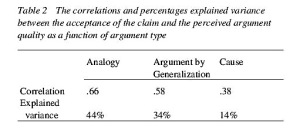

There appears to be a discrepancy between the argument by cause’s perceived persuasiveness and its actual persuasiveness: Whereas the argument by cause is perceived to be stronger than the argument by analogy, it led to similar scores with respect to the acceptance of the claim. This discrepancy is corroborated by the correlations between the perceived argument quality and the acceptance of the claim. The correlations and the percentage of explained variance are displayed in Table 2.

TABLE 2 – The correlations and percentages explained variance between the acceptance of the claim and the perceived argument quality as a function of argument type

Whereas the correlations between perceived quality and claim acceptance are high for the argument by analogy and for the argument by generalization, they are much lower for the argument by cause.

4.3 Conclusion

The first research question was: Do different types of argument lead to differences in actual persuasiveness? The answer is affirmative: The types of argument had a different effect on the acceptance of the claim. However, the differences do only partly replicate the pattern of results obtained in other studies. In this study, the argument by generalizability proved to be stronger than the argument by analogy. As such, it replicates the results of Baesler and Burgoon (1994) and Hoeken and Van Wijk (1997). The expected superior effect of the argument by cause did not arise. On the contrary, the argument by cause proved to be equally convincing as the argument by analogy and less convincing than the argument by generalizability. This result deviates from the results reported by Slusher and Anderson (1996), who found the argument by cause to be more convincing than the argument by generalizability.

The second question was: Do differences in persuasiveness correspond to differences in perceived argument quality? Again, the answer is partly affirmative. In correspondence with the actual persuasiveness, the argument by generalizability is rated as stronger than the argument by analogy. Ratings of the argument’s strength are in both cases strongly related to the actual persuasiveness. In contrast, the argument by cause received higher ratings compared to its actual persuasiveness. It was rated as stronger than the argument by analogy despite the fact that both types of argument yielded similar claim acceptance ratings. The correlation between the perceived argument strength and its actual persuasiveness is much lower for the argument by cause compared to the correlations for the other two types of argument. In the next section, an interpretation for these results will be put forward and the implications discussed.

5. General discussion

The first research question related to the persuasiveness of different types of arguments. In reviews of empirical research, it is often concluded that the argument by analogy is more persuasive than the argument by generalizability. However, as shown by Baesler and Burgoon (1994), this pattern may be the result of confounding argument type with vividness of evidence. When the vividness of the anecdotial evidence employed in the argument by analogy is equally vivid as the statistical evidence employed in the argument by generalizability, the latter is more convincing than the former. In the experiment reported above, there was no difference in perceived vividness, and the argument by generalizability was more persuasive than the argument by analogy. Therefore, the results replicate the finding that the argument by generalizability is more convincing than the argument by analogy if the vividness of the arguments is controlled.

The results on the acceptance of the claim did not replicate previous results obtained for the argument by cause. Instead of being more convincing, the argument by cause proved to be less convincing than the argument by generalizability. A possible explanation for this difference may be the confounding of an argument by cause with an argument by authority. Slusher and Anderson (1996) attacked the claim that AIDS can be transmitted through casual contact or mosquitos. They stated that the AIDS virus has to be present in a high concentration. Neither saliva nor sweat contains a sufficiently high concentration to contaminate another person. This explanation was suggested to be the result of scientific research. Scientists are commonly regarded as competent and reliable sources, thereby lending the argument extra credibility.

In the experiment described above, the explanation of why the cultural centre would be a success was given by the mayor. The mayor himself proposed to build such a centre. Therefore, people may question his impartiality in this matter. Furthermore, a mayor is usually not an expert on the factors that contribute to a cultural centre’s success. Therefore, participants in this experiment may have regarded the source of the explanation as less credible than the (scientific) source in the Slusher and Anderson experiment. This difference in source credibility may have been responsible for the different pattern of results. In order to test this explanation, the causal argument why the cultural centre will become a succes should be ascribed to an independent expert. In that case, the causal argument should be more convincing than the argument by generalizability.

The second research question addressed the relation between perceived argument quality and actual persuasiveness. For the argument by analogy and the argument by generalizability, this relation was straightforward. The higher the perceived argument quality, the more convinced people were, and vice versa. For the argument by cause, the relation proved to be more problematic. Although the argument was perceived as strong, it was not very convincing. The correlation between the perceived argument quality and the actual persuasiveness was markedly lower than the correlations for the other two types of argument.

In the experiment, the participants first indicated to what extent they agreed to the claim that the centre would make a profit. After that, they rated the argument’s quality. The results suggest that only when asked to reflect upon the argument’s quality, the participants who had read the argument by cause realized that the argument was pretty sound. Apparently, the argument by cause needed closer inspection in order to be convincing. This should not lead to the conclusion that only when asked to reflect upon the arguments, people distinguish between strong and weak arguments. If that were the case, no effects of argument type would have been obtained. However, the argument by generalizability lead to a stronger acceptance of the argument’s claim than the argument by analogy. That effect was obtained before participants were asked to reflect upon the argument’s quality. Therefore, even when not instructed to reflect upon argument quality, people are sensitive to differences in argument type.

The discrepancy between the perception of argument quality and the actual persuasiveness only arises for the argument by cause. It is possible that people believe that an argument by cause is convincing whereas in actuality they are not persuaded by it. Collins et al. (1988) report a similar pattern of results on the effect of colourful language. They showed that a message containing colourful language was rated as more persuasive without yielding any significant attitude change. Collins et al. conclude that there is a widespread belief that colourful language facilitates persuasion, thereby influencing people’s ratings of a message’s persuasiveness. In actuality, people would not be sensitive to this message variable.

Something similar may be the case for the argument by cause. Our understanding of the world is largely based on laws of cause and effect. An argument based on such a relation may therefore give the impression of being very convincing without having this effect. The results of the experiment underscore two points. First, the results once again stress the importance of replicating the effects of message and argument variables. Seemingly small differences in argument manipulation can lead to large differences in persuasiveness. Second, it is important to distinguish between what is perceived as convincing and what actually is convincing. Opinions about what constitutes a stronger argument do not necessarily guarantee a stronger persuasive effect. Finally, the results do clarify the need of further study of the conditions under which the argument by cause is persuasive.

REFERENCES

Areni, C. S. & R. J. Lutz (1988). The role of argument quality in the elaboration likelihood model. In: M. J. Houston (Ed.), Advances in consumer research (Vol. 15, pp. 197-203). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Baesler, J. E. & J. K. Burgoon (1994). The temporal effects of story and statistical evidence on belief change. Communication Research 21, 582-602.

Collins, R. L., S. E. Taylor, J. V. Wood & S. C. Thompson (1988). The vividness effect: Elusive or illusory? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 24, 1-18.

Govier, T. (1992). A practical study of argument (3rd Ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Hoeken, H. & C. van Wijk (1997). De overtuigingskracht van anekdotische en statistische evidentie [The convincingness of anecdotial and statistical evidence]. Taalbeheersing 19, 338-357.

Nisbett, R. & L. Ross (1980). Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

O’Keefe, D. J. (1990). Persuasion. Theory and research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

O’Keefe, D. J. (1995). Argumentation studies and dual-process models of persuasion. In: F. van Eemeren, R. Grootendorst, J. Blair & C. Willard (Eds.), Proceedings of the third ISSA conference on argumentation, Vol 1: Perspectives and approaches (pp. 3-17). Amsterdam: SIC SAT.

Rieke, R.D. & M. O. Sillars (1984). Argumentation and the decision making process (2nd Ed.). New York: Harpers.

Slusher, M. P. & C. A. Anderson (1996). Using causal persuasive arguments to change beliefs and teach new information: The mediating role of explanation availability and evaluation bias in the acceptance of knowledge. Journal of Educational Psychology 88, 110-122.

Taylor, S. E. & S. C. Thompson (1982). Stalking the elusive “vividness” effect. Psychological Review 89, 155-181.

Tversky, A., & D. Kahneman (1982). Causal schemas in judgments under uncertainty. In: D. Kahneman, P. Slovic & A. Tversky (Eds.), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases (pp. 117-128). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply