ISSA Proceedings 2002 – Constructing The (Imagined) Antagonist In Advertising Argumentation

No comments yet 1. Introduction: the problem of the imagined antagonist

1. Introduction: the problem of the imagined antagonist

O’Keefe’s (1977) well known and well-used classification and definitions of argument1 and argument2 need little introduction: for clarity, we assume that argument1 “is something one person makes” while argument2 ‘oppositional argument’) “is something two or more persons have (or engage in)” (O’Keefe, 1977: 121). Despite this familiarity there are, nevertheless, certain contentious aspects to the division, not least on whether argument1 represents a form of pseudo-dialogue between protagonist and an imagined antagonist – O’Keefe (1977) himself pointed out that the distinction was only ever “a starting-point for analysis” out of which “[v]ery thorny issues immediately arise concerning how one is to delimit” them (p.127). Here we assume that arguments “require dissensus” (Willard, 1989: 53). Given that such differences of opinion logically entail more than one participant, in cases of argument1, pragma-dialectical theory assumes that arguments exist as dialogue. Indeed examples of rhetorical argument – or argument1 – can be shown to proceed in accordance with the four dialectic stages pragma-dialectical theory identifies (van Eemeren and Grootendorst, 1994), with speech acts operating in these various stages directed at resolving difference of opinion (van Eemeren, Grootendorst & Snoeck Henkemans, 2002; Richardson, 2001). Van Eemeren et al (1996) for example, states:

Argument does not exist in a single individual privately drawing a conclusion: It is part of a discourse procedure whereby two or more individuals who have a difference of opinion try to arrive at agreement. Argument presupposes two distinguishable participant roles, that of a ‘protagonist’ and that of a – real or imagined – ‘antagonist’. (p.277)

In order that the argument1 be as persuasive as possible, its rhetorical moves must, at all dialectical stages of the discourse, “be adapted to audience demand in such a way that they comply with the listener’s or the readership’s good sense and preferences” (van Eemeren & Houtlosser, 1999: 485). With cases of argument1 in which the antagonist is imagined it becomes necessary, indeed essential, to develop as accurate a projection of this antagonist as possible in order that the rhetorical moves employed by the protagonist be as persuasive as possible. In short, arguments should be written or spoken “in such a way that optimal comprehensibility and acceptability”, on the part of the antagonist, is ensured (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, 1994: 223).

Yet how (for example) in the case of a mass broadcast televisual address reaching a wide and heterogeneous audience, should the protagonist of an argument1 go about such rhetorical tailoring? In such a case, the audience will necessarily be non-present, (largely) non-interactive and would undoubtedly subscribe to “varying levels of [argumentative] competence and differing interests, beliefs and values” (Govier, 1999: 189), creating real difficulties for the protagonist. Govier argues that the problem with such an audience, from the perspective of the protagonist (though she does not use this term!) is that “one knows so little about it and cannot interact with it at the stage when one needs to do so in order to improve the quality of one’s argument” (1999: 195). Further, Govier argues that any evaluation of the acceptability (in the eyes of the audience) of an argument1 presented to a mass audience, is rendered impossible since “there is no identifiable audience point of view to apply that notion” (1999: 197). For Govier, pragma-dialectic theory is particularly ill-suited for evaluating argument presented to a mass audience because of its assumption that argument1 exists as dialogue. In short:

There is no interaction between parties […] and there is no decent basis for constructing or envisaging an interaction, because the viewpoint of the antagonist is unknown and is not even singular. The antagonist is not only absent and unable to perform any of the actions or concessions required in this model, ‘he’ is multiple and has no determinable point of view. (Govier, 1999: 197)

In this paper, we attempt to address the problems posed by the non-interactive, heterogeneous audience. Using the example of advertising – a genre of communication whose argumentation is comprehensively adjusted to appeal to an identified audience – we argue that it is more fitting to speak of ‘constructed antagonists’, who are not simply argued at (in the conventional sense of argument1) but are, in fact, demarcated via strategies of inclusion and exclusion. We introduce and discuss a proposed ‘taxonomy of inclusion’ through which advertising argumentation must orientate itself in constructing such an antagonist. Throughout, we adopt a perspective we consider to be consonant with pragma-dialectical theory: that advertising, like all argument, is constituted by an interface between structure and rhetorical content and an argumentative theory that embraces the nuances of both is essential to any account of argument. Further, we believe that our proposed taxonomy strengthens the pragma-dialectical model – particularly against the problems of the non-interactive audience – providing a possible account of how the opening stage of argument1 not only identifies the standpoint of protagonist but also constructs that of the antagonist.

2. Advertising Discourse

Myers (1994) argues that advertising is a genre of communication borne of economic surplus. The corresponding need for manufacturers – and perhaps capitalism as a whole – to both create consumers out of citizens and to nurture these consumers’ desire for branded commodities is the driving force behind advertising. Developed at the end of the nineteenth century in an attempt to bring consumption in line with over-production, “adverts construct positions for the audience”, offering “a relationship between the advertiser and the audience based on the association of meaning with commodities” (Myers, 1994: 10). Therefore, the key questions to ask when reconstructing advertising argument – and as such, the central questions upon which our paper is based – are: ‘who is communicating with who?’ And ‘how is this communication managed?’

Previous work on the discourse of advertising has illustrated how selections in form, the mode of address, transitivity, modality, style and lexis, music and a range of other semiotic systems differ according to the consumer that an advertiser is targeting (Cook, 2001; Delin, 2000; Dyer, 1982; Myers, 1994; Thornborrow, 1994; Williamson, 1978). In this paper we add argumentation to this list – indeed we suggest that the linguistic elements of the aforementioned list can, to a greater extent, be replaced by the entry of argumentation, given that a pragma-dialectical analysis of argumentation necessarily entails examination at these levels and others.

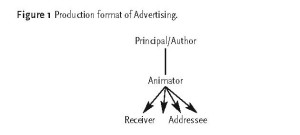

When analysing mediated argumentation we first need to bare in mind that the sender of the message is not always the same as the person who actually speaks it. In a television advert, for example, the protagonist may be an actor, though responsibility for the argument lies with an advertising agency. Goffman (1974; 1981) provides a useful approach to theorising this speaker/writer responsibility in his account of the ‘production format’ of utterances (by which he includes text and talk), developed as part of his theory of ‘footing’, the finer detail of which is surplus to the requirements of the present paper[i]. More important is the recognition that the individual(s) receiving (reading or watching) the advertisement are not always the addressee – or the person for whom it is intended. Rather, the addressees usually are “a specific target group, but the receiver is anyone who sees the ad” (Cook, 2001: 4). Such a distinction can be represented graphically, thus (Figure 1):

This is not to suggest or assume any particular resulting reaction on the part of these addressees of course. Indeed, as Cook (2001) points out, for too long analyses of adverts proceeded in accordance with the “unproven assumption that addressees only have one impoverished way of responding to discourse [and…] that people are tricked into believing that if they buy the product they will experience the attractive lifestyle of the characters” (p.203). We do not offer any such deductive leap regarding the effectiveness of advertising in this regard, specifically the difficulties in demonstrating any alteration in reader/viewer beliefs, attitudes of behaviour (Gunter, Furnham & Frost, 1994; Gunter, Tohala & Furnham, 2001). Rather, this paper focuses upon two issues: First, the potential problems in disaggregating and disambiguating the participants and non-participants in mediated argumentative discourse. Second, since adverts “draw upon and share features with many other genres, including political propaganda, conversation, song, film, [etc.]” (Cook, 2001: 12), and given the strong evidence which suggests that advertising is a parasitic discourse, drawing upon rhetorical strategies of other argumentative, political and semiotic media, this paper (and the claims we will be making) maybe of significance and of use to studies of argumentation in these areas.

2.1 Advertising as an argumentative genre

As Willard (1979) has argued, for too long the study of argument was unfortunately “coloured by the assumption that the claims and the reasons [of argumentation] must be linguistically serialised” (1979: 212). Adopting such a language-dependent position will only ever provide an inadequate account of argumentative discourse genres such as advertising. We consider advertising discourse to be per se argumentative given that advertising offers evidence – often implicit, indirect or semiotic support in addition to (largely non-requisite) premises – in defence of a contested or contestable position.

When first approaching advertising argumentation it is useful to discuss the genre in terms of three inter-related yet still theoretically distinct categories: the advert’s focus; its format and its form. Only in the third of these categories (form) do manifest argumentative features occur; the remaining two categories (focus and format) however, provide both latent argumentative features and the frame within which the manifest argumentation resides. Taking focus first: the focus of the advert relates to whether the advert is aimed at promoting a purchasable product or at promoting ideas and information. There is, of course, a strong argument to suggest that all adverts are structured upon the selling of ideas, with product adverts being designed to sell not just the named brand but also the ideology of consumption itself. The recent work of Smith (2002), for example, has shown that the products advertised in the immediate period of post-Soviet Russia were, more often than not, unavailable for purchase – it was the idea of mass, individualised consumption that these adverts were selling rather than the named and unavailable products.

Second, the format of the advert is crucial to the reception and success of its argument and the following key features (from Cook, 2001) should be accounted for in analysis:

Medium – broadcast (televisual and/or audible) – print (newspaper, magazine, billboard, etc.)

Slow drip campaign (customary or ‘everyday’ products) vs. the sudden burst (seasonal, topical or fashionable products)

Short copy vs. long copy advertising

Finally the features of an advert’s form have unequivocal and direct effect on the content of its arguments. For example:

hard sell vs. soft sell advertising

distinction: the level of directness of the sales pitch; explicit mention of desirability rather than allusion

reason vs. ‘tickle’ advertising

distinction: reason ads give motives for consumption; ‘tickle’ adverts rely on emotion, humour and mood

3. Categorising the addressee

Already from the preceding discussion we can start to see how the implicit and explicit argumentative strategies of adverts are positioned in relation to target audience (or consumer). Here we will begin to examine a proposed structure within which these strategies are placed. We will begin with a relatively formal exegesis before applying this structure to an example.

3.1 Inclusion/ Exclusion

We might think of the strategic moves of an advert in terms of manoeuvres aimed at providing an argumentative slot within which potential antagonists might/will position themselves. This is achieved, in effect, by creating, rhetorically for the most part, a template of the antagonist which the audience or consumer is asked to fill. What is more, this template, or constructed antagonist, is designed so that some particular individual within the audience can quickly identify his/her “fitness” for the template through relatively simple disjunctive devices between some identifying property and its negation. It is from this simple audience filtering that we get to the principle device in our taxonomy: inclusion and exclusion.

This binaried device is fairly straightforward and we are not using inclusion and exclusion in a highly technical way. The point is simply that, through a particular rhetorical device or devices (of the many with which we are familiar in advertising genres) an audience is presented with an argumentative slot or antagonist’s position that divides the audience in terms of A v ~A. Of the disjuncts, A is that part of the audience included by the rhetorically defined argument position, ~A is that part of the audience which is excluded by virtue of its lack of fit with the rhetorically defined argument position. Further, as suggested earlier when discussing “hard vs. soft” advertising, adverts don’t simply “say” who their product, information etc. is aimed at and they don’t “state” that certain groups or people are to be excluded by default. We therefore need to introduce a further taxonomic device that enables us to handle the interplay between who is and is not included and excluded (and also how). This motivates the move to defining inclusion and exclusion as being either implicit or explicit.

3.2 Implicit/Explicit

We can again think of an implicit/explicit dichotomy in terms of a fairly straightforward notion of disjunction. When an antagonist slot is constructed for an audience it is done largely in terms of defining one of the disjuncts A v ~A. As such the defined disjunct, being the primary position in antagonist construction, is explicit, and ~A, in being left undefined (except as an unstated non A default) is implicit.

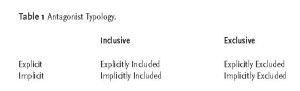

As with the notions of inclusion and exclusion, explicit and implicit are not being used in any peculiarly technical way. We want to take them as meaning: a rhetorical outcome explicitly stated; and a rhetorical outcome implicated by, or inferred from, the explicit statement. Further, “implicit” and “explicit” are intended, within this taxonomy, to act as modifiers on the notions of inclusion and exclusion so that the taxonomy divides the construction of the antagonist slot into four possible types with regard to targeted groups (Table 1):

So, whenever an addressor constructs an antagonist, he does so through the construction of an argument slot that by including and excluding (implicitly or explicitly) certain groups, or types, allows the addressee to test himself for “fit” to the slot.

3.3 The Function of the Types

As we have seen, there are four possible ways, or types, that the addressor can use to construct an antagonist slot. It may serve to say a little more about how this is supposed to work and how the groups are inter-related. We shall do this firstly by saying a little more about each taxonomic type.

Explicitly Included: When an addressor identifies or constructs the antagonist position through explicit inclusion they make explicit rhetorical moves that are aimed at appealing directly to some identified group. This is perhaps the most commonly used constructive strategy and we can identify it, for example, in the chosen time slots of broadcast advertising, or the circulation demographic of some print media adverts, whereby a particular time slot and programming type or particular newspaper, magazine etc. is seen as attached to a particular sub-set of potential audience.

Explicitly Excluded: As we have said, the most common move in constructing an antagonist is to make an explicit attempt to directly address the audience that the advertising is aimed at. However, it is possible for the addressor to do this by making an explicit characterisation of the audience he does not want to sell his product to. Although rarer it is still possible to make an explicit statement or definition of ~A in order to implicitly identify and include A. (Volkswagen and Audi have very recently employed just such a strategy: Audi identifying a particular character who would not buy their product; VW identifying those who do but are undeserving).

Implicitly Excluded: This particular taxonomic category is that part of some audience that is excluded from the antagonist position under construction but is excluded as a consequence of holding some antithetical position to the explicitly identified and targeted (for inclusion) group.

Implicitly Included: This category is that part of some audience that the addressor wants to place within the constructed antagonist position but does so as a consequence of explicitly defining an antithetical group for exclusion.

3.3.1 The Interrelation of types

It should be relatively clear from the way we have identified and defined the categorical types how we think they are related, so if we are explicit about inclusion we are implicit about exclusion and vice versa. As this suggests, there are a couple of features of the way the antagonist position can be defined (and the antithetical accompaniment that comes as corollary) that fall out of this taxonomic definition. So taking A to be the included (and ~A to be excluded):

1. Wherever an antagonist is constructed both A and ~A will form part of the construction (this is a constructive disjunction)

2. Wherever A is stated explicitly ~A is implied (or is implicit)

3. Wherever ~A is stated explicitly, A is implied (or is implicit)

4. Only one constructive disjunction is stated at each stage in the construction of the antagonist

5. The “object” identified by A or ~A cannot be stated both implicitly and explicitly within the same constructive disjunction, that is, A, the included, cannot be stated both explicitly and implicitly at the same stage of construction (similarly for ~A).

6. A disjunct within a constructive disjunction cannot be part of a constructive stage without an appropriate (from (2) (3) and (4)) accompanying disjunct (from (1))

3.4 Unacknowledged Audience

It seems as though on this picture we still need to get a better understanding of ~A. After all, it looks as though we are defining ~A as whatever A is not and there are two ways in which this could done: by thinking of domain of discourse we can think of ~A in terms of either a restricted or an unrestricted domain. Taking a quick example of what we mean by restricted and unrestricted domain we can think of A as, say a twenty-something female. ~A, depending on the domain of discourse, will be: anything that is not a twenty-something female (males, horses, running shoes and so on) if we take the domain of discourse to be unrestricted; or any female that is not a twenty-something if we take the domain of discourse to be restricted to females.

Therefore, how we define our domain of discourse (and so the scope of ~A) will have some bearing on how we think the unacknowledged audience is dealt with (that is, whether there is one, and if there is an unacknowledged or “ignored” audience, how it is isolated and treated for future fit to antagonist slot). If we take the domain of discourse to be unrestricted, for example, you are either included or you are excluded and thus there is no portion of a potential audience that is ignored – if you are excluded, this places you in a group that covers a whole range of potential sub-sets or sub-domains of the “receiver”. On the other hand if the domain is taken to be restricted then it looks as though there are three groups that arise from the inclusive/exclusive strategies; included, excluded, and “ignored” or “unacknowledged”. If we take our domain of discourse to be restricted then it looks as though we owe an explanation above and beyond that which we give for the included and excluded, i.e. an account of the ignored and its relation to the extension of the “receiver” (does it form a tripartite exhaustion of this set with the included and the excluded?) and an explanation of the relation between it and the Principal and Author (do the Principal and Author in advertising really want to ignore some portion of an audience? Is the “ignored” really ignored or are they addressed but held in mind for deferred interaction? etc.) In short, depending on whether we think of the domain of discourse as being restricted or not will determine whether our taxonomy of inclusion and exclusion exhausts the extension of the “receiver”, or whether we produce a further taxonomic group; “the ignored”.

We think that the domain of discourse is restricted in the construction of imagined antagonists and that the included and excluded does not exhaust the receiver. However, we also think that this does not mean that there is some proportion of the “receiver” that is ignored (despite my introduction of this terminology above) throughout the construction of an antagonist slot by the addressor. In explaining how the “ignored” is related to the addressed and the Principal/Author we think we can show that constructing the antagonist does not mean that any part of the receiver is truly ignored, and that ultimately it would not be in the interest of the addressor to do so. How will be made clear below.

3.5 Multi-layered Applications of the Binary

The way in which that part of the “receiver” which appears to be unacknowledged or ignored at some constructive stage can be accounted for (as the adoption of a restricted domain requires) is by noting that the construction of an antagonist slot is multi-layered. That is to say that the “receiver” will be divided at some initial level between A and ~A in very broad terms. A is then further divided by a second application of a constructive disjunction (i.e. submitted to a further constructive stage) between A and ~A.[ii] This re-application of the constructive disjunction at a further stage of construction can continue across many stages until the antagonist slot looks suitably well defined. Indeed, on the level of advertising, it is part and parcel of a successful campaign that it is able to take the constructive stages far enough to identify its target well, without over specifying the antagonist and so restricting its market. So, how does this proposed multi-staged construction of the antagonist provide an account of the “ignored”?

The answer is fairly straightforward. The excluded (or ~A) of some preliminary stage of construction, becomes “ignored” at some further stage. So if we imagine a multi-staged construction of the antagonist slot where the whole of the receiver is addressed (by either inclusion or exclusion) at the first stage, with the included of the first stage addressed further at a second stage, and the excluded of the first stage addressed no more at any stage in the rest of the construction (and so on with the included and the excluded of each constructive stage), we can see that through the accumulation of each stages excluded (except the last) we have a fair body of what looks like “the ignored” come the final constructive stage and the definitive account of A (the constructed antagonist). However, as should now be plain, the whole of the receiver is addressed at some point in the construction and so no one is ultimately ignored.

There is something interesting about this in that it captures a very basic intuition about advertising and marketing; although a targeted group of some advertising campaign might be small, the bodies behind the advertising (companies, governmental agencies etc.) are not likely to want to make any group isolated from the conventions and milieu of advertising; incomeless teenagers, for example, are tomorrow’s car driver, beer drinker etc. The advertiser is in the position of wanting to talk to everyone personally at once.

Another interesting feature of this multi-layered application is that it takes pressure off the constructive binary in its role of constructing the antagonist. Instead of one application of the constructive disjunct defining A and ~A we can take away the strain of giving tight definitions (particularly the included, A) and constructing the antagonist in one fell swoop by allowing the construction to develop more gradually over a multitude of constructive stages using more and more rhetorical devices in the process of defining the included and the excluded at each stage.

One final point here before we go on to make an application of this structure (along with the involved notions of inclusion and exclusion) is that the notion of stages might allow us to tell an interesting tale about the relations between the excluded of each constructive stage. There might be some way to describe the degree of exclusion of each stage as we find it in the final constructive stage. The thought here is that we can follow a similar strategy to that employed by Fairclough (Fairclough: 1995) in his discussion of “how events, situations, relationships, people and so forth are represented in [media] texts” (Fairclough: 1995, 103). Fairclough’s discussion focuses at some points on noting what is absent from the text and, to some extent, “a scale of presence” (Fairclough: 1995, 106). The comparison with Fairclough’s ideas for absence in media text would end here though since he thinks his scale, “running from ‘absent’ to ‘foregrounded’” (Ibid.) covers both what is present and what is absent, whereas we are here talking about the extent of exclusion. The point here is no more in depth than to suggest that the structure of our constructive stages might allow us to give a scaled account of exclusion from the antagonist slot in a way similar to that envisaged by Fairclough for presence in media texts generally. Although the need to provide an account of this scale here is secondary (and so will be passed over) it is good to note that it seems plausible, and perhaps even desirable[iii], that such an account could be given.

4. Extended Example

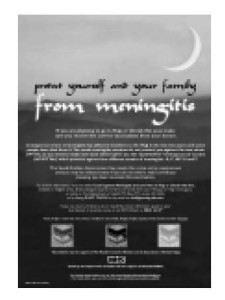

Let us then, make a fairly cursory application of the general structure that we have been discussing to an example. The example we are using is a one-page information advertisement from The Muslim News on 21st December 2001 (See Figure 2). There are multiple uses of the constructive disjunction through out this advertisement and we shall treat them in turn as they form part of the wider, multi-staged antagonist construction. We will look at both the ignored at each stage and the rhetorical devices that seem to be at play. We will finish with a final result which gives us the antagonist that is constructed for this advertisement through these multi-staged applications of the constructive disjunction, however, we will not provide an account of the ignored or excluded at this final stage since it is not clear how we should differentiate these at the point of final definition for A.

We should note that there is also room for some explanation of how the domain of discourse shifts from one constructive stage to the next; just as the excluded from one stage becomes the ignored of the next, the included of one stage becomes the domain of the next. We shall omit this detail here though since we have paid no formal or detailed attention to it.

Figure 2 – Copyright on Figure 2 was unclear at date of submission. Every attempt is being made, both by the authors and relevant personnel at the HMSO, to clarify copyright and grant permission for use before publication.

The construction of the antagonist here then may go something like this:

Stage One:

Domain – People

Ignored – No one

Explicitly Included – Muslims

Implicitly Excluded – Non-Muslims

Rhetorical device: The location of the advertisement in the Muslim News, a medium that has a high percentage Muslim demographic. The paper is aimed at Muslims, this is explicit in the name etc., non-Muslims then are implicitly excluded

Stage Two:

Domain – Muslims

Ignored – Non-Muslims

Explicitly Included – British Muslims

Implicitly Excluded – Non-British Muslims

Rhetorical Device: The use of English language and appeal to authority of the Muslim Council of Britain, Association of British Hujjaj.

Note:

Arguably this definition of British Muslims is apparent at the first stage since the newspaper uses the English language and has a target demographic of British Muslims. This is not a problem for our taxonomy since the advertisement is also capable of standing on its own and has been widely distributed as wall posters for doctor’s surgeries. This is why there are rhetorical devices at play in the poster itself that help to include Muslims and exclude non-Muslims (the first stage’s constructive disjunction); note the semiotic devices at play, iconic and symbolic alike, in the “Arabic” style font and crescent moon aimed explicitly at including Muslims and implicitly at excluding non-Muslims. It is unsurprising then that the inclusive strategies of the first and second stage overlap to some extent here.

Stage Three:

Domain – British Muslims

Ignored – Non-British Muslims

Explicitly Included – “Responsible” British Muslims

Implicitly Excluded – “Dependent” British Muslims

Rhetorical Device: The imperative “protect yourself and your family “. This command isolates those who are either responsible for themselves or for themselves and their families. It implicitly excludes those British Muslims that are dependent upon a parent or a carer since no mention of them is made.

Stage Four:

Domain – “Responsible” British Muslims

Ignored – “Dependent” British Muslims

Explicitly Included – “Responsible” British Muslims with unvaccinated family members

Implicitly Excluded – “Responsible” British Muslims without unvaccinated family members

Rhetorical Device: The completion of the imperative with “from meningitis”. Obviously those British Muslims who are responsible for obtaining vaccines for themselves and their families and have already done so need to be excluded. Here they are excluded implicitly because the imperative makes direct (and so explicit) appeal to those Muslims that are responsible for themselves and families with reference to the vaccine.

Stage Five:

Domain – “Responsible” British Muslims with unvaccinated family members

Ignored – “Responsible” British Muslims without unvaccinated family members

Explicitly Included – “Responsible” British Muslims with unvaccinated family members going to Hajj or Umrah

Implicitly Excluded – “Responsible” British Muslims with unvaccinated family members not going to Hajj or Umrah

Rhetorical Device: The conditional “If you are going to Hajj or Umrah this year, make sure you receive the correct vaccinations from your doctor”. It is easy to use this statement to test ourselves for fit. If I am not going to Hajj or Umrah then I know that the rest of the advertisement is not relevant to me and so I am excluded. If am going to Hajj or Umrah then I know that I must continue to engage further to test for fit (or to adopt the antagonist position).

Note:

There seems to be a possibility that this stage might precede the straight forward imperative at stage four, that is, that the antagonist is better defined first by including those who are going to Hajj or Umrah and then those who are not vaccinated. This is open to debate. However, it seems more likely that these kinds of thought are because of some inclinations we have about the way we expect the strategy to work rather the way it does. It seems that in this case, the way that the poster is read and constructed, the “responsible” are isolated first and the pilgrims second. The order of the constructive stages are separate from the rhetorical effectiveness of an advertisement. We might think that the antagonist would be better defined if the stages were ordered differently, but this is separate to the way in which the antagonist is actually constructed by the addressee.

The position, or antagonist construction, that we find ourselves with in the end is the included of the final stage. In this case then, what we get is this:

Final Result:

Constructed Antagonist — Unvaccinated “responsible” British Muslims going to Hajj or Umrah

Rhetorical Device: This still may not be the final term in this example, since advertisement, having established a slot for a potential antagonist through various rhetorical stages, then goes on to provide more in depth information aimed specifically at this construction. However, the information that follows in the advert is about the specific kind of meningococcal vaccines that are required, where to get them and where to get more information should it be needed. All of this is aimed at the constructed antagonist that we arrive at the end of the various inclusive and exclusive stages.

5. Conclusion

In this paper we have attempted to address the problems which the heterogeneous, non-interactive antagonist poses to argument1. We introduced an approach to the analysis of argument1 which suggests that, in order to construct a comprehensible, acceptable and hence successful argument1, protagonists should (and, in the case of advertising, do) construct the antagonist position through a taxonomy of progressive inclusion. We have shown, through the extended application of our taxonomy, that a pragma-dialectic approach to argumentation can deal with the problems of non-interactive, heterogeneous audience Govier suggests. Our example and motivation throughout has drawn on the genre of advertising which we take, and hope to have shown, is an example of argument (argument1) but with the interesting anomaly of non-interactive and/or heterogeneous audience that Govier sees as problematic. It should also be clear that we think the ‘taxonomy of inclusion’ used in constructing an antagonist in advertising discourse is applicable to wider scenarios of non-interactive and heterogeneous audience. Consequently, we feel that we have shown a development and strengthening of the pragma-dialectical model by providing an account of antagonist construction in argument1.

NOTES

[*] Copyright on Figure 2 was unclear at date of submission. Every attempt is being made, both by the authors and relevant personnel at the HMSO, to clarify copyright and grant permission for use before publication.

[i] Goffman argues that in any communicative event, the speaker/writer role can be dissected into three “functional nodes in a communicative system” (1981: 144) – the animator, the author and the principal. Taking each of these in turn, Goffman suggests: the animator is the “body engaged in acoustic activity”, or the “individual[s] active in the role of utterance production”; the author is realised by “someone who has selected the sentiments that are being expressed and the words in which they are encoded”; whilst the ‘node’ of the principal falls to “someone whose position is established by the words that are spoken, someone whose beliefs have been told, someone who is committed to what the words say” (emphases added, Ibid.).

[ii] This is part and parcel of why we think that we should adopt restricted domain of discourse; if the domain were unrestricted, then ~A at different constructive stages of the same construction would be co-extensional, and this seems not to capture what goes on in the narrowing of an audience or targeted group; this should become clearer in the extended example given below.

[iii] Desirable to the extent that there is a basic intuition that, for example, in an advertisement aimed at black male youth, the white elderly female population seem to be more excluded than, say, white male (or perhaps even female) youth, even though all are arguably excluded.

REFERENCES

Cook, G. (2001) The Discourse of Advertising. London: Routledge

Delin, J. (2000) The Language of Everyday Life. London: Sage

Dyer, G. (1982) Advertising as Communication. London: Methuen.

Eemeren, F. H. van & Houtlosser, P. (1999) Strategic manoeuvring in argumentative discourse, Discourse Studies, 1(4), 479-497.

Eemeren, F. H. van and Grootendorst, R. (eds.) (1994) Studies in Pragma-Dialectics. Amsterdam: Sic Sat

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst, R. & Snoeck Henkemans, A. F. (2002) Argumentation: Analysis, Evaluation, Presentation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eemeren, F. H. van, Grootendorst, R. & Snoeck Henkemans, A. F., Blair, J. A., Johnson, R. H., Krabbe, E. C. W., Plantin, Ch., Walton, D. N., Willard, C. A., Woods, J., Zarefsky, D. (1996) Fundamentals of Argumentation: A Handbook of Historical Backgrounds and Contemporary Developments. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Fairclough, N. (1995) Media Discourse. London: Edward Arnold.

Goffman, E. (1974) Frame Analysis. New York: Harper & Row.

Goffman, E. (1981) Forms of Talk. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Govier, T. (1999) The Philosophy of Argument. Newport News: Vale Press.

Gunter, B., Furnham, A. & Frost, C. (1994) Recall by young people of television advertisements as a function of programme type and audience evaluation, Psychological Reports, 75, 1107-1120.

Gunter, B., Tohala, T. & Furnham, A. (2001) Television Violence and Memory for TV Advertisements, Communications, 26, 109-127.

Myers, G. (1994) Words in Ads. London: Edward Arnold.

O’Keefe, D. J. (1977) Two concepts of argument. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 13, 121-128.

Richardson, J. E. (2001) ‘Now is the time to Now is the time to put an end to all this.’ Argumentative Discourse Theory and Letters to the Editor. Discourse and Society, 12 (2), 143-168.

Smith, K. (2002) Applying a Postcolonial Model to the Evolution of Translation Strategies for Russian Language Advertising Texts. Paper presented at the Annual Postgraduate Conference for the Social Sciences, University of Sheffield, January.

Thornborrow, J. (1994) The Woman, the Man and the Filofax: Gender positions in advertising. In S. Mills (ed.) Gendering the Reader (pp. 128-151). London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Willard, C. A. (1979) Arguing as epistemic II: A constructivist/interactionist view of reasons and reasoning. Journal of the American Forensic Association, 15, 211-219.

Willard, C. A. (1989) A Theory of Argumentation. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Williamson, J. (1978) Decoding Advertisements: Ideology and meaning in advertising. London: Marion Boyars.

You May Also Like

Comments

Leave a Reply